Dear editor,

Doubled haploid (DH) technology substantially accelerates crop breeding process. Wheat haploid production through interspecific hybridization requires embryo rescue and is dependent on genetic background. In vivo haploid induction (HI) in maize has been widely used and demonstrated to be independent of genetic background and to produce haploids efficiently. Recent studies revealed that loss‐of‐function of the gene MTL/ZmPLA1/NLD triggers HI (Gilles et al., 2017; Kelliher et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017). In addition to producing homozygous DH lines, HI system has also been used for gene editing in different genetic backgrounds without introducing the genome of the male parent (Kelliher et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019).

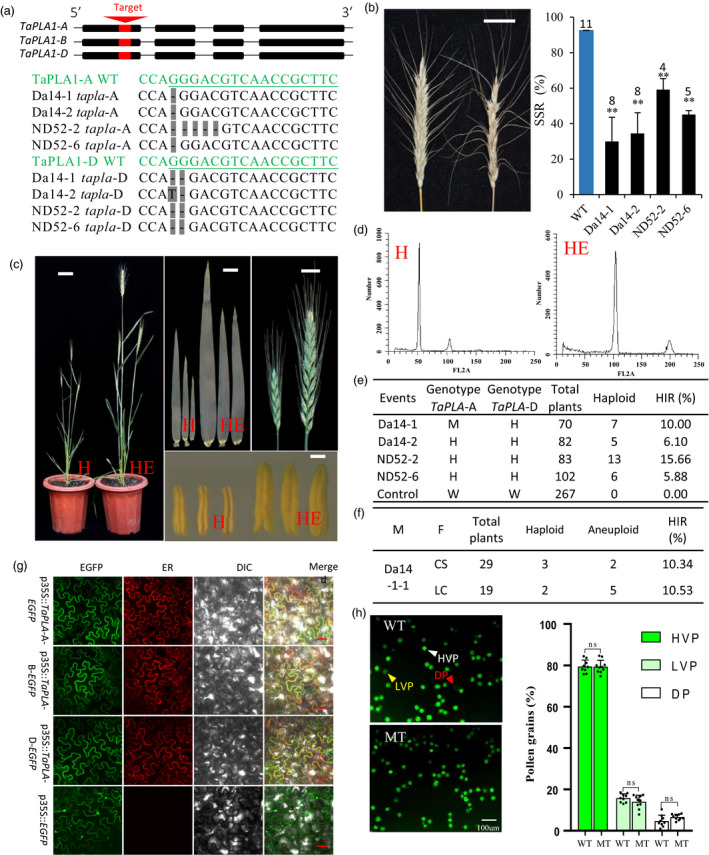

Importantly, HI system had been successfully applied to rice (Yao et al., 2018), making this method more promising. However, little is known whether it can be applied to polyploids. Extension of the maize HI to wheat would create a novel approach in producing haploids in both wheat and other polyploid crop species. In this study, full‐length amino acid sequence encoded by MTL/ZmPLA1/NLD was used to do BLAST search for homologues genes in different crop species (www.gramene.com). Results showed that the gene is highly conserved among 19 species of Liliopsida. Wheat homologues genes sharing ~70%‐80% amino acid sequence identity with maize. Wheat genome contains three homologues genes: TraesCS4A02G018100 (TaPLA‐A), TraesCS4B02G286000 (TaPLA‐B) and TraesCS4D02G284700 (TaPLA‐D), located on chromosomes 4A, 4B and 4D, respectively. All three includes four exons (Figure 1a). The DNA sequence identity between each of the three homologues genes and MTL/ZmPLA1/NLD is 75%, representing a high level of sequence conservation. The amino acid sequence identity among the three TaPLA genes is 96%.

Figure 1.

Knockout of wheat homologues genes of MTL /ZmPLA1/ NLD triggers HI. (a) Gene structure of Ta PLA ‐A, Ta PLA ‐B and T a PLA ‐D and knockout experiment. Exons in red are target regions of guide RNAs. Shown below are guide RNA (green) and sequence of transgenic lines Da14‐1, Da14‐2, ND52‐2 and ND52‐6 at TaPLA ‐A and TaPLA ‐D (black), respectively. Deletions are shown by ‘‐’ on grey background. (b) Spike performance of wild type (left) and knockout (right) plants. Statistical analysis for SSR of wild type and four transgenic lines is shown on the right side. ** P < 0.01 calculated with the heteroscedastic two‐tailed Student's t‐test. Sample size is marked on the top of each column. (c) Phenotypic difference between haploid (H) and hexaploid (HE) wheat, including whole plant, leaf, ear and anther. Bars = 5 cm, 1 cm, 1 cm and 1 mm for whole plant, flag leaf, ear and anther, respectively. (d) Ploidy verification with flow cytometry analysis. (e) HI potential of transgenic lines and control in self‐pollination progeny. Genotype Ta PLA ‐A and genotype T aPLA ‐D: H, heterozygous, means one copy from two TaPLA alleles had been edited; M, homozygous mutant, means both copies of TaPLA had been edited, either the same mutation or different; and W, wild type, means neither of two copies of TaPLA had been edited. The control group comprised self‐pollinated plants from wild type CB037. (f) HI potential in cross progeny. M, male parent; F, female parent; CS, Chinese Spring; LC, Liaochun10. (g) Subcellular localization of TaPLAs in tobacco epidermal cells. Confocal scanning (GFP; outside left), ER‐mCherry signal (inside left), differential interference contrast (DIC; inside right), and merged (outside right) micrographs of tobacco epidermal cells transformed with a 35S::TaPLA‐AEGFP, 35S::TaPLA‐B‐EGFP, 35S::TaPLA‐D‐EGFP and 35S::EGFP control. Scale bars = 30 μm. (h) Pollen viability assays with FDA staining. Comparison of pollen viability between wild type and mutants in CB037 background (scale bar, 100 μm) (left). Pollen with a strong (white triangle) and weak (yellow triangle) or no (red triangle) GFP represented for high‐viability pollen (HVP), low‐viability pollen (LVP) and dead pollen (DP), respectively. Ratio of the three viability classes in wild type and mutant pollen (right). Statistics were conducted with three biological replicates. A heteroscedastic two‐tailed Student's t‐test was performed for each class between wild type and mutant. NS, not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

Next, we designed two guide RNA sequences, one targeted TaPLA‐B and TaPLA‐D (gRNA1), and another targeted TaPLA‐A and TaPLA‐D (gRNA2) to create knockout lines using CRISPR/Cas9 (Figure 1a). After Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation into CB037, four transgenic events were obtained with mutations on both TaPLA‐A and TaPLA‐D. None of them had a mutation on TaPLA‐B. Sequencing results of four transgenic events are shown in Figure 1a. Although different in sequence, all these mutations led to frameshifts and loss of function for both TaPLA‐A and TaPLA‐D (Figure 1a).

These T0 transgenic and control plants were grown in greenhouse. No obvious phenotypic difference was found between wild‐type and transgenic plants, except for the seed setting rate (SSR), which ranged from ~30% to ~60% in transgenic lines, significantly lower than the average value of 92.6% in wild type (Figure 1b), implying that TaPLAs may be involved in sexual reproduction. Importantly, putative haploid plants were found in self‐pollinated progenies of all four transgenic lines according to their growth characteristics. Average HI rate (HIR) ranged from 5.88% to 15.66% (Figure 1e). In the progeny of T1 × Chinese Spring and T1 × Liaochun10, 3 and 2 putative haploids were found in 29 and 19 individuals, respectively (Figure 1f). To verify real ploidy level of putative haploids, flow cytometry was used. Results showed that compared with hexaploid controls which had FL2A peaks approximately 100, all putative haploids had FL2A peaks approximately 50 (Figure 1d), suggesting that putative haploids identified by phenotypic characteristics were true haploids. These haploids had shorter plant height, narrower leaves, shorter spikes and male sterility (Figure 1c). No haploid plant was identified in a control group with 267 progenies from wild type individuals (Figure 1e). Therefore, we concluded that knockout of wheat homologues genes of MTL/ZmPLA1/NLD could trigger wheat haploid induction. The HIR reported here was higher than that in previous preprint version, this was because more haploids were identified later. Since the inducer lines (T0) still contained active Cas9, there was the possibility that floral organ genotype might be different from leaf and had homozygous mutations. In addition to haploids, 7 aneuploids were found among crossed progeny, including 1 plant with ploidy level between haploid and hexaploid and 6 plants with ploidy level higher than hexaploid. This phenomenon may provide some clues on mechanism of wheat HI.

To characterize the expression pattern of the TaPLA s, subcellular localization was performed using tobacco epidermal cells. As shown in Figure 1g, all three genes showed strong signals in plasma membrane and merged well with the endoplasmic reticulum marker. This result is consistent with NLD in maize (Gilles et al., 2017). Chromosome elimination and single fertilization were two leading hypotheses in explaining HI in maize (Kelliher et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2018). While other issues like low pollen viability which may also contribute to haploid induction, had not been fully ruled out. Here, we performed fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining to examine pollen viability in wild type and mutants. There was no difference in the proportion of pollen viability classes between mutants and wild type (Figure 1h). Therefore, loss of function of both TaPLA‐A and TaPLA‐D does not influence pollen viability.

Several technical problems require further investigation before HI can be applied efficiently in wheat, including how to further improve wheat HI efficiency and the difficulties in haploid kernel identification. Considering the potential redundancy among TaPLA‐A, TaPLA‐B and TaPLA‐D, wild type TaPLA‐B may functionally complement tapla‐A and tapla‐D double mutant. Nevertheless, the complement effect is not enough to rescue the phenotype of HI and reduced SSR. On the other hand, further improvement of HI efficiency in wheat may be achieved by creating triple mutants. In addition, the gene ZmDMP contributing to HIR has been identified (Liu et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2019), and the efficiency of wheat HI may be further improved by knockout ZmDMP homologues genes in wheat. On the other hand, recent studies have simplified the identification of haploids using enhanced green fluorescent proteins and DsRed signals specifically expressed in the embryo and endosperm, respectively (Dong et al., 2018). This method may provide a potential solution for haploid kernel identification in wheat.

In summary, our study provided the proof that HI is not limited to diploid crop species but can be extended to polyploid species. Meanwhile, this study also provided a promising platform for wheat haploid gene editing and mechanism studies of HI. Considering the conservation of gene sequence and function, the system could potentially be extended to a wider variety of crop species.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

S.C. and C.L. conceived and designed the project. C.L. and Y.Z. constructed plasmid. X.Q., Y.Z., M.C. and Z.L. planted transgenic plants in greenhouse and performed haploid identification and verification and phenotype investigations. Y.Z., C.L., X.Q., M.L. and W.L. performed data analysis. C.L., Y.Z., X.Q., M.X. and S.C. wrote the paper with inputs from all authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Pu Wang for providing greenhouse, Prof. Zhongfu Ni for providing CB037 seeds, Prof. Xingguo Ye for wheat transformation and Dr. Qiguo Yu for carefully reading the manuscript. This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101200), the Modern Maize Industry Technology System (CARS‐02‐04) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M631634).

References

- Dong, L. , Li, L. , Liu, C. , Liu, C. , Geng, S. , Li, X. , Huang, C. et al. (2018) Genome editing and double‐fluorescence proteins enable robust maternal haploid induction and identification in maize. Mol Plant, 11, 1214–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, L.M. , Khaled, A. , Laffaire, J.B. , Chaignon, S. , Gendrot, G. , Laplaige, J. , Bergès, H. et al. (2017) Loss of pollen‐specific phospholipase NOT LIKE DAD triggers gynogenesis in maize. EMBO J. 36, 707–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, T. , Starr, D. , Richbourg, L. , Chintamanani, S. , Delzer, B. , Nuccio, M.L. , Green, J. et al. (2017) MATRILINEAL, a sperm‐specific phospholipase, triggers maize haploid induction. Nature, 542, 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, T. , Starr, D. , Su, X. , Tang, G. , Chen, Z. , Carter, J. , Wittich, P.E. et al. (2019) One‐step genome editing of elite crop germplasm during haploid induction. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , Li, W. , Zhong, Y. , Dong, X. , Hu, H. , Tian, X. , Wang, L. et al. (2015) Fine mapping of qhir8 affecting in vivo haploid induction in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128, 2507–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , Li, X. , Meng, D. , Zhong, Y. , Chen, C. , Dong, X. , Xu, X. et al. (2017) A 4 bp insertion at ZmPLA1 encoding a putative phospholipase A generates haploid induction in maize. Mol Plant, 10, 520–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X. , Qin, Y. , Chen, B. , Liu, C. , Wang, L. , Li, X. , Dong, X. et al. (2018) Hetero‐fertilization together with failed egg–sperm cell fusion supports single fertilization involved in in vivo haploid induction in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 4689–4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. , Zhu, L. , Zhao, B. , Zhao, Y. , Xie, Y. , Zheng, Z. , Li, Y. et al. (2019) Development of a haploid‐inducer mediated genome editing (IMGE) system for accelerating maize breeding. Mol Plant, 12, 597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L. , Zhang, Y. , Liu, C. , Liu, Y. , Wang, Y. , Liang, D. , Liu, J. et al. (2018) OsMATL mutation induces haploid seed formation in indica rice. Nat Plants, 4, 530–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y. , Liu, C. , Qi, X. , Jiao, Y. , Wang, D. , Wang, Y. , Liu, Z. et al. (2019) Mutation of ZmDMP enhances haploid induction in maize. Nat Plants, 5, 575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]