Abstract

A voltammetric sensor based on the electropolymerization of cobalt-poly(methionine) (Co-poly(Met)) on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) was developed and applied for the determination of estriol by differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) for the first time. The electrochemical properties of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE were analysed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were used to characterize the polymers on the GCE surface. The deposition of the Co-poly(Met) film on the GCE surface enhanced the sensor electronic transfer. CV studies revealed that estriol exhibits an irreversible oxidation peak at +0.58 V for the Co-poly(Met)/GCE (vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode) in 0.10 mol/L Britton-Robinson buffer solution (pH = 7.0). Different voltammetric scan rates (10–200 mV/s) suggested that the estriol oxidation on the Co-poly(Met)/GCE surface is controlled by adsorption and diffusion processes. Based on the optimized DPV conditions, the linear responses for estriol quantification were from 0.596 μmol/L to 4.76 μmol/L (R2 = 0.996) and from 5.66 μmol/L to 9.90 μmol/L (R2 = 0.994) with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.0340 μmol/L and a limit of quantification (LOQ) of 0.113 μmol/L. The DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method provided good intra-day and inter-day repeatability with RSD values lower than 5%. Also, no interference of real sample matrices was observed on the estriol voltammetric response, making the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE highly selective for estriol. The accuracy test showed that the estriol recovery was in the ranges 96.7%–103% and 98.7%–102% for pharmaceutical tablets and human urine, respectively. The estriol quantification in pharmaceutical tablets performed by the Co-poly(Met)/GCE-assisted DPV method was comparable to the official analytical protocols.

Keywords: Estriol, Electroanalysis, Differential pulse voltammetry, Cobalt-poly(methionine) film-modified glassy carbon electrode

1. Introduction

Estriol is a steroidal hormone used to relieve the symptoms of postmenopause, while acting preventively against the occurrence of diseases in women, such as cardiovascular complications and osteoporosis [1]. Estriol is also found in pregnant mammals, in which the level of hormone excreted over the pregnancy period is about 1000-fold greater than the non-pregnant levels [2]. The biosynthesis of estriol occurs through fetal and placental reactions; thus its determination in urine and blood may be useful for monitoring the fetal-placental unit as well as it could serve as a fetal well-being indicator. Estriol has a hydrophobic character in its free form, but it is conjugated to water-soluble sulfates and glucuronides in the liver to be further excreted in the urine. These estriol-conjugated forms present in the urine are rapidly hydrolyzed, regenerating estriol to its free form [3,4] and, consequently, turning the hormone into a water pollutant, which may pose a threat to humans and aquatic organisms [5,6]. In this context, the development of efficient, sensitive and practical analytical methods for the determination of low estriol concentrations is of paramount important. Some analytical methods, including electrophoresis [7], mass spectrometry [8,9], immunoassays [[10], [11], [12]] and chromatography [13,14] have been used to determine estriol in biological fluids, such as urine, serum and amniotic fluid. Also, the official protocols for estriol quantification in pharmaceutical samples cited by the American Pharmacopoeia (USP 29), Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP XIV) and European Pharmacopoeia, are almost exclusively based on chromatographic methods [[15], [16], [17]], which present several disadvantages in terms of selectivity, cost, complex separation procedures, use of toxic organic solvents, and long analysis time [18,19]. On the other hand, electroanalytical methods have received considerable attention for the quantification of pharmaceuticals due to their high sensitivity, accuracy, precision, simplicity, low cost, riddance of laborious sample preparation procedures and low sensitivity to matrix effects [20,21]. Due to these characteristics, electroanalytical methods appear as suitable alternatives for estriol analysis in pharmaceutical formulations and biological fluids.

The development of electroanalytical methodologies relies on sensors that must exhibit high sensitivity, selectivity and robustness. The use of surface-modifying agents has become a common route to increase the sensitivity and selectivity of electrochemical sensors [5,[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Some electroanalytical methods have been developed for the quantification of estriol in pharmaceutical and biological samples using differents types of electrodes, including paraffin-impregnated graphite-modified electrode [26], Pt nano-clusters/multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified glassy carbon electrode [27], boron-doped diamond electrode [28] reduced graphene oxide-Sb2O5 hybrid nanomaterial for the design of a laccase-based biosensor [19], screen-printed electrode modified with carbon nanotubes [29], carbon paste electrode modified with ferrimagnetic nanoparticles [30], glassy carbon electrode modified with reduced graphene oxide, gold nanoparticles and potato starch [31], glassy carbon electrode modified with polyglycine [32] and glassy carbon electrode modified with reduced graphene oxide and silver nanoparticles [33].

Recently, the use of electropolymers as surface electrode modifying agents has received enormous attention because of their selectivity and sensitivity towards analytes, strong adherence to the electrode surface, ability to provide large surface areas by forming homogeneous films and ability to promote large electron transfer rates [34,35]. The electropolymerization of several molecules on the surface of glassy carbon electrodes has been applied for the selective determination of drugs in different matrices [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. In particular, electrodes modified by the electropolymerization of amino acids, such as glycine [[41], [42], [43]] l-cysteine [[44], [45], [46]], lysine [47,48] and histidine [49,50] have been successfully tested in the determination of drugs in different matrices. Poly(l-methionine)-modified electrodes have already been used as electrochemical sensors [[51], [52], [53]]. Also, electrodes modified with transition metal-amino acid complexes have been applied for the determination of drugs [54,55]. These modified electrodes improve the electrode reaction by significantly decreasing the redox overpotential, being the catalytic activity enhanced due to electronic interactions between the transition metal and functional groups of the chelating ligand [55]. However, only a few papers describe the use of glassy carbon electrode modified with transition metal and poly(l-methionine) for drug determination [56,57].

In this work, a Co-poly(methionine) film was obtained by the electropolymerization of methionine and its further complexation with cobalt ions to produce a cobalt-poly(methionine)-modified glassy carbon electrode (Co-poly(Met)/GCE). The surface properties of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE were examined by scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The Co-poly(Met)/GCE was then used to develop a DPV electroanalytical methodology for quantifying estriol in pharmaceuticals and human urine. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report in the literature on the determination of estriol using a Co-poly(Met)/GCE.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

Estriol, methyl alcohol and ethyl alcohol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Hydrochloric acid, potassium phosphate monobasic, potassium chloride, dibasic potassium phosphate, sodium hydroxide were supplied by Proquímios (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Phosphoric acid was purchased from Reagen (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Boric acid, glacial acetic acid, potassium ferricyanide and cobalt chloride II were purchased from QM (Cotia, Brazil), Carlo Erba (Milan, Italy), Neon (Sao Paulo, Brazil) and Scientific Exodus (Hortolândia, Brazil), respectively. The preparation of 0.10 mol/L phosphate buffer solution (PBS) was performed by mixing equimolar amounts of KH2PO4 (0.10 mol) and K2HPO4 (0.10 mol) in 1.0 L of ultrapure water. The 0.10 mol/L Britton-Robinson buffer solution (BRBS) was prepared by mixing acetic acid (0.040 mol), boric acid (0.040 mol) and phosphoric acid (0.040 mol) in 1.0 L of ultrapure water.

The pH of the PBS and BRBS was adjusted to desired values with 1.0 mol/L hydrochloric acid and 1.0 mol/L sodium hydroxide solutions. Stock estriol solution (1.4 × 10−2 mol/L) was prepared using methyl alcohol as a solvent, protected against light and it was further stored in a refrigerator at 4 − 6 °C. Standard estriol solutions were prepared daily by diluting the stock solution in 0.10 mol/L PBS. All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Apparatus

Voltammetric and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy experiments were carried out on an Autolab 1 PGSTAT 128 N potentiostat/galvanostat (Utrecht, Netherlands), operating with the software Autolab Nova version 1.10 for data collection and analysis. The electrochemical experiments were performed in a one-compartment Pyrex 1 glass cell (20.0 mL) mounted with three electrodes: the Ag/AgCl (3.0 mol/L KCl) reference electrode, the counter electrode composed of a 1.0 cm2 Pt foil and the bare glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with a diameter of 5.0 mm (BAS Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and the modified Co-poly(Met)/GCE, which were used as working electrodes.

SEM and EDS were conducted using a Hitachi TM3000 microscope. Determinations of pH were done with a Tec−5 pHmeter (Tecnal) calibrated with standard buffer solutions. All measurements were carried out at room temperature.

The electrochemical method proposed in this study was compared with the United States Pharmacopoeia protocol [15]. The spectrophotometric analysis was carried out on a UV-VIS 6000 double beam spectrophotometer (Allcrom). UV detection was performed at wavelength of 281 nm.

2.3. Preparation of Co-poly(Met)/GCE

Initially, the bare GCE was cleaned using a 0.50 μm alumina suspension, followed by ultrasonic bath in ethanol for 5 min to remove adsorbed alumina particles. The electrode was rinsed with deionized water and allowed to dry at room temperature. The electropolymerization of l-methionine on the cleaned GCE surface was carried out by cyclic voltammetry (CV) with basis on previous studies [53,54]. The GCE surface was completely electropolymerized using 1.0 mmol/L methionine and 5.0 mmol/L CoCl2·6H2O in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 4.0) by 10 cycles in the potential range of −0.6 to +2.0 V at scan rate of 100 mV/s (Fig. S1).

2.4. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS was used to characterize the interface properties of the surface-modified electrodes. EIS measurements were carried out using the formal potential of [Fe(CN)6] −3/−4 redox couple using a mixed 1.0 mmol/L Fe(CN)63− + Fe(CN)64− (1:1) solution in 1.0 mol/L KCl and frequency range of 0.10 Hz–105 Hz. The value of Rct was obtained by non-linear regression analysis of the semi-circular portion of the Nyquist plots (Zim vs. Zre).

2.5. Scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM)

SECM was performed on a CHI 920C microscope (CH Instruments). SECM measurements were performed at room temperature in a Teflon electrochemical cell with aperture of 10 mm, using a four electrode configuration. A Pt disk-shaped ultramicroelectrode (UME) tip with radius (a) of 5.0 μm and the sample were used as first and second working electrodes, respectively. A Pt wire served as an auxiliary electrode, while Ag|AgCl|3.0 mol/L KCl was used as the reference electrode. A combination of 8.0 nm-resolution positioners driven by stepper motors, 50 mm travel distance and tip position adjusted by a XYZ piezo-block was used. The ratio (RG) between the insulating glass radius (rg) and UME active area radius (a) was approximately 5.0. The tip was held at a constant potential throughout all experiments.

2.6. Electrochemical measurements

The electrochemical behaviour of estriol on the bare GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE previously risen with deionized water was investigated by CV at scan rate of 100 mV/s over the potential range from −0.1 to +0.8 V. A volume of 9.0 mL of 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) was placed into the glass electrochemical cell and, afterwards, it was submitted to 10 scan rate cycles at 100 mV/s to stabilize the electrode surface in this blank solution. Then, 1.0 mL of the 1.4 mmol/L estriol solution was added to the electrochemical cell and the scan rate was varied from 10 to 200 mV/s. Cyclic voltammograms were also recorded at 100 mV/s for 1.4 × 10−4 mol/L estriol in 0.10 mol/L BRBS with pH varying from 2.0 to 12.0 to study the pH-dependence of the estriol electrochemical behaviour in relation to the Co-poly(Met)/GCE.

The analytical method for estriol determination was developed by DPV. The pulse amplitude (a) and scan rate (v) were selected as the main parameters to optimize the experimental conditions for the quantification of estriol using the Co-poly(Met)/GCE. Briefly, 10.0 mL of 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) containing 1.4 × 10−4 mol/L estriol were placed in the glass electrochemical cell and the pulse amplitude was varied from 10 to 100 mV with the scan rate fixed at 5.0 mV/s. Next, the scan rate (v) was varied from 1.0 to 7.0 mV/s, while the pulse amplitude was fixed at 60 mV. The linearity of the method was evaluated by preparing 13 estriol solutions (0.596 – 9.90 μmol/L) for three different days. The linear correlation coefficient was determined from the analytical curve by linear regression.

The limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were determined using the ratios 3σ/b and 10σ/b, respectively, where b is the calibration curve slope and σ is the standard deviation calculated from ten voltammograms perfomed on the blank according to the IUPAC recommendations [58]. All electrochemical measurements were conducted at room temperature. These experimental conditions and optimized DPV parameters were used to quantify estriol in a pharmaceutical formulation and human urine.

2.7. Preparation of samples for quantification of estriol by DPV

2.7.1. Human urine samples

Human urine samples were collected from voluntaries and stored at 4.0 °C. The determination of estriol in the urine samples (2.0 μmol/L) was performed in the linear range of the analytical curve to verify the applicability of the DVP method. The estriol-fortified urine sample was prepared with addition of 75 μL of the 1.0 × 10−2 mol/L standard stock estriol solution to a 10.0 mL volumetric flask, which was completed with urine to its final volume, resulting in a final estriol concentration of 7.5 × 10−5 mol/L. Next, an aliquot of 275 μL of this estriol-urine solution was transferred to the electrochemical cell containing 10.0 mL of 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) and the electrochemical measurement was performed. Next, standard estriol solution was added following the standard addition method.

2.7.2. Tablet samples containing estriol

The DVP method was tested for the determination of estriol in pharmaceutical formulations (tablets). Estriol tablets were purchased at a local drugstore. According to the manufacturer's information, each tablet contained 2.0 mg of estriol. Five tablets were pulverized and, subsequently, the powder was transferred to a 10.0 mL volumetric flask and mixed with 5.0 mL of methanol. The mixture was sonicated for 30 min and further diluted with methanol to the final volumetric flask volume. This solution was centrifuged for 5 min so that the undissolved excipients were decanted. An aliquot of the supernatant (144 μL) was transferred to another 5.0 mL volumetric flask, which was completed with methanol to its final volume. Next, 200 μL of this solution was diluted in 10.0 mL of 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) in the electrochemical cell and the estriol concentration was determined by the standard addition method. The results were compared with an official US Pharmacopoeia protocol [15].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Electrochemical behaviour of estriol on bare GCE, poly(Met)/GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE

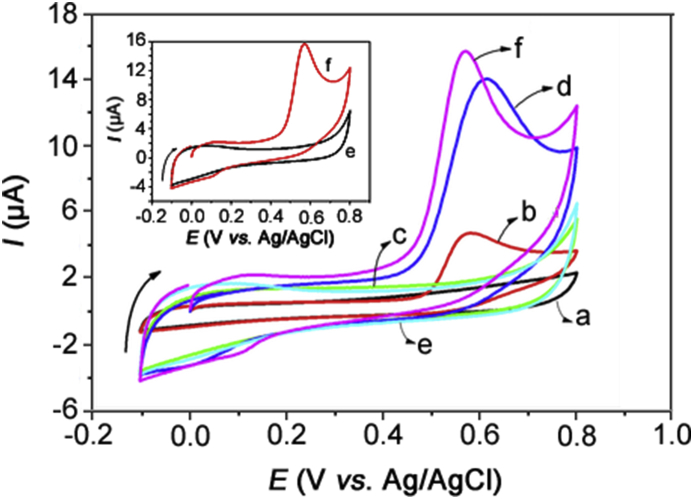

The electrochemical behaviour of estriol (0.14 mmol/L) in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) was investigated by CV at 100 mV/s over the potential range from −0.1 to +0.8 V. Based on the bare GCE, poly(Met)/GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE (Fig. 1), estriol showed an irreversible oxidation peak at +0.58 V (Fig. 1 curve b), +0.61 V (Fig. 1 curve d) and +0.57 V (Fig. 1 curve f), respectively. It is possible to verify that the estriol oxidation on the poly(Met)/GCE occurred at a higher potential than that observed for the Co-poly(Met)/GCE and the peak current obtained with the Co-poly(Met)/GCE was 3-fold larger than that observed with the bare GCE. These results suggest that the deposition of the Co-poly(Met) complex on the GCE surface enhanced the electron transfer process. This is because the cobalt ions used to produce the metal-poly(Met) film on the electrode surface act as an “electron shuttle” to carry electrons from the substrate, causing a significant increase in the peak current. The Co-poly(Met)/GCE was then used as a sensor to develop the electroanalytical methodology for estriol determination.

Fig. 1.

Cyclic voltammograms obtained with bare GCE in the absence (a) and presence (b) of estriol, poly(Met)/GCE in the absence (c) and presence (d) of estriol, and Co-poly(Met)/GCE in the absence (e) and presence (f) of estriol. [Estriol] = 0.14 mmol/L in 0.1 mol/L PBS, pH = 7.0, v = 100 mV/s. Inserted graph: Cyclic voltammograms obtained only with Co-poly(Met)/GCE in the absence (e) and presence (f) of estriol.

The insert in Fig. 1 shows the voltammograms obtained using the Co-poly(Met)/GCE electrode for the pure 0.10 mol/L PBS solution (pH = 7.0) (blank solution) and with 0.14 mmol/L estriol. It is observed that in the blank solution (red line, (e)) no signals related to the Co-poly(Met) complex were recorded in the potential range from −0.1 V to +0.8 V. However, as mentioned before, in the presence of estriol (black line, (f)), a well-defined irreversible oxidation peak was observed at +0.57 V peak potential (Ep) using the Co-poly(Met)/GCE. This oxidation peak is attributed to the oxidation of the phenolic hydroxyl group in the estriol molecule [5,6,26,29,30].

3.2. Influence of the methionine and CoCl2·6H2O concentrations on the sensor response

To optimize the preparation of the sensor, the concentration of methionine and CoCl2·6H2O was investigated. First, the influence of the methionine concentration on the sensor response was investigated by preparing solutions containing different methionine concentrations (1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10 and 20 mmol/L) in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH 4.0), while the CoCl2·6H2O concentration was kept at 0.10 mol/L. The results indicate that the highest peak current was obtained using methionine at 5.0 mmol/L. The use of methionine concentrations lower than 5.0 mmol/L resulted in low responses probably due to the small amount of the amino acid that was insufficient to form a poly(Met) film on the electrode surfaces. On the other hand, the use of methionine concentrations higher than 5.0 mmol/L did not increase the oxidation peak current. Based on these results, the 5.0 mmol/L methionine concentration was chosen to prepare the sensor.

The response of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE was also affected by the initial CoCl2·6H2O concentration, which was varied (0.01, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20 and 0.50 mol/L) in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH 4.0), while the methionine concentration was maintained at 5.0 mmol/L. Based on the results, the current response significantly increased with the increasing CoCl2·6H2O concentration up to 0.10 mol/L. The use of CoCl2·6H2O concentration lower than 0.10 mol/L resulted in low responses probably due to the small amount of metal on the Co-poly(Met) film. On the other hand, the use of CoCl2·6H2O concentrations higher than 0.10 mol/L did not enhance the sensor response, which could be related to a maximum ability of methionine to form complexes with the Co2+ ions. Hence, the 0.10 mol/L CoCl2·6H2O solution was chosen to prepare the sensor.

3.3. Electropolymerization of methionine and cobalt on GCE

An anodic irreversible peak was observed in the first voltammetric cycle during the electropolymerization of 1.0 mmol/L methionine and 5.0 mmol/L CoCl2·6H2O in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 4.0) on the GCE (Fig. S1). After several successive cycles, the oxidation peak disappeared completely because the poly(l-methionine) film was formed on the GCE surface. This behaviour was also observed in previous studies, in which l-methionine was used to modify solid electrodes [[51], [52], [53]]. The reaction mechanism has been explained in a previous report [51]. The poly(l-methionine) structure possesses N atoms and carboxyl oxygen atoms because methionine acts as a chelating ligand. Transition metal ions such as Co2+ can effectively form a transition metal complex with poly(l-methionine) through covalent bonding. Structural studies reported in the literature on transition metal complexes have shown that amino acids can coordinate with metal ions through several mechanisms, depending on the metal ion and its oxidation state, and the primary amino acid structure [59].

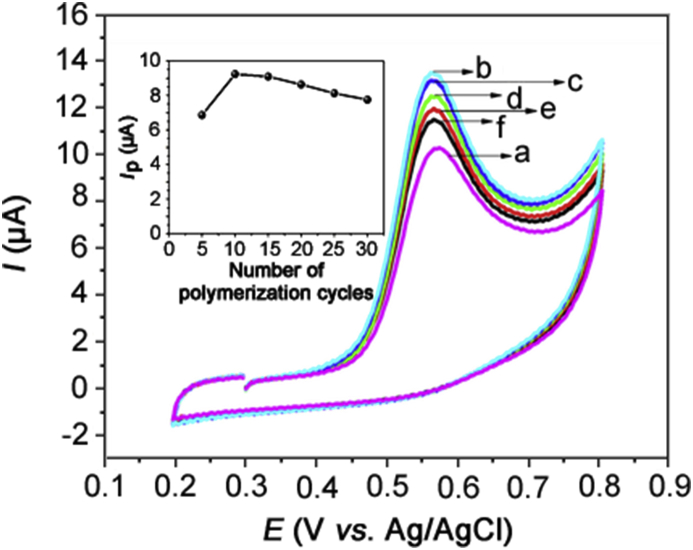

The effect of the Co-poly(Met) film thickness on the estriol anodic peak current was also evaluated. It is well known that film thickness can be easily controlled by the number of cyclic scans. CV experiments were conducted on 0.14 mmol/L estriol in 0.10 mol/L BRBS (pH = 7) solution in the range from +0.2 to +0.8 V with the Co-poly(Met)/GCE obtained from 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 cycles. It was observed that the estriol current response increased with the increasing cyclic scan number up to 10 and further decreased, as shown in Fig. 2. This result suggests that the electropolymerization performed with more than 10 cycles decreases the conductance and sensitivity of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE. Therefore, 10 potential cyclic scans were adopted as the optimal condition for fabricating the Co-poly(Met)/GCE.

Fig. 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of 0.14 mml/L estriol in 0.1 mol/LPBS buffer, pH = 7, recorded with the Co-poly(Met)/GCE obtained from (a) 5, (b) 10, (c) 15, (d) 20, (e) 25 and (f) 30 polymerization cycles at v = 100 mV/s. Inserted graph: peak current versus number of polymerization cycles.

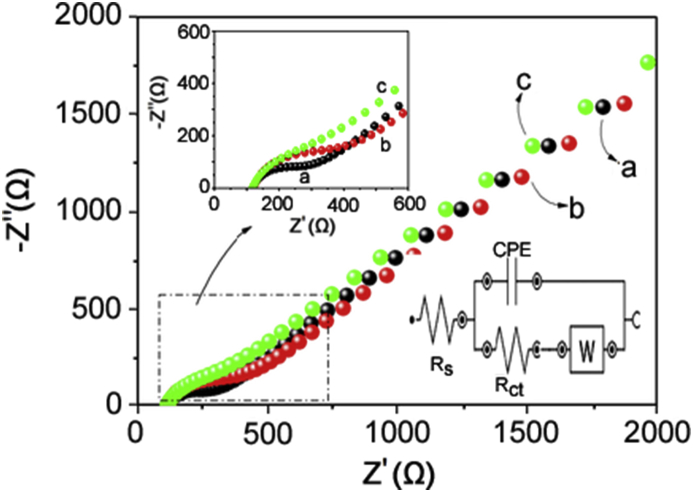

3.4. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis

EIS was used to investigate the electrode/solution interface properties. The Nyquist plots for GCE, poly(Met)/GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE, and the equivalent circuit used to fit the obtained EIS data are shown in Fig. 3. The semicircle diameter observed in the Nyquist diagrams is equal to the electron transfer resistance (Rct), which controls the electron transfer characteristics of the redox probe on the electrode surface [60,61].

Fig. 3.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data of bare CGE (curve a), poly(Met)/GCE (curve b) and Co-poly(Met)/GCE (curve c). Measurements were carried out using a 1.0 mmol/L [Fe(CN)6]3−/[Fe(CN)6]4− solution containing 0.1 mol/L KCl as a supporting electrolyte. Inserted graphs: Nyquist graph of the selected region in the figure and Randles equivalent circuit model, where the equivalent circuit parameters such as Rs, Rct, CPE and W represent the solution resistance, the electron transfer resistance, the constant phase element corresponding to the double-layer capacitance and the Warburg constant, respectively.

As displayed in Fig. 3, the GCE and poly(Met)/GCE show semi-circular and linear parts at high and low frequencies, respectively. The Rct, solution resistance (Rs), constant phase element corresponding to the double-layer capacitance (CPE) and Warburg constant (W) values for GCE were 134 Ω, 122 Ω, 1.55 μF and 509 μMho, respectively. The poly(Met)/GCE produced a semi-circle with higher radius than that obtained with the GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE, and it provided a high resistance to charge transfer, indicating a slow electron transfer process. For poly(Met)/GCE, the Rct and CPE values increased to 197 Ω and 3.96 μF, respectively, in comparison with the GCE. This larger resistance is attributed to the low electrical conductivity of the poly(Met) film, which hampers the electronic transfer on the electrode surface. For poly(Met)/GCE, the Rs and W values were 123 Ω and 501 μMho, respectively. The Co-poly(Met)/GCE produced a quasi-linear Nyquist plot with no semicircle with Rct of 123 Ω. This result indicates a rapid electron transfer with [Fe(CN)6] −3/−4. The electron transfer between the redox probe and electrode surface may be facilitated due to the good conductivity of the Co2+ ions. Thus, the electron transfer rate between the electrode and redox species in solution was considerably increased due to the presence of the Co-poly(Met) film. It is clear from the Rct values that the presence of Co and poly(methionine) in the GCE improves the charge transfer kinetics. For Co-poly(Met)/GCE, the Rs, CPE and W values were 120 Ω, 11.9 μF and 509 μMho, respectively. The least value of Rct was observed for Co-poly(Met)/GCE, hence this electrode was used to develop the electrochemical sensor for quantification of estriol.

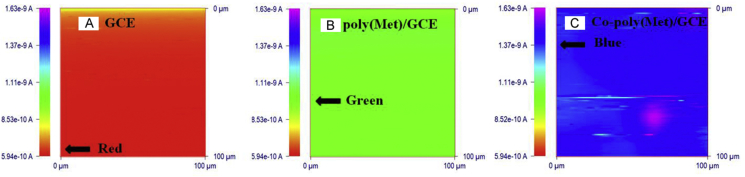

3.5. SECM images of bare GCE, poly(Met)/GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE

SECM has been proven to be a valuable technique for quantitative investigation and surface analysis of a wide range of interface processes [62]. The cyclic voltammograms were recorded with the 5.0 μm-radius Pt tip positioned at a working distance (d) higher than 200 μm. SECM images of the bare GCE, poly(Met)/GCE and Co-poly(Met)/GCE are shown in Figs. 4A, B and C, respectively, which illustrate scans over a 250 μm × 250 μm electrode area. The Pt tip was moved in close proximity to the sample surface with potential held at −0.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl, while the sample potential was +0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

Fig. 4.

SECM images (x-y scans) of the (A) bare GCE surface, (B) poly(Met)/GCE surface and (C) Co-poly(Met)/GCE surface. SECM imaging was performed with a 10 mm-width Pt microelectrode in 1.0 mmol/L [Fe(CN)6]3− solution as a redox mediator containing 0.1 mol/L KCl as a supporting electrolyte.

The solution in which the tip and substrate (bare GCE, poly(Met)/GCE or Co-poly(Met)/GCE) are immersed contained [Fe(CN)6]3−, as an electroactive species, and the supporting electrolyte to minimize the solution resistance. If the potential at the SECM tip is enough to reduce [Fe(CN)6]3− to [Fe(CN)6]4−, at a diffusion-limited rate, the current rapidly achieves a steady-state value, which is proportional to the [Fe(CN)6]3− concentration. When the tip is moved toward the conductor substrate surface held at a potential sufficient to oxidize [Fe(CN)6]4− back to [Fe(CN)6]3−, the current at the tip increases due to the recycling of the [Fe(CN)6]3− species. This “feedback” process is an important feature of SECM. When the tip is moved in the x-y plane above the substrate, the tip current variation represents changes in topography or conductivity (or reactivity) [61,62]. The current-feedback direction indicates the nature of the surface (i.e. electrically conducting or insulating surface), while the signal magnitude is an indication of the distance between the tip and substrate or, alternatively, the turnover species rate at the substrate surface [62].

It can be seen in Fig. 4 that the surface of the bare GCE (Fig. 4A), poly(Met)/GCE (Fig. 4B) and Co-poly(Met)/GCE (Fig. 4C) are flat with no topographic changes, indicating that all electrode surfaces are uniform and active. The current-feedback indicates an electrically conductive nature for all electrodes. Furthermore, the Co-poly(Met)/GCE showed higher tip currents when compared to the bare GCE and poly(Met)/GCE. As mentioned previously, the magnitude of the signal is proportional to the species turnover rate. This result shows that the [Fe(CN)6]3− regeneration at the Co-poly(Met)/GCE surface is faster than those occurring on the bare GCE and poly(Met)/GCE surfaces due to the better electron transfer properties of the Co-poly(Met) film. Also, it is possible to conclude from Fig. 4 that there are more active sites on the Co-poly(Met)/GCE surface rather than on the other electrodes due to the uniform deposition of the Co-poly(Met) film.

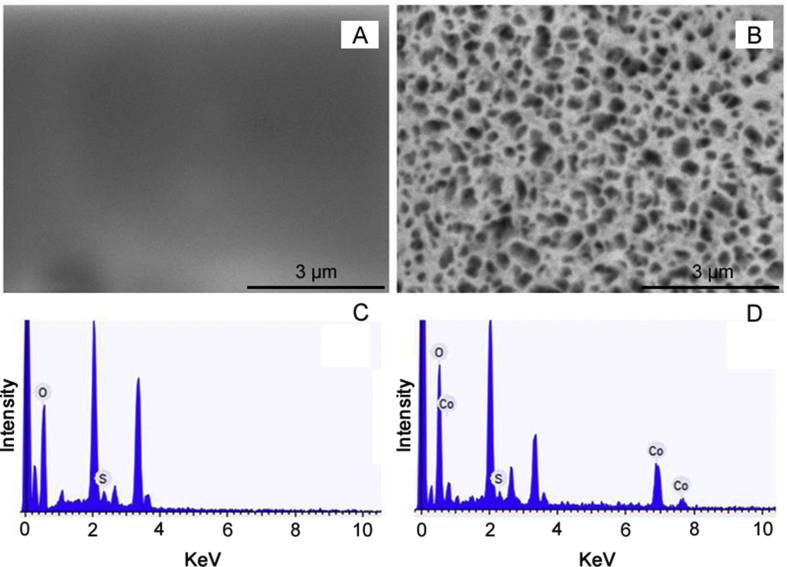

3.6. Morphological characterization of films

SEM was performed to characterize the morphology of the poly(Met) and Co-poly(Met) films on the GCE surface. It is possible to observe that the poly(Met) film (Fig. 5A) shows a smooth and homogeneous surface. However, the Co-poly(Met) film (Fig. 5B) was characterized by a porous morphology that reduces the diffusion resistance and facilitates the mass transport because of its higher internal surface area. The EDS image of the poly(Met) film (Fig. 5C) shows the presence of O and S atoms related to the methionine molecular structure. Furthermore, the EDS image of the Co-poly(Met) film (Fig. 5D) shows the presence of O, S and Co. These results suggest the formation of complexes between the Co2+ ions and poly(Met) film, as reported in the literature [59].

Fig. 5.

SEM images for (A) poly(Met) and (B) Co-poly(Met) films. EDS images for (C) poly(Met) and (D) Co-poly(Met) films.

3.7. Effect of pH on the determination of estriol

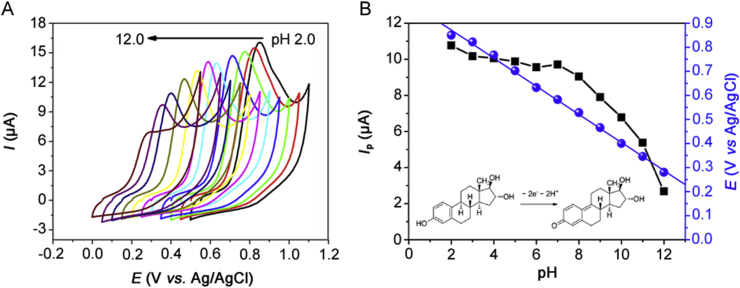

Fig. 6A shows the cyclic voltammograms obtained for 0.14 mmol/L estriol in 0.10 mol/L BRBS at 100 mV/s in the pH range 2.0–12.0. The pH-dependence of the peak potential (Ep) and peak current (Ip) is shown in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 6.

(A) Cyclic voltammograms of 0.14 mmol/L estriol in 0.1 mol/L BRBS at pH 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0, 11.0 and 12.0 obtained with the Co-poly(Met)/GCE at v = 50 mV/s. (B) Effect of pH on estriol peak current (blue line) and estriol peak potential (black line). Inserted graph: proposed oxidation reactions for estriol on Co-poly(Met)/GCE.

It was observed that the peak potentials shifted towards more negative values with the increasing pH. The linear relationship between the estriol oxidation peak potential (Ep) and supporting electrolyte pH is given by the following equation:

| (1) |

The slope of 0.058 V in Eq. (1) agrees with the Nernstian slope of 0.059 V/pH unit at 25 °C [58]. The results suggest that an equal number of protons and electrons are involved in the estriol redox process on the Co-poly(Met)/GCE. The number of electrons involved in the estriol oxidation process can be determined by the following equation: |Ep − Ep/2| = 47.7 mV/αn, which is applicable for irreversible systems [61]. The difference between the peak potential (Ep) and the half-wave peak potential (Ep/2) values was obtained using the voltammogram obtained for the estriol oxidation in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH 7.0) (Fig. 1). The mean (Ep − Ep/2) value was 48.0 mV and by applying the above equation the value αn = 0.99 was obtained. Considering the transfer coefficient (α) of 0.5, which is typically used for organic compounds when the experimental value is not available, the number of electrons transferred (n) in the estriol oxidation was found to be approximately 2. Besides, using the linear regression slope (58.0 mV) and replacing it in the equation ΔE/ΔpH = (59.1 mV/n) × NH+, where n = 2, it is possible to calculate the number of protons (NH+) transferred in the estriol oxidation process. The number of protons (NH+) calculated was equal to 1.96. In this case, the electrochemical oxidation of estriol is suggested to occur in the phenolic hydroxyl group, according to a two-electron/two-proton reaction, as displayed in the insert of Fig. 6B. These results corroborate with the electrochemical behaviour of estriol in other electrodes [30].

The pH influence on the estriol peak current was also investigated. As shown in Fig. 6B, the anodic peak current (Ip) of estriol did not vary notably in the pH range 2.0–7.0. In addition, the anodic current peak (Ipa) decreased for pH values between 8.0 and 12.0. Thus, the optimum pH for further studies was set at 7.0, which is also similar to the physiological pH.

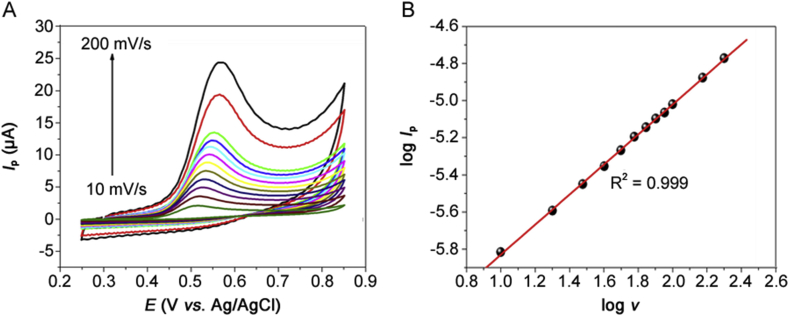

3.8. Effect of scan rates on cyclic voltammetry

It is possible to characterize redox processes on surfaces of flat or spherical electrodes by means of CV, considering the influence of the scan rate (v) on the peak current and potentials related to the analyte [63]. To characterize the electrochemical reaction of estriol on the Co-poly(Met)/GCE, additional CV studies were performed. Cyclic voltammograms for 0.14 mmol/L estriol in PBS 0.10 mol/L (pH = 7.0) upon variation of scan rate are presented in Fig. 7A.

Fig. 7.

(A) Cyclic voltammograms of 0.14 mmol/L estriol in 0.1 mol/L PBS buffer, pH = 7.0, obtained with Co-poly(Met)/GCE at different scan rates. (B) Logarithm of the oxidation peak current versus the logarithm of the scan rate.

The estriol oxidation on the Co-poly(Met)/GCE was scan rate-dependent, as shown in Fig. 7A. The estriol oxidation peak potential was shifted from 30 mV/αn to more positive values with the ten-fold increasing scan rate, confirming the irreversible character of the estriol oxidation reaction. The scan rate (ν) effect on the estriol oxidation peak current was also evaluated. The peak current increased linearly with the increasing scan rate over the range 10–200 mV/s. Also, the peak current was found to be linearly proportional to the square root of the scan rate. The good linearity, in both cases (Ip vs. v and Ip vs. v1/2), indicates that the estriol oxidation is irreversible and limited by an adsorption and/or diffusion process at the Co-poly(Met)/GCE interfacial region. Linear Ip vs. v and Ip vs. ν1/2 relationships are expressed by equations (2), (3), respectively:

| (2) |

| (3) |

The linear coefficient values were not null, which is an indicative of adsorption processes [61,63]. To demonstrate whether the determinant step in the reaction rate has adsorptive or diffusive nature, a plot of log Ip vs. log v was obtained (Fig. 7B), leading to a linear relationship with the corresponding equation (4):

| (4) |

According to the literature [[64], [65], [66]], a plot of log Ip vs. log v will be a straight line of slope 0.5 if the system is purely diffusional and 1.0 if the species is bonded to the electrode surface. Slope values between 0.5 and 1.0 represent mixed systems where the value is indicative of the contribution of both adsorptive and diffusional mechanisms. The slope value was 0.809, indicating a combined diffusive/adsorptive nature of the determinant step in the estriol oxidation process [[64], [65], [66]].

The electron transfer coefficient (α) for the Co-poly(Met)/GCE was calculated to be 0.48 using equation |Ep − Ep/2| = 47.7 mV/αn, which is applicable to irreversible systems [61]. The Ep and Ep/2 values were obtained at different scan rates (10–200 mV/s). The mean potential difference was 51 mV and yielded α = 0.48.

3.9. Effect of pulse amplitude (a) and scan rate (v) on DPV

To develop the DPV method for estriol quantification, the parameters determining the current signal, such as pulse amplitude (a) and scan rate (v), were optimized. This optimization was conducted using 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) containing estriol at 0.14 mmol/L. Each parameter was varied while keeping the others at a constant value. For example, the amplitude was ranged from 10 to 100 mV, while the scan rate was fixed at 5.0 mV/s (Fig. S2). It was found that the estriol oxidation peak current increased with the increasing amplitude over the range 10–100 mV, whereas the estriol peak potential (Ep) shifted towards less positive values. Furthermore, the estriol oxidation peak broadened for amplitude values above 60 mV, resulting in a decreased method resolution. The scan rate (v) was then varied over the range 1.0–7.0 mV/s with amplitude fixed at 60 mV. No variation of the peak potential was observed and there was only a slight increase in the peak current with the increasing v up to 5.0 mV/s. The Ip intensity decreased for scan rates greater than 5.0 mV/s (Fig. S3). Therefore, the optimized DVP parameters (amplitude of 60 mV and scan rate of 5.0 mV/s) were used to determine the analytical curves.

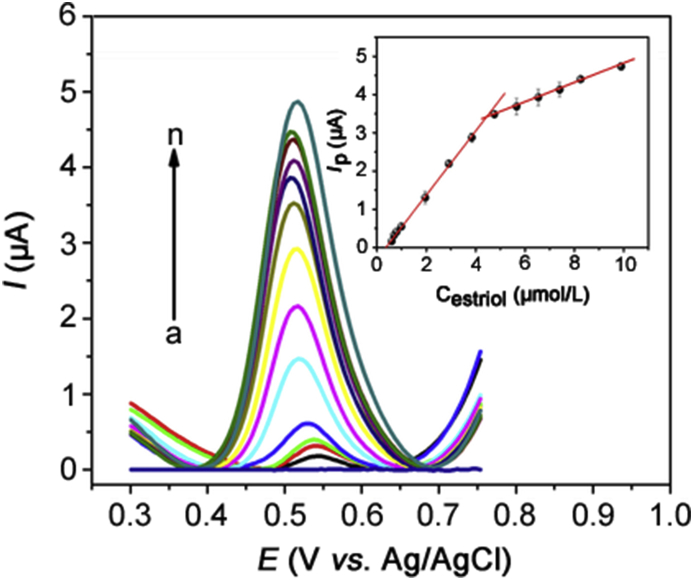

4. Analytical curve and comparison of the DPV method with other electrochemical methods

The applicability of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE-assisted DPV method for the quantification of estriol was examined from analytical curves (current peak vs. estriol concentration) obtained under optimized experimental conditions. Fig. 8 shows the differential pulse voltammograms registered after addition of standard solution aliquots (triplicate) with increasing estriol concentrations (0.596–9.90 μmol/L) in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7).

Fig. 8.

DPV voltammograms obtained for oxidation of estriol under optimized conditions at different concentrations: 0.00 (a), 0.596 (b), 0.695 (c), 0.794 (d), 0.990 (e), 1.96 (f), 2.91 (g), 3.85 (h), 4.76 (i), 5.66 (j), 6.54 (k), 7.41 (1), 8.26 (m) and 9.90 µmol/L (n) using Co-poly(Met)/GCE. Inserted graph: analytical curve plot.

The analytical curve is shown in the inset of Fig. 8. It is possible to observe that there was a linear correlation between the peak current and estriol concentration in the ranges 0.596–4.76 μmol/L and 5.66–9.90 μmol/L. The linear relationships are expressed by equations (5) (0.596–4.76 μmol/L) and 6 (5.66–9.90 μmol/L), respectively.

| (5) |

| (6) |

The two linear regions may be ascribed to the saturation of the Co-poly(Met) film with estriol molecules. This behaviour decreases the sensitivity (slope) of the electrode in the second linear region of the calibration curve probably due to the formation of an estriol sub-monolayer in the first range of the calibration curve and formation of a monolayer in the second range.

The LOD of 3.40 × 10−8 mol/L and LOQ of 1.13 × 10−7 mol/L were determined with basis on the 3σ/slope and 10σ/slope ratios, respectively, where σ is the standard deviation obtained from ten voltammograms performed on the blank solution as per the IUPAC recommendations [58].

The linear range and LOD of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE-assisted DPV method were comparable or better than those of other electroanalytical techniques previously reported for the determination of estriol in pharmaceutical and/or urine samples (Table 1). The advantages exhibited by the Co-poly(Met)/GCE, principally the high sensitivity (0.836 μA/μmol L−1), low detection limit and simplicity, demonstrate that this electrode could be potentially used as an electrochemical sensor for the quantification of estriol in pharmaceutical samples and urine.

Table 1.

Comparison between the Co-poly(Met)/GCE-assisted DPV method and other electrochemical methods for estriol determination.

| Electrode | Technique | Linear range (µmol/L) | Limit of detection (mol/L) | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCh/WGE | SWV | 0.5–9.0 | 5.0 × 10−8 | Blood serum | [26] |

| GCE/Pt/MWCNTs | SWV | 10.0–75.0 | 6.2 × 10−7 | Blood serum | [27] |

| BDDE | SWV | 0.2–20.0 | 1.7 × 10−7 | Pharmaceutical and urine | [28] |

| GCE/Lac/rGO/Sb2O5 | Chronoamperometry | 0.025–1.0 | 1.1 × 10−8 | Urine | [19] |

| SPCE/CNT | Amperometry | 1.0–1000 | 5.3 × 10−7 | Pharmaceutical | [29] |

| CPE/Fe3O4NPs | SWV | 3.0–110.0 | 2.6 × 10−6 | Pharmaceutical and simulated urine | [30] |

| RGO-GNPs-PS/GCE | LSV | 1.5–22.0 | 4.8 × 10−7 | Water and urine | [31] |

| PGMCPE | CV | 2.0–100.0 | 8.7 × 10−7 | Injections | [32] |

| rGO/AgNPs/GCE | DPV | 0.1–3.0 | 2.1 × 10−8 | Tap water and synthetic urine | [33] |

| Co-poly(Met)/GCE | DPV | 0.596–9.90 | 3.4 × 10−8 | Pharmaceutical and urine | This work |

CCh/WGE: Carbamylcholine (CCh) modified paraffin-impregnated graphite electrode; GCE/Pt/MWCNTs: Pt nanoclusters and multi-wall carbon nanotubes composite glassy carbon electrode; SWV: square-wave voltammetry; BDDE: boron doped diamond electrode; Lac/rGO/Sb2O5: reduced graphene oxide doped with Sb2O5 film and with immobilized laccase enzyme; SPCE/CNT: screen-printed carbon electrode modified with carbon nanotubes; CPE/Fe3O4NPs: carbon paste electrode (CPE) modified with ferrimagnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4NPs). GNPs: Gold nanoparticles; PS: Potato starch; PG: poly glycine; MCPE; modified carbon paste electrode; AgNPs: Silver nanoparticles.

4.1. Intra-day and inter-day repeatability

The intra-day repeatability of the peak current intensity was determined by successive measurements (n = 6) on the 3.0, 5.0 and 10.0 μmol/L estriol solutions in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0). Comparison of these repeated peak currents with the initial value provided the relative standard deviations (RSD) of 4.00%, 1.94% and 2.37%, respectively, indicating a good intraday repeatability of the Co-poly(Met)/GCE-assisted DPV method. Likewise, the inter-day repeatability of the peak current intensity for the 3.0, 5.0 and 10.0 μmol/L estriol solutions in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.0) was evaluated by registering the peak current over a period of 6 days, leading to RSD values of 4.13%, 2.66% and 2.11%, respectively. Hence, it is concluded that the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE approach provides an adequate inter-day repeatability for estriol determination.

4.2. Study of interference

The selectivity of the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method in relation to the estriol determination was tested by the assessment of the interference of substances usually present in human urine (such as uric acid, ascorbic acid and citric acid) and in pharmaceutical formulations (such as stearate magnesium, starch, and lactose). Solutions of such compounds were freshly prepared at an estriol to compound concentration ratio of 1:5000 using the same conditions used for the preparation of 4.80 μmol/L estriol in 0.10 mol/L PBS (pH 7.0). The estriol anodic peak currents measured by DPV were compared with those obtained with no addition of interfering compound. The relative responses for lactose, magnesium stearate, starch, uric acid, ascorbic acid, citric acid were 97.3(±2.3), 96.2(±2.1), 104(±3), 98.4(±2.5), 98.7(±1.5), 97.7(±1.8), respectively, indicating that the changes of current signal were not significant in comparison with the pure estriol solution current. These results confirm that the presence of the selected interfering compounds did not alter the determination of estriol using the Co-poly(Met)/GCE.

4.3. Application of the DPV method for estriol determination in pharmaceuticals formulations and urine and recovery tests

The DVP-Co-poly(Met)/GCE was used to quantify estriol in pharmaceuticals tablets and human urine. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate using the standard addition method. For comparison purposes, the estriol concentration in the tablets was also determined by the official spectrophotometric protocol [15]. Data were statistically compared through the t-test and F-test [67] and the results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of estriol determination in pharmaceutical samples using the electroanalytical DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method and the official spectrophotometric protocol [15].

| Pharmaceutical sample | Label value (mg/tablet) | Proposed method (mg/tablet, n = 3) | Official protocol (mg/tablet, n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.00 | 2.02 ± 0.03 | 2.01 ± 0.02 |

| B | 2.00 | 1.99 ± 0.02 | 2.02 ± 0.03 |

| C | 2.00 | 2.05 ± 0.04 | 2.00 ± 0.01 |

| D | 2.00 | 1.99 ± 0.01 | 1.99 ± 0.02 |

| E | 2.00 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 2.00 ± 0.01 |

It is verified from Table 2 that there was no statistical difference between the DVP-Co-poly(Met)/GCE and spectrophotometric method at a confidence level of 95.0%, indicating that the Co-poly(Met)/GCE can be successfully used for voltammetric determinations of estriol in pharmaceutical formulations. The accuracy of the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method and the matrix interference effects were further checked by analytical recovery experiments. Precise amounts of estriol (0.970, 1.92, and 2.86 μmol/L) were added to pharmaceutical tablet samples. The human urine samples were also fortified with estriol (0.960, 1.91 and 2.84 μmol/L). The recovery percentage values were calculated from the actual and added estriol concentrations, as reported in Table 3, Table 4. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate to increase the data reliability.

Table 3.

Estriol addition-recovery experiment results for pharmaceuticals samples using the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method.

| Pharmaceutical sample | [Estriol] added (μmol/L, n = 3) | [Estriol] expected (μmol/L, n = 3) | [Estriol] found (μmol/L, n = 3) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.00 | – | 1.98(±0.03) | – |

| 0.970 | 2.95 | 2.98(±0.14) | 101(±5) | |

| 1.92 | 3.90 | 3.95(±0.08) | 101(±2) | |

| 2.86 | 4.84 | 4.68(±0.01) | 96.7(±0.3) | |

| B | 0.00 | – | 1.96(±0.02) | – |

| 0.970 | 2.93 | 2.95(±0.06) | 101(±2) | |

| 1.92 | 3.88 | 3.95(±0.05) | 102(±1) | |

| 2.86 | 4.82 | 4.76(±0.03) | 98.8(±0.6) | |

| C | 0.00 | – | 2.01(±0.04) | – |

| 0.970 | 2.98 | 2.93(±0.07) | 98.3(±0.6) | |

| 1.92 | 3.93 | 3.92(±0.04) | 99.7(±0.4) | |

| 2.86 | 4.87 | 4.75(±0.05) | 97.5(±0.5) | |

| D | 0.00 | – | 1.95(±0.01) | – |

| 0.970 | 2.92 | 2.90(±0.04) | 99.3(±0.4) | |

| 1.92 | 3.87 | 3.99(±0.06) | 103(±2) | |

| 2.86 | 4.81 | 4.84(±0.07) | 101(±3) | |

| E | 0.00 | – | 1.92(±0.02) | – |

| 0.970 | 2.89 | 2.93(±0.05) | 101(±3) | |

| 1.92 | 3.84 | 3.92(±0.08) | 102(±4) | |

| 2.86 | 4.78 | 4.81(±0.01) | 101(±0.1) |

Table 4.

Estriol addition-recovery experiment results for urine samples using the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method.

| Human urine sample | [Estriol] added (μmol/L, n = 3) | [Estriol] expected (μmol/L, n = 3) | [Estriol] found (μmol/L, n = 3) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.00 | – | 1.99(±0.12) | – |

| 0.960 | 2.95 | 2.98(±0.09) | 101(±3) | |

| 1.91 | 3.90 | 3.88(±0.06) | 99.6(±1.5) | |

| 2.84 | 4.83 | 4.78(±0.02) | 99.0(±0.2) | |

| B | 0.00 | – | 1.95(±0.05) | – |

| 0.960 | 2.91 | 2.96(±0.04) | 102(±1) | |

| 1.91 | 3.86 | 3.83(±0.06) | 99.2(±0.5) | |

| 2.84 | 4.79 | 4.75(±0.01) | 99.2(±0.1) | |

| C | 0.00 | – | 1.97(±0.08) | – |

| 0.960 | 2.93 | 2.95(±0.05) | 101(±1) | |

| 1.91 | 3.88 | 3.91(±0.03) | 101(±0.6) | |

| 2.84 | 4.81 | 4.75(±0.01) | 98.7(±0.1) | |

| D | 0.00 | – | 2.02(±0.07) | – |

| 0.960 | 2.98 | 2.95(±0.06) | 99.0(±0.4) | |

| 1.91 | 3.93 | 3.89(±0.03) | 99.0(±0.2) | |

| 2.84 | 4.86 | 4.84(±0.08) | 99.6(±0.6) | |

| E | 0.00 | – | 1.91(±0.05) | – |

| 0.960 | 2.87 | 2.93(±0.06) | 102(±2) | |

| 1.91 | 3.82 | 3.85(±0.04) | 101(±1) | |

| 2.84 | 4.75 | 4.77(±0.03) | 100(±1) |

The estriol recovery percentage ranged between (96.7 ± 0.3)% and (103 ± 2)% for pharmaceuticals samples and between (98.7 ± 0.1)% and (102 ± 2)% for human urine samples. This suggests that the Co-poly(Met)/GCE can be effectively used to quantify estriol without interference of the sample matrix. It is noticeably demonstrated that the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method is a feasible, sensitive and good alternative for the determination of estriol in pharmaceutical formulations and human urine.

5. Conclusions

This work described the development and application of a novel electroanalytical approach to the direct determination of estriol using the Co-poly(Met)/GCE as an electrochemical sensor. CV and DPV were applied to study the electrochemical behaviour and quantification of estriol. The DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method provided two linear concentration ranges (0.596–4.76 μmol/L and 5.66–9.90 μmol/L), a limit of detection (3.40 × 10−8 mol/L) similar or better than many previously reported electroanalytical methods for estriol determination, and a good intra-day (RSD = 4.00%, 1.94% and 2.37%, n = 6) and inter-day (RSD = 4.13%, 2.66% and 2.11%, n = 6) repeatability for estriol concentrations of 3.0, 5.0 and 10.0 μmol/L, respectively. The developed DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method was tested for the estriol determination in commercial pharmaceutical tablets and human urine samples. Additionally, the estriol concentrations found in the pharmaceutical tablets were equivalent to those obtained by UV-VIS spectrophotometry (confidence level of 95.0%). Satisfactory recovery results were also obtained in relation to the estriol determination in human urine, indicating that the DPV-Co-poly(Met)/GCE method can be successfully applied to this biological fluid. The Co-poly(Met)/GCE-assisted DPV is a simple, eco-friendly, sensitive, rapid, accurate and precise approach that does not require sophisticated instruments or any separation steps, allowing the estriol quantification without laborious and time-consuming procedures.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank CNPq (454438/2014-1), CAPES, FINEP and FAPEMIG for the financial support to this work and scholarships. The authors also thank the support from LMMA sponsored by FAPEMIG (CEX-112-10), SECTES/MG and RQ-MG (FAPEMIG: CEX-RED-00010-14).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2019.04.001.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rang H.P., Dale M.M., Ritter J.M., Flower R.J., Henderson G. eighth ed. Elsevier Editora Ltda; Rio de Janeiro: 2016. Rang & Dale Farmacologia. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katzenellenbogen B.S. Biology and receptor interactions of estriol and estriol derivatives in vitro and in vivo. J. Steroid Biochem. 1984;20:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(84)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goebelsmann U., Jaffe R.B. Oestriol metabolism in pregnant women. Acta. Endocrinol. (Copenh). 1971;66:679–693. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0660679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaron Y., Cherry M., Kramer R.L. Second-trimester maternal serum marker screening: maternal serum α-fetoprotein, β-human chorionic gonadotropin, estriol, and their various combinations as predictors of pregnancy outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:968–974. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cesarino I., Cincotto F.H., Machado S.A.S. A synergistic combination of reduced graphene oxide and antimony nanoparticles for estriol hormone detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015;210:453–459. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gan P., Compton R.G., Foord J.S. The voltammetry and electroanalysis of some estrogenic compounds at modified diamond electrodes. Electroanalysis. 2013;25:2423–2434. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flor S., Lucangioli S., Contin M. Simultaneous determination of nine endogenous steroids in human urine by polymeric-mixed micelle capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:3305–3313. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X., Roman J.M., Issaq H.J. Quantitative measurement of endogenous estrogens and estrogen metabolites in human serum by liquid Chromatography− tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:7813–7821. doi: 10.1021/ac070494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo T., Gu J., Soldin O.P. Rapid measurement of estrogens and their metabolites in human serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry without derivatization. Clin. Biochem. 2008;41:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X., Spink D.C., Schneider E. Measurement of unconjugated estriol in serum by liquid chromatography- tandem mass spectrometry and assessment of the accuracy of chemiluminescent immunoassays. Clin. Chem. 2014;60:260–268. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.212126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng G.-J., Fang L.-Q., Chen H. Magnetic microparticle chemiluminescence immunoassay method for determination of estriol in human urine. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2012;39:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Y.-P., Zhao S.-Q, Wu Y.-S. A direct competitive inhibition time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay for the detection of unconjugated estriol in serum of pregnant women. Anal. Methods. 2013;5:4068–4073. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrási N., Helenkár A., Vasanits-Zsigrai A. The role of the acquisition methods in the analysis of natural and synthetic steroids and cholic acids by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:8264–8272. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piwowarska J., Radowicki S., Pachecka J. Simultaneous determination of eight estrogens and their metabolites in serum using liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Talanta. 2010;81:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pharmacopeia U.S. US Pharmacopeial Conv. Inc., Rockville, MD. 2006. USP 29; pp. 3281–3282. [Google Scholar]

- 16.XIV J.P. Japan Soc. Japanese Pharmacopeia; 2001. The Japanese Pharmacopeia. [Google Scholar]

- 17.E.D. 5th.ed. Council of Europe; Strasbourg, France: 2004. For the Q. of Medicines, European Pharmacopoeia. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molaakbari E., Mostafavi A., Beitollahi H. Synthesis of ZnO nanorods and their application in the construction of a nanostructure-based electrochemical sensor for determination of levodopa in the presence of carbidopa. Analyst. 2014;139:4356–4364. doi: 10.1039/c4an00138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cincotto F.H., Canevari T.C., Machado S.A.S. Reduced graphene oxide-Sb2O5 hybrid nanomaterial for the design of a laccase-based amperometric biosensor for estriol. Electrochim. Acta. 2015;174:332–339. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferraz B.R.L., Profeti D., Profeti L.P.R. Sensitive detection of sulfanilamide by redox process electroanalysis of oxidation products formed in situ on glassy carbon electrode. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2018;22:339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta V.K., Jain R., Radhapyari K. Voltammetric techniques for the assay of pharmaceuticals-a review. Anal. Biochem. 2011;408:179–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han Q., Shen X., Zhu W. Magnetic sensing film based on Fe3O4@Au-GSH molecularly imprinted polymers for the electrochemical detection of estradiol. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;79:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Florea A., Cristea C., Vocanson F. Electrochemical sensor for the detection of estradiol based on electropolymerized molecularly imprinted polythioaniline film with signal amplification using gold nanoparticles. Electrochem. Commun. 2015;59:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y., Zhao X.R., Li P. Highly sensitive Fe3O4 nanobeads/graphene-based molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor for 17 β-estradiol in water. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2015;884:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang K.J., Liu Y.J., Shi G.W. Label-free aptamer sensor for 17β-estradiol based on vanadium disulfide nanoflowers and Au nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014;201:579–585. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin G.-P., Lin X.-Q. Voltammetric behavior and determination of estrogens at carbamylcholine modified paraffin-impregnated graphite electrode. Electrochim. Acta. 2005;50:3556–3562. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin X., Li Y. A sensitive determination of estrogens with a Pt nano-clusters/multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified glassy carbon electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006;22:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos K.D., Braga O.C., Vieira I.C. Electroanalytical determination of estriol hormone using a boron-doped diamond electrode. Talanta. 2010;80:1999–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochiai L.M., Agustini D., Figueiredo-Filho L.C.S. Electroanalytical thread-device for estriol determination using screen-printed carbon electrodes modified with carbon nanotubes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017;241:978–984. [Google Scholar]

- 30.da Silveira J.P., Piovesan J.V., Spinelli A. Carbon paste electrode modified with ferrimagnetic nanoparticles for voltammetric detection of the hormone estriol. Microchem. J. 2017;133:22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jodar L.V., Santos F.A., Zucolotto V. Electrochemical sensor for estriol hormone detection in biological and environmental samples. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2018;22:1431–1438. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manjunatha J.G. Electroanalysis of estriol hormone using electrochemical sensor. Sens. Biosensing Res. 2017;16:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donini C.A., da Silva M.K.L., Simões R.P. Reduced graphene oxide modified with silver nanoparticles for the electrochemical detection of estriol. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018;809:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J., Zhang J., Lin X. Electrocatalytic oxidation and determination of dopamine in the presence of ascorbic acid and uric acid at a poly (4-(2-pyridylazo)-resorcinol) modified glassy carbon electrode. Electroanalysis. 2007;19:612–615. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou S., Zheng N., Feng H. Determination of dopamine in the presence of ascorbic acid using poly(3,5-dihydroxy benzoic acid) film modified electrode. Anal. Biochem. 2008;381:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta P., Goyal R.N. Sensitive determination of domperidone in biological fluids using a conductive polymer modified glassy carbon electrode. Electrochim. Acta. 2015;151:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehretie S., Admassie S., Hunde T. Simultaneous determination of N-acetyl-p-aminophenol and p-aminophenol with poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) modified glassy carbon electrode. Talanta. 2011;85:1376–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devadas B., Rajkumar M., Chen S.M. Electropolymerization of curcumin on glassy carbon electrode and its electrocatalytic application for the voltammetric determination of epinephrine and p-acetoaminophenol. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2014;116:674–680. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang Z., Li G., Zhang M. Electrochemical sensor based on electro-polymerization of β-cyclodextrin and reduced-graphene oxide on glassy carbon electrode for determination of gatifloxacin. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016;228:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 40.da Silva L.V., Lopes C.B., da Silva W.C. Electropolymerization of ferulic acid on multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified glassy carbon electrode as a versatile platform for NADH, dopamine and epinephrine separate detection. Microchem. J. 2017;133:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferraz B.R.L., Leite F.R.F., Malagutti A.R. Highly sensitive electrocatalytic determination of pyrazinamide using a modified poly(glycine) glassy carbon electrode by square-wave voltammetry. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2016;20:2509–2516. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narayana P.V., Reddy T.M., Gopal P. Electrochemical sensing of paracetamol and its simultaneous resolution in the presence of dopamine and folic acid at a multi-walled carbon nanotubes/poly(glycine) composite modified electrode. Anal. Methods. 2014;6:9459–9468. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y., Liu X., Wei W. Square wave voltammetry for selective detection of dopamine using polyglycine modified carbon ionic liquid electrode. Electroanalysis. 2011;23:2832–2838. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paulo T.F., Diógenes I.C., Abruña H.D. Direct electrochemistry and electrocatalysis of myoglobin immobilized on l-cysteine self-assembled gold electrode. Langmuir. 2011;27:2052–2057. doi: 10.1021/la103505x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferraz B.R.L., Leite F.R.F., Malagutti A.R. Simultaneous determination of ethionamide and pyrazinamide using poly(L-cysteine) film-modified glassy carbon electrode. Talanta. 2016;154:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zi L., Li J., Mao Y. High sensitive determination of theophylline based on gold nanoparticles/l-cysteine/Graphene/Nafion modified electrode. Electrochim. Acta. 2012;78:434–439. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J., Zhang S., Zhang Y. Fabrication of chronocoulometric DNA sensor based on gold nanoparticles/poly (L-lysine) modified glassy carbon electrode. Anal. Biochem. 2010;396:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun W., Zhang Y., Ju X. Electrochemical deoxyribonucleic acid biosensor based on carboxyl functionalized graphene oxide and poly-l-lysine modified electrode for the detection of the gene sequence related to vibrio parahaemolyticus. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;752:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bergamini M.F., Santos D.P., Zanoni M.V.B. Electrochemical behavior and voltammetric determination of pyrazinamide using a poly-histidine modified electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2013;690:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vilian A.T.E., Chen S.M. Simple approach for the immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on poly-L-histidine modified reduced graphene oxide for amperometric determination of dopamine and H2O2. RSC Adv. 2014;4:55867–55876. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma W., Sun D.M. The electrochemical properties of dopamine, epinephrine and their simultaneous determination at a poly (L-methionine) modified electrode. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2007;43:1382–1389. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheemalapati S., Devadas B., Chen S.-M. Highly sensitive and selective determination of pyrazinamide at poly-L-methionine/reduced graphene oxide modified electrode by differential pulse voltammetry in human blood plasma and urine samples. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;418:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ojani R., Alinezhad A., Abedi Z. A highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for simultaneous detection of uric acid, xanthine and hypoxanthine based on poly(L-methionine) modified glassy carbon electrode. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013;188:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gu Y., Yan X., Liu W. Biomimetic sensor based on copper-poly (cysteine) film for the determination of metronidazole. Electrochim. Acta. 2015;152:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheung K.-C., Wong W.-L., Ma D.-L. Transition metal complexes as electrocatalysts-Development and applications in electro-oxidation reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007;251:2367–2385. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ojani R., Raoof J.B., Maleki A.A. Simultaneous and sensitive detection of dopamine and uric acid using a poly(L-methionine)/gold nanoparticle-modified glassy carbon electrode. Chin. J. Catal. 2014;35:423–429. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emami M., Shamsipur M., Saber R. Design of poly-L-methionine-gold nanocomposite/multi-walled carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode for determination of amlodipine in human biological fluids. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2014;18:985–992. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Committee A.M. Recommendations for the definition, estimation and use of the detection limit. Analyst. 1987;112:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masond M.S., El-Hamid O.H.A. Structural chemistry of amino acid complexes. Transit. Met. Chem. 1989;14:233–234. [Google Scholar]

- 60.K'Owino I.O., Sadik O.A. Impedance spectroscopy: a powerful tool for rapid biomolecular screening and cell culture monitoring. Electroanalysis. 2005;17:2101–2113. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bard A.J., Faulkner L.R. second ed. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2001. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bard A.J., Denuault G., Lee C. Scanning electrochemical microscopy: a new technique for the characterization and modification of surfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990;23:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brett C.M.A., Brett A.M.O. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1993. Electrochemistry: Principles, Methods, and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonçalves L.M., Batchelor-Mcauley C., Barros A.A. Electrochemical oxidation of adenine: a mixed adsorption and diffusion response on an edge-plane pyrolytic graphite electrode. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:14213–14219. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Batchelor-McAuley C., Gonçalves L.M., Xiong L. Controlling voltammetric responses by electrode modification; using adsorbed acetone to switch graphite surfaces between adsorptive and diffusive modes. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:9037–9039. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03961f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tavares E.M., Carvalho A.M., Gonçalves L.M. Chemical sensing of chalcones by voltammetry: trans-Chalcone, cardamonin and xanthohumol. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;90:440–444. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Triola M.F. eleventh ed. LTC; Rio de Janeiro: 2013. Introdução à Estatística. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.