Abstract

Zanamivir is a potent and highly selective inhibitor of influenza neuraminidase in which the inhibition of this enzyme prevents the virus from infecting other cells and specifically prevents release of the new virion from the host cell membrane. It is available as an oral powder for inhalation and intravenous formulations. The current population pharmacokinetic model based on data from eight studies of subjects treated with the intravenous formulation (125 healthy adults and 533 hospitalized adult and pediatric subjects with suspected or confirmed influenza) suggested a decreased zanamivir clearance in pediatric and renal impairment adult subjects. It also indicates that b.i.d. dosing is necessary to keep the exposure in influenza infected subjects above the 90% inhibitory concentration values of recently circulating viruses over the dosing interval. In the exposure‐response analysis (phases II and III studies), no apparent relationship was found between zanamivir exposure and clinically relevant pharmacodynamic end points.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ Zanamivir is a potent and highly selective inhibitor of influenza neuraminidase preventing the virus from infecting other cells. Following i.v. administration, its disposition is biphasic and it is predominantly renally eliminated. In clinical trials, dosing of i.v. zanamivir was based on renal function in adults and renal function and weight in pediatrics.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ This study addressed the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationship of zanamivir following i.v. dosing in hospitalized pediatric and adults with influenza and those with and without renal impairment.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

☑ This is the first large‐scale analysis of PK and PD data of zanamivir in pediatric and adult subjects with and without renal impairment. The results of this analysis were used to support pediatric dosing recommendations, which were based on body weight, age, and renal function.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

☑ This study used state‐of‐the‐art modeling techniques to confirm the efficacious dosing regimens in hospitalized adults and pediatric subjects with influenza.

Influenza remains an important public health priority, with seasonal outbreaks and pandemics causing significant morbidity and mortality. The severity of influenza is determined by the antigenic composition of the virus and the extent of pre‐existing immunity in the population.1 Immunity to influenza results from the development of neutralizing antibodies to the viral surface proteins, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase (NA).2 When the antigenicity of these proteins changes, in a process called antigenic drift, the influenza virus can evade the immune response and establish infection.1 Pandemic influenza is considered by many experts to be the most significant global public health emergency caused by a naturally occurring pathogen.

Zanamivir is a potent and highly selective inhibitor of influenza NA, preventing the virus from infecting other cells. Zanamivir powder for inhalation (Relenza, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) is approved for the treatment and prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza.3 The emergence of virus isolates resistant to influenza antiviral agents continues to be a potential concern.4 Resistance to zanamivir is rare and is generally observed in immunocompromised subjects. Zanamivir is the only approved influenza antiviral for which high‐level resistance has rarely been observed to develop in immunocompetent subjects with acute infection. Resistance to zanamivir has not been observed in >14,000 subjects participating in treatment and prophylaxis clinical studies evaluating the inhaled formulation. 5, 6 Resistance to zanamivir in studies of i.v. zanamivir identified three subjects with resistance associated NA substitutions; E119D (H1N1pdm09) isolated from an immunocompromised adult, E119G (H1N1pdm09) isolated from an immunocompetent infant, and T325I (H3N2) isolated from an immunocompetent subject on day 2. To date, the most common H1N1 resistance substitution H275Y confers resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir but retains susceptibility to zanamivir.7, 8

An unmet medical need exists for alternative formulations to treat critically ill subjects with severe influenza illness for whom currently available oral and oral inhaled treatments are not suitable. No parenteral influenza antiviral agents are approved for treatment of hospitalized patients with complicated influenza. Intravenous peramivir has recently been approved in the United States, the European Union, and a limited number of other countries as a single infusion for treatment of uncomplicated influenza. An i.v. formulation of zanamivir has been developed for treatment of hospitalized patients with influenza infection for whom an inhaled or oral formulation is not suitable.

Following i.v. administration in healthy adults, zanamivir disposition was reported as biphasic.9 Zanamivir is predominantly renally eliminated as unchanged drug, with clearance (CL) consistent with glomerular filtration rate (~ 125 mL/minute). Zanamivir volume of distribution is consistent with extracellular fluid volume (~ 19 L), and it has low protein binding (< 10%). A two‐compartment pharmacokinetic (PK) model was previously used to characterize zanamivir PKs following i.v. administration in healthy Thai adults.10

The current population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) and exposure‐response population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PopPK/PD) analyses of zanamivir following i.v. administration were performed, including data from the following populations: healthy subjects and hospitalized pediatric, adolescent, and adults with influenza, including those with various degrees of renal impairment. Subjects with renal impairment received an initial i.v. zanamivir dose followed by an adjusted b.i.d. maintenance dose according to their effective renal function for 5–10 days (Table S1 ). The model development was performed based on pooled data from six phase I healthy volunteer studies, as well as one phase II (NAI113678) and one phase III (NAI114373) study. Both phase II and III studies involved hospitalized subjects with suspected or confirmed influenza. The objectives of the analysis were: (i) to establish and evaluate a PopPK model with significant covariates that describe the PKs of i.v. zanamivir in adult and pediatric subjects; and (ii) to assess the relationship among model‐predicted individual zanamivir exposure parameters and pharmacodynamic (PD) responses and provide confirmation on dosing regimens for i.v. zanamivir.

Methods

The current analysis was conducted on subjects receiving zanamivir by i.v. infusion and who were participants in six healthy adult subjects’ studies and two studies in hospitalized subjects with influenza infection that consisted of adult, adolescent, and pediatric subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or legally acceptable representative. All these studies were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees and with the Declaration of Helsinki or comparable ethical standards.

Study design and study population

The dosing, PK sampling, and http://www.clinicaltrial.gov IDs of all the studies included are summarized in Table S2 .

Bioanalysis

Human serum samples were analyzed for zanamivir using a validated analytical method based on protein precipitation, followed by high‐performance liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry analysis. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for zanamivir ranged from 0.02−10 ng/mL across different studies. The applicable analytical methods met all predefined method acceptance criteria.

PopPK analysis

PopPK analysis was conducted via nonlinear mixed‐effects modeling with NONMEM, version 7.2 (ICON Development Solutions).11 The first‐order conditional estimation with interaction method in NONMEM was used. Data manipulation, graphical and statistical summaries were performed using R version 3.2.3 ( http://www.r-project.org/).

For the PopPK analysis, 5,273 serum samples from 658 subjects, including 19% healthy and 81% influenza subjects who received i.v. infusion of zanamivir at single doses of 100–1,200 mg, and 300–600 mg repeat b.i.d. dosing were combined from the eight clinical studies of various phases (I–III). The basic distributions of covariates and the number of subjects receiving i.v. zanamivir by the study are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics based on data for final model

| Study |

Phase I study 1 NAI1009 (N = 12) |

Phase I study 2 NAI 108127 (N = 16) |

Phase I study 3 NAI 112977 (N = 16) |

Phase I study 4 NAI 114346 (N = 39) |

Phase I study 5 NAI 115070 (N = 18) |

Phase I study 6 NAI 117104 (N = 24) |

Phase II study NAI 113678 (N = 180) |

Phase III study NAI 114373 (N = 353) |

Total (N = 658) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsa | 22.1 (19.66, 38.7) | 69 (40, 77) | 26 (20, 45) | 28 (19, 52) | 30 (22, 39) | 24.5 (19, 32) | 39.5 (0.6, 94) | 57 (15, 101) | 46 (0.6, 101) |

| Body weight, kga | 78.9 (63.5, 88.9) | 85.9 (70.7, 104.3) | 62.1 (50.0, 70.9) | 74.0 (52.7, 110.0) | 65.3 (56.4, 77.7) | 58.3 (50.0, 76.0) | 67.0 (7.1, 140.6) | 46.6 (38.0, 188.0) | 72.0 (7.1, 188.0) |

| Height, cma | 186 (175, 195) | 170 (156, 198) | 168 (158, 178) | 169 (158, 190) | 172.5 (165, 182) | 165 (150.4, 178) | 165 (62, 196) | 168 (142, 196) | 168 (62, 198) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 a | 22.7 (19.3, 26.5) | 27.7 (22.3, 34.3) | 22.0 (19.0, 23.5) | 26.8 (19.4, 30.7) | 22.1 (19.1, 24.7) | 22.1 (19.6, 24.0) | 24.2 (12.1, 61.9) | 26.6 (15.2, 65.8) | 25.0 (12.1, 65.8) |

| Body surface area, m2 a | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.5, 1.9) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.4) | 1.8 (1.6, 2.0) | 1.6 (1.5, 1.9) | 1.8 (0.4, 2.9) | 1.9 (1.2, 3.2) | 1.8 (0.4, 3.2) |

| Serum creatinine, μMa | 63.0 (55.0, 94.0) | 132.6 (70.7, 380.1) | 84.0 (61.9, 106.1) | 78.7 (46.9, 99.0) | 69.8 (53.0, 87.5) | 67.5 (49.0, 101.0) | 61.9 (17.7, 685.0) | 74.2 (24.2, 357.6) | 72.5 (17.7, 685.0) |

| CrCL, mL/minutea | 160.4 (121.8, 238.4) | 48.7 (12.1, 127.0) | 101.6 (69.0, 127.6) | 125.0 (85.1, 191.4) | 133.5 (105.8, 190.9) | 109.6 (96.1, 148.6) | 79. 6 (12.4, 261.2) | 83.6 (13.1, 274.9) | 91.8 (12.1, 274.9) |

| Extracellular fluid volume, La | 16.0 (13.3, 17.8) | 15.6 (13.2, 19.6) | 12.6 (10.6, 14.3) | 14.2 (11.0, 20.1) | 13.3 (11.9, 15.3) | 12.1 (10.2, 15.1) | 13.2 (1.6, 22.7) | 14.5 (8.5, 26.1) | 14.1 (1.56, 26.1) |

| N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | N (%b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 2 (0.3) | 14 (2) | 0 (0) | 12 (2) | 72 (11) | 146 (22) | 254 (39) |

| Male | 12 (2) | 8 (1) | 14 (2) | 25 (4) | 18 (3) | 12 (2) | 108 (16) | 207 (31) | 404 (61) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 16 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (3) | 33 (5) | 68 (10) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 23 (3) | 18 (3) | 24 (4) | 161 (24) | 308 (47) | 566 (86) |

| Unknown | 12 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (2) | 24 (4) |

| Race | |||||||||

| African American/African | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (3) | 15 (2) | 48 (7) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.8) | 8 (1) |

| South/Central Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.6) | 6 (0.9) |

| East Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 24 (4) | 4 (0.6) | 24 (4) | 53 (8) |

| Japanese | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 21 (3) |

| South East Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 27 (4) |

| Native American or Other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) |

| White‐Arabic/North African Heritage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 7 (2) | 15 (2) |

| White/European | 19 (3) | 13 (2) | 0 (0) | 23 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 132 (20) | 292 (44) | 472 (72) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) |

| Influenza type | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 180 (27) | 353 (54) | 533 (81) |

| Influenza virus type A, H1N1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 101 (15) | 110 (17) | 211 (32) |

| Influenza virus type A, H3N2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 34 (5) | 128 (19) | 162 (25) |

| Influenza virus type A, unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 17 (3) | 4 (0.6) | 21 (3) |

| Influenza virus type B | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (3) | 37 (6) | 82 (12) |

| Coinfection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Influenza virus type unknown or negative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (1) | 68 (10) | 74 (11) |

| Renal impairmentc | |||||||||

| Normal renal function (CrCL ≥ 80 mL/minute) | 12 (2) | 3 (0.5) | 15 (2) | 39 (6) | 18 (3) | 24 (4) | 88 (13) | 192 (29) | 391 (59) |

| Mild (CrCL ≥ 50 and < 80 mL/minute) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 38 (6) | 87 (13) | 131 (20) |

| Moderate (CrCL ≥ 30 and < 50 mL/minute) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 29 (4) | 43 (7) | 75 (11) |

| Severe (CrCL ≥ 15 and < 30 mL/minute) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (3) | 25 (4) | 50 (8) |

| End‐stage (CrCL < 15 mL/minute) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 6 (1) | 11 (2) |

| RRT | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (2) | 5 (1) | 16 (2.4) |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 2 (0.3) | 10 (1.5) |

CrCL, creatinine clearance; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Continuous variables are presented as median (range).

Percentages were calculated based on combined population from eight studies.

Categorization of renal impairment was based on zanamivir i.v. dosing.

The model goodness‐of‐fit was evaluated by a variety of metrics and plots, including relative standard errors of the parameter estimates, shrinkage estimates, successful minimization, condition number, objective function value, and standard goodness‐of‐fit plots. To account for large variations resulting from multiple zanamivir dose levels and in populations,12 prediction‐corrected visual predictive check (pcVPC) was used in the model validation step. The ability of the model to identify strong covariate relationships was tested by stratifying the predictive check procedures by the covariates of interest. Concentrations below the LLOQ (0.01 μg/mL) were imputed at the LLOQ value. A nonparametric bootstrap analysis was conducted to provide the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the final model.

Following the development of the base PK model, the covariate analysis was conducted using the “full model” approach, where all covariate‐parameter relationships of interest were entered in the model simultaneously and examined by comparing predicted effect range with predefined ranges (i.e., 0.8 to 1.2 for categorical covariates and −0.2 to 0.2 for continuous covariates). The selection of covariates of interest, including the subject's baseline demographics, influenza virus infection status, and treatment type (ECMO, renal replacement therapy (RRT)), was based primarily on clinical relevance and mechanistic plausibility.13 For subjects who were not on RRT, their corresponding creatinine clearance (CrCL) were derived based on the Cockcroft‐Gault equation,14 for adults or based on the Schwartz equation15 for infants and children under 13 years of age.

The final model was used to compute, through empirical Bayes estimation, the individual estimates of PK parameters and derived descriptive PK parameters that include area under the concentration‐time curve from zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) from initial dose, area under the concentration‐time profiles (AUC0–τ), and trough concentrations (Cτ) from maintenance dosing, and peak plasma concentration (Cmax), time of maximum plasma concentration (Tmax), and terminal half‐life (t1/2) from both initial and maintenance doses. Predicted exposure parameters of zanamivir in pediatric subjects were compared with adults to support the pediatric dosing regimen developed prior to the PopPK modeling. A total of 1,000 simulations following 300 and 600 mg under both q.d. and b.i.d. regimens were conducted based on the final model to evaluate the influence of age and renal function on exposure, as well as to estimate the percentage of subjects with zanamivir Cτ above the in vitro 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90; 0.00173 μg/mL for influenza, A/H1N1 and 0.00783 μg/mL for influenza virus type B) values for the influenza viruses.

PK/PD analyses

Efficacy data for 536 patients from phase II and phase III studies were used in PopPK/PD analyses. Subjects included were hospitalized patients with suspected or confirmed influenza who had a baseline virologic measure and at least one post hoc exposure measure. Three of the 356 influenza infected subjects had post hoc exposures based on the average PopPK parameters with similar demographic characteristics and dosing regimen. The efficacy end points analyzed in the final analysis were time to clinical response, time to sustained virologic improvement, time to no detectable quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) from nasopharyngeal swabs, time to absence of viral culture from nasopharyngeal swabs, along with daily viral load change as measured by qRT‐PCR, and viral culture from nasopharyngeal samples.

The PopPK/PD analysis was conducted in a sequential manner with the model‐predicted individual post hoc exposure measures of AUC0–τ, Cmax, and Cτ being estimated for all dosing intervals through PopPK analysis and then an average overall exposure for each patient was sequentially explored in the PD analysis.

A multivariate Cox‐Proportional model was used to assess the significance of clinically relevant demographic variables, along with post hoc exposure measures from the PopPK model. Demographic differences were investigated within multivariate modeling to help eliminate any confounding differences in the exposure groups. The selection of variables was based on their clinical relevance or if they were identified in the previous analysis as being a relevant covariate in the individual studies.

Time to event analyses

Time to event analyses were explored graphically using Kaplan–Meier curves and modeled using multivariate Cox‐Proportional model to assess the significance of clinically relevant demographic variables, along with post hoc exposure measures from the PopPK model. Subjects who did not have an event were censored at last observation day or death. The time‐to‐event modeling was performed in R using the Survival Package.16

A sequential analysis was performed to identify an initial model that best explained differences in survival times of the efficacy end points using the prespecified covariates. Covariates were investigated with univariate Cox‐Proportional hazard model. A stepwise selection method in which variables were entered into and removed from the model was then performed on all risk factors in the multivariate Cox‐Proportional model. The model selection at each iteration was achieved by selecting the model with the lowest significant Akaike information criterion (AIC). Each post hoc measure entered the initial model individually in both linear and log‐transformed fashion. Only post hoc exposure measures that reduced the AIC were retained. If the addition of an exposure variable improved the AIC, several criteria were used to assess the impact of the exposure measure. The hazard ratio (HR) was assessed for statistical significance by evaluating the P value, along with evaluating the change in pseudo‐R 2 and AIC values, with minimal changes indicating less relevance in the model. To determine the HR between the 90th percentile and 10th percentile of the added exposure measure, the equation below was used.

The calculated HR was then transformed into the probability of the higher exposure individual (90%) responding first using the equation below.17

Finally, the model with an exposure variable was assessed with a backward elimination method using the likelihood ratio test, along with assessing individual HR for each covariate when included or removed, and only retaining a covariate if it was significant at P < 0.01 and the likelihood ratio test was significantly different between the two models.

Virology exposure‐response analysis

Daily change from baseline of the viral load measured via qRT‐PCR and quantitative virus cultures were graphically explored vs. cumulative daily average post hoc PopPK parameters, to examine for a correlation over days 1–5.

Results

Study population demographics

Overall, 5,273 observations from 658 subjects were included in the modeling data set. Among these observations, 2,516 (48%) were from hospitalized subjects (n = 533) with suspected or confirmed influenza, with 289 (5.5%) observations from pediatric or adolescent subjects (n = 58). A small portion of the population used to build the PopPK model were healthy subjects (19%). Patients with influenza (74%) included in this analysis were predominantly affected by influenza virus type A (H1N1 and H3N2), with only 12% infected by type B or coinfection of both types A and B. Within the patient population, 57% were renally impaired and 11% were pediatric (< 18 years). There were 16 subjects who underwent RRT and 10 subjects had ECMO in the phase II and phase III studies. Further characteristics are recorded in Table 1, with additional demographics used in PD analysis recorded in Table S3 .

PopPK analysis

The optimal structural model for zanamivir PKs consisted of a two‐compartment model with interindividual variability on clearance and central compartment volume with combined residual error model (Table 2). Zanamivir CL was predominantly driven by CrCL, which was best characterized by a stepwise linear equation with inflection point estimated at 97 mL/minute. The effect was fixed to 1 for CrCL above 97 mL/minute and described by 1 + (CrCL‐97)*0.00923 for CrCL below 97 mL/minute. Besides the stepwise linear model, various forms of maximum effect (Emax) models and categorical models (based on renal impairment categories) were also explored but resulted in either higher AIC values or difficulty with convergence. Similar pcVPC plots were observed for these models.

Table 2.

Population PK parameter estimates of base, full, and final PK models for zanamivir

| Parameter (units) | Base model | Full model | Final model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parameter estimate (% RSE) |

Parameter estimate (% RSE) |

95% CIc |

Parameter estimate (% RSE) |

Bootstrapa median (95% CI) |

|

| CL, L/hour | 4.12 (3) | 6.81 (2) | 6.56, 7.05 | 6.82 (2) | 6.83 (6.60, 7.0909) |

| V1, L | 12.9 (2) | 12.3 (2) | 11.8, 12.8 | 12.3 (2) | 12.3 (11.88, 12.8) |

| Q, L/hour | 2.59 (12) | 4.82 (8) | 4.06, 5.58 | 4.82 (8) | 4.83 (4.20, 5.5858) |

| V2, L | 4.32 (7) | 6.52 (4) | 5.99, 7.05 | 6.52 (4) | 6.54 (6.0606, 7.0404) |

| Covariate effects | |||||

| CL ~ CrCL (inflection point) (mL/minute) | – | 97.0 (2) | 93.1, 101 | 97.0 (2) | 97.1 (87.55, 111) |

| CL ~ CrCL (slope) (minute/mL) | – | 0.00923 (8) | 0.00786, 0.0106 | 0.00929 (7) | 0.00923 (0.00754, 0.0110) |

| CL ~ FLU | – | 0.763 (4) | 0.701, 0.825 | 0.756 (4) | 0.760 (0.707, 0.814) |

| CL ~ RRT | – | 0.900 (14) | 0.645, 1.155 | – | – |

| CL ~ ECMO | – | 0.704 (21) | 0.416, 0.992 | – | – |

| V1/V2 ~ WT | – | 0.711 (4) | 0.652, 0.770 | 0.711 (4) | 0.712 (0.649, 0.769) |

| V1/V2 ~ Study (NAI114346) | – | 0.729 (2) | 0.699, 0.759 | 0.729 (2) | 0.728 (0.700, 0.760) |

| Q ~ WT | – | 0.658 (9) | 0.538, 0.778 | 0.658 (9) | 0.659 (0.514, 0.768) |

| IIV (CL) ~ FLU | – | 3.07 (11) | 2.41, 3.73 | 3.10 (11) | 3.12 (2.5454, 3.8181) |

| IIV | |||||

| IIVCL, CV% (% η‐shrinkage) | 69.4 (5) | 18.8 (6) | 18.7 (6) | 18.5 (15.4, 22.7) | |

| IIVV1, CV% (% η‐shrinkage) | 50.9 (9) | 34.8 (17) | 34.8 (17) | 34.8 (30.5, 40.7) | |

| Residual variability | |||||

| Proportional error, CV% (% RSE) | 27.2 (4) | 26.2 (4) | 26.2 (4) | 26.2 (24.9, 27.5) | |

| Additive error (μg/mL), SD (% RSE) | 0.0268 (5) | 0.0269 (5) | 0.0269 (5) | 0.0269 (0.0243, 0.0294) | |

CI, confidence interval; CL, clearance; CrCL, creatinine clearance; CV%, coefficient of variation percentage; IIV, interindividual variability; PK, pharmacokinetic; Q, intercompartmental clearance; RRT, renal replacement therapy; RSE, relative standard error; WT, weight.

The 95% CI were calculated parameters (mean, SE) from outputs covariance step in NONMEM.

From 1,187 bootstrap simulations with successful minimization out of 1,500 simulations. The 95% CI was calculated from 2.5th–97.5th percentile. Eta‐shrinkage was not reported for the bootstrap and CIs are displayed in the parenthesis for both interindividual and residual variabilities.

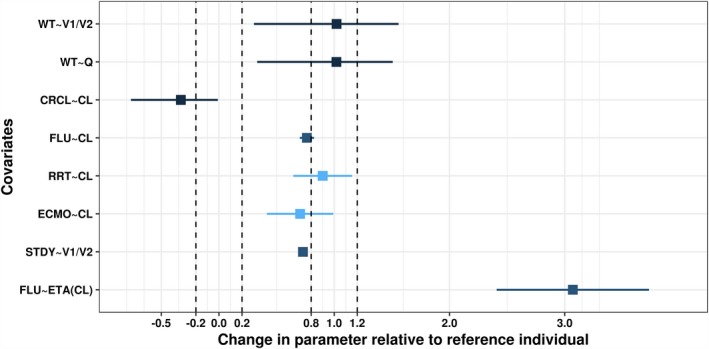

Besides CrCL effect on CL, the full model covariate analysis also included weight effect on central (V1) and peripheral (V2) volume of distribution and intercompartmental clearance, effects of being infected by influenza, and being on RRT or ECMO on CL and study effect on V1 and V2 (Table 2). During evaluation of their effect ranges, effects of ECMO and RRT on CL were dropped from the full model as their corresponding effect ranges overlapped with null range representing lack of clinical relevance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forest plot for the effects of covariates on pharmacokinetic parameters relative to reference individual. Reference individual is defined as healthy subject with body weight (WT) of 70 kg and estimated creatinine clearance (CrCL) above 97 mL/minute. ETA, inter‐individual variability; RRT, renal replacement therapy; RSE, relative standard error; STDY, study.

Based on the final PopPK model (Table 2), zanamivir clearance for a typical healthy subject of standard weight (70 kg) was estimated to be 6.82 L/hour (113.67 mL/minute), which decreased by 24% to 5.16 L/hour (85.9 mL/minute) if these subjects were infected with influenza. Within the infected population, clearance is expected to further reduce 26–54% if a subject had mild renal impairment (CrCL 50 to < 80 mL/minute), 54–72% in moderate impairment (CrCL 30 to < 50 mL/minute), 72–86% in severe impairment (CrCL 15 to < 30 mL/minute), and >86% for end‐stage renal disease (CrCL < 15 mL/minute).

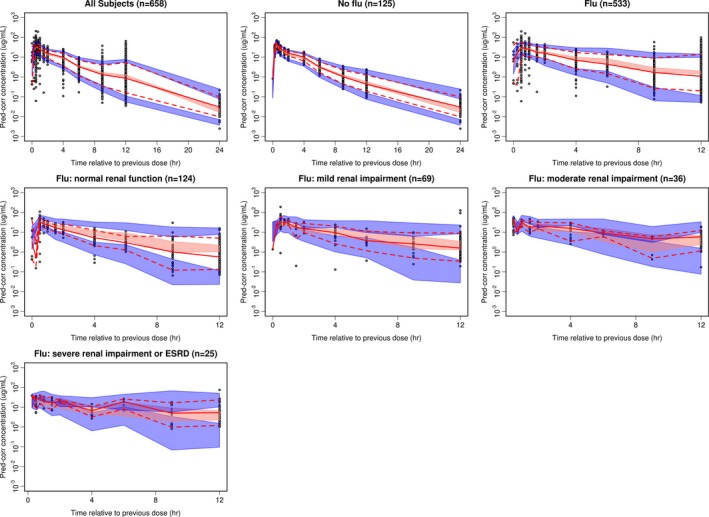

The pcVPC plots (Figure 2) demonstrate that the final PopPK model provided a good description of the time course and variability of zanamivir serum concentrations in both healthy and subjects with influenza regardless of renal function.

Figure 2.

Prediction‐corrected visual predictive check plots for final model with no stratification and stratification on patient type and renal function. In all these plots, black circles are observations; red solid and dash lines represent the median (solid line), 5th and 95th percentiles (dash lines) of the observations; the shaded region are the 95% confidence intervals (2.5–97.5th percentiles) around the median (pink), 5th and 95th percentiles (blue) based on model simulations. Y axis corresponds to plasma concentrations. ESRD, end‐stage renal disease.

The model‐predicted individual estimates for PK parameters in subjects with influenza who were not on ECMO or RRT following the initial zanamivir dose and maintenance doses are summarized in Tables S4 and S5 , respectively. The number of subjects in some renal impairment and age categories was too small to determine any meaningful trends. However, for subjects with normal renal function, Cmax, AUC0–∞, AUC0–τ, and t1/2 were consistent across different age cohort for both dose events. Clearance decreased in a linear fashion with a decrease in renal function (i.e., CrCL). The half‐life was predicted to almost triple to 8.93 hours in the end‐stage renal impaired adult subjects as compared with adults with normal renal function (t1/2 = 3.2 hours). The steady‐state Cτ decreased in the pediatric population, mainly because of the lower doses administered, but they are still above the in vitro IC90 values for both subtypes (A and B) of the influenza viruses. The maximum in vitro IC90 value for influenza virus A/H1N1 (5.31 nM) and influenza virus B (23.55 nM) was used for the comparison. It is evident that the exposures from pediatric and renally impaired patients were within the range of adults with normal renal function.

Simulations of zanamivir exposures

The steady‐state concentration‐time profiles from 1,000 simulations following 300 and 600 mg b.i.d. are summarized in Supplementary Tables S6 and S7 , respectively. Overall, as renal function decreases and patients’ age gets younger, the exposure of zanamivir increases, suggesting the need for dose adjustment.

The percentage of subjects who maintain serum zanamivir concentrations over the entire dosing interval above the in vitro IC90 values for influenza A and influenza B viruses at steady‐state following 300 mg and 600 mg b.i.d. i.v. zanamivir were also estimated and shown in Table 3 after accounting for protein binding (< 10%, 10% was used). It is predicted that 96.4% and 95.5% of all infected subjects will be above the IC90 values for influenza subtypes A and B, respectively, at steady‐state when administered 300 mg b.i.d. The same percentages only slightly increased to 97.7% and 97.0% for influenza subtypes A and B, respectively, when 600 mg b.i.d. is administered. As a contrast, a q.d. regimen of 600 mg only resulted in ~ 82.9% and 78.8% of subjects above IC90 values for influenza subtypes A and B, respectively, for the Cτ at steady‐state, whereas 300 mg q.d. is even lower (75–79%).

Table 3.

| Dose regimen | % of Subjects with Cτa > cutoff values for influenza virus type Ab | % of Subjects with Cτa > cutoff values for influenza virus type Bb |

|---|---|---|

| 300 mg q.d. | 79.4 (76.2, 82.9) | 74.7 (70.9, 78.2) |

| 300 mg b.i.d. | 96.4 (94.7, 97.9) | 95.5 (93.6, 97.0) |

| 600 mg q.d. | 82.9 (79.5, 85.7) | 78.8 (75.6, 82.2) |

| 600 mg b.i.d. | 97.7 (96.4, 98.9) | 97.0 (95.7, 98.3) |

Cτ, trough concentration; IC90, 90% inhibitory concentration.

Concentrations were scaled by taking consideration of in vitro protein binding (< 10%, 10% was used).

Estimates are presented as median and 95% CI around the median based on the 1,000 simulations.

The maximum of in vitro IC90 values for influenza A/H1N1 (0.00176 μg/mL) and influenza A/H3N2 (0.00171 μg/mL) were used in the simulation. The in vitro IC90 value for influenza B was 0.00783 μg/mL.

PK‐PD analyses

Time‐to‐event analyses

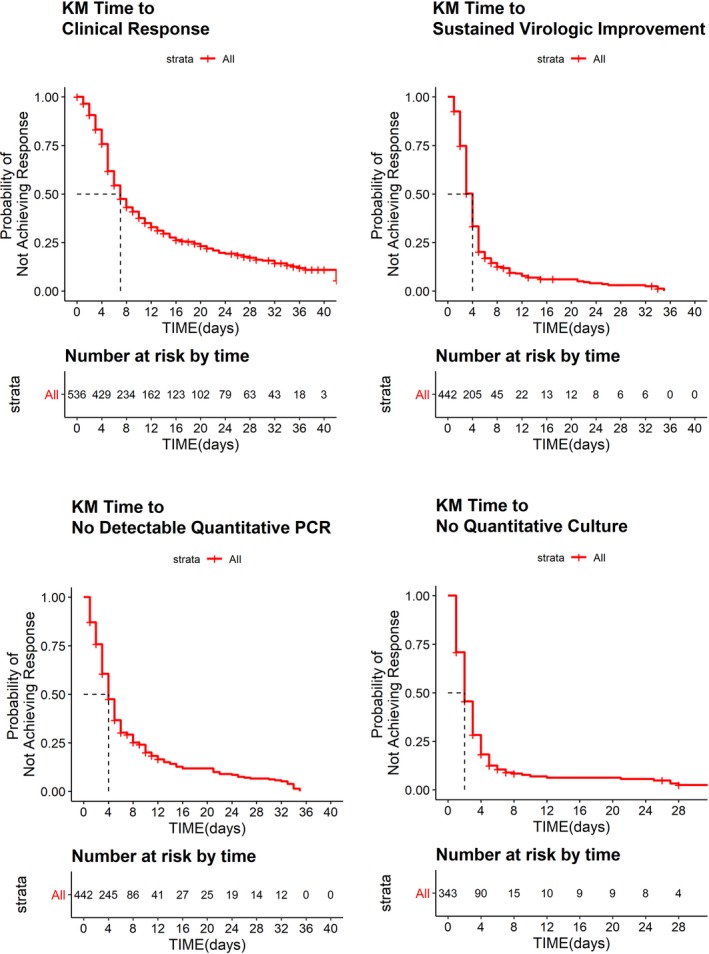

Kaplan–Meier curves for the four time‐to‐event efficacy end points, one clinical, and three virology, are shown in Figure 3. A total of 536 individuals from the phase II and phase III studies who were suspected or diagnosed to have influenza had the efficacy end point of time to clinical response along with post hoc exposure estimates, whereas only 442 subjects had the end points of time to sustained virologic improvement and time to no quantitative PCR, and only 343 subjects had the end point of time to no cultivable virus. As expected, the median time to clinical response followed the median time to virologic improvement by a few days. Correlation plots (not shown) between clinical response time and the other virologic response times did not show a strong correlation (Spearman correlation coefficient < 0.25).

Figure 3.

Raw Kaplan–Meier (KM) curves for time‐to‐event analyses. Red lines mark median time to response for each end point. PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Kaplan–Meier curves (not shown) for time to response for each of the four efficacy end points were stratified by exposure quartile of each of the post hoc exposure measures (Cmax, Cτ, and AUC0–τ). This graphical analysis revealed exposure had no effect on time to virologic response as measured by quantitative virus culture. However, to further investigate the effect of exposure on the remaining three efficacy end points, a Cox regression analysis was conducted to account for any demographic differences that occurred within the exposure quartiles. None of the exposure measures were found to significantly affect the response rate for these efficacy end points.

Time to clinical response

An initial multivariate Cox‐Proportional model identified the most relevant risk factors that impacted the time to clinical response to be: in the intensive care unit (ICU) or mechanically ventilated patient with or without ECMO or RRT, older age, start of the therapy with i.v. zanamivir in later stages of the infection, and/or using prior systemic anti‐infectives/anti‐influenza therapy. Additionally, the use of immunomodulating therapy and infection with the H3N2 influenza virus were incorporated in this model. Cmax was the only exposure variable that decreased the AIC when compared with the base model. However, the HR for Cmax variable was considered nonsignificant (P < 0.01) and clinically not relevant when comparing the HR of individuals in the highest quartile of exposure with the individuals in the lowest quartile of exposure. A backward elimination process was carried out on the model with the inclusion of the Cmax exposure and determined that the most impactful variable on time to clinical response when accounting for other variables was if the subject was in the ICU or mechanically ventilated or was an ICU patient on ECMO or RRT (Table S8 ). The rate of a positive clinical response of a subject in the ICU/mechanically ventilated was ~ 4 times smaller than that of a subject who was not in an ICU and/or on mechanical ventilation.

Time to sustained virologic improvement and to no detectable viral load

The initial model used to explore the impact of the exposures measures on the time to sustained virologic improvement contained: ICU/mechanically ventilated subjects, ethnicity, and prior use of systemic anti‐infectives/antivirals. Inclusion of exposure measures did not improve the model fit when added and the HR were all found to be insignificant. A similar analysis was performed on time to no detectable viral load as measured by qRT‐PCR and the HR for post hoc exposures measures were found to be insignificant in multivariate model.

Virology exposure‐response analysis

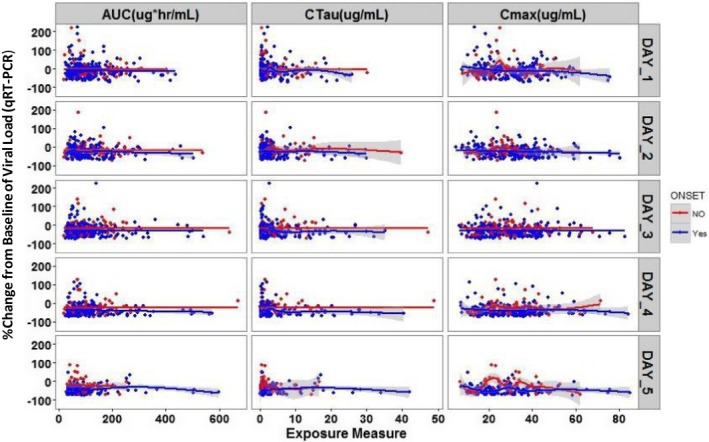

As final examination of exposure‐response relationship for zanamivir, plots were created to explore the average daily exposure of zanamivir and the change in viral load from baseline as determined by qRT‐PCR and viral culture in a subset of the population. Individuals were stratified by those who started zanamivir within 4 days of symptom onset (blue) and those who started treatment > 4 days after symptom onset (red; Figure 4 and Figure S1 ). Figure 4 illustrates that across all 5 days there seems to be no significant correlation between exposure variables and change in viral load as determined by qRT‐PCR in either group. A second conclusion from the graph is that by day 5 (relative baseline day), most individuals who had started treatment within 4 days of onset of symptoms have reduced their viral load below their baseline value, whereas there are still a few individuals who started treatment > 4 days after symptom onset with values greater than their baseline value. A similar exploration was performed with viral culture data for day 1 and day 2 following the start of therapy due to most individuals having no measurable viral culture beyond day 2. Figure S1 shows that there was no strong relationship between drug exposure and percent change in viral load from baseline regardless if therapy was started early or late. These graphs also illustrate that 2 days after starting treatment almost all individuals had decreased their viral culture level below their baseline level.

Figure 4.

Change from baseline in viral load (quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR)) by average exposure and by day. In all these plots, blue dots are observations and blue line is local regression smoothing line (95% confidence interval (CI) shaded region) for individuals who had symptom onset within 4 days before start of zanamivir treatment; red dots are observations and red line is local regression smoothing line (95% CI shaded region) for individuals who had symptom onset > 4 days before the start of zanamivir treatment. Time on x‐axis is day relative to baseline measure. Unit for qRT‐PCR is copies/mL. AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, peak plasma concentration; Ctau, trough concentration.

Overall, these analyses indicate that there is no consistent correlation between the drug concentration/exposure achieved and reduction in viral load.

Discussion

This is the first formal analysis to investigate the PopPK of i.v. zanamivir and corresponding response in subjects infected by influenza virus (i.e., PopPK/PD). A PopPK model that describes the single‐dose and repeat‐dose PKs of i.v. zanamivir in adult and pediatric subjects was developed and used to identify covariates that may influence the PKs of zanamivir. The model‐predicted exposures of zanamivir were compared with noncompartmental analysis results and simulated exposures were used later to assess the relationship of zanamivir exposure measures with virologic and clinical response.

Zanamivir PK was reasonably described by a two‐compartment model with i.v. infusion and first‐order elimination. Compared with heathy adults, clearance of zanamivir decreased by 24% in subjects infected with influenza, with even more decreases renally impaired influenza‐infected patients. The total volume of distribution at steady‐state = V1 + V2 for zanamivir was estimated to be 18.8 L for a typical adult subject with body weight of 70 kg, which further confirmed the understanding based on the outcome of earlier studies that the zanamivir volume of distribution is consistent with extracellular fluid volume (~ 19 L). There was an overall agreement when predicted individual estimates of PK parameters were compared with those derived from noncompartmental analysis based on study NAI113678 (phase II) following both initial and maintenance dose of zanamivir.18 The small number of subjects in younger cohorts (under 2 years) and some categories of renal impairment (severe and end‐stage) posed a challenge to interpret the results. However, it is quite evident that the exposures in pediatrics were within the predicted range of adults regardless of the renal function. Similar results were observed for the oral inhalation formulation of zanamivir where the PK in children was similar to adults.19, 20 Moreover, i.v. zanamivir showed similar PK, safety, and efficacy results in children compared with adults.21 As zanamivir is predominantly cleared renally as unchanged drug, impaired renal function is expected to affect zanamivir's clearance. PopPK indicated that its half‐life increases two to threefold for severe and end‐stage renal disease. A study effect on the volumes of distribution (V1 and V2) for study NAI114346 (phase I study 4) does not affect the simulation or post hoc summary because subjects from study NAI114346 were all healthy volunteers, whereas the simulations were conducted on the infected subject population. Similarly, the scaling factor added to account for the difference in intersubject variability between healthy and infected subjects does not affect the prediction of zanamivir exposure in influenza‐infected subjects. The effects for treatments ECMO and RRT were dropped during full model covariate analysis as their corresponding 95% CI had significant overlap with the null value range. This is not surprising as the number of the subjects on these two treatments was quite small (collectively < 4% of the total population) and may have resulted in uncertainty to accurately characterize their effects on zanamivir PK, if any. The decision to test them initially despite small sample size was due to the concern around potential dose adjustment in influenza‐infected subjects undergoing these supportive measures.

The simulations based on the final model and study population characteristics following 300 and 600 mg b.i.d. provided further confirmation that the dose adjustment was necessary for pediatric subjects and for those with renal impairment. The post hoc estimates for PK parameters in infected subjects who were not on ECMO or RRT following initial zanamivir dose and maintenance dose are summarized in Tables S4 and S5 , respectively. The number of subjects in some renal impairment and age category is too small to determine any meaningful trends. However, for subjects with normal renal function, Cmax, AUC0–∞, AUC0–τ, and t1/2 were consistent across different age cohort for both dose events.

Across the phase II and phase III clinical studies in hospitalized subjects with influenza, it was found that treatment in the ICU or use of mechanical ventilation lengthens the time to achieve criteria for a positive clinical outcome, reflected by a longer median time of response for the entire analysis. As expected, time for virologic response was shorter than the composite clinical response definition used in these studies. Median time to virologic response was within 4 days from treatment start day.

None of the exposure measures was found to significantly affect the response rate for either the clinical end point or the virologic end point. These results were not surprising when viewed in the context that PopPK post hoc estimates for Cτ were all above IC90 of zanamivir for influenza viruses with further confirmation coming from the virologic change from baseline plots showing no correlation to the daily zanamivir exposures. This would suggest that serum zanamivir concentration do not translate to the concentration of drug at the effect site. The i.v. zanamivir at a dose of 600 mg b.i.d. has been shown to distribute to the respiratory mucosa and is protective against infection and illness following experimental human influenza A virus inoculation in humans.22 In addition, following b.i.d. administration of 600 mg i.v. zanamivir, pulmonary distribution was adequate: epithelial lining fluid reached 65% of serum concentrations and Cτ in bronchoalveolar lavage was > 50‐fold higher than the IC90 values for influenza virus NA. This information suggests that concentrations achieved from the doses evaluated in phase II and phase III studies are on the upper portion of the exposure‐response curve. This indicates that when either 300 or 600 mg zanamivir is dosed b.i.d. similar results in PD end points were observed. The lower percentage of subjects with Cτ above IC90 for both influenza A and B strains predicted for q.d. dosing for both doses suggested that the b.i.d. dosing is necessary to keep the exposure in subjects with influenza above the IC90 values over the dosing interval (Table 3).

Funding

All clinical data were generated in studies sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline.

Conflict of Interest

M.O., A.B., G.R., H.A.W., A.P., P.Y., J.C. and M.H. are employees of and hold stock in GlaxoSmithKline. P.Z. is an employee of Astellas. D.S. is an employee of and holds stock in Urovant Sciences.

Author Contributions

M.O., P.Z., J.C., M.H., and A.B. wrote the article. A.P., H.A.W., G.R., P.Y., and D.S. designed the research. P.Z., J.C., and M.H. analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Change from baseline of viral load (quantitative virus culture) by exposure measures for day 1 and day 2.

Supplementary Tables S1–S8.

Acknowledgments

All clinical data were generated in studies sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from http://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

References

- 1. Dowdle, W.R. & Schild, G.C. Influenza: its antigenic variation and ecology. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 10, 193–195 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Colman, P.M. Influenza virus neuraminidase: structure, antibodies, and inhibitors. Protein Sci. 3, 1687–1696 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . FDA Approves a Second Drug for the Prevention of Influenza A and B in Adults and Children FDA press release. < https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2006/021036Orig1s008.pdf> (2006). Accessed April 2, 2018.

- 4. Webster, R.G. & Govorkova, E.A. Continuing challenges in influenza. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1323, 115–139 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. LaForce, C. et al Efficacy and safety of inhaled zanamivir in the prevention of influenza in community‐dwelling, high‐risk adult and adolescent subjects: a 28‐day, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Clin. Ther. 29, 1579–1590 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tisdale, M. Monitoring of viral susceptibility: new challenges with the development of influenza NA inhibitors. Rev. Med. Virol. 10, 45–55 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hurt, A.C. The epidemiology and spread of drug resistant human influenza viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 8, 22–29 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hibino, A. et al Community‐ and hospital‐acquired infections with oseltamivir‐ and peramivir‐resistant influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 viruses during the 2015–2016 season in Japan. Virus Genes 53, 89–94 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shelton, M.J. et al Zanamivir pharmacokinetics and pulmonary penetration into epithelial lining fluid following intravenous or oral inhaled administration to healthy adult subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 5178–5184 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pukrittayakamee, S. et al An open‐label crossover study to evaluate potential pharmacokinetic interactions between oral oseltamivir and intravenous zanamivir in healthy Thai adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 4050–4057 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beal, S.L. , Sheiner, L.B. , Boeckmann, A. & Bauer, R.J. NONMEM users guides. (NONMEM Project Group, University of California, San Francisco, CA, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergstrand, M. , Hooker, A.C. , Wallin, J.E. & Karlsson, M.O. Prediction‐corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed‐effects models. AAPS J. 13, 143–151 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gastonguay, M. Full covariate models as an alternative to methods relying on statistical significance for inferences about covariate effects: a review of methodology and 42 case studies. Paper presented at Athens, Greece: Abstract 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cockcroft, D.W. & Gault, H. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16, 31–41 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwartz, G.J. , Brion, L.P. & Spitzer, A. The use of plasma creatinine concentration for estimating glomerular filtration rate in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 34, 571–590 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Therneau, T.M. & Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, Germany, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spruance, S.L. , Reid, J.E. , Grace, M. & Samore, M. Hazard ratio in clinical trials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 2787–2792 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marty, F.M. et al Safety and pharmacokinetics of intravenous zanamivir treatment in hospitalized adults with influenza: an open‐label, multicenter, single‐arm, phase II study. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 542–550 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peng, A.W. , Hussey, E.K. , Rosolowski, B. & Blumer, J.L. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a single inhaled dose of zanamivir in children. Curr. Ther. Res. 61, 36–46 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cass, L.M. , Efthymiopoulos, C. & Bye, A. Pharmacokinetics of zanamivir after intravenous, oral, inhaled or intranasal administration to healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 36, 1–11 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bradley, J.S. et al Intravenous zanamivir in hospitalized patients with influenza. Pediatrics 140, e20162727 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calfee, D.P. , Peng, A.W. , Cass, L.M. , Lobo, M. & Hayden, F.G. Safety and efficacy of intravenous zanamivir in preventing experimental human influenza A virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43, 1616–1620 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Change from baseline of viral load (quantitative virus culture) by exposure measures for day 1 and day 2.

Supplementary Tables S1–S8.