Abstract

Classic galactosemia (CG) is a potentially lethal inborn error of galactose metabolism that results from deleterious mutations in the human galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) gene. Previously, we constructed a GalT−/− (GalT-deficient) mouse model that exhibits galactose sensitivity in the newborn mutant pups, reduced fertility in adult females, impaired motor functions, and growth restriction in both sexes. In this study, we tested whether restoration of hepatic GALT activity alone could decrease galactose-1 phosphate (gal-1P) and plasma galactose in the mouse model. The administration of different doses of mouse GalT (mGalT) mRNA resulted in a dose-dependent increase in mGalT protein expression and enzyme activity in the liver of GalT-deficient mice. Single intravenous (i.v.) dose of human GALT (hGALT) mRNA decreased gal-1P in mutant mouse liver and red blood cells (RBCs) within 24 h with low levels maintained for over a week. Repeated i.v. injections increased hepatic GalT expression, nearly normalized gal-1P levels in liver, and decreased gal-1P levels in RBCs and peripheral tissues throughout all doses. Moreover, repeated dosing reduced plasma galactose by 60% or more throughout all four doses. Additionally, a single intraperitoneal dose of hGALT mRNA overcame the galactose sensitivity and promoted the growth in a GalT−/− newborn pup.

Keywords: classic galactosemia, mRNA therapy, galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase, GALT, galactose-1 phosphate, galactose toxicity, inborn errors of metabolism, IEM, primary ovarian insufficiency, POI, ataxia, speech dyspraxia

Intravenous injection of human GALT mRNA in GalT−/− mice resulted in hepatic expression of active, long-lasting GALT enzyme, which rapidly and effectively eliminated gal-1P in liver and other peripheral tissues and significantly reduced plasma galactose. The augmentation of GALT activity also overcame the galactose sensitivity in the GalT−/− newborn pups.

Introduction

Classic galactosemia (CG) (OMIM 230400) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by deficiency of galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT, EC 2.7.7.12) activity (Figure 1).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 GALT is the second enzyme in the evolutionarily conserved galactose metabolic pathway and facilitates the simultaneous conversion of uridine diphosphoglucose (UDP-glucose) and galactose-1 phosphate (gal-1P) to uridine diphosphogalactose (UDP-galactose) and glucose-1 phosphate (Figure 1).6 Consequently, GALT deficiency leads to accumulation of gal-1P and deficiency of UDP-galactose in patient cells.7, 8 If untreated, CG can be lethal for the affected newborns.1, 5 Since the inclusion of this disease in the newborn screening panel in the U.S., neonatal mortality has decreased.9 The mainstay of treatment is the withdrawal of galactose from the diet.5 Yet, despite early and adequate dietary management, endogenous production of galactose/gal-1P persists10, 11 and many patients suffer long-term complications such as intellectual deficits in ≥6-year-olds (45% of patients); speech delay in ≥3-year-olds (56%), motor functions deficits (tremors and cerebellar ataxia) in ≥5-year-olds (18%), and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) (91%).12, 13 Decreased bone mineralization is increasingly recognized in pre-pubertal patients of either sex.14, 15, 16 Except for POI, which is nearly universal among affected females, there is great variability in manifestation among other long-term complications. Some attribute the variability to epigenetic factors, but none has been convincingly identified. The environmental and molecular mechanisms for these long-term complications remain enigmatic, although aberrant galactosylation of glycoproteins/lipids and inositol phospholipid signaling caused by chronic accumulation of toxic intermediates of the blocked galactose metabolic pathway have been proposed.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 There are currently no satisfactory treatments available to prevent or alleviate any of these complications.

Figure 1.

Disrupted Galactose Metabolism in Classic Galactosemia

(A) Under normal conditions, exogenous and endogenously produced galactose are phosphorylated by galactokinase (GALK1) to form galactose-1 phosphate (gal-1P). In the presence of galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT), gal-1P reacts with UDP-glucose to form glucose-1 phosphate and UDP-galactose. UDP-galactose can also be formed from UDP-glucose via the UDP galactose-4′-epimerase (GALE) reaction. (B) In Classic (GALT-deficiency) galactosemia, gal-1P accumulates and the production of UDP-galactose from the GALT reaction is blocked. Gal-1P is a competitive inhibitor of hUGP2 and therefore, UDP-glucose synthesis and its subsequent conversion to UDP-galactose (via the GALE reaction) are both diminished. Excess galactose accumulated in the GALT-deficient cells is catabolized to galactitol, which can be excreted in urine. Major organs affected in galactosemic patients are listed in the inset.

mRNA therapy is rapidly emerging as a new class of therapeutic modality with the potential to target proteins that cannot be treated by traditional enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) such as transmembrane and intracellular proteins. Recently, preclinical studies have evaluated the potential of systemically administered mRNA formulated in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to restore deficient intracellular proteins in liver for various inborn errors of metabolism.23, 24, 25, 26 Additional mRNA preclinical studies evaluated the use of liver as a protein-production depot to produce secreted therapeutic proteins.27, 28, 29 mRNA therapy has a number of unique features that make clinical translation promising for inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) such as galactosemia. One advantage of mRNA-based therapy over viral gene delivery is that mRNA does not transit to the nucleus, thereby mitigating insertional mutagenesis risks. mRNA provides transient, half-life-dependent protein expression, while avoiding constitutive gene activation and maintaining dose-responsiveness.

In this study, we investigated whether augmentation of liver GALT activity through mRNA therapy can normalize disease-relevant biomarkers and phenotypes in a mouse model of classic galactosemia. Our results showed that intravenous (i.v.) injection of human GALT mRNA in GalT−/− mice resulted in hepatic expression of active, long-lasting GALT enzyme, which rapidly and effectively eliminated gal-1P in liver and other peripheral tissues and significantly lowered plasma galactose. The restoration of GALT activity also overcame the galactose sensitivity in the GalT−/− newborn pups.

Results

Mouse GalT mRNA Expressed and Restored mGalT Activity in Fibroblasts Isolated from Galactosemic Patients

To test whether mouse GalT (mGalT) mRNA effectively expressed functional mGalT protein and enzyme activity in fibroblasts in vitro, human GALT-deficient patient fibroblasts were transfected with mGalT mRNA and control (GFP) mRNA. Western blot analysis showed that all transfected cells expressed higher level of mGalT protein (Figure 2A). The mGalT mRNA transfected cells expressed higher level of mGalT enzyme activity (32.9 ± 2 μmol/min/mg protein) than the control (Figure 2B). As shown in Figure 2C, the transfected GALT-deficient fibroblasts grew in medium containing galactose as the sole carbon source in a comparable way as that of patient cells in glucose-containing medium. This indicated that the reconstitution of mGalT activity in patient fibroblasts enabled the cells to metabolize galactose more efficiently.

Figure 2.

Expression and Activity of mRNA-Encoded mGalT in Patient Cells

(A) Western blot analysis of mGalT protein in galactosemic patient fibroblasts. (B) mRNA-encoded mGalT enzyme activities in galactosemic patient fibroblasts. (C) Reconstitution of mGalT activity in human galactosemic patient fibroblasts. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Hepatic Expression of Mouse GalT or Human GALT mRNA Restored mGalT/hGALT Activity in the Mouse Liver in 24 h after i.v. Injection

We performed a dose response and time course evaluation of mGalT/human GALT (hGALT) mRNA deliveries on GalT-deficient mice. The administration of three different, single doses of either hGALT or mGalT mRNA (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 mg/kg) led to a dose-dependent increase in GALT protein expression (19.7 ± 8.2%, 55.1 ± 11.0%, and 84.3 ± 22.1% of wild-type) and activity (39.3 ± 8.2%, 80.7 ± 7.4%, and 84.2 ± 21.7% of wild-type) in the liver of GALT-deficient mice (basal activity 0% for both protein and activity) (data not shown). Figure 3A shows that administration of either mGalT or hGALT mRNA at 0.5 mg/kg in the mutant mice resulted in hepatic expression of mGalT and hGALT protein at about 84% and 54%, respectively, of wild-type level in normal mouse liver. This translated to 84% and 45% of wild-type activity, respectively, in the mutant mouse liver 24 h after i.v. injection (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Expression and Activity of mGalT or hGALT in GalT-Deficient Mouse Liver 24 h after i.v. Injection

(A) Western blot analysis of mRNA-encoded mouse and human GALT proteins in GalT-deficient mouse liver. (B) mRNA-encoded mouse GalT and human GALT enzyme activities in GalT-deficient mouse liver. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

To assess the half-life of mRNA-encoded mouse GalT in the GalT-deficient mouse liver, we administered 0.5 mg/kg mGalT mRNA to the mutant mouse by i.v. injections and monitored the mGalT protein expression and activity consecutively for 14 days. As shown in Figure 4A, we determined that the half-life of mGalT protein, as well as the expressed mGalT enzyme activity, after a single mRNA delivery was approximately 4 days (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Single i.v. Dose of mGalT mRNA Resulted in Long Half-Lived mGalT Protein and Activity in Liver and Reduced Hepatic and Tissue Gal-1P Accumulation

(A) Western blot analysis of mRNA-encoded mouse GalT protein in GalT-deficient mouse liver over a course of 2 weeks after a single i.v. dose. (B) mRNA-encoded mouse GalT enzyme activity in GalT-deficient mouse liver over a single i.v. dose. (C) Galactose-1 phosphate levels in liver at different time points after single i.v. injection of mGalT mRNA. (D) Galactose-1 phosphate levels in RBCs at different time points after single i.v. injection of mGalT mRNA. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 compared to correspondent control mRNA group from one-way-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Single mGalT mRNA Dosage Reduced Hepatic and Tissue Gal-1P for Over a Week

In our previous studies, Tang and coworkers reported that the homozygous GalT gene-trapped mice accumulated significantly elevated level of gal-1P in red blood cells (RBCs) when they are fed with normal chow.30 To determine whether the systemic administration of mGalT mRNA restores the hepatic functions and reduces the blood and tissue gal-1P accumulation in the absence of galactose challenge, we i.v. injected GalT−/− mice with a single dose (0.5 mg/kg) of mGalT mRNA and collected samples at 2, 6, 10, and 14 days post injection. We observed that a single i.v. dose (0.5 mg/kg) of mGalT mRNA decreased gal-1P in RBCs (−70%, from 137.7 ± 19.5 to 41.8 ± 17.1 nmol/100 μL RBCs) and liver (−82%, from 22.8 ± 13.6 to 4.2 ± 1.5 μmol/g wet weight), respectively, within 24 h with low levels maintained for more than a week (Figures 4C and 4D).

Repeated i.v. Dosing of hGALT mRNA Reduced Blood and Tissue Gal-1P and Plasma Galactose Accumulation

To evaluate the effect of hepatic expression of hGALT mRNA on the level of accumulated blood and tissue gal-1P and plasma galactose, we administered repeated dosing of hGALT mRNA by i.v. injection biweekly for 8 weeks at 0.5 mg/kg with either GFP or hGALT mRNA. Repeated i.v. injections resulted in a trend of gal-1P reduction in RBCs throughout all four doses compared to PBS control group but significant reduction of RBC gal-1P levels compared to control mRNA group following 1st, 3rd, and 4th dose administration. Moreover, repeat i.v. injections significantly diminished gal-1P levels in liver by approximately 72% (Figure 5A, i and ii). Likewise, hGALT mRNA also effectively and significantly reduced the ovary and brain gal-1P in the treated mice compared to the control (Figure 5A, iii and iv). Moreover, repeated dosing decreased plasma galactose by more than 60% by the end of four doses (p < 0.05) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Repeated IV Dose of hGALT mRNA Reduced RBCs, Liver, Ovary, and Brain Gal-1P Accumulation and Decreased Plasma Galactose and Galactitol Accumulation

(A) Galactose-1 phosphate levels in (i) RBCs, (ii) liver, (iii) ovary, and (iv) brain after repeated four doses of human GALT mRNA. (B) Plasma galactose levels after repeated doses of hGALT mRNA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 compared to correspondent PBS group and #p < 0.05 compared to control mRNA group obtained from Dunn’s multiple comparisons test following a Kruskal-Wallis test (A, i and B). *p < 0.05 compared to PBS group from one-way-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (A, ii, iii, and iv). # p < 0.05 compared to control mRNA group from one-way-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (A, ii, iii, and iv).

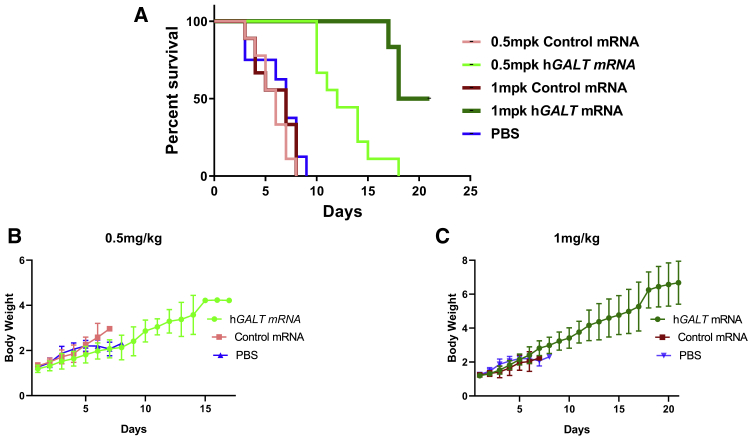

Single i.p. Dose of hGALT mRNA Overcame Neonatal Galactose Sensitivity and Promoted Growth

Infants with classic galactosemia usually die shortly after birth if the milk is not withdrawn in time. In our previous study on GalT-deficient mouse model, we reported that when the lactating homozygous GalT-/- mothers were fed with high galactose diet, soon after the homozygous GalT−/− pups were born, over 70% of the new born pups died before weaning.30 Here we repeated the same experiment, except we injected the homozygous GalT-/- pups with control GFP mRNA, PBS, or hGALT mRNA soon after their birth. We observed a high mortality rate within 1 week for the pups injected with either GFP mRNA or PBS. In contrast, all GalT−/− pups treated with a single dose of 0.5 mg/kg hGALT mRNA survived for 10–14 days. Interestingly, in the cohort of study in which the GalT−/− pups were treated with 1 mg/kg hGALT mRNA survived throughout the study period (i.e., 3 weeks) (Figure 6A). In addition, the treated mice gained significant body weight compared to the PBS and control mRNA group (Figures 6B and 6C).

Figure 6.

Single i.p. Dose of Human GALT mRNA Reversed Neonatal Galactose Sensitivity and Promoted Growth

(A) Percentage survival analysis of PBS, control GFP mRNA, and hGALT mRNA treated galactose intoxicated GalT-deficient pups. (B and C) Comparison of body weight among mutant pups treated with PBS, control GFP mRNA, and hGALT mRNA. The Mantel-Cox log rank test was used to compare the survival rates of pups in different groups (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

It has been more than a century since classic galactosemia, an inborn error of metabolism (IEM) with an incidence of 1 in 40,000 live births, was first documented,31 and over four decades since its biochemical basis elucidated.1, 32 Despite the life-saving dietary management during the neonatal period, the continued lack of safe and effective therapies for the long-term debilitating complications has taken a heavy toll in the quality of life of over 2,000 patients worldwide and their caregivers.33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Traditional therapeutic strategies for IEMs focused on ERT and substrate reduction therapy. While ERT enjoys some successes in lysosomal storage diseases,41 the CNS pathology associated with the diseases remain a challenge because of the inability of the enzymes to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB).42 Therefore, the efficacy of ERT in treating the neurological complications of galactosemia could be limited. Substrate reduction therapy through galactose restriction has been instrumental in averting the lethality during the neonatal period of the affected patients, but the galactose-restricted diet alone is insufficient to prevent the long-term complications. Other emerging experimental therapeutic approaches for galactosemia include the targeting of galactokinase43, 44 and aldose reductase,45 as well as endoplasmic reticulum stress46, 47 by small molecule inhibitors, but none of them have reached the stage for clinical trials at this moment.

Although the environmental and molecular mechanisms for the long-term complications associated with classic galactosemia have not been fully delineated, none will debate that the disease is caused by deleterious mutations in the GALT genes, which result in the complete absence of cellular GALT enzyme activity. In this study, we pursued a nucleic acid-based therapeutic strategy, where we delivered human GALT (hGALT) mRNA into the liver of a GalT-deficient mouse at which the hGALT mRNA will be translated and form functional GALT enzyme. We hypothesized that upon hepatic hGALT gene expression, the liver will act as a “sink” to metabolize all the excess galactose in the blood that flows through the organ. A gradient of galactose between the blood in circulation and the peripheral tissues will then be created, and this will allow the excess galactose built up in the GALT-deficient cells to transport out to the bloodstream via this gradient and be metabolized by the GALT+ve liver cells. The overall results will be the diminished production and accumulation of toxic galactose metabolites in the peripheral tissues in organs such as ovary and brain. In fact, Otto and coworkers reported the normalization of galactose metabolism in a galactosemic patient after liver transplant.48 Moreover, if we compare classic galactosemia with another inherited metabolic disorder called phenylketonuria (PKU), one should not be surprised by the role played by the liver in whole-body metabolism. In PKU, the enzyme involved—phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH)—is almost exclusively expressed in the liver. However, its deficiency (in liver) could lead to accumulation of phenylalanine in the CNS and cause brain damage, indicating that the liver has the capacity to metabolize excess phenylalanine from the diet or produced through natural protein turnover in distant organs. Last but not least, we believe this strategy offers the advantage of directly addressing the root cause of the galactosemia by replenishing the absent GALT activity.

To test our overall hypothesis and to validate our GALT mRNA delivery system, we began by establishing the successful translation of the transfected mGalT mRNA in patient fibroblasts that are devoid of GALT activity (Figure 2A). We also demonstrated that the translated mGalT mRNA expressed recused galactose-induced death and allowed the growth of the transfected patient fibroblasts at a rate comparable to normal fibroblasts (Figure 2C).

After we confirmed the functional expression of the transfected mGalT mRNA in the patient fibroblasts, we initiated in vivo studies of i.v. GALT mRNA delivery in the GalT−/− (GalT-knockout [KO]) mice (Figure 3). We confirmed the expression of the mGalT and hGALT enzymes and activities in the livers of the mutant animals despite the lower expression level of hGALT, probably due to less-efficient translation of the human GALT in mRNA in mouse liver. The expression level of mGalT is comparable to the level seen in wild-type animals in terms of both abundance and enzyme activity (Figure 3). Following this, we examined the in vivo half-lives of the expressed mGalT protein and activity in liver in a single i.v. dose study. As shown in Figures 4A and 4B, the expressed mGalT enzyme and activity have half-lives of approximately 4 days, and the decline of enzyme activity mirrored the decay in protein abundance.

Next, we explored the in vivo effects of mouse GalT (mGalT) mRNA on biomarkers relevant to galactosemia. As revealed in Figures 4C and 4D, we showed that a single i.v. dose (0.5 mg/kg) of mGalT mRNA was sufficient to reduce the levels of gal-1P in liver and RBCs. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test showed that the differences between control and mGalT mRNAs are significant up to day 6 and day 10 in liver and RBCs, respectively. Yet, unpaired t test extended the significance to day 14. Interestingly, we observed a trend of gal-1P reduction in the liver in mice treated with control mRNA formulated with LNP, which was later found in the repeat-dosing study (Figure 5A, ii). The mechanism of this reduction is currently unclear. This effect appears to be seen in the liver, but not in brain and ovary as LNP is mainly delivered into liver (Figure 5A, iii and iv).

The fact that we saw a significant reduction of RBC gal-1P in the treated animals supported our initial hypothesis that hepatic GALT expression could help metabolize excess galactose produced and/or accumulated in peripheral tissues. To further support this hypothesis, we examined the gal-1P levels in other tissues after four bi-weekly doses of hGALT mRNA. Although we only witnessed a trend of gal-1P reduction in RBCs compared to PBS control group in this multi-dose study (Figure 5A, i), we definitively saw significant reduction of gal-1P in liver, ovary, and brain at the end of four doses (Figure 5A, ii, iii, and iv). The reduction of gal-1P in these organs has great implications as they are all affected in galactosemia. Besides, we saw more than 50% decrease in plasma galactose (Figure 5B). We have indeed observed less efficiency of gal-1P reduction in repeat-dosing study compared to single-dose study (Figures 4C and 4D). One explanation could be the use of hGALT mRNA for repeat-dosing study, which in single-dose study has shown lower expression compared to mGalT in mice (Figure 3).

In addition to biochemical markers like galactose and gal-1P, we tested the efficacy of hGALT mRNA in preventing the lethal consequence of galactose sensitivity, the most severe and acute disease phenotype, in the neonatal mutant pups. We demonstrated in Figure 6A a dose-dependent effect for the hGALT mRNA in the rescue of the pups. We also showed that the single dose of hGALT mRNA given allowed the pups to grow (Figures 6B and 6C). At the end of 21 days, the body weights of the treated pups reached approximated 62% of those of normal pups.30 Judging from the fact that it is a single-dose study and the half-life of the GALT mRNA is approximately 4 days (Figure 4), we believe the results are highly significant and pave the way to evaluate the efficacy of this treatment modality against other disease-relevant phenotypes such as motor impairment, cognition, and subfertility. To accomplish such goals, we plan to conduct experiments that include, but are not limited to, rotarod testing, maze solving, and extensive breeding trials in the future.

Although immunogenicity was not evaluated in the present study, GalT KO mice that received repeated hGALT mRNA administration showed significant reduction of plasma galactose following 2nd, 3rd, and 4th injections. Moreover, decreased Gal-1P levels have been observed in liver, ovary, and brain following four injections. Taken together, these data suggest that hGALT mRNA formulated with LNP remained effective in GalT KO mice following repeated dosing. This is consistent with our previous studies that demonstrated consistent protein expression, sustained pharmacology, and durable functional benefits of repeat injections in mouse, rat, and non-human primate.23, 24, 49, 50 In addition, inflammatory markers and anti-drug antibodies have been measured in a comparable 5-week repeat-dose study, and no increase of plasma cytokines (interleukin-6 [IL-6], interferon-γ [IFN-γ], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], and IL-1β) or anti-drug antibody levels were observed following 3 and 5 weekly i.v. bolus injections compared to mice receiving weekly injections of PBS.23 Finally, minimal elevations in inflammatory markers including complement and cytokines have been observed in repeat dose toxicology studies conducted in cynomolgus monkeys receiving mRNA encapsulated with a similar LNP (1 mg/kg).27

Despite the promising results shown in the liver, we are fully aware that we did not see complete normalization of biomarkers (e.g., gal-1P) in the peripheral tissues. This could be explained by the fact that even though liver is a major organ for galactose metabolism, continued endogenous production of galactose occurs in all tissues. Therefore, the dosage, as well as the dosing regimen we used in this pilot study, can use further optimization in the future to better match the galactose production rates in other organs. Interestingly, a recent report from Yuzyuk and coworkers suggested that it is not necessary to have total elimination of gal-1P in order to achieve favorable long-term outcome in the patients.51 In their study, they showed that patients with RBC gal-1P lower than 2 mg/dL have a significantly lower incidence of long-term complications (p = 0.01). Nevertheless, our work presented here represents a novel and promising nucleic-acid-based therapy to address the unmet medical needs of the patients with classic galactosemia.

Conclusions

Intravenous injection of human GALT mRNA in GalT−/− mice resulted in hepatic expression of active, long-lasting GALT enzyme, which rapidly and effectively eliminated gal-1P in liver and other peripheral tissues and significantly lowered plasma galactose. The restoration of GALT activity also overcame the galactose sensitivity in the GalT−/− newborn pups.

Materials and Methods

Preparation and Formulation of mRNA

mRNA was synthesized and formulated in LNPs as described previously.52, 53, 54 The same biodegradable, ionizable LNP described in our previous studies27 was used in the current set of studies. The full sequences of hGALT mRNA and mGalT mRNA are specified in Figures S1 and S2, respectively. Briefly, mRNA was synthesized in vitro by T7 RNA polymerase-mediated transcription with 5-methoxy UTP in place of UTP. The linearized DNA template contains the 5′ and 3′ UTRs, open reading frame (ORF), and the poly-A tail. The mRNA was produced with cap1 to improve translation efficiency. After purification, the mRNA was diluted in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5) and mixed with lipids dissolved in ethanol (50:10:38.5:1.5; ionizable:helper:structural:polyethyleneglycol) at a ratio of 3:1 (aqueous:ethanol). The final product was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and stored in pre-sterilized vials frozen until use. The mRNAs were tested for purity and capping efficacy and were found to be >70% and >90%, respectively. All formulations were tested for particle size, RNA encapsulation, and endotoxin and were found to be <100 nm in size, with >80% encapsulation, and <10 EU/mL endotoxin.

Mouse Model of Galactosemia

All animal studies were conducted in full compliance with the guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. GalT-deficient mice used in this study were constructed as previously described and were fed with normal chow at all times since weaning.30 All mice were confirmed by genotyping (molecular and biochemical) using previously published protocols.30 Both male and female were used for the present study and were uniformly distributed in each experiment group.

mRNA Administration

8-week-old GalT-deficient mice were injected i.v. with 100 μL of sterile LNPs provided by Moderna Therapeutics. Different dosages at (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 mg/kg) were used at designated durations. LNPs were diluted in sterile PBS at specified concentrations. One day prior to injection, 40 μL of blood samples were collected and serum and RBCs were prepared. 24 h post injection, mice were sacrificed and livers, brains, ovaries, and blood were collected to analyze the GALT expression and activity.

Assessment of Plasma Galactose and Gal-1P in Tissues

GalT-deficient mice were injected i.v. with 100 μL of sterile LNPs. Blood was collected 1 day prior to injection, as well as 2, 6, 10, and 14 days post injection. At 2, 6, 10, and 14 days post injection, mice were sacrificed and livers, brains, RBCs, and serum were collected. Serum galactose was determined by GC-MS (see below). Gal-1P extracted from livers, brains, ovaries, and RBCs was determined by GC-MS (see below). To understand the effect of repeated dosage of mRNA, we i.v. injected 8-week-old GalT-deficient mice with 100 μL of sterile LNPs (0.5 mg/kg) bi-weekly for 8 weeks. Blood was collected twice a week to monitor blood galactose and gal-1P in RBCs. At the end of 8 weeks, mice were sacrificed and livers, brains, ovaries, RBCs, and serum were collected analyzed for RBC gal-1P accumulation and plasma galactose buildup.

Assessment of Galactose Sensitivity in Human GALT mRNA Administered GalT -Deficient Pups

To determine whether GALT mRNA rescues GalT-deficient pups challenged with galactose, we injected both male and female pups intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 10 μL of sterile LNPs (0.5 and 1 mg/kg) within 24 h of birth. 10 μL PBS and (0.5 and 1 mg/kg) GFP mRNA were administered as controls. The diet feeding to the nursing dam was switched from regular to high-galactose (20%) chow 24 h after injection. Pups were carefully observed on a daily basis for weight gain, feeding, and activity. The mice were weighed daily and the survival rate and lifespan were recorded.

Quantification GALT Enzyme Activity by HPLC Based Enzymatic Assay

GALT activity was determined as described previously.55 Briefly, 30 μg liver homogenate is incubated with 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 40 μM DTT, 6 mM Gal-1P, 125 mM glycine, 1.5 mM UDP at 37°C for 5 min before starting the enzyme reaction by adding Gal-1P (60 mM) for 30 min with a heating block. GALT enzyme reactions are terminated by the adding 150 μL of ice-cold 3.3% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and vortexing. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C, the supernatant was transferred to a new set of tubes. The mixture was neutralized by the adding 8 μL ice-cold 5 M potassium carbonate. The samples were kept on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C. Chromatographic separation and quantification is accomplished with a high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a quaternary-pump, a multi-sampler, a thermostated column-compartment, and a SUPELCOSIL LC-18-S column (150 mm × 3.0 mm, particle size 5 μm), all used according to the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

Livers were lysed in lysis buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (S8830, Sigma-Aldrich). Homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min and supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA). For immunoblotting, lysates (30 μg protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE. Membranes were incubated with GALT (ab178406, Abcam), α-tubulin (ab80779, Abcam), and GAPDH (ab105430, Abcam) antibodies. Membranes were imaged using the Li-COR imaging platform.

Quantification of Gal-1P and Galactose and by GC-MS

Gal-1P and galactose were measured by GC-MS as described previously.56 Briefly, tissue (liver, brain, and ovary) lysates were created by homogenizing weighed tissue with 0.2–1 mL HPLC grade water. Crude lysates were agitated for 30 min at 4°C before centrifugation (12,500 × g at 4°C for 10 min) and supernatants were collected. Hemolysates were created by adding 20 μL HPLC grade water to 10 μL RBCs and deproteinized with 0.9 mL HPLC grade methanol. Plasma (10 μL) were treated with 0.5 mL methanol. Tissue lysates (50 μL/ 25 μL liver, 100 μL/25 μL brain, and 50 μL/40 μL ovary; Gal-1P and galactose, respectively) were deproteinized with 0.5 mL methanol. The mixture was vortexed, centrifuged at 12,5000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the clear supernatant was transferred and dried. For Gal-1P, dried samples were trimethylsilyated with 120 μL N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA), 1% trimethylsilyl chloride (TMSC), and pyridine in equal volumes, incubated (90°C, 30 min), and centrifuged (12,500 × g, 4°C, 3 minutes). The liquid phase was transferred to suitable glass vials for GC-MS analysis. For galactose, dried samples were trimethylsilyated with 2.1 mg hydroxylamine hydrochloride in 100 μL pyridine and incubated (90°C, 30 min). 75 μL acetic anhydride were added to each sample and incubated for an additional h at 90°C. 1 mL of HPLC grade water and 0.32 mL methylene chloride were added and vortexed to mix. Mixtures were centrifuged (12,500 × g, 4°C, 3 min) and the lower liquid phase was transferred and dried. The resulting sample was reconstituted with 100 μL ethylacetate and transferred to suitable glass vials for GC-MS analysis.

Author Contributions

B.B., D.A., P.G.V.M., and K.L. designed the experiments. B.B., D.A., V.N., and C.D. performed the experiments. B.B., D.A., V.N., P.G.V.M., and K.L. analyzed the data. B.B., D.A., V.N., and K.L. wrote the manuscript, and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

D.A., V.N., C.D., and P.G.V.M. are employees of, and receive salary and stock options from, Moderna, Inc.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.09.018.

Contributor Information

Paolo G.V. Martini, Email: paolo.martini@modernatx.com.

Kent Lai, Email: kent.lai@hsc.utah.edu.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Isselbacher K.J., Anderson E.P., Kurahashi K., Kalckar H.M. Congenital galactosemia, a single enzymatic block in galactose metabolism. Science. 1956;123:635–636. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3198.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridovich-Keil J.L. Galactosemia: the good, the bad, and the unknown. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;209:701–705. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyfield L., Reichardt J., Fridovich-Keil J., Croke D.T., Elsas L.J., 2nd, Strobl W., Kozak L., Coskun T., Novelli G., Okano Y. Classical galactosemia and mutations at the galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase (GALT) gene. Hum. Mutat. 1999;13:417–430. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:6<417::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry G.T., Segal S., Gitzelmann R. Disorders of Galactose Metabolism. In: Fernandes J., Saudubray M., van den Berghe G., Walter J.H., editors. Inborn Metabolic Diseases - Diagnosis and Treatment. Fourth Edition. Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal S., Berry G.T. Disorders of galactose metabolism. In: Scriver C.R., Beaudet A.L., Sly W.S., Valle D., editors. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Diseases. Volume I. McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 967–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leloir L.F. The enzymatic transformation of uridine diphosphate glucose into a galactose derivative. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1951;33:186–190. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(51)90096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gitzelmann R. Galactose-1-phosphate in the pathophysiology of galactosemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1995;154(7, Suppl 2):S45–S49. doi: 10.1007/BF02143803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai K., Langley S.D., Khwaja F.W., Schmitt E.W., Elsas L.J. GALT deficiency causes UDP-hexose deficit in human galactosemic cells. Glycobiology. 2003;13:285–294. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye C.I., Accurso F., La Franchi S., Lane P.A., Hope N., Sonya P., G Bradley S., Michele A L.P., Committee on Genetics Newborn screening fact sheets. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e934–e963. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry G.T., Moate P.J., Reynolds R.A., Yager C.T., Ning C., Boston R.C., Segal S. The rate of de novo galactose synthesis in patients with galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;81:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry G.T., Nissim I., Lin Z., Mazur A.T., Gibson J.B., Segal S. Endogenous synthesis of galactose in normal men and patients with hereditary galactosaemia. Lancet. 1995;346:1073–1074. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91745-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waggoner D., Buist N.R.M. Long-term complications in treated galactosemia - 175 U.S. cases. Int. Pediatr. 1993;8:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waggoner D.D., Buist N.R.M., Donnell G.N. Long-term prognosis in galactosaemia: results of a survey of 350 cases. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1990;13:802–818. doi: 10.1007/BF01800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batey L.A., Welt C.K., Rohr F., Wessel A., Anastasoaie V., Feldman H.A., Guo C.Y., Rubio-Gozalbo E., Berry G., Gordon C.M. Skeletal health in adult patients with classic galactosemia. Osteoporos. Int. 2012;24:501–509. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panis B., Forget P.P., van Kroonenburgh M.J., Vermeer C., Menheere P.P., Nieman F.H., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Bone metabolism in galactosemia. Bone. 2004;35:982–987. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Hamming S., van Kroonenburgh M.J., Bakker J.A., Vermeer C., Forget P.P. Bone mineral density in patients with classic galactosaemia. Arch. Dis. Child. 2002;87:57–60. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry G.T. Is prenatal myo-inositol deficiency a mechanism of CNS injury in galactosemia? J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:345–355. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhat P.J. Galactose-1-phosphate is a regulator of inositol monophosphatase: a fact or a fiction? Med. Hypotheses. 2003;60:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(02)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlwood J., Clayton P., Keir G., Mian N., Winchester B. Defective galactosylation of serum transferrin in galactosemia. Glycobiology. 1998;8:351–357. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coss K.P., Hawkes C.P., Adamczyk B., Stöckmann H., Crushell E., Saldova R., Knerr I., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Monavari A.A., Rudd P.M., Treacy E.P. N-glycan abnormalities in children with galactosemia. J. Proteome Res. 2014;13:385–394. doi: 10.1021/pr4008305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ornstein K.S., McGuire E.J., Berry G.T., Roth S., Segal S. Abnormal galactosylation of complex carbohydrates in cultured fibroblasts from patients with galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase deficiency. Pediatr. Res. 1992;31:508–511. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199205000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prestoz L.L., Couto A.S., Shin Y.S., Petry K.G. Altered follicle stimulating hormone isoforms in female galactosaemia patients. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1997;156:116–120. doi: 10.1007/s004310050568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An D., Schneller J.L., Frassetto A., Liang S., Zhu X., Park J.S., Theisen M., Hong S.J., Zhou J., Rajendran R. Systemic Messenger RNA Therapy as a Treatment for Methylmalonic Acidemia. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3548–3558. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang L., Berraondo P., Jericó D., Guey L.T., Sampedro A., Frassetto A., Benenato K.E., Burke K., Santamaría E., Alegre M. Systemic messenger RNA as an etiological treatment for acute intermittent porphyria. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1899–1909. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0199-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prieve M.G., Harvie P., Monahan S.D., Roy D., Li A.G., Blevins T.L., Paschal A.E., Waldheim M., Bell E.C., Galperin A. Targeted mRNA Therapy for Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:801–813. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roseman D.S., Khan T., Rajas F., Jun L.S., Asrani K.H., Isaacs C., Farelli J.D., Subramanian R.R. G6PC mRNA Therapy Positively Regulates Fasting Blood Glucose and Decreases Liver Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of Glycogen Storage Disease 1a. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabnis S., Kumarasinghe E.S., Salerno T., Mihai C., Ketova T., Senn J.J., Lynn A., Bulychev A., McFadyen I., Chan J. A Novel Amino Lipid Series for mRNA Delivery: Improved Endosomal Escape and Sustained Pharmacology and Safety in Non-human Primates. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeRosa F., Guild B., Karve S., Smith L., Love K., Dorkin J.R., Kauffman K.J., Zhang J., Yahalom B., Anderson D.G., Heartlein M.W. Therapeutic efficacy in a hemophilia B model using a biosynthetic mRNA liver depot system. Gene Ther. 2016;23:699–707. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramaswamy S., Tonnu N., Tachikawa K., Limphong P., Vega J.B., Karmali P.P., Chivukula P., Verma I.M. Systemic delivery of factor IX messenger RNA for protein replacement therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E1941–E1950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619653114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang M., Siddiqi A., Witt B., Yuzyuk T., Johnson B., Fraser N., Chen W., Rascon R., Yin X., Goli H. Subfertility and growth restriction in a new galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) - deficient mouse model. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:1172–1179. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goppert F. Galaktosurie nach Milchzuckergabe bei angeborenem, familiaerem chronischem Leberleiden. Klin. Wochenschr. 1917;54:473–477. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalckar H.M., Anderson E.P., Isselbacher K.J. Galactosemia, a congenital defect in a nucleotide transferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1956;20:262–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(56)90285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosch A.M., Grootenhuis M.A., Bakker H.D., Heijmans H.S., Wijburg F.A., Last B.F. Living with classical galactosemia: health-related quality of life consequences. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e423–e428. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert C., Boneh A. The impact of galactosaemia on quality of life--a pilot study. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2004;27:601–608. doi: 10.1023/b:boli.0000042957.98782.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Haskovic M., Bosch A.M., Burnyte B., Coelho A.I., Cassiman D., Couce M.L., Dawson C., Demirbas D., Derks T. The natural history of classic galactosemia: lessons from the GalNet registry. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019;14:86. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panis B., Gerver W.J., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Growth in treated classical galactosemia patients. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2007;166:443–446. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ten Hoedt A.E., Maurice-Stam H., Boelen C.C., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., van Spronsen F.J., Wijburg F.A., Bosch A.M., Grootenhuis M.A. Parenting a child with phenylketonuria or galactosemia: implications for health-related quality of life. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:391–398. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9267-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gubbels C.S., Maurice-Stam H., Berry G.T., Bosch A.M., Waisbren S., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Grootenhuis M.A. Psychosocial developmental milestones in men with classic galactosemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:415–419. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9290-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bosch A.M., Maurice-Stam H., Wijburg F.A., Grootenhuis M.A. Remarkable differences: the course of life of young adults with galactosaemia and PKU. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2009;32:706. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffmann B., Dragano N., Schweitzer-Krantz S. Living situation, occupation and health-related quality of life in adult patients with classic galactosemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012;35:1051–1058. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9469-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lachmann R.H. Enzyme replacement therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2011;23:588–593. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834c20d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rombach S.M., Smid B.E., Bouwman M.G., Linthorst G.E., Dijkgraaf M.G., Hollak C.E. Long term enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease: effectiveness on kidney, heart and brain. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013;8:47. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu L., Tang M., Walsh M.J., Brimacombe K.R., Pragani R., Tanega C., Rohde J.M., Baker H.L., Fernandez E., Blackman B. Structure activity relationships of human galactokinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wierenga K.J., Lai K., Buchwald P., Tang M. High-throughput screening for human galactokinase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Screen. 2008;13:415–423. doi: 10.1177/1087057108318331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berry G.T. The role of polyols in the pathophysiology of hypergalactosemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1995;154(7, Suppl 2):S53–S64. doi: 10.1007/BF02143805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slepak T.I., Tang M., Slepak V.Z., Lai K. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in a novel Classic Galactosemia model. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;92:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balakrishnan B., Nicholas C., Siddiqi A., Chen W., Bales E., Feng M., Johnson J., Lai K. Reversal of aberrant PI3K/Akt signaling by Salubrinal in a GalT-deficient mouse model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863:3286–3293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otto G., Herfarth C., Senninger N., Feist G., Post S., Gmelin K. Hepatic transplantation in galactosemia. Transplantation. 1989;47:902–903. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198905000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An D., Frassetto A., Jacquinet E., Eybye M., Milano J., DeAntonis C., Nguyen V., Laureano R., Milton J., Sabnis S. Long-term efficacy and safety of mRNA therapy in two murine models of methylmalonic acidemia. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu X., Yin L., Theisen M., Zhuo J., Siddiqui S., Levy B., Presnyak V., Frassetto A., Milton J., Salerno T. Systemic mRNA Therapy for the Treatment of Fabry Disease: Preclinical Studies in Wild-Type Mice, Fabry Mouse Model, and Wild-Type Non-human Primates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuzyuk T., Viau K., Andrews A., Pasquali M., Longo N. Biochemical changes and clinical outcomes in 34 patients with classic galactosemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41:197–208. doi: 10.1007/s10545-018-0136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richner J.M., Himansu S., Dowd K.A., Butler S.L., Salazar V., Fox J.M., Julander J.G., Tang W.W., Shresta S., Pierson T.C. Modified mRNA Vaccines Protect against Zika Virus Infection. Cell. 2017;169:176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akinc A., Zumbuehl A., Goldberg M., Leshchiner E.S., Busini V., Hossain N., Bacallado S.A., Nguyen D.N., Fuller J., Alvarez R. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leung A.K., Tam Y.Y., Chen S., Hafez I.M., Cullis P.R. Microfluidic Mixing: A General Method for Encapsulating Macromolecules in Lipid Nanoparticle Systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:8698–8706. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b02891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ouattara B., Duplessis M., Girard C.L. Optimization and validation of a reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography method for the measurement of bovine liver methylmalonyl-coenzyme a mutase activity. BMC Biochem. 2013;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J., Yager C., Reynolds R., Palmieri M., Segal S. Erythrocyte galactose 1-phosphate quantified by isotope-dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2002;48:604–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.