Abstract

It is well-established that complexes of plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) with its target enzymes bind tightly to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), but the molecular details of this interaction are not well-defined. Furthermore, considerable controversy exists in the literature regarding the nature of the interaction of free PAI-1 with LRP1. In this study, we examined the binding of free PAI-1 and complexes of PAI-1 with low-molecular-weight urokinase-type plasminogen activator to LRP1. Our results confirmed that uPA:PAI-1 complexes bind LRP1 with ∼100-fold increased affinity over PAI-1 alone. Chemical modification of PAI-1 confirmed an essential requirement of lysine residues in PAI-1 for the interactions of both PAI-1 and uPA:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1. Results of surface plasmon resonance measurements supported a bivalent binding model in which multiple sites on PAI-1 and uPA:PAI-1 complexes interact with complementary sites on LRP1. An ionic-strength dependence of binding suggested the critical involvement of two charged residues for the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1 and three charged residues for the interaction of uPA:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1. An enhanced affinity resulting from the interaction of three regions of the uPA:PAI-1 complex with LDLa repeats on LRP1 provided an explanation for the increased affinity of uPA:PAI-1 complexes for LRP1. Mutational analysis revealed an overlap between LRP1 binding and binding of a small-molecule inhibitor of PAI-1, CDE-096, confirming an important role for Lys-207 in the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1 and of the orientations of Lys-207, -88, and -80 for the interaction of uPA:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1.

Keywords: lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), site-directed mutagenesis, serpin, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), fibrinolysis, ligand recognition, LRP1, PAI-1, plasminogen activation

Introduction

The activity of the two plasminogen activators, urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)3 and tissue-type plasminogen activator, is regulated by plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), a serine proteinase inhibitor (serpin) that regulates fibrinolysis and wound healing, and is associated with thrombotic and fibrotic disease (1, 2). Serpins function to inhibit serine proteases by a unique mechanism following cleavage of the serpin's reactive center loop that induces a conformational change in the serpin resulting in protease inhibition (3). Once a serpin complexes with a protease, the complex is rapidly removed from the circulation in the liver by binding to the LDL receptor–related protein 1 (LRP1) (4).

LRP1 was originally identified as the hepatic receptor responsible for the removal of α2-macroglobulin (α2M) protease complexes (5, 6) and as a receptor for chylomicron remnant lipoprotein particles (7). In addition to its endocytic role, LRP1 also regulates various signaling pathways (8, 9). The ectodomain of this large receptor is made up of modules that consist of clusters of LDLa repeats, epidermal growth factor–like repeats, and β-propeller domains. The efficient delivery of newly-synthesized LRP1 to the cell surface requires the participation of an endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone, termed the receptor-associated protein (RAP) (10–12).

The fact that LRP1 recognizes numerous structurally unrelated ligands with relatively high affinity has raised questions regarding the nature of ligand/receptor interaction. Insight into how this might occur resulted from recognition that Lys-256 and Lys-270 are essential for the third domain of RAP to bind LRP1 (13) and from a crystal structure of the third domain of RAP in complex with two LDLa repeats from the LDL receptor (14). These studies revealed that the ϵ-amino groups of Lys-256 and Lys-270 on RAP form salt bridges with carboxylates of aspartate residues within the LDLa repeats that form an acidic pocket on the receptor. To date, several ligands, including activated forms of α2M (15) and blood coagulation factor VIII (16, 17), have been shown to interact with LRP1 via interactions involving critical lysine residues.

Although lysine residues appear to contribute to the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1 (18–20), studies investigating the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1 have resulted in conflicting data. First, questions exist regarding the relative affinity of PAI-1 versus protease:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1. Most studies have demonstrated that only PAI-1 in complex with a protease binds to LRP1 with high affinity (18, 21–23). In contrast, other studies (20, 24) have reported that PAI-1 alone binds with high affinity to fragments derived from LRP1. Second, based on the observation that protease:PAI-1 complexes bind with higher affinity to LRP1 than PAI-1 alone, some have proposed that formation of a protease complex with PAI-1 exposes a cryptic epitope on PAI-1 that is recognized by LRP1 (18, 21). In contrast, others have argued that the protease itself might interact with LRP1 and contribute to the high-affinity interaction (25). Finally, although a number of studies have reported changes in the affinity of PAI-1 for LRP1 when various basic residues are mutated to alanine (18, 19, 21, 25), there seems to be little consensus on which lysine residues constitute the binding site.

The objectives of this study were to first clarify the relative binding affinities of PAI-1 and protease:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1 and second to determine whether the binding of a protease:PAI-1 complex to LRP1 is mainly attributed to determinants on PAI-1. A final goal was to identify specific amino acid residues in free PAI-1 and PAI-1 in complex with a target protease that participate in their binding to LRP1.

Results

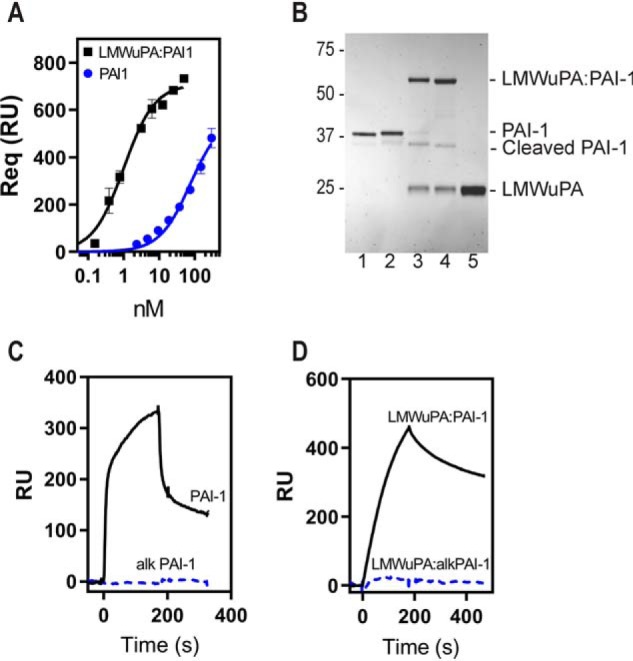

LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes bind to LRP1 with higher affinity than PAI-1 alone

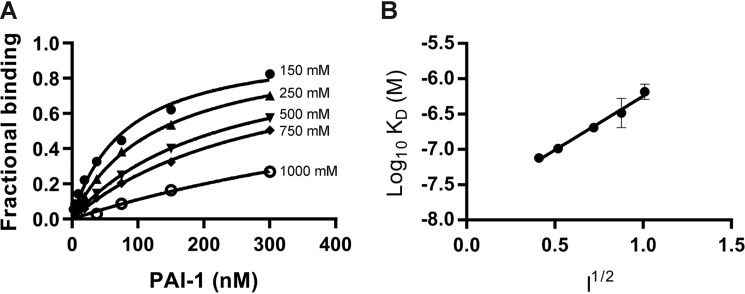

To resolve the conflict that exists in the literature regarding the relative affinities of PAI-1 and protease:PAI-1 complexes for LRP1, our initial experiment compared the binding of free PAI-1 and PAI-1 complexed to LMWuPA to LRP1. Notably, LMWuPA itself does not bind to LRP1 (data not shown). Since WT PAI-1 is relatively unstable and rapidly converts to the latent form, experiments in this and all subsequent studies (unless designated otherwise) used the I91L mutant of PAI-1 that extends the stability of PAI-1 from a half-life of 2.0 to 18.4 h (27). Experiments (see below) confirm that I91L PAI-1, either free or in complex with uPA, is nearly identical to WT PAI-1 in its ability to bind LRP1. We formed a complex of I91L PAI-1 with LMWuPA and compared its binding with that of free PAI-1 to LRP1 using equilibrium SPR measurements. The data (Fig. 1A) reveal that the LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex binds almost 2 orders of magnitude tighter to LRP1 than PAI-1 alone (KD for LMWuPA:PAI-1 = 0.9 ± 0.2 nm, and the KD for PAI-1 = 74 ± 13 nm).

Figure 1.

Essential role for lysine residues on PAI-1 for the binding of PAI-1 and LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1. A, binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex and free PAI-1 to LRP1 analyzed by SPR in which Req values were determined by equilibrium measurements. Three independent experiments were performed, and the means ± S.E. are plotted. KD values (0.9 ± 0.2 nm for LMWuPA:PAI-1 and 74 ± 13 nm for PAI-1) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis. B, PAI-1 (lane 1) and chemically modified PAI-1 (lane 2) form complexes with LMWuPA (lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Lane 5, LMWuPA. C, 250 nm PAI-1 and 300 nm PAI-1 chemically modified with sulfo-NHS-acetate were injected over an SPR chip to which LRP1 was immobilized. D, 9 nm LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex and 80 nm complex formed with chemically modified PAI-1 were injected over an SPR chip to which LRP1 was immobilized. RU, response unit.

Lysine residues on PAI-1 are essential for binding of both PAI-1 and LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1

To determine the contribution of lysine residues to the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1, we chemically modified these residues with sulfo-NHS-acetate, which forms stable, covalent amide bonds with primary amines of lysine residues. This modification does not prevent PAI-1 from forming a stable complex with LMWuPA (Fig. 1B). Remarkably, however, this modification prevented the binding of both free PAI-1 (Fig. 1C) and the complex of LMWuPA with modified PAI-1 from binding to LRP1 (Fig. 1D). These results reveal that lysine residues on PAI-1 contribute to the binding of both PAI-1 and the LMWuPA:PA1–1 complex to LRP1.

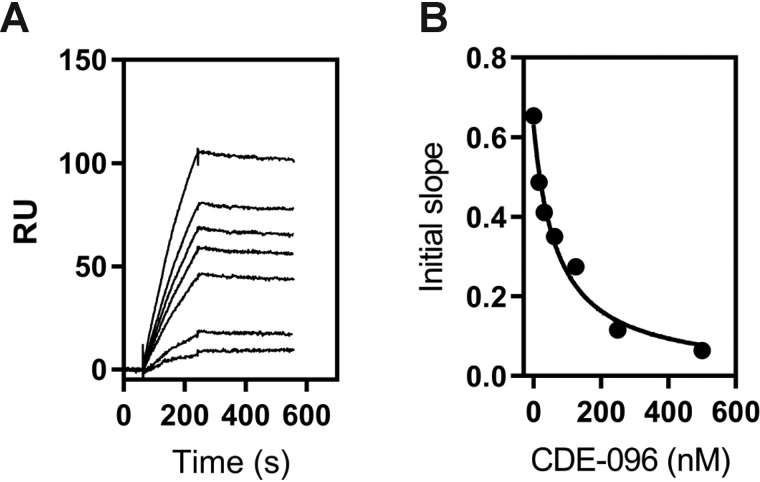

Two charged residues are involved in the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1

We next examined the effect of ionic strength on the binding of wildtype (WT) PAI-1 to LRP1. The results of these experiments reveal that the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1 depends upon ionic strength (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B shows the data plotted in the form of a Debye-Hückel plot, where the log10 KD value is plotted versus ionic strength. These results suggest the involvement of two ionic interactions in the binding of PAI-1 with LRP1 as indicated by the slope (slope = 1.5 ± 0.1). This is consistent with the canonical model for the binding of ligands to the LDL receptor family members in which two (or more) ϵ-amino groups of specific lysine residues located on the ligand form salt bridges with carboxylates of aspartate residues within the LDLa repeats (14).

Figure 2.

Binding of PAI-1 to LRP1 is ionic strength–dependent. A, increasing concentrations of PAI-1 in a buffer containing increasing concentrations of NaCl were injected over LRP-1–coated SPR chips, and Req values were determined. The data are normalized to Rmax for each NaCl concentration. The concentrations of NaCl from the top curve down are as follows: 150, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 mm. B, Debye-Hückel plot of PAI-1 binding to LRP1. The KD value at each ionic strength (150, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 mm NaCl) was measured by equilibrium SPR measurements. Three independent experiments were performed, and the values plotted are means ± S.E. A slope of 1.5 ± 0.1 was determined by linear regression analysis. A similar value for the slope was obtained by averaging the results from linear regression analysis of individual experiments.

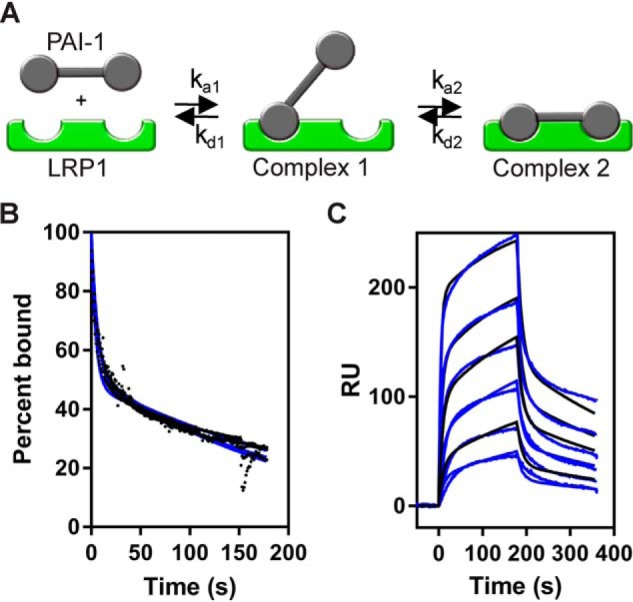

Kinetic analysis supports a bivalent model for binding of PAI-1 to LRP1

The data from Fig. 2 suggest the involvement of at least two charged residues in the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1, raising the possibility of a bivalent binding model in which high-affinity binding results from avidity effects mediated by interaction of two regions on PAI-1, each containing charged residues, with two LDLa repeats on LRP1 (Fig. 3A). A similar model has been proposed for the binding of FVIII to LRP1 (17). To test this model, we performed kinetic measurements examining the binding of I91L PAI-1 to LRP1 using surface plasmon resonance experiments. To gain insight into potential mechanisms, we initially compared the kinetics of PAI-1 dissociation from LRP1 at various concentrations of ligand (Fig. 3B). These results reveal that dissociation kinetics occurs in two phases: a fast phase followed by a much slower phase. In addition, as expected for a bivalent model, the dissociation kinetics is independent of ligand concentration. The dissociation rate constants determined from a fit of the experimental data were used as initial estimates for the dissociation phase when the association and dissociation kinetics were simultaneously fit to a global bivalent model. This fit revealed that the experimental data are well-described by a bivalent binding model (Fig. 3C). The kinetic data from the best fit (Table 1) reveal a rapid association of PAI-1 with LRP1 to form Complex I and a conversion to Complex II with a half-life of 97 s. Importantly, the value for the equilibrium binding constant, KD, derived from kinetic analysis (65 ± 6 nm) is close to the KD value of 56 ± 4 nm determined by equilibrium analysis of the SPR data. To determine whether any difference occurs between the binding of I91L PAI-1 and WT PAI-1 to LRP1, we also investigated the detailed binding kinetics for WT PAI-1 with LRP1. The kinetic and equilibrium binding data are summarized in Table 1 and reveal kinetic constants and KD values for WT PAI-1 that are similar to those for the I91L stable mutant.

Figure 3.

Binding of PAI-1 to LRP1 is well-described by a bivalent binding model. A, schematic of a bivalent binding model for the interaction of two distinct regions on PAI-1 with complementary sites on LRP1. B, increasing concentrations of PAI-1 (9.4, 37.5, 75, and 300 nm) were injected over the LRP1-coupled SPR chip. The dissociation of each concentration was measured from the SPR data, with the initial value at t = 0 normalized to 100%. Data were fit to a two-exponential decay (blue line). C, increasing concentrations of PAI-1 (3.9, 7.8, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5, and 125 nm) were injected over the LRP1-coupled chip. Fits of the experimental data (black lines) to a bivalent binding model are shown as blue lines. The data show a representative experiment from six independent experiments that were performed. RU, response unit.

Table 1.

Kinetic and equilibrium constants for the binding to WT PAI-1 and I91L PAI-1 to LRP1

Kinetic constants were obtained by fitting the data to a bivalent model (Scheme 1).

| Ligand/receptor | ka1 | kd1 | ka2 | kd2 | KDa | KDb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/ms | 1/s | 1/s | 1/s | nm | nm | |

| I91L PAI-1/LRP1c | 7.1 ± 0.4 × 105 | 0.152 ± 0.007 | 7.1 ± 0.2 × 10−3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 × 10−3 | 65 ± 6 | 56 ± 4 |

| WT PAI-1/LRP1d | 5.6 ± 0.7 × 105 | 0.120 ± 0.004 | 1.1 ± 0.7 × 10−2 | 5.1 ± 0.3 × 10−3 | 69 ± 3 | 85 ± 16 |

| 14–1B PAI-1/LRP1d | 3.9 ± 0.5 × 105 | 0.157 ± 0.017 | 5.3 ± 0.7 × 10−3 | 4.2 ± 0.2 × 10−3 | 194 ± 10 | 233 ± 14 |

| I91L PAI-1/Cluster IVc | 5.1 ± 0.4 × 105 | 0.097 ± 0.007 | 3.1 ± 0.2 × 10−3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 × 10−3 | 55 ± 5 | 49 ± 18 |

a The equilibrium binding constant KA was calculated using the following equation: KA = (ka1/kd1)·(1 + (ka2/kd2)), and KD was calculated as: KD = 1/KA.

b Data were calculated from equilibrium SPR measurements, in which Req was determined by the fitting the association data to a pseudo-first-order process.

c Six independent experiments were performed, and the values shown are the average ± S.E.

d Three independent experiments were performed, and the values shown are the average ± S.E.

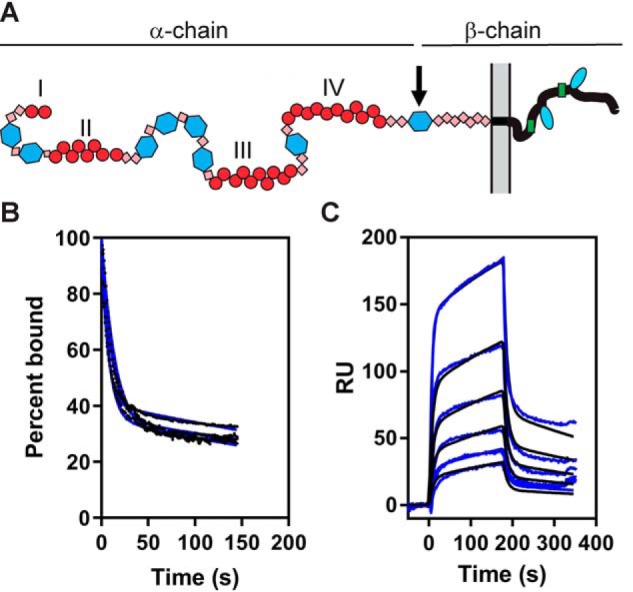

The ligand binding regions of LRP1 are mainly localized to clusters of LDLa repeats, termed clusters I–IV (Fig. 4A). Of these clusters, most ligands bind to clusters II, III, or IV. Thus, we also examined the binding of PAI-1 to clusters II–IV. Initial experiments revealed that I91L PAI-1 interacted with similar affinities to clusters II and IV, but with a much weaker affinity to cluster III. We then conducted detailed experiments employing cluster IV, which is a major ligand-binding region of LRP1. Fig. 4B confirms that the dissociation of PAI-1 from cluster IV also occurs with two phases and is independent of PAI-1 concentration. A comparison of the fit to experimental data reveal that the binding is consistent with a bivalent binding model (Fig. 4C). The best-fit parameters are summarized in Table 1, which reveal a KD value of 55 ± 5 nm derived from the kinetic data that is close to the KD value of 49 ± 18 nm estimated by equilibrium analysis of the SPR data. Thus, these results reveal that the binding of I91L PAI-1 to cluster IV is similar to its binding to full-length LRP1.

Figure 4.

Binding of PAI-1 to cluster IV from LRP1 fits well to a bivalent binding model. A, schematic showing domain organization of LRP1. Clusters of ligand-binding repeats (red circles) are labeled I, II, III, and IV. B, increasing concentrations of PAI-1 (9.4, 15.6, 31, 62.5, and 125 nm) were injected over the LRP1 cluster IV–coupled SPR chip. The dissociation of each concentration was measured from the SPR data, with the initial value at t = 0 normalized to 100%. Data were fit to a two-exponential decay (blue line). C, increasing concentrations of PAI-1 (3.9, 7.8, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5, and 125 nm) were injected over the LRP1 cluster IV–coupled chip. Fits of the experimental data (black lines) to a bivalent binding model are shown as blue lines. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments that were performed. RU, response unit.

Critical role for Lys-207 in the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1

Because chemical modification of PAI-1 revealed a critical role for lysine residues in the interaction with LRP1, we initiated studies to identify specific lysine residues that contribute to the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1. To gain additional insight into regions on PAI-1 that may be important for its interaction with LRP1, we examined the potential of CDE-096 to block the binding of HMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1. CDE-096 is a small molecule inhibitor that binds reversibly to PAI-1 and inhibits the interaction of PAI-1 with proteases via an allosteric mechanism (28). CDE-096 also binds to uPA:PAI-1 complexes (28). When CDE-096 was added to HMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes, we observed a dose-dependent inhibition of HMWuPA:PAI-1 binding to LRP1 (Fig. 5A). An IC50 of 70 ± 11 nm was determined by re-plotting the initial slope of the association curve versus CDE-096 concentration (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

CDE-096 inhibits the binding of HMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1. A, 1 nm HMWuPA:PAI-1 complex was flowed over an LRP1-coupled SPR chip in the absence (top curve) and presence of increasing concentrations of CDE-096 (15.6, 31.2, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 nm). RU, response unit. B, plots of the initial slopes of the association phase from A versus CDE-096 concentration. An IC50 of 70 ± 11 nm was determined by nonlinear regression analysis. The data are representative of two independent experiments.

Structural studies reveal that Lys-207 and Lys-263 contribute to the binding of CDE-096 with PAI-1 (28). Thus, we included these mutants of PAI-1 in our analysis, along with Lys-69, Lys-80, and Lys-88 that have been previously identified as critical for the binding of PAI-1 to LDLa repeats from cluster II (20). In these studies, the KD values were determined by SPR equilibrium measurements, and the results are summarized in Table 2. The data demonstrate that mutation of Lys-207 to alanine had the largest impact on PAI-1 binding to LRP1, decreasing the affinity by 19-fold. Mutation of Lys-69, Lys-80, and Lys-88 to alanine resulted in a 7-, 7-, and 9-fold decrease in the affinity for LPR1, respectively. Interestingly, a PAI-1 molecule with mutations in both Lys-80 as well as Lys-207 or a mutant in which Lys-80, Lys-207, and Lys-88 were all converted to alanine did not substantially reduce the affinity of PAI-1 for LRP1 over that of the K207A mutant alone and resulted in a 20- and 21-fold increase in KD, respectively.

Table 2.

Equilibrium binding constants for mutant PAI-1 binding LRP1

Unless designated, all mutations were made on the I91L PAI-1 background. For each mutant, three independent experiments were performed, and the mean values are shown.

| Mutation in PAI-1 | Fractional surface ASAa | PAI-1 |

LMWuPA:PAI-1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium analysis KDb | -Fold change | Equilibrium analysis KDb | -Fold change | ||

| nm | nm | ||||

| I91L PAI-1 | 56 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| K69A | 0.95 | 388 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| R76A (on 14–1B PAI-1 background)c | 0.24 | 157 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| R76E (on 14–1B PAI-1 background)c | 0.24 | 1298 | 23 | 45 | 90 |

| R76Ad | 0.24 | 54 | 1 | 0.4 | 1.0 |

| R76Ed | 0.24 | 133 | 2 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| K80A | 0.6 | 397 | 7 | 2.9 | 6 |

| K88A | 0.61 | 508 | 9 | 0.7 | 1 |

| K122A | 0.2 | 229 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| K176A | 0.43 | 189 | 3 | 0.7 | 1 |

| K207A | 0.68 | 1076 | 19 | 0.8 | 2 |

| K263A | 0.38 | 180 | 3 | 0.7 | 1 |

| K80A/K207A | 1136 | 20 | 13 | 26 | |

| K80A/K122A/K207A | 477 | 9 | 25 | 50 | |

| K69A/K80A/K207A | 558 | 10 | NDe | ||

| K80A/K207A/K263A | 862 | 15 | 16 | 32 | |

| K80A/K88A/K207A | 1184 | 21 | 122 | 244 | |

| K80A/K176A/K207A | 1206 | 22 | 7 | 14 | |

a The fractional surface area was calculated using VADAR (Willard et al. (29)) and PDB code 1dvm.

b Data were calculated from equilibrium measurements, in which Req was determined by the fitting the association data to a pseudo-first-order process.

c Mutations were made on the 14-1B PAI-1 stable mutant background.

d Data were determined by kinetic analysis using a bivalent model (Scheme 1).

e ND is not determined.

The data in Table 2 also show the fractional surface area of the specific side chains based on the three-dimensional structure of a 14-1B mutant of PAI-1, which is a stable variant of PAI-1 that contains four mutations (N150H, K154T, Q319L, and M3541I) (27). The fractional accessible surface area of side-chain groups is the area accessible to solvent in the protein divided by the calculated accessible surface area for that residue in an extended Gly-Xaa-Gly tripeptide (29) with values close to 1 being fully accessible and values close to 0 being buried. This analysis revealed that Arg-76, Lys-122, and Lys-263, all of which have been implicated in LRP1 binding (19, 21), are all buried or partially buried in the structure and are likely unavailable for LPR1 binding.

Arg-76 in not directly involved in the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1

Prior studies have found that the R76E PAI-1 mutant is deficient in LRP1 binding (21), and consequently, Arg-76 is thought to directly interact with LRP1 (20). However, the ASA value of 0.24 for Arg-76 (Table 2) reveals that this residue is likely buried and thus is not available for direct interaction with LRP1. Thus far, most studies examining the binding of human PAI-1 R76E mutants to LRP1 have been performed on the stable 14-1B PAI-1 background. We examined the binding of R76E and R76A mutations generated on both the 14-1B and I91L PAI-1 backgrounds. The results reveal that on the 14-1B background the R76A mutant has a 3-fold weaker binding to LRP1, whereas the R76E mutant displays a 23-fold weaker binding to LRP1 (Table 2). Furthermore, the affinities of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes generated from the R76A and R76E mutants on the 14-1B PAI background to LRP1 were reduced by 12- and 90-fold, respectively (Table 2). Surprisingly, when these mutations were introduced on the I91L PAI-1 background, little impact on the ability of mutant PAI-1 to bind to LRP1 was noted. Additionally, these PAI-1 mutants had little impact on the binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1. Together, these studies confirm that Arg-76 is not directly involved in LRP1 binding, and they further indicate that the R76E mutant uniquely impacts the structure of PAI-1 on the 14-1B background, but not on the I91L background, in a manner that impacts LRP1 binding.

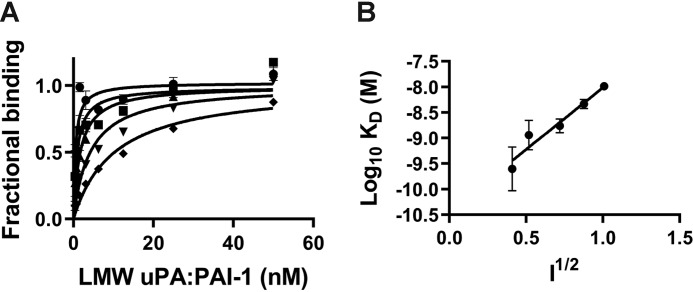

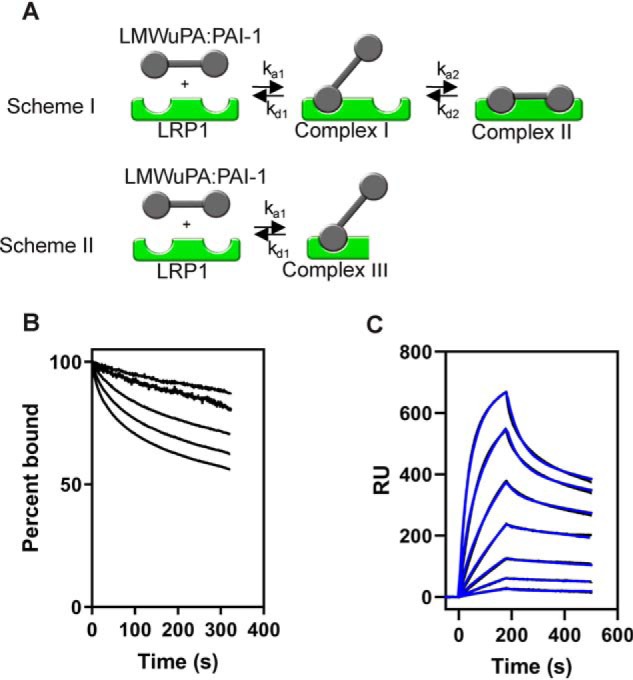

Binding LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1 occurs via complex mechanisms

To characterize the binding of LMWuPA:PA1 to LRP1, we initially examined the ionic strength dependence of the binding. The results shown in Fig. 6A demonstrate a significant dependence of binding upon the ionic strength. The Debye-Hückel plot (Fig. 6B) yields a slope of 2.4 ± 0.3 suggesting the involvement of 2–3 ionic interactions in the binding.

Figure 6.

Binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1 is ionic strength–dependent. A, increasing concentrations of uPA:PAI-1 complexes were flowed over LRP-1–coated SPR chips in the presence of increasing concentrations of NaCl, and Req values were determined. The data are normalized to Rmax for each NaCl concentration. NaCl concentrations from top curve down are as follows: 150, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 mm. B, Debye-Hückel plot of LMWuPA:PAI-1 binding to LRP1. The KD value at each ionic strength (150, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 mm NaCl) was measured by equilibrium SPR measurements. Three independent experiments were performed, and the means ± S.E. are plotted. A slope of 2.4 ± 0.4 was determined by linear regression analysis. An identical value was obtained by averaging the results from linear regression analysis of individual experiments.

When we examined the kinetics of the interaction, we observed that the dissociation kinetics changed at higher concentrations of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes (Fig. 7B). This is also apparent from the data in Fig. 7C, where a more rapid dissociation is noted at higher LMWuPA:PAI-1 concentrations, which is suggestive of multiple binding mechanisms. We have observed this before for the binding of RAP domains D1D2 to LRP1 (30). Thus, we also incorporated a second scheme into the bivalent model in which LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes are also able to bind to a second distinct site on LRP1 to form a monovalent complex (Complex III, Fig. 7A, Scheme II). To simplify the model, we assumed that the ka1 and kd1 in Scheme II is identical to ka1 and kd1 in the first step in Scheme I. When our experimental SPR data were fit to a model containing both Schemes I and II, an excellent fit was obtained (Fig. 7C), and the kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 3. The data confirm high-affinity binding of the LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex to LRP1 with a KD that is ∼100-fold lower than that of PAI-1 alone. Comparison of the kinetic constants for PAI-1 and the LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex reveals that the higher affinity is mostly attributable to a slower dissociation rate for the initial complex (Complex I, Fig. 7A) and for a more rapid conversion to Complex II (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes bind to LRP1 via a complex kinetic model. A, model used for analyzing the binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1. Scheme I, LMWuPA:PAI-1 binds via a bivalent model. At higher concentrations of LMWuPA:PAI-1, a monovalent model of binding occurs (Scheme II). B, increasing concentrations of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex (3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 nm) were injected over the LRP1-coupled chip. The dissociation of each concentration was measured from the SPR data, with the initial value at t = 0 normalized to 100%. C, increasing concentrations of LMWuPA:PAI-1 (0.78, 1.56, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25 and 50 nm) were injected over the LRP1-coupled chip. Fits of the experimental data (black lines) to a model including Schemes I and II are shown (blue lines). The data are representative of three independent experiments. RU, response unit.

Table 3.

Kinetic and equilibrium binding constants for the binding to LMWuPA:I91L PAI-1 and mutants to Cluster IV and to LRP1

Kinetic constants were obtained by fitting the data simultaneously to Schemes 2 and 3 (see Fig. 7A).

| Receptor/ligand | ka1 | kd1 | ka2 | kd2 | KD1 | KD2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/ms | 1/s | 1/s | 1/s | nm | nm | |

| LRP1/LMWuPA:I91LPAI-1a | 9.1 ± 0.4 × 105 | 1.8 ± 0.2 × 10−2 | 4.2 ± 0.9 × 10−2 | 1.8 ± 0.6 × 10−3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 3 |

| LRP1/LMWuPA:WT PAI-1a | 8.4 ± 0.5 × 105 | 2.1 ± 0.1 × 10−2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 × 10−2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 × 10−3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 2 |

| Cluster IV of LRP1a | 1.3 ± 0.5 × 106 | 4.6 ± 0.3 × 10−2 | 1.4 ± 1.3 × 10−1 | 1.0 ± 0.6 × 10−2 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 37 ± 9 |

a Three independent experiments were performed, and the values shown are the average ± S.D.

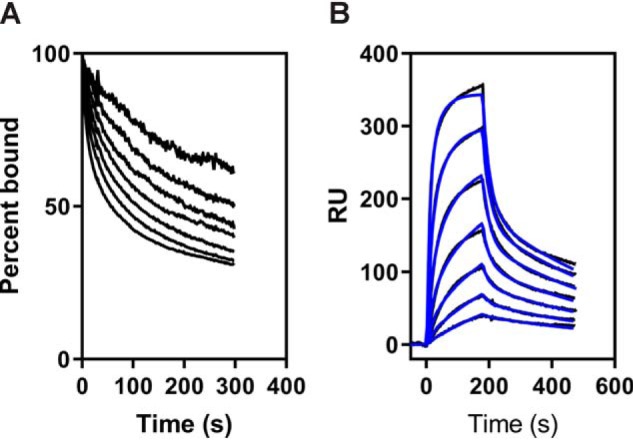

We also examined the binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to cluster IV of LRP1 immobilized on the SPR chip. Similar to the binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 to full-length LRP1, the dissociation kinetics was not independent of ligand concentration (Fig. 8A), and thus we fit the data to the model described in Fig. 7A. The data were well-described by the fit (Fig. 8B), and the parameters derived from these fits are summarized in Table 3 and reveal that LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes bind slightly weaker to cluster IV than to full-length LRP1. These results suggest that LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes may also interact with regions of LRP1 that are outside of the cluster IV region of LRP1.

Figure 8.

Kinetic analysis of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes binding to cluster IV of LRP1. A, increasing concentrations of the uPA:PAI-1 complex (0.6, 1.2, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 nm) were injected over the LRP1-coupled chip. The dissociation of each concentration was measured from the SPR data, with the initial value at t = 0 normalized to 100%. B, increasing concentrations of LMWuPA:PAI-1 (0.6, 1.2, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 nm) were injected over the LRP1-coupled chip. Fits of the experimental data (black lines) to Schemes 1 and 2 are shown as blue lines. The data are representative of three independent experiments. RU, response unit.

PAI-1 mutants reveal additional residues are involved in the interaction of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1

To determine whether similar lysine residues on PAI-1 are also involved in the interaction of uPA:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1, we also formed complexes of LMWuPA with mutant PAI-1 molecules and measured the binding of these complexes to LRP1. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 2. Interestingly, unlike the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1, individual mutants of PAI-1 (K69A, K88A, and K207A) had minimal impact on the binding of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1, although K80A resulted in a 5.8-fold decrease in KD. A PAI-1 molecule containing a double mutant of K80A and K207A resulted in a 23-fold decrease in the binding of the LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex to LRP1. Strikingly, the triple mutant of K80A, K207A, and K88A resulted in a 244-fold decrease in affinity (Table 2) revealing a critical role for these three residues in the LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex for binding to LRP1.

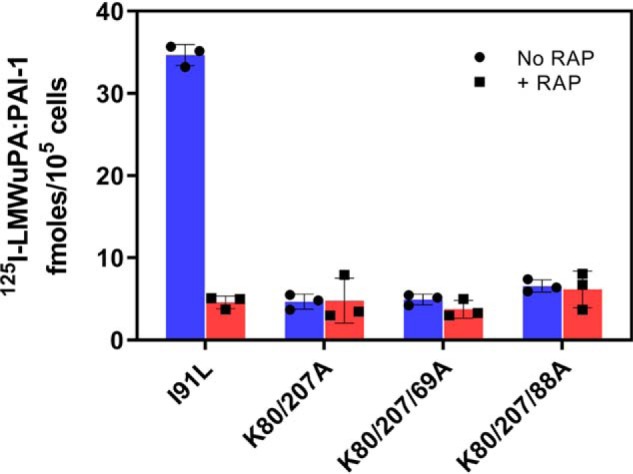

We next examined the cellular uptake of complexes of PAI-1 with LMWuPA formed from PAI-1 molecules containing double or triple mutations (Fig. 9). The results reveal that when complexed to LMWuPA at low concentrations (5 nm), the double and triple mutants of PAI-1 were not effectively taken up by cells expressing LRP1.

Figure 9.

LRP1-mediated cellular uptake of LMWuPA:PAI-1 is reduced when complex is formed with PAI-1-containing mutations in lysine residues. 5 nm 125I-labeled LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes formed with I91L PAI-1 or the indicated mutant PAI-1 molecules were incubated with WI-38 human fibroblasts for 6 h at 37 °C in the absence or presence of excess RAP. Following incubation, the amount of internalized complex was quantified. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Discussion

The ability of LRP1 and other members of the LDL receptor family to recognize a large repertoire of ligands with remarkably high affinity has raised questions regarding the nature of the interaction between these receptors and their ligands. Early studies recognized the importance of basic amino acids on the ligand that seemed critical for receptor binding. For example, these studies confirmed that basic residues were critical for the binding of apolipoprotein E to the LDL receptor (31, 32), whereas mutagenesis studies confirmed a critical role for Lys-1370 in α2-macroglobulin for binding of its activated form to LRP1 (15). Furthermore, mutagenesis studies on RAP, a molecule composed of three domains, identified critical roles for Lys-60 and Lys-191 in the high-affinity binding of the first two domains to LRP1 (30) and a critical role for Lys-256 and Lys-270 for binding of domain 3 to LRP1 (13).

A key discovery was made when solving the structure of two LDLa repeats from the LDL receptor in complex with the third domain of RAP (14). Despite the fact that RAP only binds weakly to the LDL receptor (33), this work provided a basis for ligand recognition by this family of receptors by revealing that three acidic residues from each LDL receptor module formed an acidic pocket for the two lysine side chains (Lys-256 and Lys-270) from RAP. The acidic pocket on the receptors is stabilized by a calcium ion, and the interaction with ligand is strengthened by an aromatic residue on the receptor that forms van der Waals interactions with the aliphatic portion of the lysine residue that is docked in the “acidic pocket” (14) and by other lysine residues on ligands that form weak electrostatic interactions (34). Subsequent studies have supported this model using various LDLa repeats from a number of LDL receptor family members in complex with ligands (35–39). Based on these studies, it has been proposed that avidity effects resulting from the use of multiple sites located on the ligand and receptor result in high-affinity binding and serve as a model to describe the versatility of this receptor family in recognizing so many different ligands.

In the case of PAI-1, a number of studies have identified specific amino acid residues that contribute to its interaction with LRP1 (18–20, 25). Together, these studies have implicated Lys-88, Lys-80, Lys-69, and Arg-76 as important contributors to the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1. Analysis of existing structural data suggests that Arg-76 is not likely to be directly involved in the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1, which was confirmed in this study. Interestingly, our study uncovered important differences in the impact of this residue on LRP1 binding that depends on the background of PAI-1 (i.e. 14-1B versus I91L mutants). The sensitivity of the 14-1B background to the effects of the R76E mutation likely reflect the unique conformational effects that the mutations in 14-1B have on the LRP1-binding surface shown in Fig. 10. In 14-1B PAI-1, there is a new hydrogen-bonding network formed between residues in the loop connecting α-helix F with β-strand 3A and Glu-283 in β-strand 6A (40). This holds β-sheet A in a closed conformation and prevents conversion to the latent conformation (41). This also directly affects the LRP1-binding surface by restricting mobility of α-helix D and the loop connecting helix D to β-strand 2A that contain LRP1-binding residues Lys-80 and Lys-88, respectively.

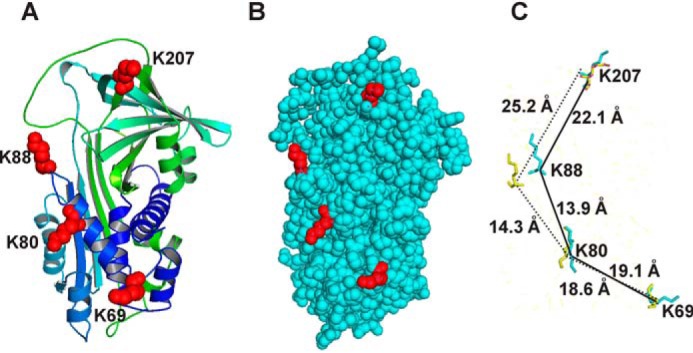

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional structure of PAI-1 showing the locations of lysine residues 207, 88, 80, and 69. A, ribbon diagram of native PAI-1 with lysine residues colored red. B, space-filling model of native PAI-1; lysine residues are shown in red. C, orientation of Lys-207, Lys-88, Lys-80, and Lys-69 in native PAI-1 (yellow) aligned with latent PAI-1 (teal) using PyMOL software. (Coordinates for native PAI-1 are from PDB code 1DB2 and for latent PAI-1 are from PDB code 1LJ5.)

This study confirms the contributions of Lys-69, Lys-88, and Lys-80 in the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1 as mutation of these residues to alanine results in a 7-, 7-, and 9-fold decrease in affinity for LRP1, respectively. Importantly, our studies identify a critical role for Lys-207 in the interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1 as mutation of this residue to alanine resulted in a 19-fold weaker binding of PAI-1 to LRP1. Our data support a model in which two critical lysine residues on PAI-1 participate in binding. First, by examining the ionic strength dependence of binding, we observed a slope of 1.5 ± 0.1 from the Debye-Hückel plots suggesting the involvement of two charged residues. Second, analysis of the binding kinetics reveals an excellent fit of the data to a bivalent binding model, consistent with this notion. Although it is possible that two binding regions located on LRP1 might be located on different clusters of LDLa repeats, the fact that the binding kinetics and affinity of PAI-1 for the cluster IV region of LRP1 are identical to that of the intact molecule reveals that the two LRP1-binding regions can also be located within a single cluster of LDLa repeats.

Our studies also confirm that upon forming a complex with a protease, the protease:PAI-1 complex displays an approximate 100-fold increase in affinity for LRP1, in agreement with the majority of published data (21, 23, 42). The increased affinity of uPA:PAI-1 complexes for LRP1 over free PAI-1 raises questions regarding the nature of the interactions involved. Our data provide insight into how this may occur at the molecular level and suggest that in the uPA:PAI-1 complex, three lysine residues on PAI-1 interact with LRP1. The additional avidity effects resulting from the interaction of three regions of the uPA:PAI-1 complex with LDLa repeats on LRP1 would be expected to have significant increases in affinity of the uPA:PAI-1 complex for LRP1. This model is supported by several observations. First, we found that chemical modification of lysine residues on PAI-1 completely blocked recognition of the LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex by LRP1, revealing a critical role for PAI-1 lysine residues in mediating the interaction between uPA:PAI-1 complexes and LRP1. Second, our ionic strength data revealed a slope of 2.4 ± 0.3 from the Debye-Hückel plots suggesting the involvement of three charged residues in the interaction of uPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1.

Finally, our mutational analysis also supports this notion. We noted, for example, that although a single mutation of Lys-69, Lys-80, Lys-88, and Lys-207 all impacted the binding of PAI-1 to LRP1, mutation of these residues had minimal impact on the binding of LMWuPA:PAI complexes to LRP1. Furthermore, although mutational analysis of two lysine residues (Lys-80 and Lys-207) on PAI-1 resulted in a significant loss in affinity of free PAI-1 (20-fold decrease) and uPA:PAI-1 (26-fold decrease) for LRP1, mutation of a third residue (Lys-88) had little additional impact on the binding of free PAI-1 to LRP1, but it had a significant impact on the binding of uPA:PAI-1 complexes to LRP1 (Table 4) reducing the affinity by 244-fold. Together, these data support the hypothesis that the primary interaction of PAI-1 with LRP1 involved pairs of lysine residues, whereas the interaction of uPA:PAI-1 complexes with LRP1 involves three lysine residues.

Table 4.

Distances between Cα lysine residues in various conformations of PAI-1 and alignment of the structure of native PAI-1 with the structure of other forms of PAI-1

| Serpin | Structures | Distancea Lys-207–Lys-88 (Å) | Distance Lys-88–Lys-80 (Å) | Distance Lys-207–Lys-80 (Å) | Distance Lys-80–Lys-69 (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native PAI-1 | PDB code 1db2 | 25.2 | 14.3 | 31.6 | 18.6 |

| Cleaved PAI-1 | PDB code 3cvm | 21.6 | 13.4 | 31.3 | 18.9 |

| Latent PAI-1 | PDB code 1Lj5 | 22.1 | 13.9 | 32.2 | 19.1 |

| uPA:PAI-1 Michaelis complex | PDB code 3pb1 | 24.2 | 14.9 | 31.1 | 19.0 |

| Alignment | Structures | Shift in Lys-207 (Å)b | Shift in Lys-88 (Å)b | Shift in Lys-80 (Å)b | Shift in Lys-69 (Å) (Å)b |

| Native vs. cleaved PAI-1 | PDB code 1db2 vs. 3cvm | 0.3 | 6.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Native vs. latent PAI-1 | PDB code 1db2 vs. 1Lj5 | 0.8 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Native vs. uPA:PAI-1 Michaelis complex | PDB code 1db2 vs. 3pb1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

a Distances were measured using PyMOL software.

b Data were determined by aligning the indicated structures using PyMOL software.

It has been previously proposed that PAI-1 contains a high-affinity cryptic binding site that is exposed upon complex formation with either tissue plasminogen activator or uPA (18, 21), which is consistent with our data in this study. This has been questioned, however, because the structure of native PAI-1 is similar to that of cleaved PAI-1 (3). It should be highlighted, however, that a structure of the protease:PAI-1 complex is not yet available. Interestingly, Lys-207, Lys-88, Lys-80, and Lys-69 are all located on one surface of PAI-1 (Fig. 10, A and B). In native PAI-1, they are spaced 25.2, 14.3, and 18.6 Å apart, respectively, and in latent PAI-1, these residues are spaced 22.1, 13.9, and 19.1 Å apart (Fig. 10 and Table 4). Alignment of the three-dimensional structures of native PAI-1 with various forms of PAI-1 reveal that Lys-88 is shifted by 6.1 and 6.0 Å in cleaved or latent PAI-1, respectively (Fig. 10C and Table 4), suggesting that the conformational change occurring in PAI-1 upon complex formation may optimally align critical lysine residues for LRP1 recognition.

The results from this study differ substantially from those described by Gettins and Dolmer (43), who reported high-affinity binding of native PAI-1 to three LDLa repeats, termed CR456, derived from cluster II of LRP1 (KD = 1.5 nm). Although different approaches were used to measure the binding of PAI-1, this is not likely the cause of the discrepancy. The weaker affinity for PAI-1 observed in our study is consistent with our previous observation that cells are not able to effectively bind and mediate the endocytosis of nanomolar levels of PAI-1 in the absence of protease (21). In our view, a more likely explanation is that the difference between the affinity of PAI-1 for intact LRP1 and for small fragments of LRP1 might arise from flexibility between the LDLa repeats of the CR456 fragment versus a more rigid full-length LRP1 molecule. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the CR456 fragment has a 10-amino acid spacer between CR5 and CR6, suggesting some flexibility is associated with this fragment. We propose that in the full-length receptor these repeats may not be as flexible as in the CR456 fragment, which could account for the different results obtained between the two studies.

In summary, our studies support the concept that high-affinity binding of PAI-1 to LRP1 requires complex formation with a protease. Furthermore, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that complex formation results in a conformational change in PAI-1, which optimizes the presentation of Lys-88 on PAI-1 that is capable of docking into acidic pockets on the LDLa repeats of LRP1 generating the scaffolding for high-affinity binding.

Experimental procedures

Reagents

LMWuPA, HMWuPA, WT PAI-1, and I91L PAI-1 were purchased from Molecular Innovations. Mutant PAI-1 proteins were produced and purified as described previously (26, 44). LRP1 was purified from human placenta as described previously (5). LRP1 ligand-binding clusters II–IV were purchased from R&D SystemsTM. CDE096 was synthesized as described previously (28). LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes used for Biacore studies were formed by incubating PAI-1 with 1.2-fold molar excess of LMWuPA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. HMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes were purchased from Molecular Innovation. Complex formation was verified by analyzing proteins on 4–20% Tris-Gly gel (Novex) and staining with colloidal blue stain.

Chemical modification of I91L PAI-1

Chemical modification of I91L PAI-1 to block the primary amines in lysine side chains was performed using sulfo-NHS-acetate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sulfo-NHS-acetate was dissolved in PBS at 50 mg/ml. 55 μg of I91L PAI1 was incubated with 50-fold excess of the sulfo-NHS-acetate over total amino groups in I91L PAI-1 in PBS for 3 h at 4 °C. The modified I91L PAI-1 protein was desalted into 0.01 m HEPES, 0.15 m NaCl, pH 7.4, using NAPTM-5 Sephadex G-25 column (GE Healthcare) to remove the excess sulfo-NHS-acetate.

Surface plasmon resonance

Purified LRP1 was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip surface to the level of 10,000 response units, using a working solution of 20 μg/ml LRP1 in 10 mm sodium acetate, pH 4. LRP1 ligand-binding cluster IV was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip surface to the level of 2000 response units, using a working solution of 20 μg/ml cluster IV in 10 mm sodium acetate, pH 4, according to the manufacturer's instructions (BIAcore AB). An additional flow cell was activated and blocked with 1 m ethanolamine without protein to act as a control surface. Unless otherwise stated, the binding experiments were performed in HBS-P buffer (0.01 m HEPES, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.005% surfactant P, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4). For ionic strength dependence, buffers were made with 10 mm HEPES, .0005% surfactant P, 1 mm CaCl2 with various concentrations of NaCl (0.15, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 m), pH 7.4. All experiments were performed on a BIAcore 3000 instrument, using a flow rate of 20 μl/min at 25 °C. Sensor chip surfaces were regenerated by 15-s injections of 100 mm phosphoric acid at a flow rate of 100 μl/min.

SPR data analysis

Dissociation rates were fit to a two-exponential decay using GraphPad Prism 7.04 software. Kinetic data were analyzed to a bivalent model (Scheme 1) using BIAevaluation software,

where A represents ligand (PAI-1 or LMWuPA:PAI-1 complex); B represents LRP1; AB1 represents the ligand:LRP1 complex in which on region of the ligand is complexed with LRP1; and AB2 represents the bivalent ligand:LRP1 complex at site 2. To facilitate the fitting process, estimates for kd1 and kd2 were obtained by fitting the dissociation data globally to a two-exponential decay model. These values were then used as initial estimates in the fitting process. In the case of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes, the data were fit to Schemes 2 and 3, as described previously (30):

and

Equilibrium-binding data were determined by fitting the association rates to a pseudo-first-order process to obtain Req. Req was then plotted against total ligand concentration and fit to a binding isotherm using nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism 7.04 software as shown in Equation 1,

| (Eq. 1) |

where Bmax is the Req value at saturation; L is the free ligand concentration, and KD is the equilibrium binding constant. Because the free ligand concentration is unknown in these experiments, the use of Equation 1 assumes that the total amount of added ligand is far greater than the amount of ligand bound to the LRP-1 coupled SPR chip.

Inhibition by CDE-096

HMWuPA:PAI-1 complex was diluted to 2 nm in 0.01 m HEPES, 0.15 m NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 0.0005% surfactant P, 0.1% DMSO, pH 7.8, containing 0 to 500 nm CDE-096. Binding to LRP1 was examined by SPR analysis as described earlier except that the equilibration buffer was 0.01 m HEPES, 0.15 m NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 0.0005% surfactant P, 0.1% DMSO, pH 7.8.

Uptake of LMWuPA:PAI-1 complexes by cells

WI38 cells were plated in 12-well tissue culture plates previously coated with poly-d-lysine hydrobromide (Sigma). Cells were incubated in assay buffer (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 1% BSA, 20 mm HEPES) for 1 h before treating with iodinated complex. LMWuPA was iodinated with 125I-sodium iodide (PerkinElmer Life Sciences NEZ033) using Iodo-Gen (Pierce) in PBS containing 1 mm 6-aminocaproic acid (Aldrich). Iodinated protein was desalted into PBS using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) to remove free iodine. Labeled complex was formed by incubating I91L PAI-1 and its mutants (0.8 μm) with 125I-labeled LMWuPA (0.4 μm) for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting complex was diluted to 5 nm in assay buffer alone or assay buffer containing 1 μm RAP and placed on cells for 6 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the media were removed, and cells were washed with 2 ml of PBS and treated with trypsin (Corning 25–0520) containing 50 μg/ml proteinase K. Cells were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 4 min. Supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was counted to determine moles internalized.

Author contributions

M. M., S.-H. L., C. D. E., D. A. L., and D. K. S. conceptualization; M. M., A. Z., C. D. E., D. A. L., and D. K. S. data curation; M. M., C. D. E., D. A. L., and D. K. S. formal analysis; M. M., C. D. E., and D. A. L. investigation; M. M., C. D. E., and D. K. S. methodology; S.-H. L., C. D. E., D. A. L., and D. K. S. writing-original draft; S.-H. L., C. D. E., D. A. L., and D. K. S. writing-review and editing; C. D. E. and D. K. S. resources; C. D. E., D. A. L., and D. K. S. funding acquisition; D. A. L. and D. K. S. project administration.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R35 HL135743 (to D. K. S.) and HL55374 (to D. A. L.) and American Heart Association Grant 7UFEL334700001 (to A. Z.). C. D. E. and D. A. L. are inventors on patent applications related to CDE-096. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- uPA

- urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- PAI-1

- plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1

- I91L PAI-1

- PAI-1 in which leucine 91 is mutated to isoleucine

- 14-1B PAI-1

- stable PAI-1 with following mutations: N150H, K154T, Q319L, and M354I

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- LRP1

- LDL receptor–related protein 1

- LDLa repeats

- low-density lipoprotein class A repeats

- LMWuPA

- low-molecular-weight urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- HMWuPA

- high-molecular-weight urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- sulfo-NHS-acetate

- sulfosuccinimidyl acetate

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- LMWuPA:PAI-1

- complex of low-molecular-weight urokinase-type plasminogen inhibitor with plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1

- HMWuPA:PAI-1

- complex of high-molecular-weight urokinase-type plasminogen inhibitor with plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1

- RAP

- receptor-associated protein

- α2M

- α2-macroglobulin

- ASA

- accessible surface area

- Req

- SPR response at equilibrium.

References

- 1. Li S.-H., and Lawrence D. A. (2011) Development of inhibitors of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Methods Enzymol. 501, 177–207 10.1016/B978-0-12-385950-1.00009-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flevaris P., and Vaughan D. (2017) The role of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 in fibrosis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 43, 169–177 10.1055/s-0036-1586228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gettins P. G., and Olson S. T. (2016) Inhibitory serpins. New insights into their folding, polymerization, regulation and clearance. Biochem. J. 473, 2273–2293 10.1042/BCJ20160014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kounnas M. Z., Church F. C., Argraves W. S., and Strickland D. K. (1996) Cellular internalization and degradation of antithrombin III–thrombin, heparin cofactor II–thrombin, and α1-antitrypsin–trypsin complexes is mediated by the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6523–6529 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashcom J. D., Tiller S. E., Dickerson K., Cravens J. L., Argraves W. S., and Strickland D. K. (1990) The human α2-macroglobulin receptor: identification of a 420-kD cell surface glycoprotein specific for the activated conformation of α2-macroglobulin. J. Cell Biol. 110, 1041–1048 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moestrup S. K., and Gliemann J. (1989) Purification of the rat hepatic α2-macroglobulin receptor as an approximately 440-kDa single chain protein. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 15574–15577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rohlmann A., Gotthardt M., Hammer R. E., and Herz J. (1998) Inducible inactivation of hepatic LRP gene by Cre-mediated recombination confirms role of LRP in clearance of chylomicron remnants. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 689–695 10.1172/JCI1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gonias S. L. (2018) Mechanisms by which LRP1 maintains arterial integrity: keeping your vascular smooth muscle happy and healthy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, 2548–2549 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strickland D. K., Au D. T., Cunfer P., and Muratoglu S. C. (2014) Low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein-1: role in the regulation of vascular integrity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 487–498 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Strickland D. K., Ashcom J. D., Williams S., Battey F., Behre E., McTigue K., Battey J. F., and Argraves W. S. (1991) Primary structure of α2-macroglobulin receptor-associated protein–human homologue of a Heymann nephritis antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 13364–13369 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willnow T. E., Armstrong S. A., Hammer R. E., and Herz J. (1995) Functional expression of low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein is controlled by receptor-associated protein in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 4537–4541 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bu G., Geuze H. J., Strous G. J., and Schwartz A. L. (1995) 39-kDa receptor-associated protein is an ER resident protein and molecular chaperone for LDL receptor-related protein. EMBO J. 14, 2269–2280 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07221.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Migliorini M. M., Behre E. H., Brew S., Ingham K. C., and Strickland D. K. (2003) Allosteric modulation of ligand binding to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein by the receptor-associated protein requires critical lysine residues within its carboxyl-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17986–17992 10.1074/jbc.M212592200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisher C., Beglova N., and Blacklow S. C. (2006) Structure of an LDLR-RAP complex reveals a general mode for ligand recognition by lipoprotein receptors. Mol. Cell 22, 277–283 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arandjelovic S., Hall B. D., and Gonias S. L. (2005) Mutation of lysine 1370 in full-length human α2-macroglobulin blocks binding to the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 438, 29–35 10.1016/j.abb.2005.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van den Biggelaar M., Madsen J. J., Faber J. H., Zuurveld M. G., van der Zwaan C., Olsen O. H., Stennicke H. R., Mertens K., and Meijer A. B. (2015) Factor VIII interacts with the endocytic receptor low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 via an extended surface comprising “hot-spot” lysine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 16463–16476 10.1074/jbc.M115.650911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Young P. A., Migliorini M., and Strickland D. K. (2016) Evidence that factor VIII forms a bivalent complex with the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1): identification of cluster IV on LRP1 as the major binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 26035–26044 10.1074/jbc.M116.754622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horn I. R., van den Berg B. M., Moestrup S. K., Pannekoek H., and van Zonneveld A.-J. (1998) Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 contains a cryptic high affinity receptor binding site that is exposed upon complex formation with tissue-type plasminogen activator. Thromb. Haemost. 80, 822–828 10.1055/s-0037-1615365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodenburg K. W., Kjoller L., Petersen H. H., and Andreasen P. A. (1998) Binding of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 complex to the endocytosis receptors α2-macroglobulin receptor/low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor involves basic. Biochem. J. 329, 55–63 10.1042/bj3290055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gettins P. G., and Dolmer K. (2016) The high affinity binding site on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) for the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP1) is composed of four basic residues. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 800–812 10.1074/jbc.M115.688820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stefansson S., Muhammad S., Cheng X.-F., Battey F. D., Strickland D. K., and Lawrence D. A. (1998) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 contains a cryptic high affinity binding site for the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6358–6366 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nykjaer A., Petersen C. M., Møller B., Jensen P. H., Moestrup S. K., Holtet T. L., Etzerodt M., Thøgersen H. C., Munch M., Andreasen P. A., and Gliemann J. (1992) Purified α2-macroglobulin receptor/LDL receptor-related protein binds urokinase plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 complex. Evidence that the α2-macroglobulin receptor mediates cellular degradation of urokinase receptor-bound complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 14543–14546 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horn I. R., van den Berg B. M., van der Meijden P. Z., Pannekoek H., and van Zonneveld A. J. (1997) Van molecular analysis of ligand binding to the second cluster of complement-type repeats of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13608–13613 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jensen J. K., Dolmer K., and Gettins P. G. (2009) Specificity of binding of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein to different conformational states of the clade E serpins plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and proteinase nexin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17989–17997 10.1074/jbc.M109.009530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Skeldal S., Larsen J. V., Pedersen K. E., Petersen H. H., Egelund R., Christensen A., Jensen J. K., Gliemann J., and Andreasen P. A. (2006) Binding areas of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 complex for endocytosis receptors of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family, determined by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS J. 273, 5143–5159 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thompson L. C., Goswami S., Ginsberg D. S., Day D. E., Verhamme I. M., and Peterson C. B. (2011) Metals affect the structure and activity of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. I. Modulation of stability and protease inhibition. Protein Sci. 20, 353–365 10.1002/pro.568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berkenpas M. B., Lawrence D. A., and Ginsburg D. (1995) Molecular evolution of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 functional stability. EMBO J. 14, 2969–2977 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07299.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li S.-H., Reinke A. A., Sanders K. L., Emal C. D., Whisstock J. C., Stuckey J. A., and Lawrence D. A. (2013) Mechanistic characterization and crystal structure of a small molecule inactivator bound to plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E4941–E4949 10.1073/pnas.1216499110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willard L., Ranjan A., Zhang H., Monzavi H., Boyko R. F., Sykes B. D., and Wishart D. S. (2003) VADAR: a web server for quantitative evaluation of protein structure quality. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3316–3319 10.1093/nar/gkg565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Prasad J. M., Young P. A., and Strickland D. K. (2016) High affinity binding of the receptor-associated protein D1D2 domains with the low density lipoprotein receptor related protein (LRP1) involves bivalent complex formation: critical roles of lysines 60 and 191. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 18430–18439 10.1074/jbc.M116.744904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahley R. W., Innerarity T. L., Pitas R. E., Weisgraber K. H., Brown J. H., and Gross E. (1977) Inhibition of lipoprotein binding to cell surface receptors of fibroblasts following selective modification of arginyl residues in arginine rich and B apoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 7279–7287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weisgraber K. H., Innerarity T. L., and Mahley R. W. (1978) Role of the lysine residues of plasma lipoproteins in high affinity binding to cell surface receptors on human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 9053–9062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Medh J. D., Bowen S. L., Fry G. L., Ruben S., Andracki M., Inoue I., Lalouel J.-M., Strickland D. K., and Chappell D. A. (1996) Lipoprotein lipase binds to low density lipoprotein receptors and induces receptor-mediated catabolism of very low density lipoproteins in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17073–17080 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dolmer K., Campos A., and Gettins P. G. (2013) Quantitative dissection of the binding contributions of ligand lysines of the receptor-associated protein (RAP) to the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP1). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 24081–24090 10.1074/jbc.M113.473728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yasui N., Nogi T., Kitao T., Nakano Y., Hattori M., and Takagi J. (2007) Structure of a receptor-binding fragment of reelin and mutational analysis reveal a recognition mechanism similar to endocytic receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9988–9993 10.1073/pnas.0700438104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verdaguer N., Fita I., Reithmayer M., Moser R., and Blaas D. (2004) X-ray structure of a minor group human rhinovirus bound to a fragment of its cellular receptor protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 429–434 10.1038/nsmb753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jensen G. A. Andersen O. M., Bonvin A. M., Bjerrum-Bohr I., Etzerodt M., Thøgersen H. C., O'Shea C., Poulsen F. M., and Kragelund B. B. (2006) Binding site structure of one LRP–RAP complex: implications for a common ligand-receptor binding motif. J. Mol. Biol. 362, 700–716 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee C. J., De Biasio A., and Beglova N. (2010) Mode of interaction between β2GPI and lipoprotein receptors suggests mutually exclusive binding of β2GPI to the receptors and anionic phospholipids. Structure 18, 366–376 10.1016/j.str.2009.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guttman M., Prieto J. H., Handel T. M., Domaille P. J., and Komives E. A. (2010) Structure of the minimal interface between ApoE and LRP. J. Mol. Biol. 398, 306–319 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharp A. M., Stein P. E., Pannu N. S., Carrell R. W., Berkenpas M. B., Ginsburg D., Lawrence D. A., and Read R. J. (1999) The active conformation of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, a target for drugs to control fibrinolysis and cell adhesion. Structure 7, 111–118 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li S. H., Gorlatova N. V., Lawrence D. A., and Schwartz B. S. (2008) Structural differences between active forms of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 revealed by conformationally sensitive ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18147–18157 10.1074/jbc.M709455200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nykjaer A., Kjøller L., Cohen R. L., Lawrence D. A., Garni-Wagner B. A., Todd R. F. 3rd., van Zonneveld A. J., Gliemann J., and Andreasen P. A. (1994) Regions involved in binding of urokinase-type-1 inhibitor complex and pro-urokinase to the endocytic α2-macroglobulin receptor/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Evidence that the urokinase receptor protects pro-urokinase against binding. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 25668–25676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gettins P. G., and Dolmer K. (2012) A proximal pair of positive charges provides the dominant ligand-binding contribution to complement-like domains from the LRP (low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein). Biochem. J. 443, 65–73 10.1042/BJ20111867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gorlatova N. V., Elokdah H., Fan K., Crandall D. L., and Lawrence D. A. (2003) Mapping of a conformational epitope on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by random mutagenesis: implications for serpin function. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16329–16335 10.1074/jbc.M208420200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]