Summary:

Buccal fat contributes significantly to the contour of the face, but the contribution of buccal fat is often neglected on examination and in surgery. A case of isolated buccal fat removal is examined. Previous literature relevant to this case is discussed and the author’s experience from 10 subsequent lower facial rejuvenation surgeries combined with buccal fat reductions is presented with suggestions.

Much of the effort in surgical rejuvenation of the lower third of the face focuses on correcting contours of the neck and jawline/jowls. In some patients, though, prominence of buccal fat superior and posterior to the jowls can present another aesthetic problem. Fullness in this area detracts from the definition of the jawline and the zygomatic arch, potentially leading to a heavy appearance in the lower cheeks. The following case report highlights the aesthetic importance of the buccal fat pad and the ease with which it can be surgically addressed for marked improvement. The case is discussed in context of the existing literature on the topic and the author’s experience with buccal fat removal in 10 consecutive patients is offered.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old healthy woman presented with concern regarding fullness of her lower cheeks. She explained that this conspicuous fullness superior to the middle of the body of the mandible was a common feature in her family. She had previously undergone injection of 2 ml of deoxycholic acid once into each side. Four months following the injection, she noted no improvement and now presented for definitive surgical correction.

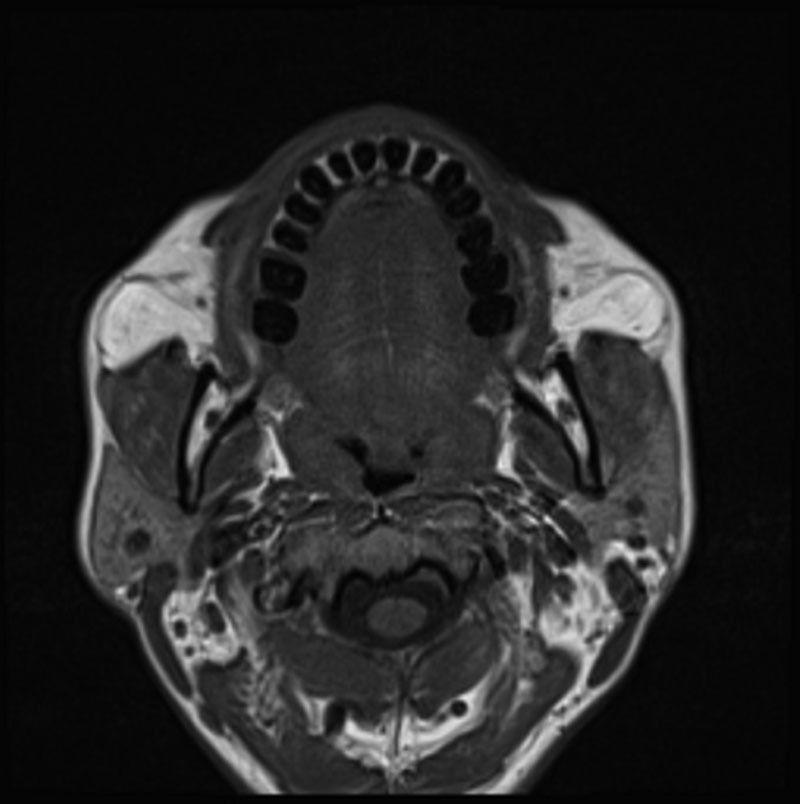

Examination demonstrated this soft prominence to be consistent with the location of the buccal fat pad. The patient had no significant skin laxity or jowling. A radiologist, she had ordered and MRI, which confirmed the presence of large buccal fat pads that were being pushed out even further laterally by the patient’s particularly thick masseter muscles (Fig. 1). The intraoral procedure for buccal fat removal and its risks were reviewed with the patient and she elected to proceed with surgery.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative T-1 Axial MRI image of a 39-year-old woman displaying fullness of facial cheeks and high buccal fat volume. Note association of buccal fat pads with buccinators muscle/gingivobuccal sulcus and the masseter muscles. Masseter muscles are also enlarged in this patient. Protrusion of buccal fat as the etiology of the bulges visible in the overlying cheek skin is obvious.

Following a preoperative oral solution wash with a chlorhexidine oral rinse (3M, Maplewood, Minn.), the patient was given general anesthesia with a laryngeal mask airway then injected with bupivacaine 0.25% with epinephrine 1:200,000 in each buccal sulcus. Before using cautery in the oropharynx, the FiO2 was 30% and it was assured that there was a good seal of the LMA cuff. After allowing time for vasoconstriction, an approximately 2 cm longitudinal incision was made with Bovie electrocautery 5 mm above the opening of Stensen’s duct, or approximately half-way between the opening of the duct and the gingivobuccal sulcus itself. After cautery incision exposed the buccinator muscle, spreading dissection with crile hemostatic forceps was performed through the buccinator fibers. Further spreading in a posterolateral direction exposed the buccal fat pad. The exposed fat was then expressed through the buccal sulcus incision with external pressure and amputated using cautery; removing a generous amount of fat until the external bulge was no longer visible (Fig. 2). The dissection and fat removal were essentially bloodless. The tip of an epinephrine 1:50,000 soaked gauze was placed in the incision while the other side was addressed. The same was performed contralaterally and the amounts of excised fat were compared. Once the amounts of removed fat and the contour of the cheeks both appeared equal, hemostasis was again assured. Incisions were closed with 4-0 chromic interrupted sutures and 4-0 chromic running lock sutures. This technique was essentially that described by Matarasso.1

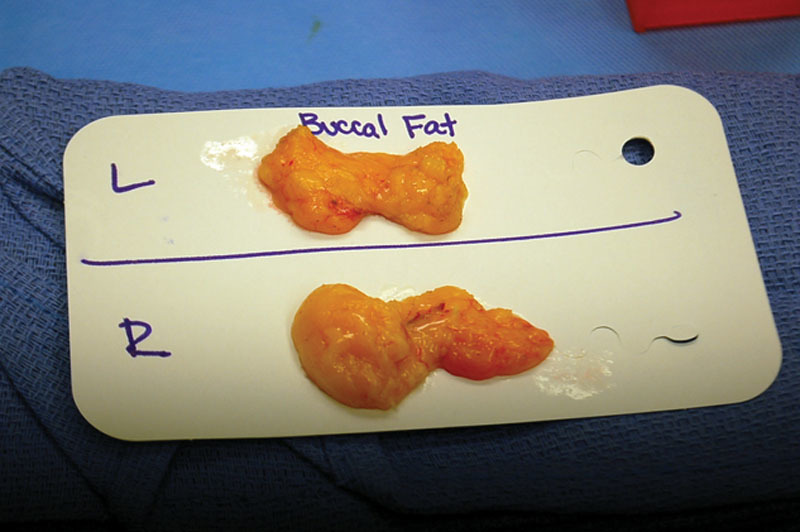

Fig. 2.

Resected buccal fat from the same 39-year-old female patient.

The patient was kept on clear liquids for the remainder of the operative day, then full liquids for 2 days, followed by a soft diet for one week. Recovery following the procedure progressed uneventfully. In visits 2 and 10 weeks following the procedure, the patient expressed extreme satisfaction with the outcome (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

The buccal fat pad contributes significantly to the contour of the cheek and face. Most commonly, its prominence is encountered during examination for facial rejuvenation surgery. In some patients, the buccal fat can cause unwanted fullness and, in more extreme cases, has been shown to pseudoherniate and result in the appearance of a sagging mass within the cheek.2,3 In this particular unique case, the buccal fat prominence was an isolated physical finding in a patient that was confirmed at presentation by MRI images.

Past literature has described several options for reduction and removal of the buccal fat pad. Newman et al4 described liposuction as a simple and safe method of removing buccal or jowl fat using his “buc-jowl” procedure. Stuzin et al5 argued that this method risks causing a gaunt appearance due to aggressive removal of buccal fat. Matarasso1 presented his procedure to excise the buccal fat pad and described the benefits it offers to patients; primarily contouring of the face that highlights the angularity of skeletal structure.

The buccal fat pad maintains a consistent volume throughout life and is less likely to fluctuate during growth or periods of weight loss/gain. Therefore, as a patient ages throughout adolescence and the face grows in size, the buccal fat mass remains nearly constant, losing relative volume.1,5,6 In the case of the aforementioned patient, she noted the fullness of her cheeks did not decrease with age, resulting from a large relative volume of buccal fat. Matarasso1 stated that patients with capacious faces such as this are good candidates for buccal fat pad removal.

In contrast, the patient’s definitive surgical buccal fat removal provided a simple and effective treatment with minimal morbidity. With a better appreciation for the power of the procedure in light of its simplicity, the authors have since incorporated it in 8 subsequent cases (Table 1) as an adjunct to other lower face rejuvenation surgeries.

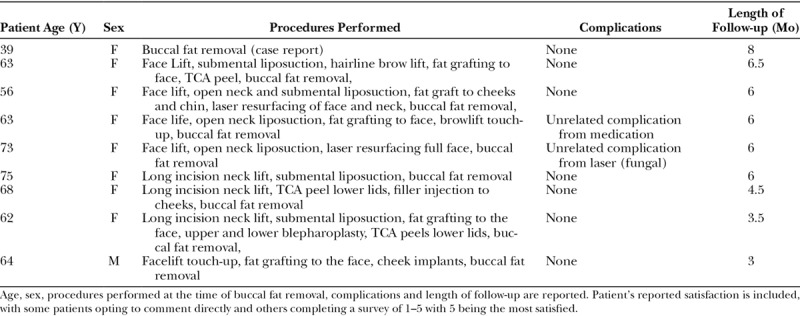

Table 1.

Detailed Information Regarding Each Patient Who Has Undergone Buccal Fat Removal

To identify appropriate candidates, Matarasso1 described his method of diagnosing buccal fat excess prominence by comparison of texture to adipose tissue and the tendency to reduce with upward displacement. Throughout this series of 10 cases, the authors have noted that, on physical examination, buccal fat should be assessed superior and posterior to the jowl area, most prominently at a location 3 cm superior to the mandibular notch, and just anterior to the anterior border of the masseter muscle. Balloting this area with the patient’s mouth open approximately 2 cm between the incisors will show whether buccal fat is contributing to fullness in this area of the cheek. A slow return of volume into the area after removing the finger, as might be expected with a viscous fluid, attests to the fullness being caused by buccal fat projection. In the authors’ experience, there is no practical reason to attempt to distinguish between buccal fat excess, displacement, herniation, or pseudoherniation. These semantics are less important than clinical appearance and potential improvement that can be gained through reduction of buccal fat.

It should be noted that this intraoral approach is not the only method of buccal fat removal. During facelifts, anterior cheek dissection over the buccal area allows easy access to buccal fat. In fact, this fat is visible anteriorly during a sub-SMAS dissection. As branches of the facial nerve are seen directly superficial to the buccal fat, gentle spreading between branches is required for expression of this fat. If fat is to be removed this way, it is the authors’ opinion that it is best performed after the completion of the SMAS dissection so that protruding fat does not get in the way of further visualization or dissection. Subcutaneous dissection can also be used to expose buccal fat through spreading, although we do not recommend this approach because nerve branches are not visible. Also, it has been observed that even a small defect in the anterior SMAS tends to widen with SMAS tightening or elevation, which can lead to protrusion of remaining fat. Suture closure of SMAS defects from spreading dissection is difficult at this anterior area as SMAS tissue is thin. Additionally, suturing of SMAS in this area may jeopardize underlying nerves due to difficult visualization. It should be noted that, in this series, such direct fat removal was not possible for patients in whom no cheek dissection was done. Certainly, further dissection anteriorly could have been utilized in these patients to access the buccal fat, although it is the authors’ experience that the relatively simple oral approach is not only faster and not threatening to the SMAS integrity, but also offers less exposure to nerve injuries as it avoids increased subcutaneous dissection far anteriorly where visualization is more difficult. Minimal subcutaneous dissection may also minimize risk of hematoma or seroma with less dead space (Figs. 3 and 4).

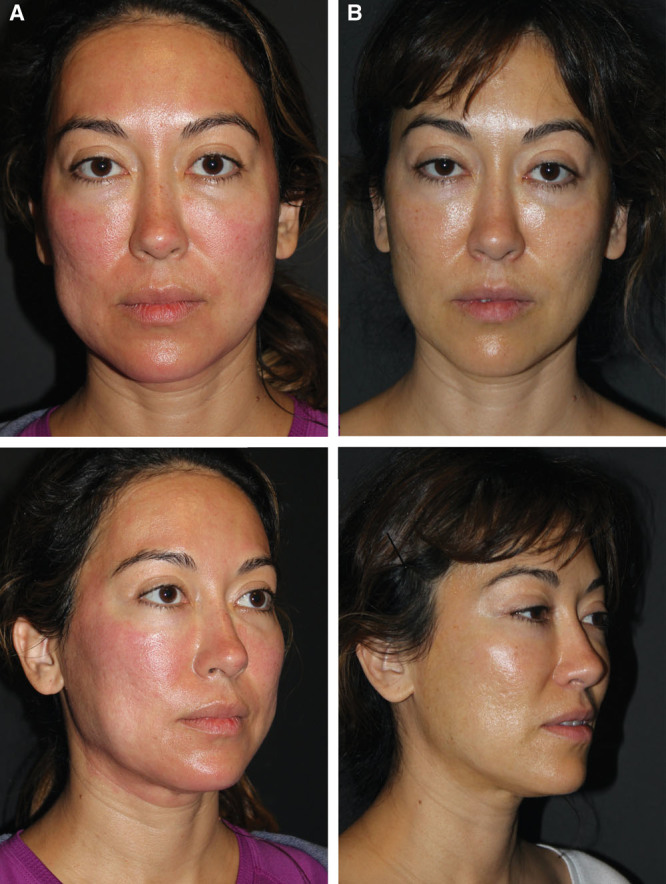

Fig. 3.

A, Preoperative and (B) postoperative photographs of the same 39-year-old woman displaying the result of isolated buccal fat resection 10 weeks following operation. Patient’s preoperative photograph shows erythema from an unrelated peel.

Fig. 4.

Excision of buccal fat using a 1-cm incision. Note similarity in appearance of buccal fat with that of yellow orbital fat.

Buccal fat removal is not appropriate for all patients. In fact, the near-ubiquitous use of facial fillers and the frequency of facial fat grafting demonstrate our modern emphasis on the need to replace facial volume. Furthermore, the common use of fat grafting during facelift procedures indicates the importance of volume restoration as a key part of comprehensive facial rejuvenation. It is not surprising, then, that buccal fat removal is not needed or desirable in thin or gaunt faces. In contrast, buccal fat removal is useful in fuller faces to create definition. Several of the author’s cases of buccal fat reduction also include fat grafting, performed in other areas of the face. In some instances, the removal of aesthetically overpowering buccal fat prominence can actually enhance the improvements achieved with fat grafting to other areas such as the malar eminences by more dramatically rejuvenating a “rectangular” face with a full lower third back toward a more youthful “V” shape.

The ease of achieving such improvements should be kept in mind when planning facial rejuvenation procedures. With improved appreciation for the location of the fat pad after spreading the buccinators muscle fibers, the procedure was found to be completed just as easily with a 1-cm incision. This incision is located at the second molar, 2/3 of the way from the buccal sulcus to the opening of Stensen’s duct. This location provides a generous cuff of mucosa for closure on the gingival side of the incision. The opening of the duct is first marked with ink, so that its location remains clearly visible throughout the procedure, after swelling and vasoconstriction from injection of local anesthetic distort the area. This smaller incision was initiated because stretching/lengthening of the 2 cm buccal sulcus incisions (as described by Matarasso) was noted in early cases. A medium toe-in Obweigeiser retractor works perfectly for this smaller incision and angle. Furthermore, closure of this incision can be quickly performed with 2 interrupted 4-0 chromic sutures. With decreased suturing time due to a shorter incision, operative time dropped to less than 20 minutes. In addition, the author has noted that rather aggressive fat pad removal is required in fuller faces to achieve a noticeable aesthetic improvement. Although most specimens removed have been in the range of 2–3 g, resections up to 4 g in fuller faces were performed with pleasing results. No evidence of over-resection has been observed postoperatively, corroborated by patients’ satisfaction with postoperative facial contours. The procedure has also not appeared to cause any additional edema, ecchymosis, and discomfort during recovery, seeming to add no extra morbidity to facial rejuvenation procedures, other than patients’ commenting about the buccal sulcus sutures. Additionally, the addition of buccal fat removal to facelift or necklift procedures does not affect postoperative care in any way other than the dietary restrictions of clear liquids on the day of surgery, then full liquids for 2 days, and then a soft diet for the rest of the first week.

Although not observed in any cases to date, potential complications include bleeding and over-resection of the buccal fat pad. It should be noted that follow-up was limited to 6 months in this study. Over-resection, particularly in thinner patients, could potentially lead to a wasted appearance, which can be difficult to treat except with fat grafting. Due to the adjacent facial nerve branches, nerve injury is of particular concern. For this reason, only buccal fat that freely is pushed/expressed into the oral cavity should be excised to avoid pulling adjacent tissue and nerves into the resection.

Based on this experience, the author now routinely assesses the buccal fat pad in facial rejuvenation consults. This has proven particularly important in patients with generally heavy faces, patients with excessive fullness in the lower third and patients who desire a “chiseled,” modelesque appearance. Because gaining this appreciation for the benefits of considering buccal fat reduction, which author performed buccal fat removal in 11 of his last 26 facelifts. In this way, attention to the buccal fat pad during consultation and consideration of this simple treatment can enhance outcomes and patient and physician satisfaction with little effect on operative time or morbidity.

In the experience described, a larger number of patients would be needed to demonstrate meaningful complication rates. A larger series should better elucidate general patient satisfaction, as well as frequency of volume depletion/over-resection among other potential complications. Additionally, this report is limited by the lack of objective, scalable results data. Also, longer-term follow-up would be beneficial in evaluating all outcomes. Likewise, postoperative assessments are subjective. The lack of anonymity in appraising patients’ satisfaction with results presents another limitation. In each case, patients were assessed for approval rating by the operating surgeon’s assistants, rather than through an anonymous, validated survey, which may bias their reported satisfaction.

CONCLUSIONS

The buccal fat pad contributes to fullness in the contour of the lower cheek. Surgical reduction of this fat can be easily and efficiently performed in isolation or as an adjunct to other facial aesthetic procedures with minimal added morbidity. The buccal fat pad should therefore be considered in consultations and kept in mind as an option in facial rejuvenation.

Footnotes

Published online 5 July 2019.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matarasso A. Managing the buccal fat pad. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26:330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matarasso A. Pseudoherniation of the buccal fat pad: a new clinical syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:723–730; discussion 731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matarasso A. Pseudoherniation of the buccal fat pad: a new clinical syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1716–1718; discussion 1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman J., Nguyen A, Anderson R. Liposuction of the buccal fat pad. Am J Consmet Surg. 1986;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Baker TM. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations (discussion). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002:109:2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, et al. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2509–2518; discussion 2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahai F. The Art of Aesthetic Surgery: Principles and Techniques. 2005:St. Louis, Mo.: Quality; Medical Publishing, Inc.; 1786. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson IT. Anatomy of the buccal fat pad and its clinical significance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:2059–2060; discussion 2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ablon G, Rotunda AM. Treatment of lower eyelid fat pads using phosphatidylcholine: clinical trial and review. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:422–427; discussion 428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasengschwandtner F. Injection lipolysis for effective reduction of localized fat in place of minor surgical lipoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2006; 26:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayan SH, Schlessinger J, Beer K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ATX-101 by treatment session: pooled analysis of data from the Phase 3 REFINE trials. Aesthet Surg J.2018;38:998–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanda S. Treatment of lipoma by injection lipolysis. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:135–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amber KT, Ovadia S, Camacho I. Injection therapy for the management of superficial subcutaneous lipomas. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:46–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamban AT. Noninvasive submental fat compartment treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(12 Suppl Anatomy and Safety in Cosmetic Medicine: Cosmetic Bootcamp):e1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]