Abstract

Acute leukemias are a group of aggressive malignant diseases associated with a high degree of morbidity and mortality. An important cause of both the latter is infectious complications. Patients with acute leukemia are highly susceptible to infectious diseases due to factors related to the disease itself, factors attributed to treatment, and specific individual risk factors in each patient. Patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia are at particularly high risk, and microbiological agents include viral, bacterial, and fungal agents. The etiology is often unknown in infectious complications, although adequate patient evaluation and sampling have diagnostic, prognostic and treatment-related consequences. Bacterial infections include a wide range of potential microbes, both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species, while fungal infections include both mold and yeast. A recurring problem is increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents, and in particular, this applies to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase resistance (ESBL), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and even carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE). International guidelines for the treatment of sepsis in leukemia patients include the use of broad-spectrum Pseudomonas-acting antibiotics. However, one should implant the knowledge of local microbiological epidemiology and resistance conditions in treatment decisions. In this review, we discuss infectious diseases in acute leukemia with a major focus on febrile neutropenia and sepsis, and we problematize the diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic aspects of infectious complications in this patient group. Meticulously and thorough clinical and radiological examination combined with adequate microbiology samples are cornerstones of the examination. Diagnostic and prognostic evaluation includes patient review according to the multinational association for supportive care in cancer (MASCC) and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scoring system. Antimicrobial treatments for important etiological agents are presented. The main challenge for reducing the spread of resistant microbes is to avoid unnecessary antibiotic treatment, but without giving to narrow treatment to the febrile neutropenic patient that reduce the prognosis.

Keywords: Leukemia, Chemotherapy, Stem cell transplantation, Infectious disease, Sepsis, Bacteremia

Introduction

Acute leukemia is a group of highly malignant blood disorders characterized by clonal growth of immature progenitor cells in the bone marrow. This infiltration leads to severe thrombocytopenia, anemia and leukopenia, and that makes fatal within a few weeks this disease if left untreated. There are three major groups of acute leukemias; acute myeloid leukemia (AML),1 acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL),2 and on very rare occasions mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL).3 The clinical presentation is often similar, although the treatment protocols are different, and the diseases can only be cured by intensive chemotherapy treatment, possibly in combination with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).1–3 Infectious complications continue to be a significant cause of both morbidity and mortality in acute leukemia patients. In the present article we review the current and update knowledge regarding pathophysiology, epidemiology and etiology of infectious complication in patients with acute leukemia. Finally, we discuss optimal approaches to adequate diagnosis and discuss treatment options for this demanding patient group.

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

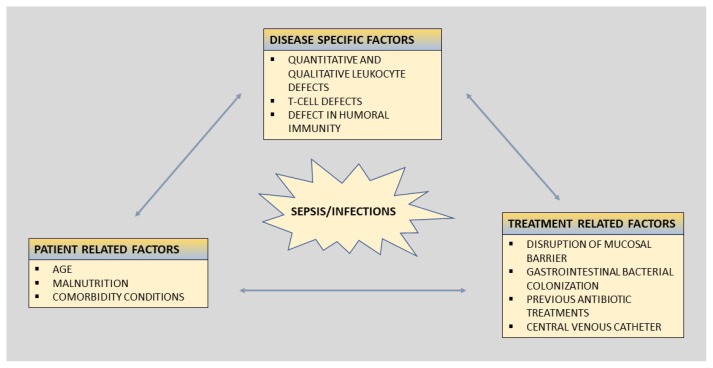

The clinical susceptibility for infections among patients with hematological malignancies is multifactorial. The risk of development and the severity of infections are determinate by a complex interplay between the pathogen and its virulence, and the degree of impaired defense mechanisms of the host. The risk of infection can broadly be divided into (i) disease-associated factors, (ii) patient-related factors, and (iii) treatment-related factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk factors for infections in patients with leukemia.

The figure summarizes risk factors for infection in leukemia patients, which broadly could be divided into disease specific factors, patient related factors, and treatment related factors.

Disease-associated Factors

In acute leukemia, normal bone marrow function is to more or less extent, replaced by abnormal maturation and dysregulated proliferative immature cells, resulting in neutropenia and impaired granulocyte function.1–3 It is well established that quantitative reduction in circulating immune cells makes the organisms more susceptibility for invasive infections.4 Furthermore, immature myeloid cells have the potential to inhibit the antigen-specific T-cell response.5 The humoral immune system is also affected by the disease and its treatment, so the majority of patients will have immunoglobulins’ deficiency. IgG and IgM being the most affected immunoglobulins, and humoral defect immunity can also be present in patients achieving complete remission.6 Finally, the incidence and severity of infections and sepsis are very different in AML patients compared to ALL patients. Induction treatment induces in AML more prolonged neutropenia, which favors infectious complications with early deaths, significantly more frequent in AML patients compared to ALL patients.7–10

Patient-related Factors

Intrinsic properties related to the patient itself are also important in the assessment of infection risk in patients with acute leukemia. Age itself is a major risk for developing infectious complications during the treatment of acute leukemia.11 The natural function of the immune system declines by age,12 as both the B- and T-cell function will be reduced with increasing age.12 In addition, elderly patients are often frailer and have comorbidities affecting infection susceptibility,11 increasing the risk of both morbidity and mortality of the disease and the treatment. Although studies have found that older patients are not more susceptible to infections,13 one must take into account that older patients are often treated with milder and less toxic chemotherapy regimens affecting infectious risk.11 Age and comorbidity burden increase the risk for intensive care unit (ICU) admission,14 and severe comorbidity is a strong predictor for early death in acute leukemia patients, death often caused by infectious complications.15

In recent years, there has also been an increased focus on nutrition, and undernourishment is considered a critical risk for serious infection complications.16 Nutritional problems are often linked to the treatment of leukemia, as nausea, vomiting, and emesis are common treatment side effects. Consequently, reduced food intake and weight loss are often complementarities to the treatment, and reduced nutritional intake increases the risk of serious infections. Low initial body mass index (BMI) and more pronounced weight loss during treatment courses are strong prognostic indicators associated with lower survival and both bacterial and fungal infections.17

Furthermore, global challenges regarding the diagnostic and treatment of infectious complications in acute leukemia patients are also important to take into considerations. For example, for children treated for ALL, the rates of infection-associated mortality are up to 10-times higher in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries.18 This is due to several underlying factors such as shortage of trained personnel, supplies, diagnostic tools, and adequate infrastructures as well as undernourishment and risk of multiple drug-resistant organisms (MDROs).18 Also, in high-income countries, socioeconomic status seems to be a risk factor for infection and early complications in acute leukemia patients.19 Finally, lower early mortality is also registered in centers with larger patients’ volume and more special cancer centers. It may result from differences in the hospital or provider experience and supportive care.20,21

Treatment-related Factors

Treatment of acute leukemia requires intensive chemotherapy with high dose drugs, often in a combination regimen, resulting in prolonged neutropenia, often lasting for weeks.1–3 The risk of developing more serious and complicated infections is clearly linked to the degree and duration of neutropenia.4 The risk of severe infections is not uniform among these patients, and factors associated with increased susceptibility for infectious complications include prolonged neutropenia,22 use of salvage chemotherapy,23 and relapsed disease.24 However, other factors than the leukopenia itself are associated with infectious risk.

Mucosal barriers separate self from non-self and are the first line of defense against external pathogens. Epithelia at mucosal surfaces must allow selective paracellular flux, and at the same time preventing the passage of potentially infectious agents.25 Leukemia patients receiving cytotoxic therapy or radiotherapy will experience mucosal barrier injury, often termed mucositis. The barrier disruption will create an entrance point for resident microorganisms, with the potential to cause bloodstream infections.26 Consequently, the infections are typical due to those opportunistic pathogens that inhabit the skin, oral cavity, and the gastrointestinal tract, rather than more conventional pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumonia (S. pneumonia) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).27

Furthermore, gastrointestinal bacterial colonization will often be affected during the treatment course of acute leukemia, both trough mucosal barrier injuries, and the use of broad spectra antibiotics and other microbial agents.26,28 This will affect the natural bacterial flora of the intestinal tract, often termed the microbiota. Decreases in both oral and feces microbial diversity are associated with the receipt of carbapenem antibiotics.29 Furthermore, loss of microbial diversity throughout treatment is associated with the risk of infection29 and with a higher risk of mortality in the setting of allo-HSCT.30 Clostridium difficile is clearly associated with the use of broad spectra antibiotics, and the risk of clinical infections is increased among leukemia patients and associated with increased mortality.31 In addition, the use of antibiotics sets the patients for risk for colonization with MDROs.32 Colonization with MDROs, especially Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis), Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium), and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (S. maltophilia), has been clearly associated with risk of infections and non-relapse-related mortality in the setting of allo-HSCT in AML patients.33,34 Colonization in the intestine, previous use of antimicrobial therapy, especially beta-lactams and cephalosporins, and total length of hospitalization, all increases the risk of more for MDROs, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase resistance (ESBL)32,35–38 Central venous catheters (CVCs) are an essential tool for an appropriate management of patients with acute leukemia. However, CVCs are an entrance port for bacteria into the bloodstream and a potential for bacterial colonization. CVCs increase the risk for bloodstream infections, and the infection risk is correlated with the numbers of CVC manipulations. The patients are especially vulnerable to gram-positive infections.39 The rate of central-line associated bloodstream infections is estimated to 2/1000 catheter days,40 and delaying CVC placement in acute leukemia does not affect the reduction of infectious risk.41 In contrast, antiseptic coating of intravascular catheters may be effective in decreasing catheter-related colonization and subsequent infections.42 Early removal of CVCs should always be considered for leukemia patients with undocumented sepsis.43 Furthermore, in recent years the use of peripherally inserted central catheters is increasing and is associated with a lower risk of bloodstream infections.44 A study from China in the period 2011–2014 demonstrated that the risk of BSI in the use of peripherally inserted central catheters in cancer patients was 0.05/1000 catheter days, and the overall risk of infections was approximately 1/1000 catheter days.44

Taken together, all factors related to one of these three conditions increase the risk of infections in leukemia patients, and proper evaluation of all these risk factors should be considered when evaluating leukemia patients for prophylaxis and treatment of infectious complications.

Ferbril Netropenia and Sepsis

According to the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock, sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.45 Organ dysfunction is identified as an acute change in the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score.46 Septic shock is defined as a subset within sepsis in which underlying circulatory and cellular/metabolic abnormalities are profound enough to increase the mortality risk substantially. Bacteremia is defined as the growth of bacteria in blood cultures, although infections do not have to be proven to diagnose sepsis at the onset. These criteria also define sepsis in patients with acute leukemia. These patients are especially prone to bacterial infections following chemotherapy due to severe neutropenia,47,48 and their cellular immune defect represents an additional predisposition to infections to fungi, parasites, and viruses. However, leukemic patients are at risk for infectious diseases and can present altered symptoms and signs due to an impaired inflammatory response. Thus a high index of suspicion is warranted.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Leukemic patients may present altered symptoms and signs for sepsis and infections because of an impaired inflammatory response, thus discovering an infection, and the likely focus might represent a major challenge. However, sepsis should be suspected in patients presenting typical signs and symptoms for infections49 including fever (core temperature >38°C), hypothermia (<36°C), heart rate >90 beats per minute, tachypnea (>30 breaths per minute), altered mental status, significant edema or positive fluid balance (>20 ml/kg over 24 hours), or hyperglycemia (plasma glucose >110 mg/dl or 7.7 mmol/l) in the absence of diabetes. Besides, one should be aware of organ-specific symptoms associated with infectious diseases such as respiratory symptoms (cough, rhinorrhea, and respiratory distress), gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain), and consciousness disturbance which all should lead to further diagnostic work-up. Notably, mucositis and cutaneous signs such as rash, local heat, swelling, exudate, fluctuation, or ulceration can manifest infectious diseases in the leukemic patient.

These latter signs will determine the likely source of infection and the status of the organ function. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)-score, Talcott’s classification and the clinical index of stable febrile neutropenia (CISNE) tool could help the assessment of the patients’ risk for developing a serious infection in patients with febrile neutropenia.50 MASCC-score index of <21 indicates a low risk, and the patient could be considered for outpatient treatment with oral antibiotics. With high risk (MASCC>21) or clinical suspicion of sepsis, the patient should always be admitted to the hospital.50 However, it is important to be aware that only a minority of the patients (28%) in the original MASCC-cohort were patients with acute leukemia.51 Direct comparison between CISNE and MASCC-score demonstrates that CISNE gives a more specific identification of low-risk patients, although with lower certainty in patients with acute leukemia.52 The 2016 3.0 sepsis definition recommended qSOFA as a screening tool for patients with suspected sepsis. qSOFA has so far shown inferior sensitivity compared to MASCC-score for risk assessment for sepsis development in neutropenic patients.53,54 Cautious use of scoring systems, and still be clinical vigilant is important, as more validation of these scoring systems are needed, also in leukemia-cohorts.

Hemodynamic parameters can indicate organ dysfunctions and sepsis development; arterial hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, mean arterial pressure <70 mmHg, or a systolic blood pressure decrease of >40 mmHg in adults or <2 standard deviations (SD) below normal for age), mixed venous oxygen saturation >70%, cardiac index >3.5 l/min/m2, arterial hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2<300), and acute oliguria (urine output <0.5 ml/kg/h or 45 ml for at least 2 h).

Laboratory testing helps estimate the severity of the infection and may indicate the source of infection.49 Inflammatory markers indicating sepsis are leukocytosis (white cell counts (WBC) >12 × 109/l), leukopenia (WBC <4 × 109/l), normal white cell counts with >10% of immature forms, and plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) or procalcitonin >2 SD above the normal value/range. Organ dysfunction can also easily be verified in laboratory testing including creatinine increase ≥0.5 mg/dl, coagulation abnormalities (international normalized ratio (INR) >1.5 or activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) >60 seconds), thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100 000/μl), and hyperbilirubinemia (plasma total bilirubin >4 mg/dl or 70 μmol/l). Hyperlactataemia (>3 mmol/l) can indicate decreased tissue perfusion.

Appropriate cultures and Gram-stains (blood, sputum, urine, fluids, and cerebrospinal fluid) are helpful to identify the source of the infection and reveal the microbe. Blood cultures should ideally be taken during fever and before the onset of antibiotics, and are found positive in 40–60% of patients with septic shock. Positive microbial findings can be crucial for the correct treatment of the patient. The chest radiograph will aid in the diagnosis of pneumonia, empyema, and acute lung injury. Abdominal ultrasound or computer tomography (CT) scanning is indicated if abdominal sepsis is suspected, and magnet resonance imaging (MRI) can help find infections in soft tissues. Several factors can affect the outcome of FN, including the patient’s underlying disease, age, patients’ clinical condition, number of infectious foci, duration of the neutropenia, the onset of antimicrobial therapy, geographical location, and local profile of antimicrobial resistance.55

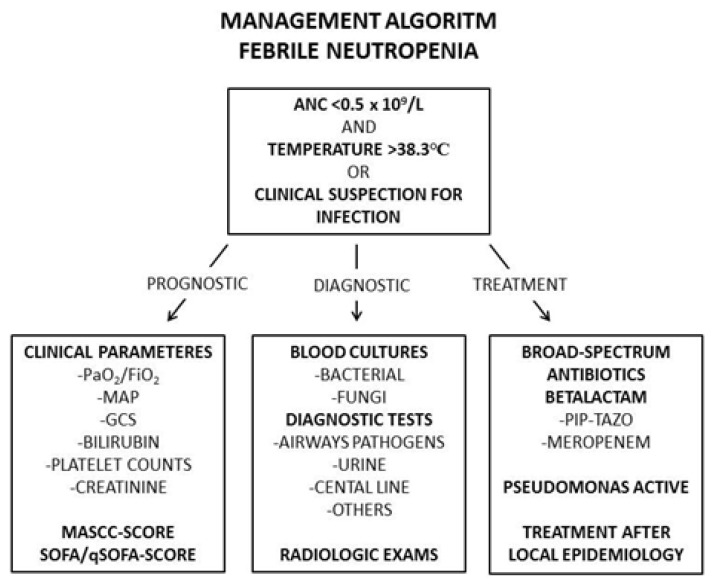

Despite advances in antimicrobial treatment, bloodstream infections (BSIs) prolong hospital stay, increase direct patient care costs, and cause considerable mortality.56,57 In neutropenic patients with fever of unknown origin, the attack rate for BSI is 11%–38%.58 Previous studies showed that infections were the cause of death for 50%–80% of acute leukemia patients, and for 50% of patients with lymphoma and solid tumors.59 In Figure 2, we present an algorithm for the management of FN in leukemia patients, including prognostic, diagnostic, and treatment decision work up.

Figure 2.

Risk factors for infections in patients with leukemia.

The figure illustrate an algorithm for management of FN in leukemia patients, including prognostic, diagnostic and treatment decision work up. Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; C, Celcius; FiO2, Fraction of inspired Oxygen; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; L, liter; MAP, Mean Arterial Pressure; MASCC, Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer; PaO2, Partial pressure of Oxygen; Pip/tazo, piperacillin/tazobactam; qSOFA, quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Bacterial Etiology

Infectious complications in patients with hematological malignancies occur most frequently in patients with chemotherapy-induced cytopenia following intensive chemotherapy,60,61 and FN is most common in AML patients. The etiology is often unknown at the onset of infection.62 Knowledge of the prevalence of causative bacteria in neutropenic patients with fever is important as infections can rapidly progress, and FN patients can become hemodynamically unstable, as prompt and rapid onset of adequate antimicrobial treatment within one hour is recommended.63,64 There are considerable site- and region-specific differences in the incidence of resistant organisms such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE). These local differences may impact the initial choice of empiric antibiotic therapy. Therefore, knowledge of the general and local epidemiology and resistance profiles is of paramount importance in the optimal treatment of febrile neutropenia.65,66 The most frequent bacteria causing infections in acute leukemia patients are summarized in Table 1.67–84

Table 1.

Most common bacteria causing infection in acute leukemia patients.

The most frequent Gram-positives and Gram-negatives causing infections in acute leukemia patients are summarized in the Table. The table presents the most important microbes, their main source for entrance and the possible antimicrobial drugs of choice.

| Microbes | Source | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive microbes |

S. aureus -MSSA -MRSA |

CVC, skin | [67, 68] |

| CoNS | CVC, skin | [69] | |

|

E. faecalis E. faecium |

GI-tractus, CVC | [70] | |

| C. difficile | Lower GI-tractus | [71] | |

| Viridans group streptococcus | Oral/GI-tractus | [72–75] | |

| S. pneumoniae | Nasal cavity | [72–75] | |

| Gram-negative microbes | E.coli | GI-tractus, urogenital | [70, 76–81] |

| Klebsiella spp. | GI-tractus, urogenital | [70, 76–81] | |

| A. baumanii | Skin, catheters, environment | [82] | |

| P. aeruginosa | GI-tractus, environment | [70, 83, 84] |

Abbreviations: MRSA: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. MSSA: Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. CoNS: Coagulasenegative Staphylococcus. VRE: Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci.

Previous studies have documented bloodstream infections in 15–38% of patients with hematological malignancies.62,85–87 In Europe and the US, Gram-negative organisms were the most predominant pathogens during the 1970s and the 1980s, followed by a shift toward Gram-positive organisms.86 In 2000, 76% of all BSI in the US was associated with Gram-positive microbes, of which coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), viridans streptococci and enterococci were the most frequently isolated pathogen.87 Recently, a number of reports show a tendency towards an increase of Gram-positive bacteremia.62,85–87 This is usually attributed to the increasing use of indwelling CVCs and the use of fluoroquinolone (FQ) prophylaxis which suppresses the aerobic Gram-negative organisms of the gastrointestinal tract. Mortality is lower in patients with Gram-positive bacteremia than in patients with Gram-negative bacteremia.86 Epidemiological studies of BSI rank Gram-negative rods with Escherichia coli (E. coli) as the most frequently isolated pathogen.86 More recently, the increased incidence of MDROs, such as Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae, has been the scope of several papers.88,89 Gram-negative bacteria are reported as MDROs if not susceptible to at least three of the following antimicrobial categories: antipseudomonal penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides or FQs.90 In several European countries, >10% of invasive infections caused by E. coli were due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL).66,91 Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a Gram-negative pathogen associated with high mortality, and accounts for approximately 5–10% of BSI in hematological patients.92 P aeruginosa is characterized by several resistance mechanisms; (i) intrinsically resistant to antimicrobial agents due to low permeability of its cell wall, (ii) genetic capacity to express a vast repertoire of resistance mechanisms, (iii) become resistant through mutations in regulative resistance genes, and (iv) acquire additional resistance genes from other organisms via plasmids, transposons and bacteriophages.93

Carbapenem resistance is reported as high as 3–51% in different geographical regions of Europe.91 Acinetobacter has emerged as a significant cause of health-care-associated infection in critically ill and immunocompromised patients. Mortality rank between 17–50% and Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is estimated to be responsible for about 2–12% of BSI.91 Oral mucositis, use of CVC and FQ prophylaxis increase the risk of Gram positive BSI. The most frequent isolated pathogen is staphylococcus spp, dominated by CoNS that accounts for about 25%–33% of all BSI.94,95 The more virulent, S. aureus is responsible for only a smaller proportion of infections, accounting for about 5% of BSI.86 The incidence of methicillin resistance is higher in CoNS than in S. aureus, the median resistance rate of 80% and 56% respectively, and >60% of European centers reporting more than 50% methicilline-resistance in CoNS.91,92

Enterococcus spp. is now the third most frequent group of pathogens in BSI and affects 10–12% of transplant patients. Many centers report a shift from E. faecalis to E. faecium, the latter being frequently resistant to ampicillin and demonstrate increasing resistance to vancomycin (10.4% in 2014 and 14.9% in 2017).96 The mortality rate is high, and in one study from a transplant center in the US, they found a 30-day mortality of 38%.97 Noteworthy, enterococcus spp. in general have low virulence, and BSI with enterococcus spp. have been clearly associated with severe comorbidity, and their direct impact on mortality remains unclear.96,98

The frequency of viridans streptococci in BSI of neutropenic patients with cancer has significantly increased over the last 10–15 years and now accounts for approximately 5 %.87,99 Risk factors in this patient population include severe neutropenia, oral mucositis, administration of high-dose cytosine arabinoside, and concomitant use of antimicrobial prophylaxis with either trimethoprim-sulfa or an FQ. Viridans streptococci may contribute to acute respiratory distress syndrome; in some studies, mortality rates of 10% have been reported.100

Treatment of Bacterial Infections

FN is a medical emergency, and early identification followed by diagnostic blood cultures and prompt administration of appropriate intravenous antibiotics remains the cornerstones in the initial management. Harvesting microbiological cultures and source control obtained by removal or drainage of the infected foci is mandatory. Empiric antibiotic treatment should be started within the first hour after the clinical suspicion is raised, according to guidelines for neutropenic fever and sepsis.50 When a causative microbe is diagnosed, a more targeted antibiotic treatment could be possible, resulting in more specific and less broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. The main antibiotics and their characteristics are presented in Table 2.50,67,68,70,71,73–81,101–109

Table 2.

Main antibiotics for infection treatment.

The table the most relevant antibiotics when treating infections in leukemic patients. The table present the most used drugs, their antimicrobial specter and main advantages and disadvantages in clinical practice.

| Generic | Antimicrobial specter | Drugs | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-lactams | Penicillin | Gram-positives Some anaerobes |

Penicillin G | Low toxicity Less resistance driving than cephalosporines |

Narrow spectrum | [73–75] |

| Aminopenicillin | Gram-positives, also most E. Faecalis Some Gram-negatives |

Ampicillin | Less resistance driving than cephalosporines Cover most enterococci |

Relative narrow spectrum | [101] | |

| Penicillinase stable penicillin | Gram-positives | Cloxacilline | Less resistance driving than cephalosporines | Narrow spectrum | [67] | |

| Cephalosporins, no Psedumonas or MRSA activity | Covering both Grampositive and Gramnegative, but not ESBL, P. aeruginosa or MRSA | Cefotaxime Ceftriaxone |

Beta-lactam alternative for susceptible microbes | No effect against ESBL-producing microbes | [107–109] | |

| Cephalosporins Pseudomonas active | Gram-negatives P. aeruginosa Fewer Gram-positives |

Ceftazidime Cefepime |

Beta-lactams approved as first treatment for neutropenic fever | Ceftazidime give no effect against MSSA | ||

| Cephalosporins MRSA active | Gram-negatives Gram-positives MRSA |

Ceftobiprol Ceftraroline |

Alternative Beta-lactam with MRSA effect | Not approved in neutropenic fever | ||

| Carbapenems | Gram-negatives also ESBL Gram-positives Anaerobes No MRSA coverage |

Meropenem Ertapenem Imipenem |

Broad spectrum, also ESBL and anaerobes no effect against enterococci and MRSA Less cross-reactivity for penicillin-allergies’ | Resistance driving | [70, 76–81] | |

| Betelactams with enzyme inhibitors | Gram-negatives also ESBL Gram-positives Anaerobes |

Piperacillin-Tazobactam. Ceftazidime-Avibactam. Ceftolozane-Tazobactam. Imipenem-Cilastine. |

Pip-Tazo good choice for first line treatment in neutropenic fever Extended broad spectrum, also ESBL and anaerobes |

Cross-reactivity for penicillin-allergies | [102] | |

| Non-Beta-lactams | Metronidazole | Anaerobes C. difficile |

Metronidazol | Anaerob coverage to primary regime Effect against clostridium |

Neuropathies | [71] |

| Aminoglycosides | Gram-negatives Gram-positives |

Gentamicin Netilmicin Tobramycin |

Rapid antimicrobial effect Broad spectrum Little resistance driving |

Nephrotoxicity Ototoxicity Small therapeutic window |

[103] | |

| Fluoroquinolons | Gram-negatives | Ciprofloxacin Levofloxacine Moxifloxacin |

God penetration in bone, abscesses | Increasing resistance | [50, 101] | |

| Glycopeptides | Gram-positives, MRSA, enterococci, CoNS, C. difficile | Vankomycin Teikoplanin Dalbavicin |

Often alternative for MRSA; enterococci, CoNS | Nephrotoxicity | [67, 68] | |

| Oxazolidinones | Gram-positives, MRSA, VRE, CoNS | Linezolide | Good per oral availability | Bone marrow suppression Neuropathies Lactic acidosis |

[67, 68] | |

| Daptomycin | Gram-positives, MRSA, VRE, CoNS | Daptomycin | Well tolerated | Poor oral absorption Poor effect in pneumonia |

[67, 68] | |

| Polymyxines | MDR Gram-negatives including P. aeruginosa, A. baumanii, CRE | Colistin Polymyxin B |

Nephrotoxicity Neurotoxisity |

[104] | ||

| Fosfomycin | Gram-negatives | Fosfomycin | Alternative as adjuvant in MDR | Resistance development during treatment | [105] | |

| Trimetoprim/Sulfonamides | Gram-negatives MRSA/MSSA, S. maltophilia P. jirovecii, | Trimetoprim-sulfa | Nephrotoxicity | [106] |

Abbreviations: ESBL: Broad-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. CPE: Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. MRSA: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. MSSA: Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. CoNS: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. VRE: Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci.

Adjuvant sepsis-treatment as fluids therapy is important in sepsis treatment, although secondary to antibiotic treatment and adequate source control.110 However, optimization of hemodynamically unstable patients, including volume support supplemented with a vasopressor, inotropic and transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) in case of persistent hypo-perfusion has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality and can prolong survival and improve quality of life.45,111

International recommended empiric treatment of neutropenic fever

International recommended empiric treatment for FN is initial broad covering with pseudomonas acting beta-lactam antibiotic.50,81,90,112,113 In cases of septic shock, guidelines recommend two Gram-negative acting antibiotics, usually a beta-lactam and an aminoglycoside. Traditionally a cephalosporin or piperazillin-tazobactam is recommended, although this is challenged by the rapid spread of MDROs making carbapenem treatment necessary.70,76,77 This is, however not only the case, as other treatment narrower antibacterial spectra are used in some centers.90 The emergence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) also makes the carbapenems less secure choice in several parts of the world.78–81 Escalation or de-escalation strategies are the two main approaches for treatment, depending on the clinical condition of the patient (Table 3).50,81,90,112,113 In an escalation strategy, treatment is initiated with less broad coverage, although escalation is performed if the patient responds inadequately to the initial treatment. With de-escalation strategy, broader antimicrobial therapies initiate the treatment, and if the patient’s condition improves de-escalation is performed. Both strategies depend on the correction of treatment after appropriate microbiology results. With the rapid increase of MDROs, all centers treating leukemia patients should carefully follow and monitor for emerging resistant microbes and use the most appropriate treatment, given local epidemiology.

Table 3.

Treatment strategies for empiric antibiotic treatment in acute leukemia patients.

The table shows the main escalation and deescalation therapy in acute leukemia patients, the different patient groups suitable for the different strategies and recommended empiric therapy.

| Patient group | Recommended empiric therapy | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escalation strategy | All patients, unless criteria for de-escalation approach are present | Anti-pseudomonal cephalosporin (cefepime, ceftazidime) or piperacillin-tazobactam. Other possible options, depending on local epidemiology: Ticarcillin-clavulanate Cefoperazone-sulbactam Piperacillin + gentamicin |

[50, 81, 90, 112, 113] |

| De-escalation strategy | Increased risk for resistant bacteria, such as:

|

Carbapenem (or a new beta-lactam such as ceftolozane/tazobactam or ceftazidime/avibactam) Combinations, examples

|

[50, 81, 90, 112, 113] |

Guidelines used for febrile neutropenia are based on best available data, and a challenge is that studies for febrile neutropenia are usually not specific for leukemia. In Table 4 we have indicated the main population in the studies supporting the current guidelines. Because patients with solid tumors show different phenotypes and different etiology, direct interpretation from these studies should be careful. We have emphasized the description of the microbiological etiology in the previous section because the suspected pathogenic microbe is decisive when starting treatment. However, both the microbiology and health organization varies in different countries, regions and departments. Monitoring the local microbiology and correction of local guidelines, and always try to choose the lesser resistance driving treatment alternative is important. Recommendations given in the next section reflect this, where the treatment of different resistant microbes are described.

Table 4.

Treatment options for special problematic microbes.

The table shows treatment recommendation for microbes associated with special treatment challenges in patients with acute leukemias. The table is based on European (ECIL) and American (IDSA) recommendations, and references to relevant studies are given in the table. First line treatments are listed first, while second line alternatives are given in parentheses.

| Problematic microbes | Recommended antibiotic treatment options | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negatives | ESBL | Carbapenems | [70, 76, 77, 114] HSCT, 1;C, 1;H, 1;H |

| CPE | Two or more active agent combinations; aminoglycosides, polymyxins, tigecycline, fosfomycin, and meropenem | [70, 78–81] HSCT, 1;I, 1;I, | |

| P. aeroginosa | Combination therapy, using beta lactam with aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone | [70, 83, 84] HSCT, 1;HSCT, 1;H | |

| S. maltophilia | Trimetoprim-sulfa (Combination with either ticarcillin/clavulanate or ceftazidime) | [115] I | |

| MDRO A. baumanii | Colistin combination with ampicillin/sulbactam or imipinem or meropenem. Tigecycline combinations. | [82] I | |

| Gram-positives | CoNS | Glycopeptides; vancomycin and teicoplanin (daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline) | [69] HSCT |

| MRSA | [68] I | ||

| VRE | Linezolid and daptomycin (Quinupristin– dalfopristin, tigecycline, fosfomycin, tedizolid, oritavancin, dalbavancin and telavancin). | [70] HSCT |

Abbreviations: ESBL: Broad-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. CPE: Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. MRSA. CoNS: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. VRE: Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci. Indications of febrile neutropenia publications’ main weighting/patient cohort are demonstrated: H; Hematological cohorts, L; Leukemia cohorts, HSCT; Hematological stem cell transplantation, C; Mixed Cancer (both hematological and solid), I; infections, not neutropenia in general

Different local resistance patterns require adaptations of the empirical treatment

When a specific pathogen is identified, the treatment should be corrected according to resistance as long as the microbiology result is clinically plausible.81 Before a definitive resistance pattern is given, one will direct treatment after the local resistance patterns for the identified microbe. Relevant antibiotic treatment for unique problematic microbes based on the latest European and American guidelines are presented in Table 4.68–70,76–84,114,115

The first choice for treating ESBL is carbapenems, beta-lactams with a time-dependent bactericide effect.70,76,77 Aminoglycosides might also have an effect, although many ESBL-strains harbor resistance to aminoglycosides.92 Aminoglycosides have a concentration-dependent bactericide effect depending on peak-concentration and a rapid bactericide effect, in addition, to being synergistic to beta-lactams.103

CPE requires a combination of at least two antibiotics.78–81 The choices are limited and include high dose prolonged meropenem, aminoglycosides, polymyxins, tigecyclin and fosfomycin, depending on the resistance pattern. High dose of meropenem increases the risk for side effects; nephrotoxicity of aminoglycosides and polymyxins could be challenging, while resistance development during treatment is a significant disadvantage for tigecyclin and fosfomycin.

P. aeruginosa is often susceptible to pseudomonas active cephalosporines and piperazillin/tazobactam, although it will often develop resistance during treatment.70,83,84 Meropenem will also be a suitable choice and double coverage with additional aminoglycoside should be considered, especially in unstable patients and if anti-pseudomas drugs are previously used.116 Tobramycin is the recommended aminoglycoside, as high dose gentamycin no longer is regarded as sufficient even with dosages of 7mg/kg. Gentamycin is now proposed to be removed from The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) clinical breakpoints for Pseudomonas spp.

MDRO A. baumani will often be difficult to treat, and represent a major challenge in the treatment of leukemia patients if present.82

CoNS are frequently found in catheter infection and BSI. Although not always very virulent, CoNS might be difficult to treat due to resistance.69 Vancomycin is often the first treatment of choice, although treatment has to be corrected after susceptibility-pattern. Cloxacilline, daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline are possible alternatives.

The MRSA incidence is varying from region to region, and coverage for MRSA empirically should be considered according to local incidence.68 MRSA could be treated with vancomycin and daptomycin, although newer MRSA-active cephalosporins have been developed. Other alternatives are linezolid and tigecycline.

VRE are not very virulent but have a difficult susceptibility-pattern.70 Alternative treatments include linezolid and daptomycin. Alternatives are quinupristin–dalfopristin, tigecycline, fosfomycin, tedizolid, oritavancin, dalbavancin and telavancin.

The net antibiotic consumption in society, both for human and animal use is one of the most important predictors for the spread of antibiotic resistance.117 Acute leukemia patients are maybe the most vulnerable of all patients, and among the individuals that easiest acquire resistant microbes due to their immunocompromised state.70 Acute leukemia patients are in need of broad antibiotic coverage, although at the same time, they are more vulnerable to side effects. The ideal treatment should hence be exposure of antimicrobial agents with as narrow antimicrobial specter for as short time as possible. Faster microbiology service has made it possible to faster escalation or de-escalation of the treatment, depending on the chosen treatment strategy.

Norwegian antibiotic-recommendations for treatment of neutropenic fever are penicillin and aminoglycoside contrary to international recommendations.72–75 International studies show that aminoglycoside treatment increases the risk of nephrotoxicity compared to beta-lactam treatment. However, studies from countries with a low prevalence of MRDOs like Norway, indicate safety with penicillin and aminoglycoside empiric treatment, given early reconsideration and escalation when necessary.72,74 However, significant numbers of patients treated with this regime need treatment alterations, although overall mortality is not increased compared to other studies of FN.72

Invasive Fungal Infections

Invasive fungal infection (IFI) represent an important cause of treatment failure in adults with acute leukemia, and the cumulative probability of developing IFI after a diagnosis of acute leukemia has been estimated to 11.1% at 100 days.118 IFI is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with acute leukemia, and patients treated for hematologic malignancies, and develop a complicating IFI, have an estimated cause specific mortality due to IFI of 35–38 %.119,120 AML constitutes the hematologic malignancy with the highest risk of associated IFI. In a report from 2006, Chamilos and coworkers found IFI in 314 of 1017 (31%) autopsies of patients diagnosed with hematologic malignancies, of which only 25% had been diagnosed with IFI while the patients were alive.121

Data from previous studies have demonstrated; (i) the incidence of IFIs in patients with hematologic malignancies has increased, (ii) over half of IFIs emerge during the remission induction chemotherapy,122 (iii) higher age, use of corticosteroid, ANC <0.1 × 109/L at the time of IFI diagnosis, lack of recovery from aplasia, multiple pulmonary localizations of infection and presence of indwelling catheters all negatively influence outcome of IFI.123,124

The most frequently isolated yeast and mold spp. in patients with acute leukemias are presented in Table 5. The incidence of the most common fungal infections in patients with acute leukemia has changed in the last decade,125 and the incidence of yeast and mold infections show epidemiological variations between regions, depending on the patient population, risk factors and use of antifungal therapy. In certain geographical regions, an association between the incidence of IFI, prevalent diseases, and host factors exists. The occurrence of cryptococcal and Pneumocystis jirovecii (P. jirovecii) infections are reported in regions with a high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),126,127 and diabetes is a risk factor for invasive mold infections.128 In mold infections, environmental factors predispose patients for invasive infections, with hospital outbreaks linked to the use of contaminated instruments and devices, Blastomycosis is associated with occupational exposure (e.g., forest rangers) and recreational activities (e.g., camping and fishing).128,129

Table 5.

Major invasive fungal infections in patients with acute leukemia.

The table presents the most important fungus, divided in molds, yeasts and mucormycosis, and their main subclasses causing infection in acute leukemia patients.

| Molds | Aspergillus spp. | A. fumigatus |

| Fusarium spp. |

F. solani F. oxysporum F. verticillioides F. proliferatum |

|

| Yeasts | Candida spp. |

C.albicans C. glabrata C. kruesei C. tropicalis C. parapsilosis |

| Cryptococcus spp. |

C. neoformans C. gattii C. albidus C. uniguttulatus |

|

| Tricosporon spp. |

T. asahii T. mucoides T. asteroides |

|

| Pneumocystis spp. | P. jirovecii | |

| Mucormycosis | Rhizopus spp Mucor spp Rhizomucor spp Lichtheimia |

R. arrhizus M. circinelloides Rhizomucor spp L. corymbifera |

Candida albicans (C. albicans) was most frequently isolated in blood cultures in the ‘80s and ’90s. Since the introduction of fluconazole prophylaxis in hematology units, there has been a gradual shift from C. albicans to non-C.albicans strains.130 Candida spp. that are fluconazole-resistant (C. krusei) or susceptible–dose-dependent (C. glabrata) currently account for >80% candidiasis episodes in some hematology units.131,132

A large concurrent surveillance study, Surveillance and Control of Pathogens of Epidemiological Importance (SCOPE), was used to examine the secular trends in the epidemiology and microbiology of nosocomial BSIs. They found Candida spp. to be the fourth most common isolated pathogen causing BSIs, and C. albicans was the overall most frequently isolated pathogen.133 Invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies and in patients undergoing allo-HSCT is still associated with high morbidity and mortality.122,134 There have also been an increase in non-Aspergillus fumigatus (A. fumigatus) spp., and other mold infections, i.e. Fusarium and Mucormycosis.135 The emergence of C. auris that show resistance to most known antifungals is still not frequent, although it might present as a significant problem in the future.136

In a study from Houston, incidence and risk factors for breakthrough invasive mold infections (IMI) in AML patients receiving remission induction chemotherapy were investigated. 17 % of the patients had a possible IMI and only 3.7 % a proven diagnosis of IMI. The incidence of proven or probable IMI per 1000 prophylaxis-days was not statistically different between anti-Aspergillus azoles and micafungin. Older age and relapsed/refractory AML diagnosis were associated with IMI on multivariable analysis.137 Introduction of echinocandins and more recently introduced azoles may have contributed to evolve the epidemiology of candidiasis, as incidences of both C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis have increased in some treatment centers.124,138

Treatemnt of Fungal Infections

Fungal treatment could either be empiric, diagnostic driven or directed.139 Empiric therapy is used in centers where diagnostics are unavailable, and include broad covering with antifungal treatment after persisting fever for 5–7 days in neutropenic patients, despite antibiotic treatment. The European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL)-guidelines recommend either caspofungin or liposomal amphotericin B for empiric treatment.140 In diagnostic driven treatment, antifungal therapy is started if early markers of fungal infections are presented. Markers for fungal infection used in clinical practice include positive galactomannan (GM)-test; positive beta-D-glucan (BDG)-test, PCR-screening and radiological examinations. Directed therapy is given patients with proven fungal disease.

For invasive candidiasis, echinocandins are first line treatment, although stepdown treatment to i.e. fluconazole, is recommended after susceptibility test results are available.141 Voriconazole, or now recently added isavuconazole, are first line treatment for invasive aspergillosis.140 Isavuconazole has shown non-inferiority compared to voriconazole, although it has so far shown significantly fewer side effects.142 Treatment of mucormycosis is challenging and often includes surgical debridement if possible. Liposomal amphotericin B is first line treatment.140,143 P. jirovecii is normally treated with trimethoprim-sulfa as long as the treatment is tolerated.106 Other alternatives for treatment of fungal infections, various fungicides and their antifungal spectrum and important pharmacological properties are presented in Table 6,140–142,144 and treatment of special problematic fungal infections are presented in Table 7.106,140–143

Table 6.

Main antifungal treatment options.

The table demonstrates the main treatment classes of antifungal therapy; azoles, echinocandins and amphotericin. The most important drugs in each class, their main antifungal specter and main advantages and disadvantages are presented from left to right.

| Drugs | Antifungal specter | Advantages | Disadvantages | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azoles | Fluconazole |

C.albicans, C.tropicalis, C.parapsilosis, C.glabrata (30–40% resistant) C. neoformans |

Good oral bioavailability Good CNS penetration |

Substantial drug interactions Substantial C. glabrata resistance Fungustatic, not fungicide |

[141] |

| Voriconazole | Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., Fusarium spp. | Used for treatment of Aspergillus | 15–50% cross resistance to fluconazole Substantial drug interactions Therapeutic drug monitoring recommended in severe disease |

[140] | |

| Posakonazole | Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., | Used for prophylaxis for Aspergillus | Substantial drug interactions | [144] | |

| Isavuconazole | Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp, | Better tolerated than Voriconazol | Substantial drug interactions New medicament |

[142] | |

| Echinocandins | Caspofungin | Fungicide: Candida spp. Fungostatic: Aspergillus spp. |

Alternative for treatment of aspergillus No dose reduction for renal failure Few drug interactions |

Low CNS and bone penetration No urine secretion | [141] |

| Mikafungin | Fungocide: Candida spp. Fungostatic: Aspergillus spp. |

No dose reduction for renal failure Few drug interactions |

Low CNS, eye and bone penetration No urine secretion | [141] | |

| Anidulafungin | Fungocide: Candida spp. Fungostatic: Aspergillus spp. |

No dose reduction for renal failure Less drug interactions |

Low CNS and bone penetration No urine secretion Not evaluated for invasive Aspergillus |

[141] | |

| Amphotericin | Amphotericin B | Candida spp. Aspergillus spp. C. neoformans |

Lipid formulation most widely use due to less side effects | Nephrotoxicity, Electrolyte imbalance Anemia |

[140] |

Table 7.

Treatment options for special problematic fungus.

The table shows treatment recommendation for fungus associated with special treatment challenges in patients with acute leukemias. The table is based on European (ECIL) and American (IDSA) recommendations, and references to relevant studies are given in the table. First line treatments are listed first, while second line alternatives are given in parentheses.

| Problematic microbes | Recommended antifungal treatment options | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive fungal infections | P. jiroveci | Trimetoprim-sulfa (Primaquine + clindamycin, pentamidine) | [106] I |

| Candida spp. | Ecinocandins (Fluconazole) | [140, 141] L, 1;HSCT | |

| Aspergillus spp. | Voriconazole, isavuconazole (Liposomalt amphotericin B, caspofungin) | [140] L, 1;HSCT | |

| Mucormycosis | Liposomalt Amphotericin B (Posakonazole, combination) | [140, 142, 143] L, 1;HSCT | |

Indications of febrile neutropenia publications’ main weighting/patient cohort are demonstrated: H; Hematological cohorts, L; Leukemia cohorts, HSCT; Hematological stem cell transplantation, I; infections, not neutropenia in general.

Prophylaxis of Bloodstream Infection and Fever During Neutropenia

Patients with acute leukemias are at risk of developing severe infections related to previously discussed factors (Figure 1). In the absence of preventive measures, 48–60% of the patients who became febrile have an established or occult infection.145

The use of antibiotic prophylaxis has been discussed widely in both Europe and US. According to European and American guidelines, FQs have been recommended as prophylaxis during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in patients with expected neutropenic periods above seven days.84 In consideration of increased antibiotic resistance, the role of FQ prophylaxis has been reevaluated. A meta-analysis based on two randomized clinical trials and 12 observational studies published between 2006 and 2012 concluded with a reduction of cases with BSI, although without effect on overall mortality rate. Some of the studies also found increased numbers of colonization or infections with MDROs.84

The increased frequency of E. coli resistance with increased FQ use is well documented and results mainly form mutations in topoisomerase genes or changes in the expression of efflux pumps. It may also be transmitted by plasmids which can transfer ESBL at the same time. The use of FQ has also been linked to the proliferation of several other MDROs such as MRSA, VRE and C. difficile.146,147 However, patients at high risk of FN should be considered for antimicrobial prophylaxis, including patients with acute leukemias. The risk stratifications should be based on patient characteristics, i.e., advanced age, performance status, nutritional status, prior FN, comorbidity, and their underlying leukemia.148

In contrast, most patients should not be considered for antifungal prophylaxis, except those that are at risk for profound protracted neutropenia, i.e. relapsed/refractory AML patients or patients undergoing allo-HSCT. These latter patient groups should receive prophylaxis with an oral azole or parenteral echinocandin.148,149

Other Causes of Persistent Fever and Their Management

Occasionally fever may be the only sign of an ongoing infection or non-infectious process in patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia; other decisive signs and symptoms of inflammation (erythema, swelling, pain, infiltrates) may be absent. The febrile response is non-specific, and concomitant use of antipyretic drugs (corticosteroids, paracetamol) may suppress fever. As FN is a medical emergency, it is crucial to accurately substantiate the differential diagnosis, as they require different treatment strategies.

Fever in acute leukemia patients can also be attributed to by one of the following reasons; (i) drug fever, (ii) tumor fever (iii) thrombosis, or (iv) rheumatologic disorders. Drug fever is associated with eosinophilia, acute interstitial nephritis, drug-induced hepatitis and disappears rapidly after discontinuation of the particular drug.150 Tumor fever is one of the most common causes of non-infectious pyrexia in febrile patients with malignancy, and may also occur in leukemia.151 Thrombosis is always important to be aware of, as malignancy is a main risk factor for the development of thrombosis.152 Rheumatologic disorders are also associated with the clinical manifestations of a number of solid and hematological diseases and represent an important clue during the early diagnosis and treatment of the cancer diseases.153

Conclusions

Acute leukemias are a group of malignant blood disorders characterized by a serious clinical course, and the only treatment with curative potential is intensive chemotherapy, possibly combined with allo-HSCT. Infections are important complications to both the diseases themselves and their therapy. Thoroughly diagnostic workup, including microbiological sampling, is the fundament of further handling and treatment. Improvements in both treatment and prophylaxis against both bacterial and fungal infections have helped to improve the treatment results for acute leukemia patients. On the other hand, resistance development to an increasing proportion of the antimicrobial agents we have available is of considerable concern, and this, in turn, can lead to increased morbidity and mortality among leukemia patients from infectious complications. Therefore, physicians, who are treating this specific patient group, must be carefully aware of this increasing problem and make thorough considerations when choosing antimicrobial therapy. In order to make leukemia treatment less toxic, and thereby reduce the risk of serious infections, new searches for new and improved antimicrobial agents are important to further improve treatment outcomes among patients with acute leukemia.

The noteworthy, infectious complication and early mortality seem to be declining with time,19 since the diagnostic precision, prophylaxis and treatment have increased over the past decades. However, this is currently challenged by the increased risk of resistance development.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

References

- 1.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1136–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(6):e577. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan M, Siddiqi R, Naqvi K. An update on classification, genetics, and clinical approach to mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) Ann Hematol. 2018;97(6):945–953. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodey GP, Buckley M, Sathe YS, Freireich EJ. Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1966;64(2):328–340. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-64-2-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166(1):678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashman LK, Drew PA, Toogood IR, Juttner CA. Immunological competence of patients in remission from acute leukaemia: apparently normal T cell function but defective pokeweed mitogen-driven immunoglobulin synthesis. Immunol Cell Biol. 1987;65(Pt 2):201–210. doi: 10.1038/icb.1987.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswal S, Godnaik C. Incidence and management of infections in patients with acute leukemia following chemotherapy in general wards. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:310. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czyzewski K, Galazka P, Fraczkiewicz J, Salamonowicz M, Szmydki-Baran A, Zajac-Spychala O, Gryniewicz-Kwiatkowska O, Zalas-Wiecek P, Chelmecka-Wiktorczyk L, Irga-Jaworska N, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal disease in children after hematopoietic cell transplantation or treated for malignancy: Impact of national programme of antifungal prophylaxis. Mycoses. 2019;62(11):990–998. doi: 10.1111/myc.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hale KA, Shaw PJ, Dalla-Pozza L, MacIntyre CR, Isaacs D, Sorrell TC. Epidemiology of paediatric invasive fungal infections and a case-control study of risk factors in acute leukaemia or post stem cell transplant. Brit J Haematol. 2010;149(2):263–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Styczynski J, Czyzewski K, Wysocki M, Gryniewicz-Kwiatkowska O, Kolodziejczyk-Gietka A, Salamonowicz M, Hutnik L, Zajac-Spychala O, Zaucha-Prazmo A, Chelmecka-Wiktorczyk L, et al. Increased risk of infections and infection-related mortality in children undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared to conventional anticancer therapy: a multicentre nationwide study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):179 e171–179 e110. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ossenkoppele G, Lowenberg B. How I treat the older patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(5):767–774. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-551499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller L, Di Benedetto S, Pawelec G. The Immune System and Its Dysregulation with Aging. Subcell Biochem. 2019;91:21–43. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-3681-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fanci R, Leoni F, Longo G. Nosocomial infections in acute leukemia: comparison between younger and elderly patients. New Microbiol. 2008;31(1):89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halpern AB, Culakova E, Walter RB, Lyman GH. Association of Risk Factors, Mortality, and Care Costs of Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia With Admission to the Intensive Care Unit. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(3):374–381. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Djunic I, Virijevic M, Novkovic A, Djurasinovic V, Colovic N, Vidovic A, Suvajdzic-Vukovic N, Tomin D. Pretreatment risk factors and importance of comorbidity for overall survival, complete remission, and early death in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology. 2012;17(2):53–58. doi: 10.1179/102453312X13221316477651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tvedt TH, Reikvam H, Bruserud O. Nutrition in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantion--Clinical Guidelines and Immunobiological Aspects. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2016;17(1):92–104. doi: 10.2174/138920101701151027163600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumgartner A, Zueger N, Bargetzi A, Medinger M, Passweg JR, Stanga Z, Mueller B, Bargetzi M, Schuetz P. Association of Nutritional Parameters with Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Undergoing Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Ann Nutr Metab. 2016;69(2):89–98. doi: 10.1159/000449451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caniza MA, Odio C, Mukkada S, Gonzalez M, Ceppi F, Chaisavaneeyakorn S, Apiwattanakul N, Howard SC, Conter V, Bonilla M. Infectious complications in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated in low-middle-income countries. Expert Rev Hematol. 2015;8(5):627–645. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2015.1071186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho G, Jonas BA, Li Q, Brunson A, Wun T, Keegan THM. Early mortality and complications in hospitalized adult Californians with acute myeloid leukaemia. Brit J Haematol. 2017;177(5):791–799. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho G, Wun T, Muffly L, Li Q, Brunson A, Rosenberg AS, Jonas BA, Keegan THM. Decreased early mortality associated with the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia at National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers in California. Cancer. 2018;124(9):1938–1945. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez EM, Malogolowkin M, Li Q, Brunson A, Pollock BH, Muffly L, Wun T, Keegan THM. Decreased Early Mortality in Young Adult Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated at Specialized Cancer Centers in California. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(4):e316–e327. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill S, Carney D, Ritchie D, Wolf M, Westerman D, Prince HM, Januszewicz H, Seymour JF. The frequency, manifestations, and duration of prolonged cytopenias after first-line fludarabine combination chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(2):331–334. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolach O, Itchaki G, Bar-Natan M, Yeshurun M, Ram R, Herscovici C, Shpilberg O, Douer D, Tallman MS, Raanani P. High-dose cytarabine as salvage therapy for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia--is more better or more of the same? Hematol Oncol. 2016;34(1):28–35. doi: 10.1002/hon.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zajac-Spychala O, Skalska-Sadowska J, Wachowiak J, Szmydki-Baran A, Hutnik L, Matysiak M, Pierlejewski F, Mlynarski W, Czyzewski K, Dziedzic M, et al. Infections in children with acute myeloid leukemia: increased mortality in relapsed/refractory patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1616185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.France MM, Turner JR. The mucosal barrier at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(2):307–314. doi: 10.1242/jcs.193482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Velden WJ, Herbers AH, Netea MG, Blijlevens NM. Mucosal barrier injury, fever and infection in neutropenic patients with cancer: introducing the paradigm febrile mucositis. Brit J Haematol. 2014;167(4):441–452. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klastersky J, Ameye L, Maertens J, Georgala A, Muanza F, Aoun M, Ferrant A, Rapoport B, Rolston K, Paesmans M. Bacteraemia in febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30(Suppl 1):S51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S, Covington A, Pamer EG. The intestinal microbiota: Antibiotics, colonization resistance, and enteric pathogens. Immunol Rev. 2017;279(1):90–105. doi: 10.1111/imr.12563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galloway-Pena JR, Smith DP, Sahasrabhojane P, Ajami NJ, Wadsworth WD, Daver NG, Chemaly RF, Marsh L, Ghantoji SS, Pemmaraju N, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal microbiome in infectious complications during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2186–2196. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L, No D, Gobourne A, Viale A, Dahi PB, et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;124(7):1174–1182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo R, Greenberg A, Stone CD. Outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized leukemia patients: a nationwide analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(7):794–801. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Vidal C, Cardozo-Espinola C, Puerta-Alcalde P, Marco F, Tellez A, Aguero D, Romero-Santana F, Diaz-Beya M, Gine E, Morata L, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with acute leukemia and bloodstream infections in the era of multiresistance. PloS one. 2018;13(6):e0199531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheich S, Lindner S, Koenig R, Reinheimer C, Wichelhaus TA, Hogardt M, Besier S, Kempf VAJ, Kessel J, Martin H, et al. Clinical impact of colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms on outcome after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2018;124(2):286–296. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheich S, Koenig R, Wilke AC, Lindner S, Reinheimer C, Wichelhaus TA, Hogardt M, Kempf VAJ, Kessel J, Weber S, et al. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia colonization during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associated with impaired survival. PloS one. 2018;13(7):e0201169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cattaneo C, Antoniazzi F, Tumbarello M, Skert C, Borlenghi E, Schieppati F, Cerqui E, Pagani C, Petulla M, Re A, et al. Relapsing bloodstream infections during treatment of acute leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(5):785–790. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanir Basaranoglu S, Ozsurekci Y, Aykac K, Karadag Oncel E, Bicakcigil A, Sancak B, Cengiz AB, Kara A, Ceyhan M. A comparison of blood stream infections with extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and non-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in pediatric patients. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s13052-017-0398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnan M, Gudiol C, Calatayud L, Linares J, Dominguez MA, Batlle M, Ribera JM, Carratala J, Gudiol F. Risk factors for, and clinical relevance of, faecal extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-EC) carriage in neutropenic patients with haematological malignancies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(3):355–360. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornejo-Juarez P, Suarez-Cuenca JA, Volkow-Fernandez P, Silva-Sanchez J, Barrios-Camacho H, Najera-Leon E, Velazquez-Acosta C, Vilar-Compte D. Fecal ESBL Escherichia coli carriage as a risk factor for bacteremia in patients with hematological malignancies. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2772-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karthaus M, Doellmann T, Klimasch T, Krauter J, Heil G, Ganser A. Central venous catheter infections in patients with acute leukemia. Chemotherapy. 2002;48(3):154–157. doi: 10.1159/000064922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theodoro D, Olsen MA, Warren DK, McMullen KM, Asaro P, Henderson A, Tozier M, Fraser V. Emergency Department Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI) Incidence in the Era of Prevention Practices. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(9):1048–1055. doi: 10.1111/acem.12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kugler E, Levi A, Goldberg E, Zaig E, Raanani P, Paul M. The association of central venous catheter placement timing with infection rates in patients with acute leukemia. Leuk Res. 2015;39(3):311–313. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaeger K, Zenz S, Juttner B, Ruschulte H, Kuse E, Heine J, Piepenbrock S, Ganser A, Karthaus M. Reduction of catheter-related infections in neutropenic patients: a prospective controlled randomized trial using a chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine-impregnated central venous catheter. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(4):258–262. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0972-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Legrand M, Max A, Peigne V, Mariotte E, Canet E, Debrumetz A, Lemiale V, Seguin A, Darmon M, Schlemmer B, et al. Survival in neutropenic patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):43–49. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822b50c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, Liu Y, Ma X, Wei L, Chen W, Song L. The incidence and risk factors of peripherally inserted central catheter-related infection among cancer patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:863–871. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S83776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Melot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. Jama. 2001;286(14):1754–1758. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bishop JF, Matthews JP, Young GA, Szer J, Gillett A, Joshua D, Bradstock K, Enno A, Wolf MM, Fox R, et al. A randomized study of high-dose cytarabine in induction in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1996;87(5):1710–1717. doi: 10.1182/blood.V87.5.1710.bloodjournal8751710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larson RA, Dodge RK, Burns CP, Lee EJ, Stone RM, Schulman P, Duggan D, Davey FR, Sobol RE, Frankel SR, et al. A five-drug remission induction regimen with intensive consolidation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cancer and leukemia group B study 8811. Blood. 1995;85(8):2025–2037. doi: 10.1182/blood.V85.8.2025.bloodjournal8582025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(4):530–538. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taplitz RA, Kennedy EB, Bow EJ, Crews J, Gleason C, Hawley DK, Langston AA, Nastoupil LJ, Rajotte M, Rolston K, et al. Outpatient Management of Fever and Neutropenia in Adults Treated for Malignancy: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(14):1443–1453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M, Elting L, Feld R, Gallagher J, Herrstedt J, Rapoport B, Rolston K, et al. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk index: A multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(16):3038–3051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coyne CJ, Le V, Brennan JJ, Castillo EM, Shatsky RA, Ferran K, Brodine S, Vilke GM. Application of the MASCC and CISNE Risk-Stratification Scores to Identify Low-Risk Febrile Neutropenic Patients in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(6):755–764. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee SJ, Kim JH, Han SB, Paik JH, Durey A. Prognostic Factors Predicting Poor Outcome in Cancer Patients with Febrile Neutropenia in the Emergency Department: Usefulness of qSOFA. J Oncol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2183179. 2183179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim M, Ahn S, Kim WY, Sohn CH, Seo DW, Lee YS, Lim KS. Predictive performance of the quick score Sequential Organ Failure Assessment as a screening tool for sepsis, mortality, and intensive care unit admission in patients with febrile neutropenia. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1557–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rolston KV. Challenges in the treatment of infections caused by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in patients with cancer and neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(Suppl 4):S246–252. doi: 10.1086/427331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Collin BA, Leather HL, Wingard JR, Ramphal R. Evolution, incidence, and susceptibility of bacterial bloodstream isolates from 519 bone marrow transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(7):947–953. doi: 10.1086/322604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pittet D, Tarara D, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1994;271(20):1598–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.20.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klastersky J. Current attitudes for therapy of febrile neutropenia with consideration to cost-effectiveness. Curr Opin Oncol. 1998;10(4):284–290. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Viscoli C. The evolution of the empirical management of fever and neutropenia in cancer patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41(Suppl D):65–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_4.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Armstrong D. History of opportunistic infection in the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl 2):S318–321. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.Supplement_2.S318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayer RJ, Davis RB, Schiffer CA, Berg DT, Powell BL, Schulman P, Omura GA, Moore JO, McIntyre OR, Frei E., 3rd Intensive postremission chemotherapy in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer and Leukemia Group B. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(14):896–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lakshmaiah KC, Malabagi AS, Govindbabu, Shetty R, Sinha M, Jayashree RS. Febrile Neutropenia in Hematological Malignancies: Clinical and Microbiological Profile and Outcome in High Risk Patients. J Lab Physicians. 2015;7(2):116–120. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.163126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, Raad II, Rolston KV, Young JA, Wingard JR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e56–93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menzo SL, la Martire G, Ceccarelli G, Venditti M. New Insight on Epidemiology and Management of Bacterial Bloodstream Infection in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2015;7(1):e2015044. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2015.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ricciardi W, Giubbini G, Laurenti P. Surveillance and Control of Antibiotic Resistance in the Mediterranean Region. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016;8(1):e2016036. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2016.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bai AD, Showler A, Burry L, Steinberg M, Ricciuto DR, Fernandes T, Chiu A, Raybardhan S, Science M, Fernando E, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cefazolin versus cloxacillin as definitive antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteraemia: results from a large multicentre cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(5):1539–1546. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hassoun A, Linden PK, Friedman B. Incidence, prevalence, and management of MRSA bacteremia across patient populations-a review of recent developments in MRSA management and treatment. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):211. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mikulska M, Del Bono V, Viscoli C. Bacterial infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21(6):451–458. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Satlin MJ, Walsh TJ. Multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus: Three major threats to hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19(6) doi: 10.1111/tid.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated enteric disease. Annals of internal medicine. 2006;145(10):758–764. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]