Abstract

Objectives

Growing recognition that health is shaped by social and economic circumstances has resulted in a rapidly expanding set of clinical activities related to identifying, diagnosing, and intervening around patients’ social risks in the context of health care delivery. The objective of this exploratory analysis was to identify existing documentation tools in common US medical coding systems reflecting these emerging clinical practices to improve patients’ social health.

Materials and Methods

We identified 20 social determinants of health (SDH)-related domains used in 6 published social health assessment tools. We then used medical vocabulary search engines to conduct three independent searches for codes related to these 20 domains included in common medical coding systems (LOINC, SNOMED CT, ICD-10-CM, and CPT). Each of the 3 searches focused on one of three clinical activities: Screening, Assessment/Diagnosis, and Treatment/Intervention.

Results

We found at least 1 social Screening code for 18 of the 20 SDH domains, 686 social risk Assessment/Diagnosis codes, and 243 Treatment/Intervention codes. Fourteen SDH domains (70%) had codes across all 3 clinical activity areas.

Discussion

Our exploratory analysis revealed 1095 existing codes in common medical coding vocabularies that can facilitate documentation of social health-related clinical activities. Despite a large absolute number of codes, there are addressable gaps in the capacity of current medical vocabularies to document specific social risk factor screening, diagnosis, and interventions activities.

Conclusions

Findings from this analysis should help inform efforts both to develop a comprehensive set of SDH codes and ultimately to improve documentation of SDH-related activities in clinical settings.

Keywords: social determinants of health, LOINC, SNOMED CT, International Classification of Diseases

Introduction

A growing literature substantiates the health impacts of social and economic factors related to housing, food, employment, educational attainment, income, and neighborhood safety.1–5 Together with recognition of the cost and quality deficiencies of the US health care system,6–8 the evidence that social risks shape health has contributed to increased interest around identifying key social determinants of health (SDH) and addressing actionable social and economic needs through the health care delivery system. Major professional groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics,9 the American Academy of Family Physicians,10 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,11 and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,12 have issued calls for health care systems to collect and act on patients’ social risk information. This has led to multiple clinical innovations, including a wide range of social needs screening tools and practice-based interventions.13–15 Emerging evidence suggests some of these initiatives can reduce social risks, improve health outcomes, and generate cost savings.16

Making interoperable data available on specific social risks and related clinical interventions could influence care for individual patients by enabling point-of-care data exchange among involved clinical and social services providers.17 At the panel or practice level, social data aggregation across different sites could be used to improve population health management, including documenting social needs within a patient population, implementing and evaluating interventions to address these needs, and using social risk data to refine care delivery models.18 Information on social risks could also be used to compensate health systems serving socially complex populations, whether through risk-adjusted capitation or via direct reimbursement or incentives for care that addresses social needs.19 These data also could support community-level health improvement efforts by enabling health care institutions to contribute to community-level data aggregation and exchange with social service providers, public health departments, and other nonprofit and government partners with shared interests in identifying, improving, and tracking SDH-related needs.20 Finally, information on social risks could strengthen research on interventions undertaken to mitigate their health impacts.17

Each of these uses could be facilitated by systematically collected, standardized, interoperable data on patients’ social risks, and interventions to respond to identified needs. Yet SDH-related needs are rarely captured in clinical documentation systems.21–23 The inconsistency between ideal state and current practice helps to explain the growing interest at federal and state levels about how to make related SDH data more readily available. Several expert groups, including the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)17 and the National Quality Forum19 have noted that a lack of standardized, interoperable terminology for social risk data collected, and acted on in health care settings remains an obstacle to both scaling and studying social risk-related initiatives. In one previous effort to incorporate standardized social data into electronic health records (EHRs), the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) 2015 Edition Health IT Certification Criteria final rule included an optional Social, Psychological, Behavioral criterion for EHR vendors to add coding capacity for NAM’s Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures.24,25 Other nonfederally sponsored initiatives also have contributed to developing coding standards for specific social risk screening tools and interventions.26,27

Prior analyses have found health IT standards vary in their capacity to capture information about specific social needs, for example housing28 and occupation.29,30 These previous studies largely focused on how to capture specific EHR-based social risk data for research purposes. To our knowledge, no analysis to date has characterized the current capacity of health IT vocabulary systems to document the breadth of SDH clinically relevant activities (including activities related to social needs screening, social risk diagnoses, and related treatment) across multiple SDH domains. To guide future efforts toward generating comprehensive social risk health IT standards, we conducted an exploratory analysis of codes currently available across four major terminology systems for the set of SDH domains included in common social health screening tools.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic search of four of the most commonly used medical vocabulary systems (SNOMED CT, ICD-10-CM, LOINC®, and CPT®) in the US to identify screening, assessment, and intervention codes that could be used to document actual clinical practices related to social health activities. Since the focus of this study was on identifying existing codes that could be applied to current clinical practice activities, we included ICD-10-CM rather than ICD-11. Although ICD-11 was released internationally in 2018, the earliest that US practices will transition to ICD-11 is 2022.31 Furthermore, the focus of this study was on outpatient settings so we did not include ICD-PCS. Terminology standards related to vaccines, radiology, and pharmacology were considered unlikely to be relevant to SDH clinical activities and therefore also excluded from the search strategy.32 Though there may be other SDH-relevant codes in newer terminology standards (eg Ontology of Medically Related Social Entities33), we focused this preliminary work on more common terminologies relevant to US practice settings.

Selection of SDH domains

We identified 20 SDH domains covered in six of the most widely used SDH screening tools in the US (Table 1), including: (1) the NAM’s 2014 Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures report, which is the basis for the ONC Social, Psychological, and Behavioral data certification criterion for EHRs17; (2) the National Association of Community Health Center’s PRAPARE survey34; (3) the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s Accountable Health Communities (AHC) survey35; (4) the Health Leads questionnaire36; (5) the University of Maryland’s SEEK tool37; and (6) the WE CARE survey.38 We excluded behavioral and mental health domains covered in the multidomain instruments since this study was focused on the availability of codes related to social and economic risk factors.

Table 1.

| Access to health care |

| Child care |

| Clothing |

| Education |

| Employment |

| Finances |

| Income/poverty |

| Financial stress |

| Food |

| Housing |

| Housing instability/insecurity |

| Housing quality |

| Immigration/migration |

| Incarceration |

| Primary language |

| Race/ethnicity |

| Residential address |

| Safety |

| Intimate partner violence |

| Child abuse |

| Neighborhood safety |

| Social connections/isolation |

| Stress |

| Transportation |

| Utilities |

| Veteran status |

| General SDH (not domain-specific) |

For three SDH domains identified in these tools (finances, housing, safety), we itemized subdomains that had different implications for assessment and treatment within a broader parent domain. In these cases, we added search terms specific to those subdomains, though search results were included under the parent domain.

SDH-related clinical activities

Across SDH domains, we searched for codes related to specific clinical activities (Screening, Assessment/Diagnosis, and Treatment/Intervention),26 since different types of SDH information are generated during different clinical activities.13,39–48

SDH Screening: This category includes codes both for individual screening questions and codes for panels of screening questions, as well as codes that report whether screening procedures have been performed;

SDH Assessment/Diagnosis: Codes that capture provider assessment or diagnosis of social needs, whether based on provider interpretation of social screening results or other information;

SDH Treatment/Intervention: Codes that summarize actions undertaken to help address identified social needs. These were subdivided into Referrals, Education/Counseling, and Provision of Services/Orders.

Medical vocabulary search

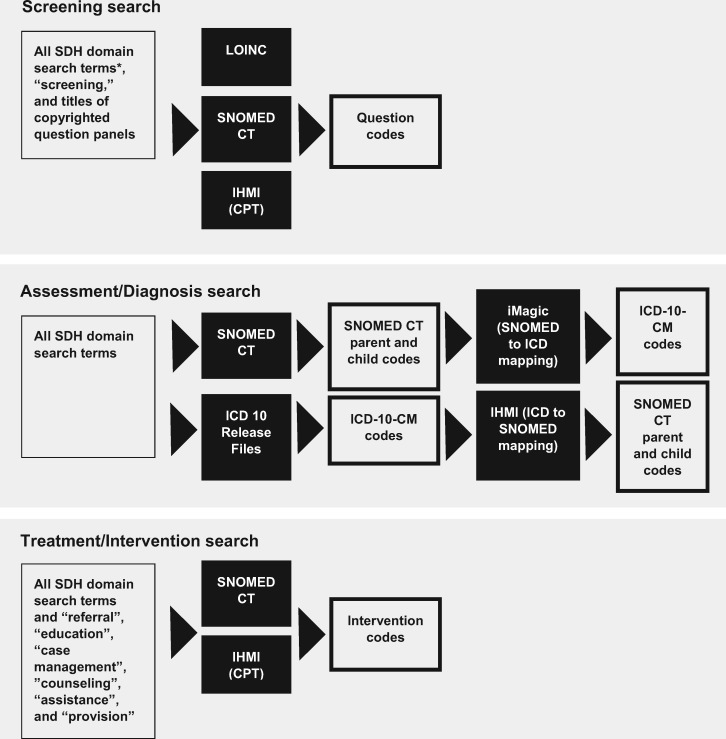

After identifying the SDH domains, two authors (A.A., S.D.) conducted three searches, each dedicated to one of the three clinical activities: Screening, Assessment/Diagnosis, and Treatment/Intervention. The systematic, multidatabase searches included the LOINC database,49 the US version of the SNOMED CT browser,50 the National Center for Health Statistics’ 2018 ICD-10-CM release files,51 and the American Medical Association’s Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) search tool for CPT codes,52 and were conducted between August 1, 2017 and March 1, 2018. A set of search terms (see Supplementary Table S1) was used for each search, with additional terms included in specific searches as described below and shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram of database search processes for screening, assessment/diagnosis, and treatment/interventions categories. *“All SDH domain search terms” refers to the set of search terms described in Supplementary Table S1, which was used in all three searches. Black boxes refer to databases that were searched.

The search terms were compiled based on the SDH domain names, terms used in the 6 screening tools, an open internet search for terms related to each SDH domain, a CPT resource developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, and additional search terms recommended by analysts from the 4 standards development organizations.53 We included “General (nonspecific)” codes, which we searched for using terms related to more overarching social health topics (eg “social determinants of health”). For each search, identified codes were included if both reviewing authors agreed the code was relevant to the selected SDH domain. If codes were relevant to social needs in general, but not domain-specific, codes were moved to the General SDH category.

For the Screening search, the LOINC, SNOMED CT, and IHMI (for CPT) databases were queried using all search terms, and the additional term “screening.” We added search terms for titled question panels from AHC, NAM, and Health Leads questionnaires. In LOINC and SNOMED, in cases where questions are part of a larger question panel, the whole panel has one code; each individual question has a code; and all answers have codes. We included only the panel codes in our results. When items were not part of a panel, we included specific question codes.

For the Assessment/Diagnosis search, we queried the SNOMED CT database using all search terms. For each result, we then used embedded SNOMED CT relationship logic to find the highest domain-specific concept in the hierarchy, “the parent,” and followed this relationship logic to include all associated, relevant child codes. Next, we searched the ICD-10-CM release files (via Adobe Reader pdf search) for all search terms. We again followed established relationship logic to include relevant parent and child codes. We then used two tools to find related, mapped codes for each search result: the National Library of Medicine’s iMAGIC tool54 for SNOMED CT to ICD-10-CM maps and the IHMI tool for bidirectional maps. All domain-specific, mapped parent and child codes were included in results. Since no external cause codes can be primary codes at the point of diagnosis, ICD-10-CM external cause codes (V-Y) were excluded.

For the Treatment/Intervention search, the SNOMED CT and IHMI (CPT) databases were queried using all search terms and the additional intervention terms “referral,” “education,” “case management,” “counseling,” “assistance,” and “provision.” These results were then subdivided into the following categories: Referral, Counseling/Education, and Provision of Services/Orders codes.

RESULTS

We found 133 Screening question or screening panel codes, 33 Screening procedure codes, 686 Assessment/Diagnosis codes, and 243 Treatment/Intervention codes across LOINC, SNOMED CT, ICD-10-CM, and CPT (Table 2). All identified codes are available online so that they can be updated as new codes are developed.55 Below we present an analysis of the identified codes and coding gaps.

Table 2.

Total numbers of codes resulting from the three multidatabase searches

| Domain/Subdomain | Social screening |

Social assessment/diagnosis |

Social treatment/intervention |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOINC questions, question panels/protocol codes | SNOMED CT questions, question panels/protocol codes | SNOMED CT procedure codes | SNOMED CT parent codes | SNOMED CT child codes | ICD-10-CM codes | SNOMED CT referral codes | SNOMED CT counseling/education codes | SNOMED CT provision of services codes | |

| Access to health care | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Child care | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Clothing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Education | 6 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 35 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Employment | 4 | 7 | 1 | 16 | 59 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 10 |

| Finances | 6 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 27 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Income/poverty | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 21 | 2 | |||

| Financial stress | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 0 | |||

| Food | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Housing | 9 | 4 | 2 | 18 | 52 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 16 |

| Instability/insecurity | 7 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 25 | ||||

| Quality | 2 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 27 | ||||

| Immigration/migration | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Incarceration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Primary language | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Race/ethnicity | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Residential address | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Safety | 8 | 5 | 10 | 32 | 88 | 58 | 3 | 16 | 15 |

| General safety (type not specified) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 19 | 23 | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| Child abuse | 1 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 24 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Intimate partner violence | 4 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 35 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Neighborhood safety | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Social connections/isolation | 13 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 34 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 13 |

| Stress | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 18 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 15 |

| Transportation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Utilities | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Veteran status | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 23 | 18 | 14 | 5 |

| CPT codes | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 1 |

| Totals | |||||||||

| Total number of codes | 133 | 33 | 686 | 243 | |||||

| Mean number codes per domain (SD) | 6.7 (5.6) | 1.6 (2.6) | 6.4 (8.1) | 21.3 (22.7) | 6.7 (13.2) | 11.5 (11.3) | |||

Gray indicates subdomains, for which codes are counted in the parent domain (for totals and means). In cases where a subdomain is blank (eg Treatment/Intervention codes for Housing and Finances), codes found did not specify subdomain. CPT codes are listed separately because there were so few and only one was domain-specific (Transportation). Since external cause codes can be primary codes at the point of diagnosis, ICD-10-CM external cause codes (V-Y) are not included in these results, but interested readers can find the numbers the external cause codes in Supplementary Table S2. Readers can review the actual codes in each category by visiting http://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/mmi/compendium-medical-terminology-codes-social-risk-factors.

Distribution of codes across activities and domains

Every SDH domain was represented in at least 1 clinical activity area and the majority of domains (70%, n = 14) had codes in all 3 clinical activity areas. Five domains (Child care, Clothing, Incarceration, Immigration/Migration, and Veteran status) lacked codes in 1 activity area. One domain (Residential Address) had only codes related to Screening. Domains with particularly high numbers of codes (number of codes above the mean in every clinical activity) were Education, Employment, Housing, Safety, and Social Connections/Isolation.

Screening codes

The majority of SDH domains (90%, n = 18) were coded in 1 or more screening panels or independent screening questions. The actual questions used in the 6 social screening tools, however, were not consistently encoded verbatim. Screens that incorporated validated question panels were more likely to be encoded. For instance, though every domain included in the NAM tool had a corresponding LOINC or SNOMED CT-coded question panel (meaning the questions were validated, copyrighted measures), none of the SEEK or WECARE items had a code corresponding to the specific questions used in that instrument. The questions in the remaining three tools were partially coded in LOINC and SNOMED CT (range 25% to 38% of domains with a coded question panel). Table 3 summarizes the availability of Screening codes in relation to the question panels used in the 6 screening tools.

Table 3.

Availability of screening codes corresponding to specific questions of six screening tools

| Domain | Subdomain | LOINC/SNOMED CT codes for question panels used in screening tools |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHC | Health Leads | NAM | PRAPARE | SEEK | WE CARE | ||

| Access to health care | ○ | • | |||||

| Child care | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Clothing | ○ | ||||||

| Education | ○ | ○ | • | • | ○ | ||

| Employment | ○ | ⦿ | ⦿ | ○ | |||

| Finances | Income/poverty | • | |||||

| Financial stress | • | • | |||||

| Food | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Housing | Housing instability/insecurity | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Housing quality | ○ | ⦿ | |||||

| Immigration/migration | • | ○ | |||||

| Incarceration | ○ | ||||||

| Primary language | ○ | • | ○ | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | • | • | |||||

| Residential address | • | • | |||||

| Safety | General safety (including nonspecific abuse) | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Child abuse | ○ | ||||||

| Intimate partner violence | • | • | ○ | ||||

| Neighborhood safety | |||||||

| Social connections/isolation | ○ | • | ○ | ||||

| Stress | • | • | ○ | ○ | |||

| Transportation | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||

| Utilities | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Veteran status | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Total percentage of domains included in screener that are represented fully or partially in existing codes | 25% (3/12) | 27% (3/11) | 100% (7/7) | 38% (8/21) | 0% (0/5) | 0% (0/7) | |

• indicates LOINC and/or SNOMED CT codes existed for all questions/answers in this domain on the screening tool.

⦿ indicates that LOINC and/or SNOMED CT codes existed for some questions/answer choices on the screening tool in this domain.

○ indicates no questions/answers in this domain on the screening tool had corresponding LOINC and/or SNOMED CT codes.

Gray boxes indicate that domain is not part of the screening tool.

Across LOINC and SNOMED CT, there were 118 unique coded questions/question panels related to SDH domains. In 15 cases, questions or panels were coded in both LOINC and SNOMED CT. In all other cases, LOINC and SNOMED CT coded different questions related to the same social domains. For example, within the “Stress” domain, only LOINC has a code for the Occupational Stress Questionnaire, only SNOMED CT has a code for the Life Events Inventory, and both LOINC and SNOMED CT have codes for the Perceived Stress Scale. Two SDH domains had no encoded screening questions (“Clothing” and “Incarceration”).

In addition to codes relating to domain-specific questions 50% (n = 10) of the domains had a SNOMED CT procedure code to account for whether screening had been conducted for that domain. Two additional CPT codes represented nondomain specific social screening procedures.

Assessment/diagnosis codes

Nearly all social domains (90%, n = 18) had Assessment/Diagnosis codes, with a median of 20 Assessment/Diagnosis codes per SDH domain, including SNOMED CT and ICD-10-CM child and parent codes. Two domains lacked Assessment/Diagnosis codes: “Childcare” and “Residential Address.” Most of the existing Assessment/Diagnosis codes were SNOMED CT child codes (426 out of 686). There were fewer SNOMED CT parent codes since parent codes were rarely domain-specific and/or did not reflect assessments. Six domains lacked any domain-specific ICD-10-CM codes (“Childcare,” “Clothing,” “Primary Language,” “Residential Address,” “Transportation,” and “Utilities”). We found 37 general social ICD-10-CM codes. As described earlier, these codes were related generally to social needs, but not to a specific SDH domain.

Treatment/intervention codes

In the Treatment/Intervention search, most domains (75%, n = 15) had at least one SNOMED CT code for each subcategory: Referral, Counseling/Education, and Provision of Service. On average, SDH domains had more Treatment codes for Provision of Service/Orders (mean 5.7 codes/SDH domain) than for the other Treatment subcategories (mean 3.7 Counseling/Education codes/SDH domain, and 2.5 Referral codes/SDH domain). As shown in Table 2, five SDH domains (25%) had no Referral code; three domains (15%) had no Counseling/Education code; and four domains (20%) had no Provision of Service code. Three SDH domains had no Treatment/Intervention codes in any subcategory (“Immigration/Migration,” “Residential Address,” and “Veteran Status”).

DISCUSSION

Health care systems in the US are increasingly encouraged to implement social screening tools and to intervene to reduce patients’ social risks in clinical settings.9–12 In this exploratory analysis, we aimed to better understand how existing health IT vocabularies could help document this rapidly expanding set of clinical activities. The search of four major medical vocabularies (LOINC, SNOMED CT, ICD-10-CM, and CPT) yielded 1095 codes related to 20 SDH domains found in common social screening tools in use across the US. Since this was not a comprehensive content coverage analysis, the number of codes we found is likely to be a conservative estimate.

Usefulness of current codes to meet practice needs

An important question surfaced by our results is how to interpret recent studies that suggest clinical activities around patients’ socioeconomic circumstances are rarely captured in electronic documentation.21–23 Though the total number of codes was much higher than we hypothesized we would find, our analysis suggests that existing SDH codes do not consistently match practice needs. For example, in our screening analysis, coded questions in LOINC and SNOMED CT failed to routinely correspond to the specific questions/answers in the social screening tools. In other cases where the screening tool questions matched available codes, coded answers varied. For instance, the Hunger Vital Sign™ in SEEK includes yes/no responses whereas in AHC it includes often/sometimes/never responses, but coded answers only corresponded to the AHC version of the question. In another example, though 14 different Assessment codes exist for “Utilities,” they typically indicate lack of utilities (eg SNOMED CT codes 423798004 “Lack of cooling in house;” 105535008 “Lack of heat in house;” 105536009 “Living in housing without electricity”) rather than referring to inability to pay for utilities. Yet clinical screening tools and interventions often focus on affordability (eg inability to pay bills), which was not included in codes related in this domain. There were also specific instances where there were no relevant codes for particular SDH domains or corresponding clinical activities. For example, there were no Screening codes for “Clothing” or “Incarceration”; no Assessment/Diagnosis codes for “Child care”; and no Treatment/Intervention codes for “Immigration/Migration” or “Veteran Status”. Ten of 20 domains lacked screening procedure codes (ie indicating whether screening was conducted at all). Overall, there were many more SDH Assessment/Diagnosis codes than codes for documenting screening procedures, screening results, or interventions, which limits the capacity to record these clinical activities.

Although our results suggest that existing SDH codes are insufficient to document existing SDH clinical activities, a comprehensive analysis of the quality of match between existing codes and clinical activities was outside the scope of this exploratory work. To conduct this critical next step, clinical content experts (patients and providers), policy makers, and informaticists will need to achieve consensus on what is “useful” for SDH codes to document—which screening panels, what level of granularity, which interventions, and for what purposes. We suggest this would be best accomplished by a domain-by-domain, multistakeholder process to further evaluate the utility of existing codes to meet clinical practice needs. Future efforts both to harmonize and organize codes by domain (eg by using value sets) and across clinical workflows could make social codes both more easily accessible and more easily aggregated across systems.56 As reimbursement policies related to social screening and interventions in clinical settings develop, this interoperability also will help ensure that any required documentation is matched by available standards.

Limitations

The goal of this work was to explore the existing capacity for SDH coding in four medical vocabulary systems. Beyond the limitations inherent in an exploratory approach, the study was constrained by search engine rules. We were also limited by the set of social domain search terms. Although we included key terms relevant to each domain that were recommended by consulting experts, it is possible we missed important terms. A strength of our design was that we crosschecked findings with additional references and obtained feedback on the design and search output from a broad group of national experts, including leaders from the four standards development organizations.

Next steps

By conducting a clinically framed analysis to describe the capacity of medical vocabularies to reflect SDH-related activities, our findings help to translate a largely hypothetical national conversation about whether SDH clinical activities should be coded to a more pragmatic conversation on how existing SDH codes are organized and where to supplement, modify, or replace codes to align with clinical workflows. Future work driven by experts in specific domains and in partnership with informaticists and standards development organizations could focus on a more mature set of SDH domains (eg food insecurity) in order to develop more streamlined processes for code generation, maintenance, and utilization. Given the rapid expansion of SDH-related activities in the US health care system, there is a short window where such a process could make a substantive contribution to standardization.

CONCLUSION

Health care sector activities around SDH have reached a level that demands more standardized collection of SDH and social needs-specific data in EHRs. This can facilitate patient care, population health management, community health improvement, value-based payment, and research. This exploratory analysis of the current capacity of medical coding vocabularies to capture common SDH domains and related clinical activities reveals a wide range of available SDH codes. It also highlights important coding gaps. Additional effort is required to ensure that the existing codes align with practice-based activities. As coding gaps are filled, code value sets could help maximize interoperability by grouping like codes across different vocabularies. A more comprehensive, coherent, user-friendly SDH code set could in turn facilitate a rapidly evolving set of health care use cases.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

CONTRIBUTORS

AA, SD, CF, and LG all contributed to the work presented, including the generation of content for and revision and refinement of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the many expert advisors who provided thoughtful feedback on the code search and content of this article: Katie Allen, Vivian Auld, Michael Cantor, Terry Cullen, Lesley MacNeil, Michelle Proser, Albert Taylor, Daniel Vreeman, and Don Sweete.

FUNDING

Authors Arons, Fichtenberg, and Gottlieb’s work on this project was supported by Kaiser Permanente Grant CRN-5374-7544-15320.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. McGinnis JM, Foege WH.. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA 1993; 27018: 2207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR.. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002; 212: 78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGovern L, Miller G, Hughes-Cromwick P. Health policy brief: the relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Policy Brief. Health Aff. August 21, 2014. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20140821.404487/full/. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 4. Adler NE, Marmot M, McEwen BS, et al. Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations: Social, Psychological, and Biological Pathways. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Booske BC, Athens JK, Kindig DA, et al. County Health Rankings Working Paper: Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Orszag PR, Ellis P.. The challenge of rising health care costs-a view from the Congressional Budget Office. N Engl J Med 2007; 35718: 1793.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA 2000; 2844: 483–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM.. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9. AAP Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics 2016; 137 (4): e20160339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Social Determinants of Health Policy. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/social-determinants.html. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- 11. About the National Quality Strategy. https://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/about/index.html. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 12. Wyatt R, Laderman M, Botwinick L, et al. Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, et al. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009; 30117: 1771–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA 2009; 30113: 1349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shubert V, Bernstine N.. Moving from fact to policy: housing is HIV prevention and health care. AIDS Behav 2007; 11 (6 Suppl): 172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE.. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med 2017; 535: 719–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, et al. Integrating social and medical data to improve population health: opportunities and barriers. Health Aff 2016; 3511: 2116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Quality Forum. Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status or Other Sociodemographic Factors. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. King RJ, Garrett N, Kriseman J, et al. A community health record: improving health through multisector collaboration, information sharing, and technology. Prev Chronic Dis 2016; 13 (9): 160101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Navathe AS, Zhong F, Lei VJ, et al. Hospital readmission and social risk factors identified from physician notes. Health Serv Res 2018; 532: 1110–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Torres JM, Lawlor J, Colvin JD, et al. ICD social codes: an underutilized resource for tracking social needs. Med Care 2017; 559: 810–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cantor MN, Thorpe L.. Integrating data on social determinants of health into electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018; 374: 585–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hripcsak G, Forrest CB, Brennan PF, et al. Informatics to support the IOM social and behavioral domains and measures. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015; 224: 921–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 2015. Edition Certification Companion Guide: Social, Psychological, and Behavioral Data - 45 CFR 170.315(a)(15) 2017.

- 26. DeSilvey S, Ashbrook A, Sheward R, et al. An Overview of Food Insecurity Coding in Health Care Settings: Existing and Emerging Opportunities. Boston, MA: Children's Health Watch; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27. DiPietro B, Edgington S.. Ask and Code: Documenting Homelessness Throughout the Health Care System. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winden TJ, Chen ES, Melton GB.. Representing residence, living situation, and living conditions: an evaluation of terminologies, standards, guidelines, and measures/surveys. Proc Am Med Inform Assoc 2016; 2016: 2072. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajamani S, Chen ES, Lindemann E, et al. Representation of occupational information across resources and validation of the occupational data for health model. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 252: 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aldekhyyel R, Chen ES, Rajamani S, et al. Content and quality of free-text occupation documentation in the electronic health record. Proc Am Med Inform Assoc 2016; 2016: 1708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buck C. News Alert: ICD-11 Codes Released by WHO. St. Paul, MN: ICD10 Monitor; 2018: https://www.icd10monitor.com/news-alert-icd-11-codes-released-by-who. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 32. Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. Terminology Standards 2018. https://www.himss.org/library/interoperability-standards/terminology-standards. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 33. Hicks A, Hanna J, Welch D, et al. The ontology of medically related social entities: recent developments. J Biomed Semantics 2016; 7: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Association of Community Health Centers. PRAPARE: Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences. Washington, DC: National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc., Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, and Oregon Primary Care Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Billioux A, Verlander K, Anthony S, et al. Standardized Screening for Health-Related Social Needs in Clinical Settings. The Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36. HealthLeads. Social Needs Screening Toolkit. Boston, MA: HealthLeads; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. University of Maryland School of Medicine. SEEK Parent Questionnaire – R 2017. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/77e10d_c5ec3492b03d4540b20874d622ef3557.pdf. Accessed December 2017.

- 38. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015; 135: e304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA 1993; 26918: 2386–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fiscella K, Tancredi D, Franks P.. Adding socioeconomic status to Framingham scoring to reduce disparities in coronary risk assessment. Am Heart J 2009; 1576: 988–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Post P. Mobile Health Care for Homeless People: Using Vehicles to Extend Care. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM.. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med 2012; 36711: 1025–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weiner S. I can't afford that! J Gen Intern Med 2001; 166: 412–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Saha S, Fernandez A, Perez-Stable E.. Reducing language barriers and racial/ethnic disparities in health care: an investment in our future. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22 (S2): 371–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Basu A, Kee R, Buchanan D, et al. Comparative cost analysis of housing and case management program for chronically ill homeless adults compared to usual care. Health Serv Res 2012; 47 (1 Pt 2): 523–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sandel M, Hansen M, Kahn R, et al. Medical-legal partnerships: transforming primary care by addressing the legal needs of vulnerable populations. Health Aff 2010; 299: 1697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weintraub D, Rodgers MA, Botcheva L, et al. Pilot study of medical-legal partnership to address social and legal needs of patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010; 21 (2 Suppl): 157–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fraze T, Lewis VA, Rodriguez HP, et al. Housing, transportation, and food: how ACOs seek to improve population health by addressing nonmedical needs of patients. Health Aff 2016; 3511: 2109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Searchable LOINC database. https://search.loinc.org/searchLOINC/. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 50.SNOMED CT Brower (US edition). http://browser.ihtsdotools.org/. Accessed March 2018.

- 51.ICD-10-CM Tabular List of Diseases and Injuries. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 52. Integrated health model initiative: terminology search tool. https://ihmi.clinicalarchitecture.com/browser/#/search/results. Accessed Mar 15, 2018.

- 53. American Academy of Pediatrics. Coding for Pediatric Preventive Care. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 54.I-MAGIC. https://imagic.nlm.nih.gov/imagic/code/map. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 55. Compendium of Medical Terminology Codes for Social Risk Factors. http://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/mmi/compendium-medical-terminology-codes-social-risk-factors. Accessed October 4, 2018

- 56. VSAC Frequently Asked Questions. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/vsac/support/faq/faq.html. Accessed October 4, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.