Abstract

The cashew tree or Anacardium occidentale, a tropical tree native from Brazil, was introduced to Asia and Africa by European explorers in the sixteenth century. The world production of cashew nuts reached 4.89 million tons in 2016, with Vietnam being the largest producer of nuts. The cashew market is expected to remain strong due to high production growth in some areas, such as West Africa. Cashew production is potentially an important value for small farmers in emerging countries and there is an immense potential for cashew by-product exploitation that can add value to cashew agribusiness. The present work carries out a technological prospection in databases of patents and scientific papers mapping the applications of cashew nuts and cashew apple. It was possible to identify 2376 patent applications and 586 scientific publications on cashew nuts and cashew apple together. After the analysis of patents and scientific papers, it was possible to note that the cashew tree is a tree of multiple uses that can contribute in several industry sectors. Thus, the present study mapped the potentiality of applications of the various parts of the cashew, which allows adding value to the cashew agribusiness.

Keywords: Anacardium occidentale, Cashew agribusiness, Technological monitoring, Cashew nut, Cashew apple

Introduction

The cashew tree or Anacardium occidentale belongs to the Anacardiaceae family, characterized by tropical and subtropical trees and shrubs that have branches always provided with channels that produce resin and altered leaves. There are more than sixty genera and four hundred species related to the genus Anacardium, which produce similar and also edible fruits, all of natural occurrence in Brazil (Moreira 2002; Brizicky 1962; Khosla et al. 1973; Mitchell and Mori 1987). The word “Anacardium” is of Greek origin and means “inverted heart” (aná: over; cárdia: heart) in allusion to the fruit shape (Mothé et al. 2006).

Cashew trees have many diverse characteristics. They can vary from large, Amazonian trees, reaching up to 40 m in height and presenting fleshy pseudofruit or cashew apple that is little developed (Anacardium giganteum), to arboreal forms of medium size, not exceeding 4 m in height (Anacardium othonianum), and trees which are no taller than 80 cm (Anacardium humile) (Abdul and Peter 2010). In these latter cases, the chestnut presents the same characteristics and uses of the common cashew tree (A. occidentale L.), only the pseudofruit or cashew apple presents different size and acidity (Tassara 1996). The common cashew belongs to the species A. occidentale L. This denomination was given by Lineu and it was included in the Anacardiaceae family, genus Anacardium and species occidentale Linn) being the only one cultivated on a commercial scale in the world and the most important of all species of the genus (Medina et al. 1978; Moreira 2002).

The common cashew tree totally loses its leaves during the year, adapted to the growth in full sun, with clear preference for sandy and well drained soils, that is, it is a perennial plant. The first flowering takes place between the 3rd and 5th year of life. The production is stabilized in the 8th year of the plant, which lives on average 35 years. Flowers are abundant during the months of June until September and fruiting is from November, and can extend until the month of January (Lorenzi 2004). The cashew tree is a halophile (which is salt-loving), and is well adapted to the humid and dry tropical climate. The plant requires heat for its development, being very sensitive to the cold and frost. The average annual temperature should be around 27 °C, with limits between 22 and 32 °C. Low temperatures adversely affect the flowering and fruiting of the cashew tree, which is known for its drought tolerance (Lim 2012). Despite the rusticity of the cashew, its orchard does not dispense with the use of fertilizers and other inputs to be competitive. The trees have a large canopy, always covered with leaves, which, consequently, serve to produce shade (Pimentel et al. 1998; Freire et al. 2002). The greatest profits in cashew production are obtained when the planting is done with grafted seedlings of clones of the precocious dwarf cashew tree. This cashew tree is named after its small size and precocity (Embrapa 1993).

Contrary to what most people think, the true fruit of the cashew nut is the chestnut, which consists of an almond wrapped in a hard shell, while the peduncle (pseudofruit) or cashew apple develops in the form of a juicy, carbohydrate-rich material known as the cashew pulp (Mothé et al. 2006; Mothé and de Freitas 2018). However, not only as food can the cashew be harnessed. In this review the potentiality of applications of cashew nuts and cashew apple will be explored through a technological prospection in scientific papers and patents.

Cashew agribusiness

Cashew agribusiness exploration models present diversities around the world. The cashew can be found from spontaneous or semi spontaneous forests to systematized crops, in small or large areas. In general, as well as specifically in Brazil, small areas of crops, generally in consortium with other cultures of local interest, prevail. It is worth mentioning that cashew exploration in monocultures presents itself as a main difficulty in Brazil, hence the increase of complications of phytosanitary order (Lorenzi 2004).

The cashew agroindustry has a well-defined productive geographical occupation, concentrating on few Third World countries, such as India, Brazil and a few others from East Africa (Lorenzi 2004). The main business of cashew is in the marketing of the almond, in view of the global exports that are destined, notably, to the United States, Europe, and some Asian countries. It is an important socio-economic activity by the large number of people involved in agricultural production and industrial processing in poor regions of the world, and by the revenue generated for the producing countries (Melo 2002).

Because its production focuses on countries considered underdeveloped or developing, the cashew is considered a product of great socio-economic importance in the world. According to data from National Supply Company (CONAB), Brazil produced about 102,000 tons of cashew nuts in 2015, of which 12,957 tons were exported, mainly to the Netherlands, Canada and the United States (Conab 2018).

According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Brazil was the 14th largest producer of cashew nuts in 2016, with a production of 75,500 tons. Vietnam, Nigeria, India and Côte d’Ivoire were the largest producers with productions of 1,221,070; 958,860; 671,000 and 607,300 tons respectively FAO (2018).

Data from Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics showed that in Brazil in 2017 the planted area of cashew trees was 564,456 ha: the area harvested of cashew nuts was 535,547 ha IBGE (2018). Although the quantity of cashew nuts exported has decreased, probably due to the fall in production, prices have been increasing to reach 9987 US$/kg in 2017, an increase of 20.2% over 2016. According to data from (MDIC 2018), the cashew nut was 158th in the ranking of the main products exported in 2017. A few destinations of Brazilian exports of cashew nuts include the United States (47%), Canada (9.7%), the Netherlands (8.6%), Argentina (7.3%) and others.

Scientific and technological monitoring

The cashew is a multipurpose plant, both food and medicinal. In order to have an overview of the technological and scientific development related to the application of the cashew, a technological survey was carried out in the database of patents and papers on the parts of the cashew exports: cashew nuts and cashew apple.

Initially, a preliminary study was conducted to choose the patent database. Some search bases for internationally recognized patents were chosen, such as: Espacenet, USPTO, Patent Scope, Derwent and INPI. In order to broaden the scope of the preliminary study, each general search term was selected for each part of the cashew tree. The data were collected between 1963 and 2018 and covered the entire period available in the respective databases searched.

A prospect was also carried out in scientific studies, through the web of science database. At this stage, we sought to recover the maximum number of scientific and patent documents and to determine a panorama of the existing technologies in Brazil and in the world. The search strategy adopted at this stage related the same terms used in patents search. The data collection was carried out in October/2018 and covered the period from 1945 to 2018.

From the data collection carried out during the preliminary study, in the several patent databases surveyed it was shown that the Derwent database was more embracing when compared with the other free databases. The search using the Derwent database retrieved 2376 patents, followed by the Espacenet, Patent Scope, USPTO, and INPI databases with 1621, 1177, 33 and 77 patent application repositories, respectively. Because it was more comprehensive, the Derwent database was chosen to carry out the patent analysis. The database of scientific papers (web of science) retrieved 586 scientific publications.

In the following sections, the graphs of this technological monitoring are presented as well as the applications found in the databases of patents and scientific papers on cashew nuts and cashew apple.

Cashew nut

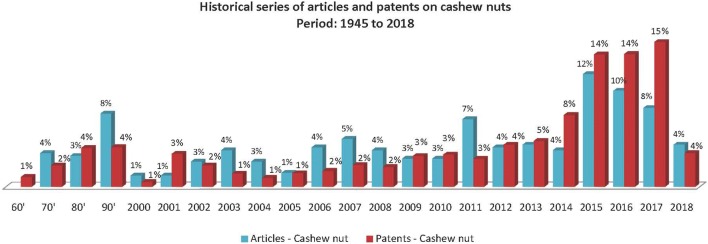

Figure 1 presents the historical series of papers and patents on cashew nuts. It is possible to note that the number of patents is well above the number of papers. The first patents found on cashew nuts are from the 60’s and the years 2015, 2016 and 2017 were the years that most patents on cashew nuts were filed and also the year when papers were most published, probably due to the increase in the cashew crop that occurred in the year 2015 in Brazil that stimulated research on this topic and the growing concern of the population in recent years to eat foods with a high nutritional index.

Fig. 1.

Historical series of papers and patents on cashew nuts.

Source: Adapted from web of science and Derwent, 2018

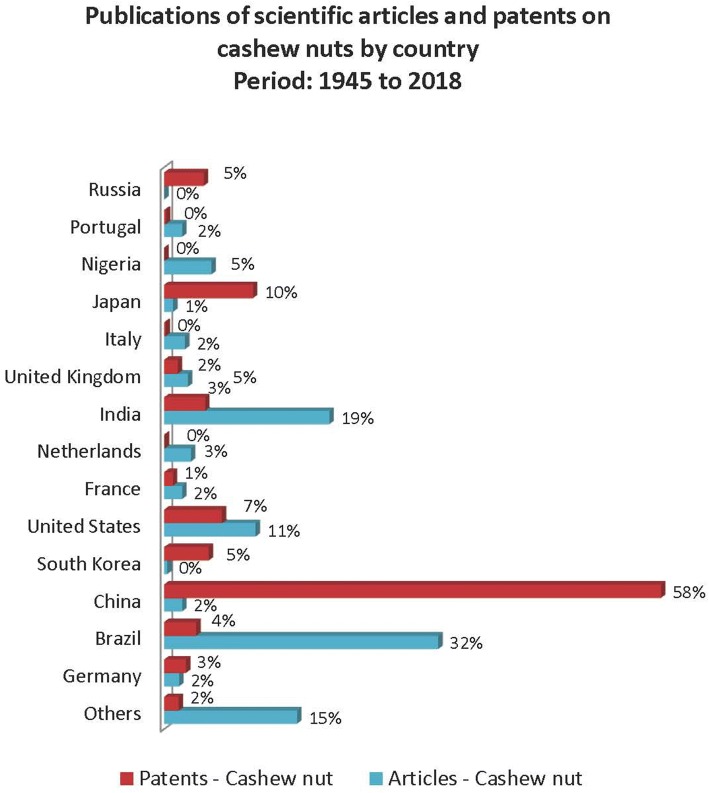

Figure 2 shows the publications panorama of scientific papers and patents by country. China was the country that most deposited patents on cashew nuts (1184). However, they have few scientific publications, only 6. Brazil and India are the countries that have the most scientific publications, with 93 and 56 respectively; however, they deposited few patents, only 76 and 32 respectively.

Fig. 2.

Publications of scientific papers and patents on cashew nuts by country.

Source: Adapted from web of science and Derwent, 2018

Figure 3 shows the publications of scientific papers and patents of cashew nuts by area of knowledge. The vast majority of scientific publications (240) and patents (1232) on cashew nuts were in Food science and Technology. The other areas of knowledge were Chemistry, with 579 of patents and 10 of papers, Engineering, with 507 of patents and 10 of papers and Agriculture, with 80 of scientific papers.

Fig. 3.

Publications of scientific papers and patents on cashew nut by area of knowledge.

Source: Adapted from web of science and Derwent, 2018

Regarding the scientific and technological monitoring carried out, it was possible to construct a block diagram with the main applications of cashew nuts that are shown in the Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Block diagram of products obtained from cashew nuts.

Source: Elaboration based on web of science

The cashew nut is the true fruit of the cashew tree, presenting three distinct parts: the bark, the almond and the film (Mothé et al. 2006; Carestiato et al. 2009; Mothé et al. 2017). The bark, which accounts for 65–70% of the weight of the chestnut, consists of a leathery epicarp, crossed by a spongy mesocarp, whose alveoli are filled by a caustic and inflammable liquid—the CNSL (cashew nut shell liquid). The film, or almond tegument, which represents about 3% of the weight of the nut, is rich in tannin. The almond, which is the edible part of the chestnut, made up of two ivory cotyledons, accounts for about 28–30% of its weight, but in the industrial process the average yield is only 21% (Paiva et al. 2000).

The edible part of the chestnut is the almond that should only be consumed toasted due to the presence of acids that burn the mouth. In addition to its pleasant taste, the widespread consumption of cashew nuts is due to its nutritional properties. Such properties are closely linked to the high lipid content, which is predominantly given by monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and has been shown to decrease levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and coronary heart disease (Hu et al. 2001).

It is possible to observe that the applications found for cashew nuts in technological monitoring refer mainly to food compositions. This is because the cashew nut has a high nutritional value and is considered a source of high quality protein, rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids and highly energetic, rich in fats and carbohydrates, with high levels of calcium, iron and phosphorus (Aremu et al. 2006).

Cashew nut is rich in high quality oils (40–47%), among which are: oleic acid (73.7%), linoleic acid (14.3%), palmitic acid (7.5%) and stearic acid (4.5%), as well as traces of arachidic and linolenic acid (Mothé et al. 2006). The carbohydrate content was 1.4% (Akinhanmi et al. 2008) to 26.8% (Aremu et al. 2006), with 20–25% being the most common values, depending on the level of fat and crude protein, in turn determined by cashew variety and environmental conditions (Akinhanmi et al. 2008).

The protein in this nut content varies considerably, from 19% (Venkatachalam and Sathe 2006) to 36% (Aremu et al. 2006). An amino acid profile analysis was performed by Venkatachalam and Sathe (2006) using analytical methods and it was shown that the highest amounts are: glutamic acid (22.4–13.6%), aspartic acid (5.6–10.2%) and leucine (6.2–8.0%). The high quality of the amino acid supply of cashew nuts is further confirmed by the high value of the essential amino acids, representing up to 47% (Aremu et al. 2007).

Regarding mineral composition, studies showed high potassium content (up to 38%), followed by magnesium and calcium (Aremu et al. 2006). It has been found that the calcium content is similar to phosphorus, indicating that cashew nuts are a good source of minerals for bone formation. Zinc and iron were the least abundant components (Akinhanmi et al. 2008).

Relevant healthy benefits were attributed to cashew nuts by different authors:

Cancer prevention Proanthocyanidins are a class of flavonoids that fight tumor cells, preventing them from dividing further. These proanthocyanidins and the high copper content in cashew nuts help fight cancer cells that help prevent colon cancer (Patil 2017);

Cardiovascular protection Cashew nuts are low in fat when compared to other nuts with monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which lower levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and coronary heart disease (Hu et al. 2001). Cashew nuts also have the property of lowering blood pressure with the help of the magnesium present in them;

Nerve protection Magnesium, present in cashew nuts, is stored on the surface of bones, preventing calcium from entering nerve cells thus maintaining blood vessels and relaxed muscles (Patil 2017);

Antioxidant action Selenium, copper and magnesium present in cashew nuts act as cofactors for many enzymes, acting as anti oxidant elements (Aremu et al. 2007);

Vitamin source Cashew nuts are rich in vitamins such as riboflavin, pantothenic acid, thiamine, niacin etc. These vitamins protect the body against sideroblastic anemia and pellagra (Akinhanmi et al. 2008).

Cashew processing methods have evolved over the years, with the introduction of automation at some levels of the processing chain, as well as the diversification of operations among countries to meet environmental conditions and production capacity. The processing of cashew nuts, which involves the removal of almond from the bark, remains largely restricted to three large countries: India, Vietnam and Brazil (Dendena and Corsi 2014).

In general, cashew processing has developed as a low-investment activity with minimal use of technology. It was based on low-cost labor (in relation to the value of the product). The profitability of cashew processing depends, to a large extent, on the proportion of grains extracted without being broken or damaged. For many years, the technology failed to provide a commercially viable solution to this problem (Fitzpatrick 2011).

The Brazilian industry developed in a different course, with few large mechanized factories. Brazilian processing is characterized by high operating costs, with investment levels and salary levels much higher than in other cashew-producing countries (Paiva et al. 2000).

In African countries, cashew processing remains a small-scale activity. African factories tend to adopt new technology faster than their competitors in India. This was mainly driven by problems associated with workforce management, rather than any noticeable improvement in the performance achieved by the processing equipment (Fitzpatrick 2011).

The objective in the processing of cashew nuts is to remove the highest possible weight of cashew nuts in the bark, uninterrupted and with the characteristic light brown color of the cashew. It is a food product, therefore, the taste should remain as natural as possible and the process must be done safely. There are several different methods of peeling. This process has traditionally been done manually, which is still the case for small-scale processing companies, whereas in large-scale processing facilities it has been converted into mechanized operations (Dendena and Corsi 2014).

Cashew apple

Curiosily, the real fruit of the cashew nut is the actual nut, which consists of an almond wrapped in a hard shell, while the peduncle (cashew apple or pseudofruit) develops in the form of a juicy, rich carbohydrate material known as the cashew pulp (Mothé et al. 2006).

Figure 5 presents the historical series of papers and patents on cashew apple. The first patent registrations on cashew apple are from 1975. The years in which there were the highest number of patents were 2011, 2012 and 2014 with 8, 5 and 5 respectively. It is observed that the first publication on the cashew apple dates from 1963, with 2015 being the year that there were more publications. This fact is probably due to the increase in the cashew crop that occurred in the year 2015 that led to research on this topic.

Fig. 5.

Historical series of papers and patents on cashew apple.

Source: Adapted from web of science and Derwent, 2018

Figure 6 shows the publications on cashew apple by country. The country that made the most scientific publications (148) was Brazil, followed by India (29) and Nigeria (14). Regarding to patents, the countries with the largest quantity of patents were Brazil and India, both with 5 patents each. Second was the Philippines with 4 patents. This portrays the potential interest of Brazilian and Indian researchers in innovative studies on cashew apple.

Fig. 6.

Publications of scientific papers and patents on cashew apple by country.

Source: Adapted from web of science and Derwent, 2018

In Fig. 7, the scientific publications and patents on cashew apple are classified by area of knowledge. Most of the papers on cashew apple are in the area of Food Technology and Science with 103 of papers followed by Agriculture, Engineering, Chemistry, Biotechnology and Pharmacy/Medicine with 62, 29, 18, 15 and 12 respectively. Regarding patents, the majority of patent deposits on cashew apple were in the area of Food Science and Technology, with 25 followed by Biotechnology and Engineering with 7 and 5 respectively.

Fig. 7.

Publications of scientific papers and patents on cashew apple by area of knowledge.

Source: Adapted from web of science and Derwent, 2018

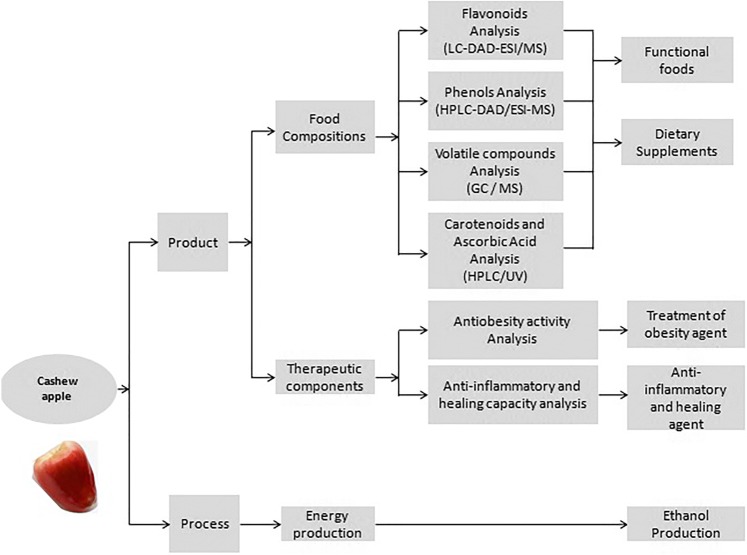

As the scientific and technological monitoring was performed, it was possible to construct the block diagram with the applications for cashew apple shown in the Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Block diagram of products obtained from cashew apple.

Source: Elaboration based on web of science

It is possible to observe that cashew apple has several and important uses and applications. Its consumption as processed is much more widespread than as a raw fruit, because it is highly perishable. Its use is mainly due to the high content of vitamin C, since the juice is five times richer than other citrus fruits and four times richer than sweet orange (203.5 mg/100 ml of juice versus 33.7 and 54.7, respectively) (Akinwale 2000). In addition, this apple contains a considerable level of minerals, mainly calcium and phosphorus. It also contains small proportions of tannins (up to 0.35%) that confer an astringent fruit flavor (Nair 2010). Such limitation is overcome by mixing cashew apple juice with others, such as mango, orange and pineapple, which also serve to increase the vitamin C content (Akinwale 2000) or by processing the fruit.

Some popular products obtained from cashew are cashew apple vinegar, jam, chutney, pickles and a wide variety of soft drinks. Cashew apple juice is also fermented to produce liqueur in India, known as feni, with 40% v/v alcohol content.

Cashew apple remaining residues after juice extraction are nutritious because they contain around 9% of protein, 4% of fat, 8% of crude fiber and almost 10% of pectin. Its use in making various products, such as jams, jellies and beverages, is widespread, as is the feeding of cattle after drying (Nair 2010).

It was also found publications on the analysis of flavonoids, phenols, volatile compounds, antioxidants, carotenoids and ascorbic acid, aiming at the use of cashew apple as a functional food in formulations and dietary supplements.

Brito et al. (2007) investigated the presence of flavonoids in cashew apple. Liquid chromatography, with diode arrangement detection and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC–DAD–ESI/MS), was used to identify and quantify flavonoids in cashew apple. One anthocyanin and thirteen glycosylated flavonols were detected in a methanol–water extract. Another study that has also analyzed the presence of flavonoids in tropical fruits of Brazil was performed using HPLC by Hoffmann-Ribani et al. (2009). Cashew apple showed to be an consistent source of flavonoids.

Michodjehoun-Mestres et al. (2009) extracted with acetone the bark and meat of four cashew apples genotypes from Brazil and Benin (West Africa), purified by absorption chromatography and submitted to HPLC analysis–DAD/ESI–MS. It was found that the bark is richer in simple phenols than the cashew apple meat.

Macleod and Troconis (1982) determined the volatile components in cashew apple using GC and GC/MS. The compounds identified encompass a variety of compound types, although terpene hydrocarbons (about 38%) as the major group. The group of terpenic hydrocarbons in the cashew essence consisted of four monoterpenes (about 34%) and three sesquiterpenes (about 4%).

The levels of carotenoids and ascorbic acid were analyzed by Assunção and Mercadante (2003) using HPLC and UV–visible spectrum in the red and yellow cashews apple from Brazilian Southeast and Northeast regions, respectively. Highly significant differences in the content of carotenoids and ascorbic acid were observed among the different cashew varieties of the two regions. The study concluded that cashew apple may be considered a good source of vitamin C, but not so good for pro vitamin A.

The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and healing capacity of mature and green cashew apple juice were evaluated by Vasconcelos et al. (2015) using Swiss mice. The results suggested that the green cashew apple juice presents a greater therapeutic activity due to the synergistic effect of its phytochemical components, which improve immunological mechanisms, as well as an optimal balance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidants, leading to a better process of wound healing.

Referring to the use of cashew apple as functional food, a study by Rani and Dodoala (2017) evaluated the antiobesity activity of the cashew ethanolic extract using the mouse model. The study showed that administration of cashew extract showed a significant decrease in total serum cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and VLDL cholesterol levels in the cashew extract treated groups. In addition, HDL-cholesterol levels also increased distinctly compared to obese control groups.

The cashew apple sugar content can range from 10 to 30% (Azam-Ali and Judge 2001). Due to its high sugar content, cashew apple juice is suitable as a source of reducing sugars for fermentative and enzymatic processes aiming at the production of lactic acid, dextran and oligosaccharides (Honorato et al. 2007; Silveira et al. 2012) as well as the production of ethanol (Khandetod et al. 2016; Arumugam and Ponnusami 2015; Talasila and Vechalapu 2015; Barros et al. 2014; Deenanath et al. 2012; Shenoy et al. 2011; Pinheiro et al. 2008).

Final remarks

The cashew culture is of great interest in the global scenario, which has been expanding in international markets in recent decades. Its production is concentrated in countries considered to be underdeveloped or developing, with the extraction and industrialization of its nuts being an important source of foreign exchange and exports for these countries. Cashew nuts has relevant healthy benefits, such as cancer prevention, cardiovascular protection, nerve protection, antioxidant action and vitamin source. Cashew apple also has healthy benefits such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, healing capacity and antiobesity activity. The cashew is a multipurpose plant and the present study allowed to map the potentiality of cashew nuts and cashew apple applications. It is an incentive for developing countries to invest in cashew agribusiness. The incorporation of systemic thinking in the integral use of cashew nut for the sustainable production of foods and products that have beneficial properties to health has shown to be a growing tendency in the industry due to the demand for natural products that favor the quality of life. It would be interesting to have a contribution between the food industries and researchers due to significant number of patents and papers published on cashew nut and cashew apple in recent years.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Studies (CAPES) for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nathalia Nogueira Oliveira, Email: nathaliaeq@yahoo.com.br.

Cheila Gonçalves Mothé, Email: cheila@eq.ufrj.br.

Michelle Gonçalves Mothé, Email: michelle@eq.ufrj.br.

References

- Abdul SM, Peter KV. Cashew, a monograph. New Delhi: Studium Press (India) Pvt. Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Akinhanmi TF, Atasie VN, Akintokun P. Chemical composition and physicochemical properties of cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale) oil and cashew nut shell liquid. J Agric Food Environ Sci. 2008;2(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwale TO. Cashew apple juice: its use in fortifying the nutritional quality of some tropical fruits. Eur Food Res Technol. 2000;211(3):205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Aremu MO, et al. Compositional studies and physicochemical characteristics of cashew nut (Anarcadium occidentale) flour. Pak J Nutr. 2006;5(4):328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Aremu MO, Ogunlade I, Olonisakin A. Fatty acid and amino acid composition of protein concentrate from cashew nut (Anarcadium occidentale) grownin Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Pak J Nutr. 2007;6(5):419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam A, Ponnusami V. Ethanol production from cashew apple juice using immobilized saccharomyces cerevisiae cells on silica gel matrix synthesized from sugarcane leaf ash. Chem Eng Commun. 2015;202:709–717. [Google Scholar]

- Assunção RB, Mercadante AZ. Carotenoids and ascorbic acid from cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale L.): variety and geographic effects. Food Chem. 2003;81(4):495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Azam-Ali SH, Judge EC (2001) Small-scale cashew nut processing. Food and Agriculture organization—FAO, Rugby. http://www.anacardium.info/IMG/pdf/Small-scale_Cashew_Nut_Processing_-_FAO_2001.pdf. Accessed 04 Apr 2019

- Barros EM, et al. A yeast isolated from cashew apple juice and its ability to produce first- and second-generation ethanol. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;174:2762–2776. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito ES, et al. Determination of the flavonoid components of cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale) by LC-DAD-ESI/MS. Food Chem. 2007;105(3):1112–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizicky GK. The genera of Anacardiaceae in the Southeastern United States. J Arnold Arbor. 1962;43:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Carestiato T, Aguila MB, Mothé CG. The effects of cashew gum as anti-hypertensive agent. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2009;97(2):717–720. [Google Scholar]

- Conab (2018) Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento https://www.conab.gov.br Accessed 01 Nov 2018

- Deenanath ED, Iyuke S, Rumbold K. The bioethanol industry in Sub-Saharan Africa: history, challenges, and prospects. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/416491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendena B, Corsi S. Cashew, from seed to market: a review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Embrapa . Cajueiro-anão-precoce. Fortaleza: Boletim informativo; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2018) The Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations http://www.fao.org/statistics/en. Accessed 01 Nov 2018

- Fitzpatrick J (2011) Cashew nut processing equipment study summary. http://www.africancashewalliance.com/sites/default/files/documents/equipment_study_ab_pdf_final_13_9_2011.pdf. Accessed 01 Nov 2018

- Freire FCO, et al. Diseases of cashew nut plants (Anacardium occidentale L.) in Brazil. Crop Prot. 2002;21:489–494. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann-Ribani R, Huber LS, Rodriguez-Amaya DB. Flavonols in fresh and processed Brazilian fruits. J Food Compos Anal. 2009;22(4):263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Honorato TL, Rabelo MC, Gonçalves LRB, Pinto GAS, Rodrigues S. Fermentation of cashew apple juice to produce high added value products. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;23(10):1409–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB, Manson JE, Willett WC. Types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:5–19. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBGE (2018) Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e estatística. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e estatístics. https://www.ibge.gov.br/. Accessed 01 Nov 2018

- Khandetod YP, Mohod AG, Shrirame HY (2016) Bioethanol production from fermented cashew apple juice by solar concentrator. In: Proceedings of the first international conference on recent advances in bioenergy research

- Khosla PK, Sareen TS, Mehra PN. Cytological studies on Himalayan Anacardiaceae. Nucleous. 1973;4:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lim TK. Anacardium occidentale. In: Lim TK, editor. Edible medicinal and nonmedicinal plants. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi A. Árvores brasileiras: manual de identificação e cultivo de plantas arbóreas nativas do Brazil. 4. Nova Odessa, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazi: Instituto Plantarum; 2004. p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Macleod AJ, Troconis NG. Volatile flavour components of cashew ‘apple’ (Anacardium occidentale) Phytochemistry. 1982;21(10):2527–2530. [Google Scholar]

- Mdic (2018) www.mdic.gov.br/comercio-exterior/estatisticas-de-comercio-exterior/comex-vis. Ministério da Indústria, Comercio Exterior e Serviços. Accessed 22 Aug 2018

- Medina JC, Bleinroth EW, Bernhardt LWEA. Caju – da cultura ao processamento e comercialização. Campinas: Instituto de tecnologia de Alimentos; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Melo JRT (2002) Fruticultura - Caju oferece emprego e renda nas longas estiagens. Revista Gleba - Informativo técnico

- Michodjehoun-Mestres L, et al. Monomeric phenols of cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale L.) Food Chem. 2009;112(4):851–857. doi: 10.1021/jf803174c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JD, Mori SA. The cashew and its relatives (Anacardium: Anacardiaceae) Mem N Y Bot Gard. 1987;42:1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira PAA. O cajueiro – vida, uso e estórias. Fortaleza: Editora Cristina Barbosa; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mothé CG, Correia DZ, Silva TC. Potencialidades do cajueiro. Rio de Janeiro: Publit; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mothé CG, de Freitas JS. Lifetime prediction and kinetic parameters of thermal decomposition of cashew gum by thermal analysis. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;131(1):397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Mothé CG, Oliveira NN, de Freitas JS, Mothe M. Cashew Tree Gum: A Scientific and Technological Review. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology. 2017;2(2):681–688. [Google Scholar]

- Nair KP. The agronomy and economy of important tree crops of the developing world. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva FFA, Garrutti DS, Neto RMS. Aproveitamento industrial do caju. Fortaleza: Embrapa-CNPAT/SEBRAE/CE; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Patil PJ. Indian cashew food. Integr Food Nutr Metab. 2017;4(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel CRM, Pessoa PFADP, Leite LADS (1998) Economia do caju. In: da Silva VV (ed) Caju. Cap 9, 2nd edn. Embrapa, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil, pp 214–220

- Pinheiro ADT, et al. Evaluation of cashew apple juice for the production of fuel ethanol. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2008;148:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s12010-007-8118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani TJPKVSRG, Dodoala S. Evaluation of antiobesity activity of ethanolic extract of cashew apple against high fat diet induced obesity in rodents. FASEB J. 2017;31(1 supplement):565. [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy D, et al. A study on bioethanol production from cashew apple pulp and coffee pulp waste. Biomass Bioenergy. 2011;35:4107–4111. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MS, Fontes CP, Guilherme AA, Fernandes FA, Rodrigues S. Cashew apple juice as substrate for lactic acid production. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012;5(3):947–953. [Google Scholar]

- Talasila U, Vechalapu RR. Optimization of medium constituents for the production of bioethanol from cashew apple juice using Doehlert experimental design. Int J Fruit Sci. 2015;15:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Tassara H. Frutas no Brasil. São Paulo: Editora Empresa das Artes; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos MS, et al. Anti-inflammatory and wound healing potential of cashew apple juice (Anacardium occidentale L.) in mice. Exp Biol Med. 2015;240(12):1648–1655. doi: 10.1177/1535370215576299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam M, Sathe SK. Chemical composition of selected ediblenutseeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:4705–4714. doi: 10.1021/jf0606959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]