Summary

The extent to which behavior is shaped by experience varies between individuals. Genetic differences contribute to this variation, but the neural mechanisms are not understood. Here, we dissect natural variation in the behavioral flexibility of two Caenorhabditis elegans wild strains. In one strain, a memory of exposure to 21% O2 suppresses CO2-evoked locomotory arousal; in the other, CO2 evokes arousal regardless of previous O2 experience. We map that variation to a polymorphic dendritic scaffold protein, ARCP-1, expressed in sensory neurons. ARCP-1 binds the Ca2+-dependent phosphodiesterase PDE-1 and co-localizes PDE-1 with molecular sensors for CO2 at dendritic ends. Reducing ARCP-1 or PDE-1 activity promotes CO2 escape by altering neuropeptide expression in the BAG CO2 sensors. Variation in ARCP-1 alters behavioral plasticity in multiple paradigms. Our findings are reminiscent of genetic accommodation, an evolutionary process by which phenotypic flexibility in response to environmental variation is reset by genetic change.

Keywords: experience-dependent plasticity; natural variation; neuropeptide; genetic accommodation; Caenorhabditis elegans, carbon dioxide sensing; oxygen sensing

Highlights

-

•

Behavioral flexibility varies across Caenorhabditis and C. elegans wild isolates

-

•

A natural polymorphism in ARCP-1 underpins inter-individual variation in plasticity

-

•

ARCP-1 is a dendritic scaffold protein localizing cGMP signaling machinery to cilia

-

•

Disrupting ARCP-1 alters behavioral plasticity by changing neuropeptide expression

Individuals can vary in their capacity to adapt their behavior to changes in the environment. Beets et al. identify a natural genetic polymorphism that modifies behavioral flexibility by altering the neuromodulatory output of primary sensory neurons.

Introduction

Animals reconfigure their behavior and physiology in response to experience, and many studies highlight mechanisms underlying such plasticity (Bargmann, 2012, Owen and Brenner, 2012). While plasticity is presumed crucial for evolutionary success, it has costs and often varies across species and between individuals (Coppens et al., 2010, Dewitt et al., 1998, Mery, 2013, Niemelä et al., 2013). Variation in behavioral flexibility is thought to underlie inter-individual differences in cognitive ability and capacity to cope with environmental challenges (Coppens et al., 2010, Niemelä et al., 2013). The genetic and cellular basis of inter-individual variation in experience-dependent plasticity is, however, poorly understood.

Genetic accommodation and assimilation are concepts used to describe variation in plasticity on an evolutionary timescale. Waddington and Schmalhausen suggested genetic assimilation occurs when a phenotype initially responsive to the environment becomes fixed in a specific state (Renn and Schumer, 2013, Schmalhausen, 1949, Waddington, 1942, Waddington, 1953). This loss of plasticity may reflect genetic drift or selection against the costs of expressing adaptive behaviors (Niemelä et al., 2013). Studies of genetic assimilation led to the broader concept of genetic accommodation, referring to evolutionary genetic variation leading to any change in the environmental regulation of a phenotype (Crispo, 2007, West-Eberhard, 2005). Many studies in insects, fish, rodents, and primates highlight inter-individual variation in behavioral plasticity; in some cases this has been shown to be heritable (Dingemanse and Wolf, 2013, Izquierdo et al., 2007, Mery et al., 2007), but the mechanisms responsible for these differences remain enigmatic.

Many animals use gradients of respiratory gases to help locate prey, mates, or predators and have evolved sophisticated behavioral responses to environmental changes in oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels (Carrillo and Hallem, 2015, Cummins et al., 2014, Guerenstein and Hildebrand, 2008, Prabhakar and Semenza, 2015). Where studied, behavioral responses to CO2 have been shown to depend on environmental context, past experience, and life stage (Carrillo et al., 2013, Fenk and de Bono, 2017, Guillermin et al., 2017, Hallem and Sternberg, 2008, Sachse et al., 2007, Vulesevic et al., 2006). This flexibility makes CO2-sensing an attractive paradigm to study natural variation in behavioral plasticity.

CO2 responses in Caenorhabditis elegans are sculpted by previous O2 experience (Carrillo et al., 2013, Fenk and de Bono, 2017, Kodama-Namba et al., 2013). Acclimation to surface O2 levels (i.e., 21%) generates a memory that suppresses aversion of high CO2. The O2 memory is written over hours by O2 sensors, called URX, AQR, and PQR, whose activity is tonically stimulated by 21% O2 (Busch et al., 2012, Fenk and de Bono, 2017). 21% O2 is itself aversive to C. elegans, most likely because it signals surface exposure (Gray et al., 2004, Persson et al., 2009). By suppressing CO2 aversiveness, C. elegans acclimated to 21% O2 may increase their chance of escaping the surface into buried environments with elevated CO2 (Fenk and de Bono, 2017).

Here, we show that the impact of O2 experience on CO2 aversion varies across Caenorhabditis species and between wild C. elegans isolates. By characterizing differences between C. elegans isolates, we identify a polymorphism in a dendritic ankyrin-repeat scaffold protein, ARCP-1, that alters plasticity in one strain. ARCP-1 biochemically interacts with the conserved cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase PDE-1 and localizes it with molecular sensors for CO2 to the dendritic ends of BAG sensory neurons. Disrupting ARCP-1 resets CO2 sensitivity and experience-dependent plasticity of CO2 escape, in part by altering neuropeptide expression and conferring strong aversion to CO2.

Results

Natural Variation in Experience-Dependent Plasticity in Caenorhabditis

In C. elegans, a memory of recent O2 levels reprograms aversive responses to CO2 (Fenk and de Bono, 2017). We hypothesized this experience-dependent plasticity is evolutionarily variable. To investigate this, we compared the CO2 responses of different Caenorhabditis species grown at 21% or 7% O2 (Figure S1A). Animals were transferred to a thin bacterial lawn in a microfluidic chamber kept at 7% O2, stimulated with 3% CO2, and their behavioral responses quantified. We used a background level of 7% O2 in all assays because C. elegans dwell locally at this O2 concentration, making locomotory arousal by CO2 prominent. By contrast, 21% O2 evokes sustained rapid movement, making CO2 responses above this high baseline proportionally small. As a representative C. elegans strain, we used LSJ1, a wild-type (N2-like) laboratory strain bearing natural alleles of the neuropeptide receptor npr-1(215F) and the neuroglobin glb-5(Haw). We did not use the standard N2 strain, because it has acquired mutations in npr-1 and glb-5 that confer gas-sensing defects (McGrath et al., 2009, Persson et al., 2009). As expected, C. elegans was aroused more strongly by CO2 when acclimated to 7% O2 (Figure S1B). By contrast, O2 experience did not alter the absolute speed of representative strains of C. latens and C. angaria at 3% CO2 (Figure S1B). Because C. angaria was not aroused by 3% CO2, we tested its response to 5% and 10% CO2. These levels evoked locomotory arousal that, as in C. elegans, was stronger in animals acclimated to 7% O2 (Figure S1C). Thus, C. angaria is less sensitive to CO2 than C. elegans, but its arousal by CO2 remains dependent on O2 experience. By contrast, CO2 responses of C. latens were unaffected by previous O2 experience at any concentration tested (Figure S1D). Unexpectedly, acclimation to 7% O2 suppressed rather than enhanced the locomotory response of C. nigoni to CO2 (Figure S1B). Thus, the effect of O2 memory on CO2-evoked behavioral responses is evolutionarily variable.

Effect of O2 Memory on CO2 Responses Varies between C. elegans Wild Isolates

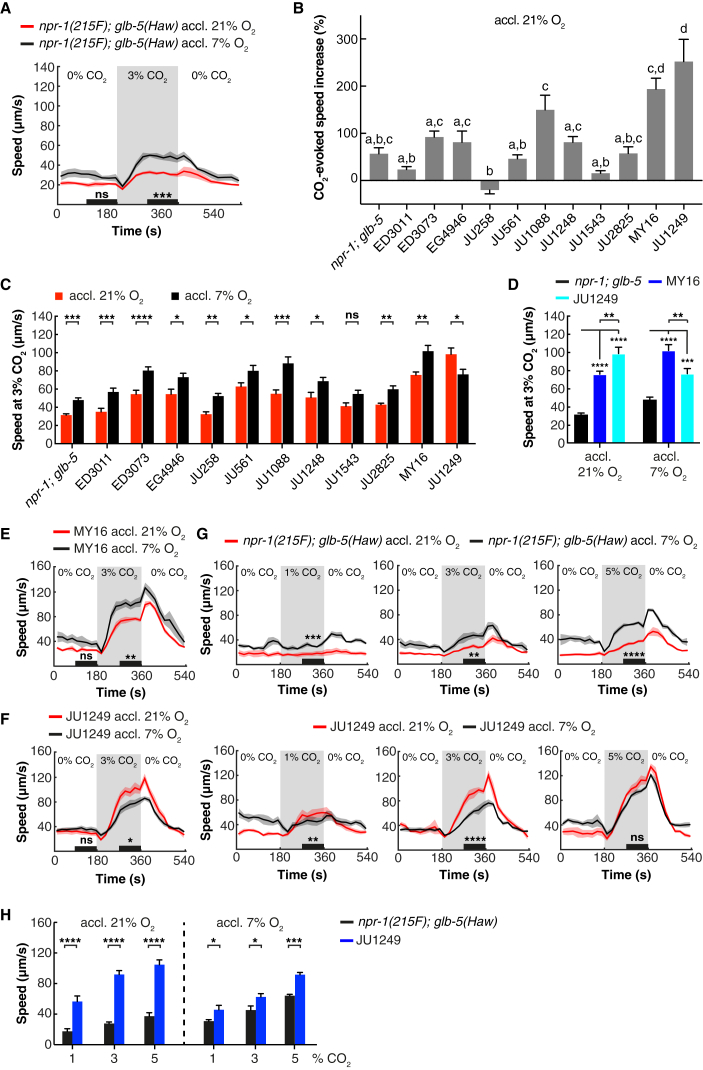

Our findings prompted us to seek intra-species variation in how O2 experience influences CO2 responses, by studying a genetically diverse collection of wild C. elegans isolates (Figure S2A). Most strains responded like the reference strain (Figures 1A–1C and S2A). However, two isolates, the French JU1249 and German MY16 strains, responded more strongly than other isolates to a rise in CO2 regardless of O2 experience (Figures 1B and 1D). For MY16 CO2 aversion was stronger when animals were acclimated to 7% O2, recapitulating the cross-modulation of CO2 responses observed in most strains (Figures 1C and 1E). By contrast, JU1249 animals acclimated to 21% O2 further enhanced rather than suppressed CO2 escape (Figures 1C and 1F). To probe further if the O2-dependent plasticity of CO2 escape had changed in JU1249, we quantified escape responses at different CO2 concentrations. npr-1; glb-5 control animals always responded more strongly to CO2 when acclimated to 7% O2, but this was not the case for JU1249 at any CO2 concentration tested (Figure 1G). CO-evoked arousal was stronger in JU1249 animals acclimated to 21% O2 than in those acclimated to 7% O2 (Figure 1H), suggesting that JU1249 fails to suppress CO2 escape at 21% O2.

Figure 1.

Natural Variation in the Regulation of CO2 Escape by Previous O2 Experience

(A) A C. elegans reference strain is more strongly aroused by CO2 when acclimated to 7% rather than 21% O2. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test; n = 6 assays. In this, and all subsequent figures, the background O2 level in the assay is 7%.

(B) Natural variation in the CO2 response of C. elegans wild isolates acclimated to 21% O2. Bars represent average increase in speed ± SEM when CO2 rises from 0% to 3%. The CO2-evoked speed increase is significantly different (p < 0.05) between isolates labeled with different letters (a–d). One-way ANOVA with Tukey test; n = 6 assays.

(C) The effect of O2 memory on CO2 responses in wild C. elegans isolates. Bars show mean ± SEM for time intervals indicated in (A) and Figure S2A. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test; n = 6 assays.

(D) JU1249 and MY16 are more strongly aroused by CO2, regardless of previous O2 experience. Bars plot mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey test; n = 6 assays.

(E and F) CO2 responses of MY16 (E) and JU1249 (F) animals acclimated to 21% or 7% O2. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test; n = 6 assays.

(G) Acclimation to 21% O2 in JU1249, unlike the reference strain LSJ1, enhances rather than suppresses locomotory arousal at different CO2 concentrations. n = 30–61 animals for npr-1; glb-5, n = 59–66 animals for JU1249. Mann-Whitney U test.

(H) CO2 arousal is increased more strongly in JU1249 animals acclimated to 21% rather than 7% O2. Bars plot mean ± SEM for time intervals indicated in (G). Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test. n = 4 assays.

For (A), (E), and (F), solid lines plot mean and shaded areas show SEM. Black bars indicate time intervals used for statistical comparisons. For (A)–(H), 20–30 animals were assayed in at least 4 trials for each condition. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

The increased locomotory arousal of JU1249 and MY16 in response to CO2 could reflect reduced inhibitory input from the neural circuit signaling 21% O2. To probe this, we asked if these isolates show altered behavioral responses to 21% O2. All isolates we tested responded similarly when we switched O2 from 7% to 21% (Figure S2B), suggesting they retained a functional O2-sensing circuit.

In our assays, we exposed animals acclimated to 21% O2 to a downshift to 7% O2 3 min before the CO2 stimulus. To ask if this drop in O2, rather than O2 experience, altered the CO2 response in JU1249, we extended the time animals spent at 7% O2 prior to receiving the CO2 stimulus to 24 min. JU1249 was still more strongly aroused by CO2 when acclimated to 21% rather than 7% O2; as expected, O2 experience had the opposite effect on plasticity in npr-1; glb-5 controls (Figure S2C). We also compared the behavioral responses of JU1249 and npr-1; glb-5 animals to a 21% to 7% O2 stimulus and found no significant differences (Figure S2D). Thus, the ability of an O2 memory to modify CO2 escape appears to be altered in JU1249, recapitulating the phenotype observed in C. nigoni.

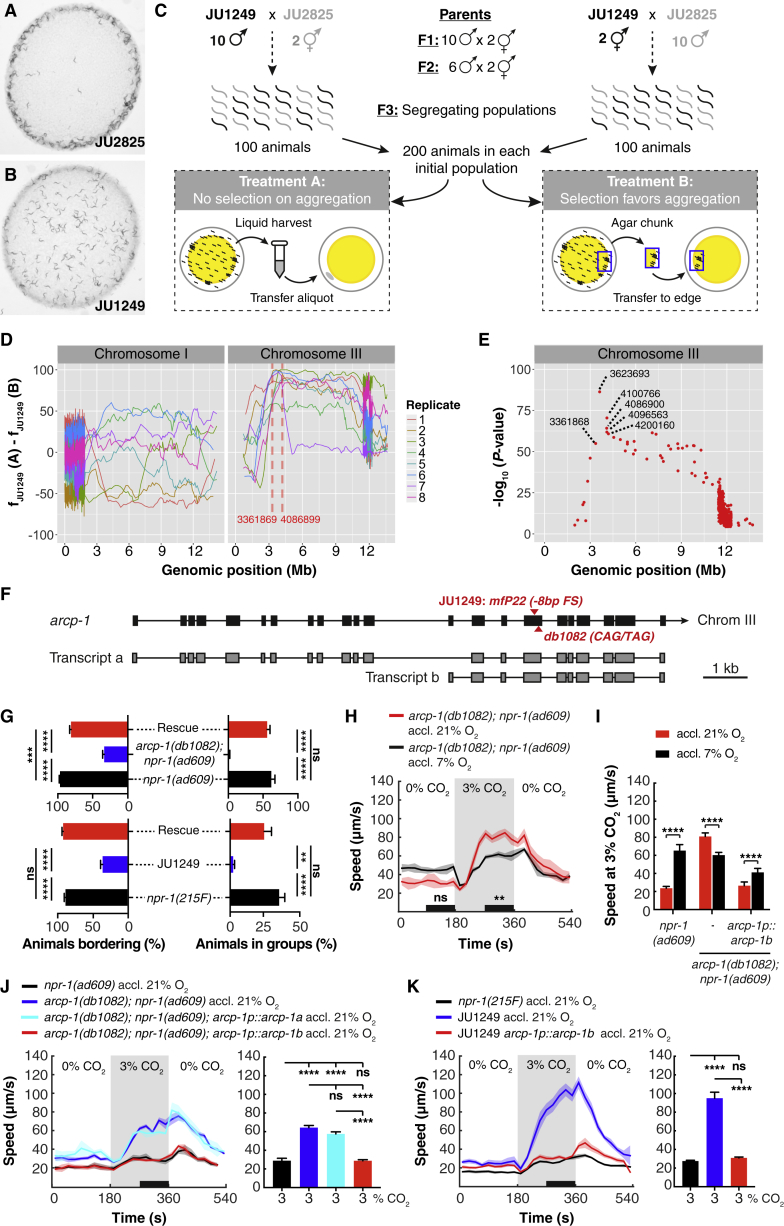

Natural Variation in the Ankyrin Repeat Protein ARCP-1 Alters Plasticity of CO2 Responses

We sought the genetic changes conferring altered plasticity of CO2 responses in JU1249. Besides altering this phenotype, JU1249 exhibited reduced aggregation and bordering behavior on an E. coli food lawn compared to other C. elegans wild isolates (Figures 2A and 2B). We speculated JU1249 aggregated poorly because increased avoidance of CO2 shifted the balance between attraction and repulsion as aerobic animals come together. In this model, the aggregation phenotype, which is easy to score, is linked to altered JU1249 CO2 responses.

Figure 2.

Natural Variation in ARCP-1 Alters CO2 Responses

(A and B) Individuals of JU2825, like most C. elegans wild isolates, aggregate at the border of an E. coli lawn (A). By contrast, JU1249 animals disperse across the lawn (B).

(C) Selection-based QTL mapping approach to establish the genetic basis of solitary behavior in JU1249.

(D) Line plots showing differences in JU1249 allele frequencies between treatment A and B for each replicate pair, using a sliding window 5 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) wide and a step size of one SNP. Replicates are indicated by different colors. Chromosome I shows little consistent deviations from equal frequencies in the two treatments, whereas chromosome III shows a strong enrichment at the 3–4 Mb interval.

(E) Read-count frequency differences between treatment A and B analyzed for consistency across eight replicates using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Only chromosome III is shown. p values are shown as –log10 (p value) adjusted by the Bonferroni correction.

(F) Gene structure of arcp-1 (F34D10.6). Boxes represent exons and lines indicate introns. The wild isolate JU1249 has an 8 bp deletion that introduces a frameshift. The db1082 allele, isolated in a genetic screen for aggregation-defective mutants, replaces a Gln codon with a premature stop codon.

(G) Wild-type arcp-1b rescues bordering and aggregation phenotypes of JU1249 and db1082 animals. For each assay, 50–60 animals were transferred to a bacterial lawn and behaviors were scored after 6 h. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test. n ≥ 6 assays.

(H) arcp-1(db1082) animals, like JU1249, fail to suppress CO2 responses when acclimated to 21% O2. n = 5–6 assays. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test.

(I) Expressing wild-type arcp-1 restores the O2-dependent modulation of CO2 responses in arcp-1; npr-1 mutants. n = 67–105 animals. Mann-Whitney U test.

(J) An arcp-1b transgene, but not arcp-1a, rescues the enhanced locomotory arousal evoked by CO2 in arcp-1; npr-1 animals acclimated to 21% O2. n ≥ 4 assays for all genotypes. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test.

(K) An arcp-1b transgene rescues the enhanced CO2 response of JU1249 animals acclimated to 21% O2. n = 6 assays. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test.

For (H)–(K), each genotype was tested in at least 4 assays with 20–30 animals per trial. Solid lines plot mean; shaded areas show SEM; horizontal black bars indicate time intervals for statistical comparisons; vertical bars plot mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

See also Figures S3, S4, and S5 and Data S1 and S2.

Before testing this hypothesis, we ruled out the possibility that JU1249 is genetically contaminated by the non-aggregating N2 lab strain, by genotyping the npr-1, glb-5, and nath-10 loci, which have acquired polymorphisms during N2 domestication (Duveau and Félix, 2012, McGrath et al., 2009, Persson et al., 2009, Weber et al., 2010). JU1249 exhibited the natural alleles found in other wild isolates at all three loci (Figure S3).

To map the JU1249 aggregation defect, we used a selection-based quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping approach in which we crossed JU1249 to the aggregating C. elegans wild isolate JU2825 (Figure 2A). To find conditions for selection-based QTL mapping, we first defined two treatments that differentially selected for aggregating and solitary animals and performed competition tests between JU1249 and JU2825 under these treatments. Starting with a 50:50% mix of each strain, JU1249 (solitary) outcompeted JU2825 (aggregating) when the populations were transferred by liquid harvest and aliquot (Figure S4A, treatment A), indicating that JU1249 has higher fitness in these conditions than JU2825. When cultivated by transferring an agar chunk from the border of the food lawn, where aggregating animals accumulate (Figure S4A, treatment B), JU2825 outcompeted JU1249, which indicates the aggregation trait in C. elegans is selectable. We used treatments A and B as selection regimes on populations of cross-progenies of JU1249 and JU2825 (Figure 2C), sequenced their genomes, and compared allele frequencies of paired replicate populations under the two treatments (Data S1; STAR Methods). Populations selected for aggregation (treatment B) were expected to have higher frequencies of JU2825 alleles at the QTL that affect the variation in aggregation behavior compared to the paired populations (treatment A). Our analysis showed large variation in allele frequencies among replicates, suggesting founder effects due to the moderate population sizes in the first crosses (Figures 2D and S4B). We used two criteria to identify candidate QTL regions associated with the aggregation phenotype. First, we identified regions that show consistent differences in allele frequencies among all replicate pairs for the two treatments (Figures S4B and S4C). Second, we narrowed down these regions by examining replicates for the position of the closest recombination event that was selected (Figure S4D). Based on these criteria, we identified a genomic interval on chromosome III (3361869–4086899 bp) as a candidate region, showing a highly significant difference in allele frequencies among the eight population pairs (Figures 2E and S4C).

The 725 kb QTL region in JU1249 contained 3 polymorphisms in protein-coding genes compared to N2 and JU2825 (Data S1J). An 8 bp deletion (mfP22) in the open reading frame of the gene F34D10.6, which we named arcp-1 (for ankyrin repeat containing protein, see below), stood out as a promising candidate for two reasons. First, mfP22 is the only polymorphism predicted to abolish protein function (Data S1J and S1K), introducing a frameshift and premature stop codon in both transcripts of the arcp-1 gene (Figures 2F and S5A). Second, we independently found several alleles of arcp-1 in a collection of sequenced mutants that suppress aggregation behavior of npr-1(null) animals, including two that introduced premature stop codons. The number and kind of these alleles made it likely that disrupting arcp-1 caused an aggregation defect. Consistent with this hypothesis, the aggregation defect of one strain (db1082 allele) mapped to a 1 Mb interval on chromosome III, centered on arcp-1 (Figures 2F and S5A). Two mutants from the million mutation project (Thompson et al., 2013), harboring arcp-1 alleles (gk856856 and gk863317) that introduce premature stop codons, were also defective in aggregation and bordering (Figures S5B and S5C). To show conclusively that mutations in arcp-1 disrupt aggregation, we performed transgenic rescue experiments. Expressing wild-type arcp-1 in JU1249 or in arcp-1(db1082); npr-1(null) mutants restored aggregation and bordering behavior (Figure 2G).

To gain insight into the distribution of the arcp-1(mfP22) polymorphism in C. elegans, we examined other wild isolates. Our analysis suggests mfP22 is a rare allele, because we did not find it in a set of 151 worldwide C. elegans isolates, including MY16 (Data S2).

Does disrupting arcp-1 alter responses to CO2? arcp-1(db1082); npr-1(null) animals behaved like JU1249: they showed no overt defect in their response to a 21%-to-7% O2 downshift (Figure S5D) but failed to suppress escape from different CO2 concentrations when acclimated to 21% O2 (Figures 2H, S5E, and S5F). A wild-type arcp-1 transgene rescued this CO2 plasticity defect (Figure 2I). arcp-1 is thus required for animals acclimated to 21% O2 to suppress escape from high CO2 environments.

Gene predictions and cDNA cloning revealed arcp-1a and arcp-1b transcripts that overlap at their 3′ end (Figure 2F; Wormbase WS265). The db1082 and mfP22 alleles affect both arcp-1 transcripts (Figure 2F). Expressing arcp-1b fully rescued the heightened CO2 response of these animals, whereas a transgene for the longer arcp-1a transcript did not (Figures 2J and 2K). A mutation that only disrupted arcp-1a also failed to recapitulate the enhanced CO2 response and aggregation phenotype of mutants defective in both arcp-1 transcripts (Figures S5C and S5G). Thus arcp-1, and more specifically the product of its b transcript, is required for animals to suppress CO2 escape following acclimation to 21% O2.

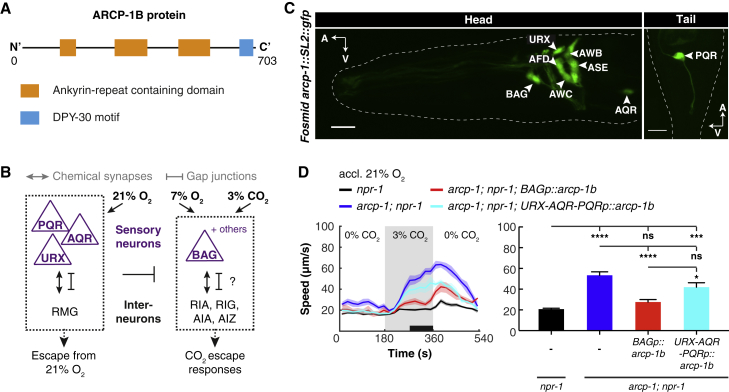

ARCP-1 Acts in BAG Sensory Neurons to Suppress CO2 Escape Behavior

arcp-1 encodes an ankyrin repeat protein (Figure 3A) homologous to C. elegans ankyrin UNC-44 and vertebrate ankyrins (Otsuka et al., 1995). These proteins are important for the subcellular localization of neural signaling complexes (e.g., anchoring components of the axon initial segment and allowing cyclic nucleotide-gated channels to accumulate in photoreceptor cilia) (Kizhatil et al., 2009, Leterrier et al., 2017, Maniar et al., 2011). Besides ankyrin repeats, ARCP-1 contains a DPY-30 domain (Figure 3A). Both domains are common protein interaction motifs that regulate the function and spatial organization of diverse signaling complexes (Gopal et al., 2012, Jones and Svitkina, 2016, Monteiro and Feng, 2017, Sivadas et al., 2012). ARCP-1’s domain structure suggests it serves a similar role trafficking or localizing signaling proteins in the nervous system.

Figure 3.

ARCP-1B Acts in BAG Sensors to Suppress CO2 Escape Behavior

(A) Protein domain architecture of ARCP-1B.

(B) Schematic model of the core neural circuits for O2 and CO2 responses in C. elegans (Fenk and de Bono, 2017, Guillermin et al., 2017, Laurent et al., 2015). O2-sensing neurons URX, AQR, and PQR tonically signal 21% O2. CO2 stimuli and O2 downshifts are detected by BAG and other neurons. The O2 sensors cross-modulate the neural circuit underlying CO2 escape. The role of RIA, RIG, AIA, and AIZ in the CO2 circuit is hypothesized based on their function in CO2 aerotaxis (Guillermin et al., 2017).

(C) A fosmid reporter transgene for arcp-1 is expressed in all major O2 and CO2 sensors, and other sensory neurons. Scale bar, 10 μm; A, anterior; V, ventral.

(D) Cell-specific expression of arcp-1b in BAG, using the flp-17 promoter (BAGp), rescues locomotory arousal by CO2, whereas expression in URX, AQR, and PQR, using the gcy-32 promoter (URX-AQR-PQRp), does not. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test. n ≥ 5 assays with 20–30 animals per trial. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

See also Figures S5 and S6.

A fosmid-based bicistronic transgene that co-expressed arcp-1 and free GFP was expressed in the main CO2 and O2 sensors: the URX, AQR, PQR, and BAG neurons (Figures 3B and 3C). We also observed expression in a subset of other sensory neurons (i.e., AFD, ASE, AWC, and AWB) (Figure 3C). This raised the possibility that disrupting arcp-1 modifies plasticity in multiple paradigms. To test this, we assayed arcp-1 mutants in a salt-based associative learning paradigm (Figure S6A; Beets et al., 2012, Hukema et al., 2008). arcp-1 mutants were defective in gustatory plasticity: although mock-conditioned animals showed normal attraction to NaCl, upon salt conditioning they failed to downregulate salt chemotaxis behavior (Figure S6B).

To gain insight into arcp-1 function, we focused on the failure of arcp-1 mutants to suppress CO2 escape when acclimated to 21% O2. Because arcp-1 is expressed in the BAG CO2 sensors, we asked if it acts in these neurons to suppress CO2 escape. Cell-specific expression of wild-type arcp-1 in BAG using the flp-17 promoter (Kim and Li, 2004) rescued the increased locomotory activity of arcp-1 mutants at 3% CO2 (Figure 3D). We also tested if arcp-1 can act in URX, AQR, and PQR neurons, which sense 21% O2, to suppress CO2 escape. Expressing arcp-1 in these neurons, using the gcy-32 promoter (Yu et al., 1997), did not rescue the CO2 phenotype of arcp-1 mutants (Figure 3D). By contrast, the arcp-1 aggregation defect could be rescued by expressing arcp-1 either in BAG or in URX, AQR, and PQR (Figures S5H and S5I). Together, these data show that arcp-1 functions in gas-sensing neurons and cell-autonomously suppresses CO2 escape in the BAG CO2 sensors.

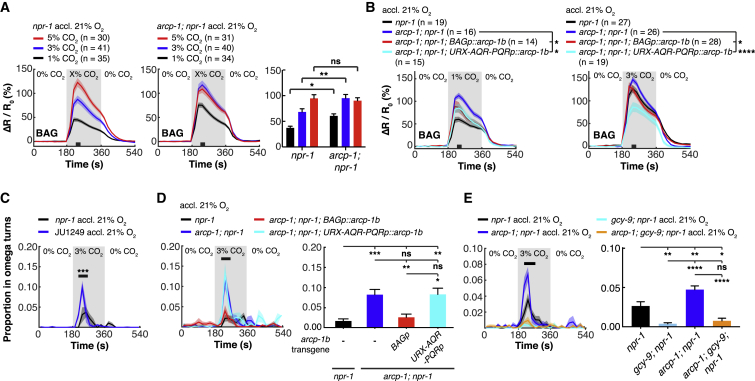

BAG Responses to CO2 Are Tuned by ARCP-1

We investigated if the increased behavioral response of arcp-1 animals to CO2 was associated with increased CO2-evoked Ca2+ responses in BAG neurons. Using the ratiometric sensor YC3.60, we quantified fluorescence changes at the cell body of BAG in response to CO2. Animals acclimated to 21% O2 were transferred to a microfluidic chamber kept at 7% O2 and stimulated with different CO2 concentrations. BAG Ca2+ responses evoked by 1% and 3% CO2 were significantly higher in arcp-1 mutants compared to controls (Figure 4A). Unlike for CO2 escape, expressing arcp-1 either in BAG or in URX, AQR, and PQR rescued the CO2 Ca2+ phenotype in BAG (Figure 4B). At 3% CO2, animals with arcp-1 rescued in URX, AQR, and PQR even showed a smaller increase in Ca2+ activity compared to npr-1 controls, which may be due to an overexpression effect of the gcy-32p::arcp-1b transgene (Figure 4B). Because BAG neurons exhibit a phasic-tonic response to CO2, we also measured Ca2+ responses during prolonged CO2 stimulation. BAG tonic responses to 3% CO2 were reduced in arcp-1 mutants, although the effect was small (Figure S6C).

Figure 4.

ARCP-1 Suppresses BAG Responses to CO2

(A and B) Mean traces of BAG Ca2+ activity in npr-1 and arcp-1; npr-1 animals in response to different CO2 concentrations. Mutants for arcp-1 show increased Ca2+ activity at 1% and 3% CO2 (A), which is rescued by expressing arcp-1 either in BAG (flp-17p) or URX, AQR, and PQR (gcy-32p) (B). n = number of animals. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test in (A). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šidák test in (B).

(C–E) CO2-evoked turning behavior. (C) Rising CO2 levels stimulate stronger turning behavior in JU1249 (n = 85 animals) than in npr-1(215F) animals (n = 81). Mann-Whitney U test. (D) CO2-evoked turning is also increased in arcp-1(db1082); npr-1(ad609) animals. BAG-specific expression of a flp-17p::arcp-1b transgene rescues this phenotype, whereas expression of arcp-1b in URX, AQR, and PQR (gcy-32p) does not. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test. n ≥ 5 assays with 20–30 animals per trial. (E) The increased turning of arcp-1; npr-1 animals in response to CO2 requires the GCY-9 CO2 receptor. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test. n = 9 assays with 20–30 animals per trial.

For (A)–(E), solid lines plot mean; shaded areas show SEM; black bars indicate time intervals for statistical comparisons; bar graphs plot mean ± SEM for these intervals. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

See also Figure S6.

BAG neurons respond not only to a rise in CO2, but also to a fall in O2 (Zimmer et al., 2009). We asked if the CO2 phenotypes of arcp-1 animals could be indirectly linked to changes in BAG’s ability to respond to O2. BAG Ca2+ activity at 7% O2, measured by YC2.60, was similar for arcp-1 mutants and npr-1 controls, although arcp-1 animals displayed higher Ca2+ at 21% O2 (Figure S6D). Ca2+ responses in URX to a 7% to 21% O2 stimulus were unaffected in arcp-1 animals (Figure S6E).

BAG O2 responses are mediated by the guanylate cyclases GCY-31/GCY-33 and are abolished in mutants of these genes (Zimmer et al., 2009). Animals lacking gcy-33 and gcy-31, like arcp-1 mutants, were aroused more strongly by CO2, but the effects on CO2 escape were additive in an arcp-1; gcy-33; gcy-31; npr-1 quadruple mutant (Figure S6F). Moreover, in gcy-33; gcy-31 mutants, CO2 arousal was suppressed when animals were acclimated to 21% O2—unlike in arcp-1 animals (Figure S6G). These results indicate that arcp-1 can act in a separate genetic pathway from gcy-33 and gcy-31 to regulate CO2 escape. Together with our rescue and Ca2+ imaging data, these findings are consistent with arcp-1 suppressing CO2 escape by inhibiting BAG responses to CO2.

ARCP-1 Inhibits BAG-Mediated Turning Downstream of the CO2 Receptor GCY-9

C. elegans respond to a rise in CO2 not only by becoming aroused and moving faster but also by re-orienting their direction of travel and increasing the frequency of sharp (omega) turns. This behavior is also mediated by BAG (Fenk and de Bono, 2015, Hallem and Sternberg, 2008). Because ARCP-1 acts in BAG to suppress CO2-evoked Ca2+ responses and locomotory arousal, we asked if it also inhibits CO2-evoked turning. Both arcp-1 mutants and JU1249 showed increased turning in response to a rise in CO2 compared to controls (Figures 4C and 4D). This phenotype was rescued by expressing arcp-1 in BAG, but not by expressing it in URX, AQR, and PQR (Figure 4D).

To gain insight into the molecular functions of arcp-1, we examined its effect on CO2-evoked turns further. This part of the locomotory response to CO2 is driven by cGMP signaling from the guanylyl cyclase receptor GCY-9 in BAG neurons (Fenk and de Bono, 2015, Hallem et al., 2011). GCY-9 is a molecular receptor for CO2 and appears to be specifically expressed in BAG (Hallem et al., 2011, Smith et al., 2013). To examine if arcp-1 regulates turning downstream of GCY-9, we measured CO2-evoked turns in a gcy-9; arcp-1 mutant. Disrupting gcy-9 abolished turning evoked by 3% CO2 in both npr-1 and arcp-1; npr-1 animals (Figure 4E), which implies that the mutant’s turning phenotype depends on GCY-9, and ARCP-1 antagonizes GCY-9 signaling in BAG.

ARCP-1 Localizes Phosphodiesterase PDE-1 to BAG Cilia

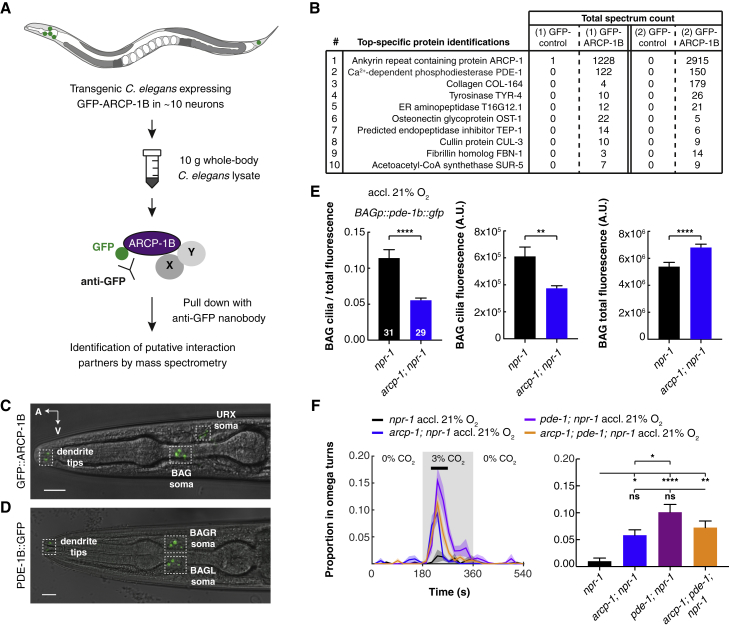

The ankyrin repeats and DPY-30 motif of ARCP-1 suggest it serves as an interaction partner or scaffold for other proteins. To identify its molecular partners, we took a biochemical approach (Figure 5A). We first made a transgenic strain that expressed GFP-ARCP-1B and showed that it rescued the enhanced CO2 response of the arcp-1 mutant (Figure S7A). We then used anti-GFP nanobodies to pull down GFP-ARCP-1B fusion proteins from C. elegans lysates and identified putative interacting proteins by mass spectrometry (Figure 5A; Data S3). As a negative control, we immunoprecipitated other GFP-tagged cytoplasmic proteins in parallel. Across two independent experiments, we identified phosphodiesterase 1 (PDE-1) as the top specific hit (i.e., the protein having the highest number of spectral counts in ARCP-1B immunoprecipitates [IPs] while having none in control IPs) (Figure 5B; Data S3).

Figure 5.

ARCP-1 Is a Scaffolding Protein that Localizes Phosphodiesterase PDE-1 to Dendritic Endings

(A) Schematic of coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) approach to identify ARCP-1B interactors, by pull-down of an N-terminal GFP tag.

(B) Top ten specific putative interactors of GFP-ARCP-1B identified in two independent coIPs. IPs of other cytoplasmic GFP-tagged proteins provide negative controls.

(C and D) GFP-tagged ARCP-1B and PDE-1B proteins are both enriched at the sensory endings of BAG. Scale bar, 10 μm; A, anterior; V, ventral.

(E) Disrupting arcp-1 reduces enrichment of PDE-1, expressed from the flp-17p, at BAG cilia. Bars plot mean ± SEM n (in bars) = number of animals. Mann-Whitney U test.

(F) pde-1 mutants phenocopy the increased turning frequency of arcp-1 mutants in response to CO2. pde-1; arcp-1 double mutants do not show an additive phenotype. Solid lines plot mean; shaded areas show SEM; black bars indicate time intervals for statistical comparisons; bar graphs plot mean ± SEM for these intervals. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test. n ≥ 8 assays with 20–30 animals per trial. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

PDE-1 is a Ca2+-activated cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/cyclic AMP (cAMP) phosphodiesterase orthologous to mammalian Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent PDE1 and is expressed in many neurons, including BAG (Couto et al., 2013, Hallem et al., 2011). As expected from our biochemical data, PDE-1 and ARCP-1 localize to similar compartments in BAG. GFP-tagged ARCP-1B was enriched at sensory endings (Figure 5C), similar to what we observe and what has been reported for PDE-1 (Martínez-Velázquez and Ringstad, 2018; Figure 5D).

The biochemical interaction of ARCP-1 and PDE-1, and their co-localization at dendritic endings, led us to hypothesize that ARCP-1 regulates PDE-1 localization. To test this, we compared enrichment of PDE-1 at BAG cilia in arcp-1 and control animals. Overall, PDE-1 expression was slightly higher in arcp-1 mutants, but enrichment of PDE-1 at the cilia was reduced by more than half in these animals (Figure 5E). To extend this observation, we investigated the subcellular localization of other signaling components of the gas-sensing neurons in arcp-1 mutants. We observed a reduction of GCY-9 levels in BAG cilia, as well as reduced levels of the O2-sensing guanylate cyclase GCY-35 at the sensory endings of URX (Figures S7B and S7C). These phenotypes were not due to a general defect in dendritic localization, because arcp-1 mutants showed normal levels of the cGMP-gated channel subunit TAX-4 and the O2-sensing guanylate cyclase GCY-33 in BAG cilia (Figures S7D and S7E). arcp-1 mutants did not exhibit overt defects in dendritic morphology, based on expression of a flp-17p::gfp transgene and DiI filling of amphid sensory neurons (Figures S7F and S7G). Together, our data suggest that ARCP-1 acts as a scaffold that helps co-localize signal transduction components at sensory endings of some neurons.

Our behavioral, Ca2+ imaging and cell biological results led us to speculate that ARCP-1 promotes a Ca2+-dependent feedback mechanism mediated by PDE-1, which keeps BAG CO2 responses in check by degrading cGMP following activation of the CO2 receptor GCY-9. If this is correct, disrupting pde-1 should phenocopy arcp-1 and increase the frequency of CO2-evoked turns. Moreover, the arcp-1 and pde-1 phenotypes should not be additive. As predicted, pde-1 mutants turned more in response to 3% CO2 than controls and even arcp-1 mutants, likely because pde-1 is more widely expressed and serves broader functions than arcp-1. The turning phenotype was comparable for pde-1, arcp-1, and pde-1; arcp-1 mutants (Figure 5F). These results are consistent with pde-1 and arcp-1 acting in the same genetic pathway to keep CO2 responses in check.

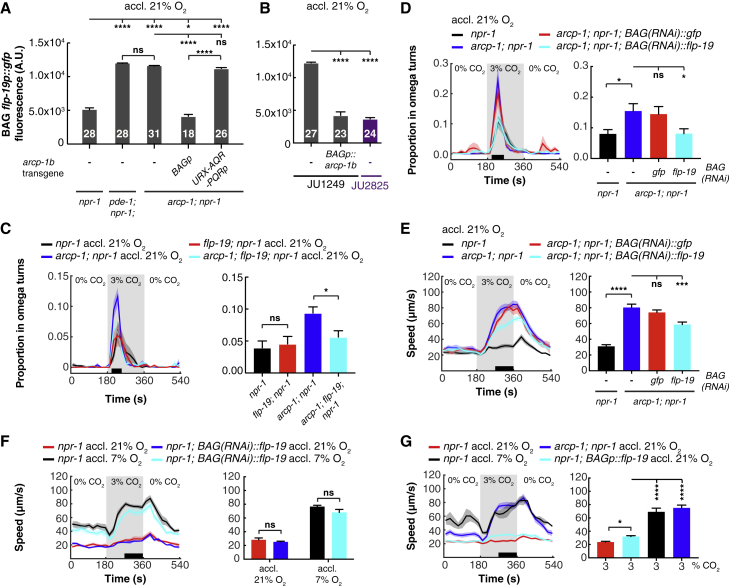

PDE-1 and ARCP-1 Inhibit Expression of FLP-19 Neuropeptides

To investigate further how disrupting arcp-1 alters BAG function, we specifically labeled these neurons with GFP, used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate the fluorescent cells from acutely dissociated arcp-1;npr-1 and npr-1 control animals, and profiled their gene expression using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (see STAR Methods). Genes that are hallmarks of BAG, such as those involved in CO2 signaling (gcy-9, pde-1, flp-17) and BAG cell fate determination (ets-5) (Guillermin et al., 2011, Hallem et al., 2011), were among the top enriched genes in our dataset (Data S4). arcp-1 itself was among the 100 most highly expressed genes in BAG. The BAG profiles highlighted significant gene expression differences between arcp-1 mutants and controls, notably changes in the abundance of mRNAs encoding neuropeptides, genes involved in ciliary intraflagellar transport, ion channels, and gap junction subunits (see Discussion; Data S4D). These data suggest that loss of ARCP-1 leads to altered gene expression.

One of the most abundant transcripts expressed in BAG whose expression was significantly altered by defects in arcp-1 was the neuropeptide flp-19. flp-19 expression was upregulated 2.4-fold in arcp-1 animals, which would be consistent with increased BAG signaling. Previous work has shown that GCY-9, PDE-1, and the cGMP-gated Ca2+ channel TAX-4 control flp-19 expression in BAG (Romanos et al., 2017), making it an interesting candidate for altering CO2 responses in the arcp-1 mutant. To confirm that defects in arcp-1 increased expression of flp-19, we introduced a flp-19p::gfp reporter transgene (Kim and Li, 2004) into arcp-1 mutants and quantified fluorescence in BAG neurons. Disrupting arcp-1 significantly increased BAG expression of the neuropeptide reporter (Figure 6A). This phenotype was rescued by expressing wild-type arcp-1 in BAG, but not in the O2 sensors URX, AQR, and PQR (Figure 6A). Thus, arcp-1 controls flp-19 expression cell-autonomously in BAG. We observed a similar increase in expression of the flp-19 reporter when pde-1 was mutated (Figure 6A). BAG expression of flp-19 in mutants lacking both arcp-1 and pde-1 was similar to that of the single mutants (Figure S7H). These data suggest that ARCP-1 and PDE-1 together reduce BAG signaling by lowering the expression of some neuropeptides. However, disrupting arcp-1 does not generally increase BAG neuropeptide expression as judged from our BAG profiling experiments (Data S4) and analysis of a flp-17 neuropeptide reporter in BAG (Figure S7I).

Figure 6.

PDE-1 and ARCP-1 Inhibit BAG Expression of FLP-19 Neuropeptides that Potentiate Behavioral Responses to CO2

(A) Mean fluorescence ± SEM of a flp-19 neuropeptide reporter (flp-19p::gfp) in BAG, indicating that PDE-1 and ARCP-1 inhibit flp-19 expression. BAG-specific expression of arcp-1b, using the flp-17 promoter (BAGp), rescues this phenotype, whereas expression in URX, AQR and PQR, using the gcy-32 promoter (URX-AQR-PQRp), does not. n (in bars) = number of animals. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test.

(B) Mean fluorescence ± SEM of flp-19 neuropeptide reporter in BAG neurons of JU1249 and JU2825. Increased expression of flp-19 in JU1249 is rescued by expressing arcp-1b from the BAG-specific flp-17 promoter (BAGp). n (in bars) = number of animals. Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn test.

(C) Disrupting flp-19 suppresses the potentiated turning phenotype of arcp-1; npr-1 animals in response to 3% CO2. One-way ANOVA with Holm Šidák test. n = 9 assays.

(D) CO2-evoked turning of arcp-1; npr-1 mutants following cell-specific knock down of flp-19 expression in BAG. Knock down of flp-19 in the mutant background suppresses turning at 3% CO2, whereas knock down of gfp does not. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. n ≥ 7 assays.

(E) Knock down of flp-19 expression in BAG partially rescues the increased arousal phenotype of arcp-1; npr-1 animals at 3% CO2. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. n ≥ 7 assays with 20–30 animals per trial.

(F) BAG-specific knock down of flp-19 in npr-1 animals does not affect the plasticity of CO2 escape in response to previous O2 experience. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák test. n = 7–8 assays.

(G) Animals overexpressing flp-19 in BAG move significantly faster at 3% CO2 compared to npr-1 controls, although their response is still lower than npr-1 animals grown at 7% O2 and arcp-1 mutants. n ≥ 3 assays. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test.

For (C)–(G), 20–30 animals were tested per assay. Solid lines plot mean; shaded areas show SEM; black bars indicate time intervals for statistical comparisons; bars plot mean ± SEM for these intervals. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

To ask if flp-19 expression was elevated in JU1249, we backcrossed the flp-19p::gfp transgene ten times to this isolate. We did the same for JU2825 that, unlike JU1249, suppressed CO2 escape when acclimated to 21% O2 (Figure S2A). BAG expression of flp-19 was low in JU2825 and high in JU1249 (Figure 6B). Restoring arcp-1 in BAG significantly reduced flp-19 expression (Figure 6B). Thus, disrupting arcp-1 also increases flp-19 expression in JU1249.

FLP-19 Neuropeptide Signaling from BAG Potentiates Behavioral Responses to CO2

Does increased BAG expression of flp-19 in arcp-1 mutants enhance the behavioral responses of these animals to CO2? If increased flp-19 expression heightened aversion to CO2 in arcp-1 animals, then disrupting flp-19 should reverse this phenotype. Consistent with this hypothesis, deleting flp-19 restored turning at 3% CO2 in the arcp-1 mutant, while it had no effect on this behavior in npr-1 animals (Figure 6C).

To confirm that FLP-19 release from BAG potentiates CO2 responses, we knocked down flp-19 expression specifically in these neurons by expressing RNAi sense and antisense sequences of flp-19 from a BAG-specific gcy-33 promoter (Hallem et al., 2011, Yu et al., 1997). As a negative control, we expressed sense and antisense sequences for gfp under the same promoter and found it had no effect on CO2 responses (Figures 6D and 6E). By contrast, BAG-specific knockdown of flp-19 in arcp-1 mutants restored the frequency of CO2-evoked turns (Figure 6D) and reduced CO2-evoked locomotory arousal in animals acclimated to 21% O2 (Figure 6E). These data suggest increased flp-19 expression in BAG contributes to the enhanced behavioral responses to CO2 in arcp-1 mutants.

The neuropeptide gene flp-19 is also expressed in URX. However, knock down of flp-19 in these neurons, using the gcy-32 promoter, enhanced rather than reduced locomotory arousal at 3% CO2 in arcp-1 animals and increased baseline locomotion in the absence of CO2 (Figure S7K). This result is consistent with previous reports (Carrillo et al., 2013) and suggests that the RNAi effect in BAG is specific to these neurons. We wondered if altered expression of flp-19 from URX contributes to the enhanced CO2 aversion in arcp-1 animals as well. If this is the case, flp-19 expression in URX should be reduced in arcp-1 mutants. Indeed, disrupting arcp-1 decreased expression of the flp-19 reporter in URX. This phenotype was rescued by expressing arcp-1 either in URX or BAG neurons (Figure S7L), suggesting that BAG signaling indirectly influences flp-19 expression in URX.

Does FLP-19 release from BAG promote escape from CO2 in animals that retain functional arcp-1? In npr-1 animals, BAG-specific knock down of flp-19 did not compromise CO2 escape in animals acclimated to 21% O2 or 7% O2 (Figure 6F). Thus, flp-19 is not required for the O2-dependent modulation of CO2 responses. Consistent with this finding, we observed similar expression of the flp-19 reporter in npr-1 animals acclimated to 21% or 7% O2, suggesting that flp-19 expression is not regulated by O2 experience (Figure S7J).

We next asked if increased flp-19 expression in BAG is sufficient to boost C. elegans’ locomotory arousal by CO2. To test this, we overexpressed flp-19 specifically in the BAG neurons of npr-1 animals, acclimated these transgenic animals to 21% O2, and quantified their speed at 3% CO2. Animals overexpressing flp-19 in BAG moved significantly faster at 3% CO2 than npr-1 controls, although their locomotory arousal was weaker than that of arcp-1 animals or of npr-1 animals grown at 7% O2 (Figure 6G). Thus, acclimation to 7% O2 or disrupting arcp-1 alters other signals besides flp-19 to heighten CO2 responses. However, in both scenarios—disruption of arcp-1 or O2 acclimation—increasing flp-19 expression in BAG can potentiate behavioral responses to CO2, leading to increased CO2 aversion.

Discussion

Individuals differ in how they respond to altered circumstances in their environment. This is generally ascribed to a combination of genetic variation and different life experiences. How neural circuits encoding behavioral plasticity vary across individuals is, however, poorly understood. Here, we show that Caenorhabditis species and wild isolates of C. elegans can differ in how past O2 experience influences CO2 escape behavior. We uncover a genetic variant and neuronal mechanism responsible for this variation in behavioral flexibility in one natural C. elegans isolate.

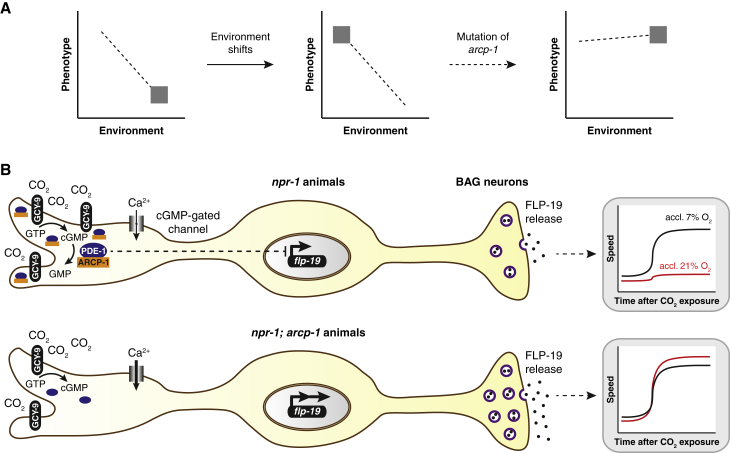

The behavioral phenotypes that we observe are reminiscent of genetic accommodation, when the reaction norm of a flexible phenotype responsive to the environment is altered by genetic change (Figure 7A). Underlying this behavioral change, we find that disrupting ARCP-1 both increases CO2 sensitivity and alters the effect of previous O2 experience on CO2 escape. Animals lacking this dendritic scaffold protein become strongly aroused by CO2 regardless of previous O2 experience, and acclimation to 21% O2 further enhances, rather than suppresses, escape from this aversive cue. We show that loss of arcp-1 mediates these phenotypes by directly altering CO2 responses, rather than by affecting the ability to respond to O2.

Figure 7.

A Model for How Genetic Variation in arcp-1 Affects CO2 Escape Behavior

(A) Effect of the natural arcp-1 allele on experience-dependent plasticity, shown as behavioral reaction norms. C. elegans wild isolates acclimated to a high (21%) O2 environment suppress their aversion to CO2 (left panel). A shift to a low (7%) O2 environment results in a heightened CO2 response. A mutation in arcp-1 alters experience-dependent plasticity and genetically fixes a strong aversive response to CO2 in part by increasing flp-19 neuropeptide expression in BAG CO2 sensors (right panel).

(B) CO2 is detected by the receptor guanylate cyclase GCY-9, expressed in BAG cilia. The ankyrin-repeat scaffold protein ARCP-1 is also enriched at dendritic sensory endings, interacts with PDE-1, and localizes this phosphodiesterase to the cilia of BAG CO2-sensory neurons. PDE-1 and ARCP-1 inhibit CO2-evoked Ca2+ activity and expression of FLP-19 neuropeptide messengers in BAG. In the absence of ARCP-1, less GCY-9 and PDE-1 localize to BAG cilia, and flp-19 is more strongly expressed. Increased FLP-19 expression in BAG contributes to resetting a strong aversive response to CO2 in arcp-1; npr-1 animals regardless of previous O2 experience.

We identify the BAG CO2 sensors as the main site where ARCP-1 suppresses CO2 escape in animals acclimated to 21% O2. Together with previous work (Couto et al., 2013, Romanos et al., 2017), our results suggest a model (Figure 7B) in which ARCP-1 binds and co-localizes the Ca2+-activated phosphodiesterase PDE-1 with guanylyl cyclase receptors for CO2 at the BAG cilia. ARCP-1 and PDE-1 keep signaling from these neurons in check by suppressing CO2-evoked Ca2+ responses and neuropeptide expression. Natural genetic variation has been found to directly alter sensory systems in other animals (McGrath, 2013, Prieto-Godino et al., 2017). We identify BAG as a major cellular focus for variation in CO2 responses, but the possibility remains that loss of arcp-1 disrupts plasticity in other sensory circuits, which may indirectly promote CO2 aversion as well. Some evidence points to changes in URX, but these are not sufficient to explain the heightened CO2 escape behavior in arcp-1 mutants.

Mounting evidence suggests that natural variation in behavioral flexibility is genetically determined (Izquierdo et al., 2007, Mery, 2013, Mery et al., 2007). One well-established example is the natural variation seen at the foraging gene in Drosophila melanogaster. This polymorphism causes individual variation in learning and memory, among other phenotypes, by altering the activity of cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (Mery et al., 2007). It is notable that, both in flies and worms, genetic variation affecting cGMP signaling underlies inter-individual variation in experience-dependent plasticity. Besides gas sensors, ARCP-1 is expressed in olfactory, gustatory, and thermosensory neurons that all signal using cGMP, and arcp-1 mutants show reduced plasticity in a gustatory paradigm. Correlated differences in the plasticity of different sensory modalities have been described as coping styles or behavioral syndromes in other animal models (Coppens et al., 2010) and may also reflect a common genetic or molecular basis. Identifying how loss of arcp-1 compromises plasticity in other sensory circuits should provide a better understanding of such correlated changes in behavioral flexibility.

We have shown that the absence of ARCP-1 alters expression of a range of genes in BAG. One way this influences CO2 aversion is by altering the expression of neuropeptide messengers. Neuropeptides are a diverse group of neuromodulators that, both in vertebrates and invertebrates, are involved in circuit plasticity (Jékely et al., 2018, Taghert and Nitabach, 2012). Natural genetic variation in neuropeptide pathways has been linked to individual differences in aging and social behaviors (Donaldson and Young, 2008, Yin et al., 2017). Our results suggest that they also contribute to heritable differences in behavioral plasticity between individuals. In humans and other primates, natural polymorphisms in serotonergic and dopaminergic systems have been associated with individual differences in memory and cognitive ability (Izquierdo et al., 2007, Zhang et al., 2007). Changing the neuromodulatory tone of circuits likely represents a general mechanism by which genetic variation sculpts individual behavioral plasticity.

Disrupting ARCP-1 increases expression of FLP-19 neuropeptides in BAG. This potentiates or disinhibits both CO2-evoked turning and locomotory arousal in animals acclimated to 21% O2. A FLP-19 receptor is currently unknown; the C. elegans genome encodes ∼150 predicted neuropeptide receptors but none have been reported to bind FLP-19 (Peymen et al., 2014). FLP-19 neuropeptides belong to the ancient and conserved family of RFamide neuropeptides (Peymen et al., 2014). Previous work suggested that CO2-evoked cGMP and Ca2+ signaling promote flp-19 expression in BAG, and this effect is counterbalanced by PDE-1 (Romanos et al., 2017). In arcp-1 mutants, the GCY-9 CO2 receptor and PDE-1 are less enriched at BAG cilia. Although gcy-9 expression is slightly reduced, disrupting ARCP-1 increases BAG Ca2+ activity in response to CO2. This is consistent with proper ciliary localization of PDE-1 keeping BAG Ca2+ signaling in check and could explain the increased flp-19 expression. ARCP-1 and PDE-1 may also orchestrate microdomains of cGMP that can regulate gene expression (Arora et al., 2013, O’Halloran et al., 2012). In vertebrate neurons, nanodomains of the ankyrin G protein, a homolog of ARCP-1, localize to the dendritic spines and the axon initial segment and contribute to neural plasticity (Grubb and Burrone, 2010, Smith et al., 2014). Likewise, mammalian PDE1 has been implicated in the experience-dependent adaptation of sensory responses. In mouse olfactory neurons, PDE1 is specifically enriched at the cilia, although a molecular anchor that localizes the protein to this compartment has not yet been identified (Cygnar and Zhao, 2009).

The molecular mechanism by which ARCP-1 controls flp-19 expression, and whether this relates to its ciliary function, remains to be understood. Interestingly, our transcriptional profiling of BAG neurons revealed a suite of genes involved in intraflagellar transport, including the axonemal dynein che-3, that show ∼2-fold increased expression in arcp-1 animals, although we did not observe obvious defects in cilia morphology. This suggests a feedback mechanism exists by which signaling at the cilium regulates expression of genes involved in ciliary transport. Identifying the molecular factors involved is the next step forward toward understanding this transcriptional regulation.

The mechanisms through which natural genetic variation in arcp-1, acting on an evolutionary timescale, and O2 experience, acting over an animal’s lifetime, sculpt CO2 responsiveness seem to be at least partly distinct. However, in both scenarios—disruption of arcp-1 or acclimation to different O2 environments—release of FLP-19 neuropeptides from BAG can boost the animal’s response to this aversive cue, and through alterations in neuropeptide expression, a strong aversive response may become fixed.

CO2 responses vary between Caenorhabditis species (Carrillo and Hallem, 2015, Pline and Dusenbery, 1987, Viglierchio, 1990). Our results show this variation is at least in part due to differences in O2-dependent modulation, suggesting it is an adaptive trait. We speculate that the influence of O2 memory on other sensory responses enables animals to reconfigure their behavioral priorities according to past experience (Fenk and de Bono, 2017). Animals at the surface may prioritize escape from 21% O2 and gradually suppress their CO2 aversion to facilitate migration to buried environments with less aeration and elevated CO2 levels. Natural variation in the O2-dependent modulation of CO2 escape may result in animals occupying different ecological niches. Alternatively, there could be selection against the costs to maintain sensory systems for behavioral plasticity (Dewitt et al., 1998), which may account for the reduced plasticity of CO2 responses in some nematode species. We do not know the O2 and CO2 conditions in which the arcp-1 deletion may have been selected and can therefore only speculate about its potential fitness benefits. The arcp-1 mutation was not found in any other wild isolate so is likely recent. However, our data indicate substantial variation among both Caenorhabditis species and C. elegans isolates in the response to CO2 (Figures 1 and S2). These findings are consistent with what has been found for other traits (Frézal et al., 2018), where the phenotypic variation for the strain chosen for study is caused by a rare allele found only in that strain, yet phenotypic variation itself is not restricted to that strain. Understanding evolutionary mechanisms that might select for altered plasticity requires more in-depth knowledge on the ecology of these species. The behavioral phenotypes that we observe are consistent with genetic accommodation for a cross-modal gene-environment interaction (Pigliucci et al., 2006). In summary, our study illustrates how natural genetic variation, by altering the neuromodulatory control of aversive behavior, contributes to individual differences in behavioral flexibility.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| GFP-Trap Agarose | ChromoTek | Cat#gta-20; RRID: AB_2631357 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli: Strain OP50 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Wormbase: OP50; RRID: WB-STRAIN:OP50 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Dermabond tissue adhesive for worm glueing | Ethicon | Cat#AHV12 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| SuperScript II reverse transcriptase | Invitrogen | Cat#18064-014 |

| KAPA Hifi HotStart kit | KAPA Biosystems | Cat#KK2601 |

| Ampure XP beads | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A63881 |

| Nextera XT DNA sample preparation kit | Illumina | Cat#FC-131-1096 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Genome sequence data of JU1249 and JU2825 | This paper | NCBI: PRJNA514933 |

| Genome sequence data of replicate populations for QTL mapping | This paper | NCBI: PRJNA515248 |

| RNA-Seq data of sorted BAG neurons | This paper | GEO: GSE135687 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans: Strain AX1796: glb-5(Haw) V; npr-1(g320) X | de Bono lab; Persson et al., 2009 | AX1796 |

| C. elegans: Strain LSJ1: Bristol strain | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:LSJ1 |

| C. angaria: Strain RGD1: Caenorhabditis angaria wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:RGD1 |

| C. latens: Strain VX80: Caenorhabditis latens wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:VX80 |

| C. japonica: Strain DF5081: Caenorhabditis japonica wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:DF5081 |

| C. wallacei: Strain JU1904: Caenorhabditis wallacei wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1904 |

| C. tropicalis: Strain JU1373: Caenorhabditis tropicalis wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1373 |

| C. briggsae: Strain HK105: Caenorhabditis briggsae wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:HK105 |

| C. nigoni: Strain JU1422: Caenorhabditis nigoni wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1422 |

| C. sinica: Strain JU800: Caenorhabditis sinica wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU800 |

| C. elegans: Strain ED3011: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:ED3011 |

| C. elegans: Strain ED3073: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:ED3073 |

| C. elegans: Strain EG4946: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:EG4946 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU258: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU258 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU561: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU561 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU1088: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1088 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU1248: C. elegans wild isolate | M.-A. Félix; Troemel et al., 2008 | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1248 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU1543: C. elegans wild isolate | M.-A. Félix | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1543 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU2825: C. elegans wild isolate | M.-A. Félix | JU2825 |

| C. elegans: Strain MY16: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:MY16 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU1249: C. elegans wild isolate | M.-A. Félix; Zhang et al., 2016 | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1249 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX613: npr-1(g320) X | de Bono lab; Persson et al., 2009 | AX613 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU3221: arcp-1(mfP22) III; npr-1(215F) X; mfEx94 [arcp-1p::arcp-1b::sl2::gfp; myo-2p::dsRed2] in JU1249 background | This paper | JU3221 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX204: npr-1(ad609) X | de Bono lab; Persson et al., 2009 | AX204 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6574: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X 4x outcrossed | This paper | AX6574 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7324: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X 5x outcrossed | This paper | AX7324 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6723: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx975 [arcp-1p::arcp-1b::sl2::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6723 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7094: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1050 [arcp-1p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; lin-44p::gfp] | This paper | AX7094 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6720: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx974 [arcp-1p::arcp-1a::sl2::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6720 |

| C. elegans: Strain N2: C. elegans Bristol strain | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:N2_(ancestral) |

| C. elegans: Strain MY10: C. elegans wild isolate | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID: WB-STRAIN:MY10 |

| C. elegans: Strain JU1247: C. elegans wild isolate | M.-A. Félix, (Troemel et al., 2008) | RRID: WB-STRAIN:JU1247 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6901: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1002 [fosmid arcp-1p::arcp-1::sl2::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6901 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6766: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx984 [gcy-32p::arcp-1b::sl2::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6766 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6805: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx990 [flp-17p::arcp-1b::sl2::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6805 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6931: arcp-1(gk856856) III; npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX6931 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6929: arcp-1(gk863317) III; npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX6929 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6927: arcp-1(gk852871) III; npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX6927 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7023: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1035 [gcy-32p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; lin-44p::gfp] | This paper | AX7023 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7095: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx990 [flp-17p::arcp-1b::sl2::gfp; unc-122p::rfp]; dbEx1035 [gcy-32p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; lin-44p::gfp] | This paper | AX7095 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7179: gcy-9(n4470) npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7179 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7238: arcp-1(db1082) III; gcy-9(n4470) npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7238 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7116: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbIs20 [arcp-1p::gfp::arcp-1b; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7116 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6969: malt-1(db1194) II; npr-1(ad609) X; dbIs16 [rab-3p::malt-1::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6969 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7082: eif-3.L(db1015) II; npr-1(ad609) X; dbIs19 [rab-3p::eif-3.L::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7082 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7419: npr-1(ad609) X dbEx1075 [flp-17p::pde-1b::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7419 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7422: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1075 [flp-17p::pde-1b::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7422 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX2272: pde-1(ok2924) I; npr-1(ad609) X | de Bono lab; Couto et al., 2013 | AX2272 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7453: pde-1(ok2924) I; arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7453 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6881: npr-1(ad609) X dbEx [flp-17p::YC3.60] | This paper | AX6881 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6893: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx [flp-17p::YC3.60] | This paper | AX6893 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7842: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx [flp-17p::YC3.60]; dbEx1035 [gcy-32p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; lin-44::gfp] | This paper | AX7842 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7845: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx [flp-17p::YC3.60] dbEx1172 [gcy-33p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; unc-122p::gfp] | This paper | AX7845 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX3516: npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx614 [gcy-37p::YC2.60; unc-122p::rfp] | de Bono lab; Fenk and de Bono, 2017 | AX3516 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6877: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx614 [gcy-37p::YC2.60; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX6877 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX3432: npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx623 [flp-17p::YC2.60; F15E11.1::mCherry] | de Bono lab; Gross et al., 2014 | AX3432 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7182: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx623 [flp-17p::YC2.60; F15E11.1::mCherry] | This paper | AX7182 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7656: gcy-33(ok232) V; gcy-31(ok296) npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7656 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7657: arcp-1(db1082) III; gcy-33(ok232) V; gcy-31(ok296) npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7657 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7362: npr-1(ad609) X; wzIs132 [gcy-9p::gcy-9::dsRed] | This paper | AX7362 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7361: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; wzIs132 [gcy-9p::gcy-9::dsRed] | This paper | AX7361 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7366: npr-1(ad609) X; wzEx156 [gcy-9p::tax-4::gfp] | This paper | AX7366 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7365: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; wzEx156 [gcy-9p::tax-4::gfp] | This paper | AX7365 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX2997: gcy-33(ok232) V; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx [flp-17p::gcy-33::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | de Bono lab; Gross et al., 2014 | AX2997 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7315: arcp-1(db1082) III; gcy-33(ok232) V; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx [flp-17p::gcy-33::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7315 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX6516: npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1053 [gcy-37p::gcy-35::HA::gfp::sl2::mCherry] | This paper | AX6516 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7278: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1053 [gcy-37p::gcy-35::HA::gfp::sl2::mCherry] | This paper | AX7278 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7019: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1033 [flp-17p::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7019 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7021: npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1033 [flp-17p::gfp; unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7021 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7268: npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] | This paper | AX7268 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7271: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] | This paper | AX7271 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7279: pde-1(ok2924) I; npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] | This paper | AX7279 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7272: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp]; dbEx1063 [flp-17p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; unc-122p::gfp] | This paper | AX7272 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7273: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] dbEx1035 [gcy-32p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; lin-44::gfp] | This paper | AX7273 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7550: pde-1(ok2924) I; arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] | This paper | AX7550 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7722: ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] backcrossed 10x in JU2825 background | This paper | AX7722 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7724: ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] backcrossed 10x in JU1249 background | This paper | AX7724 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7726: dbEx1063 [flp-17p::arcp-1b::sl2::mKate; unc-122p::gfp]; ynIs34 [flp-19p::gfp] backcrossed 10x in JU1249 background | This paper | AX7726 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7210: npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs64 [flp-17p::gfp] | This paper | AX7210 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7208: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; ynIs64 [flp-17p::gfp] | This paper | AX7208 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7321: flp-19(ok2460) npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7321 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7322: arcp-1(db1082) III; flp-19(ok2460) npr-1(ad609) X | This paper | AX7322 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7754: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1171 [gcy-33p::gfp (sas); unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7754 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7760: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1173 [gcy-33p::flp-19 (sas); unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7760 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7788: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1178 [gcy-32p::gfp (sas); unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7788 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7678: arcp-1(db1082) III; npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1153 [gcy-32p::flp-19 (sas); unc-122p::gfp] | This paper | AX7678 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7793: npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1173 [gcy-33p::flp-19 (sas); unc-122p::rfp] | This paper | AX7793 |

| C. elegans: Strain AX7437: npr-1(ad609) X; dbEx1077 [flp-17p::flp-19::sl2::mKate; unc-122p::gfp] | This paper | AX7437 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers used in this study | This paper | Table S2 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FlyCapture | Point Grey Research | https://www.flir.com/products/flycapture-sdk |

| Zentracker | Laurent et al., 2015 | https://github.com/wormtracker/zentracker |

| Neuron Analyzer | Laurent et al., 2015 | https://github.com/neuronanalyser/neuronanalyser |

| RStudio 0.99.903 | R Development Core Team, 2015 | https://www.R-project.org |

| Pindel | Ye et al., 2009 | http://gmt.genome.wustl.edu/packages/pindel/ |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | McLaren et al., 2016 | www.ensembl.org/info/docs/tools/vep/index.html |

| Tablet 1.16.09.06 | Milne et al., 2013 | https://ics.hutton.ac.uk/tablet/ |

| BWA 0.7.8-R455 | Li and Durbin, 2009 | http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml |

| Samtools 1.2 | Li et al., 2009 | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ |

| Picard 1.114 | Broad Institute | http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ |

| GATK 3.2-2 | Van der Auwera et al., 2013 | https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/ |

| Bowtie2 0.11.0 | Langmead and Salzberg, 2012 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| rRNA remover code | This paper | https://github.com/lmb-seq/RNA-Seq_utilities |

| Code for concatenating FASTQ files | This paper | https://github.com/lmb-seq/RNA-Seq_utilities |

| PRAGUI RNA-Seq analysis pipeline | This paper | https://github.com/lmb-seq/PRAGUI |

| Mascot | Matrix Science | http://www.matrixscience.com/ |

| Scaffold | Proteome Software Inc | http://www.proteomesoftware.com/products/scaffold/ |

| Prism 7.0 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| MATLAB R2014b 8.4 | Mathworks | https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html |

| Metamorph | Molecular Devices | https://www.moleculardevices.com/products/cellular-imaging-systems/acquisition-and-analysis-software/metamorph-microscopy#gref |

| Fiji (ImageJ) | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://imagej.net/Fiji |

| Imaris | Bitplane | https://imaris.oxinst.com/ |

| Other | ||

| Certified gas mixes | BOC | N/A |

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Mario de Bono (debono@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk, mdebono@ist.ac.at).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Animals

C. elegans and other Caenorhabditis species were maintained under standard conditions (Stiernagle, 2006) on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates seeded with E. coli OP50. Young adult hermaphrodites were used in all experiments. For gonochoristic Caenorhabditis species, young adult females were used. For a list of strains and transgene details, see Table S1 and the Key Resources Table.

The mutations in arcp-1 alleles obtained by forward genetics, and in the JU1249 wild isolate, are shown in Figure S5A. The C. elegans strain JU1249 was isolated from a rotten apple collected in 2007 in Santeuil, France (Zhang et al., 2016). A detailed description of the forward genetic screen that isolated the db1082 allele will be described elsewhere. Causal variants in aggregation-defective mutants from this screen were identified by SNP-based mapping in combination with WGS (Minevich et al., 2012).

Microbe strains

The Escherichia coli OP50 strain was used as a food source for C. elegans and other Caenorhabditis species.

Method Details

Molecular biology

Transgenes were cloned using the Multisite Gateway Three-Fragment cloning system (12537-023, Invitrogen) into pDESTR4R3 II. For transgenic lines, the promoter lengths were: arcp-1p (1.2 kb for arcp-1a and 2 kb for arcp-1b), flp-17p (3.3 kb), gcy-32p (0.6 kb), and gcy-33p (1.0 kb). For rescue experiments, cDNA of arcp-1 isoforms was amplified and cloned into pDONR221, using primers listed in Table S2.

For immunoprecipitation and subcellular localization of ARCP-1, a functional arcp-1p::gfp::arcp-1b transgene was made by fusing GFP coding sequences upstream of the arcp-1b cDNA sequence. To investigate the subcellular localization of PDE-1 in BAG neurons, the pde-1b cDNA sequence was cloned into pDONR221 using primers listed in Table S2. This plasmid was used to generate a flp-17p::pde-1b::gfp transgene, by cloning the GFP reporter sequence in frame and downstream of the pde-1b cDNA sequence. Details of strains and transgenes used to study the subcellular localization of gcy-9, tax-4, gcy-33 and gcy-35 are provided in Table S1. The gcy-9p::gcy-9::mCherry and gcy-9p::tax-4::gfp strains were a kind gift from Dr. Niels Ringstad (New York University School of Medicine, USA).

For flp-19 RNAi, 469 bp of flp-19 cDNA starting from the sequence GCTTTTCCTGTTAA was cloned in both the sense and antisense orientations. For cell-specific RNAi experiments, we expressed these fragments in BAG using the gcy-33p (1.0 kb) and in URX neurons using gcy-32p (0.6 kb). To overexpress flp-19 in BAG, we amplified flp-19 cDNA using primers listed in Table S2, and fused this sequence to the flp-17 (3.3 kb) promoter.

To characterize the expression pattern of arcp-1, we made a fluorescent reporter transgene by fosmid recombineering. pBALU9 was used to amplify a reporter cassette, containing the gpd-2 intergenic SL2 sequence and a GFP coding sequence, which was inserted downstream of the arcp-1 stop codon in the WRM0633bA06 fosmid as described (Tursun et al., 2009). The reporter strain for flp-19 neuropeptide expression (flp-19p::gfp) was a kind gift from Dr. Roger Pocock (Monash University, Australia).

Genotyping of natural polymorphisms

Polymorphisms of npr-1, glb-5, nath-10 and arcp-1 genes in C. elegans wild isolates were genotyped by PCR. Primers used are listed in Table S2.

Behavioral assays

All experiments used young adult hermaphrodite animals, therefore sample stratification was not required within each genotype/condition. For most experiments, measurements were scored using an automated algorithm so blind scoring was not undertaken: see each subsection for details. For details of statistical tests, see the relevant Figure legend for each experiment and also the subsection ‘‘Quantification and Statistical Analysis.’’ All recordings that passed the automated analysis pipeline were included in the final dataset. For rescue and RNAi experiments, behavioral responses and phenotypes were confirmed by testing at least two independent transgenic strains.

Locomotory responses to CO2 and O2

Behavioral responses to gas stimuli were assayed as described (Fenk and de Bono, 2017, Laurent et al., 2015). Animals were acclimated to different O2 levels by growing them for one generation at 21% O2 (room air) or in a gas-controlled incubator kept at 7% O2. For each assay, 20-30 young adult hermaphrodites were transferred onto NGM plates seeded 16–20 h earlier with 20 μL of E. coli OP50. To control gas levels experienced by C. elegans, animals were placed under a 200 μm deep square polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chamber with inlets connected to a PHD 2000 Infusion syringe pump (Harvard apparatus). Humidified gas mixtures were delivered at a flow rate of 3.0 ml/min. Behavioral responses to changes in O2 levels were measured by exposing animals to a stimulus train of 7% O2 - 21% O2 - 7% O2 (upshift) or 21% O2 - 7% O2 - 21% O2 (downshift), in which each stimulus comprised a 3 min time interval. Locomotory responses to CO2 were measured by exposing animals to a series of 0% CO2 (3 min) - X% CO2 (3 min) - 0% CO2 (3 min), with X corresponding to 1%, 3%, 5% or 10% CO2 depending on the experiment. In all CO2 assays, a background level of 7% O2 was used. Movies were recorded during the stimulus train using FlyCapture (Point Grey Research) on a Leica MZ6 dissecting microscope with a Point Grey Grasshopper camera running at 2 frames/s. Video recording was started 2 min after animals were placed under the PDMS chamber to ensure that the initial environment was in a steady state. In assays where we prolonged the exposure to 7% O2 before CO2 stimulation, video recording was started 21 min after animals were placed under the PDMS chamber kept at 7% O2, and animals were stimulated with 3% CO2 at t = 24 min. Videos were analyzed in Zentracker, a custom-written MATLAB software (https://github.com/wormtracker/zentracker). All worms in the field of view were analyzed except those in contact with other animals. Speed was calculated as instantaneous centroid displacement between successive frames. Omega turns were identified as described (Laurent et al., 2015). In total 2-4 assay plates with 20-30 animals per plate were tested per day, and each genotype or condition was assayed in at least two independent experiments. As locomotion measurements were conducted using an automated algorithm, genotypes were not blinded prior to analysis.

Aggregation and bordering behavior

L4 animals were picked to a fresh plate 24 h before the assay. Sixty animals were then repicked to the assay plate (an NGM plate seeded 2 days earlier with 100 μL of E. coli OP50), and bordering and aggregation was scored 2 and 6 h later. The scorer was blind to genotype. Behavior was always scored on 2-4 assay plates (each containing 60 animals) per day and tested in at least two independent experiments.

Salt-based associative learning

Gustatory plasticity was tested as described (Beets et al., 2012, Hukema et al., 2008), in a climate-controlled room set at 20°C and 40% relative humidity. Synchronized young adult hermaphrodites were grown at 25°C on culture plates seeded with E. coli OP50. Animals were collected and washed three times over a period of 15 min with chemotaxis buffer (CTX, 5 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 6.6, 1 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM CaCl2). Mock-conditioned animals were washed in CTX buffer without NaCl, whereas NaCl-conditioned animals were washed in CTX containing 100 mM NaCl for salt conditioning. Salt chemotaxis behavior of mock- and NaCl-conditioned animals was then tested on four-quadrant plates (Falcon X plate, Becton Dickinson Labware) filled with buffered agar (2% agar, 5 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 6.6, 1 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM CaCl2) of which two opposing pairs have been supplemented with 25 mM NaCl. Assay plates were always prepared fresh and left open to solidify and dry for 60 min. Plates were then closed and used on the same day. After the washes, 50 - 150 animals were pipetted on the intersection of the four quadrants and allowed to crawl for 10 min on the quadrant plate. A chemotaxis index was calculated as (n(A) – n(C)) / (n(A) + n(C)) where n(A) is the number of worms within the quadrants containing NaCl and n(C) is the number of worms within the control quadrants without NaCl. The scorer was blind to genotype.

Selection-based QTL mapping

Competition assays

The C. elegans strains JU1249 and JU2825 were competed for several generations using different transfer methods. At the start of the assay, ten JU1249 and JU2825 L4 larvae were put together on a 10 cm NGM plate seeded with E. coli OP50. Five biological replicates were maintained at 23°C. Before the cultures starved, a small fraction of the population (200 to 400 animals) was used to seed a fresh culture plate. In Treatment A, the worms were harvested with M9 buffer and 2 μL of worm pellet was transferred to the next plate. In Treatment B, an agar cube (chunk) was cut at the edge of the bacterial lawn and deposited onto the next plate. After each transfer, the remaining animals were stored in M9 buffer at −80°C to quantify the relative proportions of JU1249 and JU2825 alleles.

The genomes of JU1249 and JU2825 were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq4000 at 20x coverage with paired-end 150 bp reads. For each genome, the raw data were aligned to the reference genome (C. elegans WS243 masked from http://wormbase.org) and analyzed using BWA, SAMtools, Picard and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (Li and Durbin, 2009, Li et al., 2009, Van der Auwera et al., 2013). The accession number for the genomic sequence data of JU1249 and JU2825 is NCBI: PRJNA514933 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=PRJNA514933).