Abstract

Importance:

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy of reproductive-aged women. Women with PCOS are at increased risk for developing several metabolic and reproductive abnormalities, including metabolic syndrome. Underlying the combined metabolic and reproductive dysfunction is lipotoxicity, defined as the ectopic deposition of lipid in non-adipose tissue where it induces oxidative stress linked with insulin resistance and inflammation.

Objective:

To examine what metabolic components underlie insulin resistance in PCOS, how lipotoxicity through insulin resistance impairs metabolism and reproduction in these women, and why evidence-based, individualized management is essential for their care.

Evidence Acquisition:

PubMed search was performed using relevant terms to identify journal articles related to the subject. Relevant textbook chapters were also used.

Results:

PCOS by Rotterdam criteria represents a complex syndrome of heterogeneous expression with variable adverse metabolic and reproductive implications. Women with classic PCOS are often insulin-resistant and at greatest risk of developing metabolic syndrome with preferential fat accumulation and weight gain. Moreover, PCOS women may also have an altered capacity to properly store fat, causing ectopic lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue, including the ovaries, where it can perpetuate insulin resistance and inflammation and harm the oocyte.

Conclusions and Relevance:

A personalized approach to managing PCOS is essential to improve the health of all PCOS women through cost-effective prevention and/or treatment, to minimize the risk of pregnancy complications in those individuals wishing to conceive, and to optimize the long-term health of PCOS women and their offspring.

Target Audience: Obstetricians and gynecologists, family physicians

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex, heterogeneous syndrome of reproductive-aged women characterized by clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, oligo-anovulation and polycystic ovarian morphology. To diagnose PCOS, other causes of hyperandrogenism and endocrinopathies must be excluded, including congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, androgen-producing tumors and exogenous androgen administration (1).

Three different diagnostic criteria currently exist to diagnose PCOS, including 1990 National Institutes of Health (NIH), Androgen Excess and PCOS (AE-PCOS) Society, and Rotterdam (1, 2, 3, 4) criteria. The 1990 NIH sponsored conference defines PCOS as clinical hyperandrogenism and/or hyperandrogenemia with oligo-anovulation, excluding other endocrinopathies. The AE- PCOS Society criteria for diagnosing PCOS are a modification of the 1990 NIH criteria by considering hyperandrogenism as the cardinal PCOS feature and defining PCOS as hyperandrogenism (clinical and/or biochemical) and ovarian dysfunction (oligo-anovulation and/or polycystic ovaries), excluding other endocrinopathies. The Rotterdam PCOS criteria includes at least two of the following three features: 1) clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, 2) oligo-anovulation, and 3) polycystic ovaries, excluding other endocrinopathies. The Rotterdam diagnostic criteria are currently recommended for clinical use (5), but nearly double the 6–10% prevalence of PCOS based on earlier 1990 NIH criteria (6).

Properly diagnosing PCOS requires accurately defining its key clinical features. Androgen excess is defined by either hirsutism, as quantified by the modified Ferriman-Gallwey Scale with different cutoffs based on ethnicity (7, 8), or elevated biochemical hyperandrogenism measured by appropriate assays (9). Oligo-anovulation refers to menstrual cycles less than or greater than 21 or 35 days, respectively, or less than 8 times annually (3). The third criteria, polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM), was until recently defined by 12 or more follicles per ovary or an ovarian volume > 10 cm3 in the absence of corpora lutea or cysts (2). With improved sonographic imaging, however, a recent task force has recommended increasing the threshold for follicle count in adult women to more than 20 follicles using an endo-vaginal ultrasound transducer with a frequency band width including 8 MHz (5).

The Rotterdam PCOS definition creates different phenotypes, including classic PCOS (hyperandrogenism with oligo-anovulation with or without PCOM [same as the 1990 NIH criteria]), ovulatory PCOS (hyperandrogenism and PCOM), and non-androgenic PCOS (oligo-anovulation and PCOM) (10). While not part of the PCOS diagnosis, metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), hyperlipidemia, excess adiposity and metabolic syndrome often coexist with PCOS depending upon its phenotypic expression. Classic PCOS patients have higher metabolic risk than ovulatory PCOS patients who comparatively have a lower body mass index (BMI) and a lesser degree of hyperinsulinemia. Non-androgenic PCOS patients have the lowest metabolic risk (11, 10).

To understand the mechanism behind the compromised reproductive outcomes associated with metabolic disease in PCOS, it is essential to understand the adverse effects of increased adiposity, abnormal fat distribution and ectopic lipid deposition (i.e., lipotoxicity) on metabolic and reproductive health. This review examines each of these metabolic abnormalities common to PCOS and how they impact reproductive outcomes. It provides an evidence-based approach to metabolic evaluation and preconception management before pregnancy, with an emphasis on assisted reproduction.

OBESITY AND BODY FAT DISTRIBUTION

Obesity is a disease of excess body fat that is closely linked to insulin resistance and an increased risk of developing metabolic diseases, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, and cardiovascular disease (12). With the prevalence of obesity in all women increasing, 50–60% of PCOS women are overweight or obese. Although not intrinsic to PCOS itself, obesity exacerbates metabolic dysfunction in PCOS women, worsening their phenotype (13, 14). Importantly, obesity alone can mimic the appearance of PCOS, by suppressing sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), which in turn increases serum free testosterone (T) levels and promotes menstrual irregularity (15).

In addition, women with classic PCOS preferentially accumulate abdominal fat, known as android obesity, as a crucial component of metabolic syndrome (16, 17). Metabolic syndrome consists of several metabolic factors that increase the risk of developing T2DM and cardiovascular disease (18). Metabolic syndrome has been defined in various ways, all of which include abdominal obesity (defined by increased waist circumference), elevated blood pressure, hypertriglyceridemia, elevated fasting blood glucose, and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels (19, 20). The two most commonly used definitions of metabolic syndrome are from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the National Cholesterol Education Program-Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III). Differences between these diagnostic criteria are that the IDF criteria considers ethnic differences in waist circumference cutoffs and has a lower threshold for defining hyperglycemia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definition of Metabolic Syndrome in Women by National Cholesterol Education Program-Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) and International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria

| NCEP-APT III (≥3 of the following criteria) | IDF (Central obesity + ≥2 of the following criteria) | |

|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference (WC) | >88 cm | WC defined by ethnicity: ≥80 cm for: Europids, South Asian, Chinese, Ethinic South/Central American, Sub-Saharan African, Middle East ≥90 cm for: Japanese or BMI ≥30 kg/m2 |

| Blood pressure (BP) | ≥130/85 mm Hg | Systolic BP ≥130 mm Hg or Diastolic BP ≥85 mm Hg or treatment for hypertension |

| Triglycerides (TG) | ≥150 mg/dL | ≥150 mg/dL or treatment for hypertriglyceridemia |

| Fasting blood glucose | ≥110 mg/dL | ≥100 mg/dL or prior T2DM |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) | <50 mg/dL | <50 mg/dL or treatment for low HDL |

Women with classic PCOS have a 2–3 fold higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome (33–47%) than that of age-matched normal women, which is reduced by lower abdominal fat accumulation (21). The incidence of metabolic syndrome, however, is related not only to obesity and body fat distribution, but also to ethnicity and PCOS phenotype. For example, South Asian women have a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome at a lower BMI and smaller waist circumference than age-matched women of different ethnicities (Caucasian, Hispanic, African American), with such differences likely related to ethnic variation in body fat distribution. Moreover, Caucasian women with classic PCOS have a 2-fold risk increased risk of metabolic syndrome compared with non-androgenic PCOS women (22, 23).

Increased abdominal (android) adiposity in women with classic PCOS is associated with insulin resistance, increased intra-abdominal fat deposition, and greater waist-to-hip ratio compared to BMI-matched normal women (24). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also have been used to assess total abdominal and intra-abdominal fat accumulation, respectively. Some (25), but not all (26, 27) such studies have shown preferential intra-abdominal fat accumulation in PCOS versus normal women, likely due to varying imaging protocols and PCOS diagnostic criteria. A recent study in normal-weight women found increased intra-abdominal fat content in classic PCOS women with underlying hyperinsulinemia compared with age- and BMI-matched normal women (25).

INSULIN RESISTANCE

Hyperinsulinemia from insulin resistance is common in PCOS women and is associated with impaired insulin receptor signaling and decreased insulin-mediated glucose uptake (28). Consequently, impaired glucose tolerance and T2DM occur in 30–40% and 10% of PCOS women by the fourth decade, respectively (21), with classic PCOS women having a 2.5-fold increased prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance versus normal women (13) that is accompanied by dyslipidemia, hyperandrogenemia and anovulation. The resulting hyperinsulinemia acts synergistically with luteinizing hormone (LH) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 to promote ovarian androgen production and also to decrease hepatic SHBG and IGF-binding protein production, which in turn increases circulating free T levels (29). Consequently, improvement in insulin sensitivity with insulin-sensitizing medications in some PCOS women can reduce androgen levels and restore ovulation. Additionally, improved insulin sensitivity is associated with decreases in both waist circumference and intra-abdominal fat by computerize tomography (CT) (30).

Importantly, classic PCOS women (by NIH criteria) are at the greatest risk of developing T2DM and metabolic syndrome, although a normal BMI significantly ameliorates these metabolic risks even in these PCOS women (21). Ovulatory PCOS women (included in Rotterdam and AE-PCOS criteria) have a lower BMI and lesser degrees of hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenism than NIH-defined PCOS women. Women with non-androgenic PCOS appear least affected regarding metabolic risk (4, 21, 31).

ADIPOSE TISSUE AND LIPOTOXICITY

Both obesity (too much adiposity) and lipodystrophy (too little adiposity) can cause metabolic derangements, including increased risk of developing T2DM, liver disease and heart disease (32). With lipodystrophy, the fat mass lacks the ability to store excess lipids in subcutaneous (SC) adipose tissue. With obesity, on the other hand, the capacity of SC adipose to safely store fat has been reached or exceeded. In both cases, excess lipids accumulate in ectopic, non-adipose, sites, such as liver, skeletal muscle and heart, which causes similar metabolic defects (32, 33).

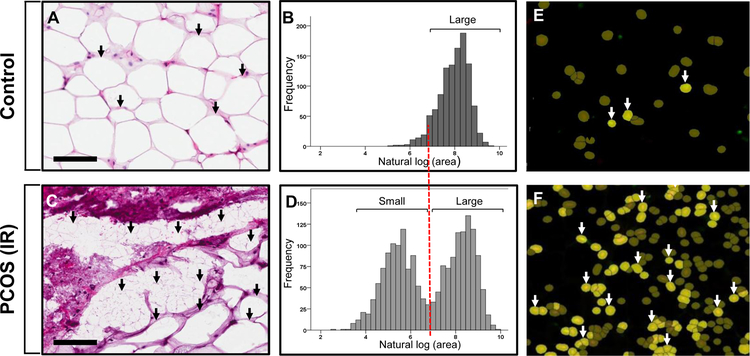

Subcutaneous adipose is the safest location to store fat for later free fatty acid (FFA) release. It normally increases its fat storage capacity during excess FFA influx by recruiting new adipose cells, called adipocytes, through hyperplasia to complement enlargement of adipocytes already present (hypertrophy) (32). If energy intake exceeds the capacity of SC adipose to safely store fat, however, local hypoxia causes invasion of inflammatory cells. Figure 1 shows the differences between SC abdominal adipose from a PCOS woman with metabolic syndrome unresponsive to medical managment vs. a normal ovulatory woman in adipocyte size, cell size distribution and adipose tissue macrophage (34) infiltration. Simultaneously, excess lipid is deposited elsewhere. This process, called lipotoxicity, refers to ectopic lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue where it induces oxidative/endoplasmic reticulum stress tightly linked with insulin resistance and inflammation.

FIGURE 1:

Differences between SC abdominal adipose of a PCOS woman with metabolic syndrome unresponsive to medical management vs. a normal ovulatory woman in adipocyte size, cell size distribution and adipose tissue macrophage (34) infiltration. Adipose of each woman was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A and C); images were digitally scanned and quantified by automated image analysis software after manual cell circling. Adipocyte size was transformed using square root transformation, with a log value < 7.0 μm2 (equivalent, 60 μm diameter) to identify a subpopulation of small adipocytes, (B and D); adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) identifed by immunofluorescence as CD68/DAPI(+) cells were quantified by the same imaging system (E-F). Note the bimodaI adipocyte distribution of small and large adipocytes in the PCOS vs. the normal woman, along with increased ATM infiltration indicating inflammation. Black arrows, small or large adipocytes; white arrows, ATMs. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Lipotoxicity emphasizes cell dysfunction from ectopic lipid accumulation rather than excess body fat storage per se (25, 35, 36). When excess cellular uptake of lipid occurs in non-adipose cells, cellular oxidative stress with formation of cytotoxic, highly-reactive lipid peroxides damages the intracellular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria (37, 38, 39). Subsequent accumulation of unfolded proteins and calcium release activate a compensatory reaction, known as the unfolded protein response (UPR), which promotes cell cycle arrest, reduces protein synthesis and activates ER-associated protein degradation (40, 41). If the UPR fails to restore homeostasis, excess cellular FFA influx induces ER dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, and finally cellular apoptosis (37, 40, 41).

Adipose also can release FFA through a process called lipolysis. Impaired insulin suppression of lipolysis increases circulating FFA levels which can diminish glucose uptake in peripheral tissues and also can impair insulin inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis, thereby elevating circulating glucose levels (42).

Androgen affects both SC adipose function and abdominal fat distribution. Hyperandrogenism in normal-weight PCOS women by NIH criteria is associated with preferential intra-abdominal fat deposition and increased numbers of small SC abdominal adipocytes, perhaps representing constrained SC adipose storage that could promote lipotoxicity (25). Moreover, in overweight PCOS women, SC abdominal adipose has enlarged adipocytes, along with decreased insulin-mediated glucose utilization, reduced glucose transporter type 4 expression, and lipolytic catecholamine resistance from diminished protein levels of β2-adrenergic receptor, hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), and protein kinase A regulatory-IIβ component (PKA-RegIIβ) (43, 44, 45, 46). These findings suggest an altered capacity of SC abdominal adipose to safely store fat, which could further enhance FFA uptake in non-adipose cells and intra-abdominal fat.

Adipose also secretes several hormones called adipokines, with leptin being the first adipokine identified to regulate food intake and energy expenditure. In general, leptin acts within the central nervous system to reduce hunger with sufficient energy intake; its circulating levels represent the amount of adipose present in the individual. Circulating leptin levels in PCOS women, controlling for BMI, generally do not differ from healthy controls (47), and positively correlate with insulin resistance and obesity (47, 48), perhaps due to altered ligand-receptor interactions. Adiponectin is another adipokine that, in contrast to leptin, has insulin-sensitizing, anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory actions (49). Controlling for BMI, circulating adiponectin levels are lower in PCOS than normal women and are associated with insulin resistance (49). Several other adipokines also exist and are currently under investigation.

LIPOTOXICITY AND OVARIAN FUNCTION

Oocyte competence is defined as the ability of an oocyte to complete meiosis, fertilize, and undergo embryonic and term development (50). Bidirectional signaling via gap junctions in the cumulus cell-oocyte complex regulates this process. The relationship between PCOS and oocyte development is not fully understood for many reasons. First, there are ethical limitations regarding research on human oocytes and embryos. Additionally, each follicle has its own microenvironment that impacts its own oocyte. Therefore, if the follicle, follicular fluid, oocyte, and embryo are not carefully tracked as a unit, outcomes regarding the impact of a particular microenvironment on the egg, embryo, and offspring are difficult to monitor, particularly if multiple embryos are transferred in a given in vitro fertilization (IVF)/embryo transfer (ET) cycle. Additionally, oocytes gradually acquire essential molecular components for development over time (51, 52, 53), making translational studies difficult. Therefore, our knowledge of the relationship between PCOS and human oocyte competence, is based on indirect markers of oocyte development, including gene expression, follicular fluid hormone levels in vivo (when able to be tracked) and in vitro, as well as animal studies (54, 55, 56, 57).

In female mice fed a high-fat diet, lipid accumulates in oocytes both before and after ovulation, while cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) show increased ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, along with excess DNA fragmentation and apoptosis in both cumulus and granulosa cells (58). In these same overfed mice, reduced ovulation rates accompany impaired oocyte fertilization (58), suggesting ovarian cell lipotoxicity. In support of this, increased adiposity in women elevates insulin, triglyceride (TG) and C-reactive protein levels, increases ER stress gene expression in granulosa cells and lowers IVF-related pregnancy rates, while increased reactive oxygen species and decreased total antioxidant capacity also can lead to IVF pregnancy failure (24, 58, 59, 60, 61).

CLINICAL EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Metabolic Evaluation of PCOS

An appropriate metabolic evaluation in PCOS women is essential from both reproductive and general health standpoints. Guidelines have been established to direct appropriate metabolic evaluation in PCOS women (62, 63), with specific clinical features of disease, including obesity, ethnicity and PCOS phenotype, dictating screening strategies.

Baseline glucose-insulin homeostasis should be assessed in all women with classic PCOS (by NIH criteria) due to their increased risk of developing T2DM. This can be done with a 2-hour oral 75-gram glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or serum HgbA1C level, although the former is the clinical gold standard. A number of surrogate indices for insulin resistance have been used, including glucose/insulin ratio, homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) and quantitative sensitivity check index (QUICKI) based on fasting insulin and glucose levels. However, these indices have been found to have limited sensitivity with true insulin resistance and are not recommended for clinical use (64). Additionally, when assessing an OGTT, there is limited value in checking insulin levels in most cases as little data exist regarding whether elevated insulin levels alone predict need for treatment (65, 66). An OGTT is recommended in high-risk women including those with classic PCOS, acanthosis nigricans, obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2 or >25 kg/m2 in Asian populations), advanced maternal age (> 40 years), family history of T2DM or gestational diabetes mellitus and individuals wishing to conceive. Glycemic status should be assessed at the initial evaluation and every one to three years thereafter (5, 63).

The increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in PCOS women as a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) requires assessment of all of its components, as delineated in Table 1. In addition to assessing glucose-insulin homeostasis, these include measurements of blood pressure, BMI and waist circumference, as well as fasting serum lipid levels (i.e., HDL, low-density lipoprotein [LDL, non-HDL and TG levels). An increased waist circumference at the iliac crest and an elevated fasting serum non-HDL level are helpful in assessing increased CVD risk, particularly in women with classic PCOS (63). In addition, skin should be examined for acanthosis nigricans, and nutrition, physical activity, psychosocial stress, sleep apnea and smoking status also should be assessed.

Preconception Assessment and Management

Women with PCOS have higher rates of infertility, typically thought to represent anovulation. However, metabolic dysfunction in these women likely also plays a large role in infertility. Although not all PCOS women are obese, periconception obesity in either parent affects fertility (67), possibly through the adverse effect of lipotoxicity on the gonads and their gametes.

Being overweight or obese, regardless of PCOS, increases the risk of pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preterm birth, macrosomia, and rates of cesarean delivery (68). Therefore, preconception is the ideal time to educate, counsel, and help implement lifestyle changes in women desiring pregnancy. If PCOS women are overweight or obese, improved diet and increased exercise should be recommended before conception (23) because reducing weight by 5–10% can reinstate ovulation and fertility (69, 70, 71). Although the best diet for PCOS women remains unclear, some studies along with clinical experience suggest that diets low in simple carbohydrates may be preferred (72). In terms of exercise, the American Heart Association recommends for adults 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise or 75 minutes per week of vigorous cardiovascular activity, or a combination of the two for overall cardiovascular health (www.heart.org). Longer periods of vigorous exercise can be employed to improve blood pressure (www.heart.org). Weight loss in obese women with PCOS significantly improves metabolic status (73).

Metformin is often used in treating PCOS (5) and can directly impact ovarian steroidogenesis independent of its impact on insulin sensitivity (74). Metformin use in pregnancy can decrease the risk of gestational diabetes and preterm delivery in women with and without PCOS (75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80). There is concern, however, regarding the risk to offspring exposed in utero to metformin. Some studies suggest no harm and possible reduced pregnancy complications (79, 80, 81, 82), while another shows an increased risk of increased adiposity in 4-year-old offspring of PCOS women receiving metformin during pregnancy versus offspring of PCOS women receiving placebo (83). Furthermore, one study showed that metformin treatment of overweight/obese PCOS mothers was associated with larger fetal and neonatal head size, while similar metformin treatment of normal-weight PCOS mothers was accompanied by fetal growth restriction (84).

In women who remain morbidly obese, or obese with comorbid conditions despite lifestyle modifications or medical management, a surgical approach to weight loss may be considered (85). Bariatric surgery can restore ovulation, reduce serum androgens and improve sexual function. It can also reduce maternal risks of gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, hypertensive disorders and macrosomia. However, restrictive with malabsorptive surgical procedures can cause nutritional deficiencies of protein, iron, vitamins A, B12 and D, folate, and calcium potentially linked with adverse neonatal outcomes (86). Adverse outcomes for pregnancy after bariatric surgery have also been noted, including higher risk of small for gestational age infants and shorter duration of pregnancy, with a trend towards a higher risk of neonatal mortality (87). Therefore, pregnancy is not recommended for at least one year after bariatric surgery due to potential nutritional deficiencies from rapid maternal weight loss. Patient age, delay in conception, preconception nutrition and micronutrient supplementation also must be considered in the decision to recommend bariatric surgery.

Metabolic management before IVF

Many studies have now linked high BMI with negative IVF outcomes, including the need for higher doses of gonadotropins, fewer oocytes retrieved, higher cycle cancellation rates, reduced pregnancy and live birth rates and higher miscarriage rates (88, 89, 90). Women with normal BMI have higher IVF-related live-birth rates across all age groups compared to overweight and obese women (91). However, patient age needs to be considered when recommending weight loss before IVF. In general, in women less than 35 years, weight loss before IVF can be considered, since pregnancy rates are higher with a lower BMI even at an older age (91). However, once a woman reaches the age of 35 years, the time needed to lose weight will likely negate the improved pregnancy rate with a lower BMI (91).

A critical question is whether preconception weight loss actually improves pregnancy outcomes by IVF, eventually resulting in healthier mothers and babies. One study showed that for each unit reduction in BMI, the odds of achieving a pregnancy following IVF could improve by 19% (92). Another study showed that weight loss of at least 1 kg in overweight or obese infertility patients increased the yield of mature oocytes, but did not correlate with clinical pregnancy or live birth rates (93). A study randomizing women to severe calorie restriction followed by IVF versus IVF alone found that weight loss correlated with spontaneous pregnancies in the intervention group, but there was no difference in IVF outcomes (94). Another study randomizing overweight/obese women to 5–9 weeks of diet and exercise versus standard treatment found that the diet/exercise group lost more weight, but that pregnancy and live birth rates did not differ; nevertheless, a reduction in waist circumference, regardless of treatment, was associated with increased odds of pregnancy (73).

Conversely, another study showed that women with weight loss of at least 10% of maximum body weight resulted in significantly higher conception and live birth rates when spontaneous conceptions and IVF-related conceptions were combined compared to women without weight loss; a trend towards higher IVF-related pregnancy rates accompanied weight loss (95). Furthermore, a study randomizing obese women to 12 weeks of weight loss by low calorie diet and exercise versus weight loss counseling alone found greater weight loss, higher pregnancy (48% vs 14%) and live birth (44% vs 14%) rates, and fewer treatment cycles to pregnancy (2 vs 4) in the intervention group (96).

Looking more closely at dietary factors, in one study that randomized overweight/obese women to 12 weeks of diet and exercise versus standard treatment, women with higher consumption of omega 6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and linoleic acid were more likely to conceive (97). Another study similarly randomizing obese women to 12 weeks of diet and exercise versus standard treatment found no change in per cycle pregnancy rates, but showed significantly higher cumulative live-birth rates (61.9% vs 30%) (98). Of concern, recommendation for severe caloric restriction before conception is associated with high drop-out rates and other adverse health effects and may actually be harmful for pregnancy (99). A large study randomizing nearly 600 obese infertile women to either a 6-month weight loss intervention followed by 18 months of infertility treatment or prompt infertility treatment for 24 months demonstrated a lower live birth rate in the weight loss group than the prompt fertility treatment group (100). Therefore, preconception weight loss may allow for more spontaneous pregnancies, but may not consistently improve pregnancy outcomes by IVF (95).

CONCLUSION

As the most common hormone disorder of young women, PCOS is a syndrome of heterogeneous expression with variable adverse reproductive and metabolic implications. Knowing how its reproductive and metabolic dysfunction vary by PCOS phenotype is the key to developing an individualized healthcare approach for each PCOS woman. To do so, this approach also must consider the collective adverse effects of obesity on insulin sensitivity, increased abdominal fat as a component of metabolic syndrome, and lipotoxicity on cellular dysfunction from ectopic lipid accumulation. Such a personalized approach to the diagnosis and treatment of PCOS promises to improve the health of all PCOS women through cost-effective prevention and/or treatment, to minimize the risk of pregnancy complications in those individuals wishing to conceive and to optimize the long-term health of PCOS women and their offspring.

Funding:

This study was funded in part by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award P50HD071836 through the Oregon National Primate Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zawadzki JK DA. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: Toward a rational approach. Boston, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotterdam EA-SPCWG. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril 2009;91:456–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang RJ DD. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Hyperandrogenic States. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1602–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod 2010;25:544–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin KA, Chang RJ, Ehrmann DA, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1105–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao X, Ni R, Li L, et al. Defining hirsutism in Chinese women: a cross-sectional study. Fertil Steril 2011;96:792–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legro RS, Schlaff WD, Diamond MP, et al. Total testosterone assays in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: precision and correlation with hirsutism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:5305–5313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4237–4245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welt CK, Gudmundsson JA, Arason G, et al. Characterizing discrete subsets of polycystic ovary syndrome as defined by the Rotterdam criteria: the impact of weight on phenotype and metabolic features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4842–4848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: executive summary. Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:899–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:347–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim SS, Norman RJ, Davies MJ, et al. The effect of obesity on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2013;14:95–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legro RS, Dodson WC, Gnatuk CL, et al. Effects of gastric bypass surgery on female reproductive function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:4540–4548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquali R, Casimirri F, Labate AM, et al. Body weight, fat distribution and the menopausal status in women. The VMH Collaborative Group. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1994;18:614–621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goverde AJ, van Koert AJ, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Indicators for metabolic disturbances in anovulatory women with polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosed according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria. Hum Reprod 2009;24:710–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassi E, Pervanidou P, Kaltsas G, et al. Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med 2011;9:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement: Executive Summary. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2005;4:198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med 2006;23:469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrmann DA, Liljenquist DR, Kasza K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of the metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijeyaratne CN, Seneviratne Rde A, Dahanayake S, et al. Phenotype and metabolic profile of South Asian women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): results of a large database from a specialist Endocrine Clinic. Hum Reprod 2011;26:202–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moran LJ, Norman RJ, Teede HJ. Metabolic risk in PCOS: phenotype and adiposity impact. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:136–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, et al. Scientific Statement on the Diagnostic Criteria, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Molecular Genetics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocr Rev 2015;36:487–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dumesic DA, Akopians AL, Madrigal VK, et al. Hyperandrogenism Accompanies Increased Intra-Abdominal Fat Storage in Normal Weight Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:4178–4188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchengast S, Huber J. Body composition characteristics and body fat distribution in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2001;16:1255–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber TM, Golding SJ, Alvey C, et al. Global adiposity rather than abnormal regional fat distribution characterizes women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:999–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunaif A Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. Endocr Rev 1997;18:774–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baillargeon JP, Nestler JE. Commentary: polycystic ovary syndrome: a syndrome of ovarian hypersensitivity to insulin? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:22–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasquali R, Gambineri A, Biscotti D, et al. Effect of long-term treatment with metformin added to hypocaloric diet on body composition, fat distribution, and androgen and insulin levels in abdominally obese women with and without the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:2767–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Panidis D. Unravelling the phenotypic map of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a prospective study of 634 women with PCOS. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:735–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammarstedt A, Gogg S, Hedjazifar S, et al. Impaired Adipogenesis and Dysfunctional Adipose Tissue in Human Hypertrophic Obesity. Physiol Rev 2018;98:1911–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pruis MG, van Ewijk PA, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, et al. Lipotoxicity and the role of maternal nutrition. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;210:296–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 2004;350:672–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorensen TI, Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Obesity as a clinical and public health problem: is there a need for a new definition based on lipotoxicity effects? Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1801:400–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the Metabolic Syndrome--an allostatic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1801:338–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z, Berk M, McIntyre TM, et al. The lysosomal-mitochondrial axis in free fatty acid-induced hepatic lipotoxicity. Hepatology 2008;47:1495–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ilieva EV, Ayala V, Jove M, et al. Oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress interplay in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2007;130:3111–3123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malhi H, Gores GJ. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 2008;28:360–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol 2004;14:20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev 1999;13:1211–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shulman GI. Ectopic fat in insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiometabolic disease. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2237–2238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunaif A, Segal KR, Shelley DR, et al. Evidence for distinctive and intrinsic defects in insulin action in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes 1992;41:1257–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manneras-Holm L, Leonhardt H, Kullberg J, et al. Adipose tissue has aberrant morphology and function in PCOS: enlarged adipocytes and low serum adiponectin, but not circulating sex steroids, are strongly associated with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:E304–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faulds G, Ryden M, Ek I, et al. Mechanisms behind lipolytic catecholamine resistance of subcutaneous fat cells in the polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2269–2273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenbaum D, Haber RS, Dunaif A. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: decreased expression of GLUT-4 glucose transporters in adipocytes. Am J Physiol 1993;264:E197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daghestani MH, Daghestani M, Daghistani M, et al. A study of ghrelin and leptin levels and their relationship to metabolic profiles in obese and lean Saudi women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Lipids Health Dis 2018;17:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Namavar Jahromi B, Dabaghmanesh MH, Parsanezhad ME, et al. Association of leptin and insulin resistance in PCOS: A case-controlled study. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd) 2017;15:423–428 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Farmakiotis D, et al. Adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2009;15:297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dumesic DA, Padmanabhan V, Abbott DH. Polycystic ovary syndrome and oocyte developmental competence. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2008;63:39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latham KE. Epigenetic modification and imprinting of the mammalian genome during development. Curr Top Dev Biol 1999;43:1–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moor RM, Dai Y, Lee C, et al. Oocyte maturation and embryonic failure. Hum Reprod Update 1998;4:223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albertini DF, Sanfins A, Combelles CM. Origins and manifestations of oocyte maturation competencies. Reprod Biomed Online 2003;6:410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood JR, Dumesic DA, Abbott DH, et al. Molecular abnormalities in oocytes from women with polycystic ovary syndrome revealed by microarray analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:705–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tesarik J, Mendoza C. Direct non-genomic effects of follicular steroids on maturing human oocytes: oestrogen versus androgen antagonism. Hum Reprod Update 1997;3:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dumesic DA, Schramm RD, Peterson E, et al. Impaired developmental competence of oocytes in adult prenatally androgenized female rhesus monkeys undergoing gonadotropin stimulation for in vitro fertilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:1111–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steckler T, Wang J, Bartol FF, et al. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone treatment causes intrauterine growth retardation, reduces ovarian reserve and increases ovarian follicular recruitment. Endocrinology 2005;146:3185–3193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu LL, Dunning KR, Yang X, et al. High-fat diet causes lipotoxicity responses in cumulus-oocyte complexes and decreased fertilization rates. Endocrinology 2010;151:5438–5445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jungheim ES, Macones GA, Odem RR, et al. Associations between free fatty acids, cumulus oocyte complex morphology and ovarian function during in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 2011;95:1970–1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seto-Young D, Avtanski D, Strizhevsky M, et al. Interactions among peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma, insulin signaling pathways, and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in human ovarian cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2232–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robker RL, Akison LK, Bennett BD, et al. Obese women exhibit differences in ovarian metabolites, hormones, and gene expression compared with moderate-weight women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1533–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;89:251–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril 2012;97:28–38 e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tosi F, Bonora E, Moghetti P. Insulin resistance in a large cohort of women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a comparison between euglycaemic-hyperinsulinaemic clamp and surrogate indexes. Hum Reprod 2017;32:2515–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barber TM, Wass JA, McCarthy MI, et al. Metabolic characteristics of women with polycystic ovaries and oligo-amenorrhoea but normal androgen levels: implications for the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Legro RS, Castracane VD, Kauffman RP. Detecting insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: purposes and pitfalls. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2004;59:141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lane M, Zander-Fox DL, Robker RL, et al. Peri-conception parental obesity, reproductive health, and transgenerational impacts. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, et al. Extreme obesity in pregnancy in the United Kingdom. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:989–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiddy DS, Hamilton-Fairley D, Bush A, et al. Improvement in endocrine and ovarian function during dietary treatment of obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1992;36:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clark AM, Ledger W, Galletly C, et al. Weight loss results in significant improvement in pregnancy and ovulation rates in anovulatory obese women. Hum Reprod 1995;10:2705–2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Homan GF, Davies M, Norman R. The impact of lifestyle factors on reproductive performance in the general population and those undergoing infertility treatment: a review. Hum Reprod Update 2007;13:209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Azziz R Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:321–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moran L, Tsagareli V, Norman R, et al. Diet and IVF pilot study: short-term weight loss improves pregnancy rates in overweight/obese women undertaking IVF. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;51:455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurzthaler D, Hadziomerovic-Pekic D, Wildt L, et al. Metformin induces a prompt decrease in LH-stimulated testosterone response in women with PCOS independent of its insulin-sensitizing effects. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2014;12:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rowan JA, Hague WM, Gao W, et al. Metformin versus insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2003–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumar P, Khan K. Effects of metformin use in pregnant patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Hum Reprod Sci 2012;5:166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feng L, Lin XF, Wan ZH, et al. Efficacy of metformin on pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2015;31:833–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zeng XL, Zhang YF, Tian Q, et al. Effects of metformin on pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palomba S, Falbo A, Orio F Jr et al. Effect of preconceptional metformin on abortion risk in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril 2009;92:1646–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cassina M, Dona M, Di Gianantonio E, et al. First-trimester exposure to metformin and risk of birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:656–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH, Balani J, et al. Metformin versus Placebo in Obese Pregnant Women without Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med 2016;374:434–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bell GA, Sundaram R, Mumford SL, et al. Maternal polycystic ovarian syndrome and offspring growth: the Upstate KIDS Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2018;72:852–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hanem LGE, Stridsklev S, Juliusson PB, et al. Metformin Use in PCOS Pregnancies Increases the Risk of Offspring Overweight at 4 Years of Age: Follow-Up of Two RCTs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103:1612–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hjorth-Hansen A, Salvesen O, Engen Hanem LG, et al. Fetal Growth and Birth Anthropometrics in Metformin-Exposed Offspring Born to Mothers With PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103:740–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jamal M, Gunay Y, Capper A, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass ameliorates polycystic ovary syndrome and dramatically improves conception rates: a 9-year analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:440–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Devlieger R, Guelinckx I, Jans G, et al. Micronutrient levels and supplement intake in pregnancy after bariatric surgery: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:e114192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johansson K, Cnattingius S, Naslund I, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2015;372:814–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rittenberg V, Seshadri S, Sunkara SK, et al. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2011;23:421–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Luke B, Brown MB, Missmer SA, et al. The effect of increasing obesity on the response to and outcome of assisted reproductive technology: a national study. Fertil Steril 2011;96:820–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moragianni VA, Jones SM, Ryley DA. The effect of body mass index on the outcomes of first assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril 2012;98:102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koning AM, Mutsaerts MA, Kuchenbecker WK, et al. Complications and outcome of assisted reproduction technologies in overweight and obese women. Hum Reprod 2012;27:457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferlitsch K, Sator MO, Gruber DM, et al. Body mass index, follicle-stimulating hormone and their predictive value in in vitro fertilization. J Assist Reprod Genet 2004;21:431–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chavarro JE, Ehrlich S, Colaci DS, et al. Body mass index and short-term weight change in relation to treatment outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril 2012;98:109–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Einarsson S, Bergh C, Friberg B, et al. Weight reduction intervention for obese infertile women prior to IVF: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2017;32:1621–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kort JD, Winget C, Kim SH, et al. A retrospective cohort study to evaluate the impact of meaningful weight loss on fertility outcomes in an overweight population with infertility. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1400–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sim KA, Dezarnaulds GM, Denyer GS, et al. Weight loss improves reproductive outcomes in obese women undergoing fertility treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Obes 2014;4:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moran LJ, Tsagareli V, Noakes M, et al. Altered Preconception Fatty Acid Intake Is Associated with Improved Pregnancy Rates in Overweight and Obese Women Undertaking in Vitro Fertilisation. Nutrients 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Espinos JJ, Polo A, Sanchez-Hernandez J, et al. Weight decrease improves live birth rates in obese women undergoing IVF: a pilot study. Reprod Biomed Online 2017;35:417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2985–3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mutsaerts MA, van Oers AM, Groen H, et al. Randomized Trial of a Lifestyle Program in Obese Infertile Women. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1942–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]