Ragweed is a plant from the Asteraceae family and a major source of pollen allergens in late summer and autumn, especially in the US and Central and Southern Europe. In the US, most Ambrosia species are native, with a prevalence of ~45% in atopic individuals. Sensitization is spreading in Europe where Ambrosia artemisiifolia (short ragweed) was imported through Hungary at the beginning of the last century.1 Let us imagine a ragweed-allergic man living in Europe, who is sensitized only to short ragweed, and moves to the US where he becomes newly exposed to proteins from other ragweed species. Few questions arise related to his immune response: 1) Would he react to allergens from the species to which he is newly exposed in America (i.e. A. trifida, A. psilostachya)? 2) Would he develop new IgE sensitizations and T cell responses to ragweed allergens? 3) What would be the best ragweed extracts or allergen components for diagnosis and/or treatment? An analysis of the adaptive immune response at two different levels, B and T cell reactivity, will provide insights to address these questions.

IgE reactivity to ragweed allergens to which the individual is newly exposed in America is dependent on B cell (antibody) cross-reactivity, before any new and independent sensitization occurs. IgE cross-reactivity is observed when antibodies recognize proteins homologous to the sensitizing allergen. This phenomenon has been reported for pollen and food proteins, and for allergens from either closely related or the same species (isoallergens/variants). Due to its polyclonal nature, allergen-specific IgE comprises multiple antibodies recognizing different epitopes. Although antibody cross-reactivity is usually associated with high amino acid identities (>70 %) among the recognized allergens, it is determined by homology at the level of the epitope.2 Not all the antibodies involved in an IgE cross-reactive polyclonal response will necessarily cross-react. For example, an expected lack of significant cross-reactivity was found among glutathione S-transferases from cockroach, mite and Ascaris, in agreement with the low amino acid identity among these allergens (23–37%).3 However, limited antibody cross-reactivity was observed between Amb a 1.01 and Amb a 1.03, despite sharing high amino acid identity (~75%), presumably due to epitope differences between both isoallergens.4

Human T cell responses to allergens, especially T cell cross-reactivity, have been less studied. In this journal issue, Würtzen et al. report a systematic and thorough analysis of the T cell cross-reactivity of ragweed across related weed species.5 The authors analyzed in detail the T cell reactivity to full proteins and overlapping peptides from most ragweed allergens, including the major allergen Amb a 1 and other less prevalent allergens from groups 3, 4, 5, 8 and 11 (from 12 groups listed in the official Allergen Nomenclature database – www.allergen.org –). Ragweed-specific T cells strongly cross-reacted with epitopes of related ragweed species (Amb a; Amb p; Amb t) and exhibited partial cross-reactivity to the more distant species mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) (for Amb a 8). A lack of association between Amb a-specific IgE levels and the number of allergen T cell epitopes and T cell responses was observed, indicating that there is not always a correlation between B and T cell reactivity to allergens. This observation has also been reported for other allergen sources.6,7

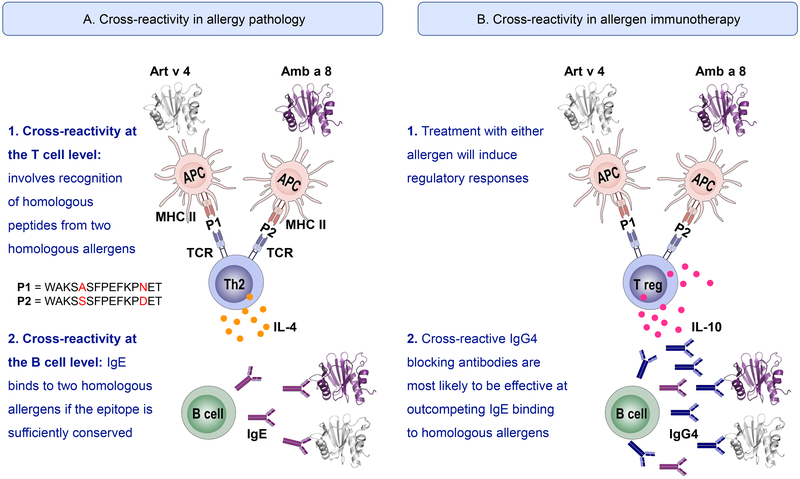

In contrast to B cell reactivity, which determines the induction of the immediate allergic inflammatory reaction during exposure or allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), T cell reactivity contributes to the late phase response, which involves recruitment and activation of eosinophils, basophils and Th2 cells. T cells are also relevant for the development of the adaptive immune response to allergens (sensitization) and for immune-modulation induced by AIT. During allergic sensitization, antigen presenting cells (APC) digest allergens into peptides that are presented in the context of MHC class II molecules to T cells for their activation (with simultaneous co-stimulation) (Figure 1). T cell cross-reactivity is observed when peptides from different allergens share key residues, allowing them to be recognized by the same T cell. Activated T cells produce cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13) that induce B cell class switching to IgE and production of allergen-specific IgE. In contrast to antibody binding, the recognition of T cell epitopes is known to be degenerate to some extent, which could contribute to a less specific T cell cross-reactivity.8 Nevertheless, T cell reactivity to new epitopes on allergens from US ragweed species would be expected.

Foot of Figure 1:

Schematic representation of mechanisms of cross-reactivity at the T (1) and B (2) cell level in allergy pathology (A) and allergen-specific immunotherapy (B). The two allergens images were created using the Protein Data Bank files of the X-ray crystal structures of two profilins: mugwort allergen Art v 4 (5EM0) and ragweed allergen Amb a 8 (5EM1), and the software PyMol. Molecules involved in APC-T cell interactions are indicated in A only: MHC II: major histocompatibility complex II; Peptides 1 and 2 (= P1 and P2): examples of possible peptides presented by the MHC II in the APC to the T cell; TCR: T cell receptor.

Cross-reactive T cells may be associated with disease pathology by reacting to allergens that the individual is not originally sensitized against and creating a cytokine milieu that leads to additional new sensitizations (Figure 1A). However, as a double-edged sword, this cross-reactivity can also be leveraged for AIT applications (Figure 1B). For example, in the study by Würtzen et al., similar T-cell responses in American and European donors were observed.5 Therefore, similar ragweed extracts might be effective in inducing tolerance in American and European populations. Even more striking is the fact that not all allergens from the same source are created equal, meaning that some allergens are more dominant than others. Dominance may refer to a larger IgE prevalence and/or to a larger percentage of allergen-specific IgE reactivity. It might be determined by factors such as different patterns of allergen exposure depending on geographic location, intrinsic properties of the allergen that affect allergenicity or genetic factors. Amb a 1, originally named antigen E, is the most important ragweed allergen, to which more than 95% of ragweed allergic individuals are sensitized.1 This allergen includes the original Amb a 2 (antigen K), which was renamed as Amb a 1.05 given the high sequence identity (61–70%) with the remaining Amb a 1 isoallergens. The 5 isoallergens were present in extracts used in the study.5 The clinical relevance of Amb a 1 was highlighted in a 4-year immunotherapy study by Norman et al. in 1968. Purified Amb a 1 was as effective as the whole ragweed extract in reducing allergic symptoms of ragweed-induced hayfever.9 Therefore, the immunodominance of this allergen might make it sufficient for AIT, regardless of sensitization to other minor allergens, in addition to covering for vaccination against homologous cross-reactive allergens.

Acknowledgements:

Research in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI077653 (to AP) and U19 AI135731. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wopfner N, Gadermaier G, Egger M, et al. The spectrum of allergens in ragweed and mugwort pollen. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;138:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glesner J, Vailes LD, Schlachter C, et al. Antigenic determinants of Der p 1: specificity and cross-reactivity associated with IgE antibody recognition. J Immunol. 2017;198:1334–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller GA, Pedersen LC, Glesner J, et al. Analysis of glutathione S-transferase allergen cross-reactivity in a North American population: Relevance for molecular diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1369–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf M, Twaroch TE, Huber S, et al. Amb a 1 isoforms: Unequal siblings with distinct immunological features. Allergy. 2017;72:1874–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Würtzen P, Hoof I, Christensen L, et al. Diverse and highly cross-reactive T cell responses in ragweed allergic patients independent of geographical region. Allergy. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oseroff C, Sidney J, Kotturi MF, et al. Molecular determinants of T cell epitope recognition to the common Timothy grass allergen. J Immunol. 2010;185:943–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oseroff C, Sidney J, Tripple V, et al. Analysis of T cell responses to the major allergens from German cockroach: Epitope specificity and relationship to IgE production. J Immunol. 2012;189:679–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazza C, Auphan-Anezin N, Gregoire C, et al. How much can a T-cell antigen receptor adapt to structurally distinct antigenic peptides? EMBO J. 2007;26:1972–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norman PS, Winkenwerder WL, Lichtenstein LM. Immunotherapy of hay fever with ragweed antigen E: comparisons with whole pollen extract and placebos. J Allergy. 1968;42:93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]