Abstract

Objective

To determine if there are differences in opioid prescribing among generalist physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) to Medicare Part D beneficiaries.

Design

Serial cross-sectional analysis of prescription claims from 2013 to 2016 using publicly available data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Subjects

All generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs who provided more than 10 total prescription claims between 2013 and 2016 were included. These prescribers were subsetted as practicing in a primary care, urgent care, or hospital-based setting.

Methods

The main outcomes were total opioid claims and opioid claims as a proportion of all claims in patients treated by these prescribers in each of the three settings of interest. Binomial regression was used to generate marginal estimates to allow comparison of the volume of claims by these prescribers with adjustment for practice setting, gender, years of practice, median income of the ZIP code, state fixed effects, and relevant interaction terms.

Results

There were 36,999 generalist clinicians (physicians, NPs, and PAs) with at least one year of Part D prescription drug claims data between 2013 and 2016. The number of adjusted total opioid claims across these four years for physicians was 660 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 660–661), for NPs was 755 (95% CI = 753–757), and for PAs was 812 (95% CI = 811–814).

Conclusions

We find relatively high rates of opioid prescribing among NPs and PAs, especially at the upper margins. This suggests that well-designed interventions to improve the safety of NP and PA opioid prescribing, along with that of their physician colleagues, could be especially beneficial.

Keywords: Opioid Prescribing, Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistant, Primary Care

Introduction

The volume of opioid prescriptions in the United States has increased dramatically over the last two decades, and evidence suggests that this has perpetuated opioid misuse, addiction, overdose, and drug-related deaths [1,2]. It should be noted that the rate of death from natural and semisynthetic opioids (which includes commonly prescribed opioids like hydromorphone, hydrocodone, and oxycodone) has increased only mildly over the last five years, whereas deaths from synthetic opioids other than methadone (including tramadol, pharmaceutical fentanyl, illicitly produced fentanyl, and fentanyl derivatives) have increased markedly [3]. Specifically, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone increased by 45% between 2016 and 2017 [3]. It can be difficult to determine if an opioid-related death is due to a pharmaceutically or illicitly manufactured drug or if the medication was prescribed to the individual or diverted [4].

Over the last few years, there has been evidence of a mild reversal in the trend [2,5]. The most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report in July 2017 showed that opioid use peaked in 2010 at 782 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per capita and decreased to 640 MME per capita in 2015. However, this is still three times the rate in 1999 [5]. In 2016, the CDC issued guidelines for the use of opioids in chronic pain [6]. An analysis in 2018 showed that the decline in opioid prescribing accelerated after these guidelines, but a causal relationship could not be determined [7].

Previous work suggests that in the ambulatory setting, quality of care by physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) is equivalent [8]. Variation in medication prescribing among these three types of practitioners has not been extensively studied. To our knowledge, differences in opioid prescribing among generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs have not been evaluated.

The number of graduates from NP and PA training programs has increased recently [9], as has the number of NPs and PAs per full-time equivalent (FTE) physicians in certain generalist settings, including family medicine, multispecialty groups, and hospital medicine groups [10]. Based on projections in 2013, the primary care NP and PA workforce was projected to grow 58% and 30%, respectively, between 2010 and 2020, faster than the primary care physician supply [11]. Thus, differences in prescribing rates, particularly of opioids among generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs, are especially important.

We used publicly available data on Medicare Part D prescribers to evaluate opioid prescribing among generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs. Beneficiaries with Medicare have the option but are not required to choose a prescription drug insurance plan for an additional cost [12]. Currently, 71% of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare Part D plans [13]. We aimed to learn if there are differences in opioid prescribing among generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs to Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

Data Sources

We used the publicly available Medicare Part D Opioid Prescriber Summary Files for 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 [14]. These files include the National Provider Identification (NPI) number of every prescriber who wrote a prescription for a beneficiary with Medicare Part D insurance, as well as the prescriber’s full name, ZIP code of practice, state, specialty, total prescription claims, total opioid claims, and opioid prescribing rate. For NPs and PAs, the specialty field lists their classification (NP or PA) but not their clinical specialization. Data for prescribers having between one and 10 opioid or total prescription claims in a year were withheld. The Medicare Physician Compare National Downloadable File [15] provides information on each prescriber’s organization’s legal name, gender, and years in practice. These two data sets were merged by NPI number. Data on median income of residents by ZIP code were obtained from the United States Census Bureau [16] and were merged with the data set.

Population

We defined generalist physicians as those practicing internal medicine or family medicine, as labeled in the specialty field. We categorized practice environments as primary care, urgent care/walk-in clinic, and hospital medicine. Hospital medicine prescription claims represent only those written for Medicare Part D patients upon discharge from a hospital. Because neither the Opioid Prescriber Summary Files nor the Medicare Physician Compare File provides specialty information for NPs and PAs, we employed a string search strategy to identify generalist NPs and PAs and also to determine their practice environment using their organizations’ legal names.

String searches positive for “internal,” “family,” or “primary care” were categorized as primary care. String searches positive for “minuteclinic,” “urgent care,” and “immediate care” were categorized as urgent care/walk-in clinic. Those positive for “hospitalist” were classified as hospital medicine. This strategy was also used to categorize the practice environment of physicians, and only physicians with a positive string search were included in the analysis. Two organization legal names were utilized for string searches. Prescribers with two different practice settings defaulted to hospital medicine primarily and urgent care/walk-in clinic secondarily. However, fewer than 1% of physicians, NPs, and PAs were noted to practice in multiple settings. The accuracy of this search strategy was checked by performing a web-based search using the NPI number and full name to confirm practice setting on 0.5% of the practitioners in the analysis sample.

Analyses

Each prescriber’s total prescription claims and total opioid claims were calculated for the period of January 2013 through December 2016, as the Opioid Prescriber Summary Files only had claims on a yearly basis. Total prescription claim counts for 2013 through 2016 for a given provider excluded all prescription counts in years for which the opioid claim counts were withheld. The opioid claim proportion for each prescriber was generated as total opioid claims as a percentage of total prescription claims for the period of 2013 to 2016.

We summarized the crude opioid prescription proportions for each provider type in each practice setting (primary care, urgent care/walk-in clinic, hospital). We then used generalized linear regression models with a binomial distribution to estimate the total opioid prescription claims for each of the three prescriber types, controlling for practice setting, gender, years of practice (in 10-year increments), median income of the ZIP code (per quantiles), and potentially relevant interaction terms (Supplementary Data). State of practice was included as a fixed effect. These models were used to generate marginal estimates of the total opioids prescribed by generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs over the four-year period. The model was also run separately by year.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. One repeated the binomial regression on a subset of states that we inferred have few opioid-prescribing restrictions for NPs and PAs. This included all states in which 90% or more of the NPs and PAs prescribed opioids: Alaska, Arizona, Connecticut, Idaho, Maryland, Montana, North Dakota, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. The second sensitivity analysis replaced the opioid claim counts that had been withheld from public release with a count of five. Analyses were done using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

There were 36,999 generalist clinicians (physicians, NP, and PAs) with at least one year of Part D prescription claims data between 2013 and 2016 who could be classified as practicing in a primary care, urgent care, or hospital-based setting (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prescription claim counts

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate (N = 36,999) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 26,991 | 28,614 | 30,570 | 30,425 |

| Total claims | 32,486 | 34,358 | 36,438 | 36,345 |

| Practice location | ||||

| Primary care (N = 23,328) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 18,884 | 19,689 | 20,632 | 20,749 |

| Total claims | 21,360 | 22,218 | 23,123 | 23,116 |

| Urgent care (N = 7,758) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 4,421 | 4,963 | 5,676 | 5,491 |

| Total claims | 5,826 | 6,599 | 7,573 | 7,542 |

| Hospital-based (N = 5,913) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 3,686 | 3,962 | 4,262 | 4,185 |

| Total claims | 5,300 | 5,541 | 5,742 | 5,687 |

| Practitioner type | ||||

| Physician (N = 24,213) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 20,047 | 20,572 | 20,838 | 20,707 |

| Total claims | 23,342 | 23,745 | 23,970 | 23,918 |

| Nurse practitioner (N = 8,171) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 4,245 | 5,038 | 6,266 | 6,323 |

| Total claims | 5,556 | 6,599 | 7,943 | 7,900 |

| Physician assistant (N = 4,615) | ||||

| Opioid claims | 2,699 | 3,004 | 3,466 | 3395 |

| Total claims | 3,588 | 4,014 | 4,525 | 4,527 |

Withheld Data

Significantly more data were withheld from public release for low prescription counts for NPs and PAs than for physicians. The percentage of physicians in a year with withheld data ranged from 13.1% in 2015 to 14.1% in 2013. For NPs, it ranged from 20.0% in 2016 to 23.7% in 2014. For PAs, it ranged from 23.4% in 2015 to 25.2% in 2014.

Prescribers Providing No Opioids

There were 63 physicians, 552 NPs, and 105 PAs with no opioid claims by Medicare Part D beneficiaries (but a nonzero number of total prescription claims) in each of the four years studied. There were 1,859 physicians, 3,635 NPs, and 1,159 PAs who generated no opioid claims (but a nonzero number of total prescription claims) in at least one of the four years studied.

Prescription Claims by Practitioner Type

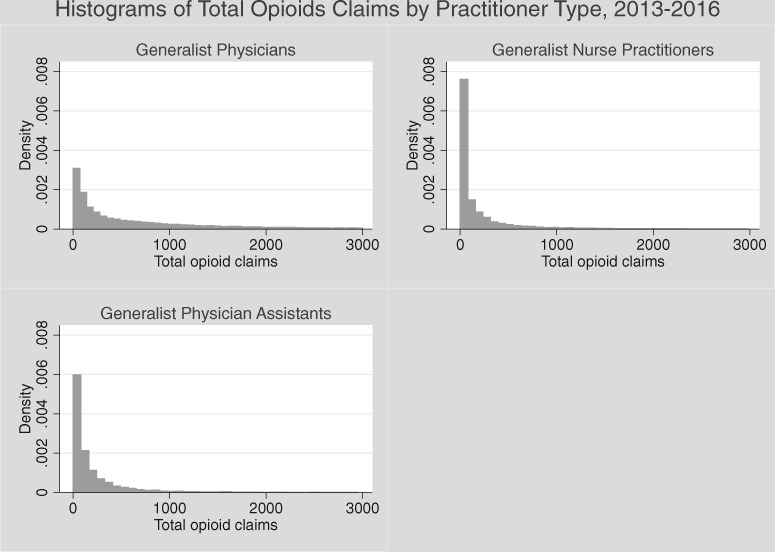

The distributions of total opioid claims for all thee practitioner types were extremely right-skewed but clustered around zero (Figure 1). The variation in opioid prescription proportions for PAs was higher than that of physicians and NPs in all three practice environments (Table 2). Opioid prescription proportions were lowest in primary care and hospital-based settings for physicians, but lowest in urgent care/walk-in clinics for NPs. The mean opioid prescription proportions (as a proportion of all prescription claims) for physicians in primary care, urgent care/walk-in clinics, and hospital medicine were 4.69, 6.72, and 6.66, relative to 7.10, 11.97, and 11.01 for PAs.

Figure 1.

Histogram of Total Opioid Claims by Practitioner Type, 2013–2016.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of opioid prescription proportion

| No. of Prescribers | Mean Opioid Rx Proportion | (SD) | Median | [Interquartile Range] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | |||||

| MD | 16,193 | 4.69 | (3.82) | 3.97 | [2.52 5.91] |

| NP | 4,372 | 5.26 | (8.28) | 3.16 | [0.53 6.17] |

| PA | 2,099 | 7.10 | (10.57) | 4.22 | [1.92 7.42] |

| Urgent care | |||||

| MD | 2,283 | 6.72 | (6.49) | 5.27 | [3.03 8.41] |

| NP | 2,906 | 4.82 | (9.73) | 0.00 | [0 5.43] |

| PA | 1,987 | 11.97 | (13.81) | 7.28 | [2.05 17.44] |

| Hospital medicine | |||||

| MD | 4,814 | 6.66 | (4.61) | 6.22 | [4.01 8.64] |

| NP | 447 | 8.06 | (11.31) | 4.57 | [0 10.48] |

| PA | 182 | 11.01 | (14.92) | 6.09 | [0 15.19] |

MD = doctor of medicine; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant.

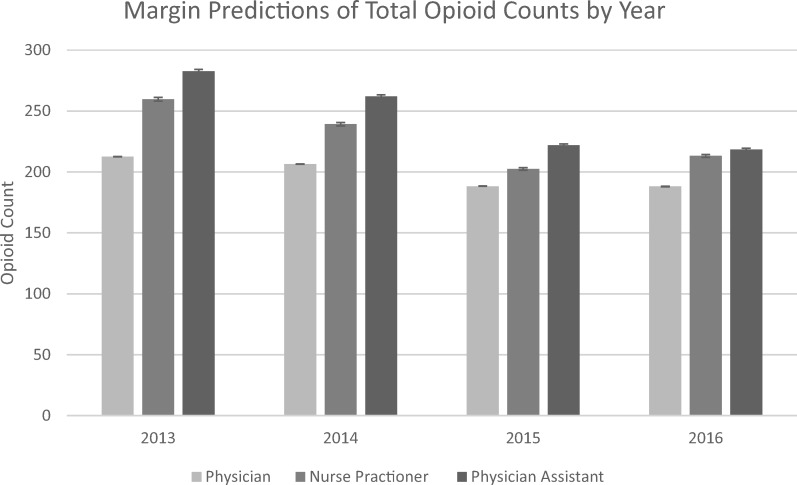

The adjusted total number of opioid claims across these four years was 660 for physicians (95% confidence interval [CI] = 660–661), 755 for NPs (95% CI = 753–757), and 812 for PAs (95% CI = 811–814). In the analysis by year, there was a decreasing trend in prescribing for each generalist type except for NPs between 2015 and 2016 (Figure 2). Also, physician opioid prescribing was stable between 2015 and 2016.

Figure 2.

Margin predictions of total opioid counts.

NPs and PAs made up a disproportionate number of the prescribers with the highest 5% of opioid prescription proportions. PAs made up 43% of this group and 12% of the entire study sample. NPs made up 32% of this group and 22% of the study sample. Physicians made up 24% of this group and 66% of the study sample. A disproportionate number of those with the highest 5% of opioid prescribing proportions worked in an urgent care setting. About 51% of this group was from the urgent care setting, whereas prescribers from this setting made up 20% of the study sample.

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis examining the subset of states with presumably fewer opioid prescribing restrictions for NPs and PAs yielded predictions of 543 (95% CI = 542–544) for physicians, 775 (95% CI = 771–780) for NPs, and 752 (95% CI = 748–757) for PAs. The sensitivity analysis replacing missing data yielded predictions of 638 (95% CI = 638–638) for physicians, 702 (95% CI = 700–704) for NPs, and 760 (95% CI = 758–762) for PAs (Supplementary Data).

Discussion

We compared opioid prescribing to Medicare Part D beneficiaries by generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs practicing in three different environments. Our identification strategy found 24,213 generalist physicians working in either primary care, urgent care, or hospital-based practice. There were 260,957 physicians practicing generalist medicine (internal medicine or family medicine) in the data set. This count is similar to the estimate of 225,000 active internal medicine and family medicine physicians described in the 2016 Physician Specialty Data Report by the American Association of Medical Colleges [17]. Our data set includes all physicians who were active in any of the years from 2013 to 2016, which may explain the small difference.

We found that the overall volume and proportion of opioid prescribing are heavily right-skewed. This is consistent with previous analyses of Medicare Part D opioid prescribing [18] and also of California workers’ compensation claims [19], which showed that 3% of physicians were responsible for 55% of all schedule II controlled substance prescriptions. We found that the mean numbers of opioid claims, as a proportion of all prescription claims, from NPs and PAs in the primary care and hospital-based settings are higher than that of physicians. This is likely driven by the highest prescribing 25% of NPs and PAs. Moreover, it is especially interesting given that the lowest quartile of NPs and PAs had lower proportions than physicians (Table 2). This may be attributable to state-specific restrictions. As of October 2017, Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia had limitations on opioid prescribing for NPs and/or PAs (Table 3) [20–22]. Current restrictions on opioid prescribing for NPs and PAs range from not allowing them to prescribe schedule II opioids at all to requiring additional training or limiting the supply of opioids they can provide. However, over the last two decades, states have been increasing the scope of practice of NPs and PAs and decreasing prescribing limitations [23,24]. For example, between 2001 and 2010, three states (Hawaii, Kentucky, and Virginia) changed from not allowing NPs to prescribe any controlled substances to allowing them to prescribe schedules II through V [24].

Table 3.

Independence of NPs and PAs by state, as of 2017

| States with full independent practice authority for NPs | Alaska, Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington DC, Washington State, Wyoming |

| States with full independent practice authority for PAs | Alaska, Illinois – subject to “Collaborative Agreement” with physicians rather than supervised by physicians |

| New Mexico – requires supervision for PAs with fewer than 3 years of clinical experience and for PAs practicing specialty medicine | |

| States with limitations on opioid prescribing for NPs and PAs | Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, West Virginia |

NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant.

The marginal predictions show that overall opioid prescribing by physicians, NPs, and PAs decreased from 2013 to 2016. This may be the result of increased awareness of the adverse effects of overuse of opioids and the concomitant efforts of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to crack down on high-volume opioid prescribing [25,26]. This may also be due in part to the CDC guidelines on using opioids to treat chronic pain issued in 2016 [6]. Moreover, the decrease in NP and PA prescribing was more marked, and this narrowed the differential among prescriber types. The subgroup analysis of states with more liberal NP and PA prescribing laws had fewer opioid prescriptions overall but a larger disparity among provider types. Notably, this analysis excluded states with the most opioid prescribing [27], specifically Nevada, Florida, Kentucky, and West Virginia.

Previous work has examined aggregate opioid prescribing of NPs and PAs and compared it with that of various medical specialties [18,28–30]. These studies analyzed NPs and PAs of all specialties as one group. However, these results are difficult to interpret because there is enormous variation in opioid prescribing rates of physicians among different specialties [29]. For example, orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons prescribe opioids at a higher rate than internists. One would expect trends to be relatively similar for NPs and PAs in these specialties. Thus, it makes more sense to evaluate NP and PA prescribing at a specialty level rather than in aggregate. An examination of opioid prescribing in Oregon using its prescription drug monitoring program found that NPs provided more high-risk opioid prescriptions than physicians and PAs [28]. However, this was thought to be due to patients at high risk for opioid misuse being more likely to seek out NPs.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare opioid prescribing patterns of generalist NPs and PAs with those of generalist physicians. This is an important area of inquiry, as primary care physicians make up the plurality of all physicians. A study of prescribers associated with fatalities in Utah showed that primary care providers were the most frequent opioid prescribers and also the most frequent prescribers of opioids leading to fatalities [31]. The overall proportion of opioid claims among all prescription claims for primary care physicians in our sample is roughly 5%, which is consistent with previous research [29]. We find that NPs and PAs prescribe a disproportionately high quantity of opioids to Medicare beneficiaries with Part D coverage. Of course, we do not know if the patients seen by generalist physicians, NPs, and PAs are similar with regard to need for opioids. We do not know of any large-scale national studies comparing the medical complexity or acuity of patients seen by physicians with those seen by NPs or PAs in generalist settings. However, it is important to acknowledge that NPs and PAs may be serving different roles than physicians in these three settings. For example, NPs and PAs in primary care may be more likely to see the urgent visits as opposed to the follow-up visits, which may be more likely to be for acute pain. Additionally, NPs and PAs may be responsible for managing routine medication refill visits in the primary care setting, which could lead to a disproportionate number of opioid prescriptions attributed to them.

There are a number of potential explanations for these prescribing differences that could not be tested with our data. One is that pharmaceutical companies may be targeting and aggressively marketing the prescription of opioids to NPs and PAs. In fact, recent evidence suggests that Purdue Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures and sells a number of opioids, did intentionally target NPs and PAs practicing general medicine [32,33]. Alternatively, NPs and PAs who have recently trained or practiced in a surgical subspecialty environment, where higher rates of opioids are typically prescribed, may bring those prescribing tendencies to a general medicine environment when they change specialties.

Limitations

One limitation of this work is that the data set does not provide information on the size of opioid claims. In other words, a prescription claim for a large supply of opiates is treated identically to a claim for a small supply. Another limitation is that we examined only prescriptions filled by beneficiaries with Medicare Part D. Thus, our results may not be generalizable regarding opioid prescribing to the population under age 65 years or to older patients in managed care Medicare plans. Previous research [34] has suggested a relationship between prescription of opioids during primary care visits and type of insurance, but there have been no studies showing a causal effect between insurance status and receipt of opioid prescriptions.

Additionally, we only included in the analysis prescribers who were identifiable as generalists by their organizations’ legal names. Thus, many prescribers were not included, and there is some risk of misclassification. However, we did perform a check on the string search strategy, which showed it to be accurate. A minor limitation is that our data include opioid prescription proportions from 2013 to 2016, but they do not include physicians, NPs, and PAs who started practicing in 2016, as these data are not yet available. Finally, the scope of practice for NPs and PAs, including the ability to independently prescribe opioids, has changed over the last decade [24]. Overall, the scope of practice has expanded for NPs and PAs. We did not evaluate specific changes in state-level legislation related to NP and PA opioid prescribing privileges throughout this period, though we did control for state fixed effects and also performed a sensitivity analysis on a subset of states.

Conclusions

Our findings have important policy implications. There is a widely held belief that high opioid prescribing by physicians is a driver of the opioid epidemic. The finding of higher opioid prescribing by NPs and PAs suggests that a well-crafted intervention to improve the safety of NP and PA opioid prescribing at least equal to that required of physicians could be useful to help curb opioid misuse, addiction, and diversion.

There are a number of policy solutions that could help ameliorate this prescribing disparity. The accreditation and licensing organizations for NPs and PAs could utilize continued education requirements to ensure that clinicians are knowledgeable about opioid prescribing guidelines and best practices and also how to screen for opioid misuse. Such requirements would also be beneficial for physicians, and some states have already initiated them [35]. It may be helpful if the CMS and DEA provided prescribing data stratified by clinician type (physician, NP, PA) and practice setting to help identify prescribing patterns among individual prescribers and group practices. In January 2018, the DEA announced that it would “surge” resources to identify prescribers and pharmacies with outlier opioid prescribing behaviors [36]. We must all recognize that being an outlier may not account for unique practice settings, individualized patient phenotypes, and other factors. Finally, all prescribing clinicians and those who dispense opioids should work together as a team to ensure they are appropriately up to date on pain therapeutics, including applicable initial and ongoing risk assessment, variable nonopioid medication, and nonmedication alternatives. Physicians, NPs, and PAs share an equal and corresponding responsibility to ensure that they are compliant and competent with all regulations and are providing the safest available options for patients.

This analysis suggests that resources specifically targeted to helping NPs and PAs could be especially effective at reducing opioid prescribing. Further research should evaluate whether high-volume opioid prescribing NPs and PAs tend to be associated with specific organizations with high-volume opioid prescribing physicians and whether there is an association between high-volume opioid prescribing and other low-value or high-risk health care practices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nayoung Rim, PhD, and Jiangxia Wang, MS, MA, for technical assistance.

Funding sources: We would like to acknowledge support for the statistical analysis from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health through grant number 1UL1TR001079. Dr. Segal is supported by the National Institute on Aging, grant K24AG049036.

Disclaimer: The funding source had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the National Institute on Aging.

Conflicts of interest: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1. Calcaterra S, Glanz J, Binswanger IA.. National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999-2009. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(3):263–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015;372(3):241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief, No 329. Hyattsville, MD; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seth P, Rudd RA, Noonan RK, Haegerich TM.. Quantifying the epidemic of prescription opioid overdose deaths. Am J Public Health 2018;108(4):500–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(26):697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA 2016;315(15):1624–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bohnert ASB, Guy GP, Losby JL.. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 opioid guideline. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(6):367–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurtzman ET, Barnow BS.. A comparison of nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and primary care physicians’ patterns of practice and quality of care in health centers. Med Care 2017;55(6):615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salsberg E. The nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and pharmacist pipelines: Continued growth. Health Affairs Blog. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organization is the Medical Group Management Association. The rising trend of nonphysician provider utilization in healthcare: A follow up to the 2014. MGMA research & analysis report. Available at: https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/about_acp/chapters/ga/rising_trend_of_nonphysicianprovider_utilization_in_healthcare_2017.pdf. (accessed March 1, 2018).

- 11.Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions, National Center for Health Workforce. Projecting the supply and demand for primary care practitioners through 2020. Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions, National Center for Health Workforce analysis. 2013. Available at: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projectingprimarycare.pdf. (accessed March 18, 2018).

- 12.Medicare.gov. Medicare drug coverage (Part D) 2018. Available at: https://www.medicare.gov/part-d/ (accessed June 26, 2018).

- 13. Hoadley J, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Medicare Part D in 2016 and trends over time. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016. Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicare-part-d-in-2016-and-trends-over-time-section-1-part-d-enrollment-and-plan-availability/ (accessed April 28, 2018).

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D opioid prescriber summary file (2018). Available at: https://data.cms.gov/browse? tags=opioidmap (accessed February 23, 2018).

- 15.Medicare.gov. Physician compare national downloadable file. 2018. Available at: https://data.medicare.gov/data/physician-compare (accessed February 23, 2018).

- 16.Census.gov. American Fact Finder – 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. 2017. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/ (accessed March 21, 2018).

- 17.AAMC. 2016 physician specialty data report by the AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html. (accessed February 17, 2018).

- 18. Chen JH, Humphreys K, Shah NH, Lembke A.. Distribution of opioids by different types of Medicare prescribers. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(2):259–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swedlow A, Ireland J, Johnson G. Prescribing Patterns of Schedule II Opioids in California Workers’ Compensation – Research Update. Oakland: California Workers' Compensation Institute; 2011.

- 20.US DOJ. Mid-level practitioners authorization by state. 2017. Available at: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/practioners/index.html (accessed February 21, 2018).

- 21.Scope of Practice Policy - Collaboration between the National Conference of State Legislatures and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. 2019. Available at: http://scopeofpracticepolicy.org/practitioners/nurse-practitioners/ (accessed October 22, 2018).

- 22.AMA Advocacy Resource Center. Physician assistant scope of practice. 2018. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/arc-public/state-law-physician-assistant-scope-practice.pdf (accessed October 22, 2018).

- 23.Scope of practice: How can we expand access to care? – A Politico Pro Health Working Group report. Politico. 2016. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/scope-of-practice-health-care-224571 (accessed March 3, 2018).

- 24. Gadbois EA, Miller EA, Tyler D, Intrator O.. Trends in state regulation of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, 2001 to 2010. Med Care Res Rev 2015;72(2):200–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DEA. DEA surge in drug diversion investigations leads to 28 arrests and 147 revoked registrations; surge part of administration’s focus on combatting the opioid epidemic. 2018. Available at: https://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2018/hq040218.shtml (accessed March 25, 2018).

- 26. Hoffman J. Medicare is cracking down on opioids. Doctors fear pain patients will suffer. The New York Times. March 27, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/27/health/opioids-medicare-limits.html. (accessed May 20, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izrael D.. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the U.S. J Pain 2012;13(10):988–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fink PB, Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, Hildebran C.. Opioid prescribing patterns and patient outcomes by prescriber type in the Oregon prescription drug monitoring program. Pain Med 2018;19(12):2481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM.. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(3):409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lev R, Lee O, Petro S, et al. Who is prescribing controlled medications to patients who die of prescription drug abuse? Am J Emerg Med 2016;34(1):30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Porucznik CA, Johnson EM, Rolfs RT, Sauer BC.. Specialty of prescribers associated with prescription opioid fatalities in Utah, 2002-2010. Pain Med 2014;15(1):73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Washington Stage Attorney General’s Office. New details unsealed in lawsuit against one of the nation’s largest opioid manufacturers – statement by Washington Stage Attorney General’s Office. 2018. Available at: http://www.atg.wa.gov/news/news-releases/ferguson-new-details-unsealed-lawsuit-against-one-nation-s-largest-opioid (accessed April 4, 2018).

- 33.Christopher S. Porrino, Attorney General of the State of New Jersey. Complaint for violation of the New Jersey False Claims Act. 2017. Available at: http://nj.gov/oag/newsreleases17/NJ-Purdue-Complaint_Redacted_final.pdf (accessed April 1, 2018).

- 34. Olsen Y, Daumit GL, Ford DE.. Opioid prescriptions by U.S. primary care physicians from 1992 to 2001. J Pain 2006;7(4):225–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Federation of State Medical Boards. Continuing medical education; board-by-board overview. 2018. Available at: http://www.fsmb.org/globalassets/advocacy/key-issues/continuing-medical-education-by-state.pdf (accessed October 22, 2018).

- 36.Justice.gov. Attorney General Sessions delivers remarks on efforts to reduce violent crime and fight the opioid crisis. 2018. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-sessions-delivers-remarks-efforts-reduce-violent-crime-and-fight-opioid (accessed May 3, 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.