Abstract

Introduction:

Rural-urban differences in cigarette and cannabis use have traditionally shown higher levels of cigarette smoking in rural areas and of cannabis use in urban areas. To assess for changes in this pattern of use, we examined trends and prevalence of cigarette, cannabis, and co-use across urban-rural localities.

Methods:

Urban-rural trends in current cigarette and/or cannabis use was evaluated using 11 cohorts (2007–2017) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH; N=397,542). We used logistic regressions to model cigarette and cannabis use over time, adjusting for demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, education), in addition to assessing patterns of cannabis use among cigarette smokers and nonsmokers.

Results:

Despite decreases in cigarette smoking overall, between 2007 and 2017, the urban-rural disparity in cigarette smoking increased (AOR=1.17), with less reduction in rural as compared to urban cigarette smokers. Cannabis use increased in general (AOR=1.88 by 2017), with greater odds in urban than rural regions. Cannabis use increased more rapidly in non-cigarette smokers than smokers (AOR=1.37 by 2017), with 219% greater odds of cannabis use in rural non-cigarette smokers in 2017 versus 2007.

Conclusions:

Rurality remains an important risk factor for cigarette smoking in adults and the fastest-growing group of cannabis users is rural non-cigarette smokers; however, cannabis use is currently still more prevalent in urban areas. Improved reach and access to empirically-supported prevention and treatment, especially in rural areas, along with dissemination and enforcement of policy-level regulations, may mitigate disparities in cigarette use and slow the increase in rural cannabis use.

Keywords: Cigarette, cannabis, urban, rural, geographic disparity, NSDUH

1.1. Introduction

Despite extensive reductions over the past five decades in cigarette smoking in the United States (US), tobacco use continues to be the leading preventable cause of death (Fenelon and Preston, 2012; Jha et al., 2013; Reitsma et al., 2017), with cigarettes being the most commonly used tobacco product (Hu et al., 2016). Prior work has documented geographic differences in the prevalence of cigarette smoking with higher rates in rural areas, especially the rural South and Midwest, even after accounting for socioeconomic status (Matthews et al., 2017). Moreover, recent work indicates that reductions in cigarette smoking are disproportionately due to reductions in smoking in urban regions and less so to declines in rural areas (Doogan et al. 2017), raising the question of whether urban-rural geographic disparities will become more pronounced over time.

Cannabis is the most commonly used Schedule 1 drug in the US and the majority of those who use cannabis also smoke cigarettes (Leatherdale et al., 2006; Richter et al., 2005; SAMHSA, 2013). Increases in cannabis use over the past two decades have coincided with reductions in perceived risk of use and state-level policies expanding medical and recreational access (Hasin et al., 2017; Martins et al., 2016; Okaneku et al., 2015; Pacek et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2015). With regard to co-use (i.e., current use of cigarettes and cannabis), cannabis use among tobacco users is increasing; whereas, tobacco use among cannabis users is on the decline (Schauer et al., 2015). However, the interplay between the rapidly changing cigarette and cannabis use landscapes across urban and rural regions is not well understood.

Our primary aim is to describe the changing trends from 2007–2017 in adults’ cigarette smoking, cannabis use, and co-use across urban and rural regions using the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Informed by prior findings, we hypothesized 1) higher prevalence of cigarettes use in rural areas and cannabis use in urban areas (Hasin et al., 2019; Matthews et al., 2017), 2) greater decreases in cigarette use in urban compared to rural areas (Doogan et al., 2017), 3) greater increases in cannabis use in urban than rural areas (Hasin et al., 2019), and 4) the greatest increase in cannabis use among urban cigarette smokers (Hasin et al., 2019; Schauer et al., 2015).

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Study Population

The dataset included those 18 years and older from the last 11 years (2007–2017) of the NSDUH, which are annual, cross-sectional surveys of non-institutionalized individuals in the 50 US states and the District of Columbia (SAMHSA, 2013). Each year, a nationally-representative multistage probability sample of household-dwelling individuals in the US is obtained. We used the NSDUH sampling weights to ensure that estimates were consistent with those provided by the US Census Bureau. Additional information on survey methods and sampling techniques can be found elsewhere (“National Survey on Drug Use and Health”).

2.1.2. Measures

The dependent variables were current cigarette smoking and current cannabis use as defined as consumption of at least one cigarette or use of cannabis (termed in the NSDUH as marijuana or hashish) in the past 30 days, respectively. Current co-use was defined as use of both cigarettes and cannabis within the past 30 days. The primary independent variables were geographic locality and year (NSDUH survey year). Geographic locality was determined using the Office of Management and Budget Rural-Urban Continuum Codes which provide county-level designation based on urbanization and adjacency to metro areas. The 2007–2014 surveys based urban/rural designation on the 2003 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes and 2015–2017 surveys used the updated 2013 codes. Those counties that did not include metro or micropolitan statistical areas and those that included labor market areas with fewer than 50,000 people were defined as rural. Year was an integer variable ranging from 2007 to 2017 with 2007 as the reference year. Age, race/ethnicity, income, education, and gender were included as covariates in all models. Age (18–34, 35–49, and 50+ year olds), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other), income (<$20,000, $20,000-$49,999, $50,000-$74,999, >$74,999), education (some high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), and gender (female, male) were each coded categorically.

2.1.3. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), via the SURVYEYFREQ and SURVEYLOGISTIC procedures which utilized the NSDUH-derived weight, stratum, and cluster variables. Logistic regressions, adjusted for age group, gender, income, education, and race/ethnicity, were conducted to estimate the odds of current cigarette smoking and cannabis use overall and by locality for the 2007–2017 period. Interactions between year and geographic locality were entered alongside main effects into each model and preserved in the model if significant. To assess the relationship between cigarette and cannabis co-use, current smoking status along with an interaction term for smoking status and locality were subsequently added to the model predicting current cannabis use.

3.1. Results

3.1.1. Descriptive results

The overall weighted sample (N=397,542) was composed of 16% rurally-designated respondents. Sample characteristics across cohorts are presented in the Supplementary Materials Table 1. In general, rural compared to urban individuals were older (p<0.001), in a lower income bracket (p<0.001), and completed less formal education (p<0.001). Both urban and rural subsamples had more females (52%) than males and the rural subsample comprised a higher proportion of non-Hispanic White individuals than the urban subsample (p<0.001).

3.1.2. Cigarette use

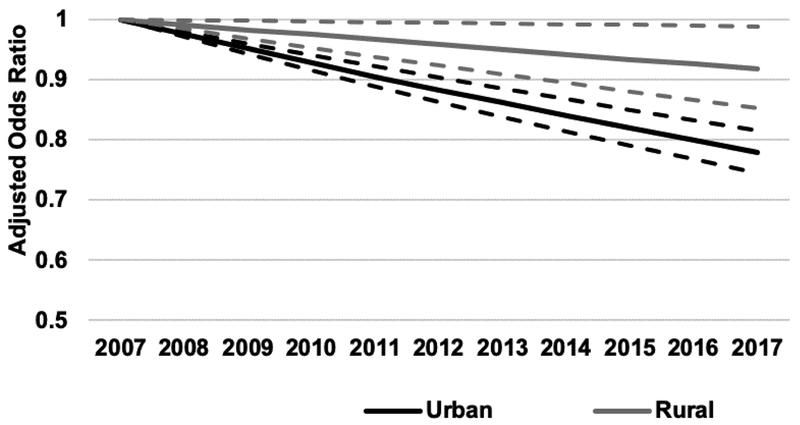

Observed prevalence of current cigarette smoking declined from 25.8% in 2007 to 19.4% in 2017 (see Supplementary Table 2). In adjusted models, percentage of persons with current cigarette use decreased more slowly in rural areas as compared to urban (p<0.005). In 2017, persons in urban areas had 15% lower odds (AOR=0.85; 95% CI: 0.81–0.88; p<0.005) of smoking cigarettes than in 2007. By comparison, persons in rural areas had only 8% lower odds of smoking cigarettes in 2017 than they had in 2007 (AOR=0.92; 95% CI: 0.85–0.99; p<0.05). By 2017, rural individuals had 18% greater odds of current cigarette smoking than urban individuals, after adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, income, education, and gender (AOR=1.18; 95% CI=1.14–1.21). The more rapid decline in urban than rural regions enhanced the urban-rural geographic disparity in cigarette smoking prevalence over the past decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Urban and rural changes in cigarette smoking from 2007–2017.

Adjusted odds ratios (solid lines) and 95% confidence intervals (dotted lines) of current cigarette smoking relative to 2007 by geographic locality.

3.1.3. Cannabis use

In 2007, an estimated 5.6% of the adult population reported current cannabis use; by 2017, the observed prevalence had nearly doubled to 9.5% (see Supplementary Table 2). In adjusted effects models, the prevalence of current cannabis use increased linearly with year; by 2017, the adjusted odds of current cannabis use were 1.94 times greater than in 2007 (AOR=1.94; 95% CI: 1.84–2.04; p<0.005). Over the surveyed period, those in rural areas had lower odds of having used cannabis in the past 30 days compared to urban individuals (AOR=0.71; 95% CI: 0.68–0.75; p<0.005). We then examined whether the change in prevalence of cannabis use differed by geographic locality, and found that the difference in the rate of change between urban and rural cannabis use from 2007 to 2017 was not significant (p=0.08, ns).

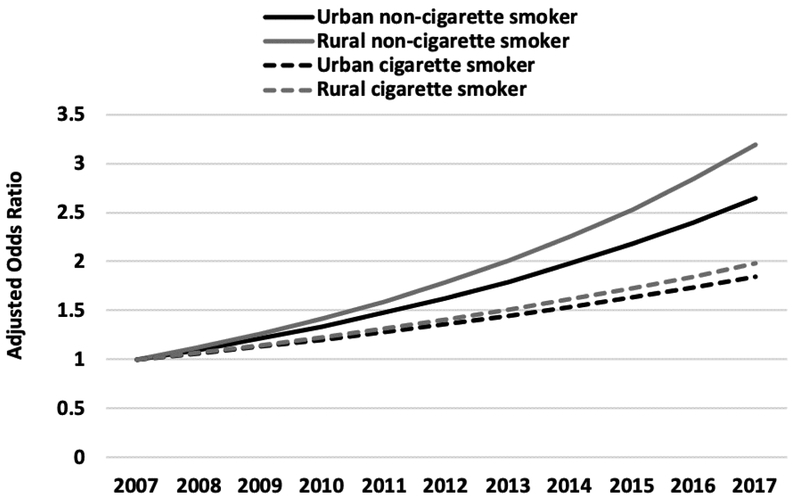

3.1.4. Cigarette and cannabis co-use

In 2017, 47.5% (95% CI: 45.6, 49.4; observed prevalence) of cannabis users reported current cigarette smoking compared to 66.4% (95% CI: 63.4–69.3; observed prevalence) in 2007 (see Supplementary Table 2). We added current cigarette smoking status and the interaction of smoking with year to the model to examine whether current cannabis use was moderated by concurrent cigarette use. The odds of cannabis use increased more rapidly among non-cigarette smokers than smokers (AOR=1.37, 95% CI: 1.24–1.50, p<0.005; see Figure 2). Relative to 2007, cigarette smokers had 87% greater odds of using cannabis by 2017 (AOR=1.87; 95% CI: 1.75–2.00, p<0.005); whereas, non-cigarette smokers had 124% greater odds of currently using (AOR=2.24; 95% CI: 2.12–2.36, p<0.005). Across both cigarette smokers and nonsmokers, the greatest increase in relative odds of cannabis use was among rural non-cigarette smokers who had 219% greater odds of using cannabis in 2017 than in 2007 (AOR=3.19; 95% CI: 2.56–3.98).

Figure 2. Changes in cannabis use from 2007 to 2017 by locality and smoking status.

Change in adjusted odds of current cannabis use by urban (black) and rural (grey) locality and smoking status (smoker=dotted, nonsmoker=solid) relative to 2007.

4.1. Discussion

Three primary findings emerged from this national study of US adults. First, the geographic disparity in cigarette smoking is increasing over time with a slower decline in cigarette use in rural versus urban cigarette smokers. Second, cannabis use is increasing in both urban and rural areas, with consistently higher prevalence in urban populations. Third, cannabis users are no longer predominantly concurrent cigarette smokers, with the prevalence of cannabis use increasing most rapidly in rural non-cigarette smokers.

Higher risk of cigarette smoking in rural regions is likely due to multiple factors including lower perceptions of risk of smoking (Weinstein et al., 2005), less access to prevention and cessation treatments (Carlson et al., 2012; Hutcheson et al., 2008), and more lenient tobacco control policies (York et al., 2010). Ongoing and future initiatives to increase access and reach of empirically-supported tobacco cessation treatments in the rural US may help to mitigate these disparities. Additionally, increased implementation and enforcement of tobacco control policies (e.g., increased tax rates, clean air laws) in rural areas may reduce disparities for vulnerable rural residents.

As hypothesized, the prevalence of current cannabis use is increasing across the US and is more prevalent in urban than rural regions with 9.8% of urban individuals reporting current cannabis use compared to 8.2% of rural individuals in 2017. Some of the largest urban areas are in states with the earliest changes in laws related to medical and/or recreational cannabis, which may be partially driving early increases in these urban areas (Hasin et al. 2019). Contrary to past findings that the majority of cannabis users are tobacco smokers, by 2017, only 47.5% of cannabis users also reported concurrent cigarette smoking. The reduction in prevalence of current cigarette smokers along with the rapidly increasing prevalence of cannabis use by non-cigarette smokers points to a forthcoming change in the tobacco and cannabis landscape.

Unexpectedly, the prevalence of current cannabis use is increasing more rapidly among non-cigarette smokers than smokers, which may be due, in part, to fewer Americans smoking cigarettes (Keyes et al., 2019; Kulik and Glantz, 2016). An additional possibility is that the increasing availability of cannabis products designed for other routes of administration (e.g., edible, vaped, etc.) may be leading to greater cannabis utilization in nonsmokers. In addition to increasing rates of cannabis use among non-cigarette smokers in general, the greatest demographic adjusted increase from 2007 to 2017 was among rural non-cigarette smokers (219%), followed by urban non-cigarette smokers (165%), rural cigarette smokers (98%), and urban cigarette smokers (85%). If this pattern persists, living in rural regions may become a risk factor for cannabis use. Targeted education, prevention, and treatment services may diminish the increases in cannabis use in rural areas. These interventions can be facilitated through the increased reach and acceptability of digital media and telehealth options in more remote parts of the US.

Limitations of the current study include that the analyses were restricted to conventional cigarettes, other tobacco and nicotine products (e.g., e-cigarettes) may show different patterns of use with regard to geographic locality and cannabis use. Second, the measures of cigarette use, cannabis use, and co-use in the NSDUH were selected to have comparable questions to define current use (i.e., past 30-day use). This measure does not include an estimate of the amount, frequency, or duration of use which could help to further define the inter-relationship between urban and rural use of cannabis and cigarettes. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the NSDUH precludes the examination of change in individual patterns of use, limiting the ability to differentiate between changes in cessation, initiation, and co-use of cannabis and cigarettes. Future investigations looking at moderators of effects, including demographic characteristics, and using longitudinal data are needed to more fully depict the potential public health impact of changes in urban and rural use of cannabis and cigarettes, to target specific subpopulations at the highest risk, and to determine what prevention and treatment strategies are likely to be most impactful.

In conclusion, living in a rural area continues to be a risk factor for cigarette smoking; whereas current cannabis use is more prevalent in urban areas and is increasingly common among non-cigarette smokers, with the fastest growth among rural non-cigarette smokers. The combination of higher prevalence of cigarette smoking in rural areas and the most rapid increases in cannabis use in rural non-cigarette smokers emphasizing a growing need to improve reach and access to empirically supported prevention and treatment in rural regions in addition to uniform dissemination and enforcement of policy-level regulations.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cigarette and cannabis use in adults is changing across rural and urban America.

Rural geographic disparities in cigarette smoking are increasingly pronounced.

Cannabis use increased the most in rural non-cigarette smokers.

Cannabis users are no longer predominantly cigarette smokers.

Role of Funding Source:

Dr. Coughlin’s time was supported by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (T32AA007477). Dr. Bohnert is supported by Career Development Award (CDA) from the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service (11-245).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Carlson LE, Lounsberry JJ, Maciejewski O, Wright K, Collacutt V, Taenzer P, 2012. Telehealth-delivered group smoking cessation for rural and urban participants: feasibility and cessation rates. Addict. Behav 37, 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doogan NJ, Roberts ME, Wewers ME, Stanton CA, Keith DR, Gaalema DE, Kurti AN, Redner R, Cepeda-Benito A, Bunn JY, Lopez AA, Higgins ST, 2017. A growing geographic disparity: Rural and urban cigarette smoking trends in the United States. Prev. Med 104, 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon A, Preston SH, 2012. Estimating smoking-attributable mortality in the United States. Demography 49, 797–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Stohl M, Galea S, Wall MM, 2017. US Adult Illicit Cannabis Use, Cannabis Use Disorder, and Medical Marijuana Laws. JAMA Psychiatry. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL, 2019. Time trends in US cannabis use and cannabis use disorders overall and by sociodemographic subgroups: a narrative review and new findings. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SS, Sean Hu S, Neff L, Agaku IT, Cox S, Day HR, Holder-Hayes E, King BA, 2016. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2013–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6527a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson TD, Allen Greiner K, Ellerbeck EF, Jeffries SK, Mussulman LM, Casey GN, 2008. Understanding Smoking Cessation in Rural Communities. The Journal of Rural Health 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, McAfee T, Peto R, 2013. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med 368, 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Rutherford C, Miech R, 2019. Historical trends in the grade of onset and sequence of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use among adolescents from 1976–2016: Implications for “Gateway” …. Drug Alcohol Depend. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik MC, Glantz SA, 2016. The smoking population in the USA and EU is softening not hardening. Tob. Control 25, 470–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST, Ahmed R, Kaiserman M, 2006. Marijuana use by tobacco smokers and nonsmokers: who is smoking what? CMAJ 174, 1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Mauro CM, Santaella-Tenorio J, Kim JH, Cerda M, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Galea S, Wall M, 2016. State-level medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived availability of marijuana among the general U.S. population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Kanny D, Wheaton AG, Cunningham TJ, Khan LK, Caraballo RS, Holt JB, Eke PI, Giles WH, 2017. Health-Related Behaviors by Urban-Rural County Classification - United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill. Summ 66, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health [WWW Document], n.d. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. URL https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health (accessed 5.29.19).

- Okaneku J, Vearrier D, McKeever RG, LaSala GS, Greenberg MI, 2015. Change in perceived risk associated with marijuana use in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Clin. Toxicol 53, 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Mauro PM, Martins SS, 2015. Perceived risk of regular cannabis use in the United States from 2002 to 2012: differences by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 149, 232–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsma MB, Fullman N, Ng M, Salama JS, Abajobir A, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abera SF, Abraham B, Abyu GY, Adebiyi AO, Al-Aly Z, Aleman AV, Ali R, Al Alkerwi A. ‘a, Allebeck P, Al-Raddadi RM, Amare AT, Amberbir A, Ammar W, Amrock SM, Antonio CAT, Asayesh H, Atnafu NT, Azzopardi P, Banerjee A, Barac A, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Basto-Abreu AC, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Bedi N, Bell B, Bello AK, Bensenor IM, Beyene AS, Bhala N, Biryukov S, Bolt K, Brenner H, Butt Z, Cavalleri F, Cercy K, Chen H, Christopher DJ, Ciobanu LG, Colistro V, Colomar M, Cornaby L, Dai X, Damtew SA, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dansereau E, Davletov K, Dayama A, Degfie TT, Deribew A, Dharmaratne SD, Dimtsu BD, Doyle KE, Endries AY, Ermakov SP, Estep K, Faraon EJA, Farzadfar F, Feigin VL, Feigl AB, Fischer F, Friedman J, G/hiwot TT, Gall SL, Gao W, Gillum RF, Gold AL, Gopalani SV, Gotay CC, Gupta R, Gupta R, Gupta V, Hamadeh RR, Hankey G, Harb HL, Hay SI, Horino M, Horita N, Hosgood HD, Husseini A, Ileanu BV, Islami F, Jiang G, Jiang Y, Jonas JB, Kabir Z, Kamal R, Kasaeian A, Kesavachandran CN, Khader YS, Khalil I, Khang Y-H, Khera S, Khubchandani J, Kim D, Kim YJ, Kimokoti RW, Kinfu Y, Knibbs LD, Kokubo Y, Kolte D, Kopec J, Kosen S, Kotsakis GA, Koul PA, Koyanagi A, Krohn KJ, Krueger H, Defo BK, Bicer BK, Kulkarni C, Kumar GA, Leasher JL, Lee A, Leinsalu M, Li T, Linn S, Liu P, Liu S, Lo L-T, Lopez AD, Ma S, El Razek HMA, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Manamo WA, Martinez-Raga J, Mekonnen AB, Mendoza W, Miller TR, Mohammad KA, Morawska L, Musa KI, Nagel G, Neupane SP, Nguyen Q, Nguyen G, Oh I-H, Oyekale AS, Pa M, Pana A, Park E-K, Patil ST, Patton GC, Pedro J, Qorbani M, Rafay A, Rahman M, Rai RK, Ram U, Ranabhat CL, Refaat AH, Reinig N, Roba HS, Rodriguez A, Roman Y, Roth G, Roy A, Sagar R, Salomon JA, Sanabria J, de Souza Santos I, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sawyer S, Saylan M, Schaub MP, Schluger N, Schutte AE, Sepanlou SG, Serdar B, Shaikh MA, She J, Shin M-J, Shiri R, Shishani K, Shiue I, Sigfusdottir ID, Silverberg JI, Singh J, Singh V, Slepak EL, Soneji S, Soriano JB, Soshnikov S, Sreeramareddy CT, Stein DJ, Stranges S, Subart ML, Swaminathan S, Szoeke CEI, Tefera WM, Topor-Madry R, Tran B, Tsilimparis N, Tymeson H, Ukwaja KN, Updike R, Uthman OA, Violante FS, Vladimirov SK, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Weiderpass E, Wen C-P, Werdecker A, Wilson S, Wubshet M, Xiao L, Yakob B, Yano Y, Ye P, Yonemoto N, Yoon S-J, Younis MZ, Yu C, Zaidi Z, El Sayed Zaki M, Zhang AL, Zipkin B, Murray CJL, Forouzanfar MH, Gakidou E, 2017. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1885–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Kaur H, Resnicow K, Nazir N, Mosier MC, Ahluwalia JS, 2005. Cigarette Smoking Among Marijuana Users in the United States. Substance Abuse 10.1300/j465v25n02_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, 2013. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H46 (No. HHS Publication no. (SMA) 13–4795). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, Windle M, 2015. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: Trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003–2012. Addict. Behav 49, 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND, Marcus SE, Moser RP, 2005. Smokers’ unrealistic optimism about their risk. Tob. Control 14, 55–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Cummings JR, 2015. The effect of medical marijuana laws on adolescent and adult use of marijuana, alcohol, and other substances. J. Health Econ 42, 64–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York NL, Rayens MK, Zhang M, Jones LG, Casey BR, Hahn EJ, 2010. Strength of tobacco control in rural communities. J. Rural Health 26, 120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.