Abstract

Previous studies have shown that nucleic acids can nucleate protein aggregation in disease-related proteins, but in other cases, they can act as molecular chaperones that prevent protein aggregation, even under extreme conditions. In this study, we describe the link between these two behaviors through a combination of electron microscopy and aggregation kinetics. We find that two different proteins become soluble under harsh conditions through oligomerization with DNA. These DNA/protein oligomers form “networks,” which increase the speed of oligomerization. The cases of DNA both increasing and preventing protein aggregation are observed to stem from this enhanced oligomerization. This observation raises interesting questions about the role of nucleic acids in aggregate formation in disease states.

Significance

The role nucleic acids play in protein oligomerization is not well understood, even as more biological evidence emerges on the roles RNA/protein granules play in the cell. This study helps to elucidate the important role nucleic acids play in preventing, facilitating, and inducing processes related to protein oligomerization and aggregation.

Introduction

Nucleic acids can be potent molecular chaperones (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). In addition to being required for the folding of proteins in ribonuclear protein complexes (6), nucleic acids in vitro have shown the ability to prevent protein aggregation and aid in protein folding both directly (3, 4, 5) and by transferring clients to ATP-dependent chaperones for refolding (2). However, in what has been referred to as the “Jekyll and Hyde” character of nucleic acids, they can also cause protein aggregation (7). In sharp contrast to the observed chaperone behavior, nucleic acids can stabilize or nucleate protein aggregates linked to disease (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). In vitro, nucleic acids have been shown to induce prion protein conversion into its disease-causing forms (7,10,12,13). Other prion-like proteins’ conversion into disease-causing forms can be nucleated by nucleic acids including fibrillation of α-synuclein (14,15) and superoxide dismutase (6,16) by DNA and the RNA-induced aggregation of Tau (8,9) and p53 (17). In vivo, nucleic acids are commonly found in disease plaques and aggregates in diseased tissue (18,19). In an example of nucleic acids’ seemingly two-faced behavior, they can coalesce into liquid-liquid phase-separated (LLPS) membraneless organelles with proteins (20, 21, 22, 23). Studies have shown that phase separation in the presence of anions may be an important step in the maturation of tauopathies (24). Examples of the LLPS membraneless organelles include cytotoxically induced stress granules (23,25) and the nucleolus (26), the amalgam of DNA/protein dedicated to synthesizing ribosomes. These LLPS membraneless organelles are vital to cellular homeostasis (27); however, aberrant phase separation in the presence of nucleic acids may play a role in aging and disease (28,29). Although it is clear that RNA plays an important role in the formation of stress granules (21,29), how it does so remains less well understood. In an extreme example of the ability of nucleic acids to behave as molecular chaperones, we found that in the presence of bulk DNA, luciferase can be exposed to exceedingly high temperatures (>70°C) and remain soluble in a partially folded state containing some β-sheet character (2). This solubilization far exceeds that typically granted by heat shock proteins (30,31). By performing a combination of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and light scattering kinetics experiments, we find that the DNA prevents or induces aggregation at high temperature by promoting the formation of small oligomers bound to DNA that form “networks.” As DNA can both nucleate and prevent aggregation, this observed behavior represents the proverbial tipping point in the behavior of DNA. This behavior may help elucidate the role nucleic acids play in LLPS organelles or pathogenesis in protein aggregation diseases.

Materials and Methods

Treatment of malate dehydrogenase

L-malate dehydrogenase from pig heart (10127914001; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dialyzed into pH 7.5 40 mM potassium phosphate overnight at 4°C. The protein was then concentrated to ∼300 μM, flash frozen, stored at −80°C, and was used without further purification.

Spin-down assays

For the thermally denaturing spin-down assays, 3.2 μM QuantiLum recombinant luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI) or malate dehydrogenase (MDH) was dissolved in 10 mM (pH 7.5) sodium phosphate buffer, with varying concentrations of the sodium salt of herring testes DNA (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in the same buffer. The samples were then heated for 15 min at 75°C.

For the chemically denaturing spin-down assays, 50 or 100 μM QuantiLum recombinant luciferase was denatured overnight in fresh 4.5 M guanidinium hydrochloride in 40 mM MOPS (pH 7.5) with 25 mM KCl buffer. The denatured luciferase was then diluted to 1 or 2.5 μM from 50 or 100 μM stock, respectively, in 10 mM (pH 7.5) sodium phosphate buffer only or buffer containing varying concentrations of sodium salt of herring testes DNA. Once diluted, the samples were mixed via pipetting and allowed to sit 3 min before centrifugation.

After 15 min of heating or 3 min of incubating on the bench top, 10 μL of each sample was drawn off and kept as the total fraction. Samples were then centrifuged at 16,100 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Immediately after, the supernatant was pipetted off and the pellet redissolved in 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in 1× TG-SDS buffer (Bio Basic, Markham, Ontario, Canada) to the original sample volume. For the sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), a volume equaling 10% of the original solution was kept for electrophoresis of the soluble and pellet fractions.

TEM

For the thermally denatured TEM samples, a spin-down assay was performed with 3.2 μM luciferase or MDH and varying concentrations of DNA the day before TEM was performed. The soluble fraction was stored overnight at 4°C and was used for TEM undiluted. For images containing the pellet of thermally denatured samples, the sample was spun down and resuspended to its original volume immediately before placement on the grids.

For images containing chemically denatured samples, 50 or 100 μM luciferase was denatured overnight the night before imaging in pH 7.5 buffer containing 4.5 M Gu-HCl, 40 mM MOPS, and 25 mM KCl. Before imaging, protein was then diluted to 1 or 2.5 μM from 50 or 100 μM, respectively, in pH 7.5 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer and allowed to aggregate for 3 min before being spun down. For the soluble fraction images, the samples were undiluted before placement on the grid. For the pellet fraction, it was immediately resuspended to the original volume immediately before placement on the grids.

A positive charge was applied to copper mesh grids coated with formvar and carbon (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) using the PELCO easiGlow discharge system. For each sample, 5 μL was applied to a charged grid for 20 s and then gently blotted off with a piece of Whatman filter paper. The grids were rinsed with transfers between two drops of Milli-Q water (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA), blotting between each transfer. Finally, the grids were stained with two drops of a 0.75% uranyl formate or a 2% uranyl acetate solution via a quick rinse with the first drop followed by 20 s of staining in the second drop. After blotting, the grids were allowed to dry for at least 10 min. Samples were imaged on a FEI Tecnai G2 Biotwin TEM (Hillsboro, OR) at 80 kV with an Advanced Microscopy Techniques side-mount digital camera (Woburn, MA).

Steric zipper predictions

Steric zipper predictions were done on the primary sequence of crystal structures of firefly luciferase (Protein Data Bank, PDB: 1LCI) and MDH (PDB: 1MLD). The Rosetta energy scores (32) for six-residue segments were smoothed to increase clarity of high-propensity steric-zipper-forming regions on three-dimensional structures. Smoothing was done by assigning each residue the Rosetta energy from the most favorable segment it was a part of, except prolines that were ignored and colored white. The smoothed scores were mapped onto the PDB structure and colored by Rosetta energy scores as colored in zipperDB.

Light scattering experiments

For aggregation assays, 6.5 μM QuantiLum recombinant luciferase (Promega) was denatured in 4.5 M guanidine-HCl, 40 mM HEPES, 25 mM KCl (pH 7.5) for 15 h at 23°C. The protein was diluted to 65 nM in 40 mM HEPES, 50 mM KCl (pH 7.5) in a solution containing the indicated concentration of DNA, with constant stirring at 20°C. Light scattering at 90° was measured at 360 nm with an F-4500 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), with ∼5 s elapsed to establish a baseline before adding the protein. DNA was purified to a final A260/A280 of 1.8–1.9 via phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation as previously described (2).

CD

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of herring genomic DNA (90 μM on a bp basis) and MDH (3.3 μM on a monomer basis) were measured as a function of temperature both together and separately. The buffer was 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5). The temperature ramped up from 20 to 80°C and back to 20°C at 5°C/min, pausing for CD measurements at every 10°C. CD spectra were measured from 260 to 190 nm. For analysis, the DNA-alone CD spectrum was subtracted from the DNA plus luciferase or MDH spectrum at each temperature and analyzed using BESTSEL (33).

Oligomer area quantification

Micrograph images were imported into Adobe Illustrator (San Jose, CA) and had their height and width measured in pixels using the measure tool and converted to nanometers using the scale bar. If particles were linear, they were measured at their longest point (the height) and their widest point (width) using the measuring tool. The area was determined by treating the particles as an ellipse. If the particles were bent or had branching points, they were sectioned off and treated as separate ellipse segments that were combined for a total area. The areas were then binned and sorted into histograms at the given concentration using KaleidaGraph (Synergy, Reading, PA).

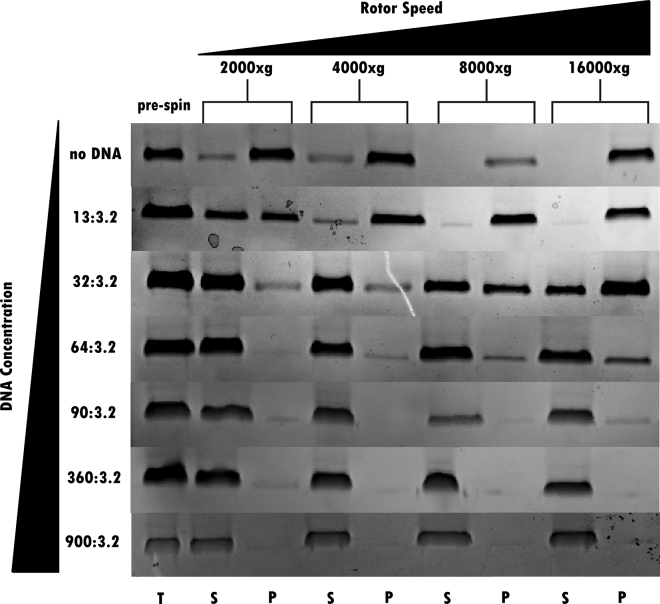

Variable spin-down assay

For thermally denatured samples, a 200 μL sample of 3.2 μM luciferase with varying amounts of DNA was made. Samples were then heated for 15 min at 75°C, and immediately thereafter, 10 μL was drawn off and kept as the total fraction. The remaining 190 μL was divided into 40 μL aliquots and spun at 2000, 4000, 8000, and 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Immediately after centrifugation, the supernatant was pipetted off and the pellet redissolved in 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 1× TG-SDS buffer to the aliquoted sample volume. For the SDS-PAGE, a volume equaling 25% of the aliquoted solution was kept for electrophoresis of the soluble and pellet fractions. As an internal control, the remaining volume of thermally denatured samples was spun down at 2000 × g and treated the same way to assure that samples did not continue to aggregate on the bench top.

For chemically denatured samples, 50 μL of 100 μM luciferase was denatured overnight in fresh 4.5 M guanidinium hydrochloride in 40 mM MOPS (pH 7.5) with 25 mM KCl buffer. The denatured luciferase was then diluted to 2.5 μM in 10 mM (pH 7.5) sodium phosphate buffer containing varying concentrations of DNA to 300 μL. After 5 min of incubation, 10 μL was kept as the total fraction. The remaining 290 μL was divided into 50 μL aliquots and spun at 2000, 4000, 8000, and 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Postcentrifugation, the samples were treated the same as the thermally denaturation samples, except that 20% of the aliquoted solution was kept for electrophoresis of the soluble and pellet fractions.

Proteinase K digest

After soluble and pellet fractions were isolated from the spin-down assay, a portion was digested by proteinase K. Lyophilized proteinase K was purchased from IBI Scientific (Dubuque, Iowa) and resuspended to 10 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris with 10 mM CaCl2 at pH 8.0. For the digestion, proteinase K was diluted to 1 mg/mL in a 50 μL solution containing 40 μL of respective soluble or pellet fraction with 9 μL of pH 83.3 mM HEPES with 25 mM CaCl2 at pH 7.5. Samples were then digested for 30 min at 37°C, and aliquots were kept for both SDS-PAGE and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results

Electron microscopy reveals protein oligomerization on DNA

In our previous study, we found that DNA could grant remarkable solubilization to luciferase (2). Using CD spectroscopy, we found that the complex remained stable not only at high temperature, but that upon returning to room temperature, the complex remained stable and continued to remain stable for at least 2 weeks. To further probe these interactions, TEM was performed to visualize the luciferase-DNA complexes. To create the complexes, DNA and luciferase were incubated together at 75°C for 15 min. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged to isolate the soluble fraction. TEM images of the soluble fraction revealed that the luciferase had formed oligomers and that these oligomers were directly bound by the DNA, which is observable in the images as lines that contact the oligomers (Fig. 1 A). There are many instances of individual oligomers bound separately to the same strand of DNA reminiscent of beads on a string or of protein/DNA networks (Figs. 1 A and S1 A).

Figure 1.

(A and C) TEM images of luciferase oligomers interacting with DNA. (A) Thermal denaturation or (C) chemical denaturation is shown. DNA can be seen bound to several oligomers as silver tendrils. Note that the protein concentration is different in the two different methods of denaturation, but the DNA/protein ratio is the same. (B and D) TEM of luciferase aggregates when no DNA is present. (B) Thermal denaturation or (D) chemical denaturation is shown. Note the difference scale bar size compared to the cases with DNA.

Control micrographs of DNA with no protein verified the lines connecting oligomers are strands of DNA (Fig. S2, A and B). Similarly, visualization of the luciferase pellet with no DNA present showed almost solely the presence of large, somewhat linear aggregates and very few observable small oligomers of comparable size (Fig. 1 B) or homology to the cases with DNA (note the difference in scale between Fig. 1, A and C and Fig. 1, B and D).

In addition to heat denaturation, we performed analogous spin-down experiments in which the luciferase was denatured with guanidine hydrochloride. In these experiments, the protein starts from the unfolded state before being exposed to the DNA under conditions in which it will aggregate. Like the case from heat-denatured protein, the luciferase was solubilized by the presence of DNA (Fig. 3 A), although the solubilization effect is smaller than thermally denatured luciferase.

Figure 3.

(A) SDS-PAGE from spin-down assays with thermally or chemically denatured luciferase in the presence of increasing amounts of DNA are shown. (B and C) A pie chart of the size of luciferase oligomers in TEM images as a function of DNA concentration (DNA/protein ratios shown below each chart) when denatured (B) thermally or (C) chemically is shown. Oligomer sizes are given in nm2. Note, actual concentrations are given in the ratios for the above assays. To see this figure in color, go online.

We then visualized these chemically denatured samples via TEM and observed that similar to heat-denatured luciferase, the chemically denatured luciferase formed oligomers on the DNA (Figs. 1 C and S1 B). Like in the case of heat denaturation, the chemically denatured protein also forms apparent networks of DNA and protein oligomers. In many cases, a single oligomer is observed binding to multiple strands of nucleic acid, and in some cases, a single strand binds multiple oligomers (Figs. 1 C and S1 B). Together, these experiments showed that the solubilization of the protein after chemical or heat denaturation stemmed from protein oligomerization with the DNA.

Two general observations from the TEM micrographs can be made: 1) DNA appears to be forming networks with protein oligomers serving as connections between DNA strands (Figs. 1, A and C and S1, A and B); and 2) in the absence of DNA, there are little to no observable soluble oligomers either in the soluble fraction (Fig. S3, A and B) or in the pellet (Fig. 1, B and D). This is evidence that the two partners are integral to the process of stably forming these oligomers. Given the interwoven nature of the interactions, we would expect a difference between the kinetics of luciferase aggregating on its own and in the presence of DNA.

Light scattering shows DNA/protein oligomerization occurs faster than protein aggregation without DNA

Right-angle light scattering (RALS) experiments monitor the Rayleigh scattering of a particle (or particles) in solution as a function of time. As oligomerization or aggregation occurs, the increased size of the complexes induces light scattering that increases over time.

RALS experiments were performed with chemically denatured luciferase added to a buffer containing varying DNA concentrations. The oligomerization or aggregation was then monitored by light scattering (Fig. 2, A and B). In the absence of DNA (black trace), luciferase aggregated with a half time (t1/2) of ∼35 s. At high DNA concentrations, the oligomerization of DNA plateaued within the dead time of the experiment, indicating a t1/2 of less than about 2 s (Fig. 2 A). This change in the kinetics supports the direct involvement of DNA in the formation of the oligomers, causing an increase in assembly rate.

Figure 2.

Light scattering profile of 65 nM luciferase under chemically denaturing conditions with varying concentrations of DNA. (A) The t1/2 and maximum RALS signal are reduced in the presence of >0.65:0.065 DNA μM base pair/μM protein (purple, green, and cyan traces). Luciferase on its own aggregates at a slower rate (black) is shown. (B) At <0.65:0.065 DNA μM base pair/μM protein, the acceleration is still apparent (blue and red traces), but the maximum RALS signal is increased compared to luciferase (black) on its own.

Interestingly, at low DNA concentrations, the acceleration in oligomerization is still evident, but the maximal light scattering is greater than luciferase by itself (Fig. 2 B). Spin-down assays at these concentrations also showed a preponderance of protein in the pellet, especially in the case of chemical denaturation (Fig. 3 A). This contrasting behavior suggests that in the case in which DNA is limiting, it still speeds oligomerization, but there is a difference either in the size of the oligomers or in their solubility.

Electron microscopy indicates that oligomer size depends on DNA concentration

The RALS experiments suggested that the DNA concentration could have an effect on the size of the oligomers. To explore this possibility, we quantified the size of the DNA/protein complexes observed via TEM. Based on the level of magnification in the TEM images, we estimated the size of the oligomers in terms of their surface area (in nm2) by treating them as an ellipse or combinations of ellipses. In the case of heat denaturation at the lowest concentrations of DNA (13 μM bp DNA:3.2 μM protein), luciferase oligomers spanned two orders of magnitude from 440 to 14,300 nm2 with the median particle size being ∼2000 nm2 (Fig. 3 B). This large spread of particle sizes narrowed with increasing amounts of DNA. At an intermediate DNA concentration of 90 μM bp DNA:3.2 μM protein, the average particle size and range was reduced, shrinking the median to ∼600 nm2 with a range of 320–4100 nm2 (Fig. 3 B). When the DNA ratio was increased to 900 μM bp DNA:3.2 μM protein, the median further decreased to 420 nm2, and the range shrunk to 125–2880 nm2 (Fig. 3 B).

To directly compare with the RALS experiments that used chemically denatured protein, we then performed similar size analysis of the oligomers produced by chemical denaturation and observed a similar trend to the heat denaturation. Like in the heat-denatured case, the size of the oligomers decreased as a function of DNA concentration (Fig. 3 C). The primary difference was that in the chemical denaturation case, the oligomers were somewhat larger than the equivalent concentration in the heat-denatured case (Fig. 3, B and C). These experiments show that the size of the oligomers and the concentration of DNA used in their formation are loosely inversely related.

Similar to the RALS data, it appears the ratios used for the chemically denatured spin-down experiments are nearing a tipping point in the behavior of DNA. At or below 28:1 μM bp DNA:μM protein, the ability to control oligomer size in the soluble fraction is apparently lost. This trend suggests there is enough DNA to maintain a soluble subpopulation but not enough to sufficiently halt oligomerization, leading to the formation of aggregates.

Pellets in low DNA concentrations show morphology similar to soluble oligomers and different than no-DNA pellets

Although the soluble oligomers suggested that DNA concentration affects the size of the oligomers, we looked to the pellet for more clues about how DNA affects the oligomerization or aggregation process. We visualized the pellet from the spin-down assays at low DNA concentrations (Fig. 4, A and B). For these images, the spun-down pellet was resuspended immediately before placing on the grid, similar to luciferase without DNA samples. Surprisingly, regardless of the denaturation method, the aggregates showed homology in shape to the soluble oligomers formed in the presence of high concentrations of DNA and appeared very different than aggregates formed in the absence of DNA. If this was the case, what caused these oligomers to pellet out, whereas the others remained soluble?

Figure 4.

TEM images of luciferase oligomers at low DNA concentrations. Where DNA is evident, it is indicated with black arrows. (A) Thermally denatured luciferase pellet and soluble images are shown. (B) Chemically denatured luciferase pellet and soluble images are shown. Although generally larger, the pellets share similar homology to the soluble fraction oligomers. Note the DNA/protein ratios between denaturation methods are the same.

From the electron microscopy micrographs, we could delineate two differences between the soluble and insoluble oligomers. First, the oligomers were larger in the pellets (Table 1). These insoluble oligomers decreased in size with increased DNA concentration, suggesting that size is one factor that led these oligomers to precipitate. It appears that oligomers with an area greater than ∼2000 nm2 were likely to pellet out.

Table 1.

Median Oligomer/Aggregate Sizes in nm2 at Low DNA Concentration

| Heat |

Chemical |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM DNA | Soluble | Pellet | μM DNA | Soluble | Pellet |

| 0 | N/A | 24,700 | 0 | N/A | 129,000 |

| 13 | 1970 | 9640 | 10 | N/A | N/A |

| 32 | 1330 | 5350 | 25 | 2690 | 36,400 |

| 64 | 1150 | 1840 | 50 | 2360 | 12,100 |

Luciferase concentrations are 3.2 and 2.5 μM for heat and chemical denaturation experiments, respectively.

Second, although DNA was readily apparent in the soluble oligomer networks in both chemical and thermal soluble fractions, especially at higher DNA concentrations, little to no exposed DNA was visible in the pellets, despite similar morphology to the oligomers in the soluble fraction (Fig. 4, A and B). Because of the low DNA concentrations, it is likely that any DNA in these oligomers is entirely bound by the protein, leaving little exposed and visible.

To check whether the pellet fractions contained DNA, we digested the soluble and pellet fractions with proteinase K for 30 min and looked for the presence of DNA via agarose gel (Fig. S4, A and C). At higher DNA concentrations, more of the DNA remained soluble, whereas at lower concentrations, a larger portion of the DNA could be found in the pellet. This observation confirms that even though the DNA is less visible in the pellet TEM images, it is still present but no longer exposed. This solvent accessibility of DNA could also in part explain the change in solubility, as attached and exposed DNA could work in a similar fashion to a solubility tag through its exposed surface charge.

Variable spin-down assays indicates that oligomer size and solubility depend on DNA concentration

As an alternative qualitative assessment of how DNA affects the size and solubility of these particles, variable spin-down assays were performed. Over the course of these experiments, chemically or thermally denatured luciferase was incubated with varying amounts of DNA and spun down at increasing rotor speeds. As previously observed, for both chemical and thermal denaturation methods, high rotor speeds pelleted the protein in both the no DNA and low DNA cases, although protein with higher DNA concentrations never pelleted (Fig. 5). With no DNA, the protein pelleted at even the lowest spin speed. However, with even a small amount of DNA present, the protein required significantly higher spin speeds to pellet at a level similar to the no-DNA case (Fig. 5). This observation is consistent with the observed increase in RALS signal with low DNA concentrations, as there is no pelleting force in a RALS experiment, and the less soluble and larger oligomers would remain suspended. Similar trends arise with chemically denatured sample, although higher DNA concentrations are required to maintain solubility at increasing rotor speeds (Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

SDS-PAGE results of variable spin-down assay from thermal aggregation. From left to right, the rotor speed is increasing, and from top to bottom, there is increasing DNA concentration. The oligomers remain soluble at greater rotor speeds with increasing amounts of DNA.

One important question is whether this extreme solubilization and oligomer formation with DNA is specific to luciferase, or do other proteins also exhibit this behavior? With these questions in mind, we turned to MDH to analyze whether it displayed similar behavior.

MDH also oligomerizes on DNA, displaying generality

Like many other proteins often used for measuring chaperone activity, MDH aggregates as a function of temperature (34). We subjected MDH to the same extreme heat denaturation test as luciferase and monitored the aggregation via spin-down assays in the presence of varying concentrations of DNA. Similar to luciferase, the MDH completely aggregated in the absence of DNA, but the DNA effectively solubilized the MDH at high temperature (Fig. 6 A).

Figure 6.

TEM, CD, and SDS-PAGE of MDH-DNA complexes. (A) SDS-PAGE of MDH at the given condition is shown. (B) CD of 3.2 μM MDH with 90 μM bp DNA at several temperatures are shown. “For” indicates the forward melting experiment up to 80°C, and “Rev” indicates the reverse experiment back to room temperature. (C) Micrographs of 3.2 μM MDH and 360 μM bp DNA are shown. Zoomed out micrographs shown in Fig. S6. (D) A TEM micrograph of MDH aggregate in the absence of DNA is shown. Note the change in scale bar size. P, pellet fraction; S, soluble fraction; T, total fraction. To see this figure in color, go online.

To test whether the MDH retained partial structure in the presence of DNA at high temperature like luciferase, we measured its CD spectrum under the same conditions (Fig. 6 B). The trends in the CD spectra of MDH were again similar to those observed with luciferase. In the absence of DNA, all CD signal was lost because of protein aggregation in the cuvette. In contrast, in the presence of DNA, some secondary structure (primarily β-sheet in nature) was observable at high temperature (Fig. 6 B, blue trace) and remained upon return to room temperature (Fig. 6 B, orange trace). These experiments showed that like luciferase, MDH is held in a partially folded state by the DNA at high temperature and does not aggregate. These data also indicate that the extreme protein solubilization conferred by DNA is at least somewhat general.

Finally, TEM images of the MDH/DNA complexes also demonstrated that the MDH forms oligomers on the DNA (Figs. 4 C and S6). These data indicate that like in the case of luciferase, the DNA confers the extreme solubilization through protein oligomerization. Also similar to luciferase, the TEM images show many instances of multiple DNA-bound oligomers (Fig. 6 C). In the absence of DNA, MDH forms large aggregates (Fig. 6 D), along with some small oligomers (Fig. S3 C) that are below the detection limit of the spin-down assays (Fig. 6 A). In total, these observations indicate that the oligomer formation by luciferase and DNA is not specific to just luciferase and could be a more general protein property.

Discussion

Using a combination of TEM and RALS kinetics experiments, we discovered that the extreme solubilization conferred onto luciferase and MDH by high concentrations of DNA arises from its promotion of oligomerization. The size of the oligomers is dictated by the concentration of DNA, with chemical denaturation producing somewhat larger oligomers than those produced by heat denaturation. These larger particle sizes would be expected because of the increased speed of aggregation from chemically denatured states compared to the slower heat-induced aggregation. Under these conditions, the protein/DNA complexes are apparently stable enough to prevent the protein from dissociating from the DNA to form aggregates. These oligomers have distinct morphology from aggregates formed in the absence of DNA.

Continuing the trend, at low concentrations of DNA, the oligomers increase in size until they become insoluble. These insoluble oligomers maintain similar morphology to the soluble oligomers. Although DNA cannot be seen via TEM in this case, it is present in the pellet fraction, suggesting that a lack of exposed DNA also likely limits the solubility of these oligomers formed with limiting concentrations of DNA.

This oligomerization process occurs faster than the protein aggregation on its own. This observation suggests that the complexes formed by DNA-facilitated oligomerization are kinetically stable compared to the case of protein aggregation that does not involve DNA. Of note, the increased speed of oligomerization occurred at both high DNA concentration in which oligomers were small, as well as at low concentration in which the oligomers were large. In the high DNA concentration case, the only opportunity for increased oligomerization speed would be either in the protein’s monomer or very small oligomer form. This increase in speed is likely due to increased local protein concentration in the DNA/oligomer networks by binding either misfolded monomer and/or small luciferase oligomers.

Interestingly, under chemical denaturation conditions, the images suggest that the luciferase oligomers are encapsulated by DNA (Figs. 1 B and S1 B). This encapsulation of the oligomers could in part explain the ability of DNA to control the size of the oligomers. At higher DNA concentrations, DNA surrounds the protein(s). Encapsulating the oligomers could discourage new monomers from entering because of the accumulated negative charge while at the same time restricting any proteins within the net of DNA from leaving, leading to higher local protein concentrations and enhancing oligomerization.

The mechanism of the DNA/protein oligomer interactions appears to not be due to simple bulk electrostatics. MDH has a pI of 8.6 and luciferase a pI of 6.4. Under the conditions used here, the proteins would be positively and slightly negatively charged, respectively. It is possible only local patches of positive charge are required for the interaction.

To gain structural insight into the oligomerization behavior of the proteins, a sequence-structure dependent search of luciferase and MDH for steric zippers was performed (Fig. S7). These aggregation-prone regions have been shown to promote fibril-like structures as well as oligomerization, which may explain some of the behavior observed here (32). We found that there are multiple stretches prone to steric zipper formation that could be contributing to the β-sheet-like nature of the oligomers seen in MDH and luciferase (2). Intriguingly, in MDH and luciferase, these steric zipper sequences are often surface exposed or near to the surface and therefore would not require complete unfolding of the protein to be accessible for oligomer formation (Fig. S7, black arrows).

The observation of DNA/oligomer networks suggests interesting ideas on how nucleic acids could facilitate the formation of stress granules and other liquid-liquid separated states. Notably, the oligomers observed here can remain soluble by maintaining contact with sufficient DNA. It is possible that a similar process contributes to the formation of bodies such as stress granules. In times of stress, including high temperature, these stress granules keep high concentrations of aggregation-prone proteins in a liquid state, perhaps through their interaction with the highly soluble RNA (29,35). Recent studies have suggested that nucleic acids form the primary scaffolding used by stress granules (21,36), and that the nucleolus, which has very high nucleic acid content, serves as a holding place for misfolded proteins (37).

We have shown here that under conditions in which proteins are unfolding because of stress, partially folded oligomers of proteins bind nucleic acids and could serve as vertices in a nucleic acid scaffold. Although in this work we tested a wide range of protein/nucleic acid ratios, concentrations of both nucleic acids and protein are considerably higher in the cell and in its subcompartments than those used here (38,39). To our knowledge, the exposed nucleic acid/protein ratio in relevant subcompartments, either under normal or stress conditions, is not clear, but the work described here suggests that in these crowded environments, the shift from extreme solubilization to aggregation could be stark and made more severe through nucleic acids’ interactions with unfolded or partially folded proteins.

A very recent study has found that similar protein oligomerization effects can be achieved with polyphosphate (40). It is therefore possible that some of the behavior observed here is general to molecules with a phosphate backbone. Previous investigation has shown that the base composition of DNA affects protein aggregation kinetics (2), suggesting that the detailed mechanisms can be different between DNA and polyphosphate but that some of the general properties may be conserved.

In this work, we view the precipice of nucleic acids’ effect on protein folding and aggregation. In this case, the acceleration of oligomerization can prevent the aggregation of proteins even under extreme conditions, but when DNA becomes limiting, it accelerates aggregation. This counterintuitive observation highlights the complicated roles that nucleic acids can play in both the biology and pathology of protein aggregation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Bardwell, U. Jakob, N. Wingreen, P. Ronceray, and D. Eisenberg for insightful conversations on the article.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R00 GM120388 and National Science Foundation grant MCB 1616265.

Editor: Markus Buehler.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.11.022.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Horowitz S., Bardwell J.C. RNAs as chaperones. RNA Biol. 2016;13:1228–1231. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1247147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Docter B.E., Horowitz S., Bardwell J.C. Do nucleic acids moonlight as molecular chaperones? Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4835–4845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi S.I., Lim K.H., Seong B.L. Chaperoning roles of macromolecules interacting with proteins in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:1979–1990. doi: 10.3390/ijms12031979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi S.I., Han K.S., Seong B.L. Protein solubility and folding enhancement by interaction with RNA. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay S., Das B., Dasgupta C. Reactivation of denatured proteins by 23S ribosomal RNA: role of domain V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8284–8287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin J., Hu S., Liu C. DNA-triggered aggregation of copper, zinc superoxide dismutase in the presence of ascorbate. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva J.L., Cordeiro Y. The “Jekyll and Hyde” actions of nucleic acids on the prion-like aggregation of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:15482–15490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.733428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinkel P.D., Holden M.R., Margittai M. RNA binds to tau fibrils and sustains template-assisted growth. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4731–4740. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kampers T., Friedhoff P., Mandelkow E. RNA stimulates aggregation of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments. FEBS Lett. 1996;399:344–349. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordeiro Y., Machado F., Silva J.L. DNA converts cellular prion protein into the β-sheet conformation and inhibits prion peptide aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:49400–49409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin J., Chen R., Liu C. Nucleic acid induced protein aggregation and its role in biology and pathology. Front. Biosci. 2009;14:5084–5106. doi: 10.2741/3588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C., Zhang Y. Nucleic acid-mediated protein aggregation and assembly. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2011;84:1–40. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386483-3.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasan S., Mong P.Y., Grossman A. Interaction of prion protein with small highly structured RNAs: detection and characterization of PrP-oligomers. Neurochem. Res. 2006;31:629–637. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegde M.L., Rao K.S. DNA induces folding in alpha-synuclein: understanding the mechanism using chaperone property of osmolytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;464:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munishkina L.A., Fink A.L., Uversky V.N. Accelerated fibrillation of alpha-synuclein induced by the combined action of macromolecular crowding and factors inducing partial folding. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:252–260. doi: 10.2174/156720509788486491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W., Han Y., Liu C. DNA is a template for accelerating the aggregation of copper, zinc superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5911–5923. doi: 10.1021/bi062234m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovachev P.S., Banerjee D., Sanyal S. Distinct modulatory role of RNA in the aggregation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 core domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:9345–9357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.762096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginsberg S.D., Galvin J.E., Trojanowski J.Q. RNA sequestration to pathological lesions of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 1998;96:487–494. doi: 10.1007/s004010050923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginsberg S.D., Crino P.B., Trojanowski J.Q. Sequestration of RNA in Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques. Ann. Neurol. 1997;41:200–209. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Protter D.S.W., Parker R. Principles and properties of stress granules. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bounedjah O., Desforges B., Pastré D. Free mRNA in excess upon polysome dissociation is a scaffold for protein multimerization to form stress granules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:8678–8691. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitrea D.M., Kriwacki R.W. Phase separation in biology; functional organization of a higher order. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panas M.D., Ivanov P., Anderson P. Mechanistic insights into mammalian stress granule dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:313–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201609081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wegmann S., Eftekharzadeh B., Hyman B.T. Tau protein liquid-liquid phase separation can initiate tau aggregation. EMBO J. 2018;37:e98049. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray M.J., Jakob U. Oxidative stress protection by polyphosphate--new roles for an old player. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015;24:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Audas T.E., Jacob M.D., Lee S. Immobilization of proteins in the nucleolus by ribosomal intergenic spacer noncoding RNA. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franzmann T.M., Jahnel M., Alberti S. Phase separation of a yeast prion protein promotes cellular fitness. Science. 2018;359 doi: 10.1126/science.aao5654. eaao5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alberti S., Hyman A.A. Are aberrant phase transitions a driver of cellular aging? BioEssays. 2016;38:959–968. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mateju D., Franzmann T.M., Alberti S. An aberrant phase transition of stress granules triggered by misfolded protein and prevented by chaperone function. EMBO J. 2017;36:1669–1687. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogk A., Tomoyasu T., Bukau B. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 1999;18:6934–6949. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakob U., Gaestel M., Buchner J. Small heat shock proteins are molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1517–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldschmidt L., Teng P.K., Eisenberg D. Identifying the amylome, proteins capable of forming amyloid-like fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:3487–3492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915166107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Micsonai A., Wien F., Kardos J. Accurate secondary structure prediction and fold recognition for circular dichroism spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E3095–E3103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500851112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartman D.J., Surin B.P., Høj P.B. Substoichiometric amounts of the molecular chaperones GroEL and GroES prevent thermal denaturation and aggregation of mammalian mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:2276–2280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maharana S., Wang J., Alberti S. RNA buffers the phase separation behavior of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Science. 2018;360:918–921. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moon S.L., Morisaki T., Stasevich T.J. Multicolour single-molecule tracking of mRNA interactions with RNP granules. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:162–168. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frottin F., Schueder F., Hipp M.S. The nucleolus functions as a phase-separated protein quality control compartment. Science. 2019;365:342–347. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw9157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheung M.C., LaCroix R., Ehrlich D.J. Intracellular protein and nucleic acid measured in eight cell types using deep-ultraviolet mass mapping. Cytometry A. 2013;83:540–551. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung M.C., Evans J.G., Ehrlich D.J. Deep ultraviolet mapping of intracellular protein and nucleic acid in femtograms per pixel. Cytometry A. 2011;79:920–932. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoo N.G., Dogra S., Jakob U. Polyphosphate stabilizes protein unfolding intermediates as soluble amyloid-like oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:4195–4208. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.