Abstract

Postharvest technologies, such as the application of coatings, could contribute to the extension of the shelf life of avocado fruit. The objective of the present research was to evaluate the effects of coating, based on agro-industrial co-products (citrus pectin, broken rice grain flour, and cellulosic rice skin nanofiber), sorbitol and potassium sorbate, on the quality of avocado (cultivar ‘Quintal’) stored under refrigeration. The coating contributed to a longer conservation of the green color of avocado, both peel and pulp, and significantly reducing the respiration rate of the coated fruit, which was 35% lower than that of the control fruit. The coated fruit was firmer and, possibly, the addition of cellulosic nanofiber contributed to the maintenance of this firmness. Regarding the bioactive compounds, there was no difference (p > 0.05) among the coated and control fruit. During refrigerated storage, total phenolic compounds content increased (p < 0.05) from 311.44 ± 25.89 to 800.25 ± 160.74 mg kg−1 gallic acid equivalents (GAE) in the control fruit, and from 242.86 ± 52.33 to 584.75 ± 125.57 mg kg−1 GAE in the coated fruit. It was concluded that the shelf life of avocado (cultivar ‘Quintal’) could be extended and ripening delayed by a minimum of 8 days, by applying a coating formulated with rice flour, pectin, sorbitol, potassium sorbate, and cellulosic rice skin nanofiber.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-019-04039-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Persea americana Mill., Respiration rate, Firmness, Antioxidant activity, Phenolic compounds

Introduction

Coatings should be safe to be used on foods, biodegradable and, in general, based on biological materials, such as proteins, lipids and polysaccharides, which can be found in agro-industrial co-products. The most used coatings materials are starch, cellulose and pectin, which are generated during industrial food processing. These materials can be considered safe as long as they are handled properly. Their application contributes to reducing the food industry’s environmental impact. Besides that, from the economic point of view, these materials are viable (Oliveira et al. 2019).

Rice skin (source of cellulose) and broken rice grains (source of starch and proteins) are generated during industrial rice processing. Rice skin can be processed into cellulosic nanofibers, which can become promising materials to be incorporated in coatings. This happens due to the dispersion and reinforcements in the matrix of starch and pectin biopolymers. Since nanofibers are materials with low aggregated value and high performance, they constitute a promising industrial technological advance (Ghaderi et al. 2014). Such co-products, after an adequate preparation, can constitute the matrix of coatings, together with sorbitol (plasticizer) and potassium sorbate (antimicrobial action), additives which contribute to improving the properties of coatings during post harvesting.

Active coating is defined as the beneficial interaction of the coating, product and environment, to prolong the shelf life or increase the sensorial or safety properties of the fruits, preserving the desirable quality for commercialization and consumption. The incorporation of potassium sorbate in the coatings contributes to antimicrobial activity, extending the lag phase and reducing the growth of microorganisms, preserving thus, the quality and safety of the product, and prolonging the shelf life.

Coatings have attracted the attention of producers, merchants and researchers, as they represent an innovative technology for extending the commercial shelf life of foods, especially that of fruits and vegetables. This is done by functioning as a barrier to water vapor and gases, and in most cases, acting as a modified atmosphere package. The coating creates a barrier to slow respiration rate and, consequently, modify carbon dioxide (CO2) and oxygen (O2) concentrations, by changing the internal conditions of the coated fruit and extending the shelf life or improving safety or quality (Hashemi and Khaneghah 2017; Kumar et al. 2019).

The avocado tree (Persea americana Mill.) is considered to be an economically important cultivar. The fruit has a climacteric respiratory pattern with a high respiration rate. It is ethylene sensitive and susceptible to latent infections after harvest, and physiological disorders, generally associated with refrigeration damage. For the fruit to reach more distant markets for quality, conservation is necessary. Since it is highly perishable, the avocado has a short shelf life, which could be extended by the use of postharvest technologies (Schaffer et al. 2013).

Conservation under refrigeration is the most commonly employed method and the storage temperature varies from cultivar to cultivar. ‘Quintal’ avocados can be stored at 7–10 °C, which is considered as safe temperature (Yahia and Woolf 2011). This fruit is rich in monounsaturated fatty acids (Cowan and Wolstenholme 2016) and total phenolic compounds, and has a high antioxidant capacity (Wang et al. 2010). ‘Quintal’ is represented by large-sized fruits, containing approximately 82% of butter-type pulp and is ideal to be consumed in natura. These fruits have a low calorie content when compared to other cultivars, all characteristics responsible for the high commercial value of the fruit (Silva et al. 2014).

There is a lack of information about the use of coatings formulated from agro-industrial co-products (pectin, broken rice grain flour and cellulosic rice skin nanofiber), sorbitol and potassium sorbate, on fruits. Thus, the objective of this research was to evaluate the effect of the formulated coating on the quality of the ‘Quintal’ avocado. Although the world market of ‘Quintal’ avocado is limited, this study can serve as basis for other cultivars.

Materials and methods

Materials

‘Quintal’ avocados were manually harvested at the commercial point of ripeness—early ripe stage, emerald green colour and firm texture—from a small holding in the municipality of Lavras (Minas Gerais, Brazil). Around 250 fruits were selected, with an average mass of 485.11 ± 62 g and measurements of 12.43 ± 0.97 cm (longitudinal axis) and 9.16 ± 0.47 cm (transversal axis), with a uniform color and no damage caused by mechanical action, wilting or the presence of fungi. They were then transported to the laboratory, washed, sanitized (100 mg L−1 sodium hypochlorite/15 min), rinsed (200 mg L−1 sodium hypochlorite), dried at 25 °C and randomly split into two groups (non-coated control fruits and coated fruits).

Cellulose was extracted from rice skin, according to Johar et al. (2012), with modifications. After extraction, 1.5% solution of cellulose was processed in a mechanical grinder defibrillator (Super Masscolloider®, MKCA6-2J, Kawaguchi, Japan) operated at 1500 rpm with a 0.01 mm gap between the disks. Cellulosic nanofiber from rice skin was obtained after 25 passes through the defibrillator.

Coating preparation and application

The filmogenic solution used to make the coating was defined according to previous tests, which allowed the selection of the film that promoted the highest values of mechanical properties and the lowest of water vapor permeability and opacity (data not shown). Thus, the filmogenic solution was prepared with 5 g of broken rice grain flour, standardized by using a 0.177 mm sieve, 5 g citrus pectin, 25 mL of a 70% sorbitol solution, 3 mL cellulosic rice skin nanofiber, 2 mL of a 0.1% potassium sorbate solution and 100 mL of distilled water. The mixture was heated under constant stirring, until gelatinization of the rice flour starch and dissolution of the pectin. The fruits to be coated were immersed in the filmogenic solution at 20 °C for 2–3 min, so that the coating was uniformly distributed over the surface of the fruit. The avocados of the control group were just immersed in distilled water and allowed to dry naturally. When dry, the fruits were placed in expanded polystyrene trays, one fruit per tray, and stored at a safe temperature of 10 ± 2 °C and relative humidity of 65–85% (Yahia and Woolf 2011). The humidity and temperature of the air were monitored, using a digital thermo-hygrometer (JPROLAB, SH 122, Brazil).

The storage trials used an entirely random factorial design, with three repetitions per treatment and nine fruits per repetition. The respiration rate and mass loss of the fruit were evaluated on a daily basis for ten consecutive days, under refrigerated storage. Physical and chemical variables were evaluated over 20 days under refrigerated storage, every 4 days.

Physiological, physical and chemical characteristics evaluated

Respiration rate

The respiration rate was determined in a closed system with the aid of a gas analyzer (PBI Dansensor, MAP Mix 9000, Ringted, Denmark) and the results expressed in μg kg−1 s−1 CO2.

Mass loss

The mass loss (%) was determined for 15 fruits from each treatment. Each fruit was weighed and mass loss calculated, considering the difference between the initial mass of the fruit and the mass obtained at each sampling time interval during the 10 days of analysis.

Color

The instrumental color parameters of fruit´s peel and pulp were determined with a colorimeter (Konica Minolta, CR-400, Osaka, Japan) in CIE mode D65. Parameters analyzed were L* (Lightness) varying from dark/opaque to white, a* (green/red), b* (blue/yellow), C* (Chroma; color saturation/color intensity) and h° (hue angle), which represents the color ranging from blue (270°) to green (180º) to yellow (90°) and purple-red (0°). All these values were directly read from the colorimeter. Three readings from each fruits were taken from different points on the peel and pulp. Photographs were taken daily to follow up the fruits’ peel appearance.

Chlorophyll contents

Extracts for the determinations of the total chlorophyll, A chlorophyll and B chlorophyll contents of the fruit pulps were prepared, according to Watada et al. (1990) and quantified, according to the methodology described by Engel and Poggiani (1991).

Firmness

Firmness was determined individually, for the whole fruit. The measurements were being made in the equatorial region at three equidistant points with the aid of a manual digital Fruit Hardness Tester (Instrutherm, PTR-300, São Paulo, Brazil), using a 5 mm diameter probe, which was manually punctured (9 mm depth). The results were expressed in Newton (N) (Nakatsuka et al. 2011).

Total and soluble pectin and total sugars content

Total and soluble pectin, and total sugars were extracted, according to the technique of McCready and McComb (1952). The total and soluble pectin were quantified, using the technique of Bitter and Muir (1973), and the total sugars, using the Anthrone spectrophotometric method of Dische (1962).

Total ascorbic acid, phenolic and antioxidant content

Total ascorbic acid was determined according to Strohecker and Henning (1967).

Phenolic and antioxidant compounds were extracted, according to Larrauri et al. (1997). The total phenolic compounds were quantified by the Folin–Ciocalteau colorimetric method, with some modifications, as described by Waterhouse (2002).The antioxidant activity was determined, using the methods of β-carotene/linoleic acid, according to the methodologies described by (Rufino et al. 2007).

Statistical analysis

The data obtained was submitted to a factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), and mean comparisons and regression models were fitted (p ≤ 0.05) for each response, using the software Statistica10.0 (StatSoft Inc. 2010). The graphs were plotted with the aid of the Microsoft Excel 3.0.

Results and discussion

According to the statistical analysis, the variables hº (peel and pulp), firmness, soluble and total pectin, total sugars, ascorbic acid, total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity (β-carotene/linoleic acid methods) were significantly (p < 0.05) affected by the interaction between coating and storage period factors. The other variables were not affected (p > 0.05) by the interaction between factors, although the respiration rate, mass loss, and chlorophyll A content were influenced (p < 0.05) by the coating and the storage period factors individually, and chlorophyll total and B chlorophyll contents just by the storage period. Color L* and C* were not affected (p > 0.05) by any factor.

In order to obtain mathematical models capable of explaining the effects of variables, the coefficient of determination (R2, R2 adjusted), p value, and F test were analyzed to understand the real meaning of each factor in the model tested. The models were evaluated only when R2 > 0.7, p < 0.05, and F calculated (Fc) > F tabulated (Ft). Respiratory rate and mass loss showed Ft = 2.393, and for the other variables Ft = 3.106. Fc is presented in the respective tables (Supplementary material).

The respiration rate of avocados, in spite of coating, increased in the first 2 days and the last 4 days of the storage, with a stationary phase between two and six (Fig. 1a). However, the coating promoted a reduction in the respiration rate of the fruit of about 45%. The mass loss of avocado fruit increased over the storage period linearly up to the tenth day (Fig. 1b). Coated fruit had a lower (p < 0.05) mass loss compared to control fruit.

Fig. 1.

The effect of a coating based on agro-industrial coproducts (citrus pectin, broken rice grain flour and cellulosic nanofibers from the rice skin), sorbitol and potassium sorbate on ‘Quintal’ cultivar avocados, and of the refrigerated storage time (10 ± 2 °C and 65–85% RH) on respiratory rate (a) and mass loss (b). Diamond: control fruit; square: coated fruit

The results of respiration rate observed in the present research were similar to those reported by Tesfay and Magwaza (2017) for avocado fruits of the cultivars ‘Hass’ and ‘Fuerte’, where respiration rate increased with storage period, but was always lower in the fruit coated with a mixture of moringa leaf extract, chitosan and carboxymethylcellulose.

Coutinho et al. (2015) reported that avocados without coating lost approximately 50% of their initial mass after 9 days of storage at room temperature, whereas those coated with 1% and 3% potato starch, lost only 40% and 30%, respectively. Their values were much higher than those reported in the present study, probably due to the effect of the storage temperature and the inferior water barrier characteristics of potato starch in relation to the coating used in the present research.

The coating partially fills the apertures present in the dermal tissue, acting significantly in the reduction of gas exchange or respiration. The coating can create an internal modified atmosphere, which, at the beginning of the period postharvest, can increase the respiratory rate. Later, when internal atmosphere is stabilized, the fruit reduces its respiration rate and, consequently, its metabolism, slowing the fruit ripening. In aerobic respiration, glucose is burned in the presence of O2, generating energy, CO2 and water. Thus, the success of coating in decreasing the respiration rate and, consequently, mass loss, was proved. Coatings block, in part, natural openings of the fruit, creating a partial barrier to gases, acting as a modified atmosphere package (Hashemi and Khaneghah 2017).

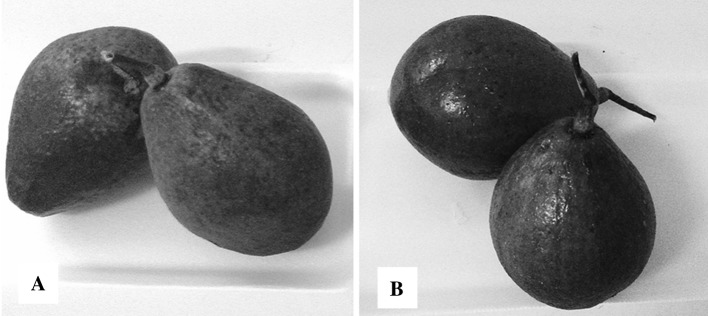

The coating adhered well to the avocado surface, conferring a brighter appearance to the epicarp throughout the whole trial period (Fig. 2). As from the twelfth storage day, the non-coated avocados presented dark spots on the skin, which are deemed undesirable for commercialization. The coated fruit presented an adequate appearance for at least eight more days as compared to the non-coated fruit, but the trial was stopped after 20 days, where after the coated fruit still showed no signs of skin darkening.

Fig. 2.

Storage trial with avocado (Persea americana Mill.) ‘Quintal’ cultivar; control avocado (no coating) (a); coated avocado (b), both after 20 days of refrigerated storage

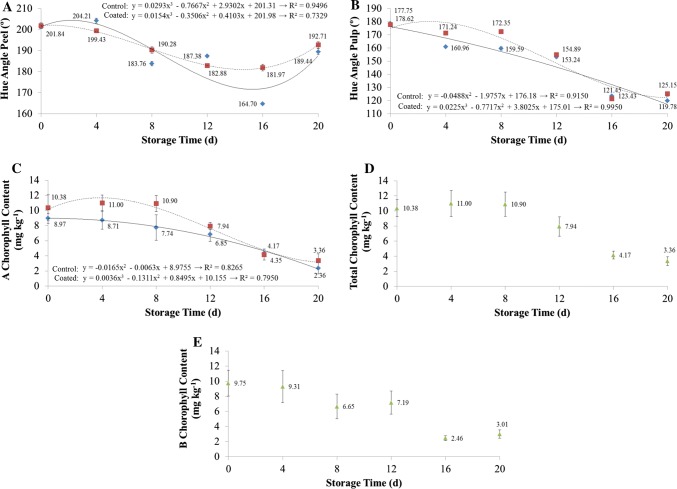

The trend of decreasing h° (peel and pulp) and chlorophylls of the avocados were observed over the whole storage period (Fig. 3). The coating promoted higher h° on the peel at the sixteenth and twentieth days (Fig. 3a) and on the pulp at the fourth, eighth and twentieth days (Fig. 3b). A hue angle of 180° is equivalent to a pure green tonality, 270° to pure blue and 90° to pure yellow. During refrigerated storage, the peel tonality of the coated fruit changed from slightly bluish green to pure green, whereas that of the control fruit changed from slightly bluish green to a yellowish green.

Fig. 3.

The effect of the coating and refrigerated storage time (10 ± 2 °C and 65–85% RH) on hue angle peel (a), hue angle pulp (b), A chlorophyll (c) total chlorophyll (d) and B chlorophyll content (e). Diamond: control fruit; square: coated fruit; triangle: tendency of control and coated fruit

When evaluating the chlorophyll content of the avocado pulp, it was possible to verify the reduction (p < 0.05) of the content during the storage period (Fig. 3c–e). Higher levels (p > 0.05) of chlorophyll A were noted on coated fruit compared to non-coated fruit (Fig. 3c), although no effect (p < 0.05) of coating has been noted on the fruit in regard to total and B chlorophyll (Fig. 3d, e) both having a significant reduction over the storage time (p < 0.05). The pulp of coated avocado was greener than that of non-coated fruit; these changes in color may be associated with chlorophyll degradation and unmasking of the skin carotenoids, natural to fruit ripening (Paliyath et al. 2008). The coating offered longer shelf life to avocados with preservation of the green color, both in the peel and in the pulp. This can be explained by the fact that the coating acts as a gas barrier, reducing the respiratory rate and, consequently, the metabolism of the fruit. Due to the respiratory process of the fruit, some coatings with gas barrier properties can cause a passive modified atmosphere, with an increase in CO2 and reduction in O2, thus, contributing to a reduction in chlorophyll degradation (Costa et al. 2011).

Chlorophyll degradation is an important catabolic process for the ripening of green fruit (Bonora et al. 2000) and the chlorophyllase acts by removing a phytol group, producing chlorophyllidium, the first degradation product. This is followed by the removal of the central Mg ion by Mg-dequelatase and the pheoforbidium is oxidized by the pheophorbide oxygenase. This gives rise to a primary fluorescent chlorophyll catabolic product, which is converted into non-fluorescent chlorophyll catabolites, thereby unmasking the carotenoids (Thomas et al. 2002).

Avocado is a tropical fruit sensible to chilling, a physiological disorder related to storage at low temperatures. The main chilling symptom in avocado is the darkening of the pulp. Since L* and C* values did not change over the storage period it suggested that the temperature at 10 °C was proper to keep the quality of avocado, without any chilling symptons. The safety temperature to store avocados is generally between 7 and 10 °C (Yahia and Woolf 2011).

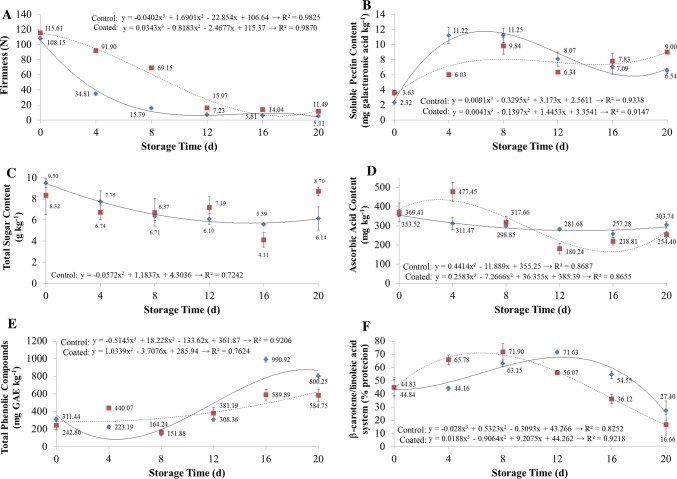

The firmness of the avocados reduced significantly (p < 0.05) during refrigerated storage for both treatments, although the firmness of the coated fruit was greater than that of the control fruit during all storage periods (Fig. 4a). The non-coated fruits lost more than half of their initial firmness in the first 4 days of refrigerated storage, whereas the same loss took approximately 12 days in the coated fruits. An increase in soluble pectin was observed up to 7 days of storage for non-coated avocados and until the last day of storage for coated avocados (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

The effect of the coating and refrigerated storage time (10 ± 2 °C and 65–85% RH) on firmness (a), soluble pectin content (b), total sugar content (c), ascorbic acid (d), total phenolic compounds (e) and % protection of the β-carotene/linoleic acid system (f). Diamond: control fruit; square: coated fruit

Besbes et al. (2011), studying the strengthening potential of nanofibrilated eucalyptus and pine celluloses in a polymeric matrix, showed that their incorporation conferred a dense and cohesive structure, improving the water vapor barrier property of the coating. This characteristic could reflect directly on the firmness of the coated fruit, since the mass loss, mainly that from water vapor, made the fruit less turgid and, consequently, less firm, which was observed in the present study, in which rice skin nanofibers were added to the coating.

During ripening of the fruit, depolymerization or shortening of the chain length of the pectic substances occurs due to the action of pectinases (Payasi et al. 2009), leading to pectic solubilization and softening of fruit. In fact, that increase in soluble pectin may be associated to the reduction in firmness of the fruit. Soluble pectin reduction in non-coated fruits after 7 days may be explained by its possible utilization as respiratory substrate. On the other hand, the coated fruits did not show this reduction, suggesting they were a long way from senescence and fresher than the non-coated ones. The coating, again, proved to be effective to keep the quality of avocados, by preventing softening of pectic substances.

Coatings also modify the atmosphere around fruit and contribute to a reduction in the metabolism and enzyme activity, including pectinases, which, consequently, slow ripening of the fruit during storage and its softening (Payasi et al. 2009). A reduction in firmness of coated plums during storage was also reported by Martínez-Romero et al. (2017).

The level of total sugars decreased from day zero to day sixteen during storage (Fig. 4c). Although the variable total sugars had been affected by the interaction between coating and storage, it was not possible to adjust any mathematical model. In the control fruits, it is possible to see the trend of reduction of the sugar content from day zero to day twenty.

Ascorbic acid content showed a fluctuation pattern, tending to decrease, on both coated and non-coated fruit, over the 20 day period. Del Aguila et al. (2006) reported that ascorbic acid content is affected by biosynthesis as well as degradation reactions. Ascorbic acid of many vegetables tends to be reduced during ripening and storage period. This often occurs due to the action of ascorbic acid oxidase or oxidizing enzymes such as peroxidase (Chitarra and Chitarra 2005). Other factors, for example storage temperature, application and coatings can promote stress on the fruit and thus influence its degradation (Lee and Kader 2000).

Ramful et al. (2011) classify fruit into three categories according to the ascorbic acid content: low (< 300 mg kg−1), medium (300–500 mg kg−1), and high (> 500 mg kg−1). According to this classification, avocados are classified as fruits with low ascorbic acid content, containing mainly liposoluble vitamins in their composition.

Total phenolic compound content increased during storage for both treatments, but only on the sixteenth day there was a significant difference (p < 0.05), when the control fruits showed higher levels than the coated ones (Fig. 4e).

The behavior of total phenolic compounds was inversely to that observed for ascorbic acid (Fig. 4e, d). The application of edible cover in tropical fruits can maintain or increase the content of phenolic compounds, promoting the increase in antioxidant capacity of the fruit. The accumulation of phenolic compounds can be explained by the activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase that is activated under stress conditions, refrigerated storage, inducing a greater synthesis of phenolic compounds (Simões et al. 2009; Gonzalez-Aguilar et al. 2010).

Marathe et al. (2011) classify fruits into three categories according to the phenolic compounds content: low (< 1000 mg kg−1), medium (1000–2000 mg kg−1), and high (> 2000 mg kg−1). Based on their classification system and the results of the present study, avocados are classified as fruits with low phenolic content. These results are in accordance with the findings of Wang et al. (2010) for avocado fruits.

The antioxidant activity of the coated fruits were higher than the control fruit until the eighth day, but lower on the twelfth, sixteenth and twentieth days (Fig. 4f).

Daiuto et al. (2014) evaluated the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of ‘Hass’ avocados, and reported lower total phenolic compounds values, as observed in the present study. These differences could be explained by the environmental characteristics of the cultivation, the specific cultivar used, the ripeness state of the fruit, the extraction methodologies used, and also the storage conditions, which probably contribute to the synthesis of phenolic compounds (Vizzotto et al. 2012).

The β-carotene/linoleic acid method is based on the oxidation of the β-carotene, induced by the oxidative degradation of linoleic acid (Rufino et al. 2007). The values obtained for antioxidant activity by this method varies as a function of time. Avocado fruits antioxidant activity evaluated oscillated during storage, a trend of decrease in the antioxidant activity over the storage period, without a systematic effect of coating. The antioxidant activity of coated fruit was higher at the eighth day, but lower on day sixteenth. Avocados have natural antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid, phenolics, tocopherol and carotenoid, that may contribute to the total antioxidant capacity of the fruit (Calderón-Oliver et al. 2016). In this study, the behavior of antioxidant activity may be associated with the ascorbic acid behavior.

Potassium sorbate was incorporated into the coating formulation in order to avoid microbial growth. It has a fungistatic effect due to inhibition of the dehydrogenase enzyme system, by altering the electrochemical potential and hence, altering the amino acid cycle and consequently, that of the enzymes (Baldino et al. 2016). Both coated and non-coated fruits did not present contamination. So, the good manufacturing practices applied were satisfactory to preserve the microbiological safety of the fruit, in spite of the use of potassium sorbate.

Although the work has been carried out with the ‘Quintal’ cultivar, it can serve as a basis for other cultivars, because they behave similarly when these active coatings are applied.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the possibility to prolong ‘Quintal’ avocado shelf life when using a coating of broken rice grain flour, rice skin cellulosic nanofibers, citrus pectin, sorbitol and potassium sorbate. This resulted in maturation delay of the fruit for a minimum of 8 days. The coating promoted lower respiration rate, lower mass loss and higher firmness compared to the control fruit, throughout the storage period. The coating, in combination with good hygiene practice, contributed to the non-appearance and non-incidence of visible microbiological contamination. Finally, coating the extended the shelf-life and preserved the postharvest quality of avocado.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to CAPES for the scholarship awarded, to the Academic Cooperation Program (PROCAD Project 8881.068456/2014-01), FAPEG, FAPEMIG, and CNPq for financial support, and to the Federal Universities of Goiás and Lavras for their scientific support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ítalo Careli-Gondim, Email: icg.nutricao@yahoo.com.br.

Taciene Carvalho Mesquita, Email: tacienecarvalho@hotmail.com.

Eduardo Valério de Barros Vilas Boas, Email: evbvboas@dca.ufla.br.

Márcio Caliari, Email: macaliari@ig.com.br.

Manoel Soares Soares Júnior, Email: mssoaresjr@hotmail.com.

References

- Baldino L, Cardea S, Reverchon E. Production of antimicrobial membranes loaded with potassium sorbate using a supercritical phase separation process. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2016;34:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2016.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besbes I, Vilar MR, Boufi S. Nanofibrillated cellulose from Alfa, Eucalyptus and Pine fibres: preparation, characteristics and reinforcing potential. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;86:1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter T, Muir HM. A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal Biochem. 1973;4:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(62)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonora A, Pancaldi S, Gualandri R, Fasulo MP. Carotenoid and ultrastructure variations in plastids of Arum italicum Miller fruit during maturation and ripening. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:873–884. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.346.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Oliver M, Escalona-Buendía HB, Medina-Campos ON, et al. Optimization of the antioxidant and antimicrobial response of the combined effect of nisin and avocado byproducts. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;65:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.07.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chitarra MIF, Chitarra AB. Fruit and vegetable postharvest: physiology and handling. 2. Lavras: Universidade Federal de Lavras (UFLA); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Costa C, Lucera A, Conte A, et al. Effects of passive and active modified atmosphere packaging conditions on ready-to-eat table grape. J Food Eng. 2011;102:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho MDO, Barbosa JB, Talma SV, et al. Effect of starch based coating in the preservation of avocado fruit (Persea americana) at ambient temperature. J Fruits Veg. 2015;1:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan AK, Wolstenholme BN. Avocado. In: Caballero B, Finglas PM, Toldra F, editors. Encyclopedia of food and health. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Daiuto ÉR, Tremocoldi MA, de Alencar SM, et al. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the pulp, peel and by products of avocado “Hass”. Rev Bras Frutic. 2014;36:417–424. doi: 10.1590/0100-2945-102/13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Aguila JS, Sasaki FF, Heiffig LS, et al. Fresh-cut radish using different cut types and storage temperatures. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2006;40:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2005.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dische E. Color ractions of carbohydrates. In: Whistler RL, Wolfrom ML, BeMiller JN, Shafizadeh F, editors. Methods in carbohydrate chemistry. New York: Academic Press; 1962. pp. 477–512. [Google Scholar]

- Engel VL, Poggiani F. Study of foliar chlorophyll concentration and its light absorption spectrum as related to shading at the juvenile phase of four native forest tree species. Rev Bras Fisiol Veg. 1991;3:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi M, Mousavi M, Yousefi H, Labbafi M. All-cellulose nanocomposite film made from bagasse cellulose nanofibers for food packaging application. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;104:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Aguilar GA, Villa-Rodriguez JA, Ayala-Zavala JF, et al. Improvement of the antioxidant status of tropical fruits as a secondary response to some postharvest treatments. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2010;21:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2010.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi SMB, Khaneghah AM. Characterization of novel basil-seed gum active edible films and coatings containing oregano essential oil. Prog Org Coat. 2017;110:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.04.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johar N, Ahmad I, Dufresne A. Extraction, preparation and characterization of cellulose fibres and nanocrystals from rice husk. Ind Crops Prod. 2012;37:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Ghoshal G, Goyal M. Synthesis and functional properties of gelatin/CA-starch composite film: excellent food packaging material. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56:1954–1965. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03662-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrauri JA, Rupérez P, Saura-Calixto F. Effect of drying temperature on the stability of polyphenols and antioxidant activity of red grape pomace peels. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:1390–1393. doi: 10.1021/jf960282f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Kader AA. Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2000;20:207–220. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00133-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe SA, Rajalakshmi V, Jamdar SN, Sharma A. Comparative study on antioxidant activity of different varieties of commonly consumed legumes in India. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2005–2012. doi: 10.1016/J.FCT.2011.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Romero D, Zapata PJ, Guillén F, et al. The addition of rosehip oil to Aloe gels improves their properties as postharvest coatings for maintaining quality in plum. Food Chem. 2017;217:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCready PM, McComb EA. Extraction and determination of total pectic material. Anal Chem. 1952;24:1586–1588. doi: 10.1021/ac60072a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka A, Maruo T, Ishibashi C, et al. Expression of genes encoding xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase in ‘Saijo’ persimmon fruit during softening after deastringency treatment. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2011;62:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AR, Ribeiro AEC, Oliveira ÉR, et al. Broken rice grains pregelatinized flours incorporated with lyophilized açaí pulp and the effect of extrusion on their physicochemical properties. J Food Sci Technol. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03606-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paliyath G, Murr DP, Handa AK, Lurie S. Postharvest biology and technology of fruits, vegetables, and flowers. New York: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Payasi A, Mishra NN, Chaves ALS, Singh R. Biochemistry of fruit softening: an overview. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2009;15:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s12298-009-0012-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramful D, Tarnus E, Aruoma OI, et al. Polyphenol composition, vitamin C content and antioxidant capacity of Mauritian citrus fruit pulps. Food Res Int. 2011;44:2088–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.03.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rufino MSM, Alves RE, de Brito ES, et al. Scientific methodology: determination of total antioxidant activity in fruits by capture of free radical DPPH. Ministério da Agric Pecuária e Abast. 2007;23:1–4. doi: 10.1017/cbo9781107415324.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer B, Wolstenholme BN, Whiley AW. The avocado: botany, production and uses. 2. Jackson: Homestead; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silva FOR, Ramos JD, Oliveira MC, et al. Reproductive phenology and physicochemical characterization of avocado varieties in Carmo da Cachoeira, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rev Ceres. 2014;61:105–111. doi: 10.1590/S0034-737X2014000100014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simões ADN, Tudela JA, Allende A, et al. Edible coatings containing chitosan and moderate modified atmospheres maintain quality and enhance phytochemicals of carrot sticks. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2009;51:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strohecker R, Henning HM. Vitamin analysis: proven methods. Madrid: Paz Montalvo; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfay SZ, Magwaza LS. Evaluating the efficacy of moringa leaf extract, chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose as edible coatings for enhancing quality and extending postharvest life of avocado (Persea americana Mill.) fruit. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2017;11:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.fpsl.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H, Ougham H, Canter P, Donnison I. What stay-green mutants tell us about nitrogen remobilization in leaf senescence. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:801–808. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.370.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzotto M, Raseira MCB, Pereira MC, Fetter MR. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of different Genotypes of blackberry (Rubus sp.) Rev Bras Frutic. 2012;34:853–858. doi: 10.1590/S0100-29452012000300027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Bostic TR, Gu L. Antioxidant capacities, procyanidins and pigments in avocados of different strains and cultivars. Food Chem. 2010;122:1193–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watada A, Abe K, Yamuchi N. Physiological activities of partially processed fruits and vegetables. Food Technol. 1990;44:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse AL. Polyphenolics: Determination of total phenolics. In: Wrolstad RE, editor. Current protocols in food analytical chemistry. New York: Wiley; 2002. pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yahia EM, Woolf AB. Avocado (Persea americana Mill.) In: Yahia EM, editor. Postharvest biology and technology of tropical and subtropical fruits. Volume 2: Açai to citrus. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2011. pp. 125–185. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.