Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the cholesterol removal capacity of seven metal–organic frameworks (MOF) and to compare with active carbon as adsorbents, and with aqueous β-cyclodextrine complexation removal technique. There were slight color differences in the oil samples after the treatments. The lowest free fatty acidities (0.13% and 0.13% linoleic acid) and peroxide values (21.07 and 23.50 meqO2/kg) were measured in aluminum-MOF (Al-MOF) and titanium-MOF (Ti-MOF) treated samples when compared to control sample (0.15%, and 27.62 meqO2/kg). Cholesterol reduction ratios of the Al-MOF treated sample (27.45%) and Ti-MOF treated sample (26.27%) were higher among all adsorbent treatments, but lower than that of the β-cyclodextrine aqueous complexation technique (33.07%). Further experiments with Al-MOF and Ti-MOF showed that when adsorbent addition level increased to 3.0%, removed cholesterol content increased. Likewise, when treatment times extended to 180 min, more cholesterol was removed. But, the removed cholesterol contents at 100 °C and 30 °C treatment temperatures were lower than that of at 50 °C treatment temperature. Further experiments with butter and sheep tail tallow showed that Al-MOF was quite effective as an adsorbent to remove cholesterol. This study proves the great potential of MOF to remove cholesterol selectively from oil/fat by adsorption principle.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Removal, Metal–organic framework, Peroxide value

Introduction

Cholesterol (3β-cholest-5-en-3-ol) is a common steroid named after the Greek words chole-(bile) and stereos-(solid) with alcohol suffix-ol. It is a lipid compound and synthesized by all animal cells. The main function of cholesterol in cells is to maintain fluidity and structure of cell membranes. In addition, it serves as the precursor for biosynthesis of steroid hormones, bile salts, and vitamin D. Although cholesterol is an essential component of all living cells, excess amounts of cholesterol in certain individuals may create some health problems. Literature indicated the correlation between higher serum cholesterol level and coronary heart diseases (Grundy et al. 1982; Li and Parish 1997). For humans, the external sources of cholesterol are dietary foods of animal origin like meat and meat products, dairy, animal fats, butter, eggs, fish and others. Therefore, lowering dietary intake of cholesterol has been suggested to lower serum cholesterol level (Sinha et al. 2015).

Although it would be easier to avoid foods of animal origin in diet, this might cause deficiencies of other nutrients. Hence, selective removal of cholesterol from high-cholesterol foods, while not changing nutritive and sensory properties of the foods has been perceived as a research challenge (Sun et al. 2018). There are many physical, chemical and biological techniques studied in literature to remove cholesterol from food sources. Some examples include blending with vegetable oil (Durkley 1982), organic solvent extraction (Larsen and Froning 1981), molecular distillation (Berti et al. 2018), adsorption with saponins (Micich 1990), extraction with high-methoxyl pectins (Rojas et al. 2007), degradation of cholesterol by cholesterol oxidizers (Dias et al. 2010), and adsorption on magnetic nanoparticles (Sun et al. 2018). However, in most of these methods difficulties such as higher cost, lower selectivity, loss of typical flavor and aroma, changes in rheological properties, and loss of other nutrients were encountered (Han et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2018).

The host–guest complexation with β-cyclodextrine is the most widely used method to remove cholesterol from foods. It is well known that β-cyclodextrine is edible, stable and relatively cheap, but it is hard to separate it from the food matrix (Dias et al. 2010; Tahir and Lee 2013). Hence, research challenges still exist to improve cholesterol removal techniques from foods.

Investigation of new adsorbents to selectively remove cholesterol from foods could be an important research topic, as hypothesized in this study. A new class of synthetic adsorbents, called metal–organic frameworks (MOF), have emerged for various applications including gas adsorption and storage, separation, sensors, magnetism, drug delivery, and selective adsorption applications (Stock and Biswas 2012; Furukawa et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2014). MOF are defined as the coordination polymers synthesized through chemical reactions of metal-containing units with organic linker molecules to yield open crystalline frameworks with permanent porosity and aesthetically interesting structures. There is limited number of studies reporting MOF applications in edible oils. In one of them (Li et al. 2015), one MOF was used to selectively adsorb and remove triazine and phenylurea herbicides from soy, sunflower, corn and peanut oils, and 87.3–107% recovery rates were achieved. In another study (Vlasova et al. 2016), three different MOFs were used to purify unrefined vegetable oils, and successive removal of free fatty acids, peroxides, and color pigments were reported. Both studies had not dealt with cholesterol adsorption and not measured cholesterol content of their samples.

Previously, in our laboratory, seven different MOFs were synthesized and characterized in terms of microstructure, crystallinity, surface and pore properties, thermal properties, some spectral properties, and free fatty acid and β-carotene adsorption capacities (Yilmaz et al. 2019). Furthermore, those MOFs and some natural clays were used to regenerate used frying oils in another study (Yilmaz and Güner 2018). We have also not measured cholesterol adsorption ability in our previous studies (Yilmaz et al. 2019; Yilmaz and Güner 2018). To the best of our knowledge, there is no study reporting MOF application to remove cholesterol from fats and foods.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the cholesterol removal ability of the MOFs, used as adsorbent materials, in a model oil. Furthermore, the well known β-cyclodextrine complexation method (Yen and Chen 2000) was also applied for comparison. After the treatments, common physico-chemical properties and remaining cholesterol contents of the treated and control oil samples were measured and compared with each other. Some process parameters like adsorbent addition level, adsorbent treatment temperature and time were also studied to determine the best conditions for the adsorption treatments. In addition, with the best performing adsorbents, cholesterol removal from butter and sheep tail tallow, which are the natural cholesterol sources, were studied.

Materials and methods

Materials

The seven different MOFs were previously synthesized in our laboratory at gram quantity, described with their structure and adsorbent properties (Yilmaz et al. 2019), and used in frying oil regeneration study (Yilmaz and Güner 2018). The same MOFs were used as adsorbent materials in this study. Briefly, MOFs used in the study were titaniumbutoxide-terephthalate MOF (Ti-MOF) synthesized by the method of Vlasova et al. (2016); gamma-cyclodextrine-potassium hydroxide MOF (γ-CD-MOF) synthesized according to Moussa et al. (2016); chrome nitrate-terephthalate MOF (Cr-MOF) synthesized following the method of Li et al. (2014); aluminum-MOF (Al-MOF) synthesized according to Ma et al. (2014); zinc nitrate-2,5-furandicarboxylic acid-MOF (Zn-MOF) synthesized by the solvothermal reaction described in Bu et al. (2012); magnesium-MOF (Mg-MOF) synthesized by modified technique of Spanopoulos et al. (2015); and zinc-2-methylimidazole zeolytic type MOF (ZIF-8-MOF) synthesized by the method of Park et al. (2006). Details of their synthesis methods and properties could be reached from the cited literature and from our previous studies (Yilmaz et al. 2019; Yilmaz and Güner 2018). The abbreviated MOF names given in the brackets above were used throughout the paper hereafter.

Active carbon powder (Zag Industrial Chemicals, Bereket Kimya Co., Istanbul, Turkey), β-cyclodextrine (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Steinheim, Germany), and cholesterol (95%, stabilized, Acros Organics Inc., Geel, Belgium) were purchased. Commercial refined–winterized sunflower oil, commercial butter and sheep tail tallow were bought from local stores. All solvents and chemicals used were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA) or Merck Co. (Darmstadt, Germany).

Preparation of the model oil

To prepare the model oil for adsorption experiments, 4.0 g of cholesterol was added into 1 kg of refined–winterized sunflower oil. The mixture was stirred on a magnetic stirrer at 300 rpm at 50 °C for 30 min to fully solubilize the added cholesterol. Then, this model oil was placed into a colored glass, flushed with nitrogen and capped tightly. Throughout the study, the oil was stored at ambient temperature and dark place.

Adsorbent treatments of the model oil

For each treatment, 50 g of model oil and each of the adsorbents (the seven MOFs and active carbon) were mixed at 1.5% (w/w) addition level, and then shaken in an incubator (Certomat IS, Sartorius Stedium Biotech, Germany) at 50 °C for 1.0 h with 350 rpm. Then the oil-adsorbent mixtures were centrifuged at 6461×g (Sigma 2-16K, Postfach, Germany) for 10 min. Finally, the treated oils were filtered through Whatman no. 1 filter paper (11 μ pore, 125 mm diameter) under gravity, and collected in colored glasses, flushed with nitrogen, capped and kept in the refrigerator throughout the analyses. Same procedure except adsorbent treatments was applied to control sample to eliminate other factors of the sample preparation procedure.

Aqueous β-cyclodextrine treatment of the model oil

The procedure of Yen and Chen (2000) was followed. 50 g of the model oil, 0.75 g (1.5%, w/w) of β-cyclodextrine and 100 ml distilled water were mixed. The mixture was stirred (350 rpm) at 50 °C for 1.0 h. Then, the slurry was centrifuged 6461×g for 10 min, and the aqueous layer was discarded. The oil phase was collected as the treated sample, placed in a colored glass, flushed with nitrogen, and capped before placing into refrigerator.

Physico-chemical properties of the treated oils

The instrumental color values of the L, a* and b* were measured with a CR-400 Minolta Colorimeter (Minolta Camera Co., Osaka, Japan). Oil refractive indices were measured with an Abbe 5 (Bellingham and Stanley, UK) refractometer at 25 °C.

Free fatty acidity and peroxide values were measured by AOCS methods of Ca 5a-40 and Cd 8-53 (AOCS 1998), respectively. The unsaponifiable matter content was measured by following ISO 3596 (ISO 2000) method.

Cholesterol analysis of the treated oils

The cholesterol contents of all oil samples were determined according to ISO 12228 methods (ISO 1999). First, the sterol fractions of the treated oil samples were separated by using thin layer chromatography (TLC), and then analyzed with Gas Chromatograph-FID (Agilent Technologies 7890B, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with DB5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.1 μm film thickness, J&W Scientific Co, CA, USA). The conditions of the analysis were as follows: oven temperature: 60 °C for 2 min, 60–220 °C (40 °C/min) for 1 min, 220–310 °C (5 °C/min) for 30 min, injection volume of 1 µl, injector split ratio of 1:100, flow rate of 0.8 ml/min, 30 ml/min hydrogen carrier gas, injector and detector temperatures of 290 °C and 300 °C, respectively. Commercial cholesterol standard was used for identification and quantification.

Effects of addition level, treatment temperature and time

After completion of the first part of the study, Ti-MOF and Al-MOF were selected as the best cholesterol removing adsorbents among all. With these two adsorbents, further experiments were done to determine the effects of adsorbent addition levels, treatment temperatures and times. Effects of low dosage (0.5%) and high dosage (3.0%) adsorbent additions were evaluated under the same treatment conditions described under the adsorbent treatments of the model oil section. Similarly, the effects of low (30 °C) and high (100 °C) temperature treatments under the same treatment conditions; and of shorter (30 min) and longer (180 min) treatment times under the same treatment conditions were investigated. After these treatments, only the cholesterol compositions of the samples were measured to select the best process parameters.

Treatments of butter and sheep tail tallow

From the findings of the model oil studies described above, the Ti-MOF, Al-MOF and β-cyclodextrine treatments were selected with the best performing process parameters (3.0% addition level, 50 °C treatment temperature, and 180 min treatment time) to apply for actual samples. Butter and sheep tail tallow were selected as the fat sources that contain cholesterol naturally. First, butter and sheep tail tallow were melted and their moisture was vaporized. After cooling, the samples were fully crystallized, and 50 g of each sample was melted again and treated with Ti-MOF, Al-MOF and β-cyclodextrine with the selected process parameters, described above. The same procedure, except adsorbent treatment, was applied to control sample. Finally, color, free fatty acidity and peroxide values, and cholesterol contents of the treated samples and their control samples were determined.

Statistical analysis

The whole study was replicated two times. The analyses for each replicate were completed three times. Collected data were given as means with standard errors. Comparison of the treatments for the measured oil properties was done by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s tests with the Minitab ver. 16.1.1 (Minitab 2010) program. There was a minimum 95% level of confidence for all statistical analyses.

Results and discussion

The physico-chemical properties of the treated oil samples

The treated and control oil samples were analyzed for some common physical properties, and the findings were presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference among the L values of the samples. The L values ranged between 23.55 and 25.86. Except active carbon treatment, all other treatments resulted significantly different a* values than the control sample (1.06). There was a shift toward negative a* values indicating a color change from redness to greenness. The highest change was observed in β-cyclodextrine treatment (− 1.14). On the other hand, there was no significant difference among the samples for the b* values, which indicate the intensity of yellowness in positive number direction and blueness in negative number direction. Clearly, the oil samples were moderately light, a little greenish, yellow samples. Since the model oil was prepared from refined–winterized sunflower oil, the color values were expected results. The refractive indices values of the samples were not different, and all was 1.452. No treatment had any effect on oil refractive index values. This finding also indicates that the treatments had not created any change in oil fatty acid compositions.

Table 1.

The physico-chemical properties of the control and treated (1.5% addition level, 1 h mixing, 50 °C) oil samples

| L | a* | b* | Refractive index (25 °C) | Free fatty acid (linoleic acid %) | Peroxide value (meqO2/kg) | Unsaponifiable matter (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 24.20 ± 0.04a | 1.06 ± 0.01a | 4.62 ± 0.05a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.15 ± 0.03a | 27.62 ± 0.88b | 14.85 ± 2.08a |

| Ti-MOF | 23.55 ± 0.03a | − 0.80 ± 0.04b | 4.51 ± 0.04a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.13 ± 0.02ab | 23.50 ± 1.85c | 12.47 ± 1.21b |

| γ-CD-MOF | 25.86 ± 0.17a | − 0.99 ± 0.06b | 4.04 ± 0.08a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.11 ± 0.02b | 23.95 ± 2.34c | 13.72 ± 1.85ab |

| Cr-MOF | 24.57 ± 0.36a | − 1.048 ± 0.03b | 3.88 ± 0.03a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 21.97 ± 1.88c | 12.65 ± 1.76b |

| Al-MOF | 23.93 ± 0.08a | − 0.94 ± 0.04b | 4.35 ± 0.01a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.13 ± 0.04ab | 21.07 ± 1.80c | 12.52 ± 2.02b |

| Zn-MOF | 24.59 ± 0.19a | − 1.11 ± 0.02b | 4.28 ± 0.02a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.14 ± 0.01a | 39.81 ± 0.92a | 12.40 ± 1.84b |

| Mg-MOF | 24.17 ± 0.45a | − 1.07 ± 0.01b | 4.62 ± 0.03a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.13 ± 0.01ab | 20.02 ± 0.93c | 12.80 ± 2.15b |

| ZIF-8-MOF | 24.47 ± 0.08a | − 1.07 ± 0.04b | 4.41 ± 0.01a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 21.38 ± 0.89c | 13.52 ± 1.92ab |

| β-Cyclodextrine | 24.89 ± 0.03a | − 1.14 ± 0.04b | 4.52 ± 0.05a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.12 ± 0.02b | 40.31 ± 3.07a | 11.20 ± 1.56bc |

| Active carbon | 24.04 ± 0.03a | 1.04 ± 0.04a | 3.68 ± 0.02a | 1.452 ± 0.00a | 0.12 ± 0.03b | 28.29 ± 1.38b | 14.08 ± 1.64a |

MOF, metal–organic framework; Ti, titanium; γ-CD, gamma-cyclodextrine; Cr, chromium; Al, aluminum; Zn, zinc; Mg, magnesium; ZIF-8, zeolitic type eight

*Small uppercase letters indicate the statistically significant differences within each column for the mean ± SD values calculated from four determinations by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

The free fatty acidity (FFA, %), peroxide (PV, meqO2/kg) values, and unsaponifiable matter contents (%) of the control and treated oil samples were given in Table 1. There were significant decreases in FFA values in all samples, except Ti-MOF, Al-MOF and Mg-MOF treatments. The highest reductions were observed in γ-CD-MOF (0.11%) and Cr-MOF (0.11%) treated samples when compared with control (0.15%) sample. Significant reductions in FFA of some other crude oils (Vlasova et al. 2016), and used frying oils (Yilmaz and Güner 2018) treated with various MOFs were previously published, so this is a quite expected finding. Free fatty acids as carboxylic acids could interact with basic proton acceptor or Lewis centers present in the MOF structure to be adsorbed and removed from bulk oil. Except, Zn-MOF and β-cyclodextrine treatments, all other treatments reduced the PV of the model oil. The PV of control sample was 27.62 meqO2/kg, and it was reduced to the lowest value of 20.02 meqO2/kg by Mg-MOF treatment. Further, Cr-MOF, Al-MOF and ZIF-8-MOF treated samples had lower PV values. Among the MOFs, only Zn-MOF treatment caused PV to increase to 39.81 meqO2/kg value. Most importantly, β-cyclodextrine treatment resulted in very significantly higher PV (40.31 meqO2/kg). This might be due to the aqueous process, and could be accepted as one of the negative aspect in comparison to the MOF adsorbent treatments. Hence, for all treatment types, vacuum or nitrogen gas atmosphere during the treatments were suggested to control oil oxidation. The unsaponifiable matter contents of the samples indicated that except active carbon treatment, all treatments yielded some decreases (Table 1). Since the model oil was prepared from refined–winterized sunflower oil, the important portion of the unsaponifiable matters should be originated from the added cholesterol. Of course, some other minor components present in the oil could add up to this contents.

Since the focus of this study was to evaluate the cholesterol removal capacity of the MOFs as adsorbents, effects of the adsorbent treatments on other oil minor components like tocols, pigments and phytosterols were not measured. In our previous study with regeneration of used frying oils (Yilmaz and Güner 2018), some adsorption abilities for polar materials were proved. Similarly, β-carotene adsorption ability of the MOFs was observed in our other previous study (Yilmaz et al. 2019).

The cholesterol content of the treated oil samples

The cholesterol content and percent cholesterol reduction values, based on the calculation over the control sample, were presented in Table 2. In the control oil, 382.5 mg cholesterol/100 g oil was determined. Actually this was lower than the added amount (400 mg/100 g). Since control oil was also incubated, centrifuged and filtered (but not treated with adsorbents) under the same conditions of the treated oil samples, this much change could be due to these routine operations or due to the level of purity (85%) of the added cholesterol. Since the percent reduction values were calculated over this measured value of the control sample, this difference has been already countered. Among all treatments, standard β-cyclodextrine extraction technique yielded the lowest remaining cholesterol (256.5 mg/100 g) with a 33.07% total reduction rate. Among the adsorbent treatments, the highest reduction values were observed in Al-MOF (27.45%) and Ti-MOF (26.27%). Although γ-CD-MOF contained gamma-cyclodextrine within its structure, it was not quite effective in reducing cholesterol with 12.68% reduction rate. Clearly, selective cholesterol adsorption from liquid oil media is mostly governed by the microstructure and/or presence of high affinity groups within the MOF structure. The chemical mechanism of cholesterol-MOF interactions were not investigated in this study, and remains as a research question. Since the addition level, mixing time and temperatures were the same among all treatments, higher effectiveness of β-cyclodextrine could be due to both its higher affinity towards cholesterol and its aqueous slurry type administration to the oil. Still, the efficient MOFs could have importance for practical applications due to some other reasons. First, application of adsorption process is much simpler than the application of aqueous β-cyclodextrine complexation treatment. Second, any aqueous treatments applied to oils usually yields emulsions which results in massive oil losses. And third, MOF adsorbent treatments yielded better peroxide values and free fatty acidities than those of the β-cyclodextrine treatment, so, β-cyclodextrine treatment requires additional refining processes to remove the peroxides.

Table 2.

The cholesterol content of the control and treated (1.5% addition level, 1 h mixing, 50 °C) oil samples

| Cholesterol (mg/100 g) | Reduction (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 382.5 ± 2.1a | – |

| Ti-MOF | 282.0 ± 0.7f | 26.27 |

| γ-CD-MOF | 334.5 ± 1.0b | 12.68 |

| Cr-MOF | 287.0 ± 0.7e | 25.00 |

| Al-MOF | 277.5 ± 1.0f | 27.45 |

| Zn-MOF | 308.0 ± 4.2d | 19.48 |

| Mg-MOF | 304.5 ± 0.7d | 20.39 |

| ZIF-8-MOF | 290.0 ± 1.4e | 24.18 |

| β-Cyclodextrine | 256.5 ± 1.4g | 33.07 |

| Active carbon | 319.0 ± 1.4c | 16.60 |

Percent reduction values calculated over the control sample

MOF, metal–organic framework; Ti, titanium; γ-CD, gamma-cyclodextrine; Cr, chromium; Al, aluminum; Zn, zinc; Mg, magnesium; ZIF-8, zeolitic type eight

*Small uppercase letters indicate the statistically significant differences within each column for the mean ± SD values calculated from four determinations by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Although there are studies with various β-cyclodextrine treatments to remove cholesterol from different foods (Yen and Chen 2000; Dias et al. 2010; Tahir and Lee 2013; Tahir et al. 2015), studies involving adsorption principle (Chen et al. 2015; Inanan et al. 2016; Sun et al. 2018) are rather limited. Yen and Chen (2000) showed that fractionation and refining of lard helped to remove cholesterol by β-cyclodextrine, and around 90% of removal was achieved with 4% addition level. In present study, cholesterol removal ratio was only 33.07% with 1.5% β-cyclodextrine addition level. In another study (Dias et al. 2010), β-cyclodextrine was applied with co-precipitation, kneading, and physical mixture techniques to butter to remove cholesterol, and averages of 90.96%, 27.58%, and 16.81% removals were achieved. Tahir et al. (2015) showed that glass surface functionalized with β-cyclodextrine removed cholesterol from ghee with 78.8% effectiveness. Clearly, effectiveness of β-cyclodextrine in cholesterol removal is heavily depended on the techniques utilized. Finely grinded okra powder was shown to adsorb cholesterol by around 80% (Chen et al. 2015). Inanan et al. (2016) showed that molecularly imprinted polymers prepared using cholesterol as template and N-methacryloylamido-(L)-phenylalanine methyl ester adsorbed cholesterol at 714.17 mg/g capacity, and it was recycled effectively for 5-times with only 12.28% decrease in adsorption capacity. This seems a quite good achievement. Lastly, Sun et al. (2018) used magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with carboxylated β-cyclodextrin to selectively adsorb cholesterol from milk and egg yolk. Using the nanoparticles and saponified milk and egg yolk, 98.8% and 94.6% of the cholesterol was extracted in 1 h, respectively.

Overall, MOFs as adsorbents to remove cholesterol from edible oils/fats showed a good potential, and the treatment could be improved to enhance its effectiveness by creating some functional chemical groups within the MOF structure. This area could also open new research challenges to be studied further. It is well known from the MOF literature that synthesis chemist could post-modify MOF structures to include selective affinity groups for targeted chemicals (Stock and Biswas 2012; Furukawa et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2014).

Effects of adsorbent addition level, treatment temperature and time

Among all adsorbents, Al-MOF and Ti-MOF were selected to study the effects of adsorbent addition levels, treatment temperatures and times. Figure 1 shows the remaining cholesterol contents of the model oil treated with the two selected MOFs at 0.5, 1.5, and 3.0% addition levels. Clearly, for both MOFs, as addition level increased, adsorbed cholesterol level increased linearly. Hence, depending upon the price and reusability of the MOFs, higher addition levels could be used for more efficient cholesterol removal.

Fig. 1.

The effects of adsorbent addition level on the cholesterol adsorption capacity of the selected adsorbents

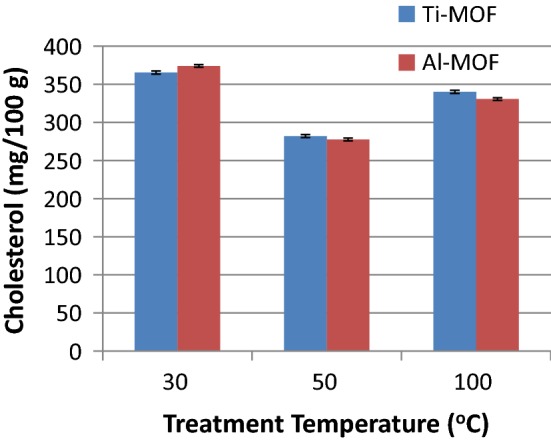

Similar experiments were completed with different treatment temperatures (Fig. 2). Under the same addition level (1.5%) and other process parameters, only the treatment temperature was changed. Interestingly, the best results were obtained at 50 °C, and increasing temperature to 100 °C or lowering to 30 °C during the adsorbent mixing at the same treatment time (1.0 h) yielded lower cholesterol removals. Clearly at lower and higher temperatures, cholesterol adsorption capacity of the MOFs become lower than those measured at 50 °C. This might be due to changes in cholesterol solubility and/or durability of adsorbed cholesterol on the MOF surface. At lower temperatures, the cholesterol may not be enough soluble to penetrate into the MOF surfaces, or there might not be enough kinetic energy to yield effective adsorptions. At higher temperatures, it would be probable that, some affinity losses might have occurred or due to higher solubility and kinetic energy, adsorbed cholesterol became easily soluble and dissolve back into the oil.

Fig. 2.

The effects of adsorbent treatment temperatures on the cholesterol adsorption capacity of the selected adsorbents

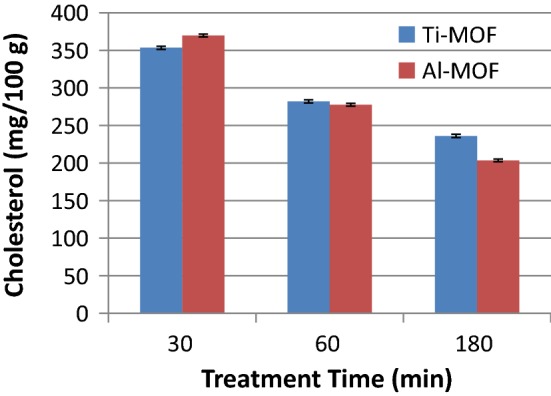

Lastly, the effect of treatment time under the same treatment conditions were investigated (Fig. 3). Clearly, as treatment time enhanced from 30 min to 180 min, the cholesterol removal rate increased. This experiment was done only with three selected treatment times as the most common duration ranges of industrial adsorbent applications in edible oil sector, and selection of longer treatment times must be judged with increasing the process cost.

Fig. 3.

The effects of treatment time on the cholesterol adsorption capacity of the selected adsorbents

Overall, Al-MOF and Ti-MOF could be effective adsorbents to remove cholesterol from liquid oils at 3.0% addition level, 50 °C treatment temperature for 3.0 h. Further, applications of vacuum or nitrogen gas atmosphere during the process was suggested to prevent oxidative deteriorations of the oil during the treatment.

Cholesterol removal from butter and sheep tail tallow

Butter and sheep tail tallow were treated with Ti-MOF, Al-MOF and β-cyclodextrine against their control samples, and the results of some analyses were provided in Table 3. Clearly, like model oil, the treatments resulted some significant but little changes in the color values of the oils. Reduction of the FFA was most significant in Al-MOF treatment for both oil samples, while PV reduction was better with Ti-MOF treatment. Further, unlike the model oil, β-cyclodextrine treatment of these animal fats did not result in enhancements of FFA or PV. Clearly, nature of the oil was quite effective in the oil stability during the treatments. The cholesterol content of butter (90.43 mg/100 g) was most reduced by Al-MOF treatment (56.71 mg/100 g), which corresponds about 37.29% reduction. It was also higher than that of the β-cyclodextrine treatment (25.68%). Similarly, cholesterol content of the sheep tail tallow was 281.64 mg/100 g, and most reduced by Al-MOF treatment to 213.58 mg/100 g, which corresponds 24.16% reduction rate. Overall, under the same treatment conditions, the Al-MOF was very successful in removing cholesterol from butter and sheep tail tallow.

Table 3.

Properties and cholesterol contents of the butter and sheep tail tallow samples treated with the selected adsorbents

| L | a* | b* | Free fatty acid (palmitic acid %) | Peroxide value (meqO2/kg) | Cholesterol (mg/100 g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butter sample | ||||||

| Control | 22.95 ± 0.04b | − 1.08 ± 0.06a | 5.17 ± 0.03a | 0.74 ± 0.01a | 13.89 ± 0.07a | 90.43 ± 2.01a |

| Ti-MOF | 22.60 ± 0.04b | − 1.04 ± 0.04a | 4.54 ± 0.05b | 0.75 ± 0.12a | 7.48 ± 1.81b | 81.95 ± 1.10b |

| Al-MOF | 22.13 ± 0.05b | − 0.60 ± 0.03b | 3.80 ± 0.01c | 0.59 ± 0.12b | 7.65 ± 1.80b | 56.71 ± 0.13d |

| β-Cyclodextrine | 23.05 ± 0.09a | − 1.22 ± 0.60a | 4.54 ± 0.05b | 0.68 ± 0.01b | 7.42 ± 0.29b | 67.21 ± 2.03c |

| Sheep tail tallow sample | ||||||

| Control | 23.48 ± 0.02a | − 0.23 ± 0.07b | 8.49 ± 0.04a | 0.74 ± 0.03a | 11.42 ± 0.46a | 281.64 ± 0.90a |

| Ti-MOF | 23.67 ± 0.02a | − 0.40 ± 0.01a | 8.62 ± 0.06a | 0.57 ± 0.06b | 6.62 ± 0.89b | 217.18 ± 0.28b |

| Al-MOF | 22.60 ± 0.06b | − 0.35 ± 0.03a | 8.14 ± 0.03a | 0.48 ± 0.11b | 9.04 ± 1.11a | 213.58 ± 1.70b |

| β-Cyclodextrine | 21.64 ± 0.12c | − 0.26 ± 0.04b | 8.70 ± 0.11a | 0.58 ± 0.04b | 6.28 ± 0.49b | 214.63 ± 2.06b |

Ti-MOF, titanium metal–organic framework; Al-MOF, aluminum metal–organic framework

*Small uppercase letters indicate the statistically significant differences within each column for the mean ± SD values calculated from four determinations by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Conclusion

In this study, selected MOFs were evaluated as adsorbent materials to remove cholesterol from a model oil prepared by adding external pure cholesterol into sunflower oil. The MOFs were compared with active carbon as a regular adsorbent, and with standard aqueous β-cyclodextrine treatment, under the same conditions. Cholesterol reduction rate of Al-MOF (27.45%) and Ti-MOF (26.275) were higher than the rest of the adsorbents, but lower than β-cyclodextrine treatment (33.07%). On the other hand, peroxide and free fatty acidity values of the MOF treated samples were much better than those of the β-cyclodextrine treated sample. Further, experiments with butter and sheep tail tallow proved that Al-MOF was the best in removing cholesterol. Hence, an utilizable potential of the MOFs to remove cholesterol by adsorption principle is proved. Actually MOFs are designed materials, and it would be quite possible to design new MOF structures having higher affinity towards cholesterol to selectively adsorb it from different media. This study provides the first data about application of the MOF for this purpose, and opens up a new research gate for further studies. Previous studies of MOF applications for edible oils (Vlasova et al. 2016; Yilmaz and Güner 2018) indicated no metal leaking from the MOF structures into the oil, and indicated that the process was safe. Overall, this study proves an important potential of some MOFs to remove cholesterol from oils by adsorption principle.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- AOCS . Official methods and recommended practice of the American Oil Chemist’s Society. 5. Champaign, IL: American Oil Chemist’s Society; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Berti J, Grosso NR, Fernandez H, Gayola MC, Pramparo MC, Gayol MF. Sensory quality of milk fat with low cholesterol content fractioned by molecular distillation. J Sci Food Agric. 2018;98:3478–3484. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu F, Lin Q, Zhai Q, Wang L, Wu T, Zheng S-T, Bu X, Feng P. Two zeolite-type frameworks in one metal–organic framework with Zn24@Zn104 cube-in-sodalite architecture. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:8538–8541. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhang B-C, Sun Y-H, Zhang J-G, Sun H-J, Wei Z-J. Physicochemical properties and adsorption of cholesterol by okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) powder. Food Funct. 2015;6:3728–3736. doi: 10.1039/C5FO00600G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias HMAM, Berbicz F, Pedrochi F, Baesso ML, Matioli G. Butter cholesterol removal using different complexation methods with beta cyclodextrin, and the contribution of photoacoustic spectroscopy to the evaluation of the complex. Food Res Int. 2010;43(4):1104–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durkley WL. Reducing fat in milk and dairy products by processing. J Dairy Sci. 1982;65(3):454–458. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(82)82214-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H, Cordova K, Keeffe M, Yaghi O. The chemistry and applications of metal–organic frameworks. Science. 2013;341:123–444. doi: 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Brheimer D, Blackburn H, Virgil BW, Kwiterovich PO, Mattson F, Schonfeld G, Weidman WH. Rationale of the diet-heart statement of the American Heart Association Report of the Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 1982;65:839A–854A. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.65.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han EM, Kim SH, Ahn J, Kwak HS. Comparison of cholesterol reduced cream cheese manufactured using crosslinked β-cyclodextrin to regular cream cheese. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2008;21(1):131–137. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2008.70189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inanan T, Tüzmen N, Akgöl S, Denizli A. Selective cholesterol adsorption by molecular imprinted polymeric nanospheres and application to GIMS. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO . International Standards Official Methods 12228:1999. Animal and vegetable fats and oils-determination of individual and total sterols contents—gas chromatographic method. Geneva: International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- ISO . Animal and vegetable fats and oils: determination of unsaponifiable matter—method using diethyl ether extraction. Geneva: International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JE, Froning GW. Extraction and processing of various components from egg yolk. Poult Sci. 1981;60(1):160–167. doi: 10.3382/ps.0600160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Parish EJ. The chemistry of waxes and sterols. In: Min DB, Akoh CC, editors. Food lipids: chemistry, nutrition, and biotechnology. 1. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Wang Z, Zhang L, Nian L, Lei L, Ynag X. Liquid-phase extraction coupled with metal–organic frameworks-based dispersive solid phase extraction of herbicides in peanuts. Talanta. 2014;128:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang L, Nian L, Cao B, Wang Z, Lei L, Yang X, Sui J, Zhang H, Yu A. Dispersive micro-solid-phase extraction of herbicides in vegetable oil with metal–organic framework MIL-101. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:2154–2161. doi: 10.1021/jf505760y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Lin J, Xue Y, Li J, Huang Y, Tang C. Acid-assisted hydro thermal synthesis and adsorption properties of high-specific-surface metal–organic frameworks. Mater Lett. 2014;132:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Micich TJ. Behaviors of polymer-supported digitonin with cholesterol in the absence and presence of butter oil. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38(9):1839–1843. doi: 10.1021/jf00099a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minitab . Minitab Statistical Software (Version 16.1.1) State College, PA: Minitab Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa Z, Hmadeh M, Abiad MG, Dib OH, Patra D. Encapsulation of curcumin in cycodextrin-metal organic frameworks: dissociation of loaded CD-MOFs enhances stability of curcumin. Food Chem. 2016;212:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KS, Ni Z, Cote AP, Choi JY, Huang R, Uribe-Romo FJ, Chae HK, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi O. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic ımidazolate frameworks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(27):10186–10191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602439103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas EEG, Coimbra JSR, Minim LA, Freitas JF. Cholesterol removal in liquid egg yolk using high methoxyl pectins. Carbohydr Polym. 2007;69(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Basiruddin SK, Chakraborty A, Jana NR. ß-Cyclodextrin functionalized magnetic mesoporous silica colloid for cholesterol separation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:1340–1347. doi: 10.1021/am507817b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanopoulos I, Bratsos I, Tampaxis C, Kourtellaris A, Tasiopoulos A, Charalambopoulou G, Steriotis TA, Trikalitis PN. Enhancedgas-sorption properties of a high surface area, ultramicroporous magnesium formate. CrystEngComm. 2015;17:532–539. doi: 10.1039/C4CE01667J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stock N, Biswas S. Synthesis of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs): routes to various MOF topologies, morphologies, and composites. Chem Rev. 2012;112(2):933–969. doi: 10.1021/cr200304e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xu B, Mu Y, Ma H, Qu W. Functional magnetic nanoparticles for highly efficient cholesterol removal. J Food Sci. 2018;83(1):122–128. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir MN, Lee Y. Immobilisation of β-cyclodextrin on glass: characterisation and application for cholesterol reduction from milk. Food Chem. 2013;139:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir MN, Bokhari SA, Adnan A. Cholesterol extraction from ghee using glass beads functionalized with beta cyclodextrin. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(2):1040–1046. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-1039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlasova EA, Yakimov SA, Naidenko EV, Kudrik EV, Makarov SV. Application of metal–organic frameworks for purification of vegetable oils. Food Chem. 2016;190:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen GC, Chen C-J. Effects of fractionation and the refining process of lard on cholesterol removal by β-cyclodextrin. J Food Sci. 2000;65(4):622–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb16061.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz E, Güner M. Regeneration of used frying oils by selected metal–organic frameworks as adsorbents. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2018;95(12):1497–1508. doi: 10.1002/aocs.12144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz E, Erden A, Güner M. Structure and properties of selected metal organic frameworks as adsorbent materials for edible oil purification. Riv Ital Sostanze Grasse. 2019;96(3):25–38. [Google Scholar]