Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore the dyadic experience of caring for a family member with cancer. Particular attention was given to examine the relationship between dyadic perceptions of role adjustment and mutuality as facilitators in resilience for posttreatment cancer patients and family caregivers.

Method

For this convergent parallel mixed methods study using grounded theory methodologies, 12 dyads were recruited from the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Qualitative data collection focused on social interactions between cancer patients and their family caregivers to better understand and describe how post-treatment patients and caregivers create mutuality in their relationships, how they describe the processes of role-adjustment, and how these processes facilitate dyadic resiliency. Quantitative data collected through electronic survey included the Family Caregiving Inventory (FCI) for Mutuality Scale, Neuro QoL Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, and Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities-Short Forms, and Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC).

Results

Eleven participants were spouses. Twenty-two self-reported as Caucasian. The sample ranged from 35–71 years of age (Caregiver M=53.7, Patient M=54.3). Most of the caregivers were female (n=8; 66.7%) and most of the patients were male (n=9; 75%). Qualitative interview data illuminated two primary psychosocial processes relating to resilience, role adjustment and mutuality as key facilitators for transformation and growth within dyadic partnerships coping with the challenges of cancer treatment and cancer caregiving.

The FCI-mutuality score for patients (M=3.65±0.47) and caregivers (M=3.45±0.42) reflected an average level of relationship quality. Relative to participation in, and satisfaction with social roles and activities, patients (M=50.66±7.70, M=48.81±6.64, respectively) and caregivers (M=50.69±8.6, M=51.9±8.75, respectively) reported scores that were similar to the US General Population (M=50±10).

Conclusions

New patterns of role adjustment and mutuality can assist with making meaning and finding benefit, and these patterns contribute to dyadic resilience when moving through a cancer experience. There are few interventions that target the function of the dyad, yet the emergent model identified in this paper, provides a direction for future dyadic research. By developing interventions at a dyadic level, providers have the potential to encourage dyadic resilience and sustain partnerships from cancer treatment into survivorship.

Keywords: Family Caregiver, Oncology, Dyad, Mutuality, Role Adjustment, Relationship, Resilience, Benefit, Mixed Methods, survivorship

1. Introduction

While diagnosis, treatment and survivorship of cancer has a tremendous effect on patients, the experience also has a profound influence on patients’ spouses and/or family, as many cancer patients are reliant on the care provided by their loved ones (Tolbert et al., 2018). In the United States alone, approximately 43.5 million family members provide support for individuals coping with illness, undergoing cancer treatment, and navigating the logistical and financial stressors of medical care (National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) in Collaboration with AARP, 2015). Research suggests that loved ones provide approximately $450 (€402) billion a year in uncompensated services, as well as significant amounts of time and energy, making family caregiving a major public health concern, and a federal research priority (Feinberg et al., 2011; Kent et al., 2016; Institute of Medicine, 2013).

Previous studies focused on family caregivers reveal that this burden can lead to role strain and stress, increasing caregivers’ own risks for morbidity and mortality (Geng et al., 2018; Stenberg et al., 2010; Vitaliano et al., 2003). Caregiving tasks drain caregivers of physical, emotional, social, financial and spiritual reservoirs (Biegel et al., 1991; LeSeure & Chongkham-Ang, 2015). As a consequence, caregivers often experience similar physical and mental health outcomes as cancer patients (Hagedoorn et al., 2008). While some initial interventions focused on approaches to individual stress reduction, skill building and education to increase caregiver preparedness, researchers have shifted from the conceptualizing of cancer as an illness experienced by two discrete individuals (e.g. patient and caregiver) to a “relational event” (Miller & Caughlin, 2013) through which the care recipient and caregiver share a co-created experience.

Analytic models utilizing cancer care recipient-caregiver dyads allow researchers to elicit perspectives from both patient and caregiver to better understand the interrelatedness of the cancer experience (Fletcher et al., 2012). As the couple or patient/family member pair come to function as a unit for cancer treatment negotiation, interpersonal emotional support and logistical care coordination, the dyadic pair affect one another’s quality of life (QoL) and psychological adjustment (Hagedoorn et al., 2008; Tolbert et al., 2018). These life altering events catalyze role negotiation, and a new “dyadic identity” emerges as they manage shared stress and make meaning out of mutual trauma (Badr et al., 2010; Gibbons et al., 2014).

Many dyadic projects highlighted relational function with regards to emotional distress or other negative manifestations of stress in the process of designing interventions to bring immediate improvements to patient and caregiver QoL (Li & Loke, 2014). Yet this narrow focus led to the inadvertent, if frequent, neglect of the more positive aspects of dyadic function, such as an emergent and shared sense of meaning and purpose, improved family relationships (Li & Loke, 2013), and a positive connection between strong relational identity and individual coping (Ahmad et al., 2017). These positive outcomes have the potential to provide relevant information for researchers developing supports to help patients and caregivers develop resilience across the diagnosis and stressful treatment trajectory, yet little is understood about what makes dyadic partnerships successful.

Some studies indicate that more successful dyadic relationships have achieved what researchers term “mutuality” (Altschuler et al., 2018). Lewis and colleagues (2008) define mutuality as “the extent to which the couple shares the same meanings, attitudes and orientation” toward the illness and demonstrates interpersonal sensitivity to the degree that one partner “is aware of the other partner’s feelings and thoughts”. Although understudied with regards to dyadic cancer experiences, there is evidence that low mutuality is a predictor of caregiver morbidity from role strain and burden, whereas high mutuality confers protective effects to one or both partners over time, often increasing dyadic confidence during periods marked by uncertainty and suffering (Park & Schumacher, 2014). This study examines the link between dyadic perceptions of role adjustment and mutuality as facilitators in resilience for posttreatment cancer patients and family caregivers.

2. Methods

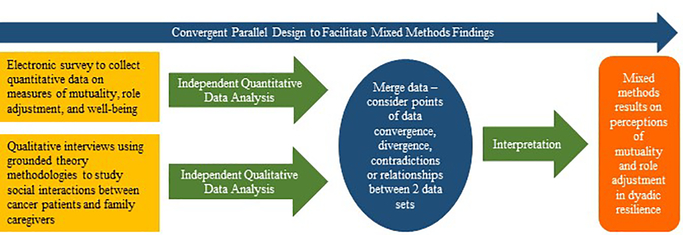

This project aimed to gain insight into, and describe concepts relating to, the dyadic experience of caring for a family member with cancer. We conducted a Convergent Parallel mixed methods study using grounded theory methodologies focused on human social and psychological processes made apparent through social interactions between cancer patients and their family caregivers (Blumer, 1962, 1969; Carter & Fuller, 2016; Guetterman et al., 2019).

2.1. Setting and Sample

We recruited a purposive sample of 12 dyads (e.g., cancer patients and their family caregivers) (n=24) from 32 dyads visiting an oncology ambulatory clinic at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (NIH CC) in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Patient participants and their designated family caregivers were eligible if they were: in a family caregiving situation for at least 6 months, age 18 or older, and at least six weeks from completing cancer treatment. Both the patient with cancer and caregiver had to be fully aware of the diagnosis and treatment, able to participate in a verbal interview, and able to read and write English. Once potential participants were identified and deemed eligible, an investigator explained all study procedures and provided a copy of the written consent form. Eligible dyads were invited to contact the study team if they wanted to participate. Of the 12 patients, ten had recently completed their third treatment for recurrent disease. One participant who lived with an unknown diagnosis for 39 years, had undergone a bone marrow transplant, their first “oncologic treatment.” Another patient with a cancer recurrence after 14 years underwent a second treatment.

2.2. Data Collection and Methodology

We utilized a Convergent Parallel Design to prioritize qualitative and quantitative methodology equally. Qualitative data and quantitative survey data were collected concomitantly, ensuring that electronic surveys were completed within 7 days of the qualitative interview participation. Prior to study initiation, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the investigators’ affiliated institutions ().

2.2.a. Qualitative data collection

A focused interview guide was used to ensure consistency of topics during the interviews. Participants chose the time and place to be interviewed, either in person in a private room within the hospital or by phone. Patients and caregivers were interviewed individually and only once. Individual interviews lasted from 30 to 90 minutes. Each participant was asked: a) What has this cancer illness experience been like for you? b) What is the communication like between the two of you? c) Describe how your family member’s illness/disease changed/influenced the way you interact with each other. d) Please describe adjustments or changes (e.g. in roles) you have made to be involved in your family member’s care. Further probes were employed to gain deeper insight into issues discussed.

All interviews were conducted by an principal investigator who worked with another investigator to organize and analyze data for interpretation. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.2.b. Quantitative data collection

Participants completed an electronic survey including socio-demographic questions, measures of mutuality [Family Caregiving Inventory (FCI) for Mutuality Scale], role adjustment (Neuro QoL Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, and Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities-Short Forms), and Well-Being (Mental Health Continuum-Short Form). The following measures were administered:

The FCI Mutuality Scale instructs participants to select the extent to which they agree with each of the provided statements addressing the quality of a relationship using a 5-point Likert Scale. A total of 15 items addressed the relationship dimensions of reciprocity, love, shared pleasurable activities, and shared values among the patient and caregiver. The average of all items across these four overarching themes produced a total mutuality score. Mean scores less than or equal to 2.5 were considered low mutuality (Archbold et al., 1990).

The Neuro-QoL is a multidimensional set of brief measures that evaluated symptoms, concerns, and issues for specific patient populations. The Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities assessed the degree of involvement in one’s usual social roles, activities and responsibilities, including work, family, friends and leisure. The Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities assessed the satisfaction with involvement in one’s usual social roles, activities and responsibilities, including work, family, friends and leisure. The score was standardized to a mean of 50 (SD 10). A higher T-score represented more participation and higher satisfaction in social roles and activities. The psychometric properties of these measures are well established (WWW.NEUROQOL.ORG).

The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) which consists of 14 items chosen from the MHC-Long Form as the most prototypical items representing the construct definition for each facet of well-being. Three items represented emotional well-being, six psychological well-being, and five social well-being. The response option for the short form measured the frequency with which respondents experienced each symptom of positive mental health, and thereby provided a clear standard for the assessment and a categorization of levels of positive mental health similar to the standard used to assess and diagnose major depressive episode in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Keyes, 2007).

2.3. Data Analysis

As warranted in Convergent Parallel research, quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed independently; then both sets were merged for analysis and overall interpretation (see Figure 1). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, measures of central tendency [mean with standard deviations or median with range]) and comparisons were computed for quantitative data. For qualitative analysis, investigators met after every 2–4 dyadic interviews to summarize key and recurring points from interviews and field notes. The investigators reviewed interviews using constant comparative analysis to derive conceptual and in-vivo codes, compare codes to one another, derive conceptual categories, and relate categories to codes and to other categories. Coding strategies included: open coding of words and phrases to capture meaning and render codes into conceptual categories, axial coding to delineate relationships between conceptual categories, and selective coding to integrate, refine and identify the main theme of the research. During these sessions, decisions were made to guide further data collection to capture details of primary concepts (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Theoretical saturation occurred when the pre-determined core categories were linked to subcategories, and information became redundant (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Figure 1.

Research design.

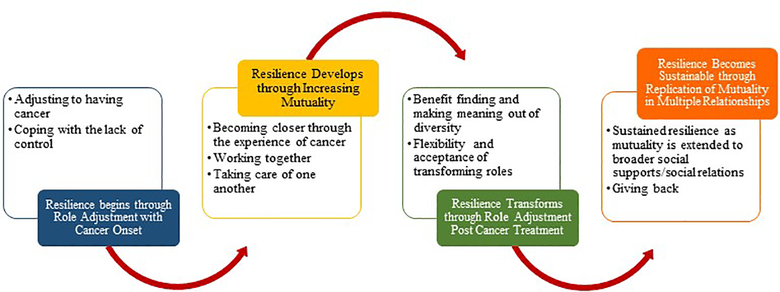

Four criteria were used to ensure trustworthiness of the study results (Speziale et al., 2011). Dependability and confirmability were achieved through on the spot validation, triangulation of interviews with self-report instrument results, and an audit trail and transparent processes that transformed interviews to findings. Study participants were asked to validate the final report and ensure credibility of study findings. Transferability and “fit” of theoretical rendering was achieved through translation of results for practicing nurses who care for similar groups of patients with cancer (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). In the final phase of analysis, family dyadic caregiving study participants were asked to review and to critique the validity of our emerging theory (see Figure 2). Categories developed in this study were also validated with current literature on individual and family resilience (Southwick & Charney, 2018; Walsh, 2016). Comparisons between our results and current views on individual and family functioning when dealing with adversity revealed evidence of sub-categories and strategies used by study participants.

Figure 2.

An Emergent Model for Building Dyadic Resilience for Cancer Patients and their Family Caregivers

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Of the twelve dyads that participated, eleven were spouses and the other a brother sibling dyad. Twenty-two self-reported as Caucasian, one patient as ‘Other,’ and the sibling dyad as African American. The sample ranged from 35–71 years of age (Caregiver (CG) M=53.7 SD=10.2, Patient (PT) M=54.3 SD=12.2)). Most of the caregivers were female (n=8; 66.7%) and most of the patients were male (n=9; 75%). Except for one patient, all participants had completed a high school education. The sibling patient lived alone, while 7 patients (58.3%) lived with spouse/partner and 4 (33.3%) with spouse/partner and dependent children. The time between end of treatment and study participation ranged from 6 weeks to 2 years. Demographic information can be found in Table 1, and information regarding patient diagnosis and treatment in Table 2.

Table 1:

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Caregiver (n=12) | Patient (n=12) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age, Mean (SD) min-max | 53.7 (10.2) (40–71) | 54.3 (12.2) (35–61) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4 (33) | 9 (75) |

| Female | 8 (67) | 3 (25) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 11 (92) | 10 (83) |

| African American | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| Other | 1 | |

| Education Levela | ||

| 9–12th Grade | 0 | 1 (8) |

| High School Graduate | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Some College | 2 (17) | 4 (33) |

| Associates Degree | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2 (17) | 5 (42) |

| Graduate or professional Degree | 6 (50) | 1 (8) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married or Partnered | 11 (92) | 11 (92) |

| Single or Never Married | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| Living Arrangements | ||

| Alone | 0 | 1 (8) |

| With Spouse/Partner Only | 8 (67) | 8 (67) |

| With Spouse/Partner and Dependent Children | 4 (33) | 2 (17) |

| Relationship to Caregiver/Patient | ||

| Spouse/Partner | 11 (92) | 11 (92) |

| Sibling | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| As a Caregiver/Patient, are you receiving additional help from: | ||

| Family | 1 (8) | 2 (18) |

| Friend | 1 (8) | |

| Multiple Others | 5 (42) | 3 (27) |

| None | 5 (42) | 6 (55) |

| Length of Caregiving (Caregiver Only) | ||

| 19–36 months | 2 (17) | |

| 37–48 months | 3 (25) | |

| 5 years or longer | 7 (58) | |

| Average # of days/week providing care/support (Caregiver Only) | ||

| 0–4 | 3 (25) | |

| 7 | 9 (75) | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 4 (33) | 3 (25) |

| Part-time | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Not Working (Disabled, Unemployed, Retired) | 6 (50) | 8 (65) |

| If working: Hours per week, Mean (SD) | 32.6 (19.9) | 35 (13.5) |

| Has he cancer or caregiving experience affected your ability to work?a | ||

| Yes (work less hours/left job) | 8 (67) | 2 (18) |

| No | 4 (33) | 9 (82) |

| Household Income | ||

| $ 10,001–$ 29,999 | 1 (8.3) | 0 |

| $ 30,000–$ 49,999 | 0 | 2 (17) |

| $ 50,000–$ 69,000 | 0 | 1 (8) |

| $ 70,000– $ 89,999 | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| $ 90,000–$ 149,998 | 5 (42) | 5 (42) |

| More than $ 150,000 | 2 (17) | 0 |

| Declined | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| Do you need help with finding resources? | ||

| Yes | 4 (33) | 4 (33) |

| No | 8 (67) | 8 (67) |

| Do you need financial assistance? | ||

| Yes | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| No | 10 (83) | 9 (75) |

NOTE:

n, declined to answer.

Table 2:

Patient (n=12) Clinical Characteristics

| Question | |

|---|---|

| How long have you had the current diagnosis? | |

| 7–12 months | 2 (17) |

| 13–24 months | 2 (17) |

| 25–36 months | 2 (17) |

| 37–48 months | 1 (8) |

| About 5 years or longer | 4 (33) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Acute Leukemia | 1 (8) |

| Lymphoma | 4 (33) |

| Non-Hematologic Condition | 1 (8) |

| Solid Tumor | 6 (50) |

| Initial Treatment | 2 (18) |

| Treatment Type | |

| Stem Cell Transplant | 5 (42) |

| Cellular Therapy (non-transplantation) | 6 (50) |

| Surgical Plus Hormonal | 1 (8) |

NOTE:

n, declined to answer.

3.2. Role Adjustment and Mutuality as Keys to Resilience over the Course of Cancer Care

Qualitative interview data illuminated two primary psychosocial processes, role adjustment (at the onset of cancer and post-treatment), and mutuality (dyadic and in broader social relationships) as key facilitators for dyadic resilience and growth when coping with the challenges of cancer treatment and cancer caregiving. Within those primary themes, there are subthemes, indicated in the text by indentation and underlining. We have omitted verbal pauses (e.g. and, um, you know, etc.) to enhance readability, otherwise the quotes are represented verbatim.

3.2.a. Role Adjustment at the Onset of Cancer

Adjusting to Having Cancer

With the diagnosis of cancer, and onset of treatment, both patient and caregiver engaged in role adjustment. As the majority of patients were generally feeling well at the time of the interviews, and their caregivers were withdrawing from their active roles as caregivers, their responses were reflective about the overall journey. In the treatment phase of cancer, patients recognized their need to be self-centered. One referred to this as being in the “take mode,” while another said he became the “hub”. These feelings were not always comfortable for the patients. One noted that it was “hard” existing in the unknown; not able to see “beyond getting through each day”. Another acknowledged “guilt” towards his spouse as a result of the social restrictions brought on by his cancer treatment. Even so, patients understood the need to focus on ‘self’ as a necessity of cancer treatment. A patient articulated,

“My primary role is taking care of myself and getting better. That’s very important to me right now…when you’re trying to get better, all of that takes precedence over all those other things”.

Caregivers’ noted the need for role adjustment as well. One indicated that her personal priorities changed drastically, saying, “It’s all relative. What used to be important, before the illness, is less important now”. Others described their caregiver roles as a “big adjustment”, “life-altering”, and “time-consuming.” Some had to “learn how to deal with it.” One man mentioned how this changed his employment, as he could no longer work in the way he had previously while still caring for his wife.

“Tele-work ended for me about three years ago with the government shut down. The people I worked for wouldn’t let me tele-work anymore and I couldn’t do my job and take care of [Spouse’s Name]. So, I retired. So, it changed. I enjoyed work. I enjoyed what I was doing. But [Spouse’s Name] and her care became more important.”

A wife mentioned how her husband’s cancer affected his work, self-concept as a provider, and eventually their sex life. In general, caregivers reported the need to slow the pace of their lives so that the patient could recover.

Coping with a Lack of Control

The subtheme of coping with the lack of control brought about by cancer was pervasive across all situations in the illness experience for both patients and caregivers. Participants cited necessary adjustments due to restrictions imposed by the illness and the medical establishment, the liminality of living with the unexpected, and grappling with thoughts of their own death or the possible death of a partner or spouse.

Patients and caregivers were emotionally strained from their experience. Some expressed mutual suffering, anger about their current situation, and uncertainty about the future. As patients were fighting for their lives, they spoke of “being chained to the hospital” and were frustrated with the ambiguity. One patient spoke of having to “track” his future to make sure he does not, “look beyond a point that [he] can deal with”. A woman discussed her attempt to control the uncontrollable by helping her husband “check out who [his] future spouse might be”. The conversation did not go over well, and the wife admitted with some degree of humor that “He got really mad” and said “flat out…we will not discuss this” although she continued to “look around”.

The inability to plan day to day and move forward with life goals led couples to creatively cope with negative emotions. One caregiver took an existential perspective in order to feel in control of his destiny, “We didn’t talk about my anger.” When they did, however, he tried to do it “as lovingly” as possible. He acknowledged his struggle to cope with his resentment, indicating that it was not his wife’s “fault” that the cancer happened.

Although the role adjustments stemming from this lack of control had the potential to strain the dyadic relationship, couples more often spoke of coming together with situations they faced as opposed to moving apart. The wife who had mentioned sexual strain due to cancer, said, “We hold hands all the time. We have a loveseat we sit on together…physical closeness…is important to us”. The husband who spoke of his resentment, amended, we try

“not to let the anger about what has happened stand in the way of being as loving to each other as we possibly can. Because in that way we transcend. That is our power”.

A sufficient number of dyads mentioned the need to make sure that adjustments were agreeable to both partners. This discussion itself, and the role negotiation appeared to help the overall process of dyadic resilience.

3.2 b. Role Adjustment Post Cancer Treatment

Adjusting to Post Treatment Realities and Transforming Roles

While much of the data collected, focused on adjusting to new roles during cancer treatment, some participants were candid about their changing roles at the completion of treatment as well. Caregivers’ discussed responsibilities in terms of being a “parent” who allowed the patient to feel in control. They functioned as illness manager, and filtered information to family and friends. Besides medication administration, transportation to appointments, and monitoring symptoms, caregivers helped patients “not be stuck” and “deal with life.” As the couples moved toward survivorship phase, patients’ needs lessened, and caregivers “weaned” themselves from their role in order to be a spouse or partner again. This back and forth experience is described by a caregiver:

“I wasn’t letting him because I was supposed to be in charge. And he was like, what are you doing? I’d like to go for a walk. And I’d say, Well, you can’t walk without me. And he’s like, I’ll go without you. [I’d respond], No. You can’t, because if you fall then it’s my fault because I’m the caregiver. And he’s like, This is weird.

The caregiver acknowledged that the awkwardness of the role transformation lasted for “about 30 days, and ended when her daughter said, “Mom, I don’t think its dad. You’re just being overbearing”.

Benefit Finding and Meaning Making Out of Adversity

Interviews also revealed much about how dyads engaged in benefit finding and meaning making. This process was expressed in various unique ways in the data of participating couples. Patients told us that cancer was “life changing,” and that they felt they had “gained more than they had given up”. Another said, “[Cancer] gives life a little more meaning; a little bit more value”.

Caregivers too noted how “priorities change as a result of cancer”. Both patients and caregivers alluded to “we” as opposed to “me” in relation to important decisions and experiences. One husband whose wife refused another course of chemotherapy because of the negative influence it had on her quality of life, listened to his wife’s wishes.

“My wife wanted to find something that would make her own body fight against this and cure it. So we are going to look at immunotherapy plans.”

Many examples like this were shared by participating couples who eventually moved past the acute phase of treatment and toward their new lives with renewed purposes and goals. As they reflected back on what had happened, they sought the “silver lining,” those moments that made things better, brought value to relationships, inspired new appreciation for life. Caregivers spoke of how cancer changed them personally, made them better people—more compassionate and more in tune to humanity. Caregiver perspectives included salient points such as “change after treatment breathes new life into the family,” “I’m thrilled (the cancer) happened,” and “It was a significant emotional event that catapulted us to a better life”.

3.2.c. Increasing Mutuality

Becoming Closer

Successful dyadic partnerships discussed ways in which the adversity they faced through cancer caused them to become closer. They mentioned remaining mindful of strategies such as “loving each other,” “admiring and valuing one another,” and “unquestioningly committing to the illness experience.” Some mentioned that their affection for one another deepened. One patient told us:

“…sometimes if I get upset in the relationship…I can’t question her love for me in ways because I think about all she’s done throughout the cancer diagnosis and treatment that she selflessly did so much…which just shows me how much she really cares.”

Caregivers saw the commitment they made to care for their loved ones as an expectation of their relationship (i.e. “what you do for someone you love). Nearly all expressed that there was “no choice in the matter.” One caregiver said, “It probably brought us closer, a level of respect…he absolutely makes it easy for me to care”. Another said, “I’m just doing what I know he would do for me”. Other dyads noted how spirituality and prayer could help them feel closer. One patient discussed unexpected ways in which the acute treatment period of the cancer experience brought him and his partner together as a chaplain helped them pray.

“After the surgery, they have a chaplain that goes around; she was wonderful. She came in there and was talking to me, [Spouse’s Name] and her dad. And [Spouse’s Name] and her dad are Jewish. But the chaplain is for all faiths and she seems to have a really good understanding of all faiths. She was just an amazing person to talk to. And, I’m not usually someone who would be intrigued by that at all. She actually got us to pray together, like we wanted to, which is odd because me and [Spouse’s Name] have never done that.”

Working together

As the mutuality increased during the illness journey, patients and caregivers noted that the intimacy in their relationships grew. Dyads expressed their experiences of suffering together, working together, and communicating. Patients mentioned that they felt that caregivers “understood” their struggles battling cancer. One patient said of her relationship, “We just kind of are one in many ways;” a statement echoed by her spouse,

“Together, we have been discovering these new levels of chaos and trauma, but that’s been great because we’ve both learned how to deal with them…symbiotically.”

Patients described synergy in the collaboration both verbally and non-verbally. Communication improved because it had to. One patient told us, “We realize that it’s more important that we talk about how you’re feeling … more essay-type questions as opposed to multiple choice”. Another claimed, “We just kind of spring into action. That’s how we work. We don’t even have to talk sometimes. We communicate by some other means”.

Taking Care of One Another

Dyads saw themselves as a caregiving team. As a member of that team, they supported one another emotionally. Patients remarked that caregivers kept their spirits up and, in some instances, the caregivers’ presence was enough to put the patient into a better mood. Caregivers acknowledged that they provided a lot of moral support and encouragement, both partners learning to express emotions openly.

Dyads also noted the need to “stay tuned into” their partner, “stay positive,” and “encourage one another to self-care.” Patients noted an increased ability to be in tune with the caregiver’s hopes and dreams for the future, whereas caregivers focused on the patient’s overall health and well-being. Even though their foci differed, the dyads were mutually protective of one another. One patient indicated, “We pick up each other’s strengths and weaknesses… we know that one of us has to be strong at all times. I mean it’s not good to have a bad day on the same day”. A caregiver added:

“I think [optimism] is good. I think it starts the day on a positive note, starting the day together, because we always end the day together.”

A caregiver, who said her primary role in life was “Joy Giver,” mirrored this sentiment, saying,

“I know in my heart, what I need to be doing is bring joy to [Spouse’s Name]…everything else will fall into place. Every day you find that bit of joy and there’s always one thing you can be thankful for, even on the crappiest days”.

Even so, many caretakers acknowledged the challenge of being open and honest with their partners regarding difficult emotions while trying to maintain a positive and supportive front. One caregiver told us, “It’s not like I want to hide anything from him, but…it’s a delicate balance”. Another admitted, “I could handle things better, be stronger.” But then went on to suggest, “…it’s important not to put up that façade, to show your weaknesses….it’s almost better for the patient to see them a little bit.” The caregiver also suggested that she shares these difficult emotion with her support people, saying, “I thinks it’s important that the kids see that…this stinks…this is life and death, but we can get through it”.

3.2.d. Dyadic Mutuality in Broader Social Relations

Awareness and Replication of Mutuality in Multiple Relationships

Patients and caregivers also found new roles through social networks like peer-to-peer discussions online and other social media that extended their reach to people with whom they otherwise would not have had contact. Many took advantage of online peer to peer group interactions because they learned about other people’s experiences. Study dyads found that access to internet, apps, and other electronic resources, simplified their learning about the illness and treatment options. They had the most recent cancer research at their fingertips.

Still, with the change in focus and intensity of the cancer experience, some dyads noted “evaporating relationships” because they were “not fun any longer.” Even though some relationships weakened and dissolved, others developed so that circles of friends expanded to include those who understood and those who worked to simplify dyads’ lives by helping with the many changes that come with a tumultuous cancer treatment situation. Caregivers, in particular, recognized that the cancer treatment experience had made them “more empathetic” and caused them to “appreciate people around them a whole lot more.” One caregiver said that her family was moving as a result.

“You have to appreciate the people that stand by you through this…and that is why we are moving. My family…the ones that were emotionally there for us. They’re in Florida. I want my son near that”.

Another spoke of others in similar situations he had met along the way, saying, “I’ve met all kinds of people that I probably never would’ve come across…and I appreciate that”. In these ways, the cancer experienced allowed caregivers to reinforce and value extant social support connections while building new social connections to sustain resilience post cancer.

Giving Back

Multiple participants praised the “unknown heroes in their [lives] like nurses and doctors.” Their growth in character and perspective garnered positive support from others, and led many to adopt altruistic roles so they were able to “give back.” A caregiver said:

It gets back to priorities. I’m doing a lot of peer work, both with our church and with the United Way [a charitable organization]. This has really helped me to continue to realize that you need to help other people because you get help, and it’s all about what can you do for someone else. Not because others do it, but because it’s the right thing to do. And if I can’t do it, what’s the purpose of it all, right?

Many interviews illustrated how cancer inspired altruism in patients and caregivers who worked independently and as a unit toward the greater good.

3.3. Survey Overview

Patients and caregivers reported similar scores for FCI-mutuality, Neuro-QOL participation in, and satisfaction with, social roles/activities, and total MHC (p>0.05). The FCI-mutuality score for patients (M=3.65±0.47) and caregivers (M=3.45±0.42) reflected an average level of relationship quality. Relative to participation in, and satisfaction with social roles and activities, patients (M=50.66±7.70, M=48.81±6.64, respectively) and caregivers (M=50.69±8.6, M=51.9±8.75, respectively) reported scores that were similar to the US General Population (M=50±10) (WWW.NEUROQOL.ORG). The majority of the dyads (58%, n=7) reported congruence relative to their mental health: 2 dyads (29%) were flourishing, 4 (57%) were moderate, and only 1 dyad (14%) was languishing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Building Dyadic Resilience

The findings from this study build on existing evidence, albeit limited, of the dyadic experience when caring for a family member with cancer. A dyadic experience that ebbs and flows across the course of cancer treatment was well described in this study and is similar to the experience previously described by couples experiencing breast cancer (Keesing et al., 2016) and a stroke (Lopez-Espuela et al., 2018). An important point to consider when a study describes the dyadic experience with certain cancers, e.g. breast cancer, is the influence of gender (male caregivers) that can impact the generalizability of the findings when a different relationship match exists (female caregivers). Additionally, the acuity level of the patient may impact the dyadic experience. The dyads in the current study were beyond their active treatment phase and reported good communication. During a more acute phase of an illness, the dyadic experience can be quite different with a breakdown in communication or other challenges that can degrade their relationship (Wawrziczny et al., 2019). Communication is an important aspect of dyadic-based interventions yet more evidence is needed to optimize their dialogue and the effectiveness of the intervention (Badr, 2017).

In the current study, building dyadic resilience throughout the cancer experience was influenced by multiple interrelated factors, much like that described by caregivers of patients with Dementia (Teahan et al., 2018). Generally, the mere presence of a family caregiver across the cancer trajectory can have a positive impact on the patient’s life and the adoption of healthier habits (Litzelman et al., 2017). Relational mutuality was an additional factor in the current study and has been associated with positive dyadic outcomes during cancer (Kayser & Acquati, 2018) and heart failure (Vellone et al., 2018). The importance of benefit-finding was also well described in this study and supports existing evidence that highlights its importance in cancer care (Li et al., 2018). This is also documented in spousal couples experiencing Parkinson’s Disease where greater perceived benefits are related to better marital quality (Mavandadi et al., 2014).

The presence of family resilience can foster positive outcomes in cancer patients leading to post-traumatic growth and improved quality of life (Li et al., 2019). In the present study the positive experiences associated with caregiving extended beyond the immediate dyad relationship and extended to others in the form of altruistic behaviors. This was a novel finding in this study that has not been previously described.

4.2. Role Adjustment, Mutuality, and the Significance of Converged Data

Those interviewed in our study demonstrated how individuals adjusted to roles multiple times throughout the cancer journey. Although the patient’s health status and their partner’s roles were not stable overtime, the dyads reported good relational mutuality and were socially well adjusted. For the cancer patient/caregiver dyads, these factors may be important mediators for dyadic resilience. The quantitative data suggest that even through the traumatic experience of cancer diagnosis and treatment, dyadic partners ‘reset’ their relationships, demonstrating mutuality scores consistent with the broader U.S. population, finding their status quo and connectedness. Even so, this is only a partial aspect of the dynamic.

While participants sought a level of ‘comfortable’ congruence, they not only maintained their connectedness but they also experienced transformation. Qualitative data revealed new patterns of role adjustment and mutuality that assisted them in finding meaning and benefits as they moved through a significant cancer treatment experience (see the Emergent Model for Building Dyadic Resilience, Figure 2). These patterns were indicative of expanded forms of resilience for both cancer patients and their caregivers.

4.3. Need for Integrated Dyadic Research

Recognition of the care recipient-caregiver dyad reveals a promising location for development of an integrated interventional support for both patient and caregiver, relocating research tendencies to focus on discrete individuals, instead, considering their interrelatedness (Miller & Caughlin, 2013). We suggest that the cancer experience provides a unique opportunity to build on the positive tendencies inherent in dyadic partnerships already engaging in role adjustment and mutuality development in the midst of uncertainty. By attending to the dyadic pair, and acknowledging the degree to which each effects the other’s quality of life, researchers can identify appropriate supports to help both work more effectively as a pair to manage both shared stress and traumatic experience (Badr et al., 2010; Gibbons et al., 2014).

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

As participants were drawn from the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, a research medical facility in the United States, the findings of our project may not be representative of other clinical settings in diverse locales (e.g. rural, impoverished, etc.). Further, we engaged participants using purposive sampling methods which may introduce researcher biases. Moreover, our sample was relatively small, and homogenous in terms of race/ethnicity, education and socioeconomic status. Additionally, the couples who agreed to participate were generally well-adjusted, while the couples who declined to participate may have been less well adjusted. However, our data highlight common elements of the cancer journey experienced by dyadic partners and offer important insights into the interplay of role adjustment and mutuality as key facets of resilience during intensive cancer treatment, and healthy reorientation to ‘normal’ life patterns post cancer treatment.

5. Conclusions

Diagnosis, treatment and survivorship of cancer effects interpersonal relationships, social networks, finances, and functioning of patients and their family caregivers. Still there are few interventions that target the function of the dyad formed between patient and their primary family caregiver. The psychological processes identified by our participants, and the emergent model identified in this paper, provide a solid foundation for future research. Findings from our study demonstrate how even the most successful partnerships suffer tremendous stress due to illness and changing life circumstances. By developing interventions at a dyadic level, researchers and medical research partners have the potential to encourage dyadic resilience and sustain partnerships from cancer treatment into survivorship.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of the Defense, or the United States government. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad S, Fergus K, Shatokhina K, & Gardner S (2017). The closer ‘We’ are, the stronger ‘I’ am: the impact of couple identity on cancer coping self-efficacy. J Behav Med, 40(3), 403–413. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9803-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler A, Liljestrand P, Grant M, Hornbrook MC, Krouse RS, & McMullen CK (2018). Caregiving and mutuality among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies: qualitative study. Support Care Cancer, 26(2), 529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3862-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, & Harvath T (1990). Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health, 13(6), 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Carmack CL, Kashy DA, Cristofanilli M, & Revenson TA (2010). Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol, 29(2), 169–180. doi: 10.1037/a0018165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H (2017). New frontiers in couple-based interventions in cancer care: refining the prescription for spousal communication. Acta Oncol. February;56(2):139–145. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambauer KZ, Zhang B, Maciejewski PK, Sahay N, Pirl WF, Block SD, & Prigerson HG (2006). Mutuality and specificity of mental disorders in advanced cancer patients and caregivers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 41(10), 819–824. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0103-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel DE, Sales E, & Schulz R (1991). Family caregiving in chronic illness: Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, heart disease, mental illness, and stroke. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H (1962). Society as symbolic interaction In Rose AM (Ed.), Human behaviora and social processes (pp. 179–192). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter MJ, & Fuller C (2016). Symbols, meaning and action: The past, present, and future of symbolic interactionism. Current Sociology. doi: 10.1177/0011392116638396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, & Strauss A (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, & Choula R (2011). The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; Retrieved from https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, & Schumacher K (2012). The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur J Oncol Nurs, 16(4), 387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng HM, Chuang DM, Yang F, Yang Y, Liu WM, Liu LH, & Tian HM (2018). Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 97(39), e11863. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons SW, Ross A, & Bevans M (2014). Liminality as a conceptual frame for understanding the family caregiving rite of passage: an integrative review. Res Nurs Health, 37(5), 423–436. doi: 10.1002/nur.21622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JM, Meis L, Greer N, Jensen A, MacDonald R, Rutks I, … Wilt TJ (2013). In Effectiveness of Family and Caregiver Interventions on Patient Outcomes Among Adults with Cancer or Memory-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review. Washington (DC). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guetterman TC, Babchuk WA, Howell Smith MC, Stevens J (2019). Contemporary Approaches to Mixed Methods–Grounded Theory Research: A Field-Based Analysis. J Mixed Methods Research. Volume: 13 issue: 2, page(s): 179–195. 10.1177/1558689817710877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, & Coyne JC (2008). Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull, 134(1), 1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2013). Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser K, & Acquati C (2019). The influence of relational mutuality on dyadic coping among couples facing breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. Mar-Apr;37(2):194–212. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2019.1566809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WY, Shelburne N, … Huss K (2016). Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer, 122(13), 1987–1995. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol, 62(2), 95–108. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Deci EL, & Kasser T (2008). Adult attachment and psychological well-being in cancer caregivers: the mediational role of spouses’ motives for caregiving. Health Psychol, 27(2S), S144–154. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Shaffer KM, Gansler T, & Cannady RS (2015). Cancer caregiving predicts physical impairments: roles of earlier caregiving stress and being a spousal caregiver. Cancer, 121(2), 302–310. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing S, Rosenwax L, McNamara B (2016). A dyadic approach to understanding the impact of breast cancer on relationships between partners during early survivorship. BMC Womens Health. 2016 August 25;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0337-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSeure P, & Chongkham-Ang S (2015). The Experience of Caregivers Living with Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. J Pers Med, 5(4), 406–439. doi: 10.3390/jpm5040406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis FM, Cochrane BB, Fletcher KA, Zahlis EH, Shands ME, Gralow JR, … Schmitz K (2008). Helping Her Heal: a pilot study of an educational counseling intervention for spouses of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology, 17(2), 131–137. doi: 10.1002/pon.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, & Loke AY (2013). The positive aspects of caregiving for cancer patients: a critical review of the literature and directions for future research. Psychooncology, 22(11), 2399–2407. doi: 10.1002/pon.3311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, & Loke AY (2014). A literature review on the mutual impact of the spousal caregiver-cancer patients dyads: ‘communication’, ‘reciprocal influence’, and ‘caregiver-patient congruence’. Eur J Oncol Nurs, 18(1), 58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Lin Y, Zhou H, Xu Y, Yang L, Xu Y (2018). Factors moderating the mutual impact of benefit finding between Chinese patients with cancer and their family caregivers: A cross-sectional study. Psychooncology. October;27(10):2363–2373. doi: 10.1002/pon.4833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Qiao Y, Luan X, Li S, Wang K (2019). Family resilience and psychological well-being among Chinese breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. Eur J Cancer Care. March; 28(2): e12984. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman K, Blanch-Hartigan D, Lin CC, Han X (2017). Correlates of the positive psychological byproducts of cancer: Role of family caregivers and informational support. Palliat Support Care. December;15(6):693–703. doi: 10.1017/S1478951517000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Espuela F, González-Gil T, Amarilla-Donoso J, Cordovilla-Guardia S, Portilla-Cuenca JC, Casado-Naranjo I (2018). Critical points in the experience of spouse caregivers of patients who have suffered a stroke. A phenomenological interpretive study. PLoS One. April 4;13(4):e0195190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavandadi S, Dobkin R, Mamikonyan E, Sayers S, Ten Have T, Weintraub D (2014). Benefit finding and relationship quality in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot dyadic analysis of husbands and wives. J Fam Psychol October;28(5):728–34. doi: 10.1037/a0037847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LE, & Caughlin JP (2013). “We’re Going to be Survivors”: Couples’ Identity Challenges During and After Cancer Treatment. Communication Monographs, 80(1), 63–82. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2012.739703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) in Collaboration with AARP. Caregiving in the US. 2015

- Northouse LL, Mood D, Kershaw T, Schafenacker A, Mellon S, Walker J, … Decker V (2002). Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. J Clin Oncol, 20(19), 4050–4064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EO, & Schumacher KL (2014). The state of the science of family caregiver-care receiver mutuality: a systematic review. Nurs Inq, 21(2), 140–152. doi: 10.1111/nin.12032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, & Charney DS (2018). Resilience: The science of mastering life’s greatest challenges (2nd ed). Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR, 2011. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative, 5th edition. Lippincott, Williams and Wilson. [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, & Miaskowski C (2010). Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology, 19(10), 1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teahan Á, Lafferty A, McAuliffe E, Phelan A, O’Sullivan L, O’Shea D, Fealy G (2018). Resilience in family caregiving for people with dementia: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. December;33(12):1582–1595. doi: 10.1002/gps.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert E, Bowie J, Snyder C, Bantug E, & Smith K (2018). A qualitative exploration of the experiences, needs, and roles of caregivers during and after cancer treatment: “That’s what I say. I’m a relative survivor”. J Cancer Surviv, 12(1), 134–144. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0652-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellone E, Chung ML, Alvaro R, Paturzo M, Dellafiore F (2018). The Influence of Mutuality on Self-Care in Heart Failure Patients and Caregivers: A Dyadic Analysis. J Fam Nurs November 19. doi: 10.1177/1074840718809484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, & Scanlan JM (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull, 129(6), 946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F (2016). Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. European Journal of Development Psychology, 13(3), 313–324. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2016.1154035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrziczny E, Corrairie A, Antoine P (2019). Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of dyadic dynamics. Disabil Rehabil. May 26:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1617794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]