Abstract

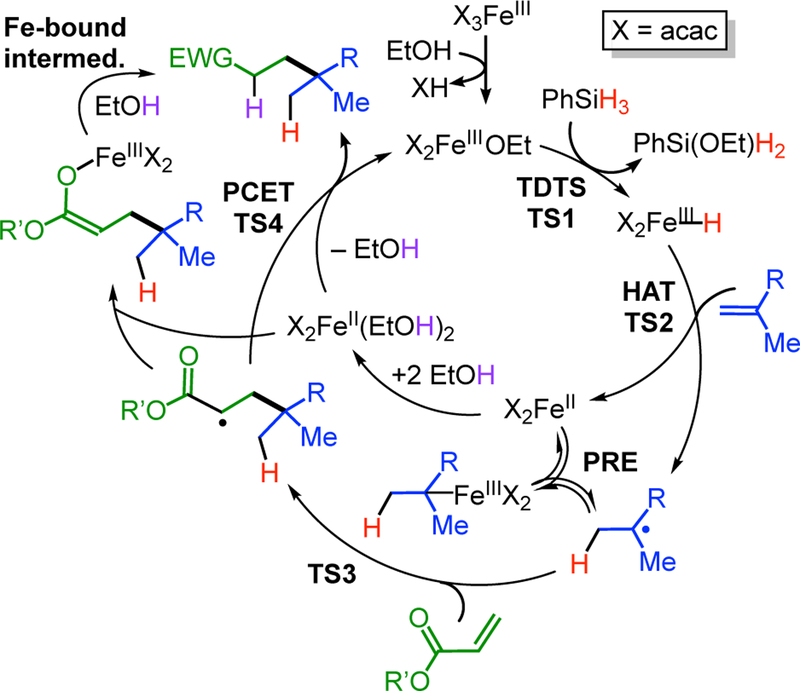

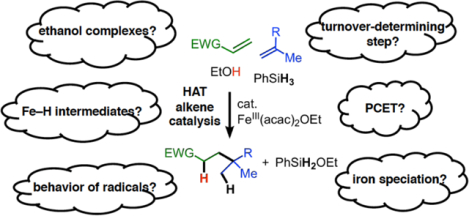

A growing and useful class of alkene coupling reactions involve hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from a metal-hydride species to an alkene to form a free radical, which is responsible for subsequent bond formation. Here, we use a combination of experimental and computational investigations to map out the mechanistic details of iron-catalyzed reductive alkene cross-coupling, an important representative of the HAT alkene reactions. We are able to explain several observations that were previously mysterious. First, the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle is the formation of the reactive Fe-H intermediate, elucidating the importance of the choice of reductant. Second, the success of the catalytic system is attributable to the exceptionally weak (17 kcal/mol) Fe-H bond, which performs irreversible HAT to alkenes in contrast to previous studies on isolable hydride complexes where this addition was reversible. Third, the organic radical intermediates can reversibly form organometallic species, which helps to protect the free radicals from side reactions. Fourth, the previously accepted quenching of the post-coupling radical through stepwise electron transfer/proton transfer is not as favorable as alternative mechanisms. We find that there are two feasible pathways. One uses concerted proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) from an iron(II) ethanol complex, which is facilitated because the O–H bond dissociation free energy is lowered by 30 kcal/mol upon metal binding. In an alternative pathway, an O-bound enolate-iron(III) complex undergoes proton shuttling from an iron-bound alcohol. These kinetic, spectroscopic, and computational studies identify key organometallic species and PCET steps that control selectivity and reactivity in metal-catalyzed HAT alkene coupling, and create a firm basis for elucidation of mechanisms in the growing class of HAT alkene cross-coupling reactions.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The alkene functional group is an inexpensive and versatile building block for biologically active molecular structures. However, the chemoselective functionalization of unactivated alkenes to generate highly substituted carbon centers is challenging, because traditional routes based on carbocations often suffer from side reactions.1 As a milder alternative, chemists have developed a class of transition-metal-catalyzed Markovnikov-selective hydrofunctionalization reactions for forming C–C, C–O, and C–N bonds from unactivated alkenes.1b, 2 These reactions have excellent functional-group tolerance, predictable regioselectivity, and experimental simplicity.3 The precatalysts are typically simple Mn, Fe, or, Co salts of halide, acac, or oxalate, and the reducing equivalents come from borohydrides or silanes.2, 4

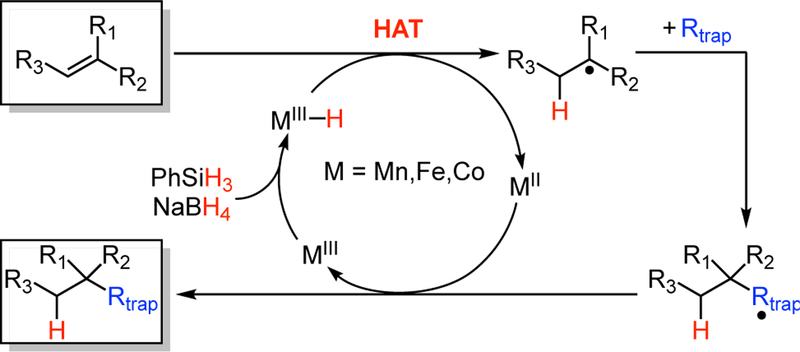

A general mechanism has been proposed for these reactions (Scheme 1), which features hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) to the alkene from a putative metal-hydride complex (M–H), which is generated in situ from a metal salt and a hydride source.1b HAT would generate a reduced metal species and the alkyl radical at the more substituted side of the original alkene. When this radical reacts with a trapping agent, the product is the Markovnikov product with a new C–C, C–N, or C–O bond. In many HAT alkene reactions, such as Co-catalyzed hydrohydrazination, Fe-catalyzed hydroamination, hydromethylation and alkene coupling, the product of trapping is another radical.1b According to the proposed mechanism, this coupled radical undergoes an electron transfer reaction with the metal byproduct, which oxidizes the metal to a form that reacts with borohydride or silane to regenerate the active metal-hydride.

Scheme 1. General Mechanism Proposed for Catalytic HAT Alkene Coupling Reactions.

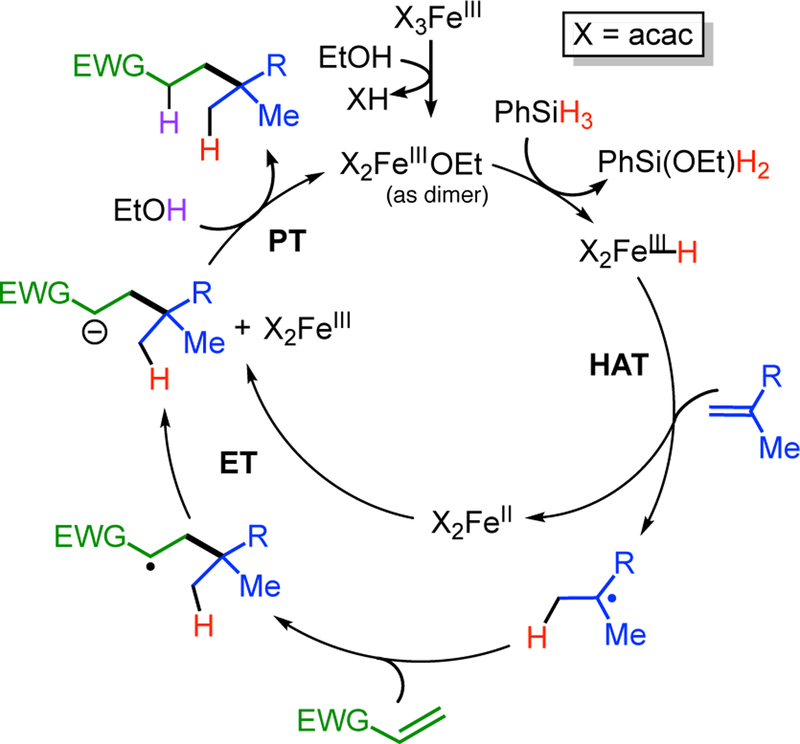

In this report, we focus on one specific HAT alkene reaction, the intermolecular cross-coupling of two alkenes. The catalytic cycle is proposed to follow the general pathway of Scheme 1, with an electron-poor alkene serving as the trap. This reaction was reported by Baran in 2014,5 and later publications demonstrated the reaction scope and utility in C-C bond constructions of synthetic relevance for natural products.6 This reaction uses Fe(acac)3 as a pre-catalyst and PhSiH3 as a reductant, and HAT catalysis was proposed to proceed through the iron(III)/iron(II) cycle shown in Scheme 2. It was presumed that the hypothetical iron(III) hydride selectively attacks the electron-rich “donor” alkene (blue in Scheme 2), giving an iron(II) species and a nucleophilic alkyl radical. This radical then is trapped by the electron-poor “acceptor” alkene (green in Scheme 2), and the formation of the new C–C bond generates a product with a radical adjacent to the electron-withdrawing group. In the final steps, this radical accepts an electron and a proton to generate product. Lo et al. concluded that this is a stepwise process proceeding through a carbanion for two reasons: (a) the use of EtOD solvent gives deuteration α to the electron-withdrawing group (shown in purple in Scheme 2), even though the ethanol O–H bond (104 kcal/mol)7 is stronger than the C-H bond that is formed, and (b) it was possible to perform a three-component coupling that adds an aldehyde a to the electron-withdrawing group.6b Below, we systematically evaluate a number of alternative mechanisms for this proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) pathway.

Scheme 2. Previously Proposed Mechanism for Iron-Catalyzed Intermolecular Cross-Coupling of Alkenes.

So far, this proposed mechanism lacks key tests of its veracity. In the alkene cross-coupling, as in all the catalytic HAT alkene reactions, no organometallic species or radicals have been observed. Detection of the metal-containing species in HAT alkene reactions in general is complicated by the lack of chelating supporting ligands to stabilize the intermediate metal complexes, and by the weak-field nature of halides, acac, and oxalate that render the metal sites high-spin and difficult to observe by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Broad peaks in 1H NMR spectra of a cobalt-catalyzed silylperoxidation reaction were tentatively assigned to a metal-bound hydride, but the interpretation of the data is ambiguous.8 In the iron-catalyzed HAT alkene cross-coupling, we took first steps toward identifying relevant metal species, by discovering that during catalysis both iron(II) and iron(III) acac complexes gave 1H NMR resonances that could be assigned by comparison with independently synthesized complexes.6b These measurements were complemented by 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy studies9 that showed that Fe(acac)2 is the reduced iron species and that [Fe(acac)2(μ-OEt)]2 is catalytically competent.6b However, there have been no systematic computational studies showing that the catalytic cycle as proposed in Scheme 2 is energetically feasible, or would give the observed selectivity.

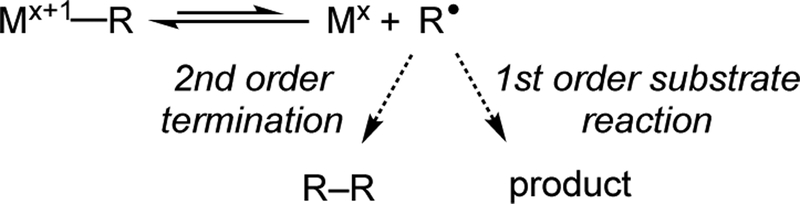

Another issue that has been proposed in the context of HAT alkene reactions1b, 3 is the persistent radical effect (PRE).10 In the PRE, the life of a reactive radical (normally susceptible to bimolecular self-termination) is extended by its engagement in an equilibrium with a high-concentration trapping species, usually having radical character (the “persistent radical”), thus lowering its concentration and hence the rate of bimolecular termination (Scheme 3). The PRE often leads to cross-selectivity of radical addition reactions,11 and similarly leads to the controlled polymerization of alkenes.10b The PRE can influence metal-catalyzed reactions through reversible trapping of a radical by a reduced metal (Mx) to form a metal-alkyl complex (Mx+1–R). If subsequent reactions take place only through the free radical, then the formation of the M-C bond “protects” most of the radical, lowering the concentration of the free radical. This effect has been used for controlling free-radical polymerization reactions by the approach termed organometallic-mediated radical polymerization (OMRP), in which metal-alkyl species are well documented.12

Scheme 3. The Persistent Radical Effect in Organometallic-Mediated Processes.

In the alkene cross-coupling reaction, we used NMR and Mössbauer spectroscopies to show that the vast majority of the iron (>95%) is present as reduced Fe(acac)2, which could in principle react with transient alkyl radicals to form an iron(III) alkyl species.6b Though these putative iron(III) alkyls were not observed by Mössbauer spectroscopy, their concentration could be too low to detect. In order to understand and control the HAT alkene reactions, it is important to evaluate the reactivity of such metal species, even when they are not experimentally observed. Here, we describe the results of mechanistic experiments and DFT computations that increase our understanding of several key steps in the HAT alkene cross-coupling by iron-acac catalysts. They illuminate unanticipated mechanistic features that are likely to be applicable to the broader class of HAT alkene reactions with Mn, Fe, and Co. Therefore, the results are likely to be useful for analysis and improvement of related reactions such as hydropyridylation (Minisci reaction), hydroamination, hydroazidation, hydrohydrazination, hydrocyanation, hydration, and hydrogenation.1b

RESULTS

Formation of the Reactive Hydride Species.

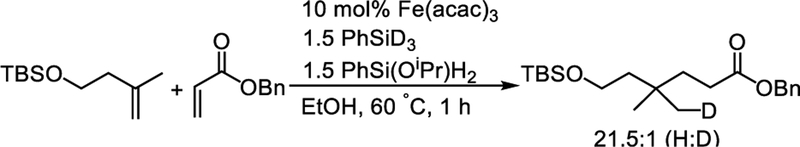

In our earlier paper6b we developed a new catalyst, [(acac)2Fe(μ-OEt)]2, which is much more active than the Fe(acac)3 precatalyst. Its higher activity was attributed to the ability of the ethoxide to react directly with silanes to give an iron hydride. It was interesting that the rate of the catalytic reaction depended on the hydride donor used: it was faster when using the monoalkoxysilane PhSi(OEt)H2, but slower using PhSiH3 or PhSi(OEt)2H. Obradors and Shenvi have described an analogous rate increase using PhSi(OiPr)H2.13 However, it was not clear whether this silane is a more active hydride donor, or whether the monoalkoxysilane somehow modifies the iron catalyst. To resolve this question, we performed the catalytic reaction with equal amounts of PhSiD3 and PhSi(OEt)H2. Product analysis by mass spectrometry showed that this reaction gave less than 5% deuteration of the product (Scheme 4 and Figure S25), which contrasts with the complete deuteration observed when PhSiD3 is used as the sole silane.14 This result demonstrates that the monoalkoxysilane more rapidly generates the reactive hydride that ends up in the product.

Scheme 4. A Competition Experiment Indicates That PhSi(OiPr)H2 Is More Reactive Than PhSiH3.

The reaction trajectory for hydride transfer with a slightly truncated model system [(acac)2Fe(μ-OMe)]2 was explored using density-functional theory (DFT) calculations with the BPW91* functional, which has been shown to be suitable for variable spin states for 3d transition metals.15 The geometries were optimized in the gas phase, and then the electronic energies were corrected for thermal (PV) and entropy (TS) effects at 298 K, dispersion forces, solvation in ethanol, and solution standard state (see Computational Details in the Supporting Information), to give standard-state free energies.

First, we resolved the electronic structure of the iron(III) alkoxide starting material. We considered all possible spin states for iron(III) (S = 1/2, 3/2, and 5/2, which are conventionally termed low-spin, intermediate-spin, and high-spin respectively). Details are in the Supporting Information (SI section 2.A). The calculations show that the dimeric starting material is most stable as an open-shell singlet (Stotal = 0), from antiferromagnetically coupled ions with local spins SFe = 5/2. The Stotal = 5 state lies only 0.3 kcal/mol higher, consistent with the weak antiferromagnetic coupling observed experimentally.16 Splitting into monomeric [FeIII(acac)2(OMe)] is feasible, since the two high spin monomer molecules are only 6.5 kcal/mol higher in energy than the dimer.

For the hydride product, we considered both monomeric and dimeric structures, since hydrides are often found to be bridging in iron compounds.17 In this case, the three monomeric spin isomers are calculated to be more stable than the corresponding dimers (SI section 2.B). The optimized structure of monomeric [FeIII(acac)2H] is spin state-dependent. The low-spin state has a square pyramidal geometry at iron with the strong trans-influence hydride in the axial position, while the intermediate-spin and high-spin states have trigonal bipyramidal iron with the hydride in the axial and equatorial positions, respectively. All three spin states have energies within 1.2 kcal/mol of one another. The dimeric species [(acac)2FeIII(μ-H)]2, in each spin state and with parallel or antiparallel spins on the two sites, were found to be higher in energy than the corresponding monomers by at least 5 kcal/mol. At catalytic concentrations of iron that are much lower than the standard state of 1 M, the dimer would be even more unfavorable. We also considered the potential for solvent ethanol to coordinate to a monomeric iron(III) hydride complex. However, the calculations show that binding of ethanol is weak: the octahedral EtOH adducts are not lower in energy in either the doublet or quartet state (SI section 2.C).

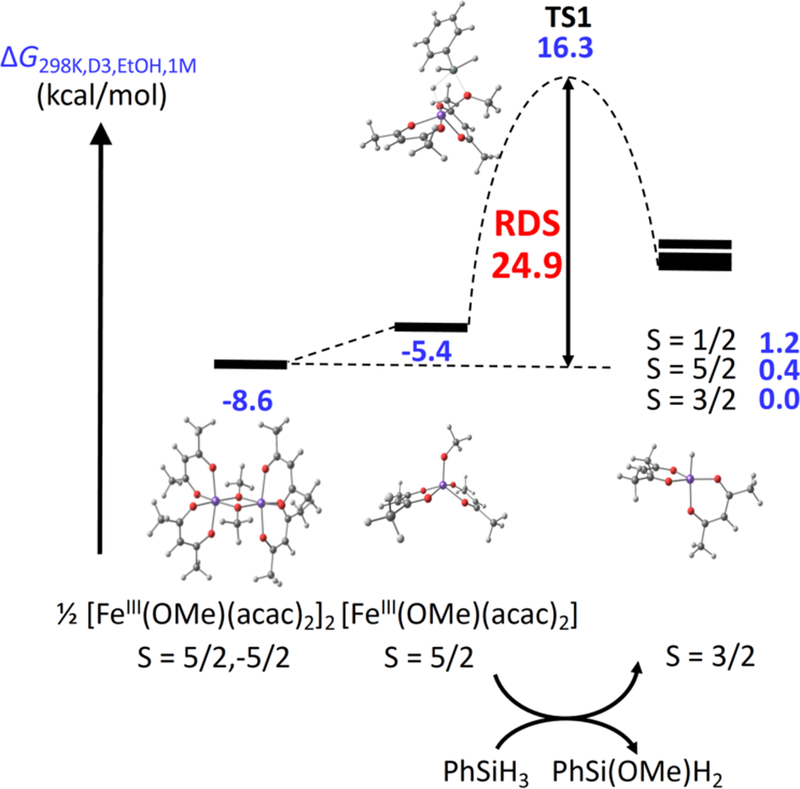

With the alkoxide and the hydride complexes modeled, we compared the thermodynamics and kinetics for hydride transfer from Si to Fe (details in SI section 2.D). The reaction of monomeric [FeIII(acac)2(OMe)] (S = 5/2) with PhSiH3 to form the aforementioned [FeIII(acac)2H] (S = 3/2) along with PhSi(OMe)H2 is uphill by 5.4 kcal/mol. Adding the energy of splitting the alkoxide dimer, the hydride product lies a total of 8.6 kcal/mol above the starting materials. The transition state for H transfer from PhSiH3 to Fe (TS1) on the sextet PES lies 24.9 kcal/mol above the starting materials (see Figure 1) in free energy. The corresponding TS along the quartet PES lies at a higher ΔG value (34.4 kcal/mol, see SI section 2.D). In light of the small barriers for other steps (see below), this alkoxide/hydride exchange is predicted to be the TOF-limiting step in the catalytic cycle. We measured the initial rate for the catalytic reaction at 40 °C to be 6.5±0.7 × 10−5 M/s, which leads to an estimate of the experimental ΔG‡ as 22.8 ± 0.2 kcal/mol. Thus, the computed barrier of 24.9 kcal/mol is similar to that observed experimentally.

Figure 1.

Relative energies of the starting materials (½ [FeIII(OMe)(acac)2]2 + PhSiH3), of the corresponding monomeric [FeIII(OMe)(acac)2] intermediate, and the reaction coordinate over TS1 to give [FeIIIH(acac)2] and PhSi(OMe)H2.

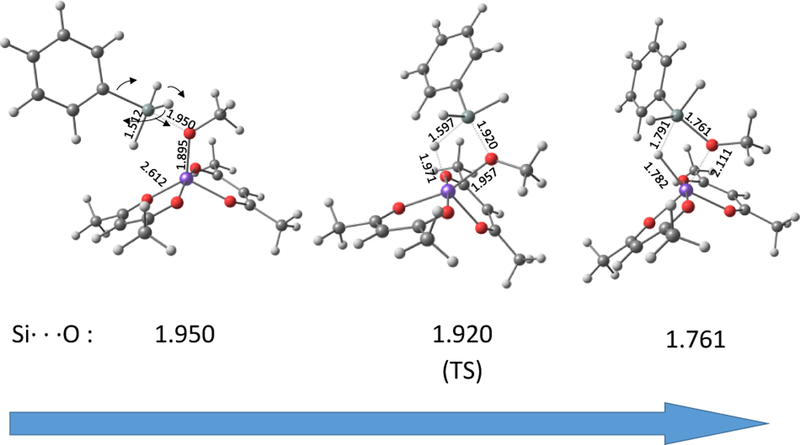

The calculated trajectory of this step is interesting (Figure 2). First, the iron-bound alkoxide approaches the Si atom opposite from the phenyl group (pseudo-trigonal bipyramidal with the incoming O considered as a bond). Then, the geometry at silicon undergoes a Berry pseudorotation to yield, at the transition state, a geometry close to an ideal square pyramid with a Si-H bond placed axially, and then eventually forms a new trigonal bipyramidal geometry with the transferring H atom and another H atom in the pseudo-axial positions, and the Ph and OMe substituents together with the third H atom in the pseudo-equatorial plane. From here, there is simultaneous transfer of hydride to Fe and OMe to Si to smoothly yield the products.

Figure 2.

Partially optimized structures (at fixed Si⋯O distances) of three representative points along the reaction pathway of precatalyst activation by PhSiH3.

The nature of this transition state helps to explain the greater activity when moving from PhSiH3 to PhSi(OR)H2. 6b, 13 The calculations, carried out with R = Me for simplicity, reveal a greater driving force for the alkoxysilane, as hydride transfer from the monoalkoxysilane is 4.1 kcal/mol less endergonic (SI section 2.E).18 This driving force comes from the greater hydridicity of the H atom (calculated Mulliken charges on the H atoms are −0.087 in PhSiH3, −0.118 in PhSi(OMe)H2 and −0.153 in PhSi(OMe)2H). The geometry of TS1 shows that one additional alkoxide group may be accommodated in the axial position of the square pyramidal geometry of the TS. Indeed, reoptimization of TS1 after replacement of one silane H atom with OMe gave a transition state corresponding to a barrier that is 3.6 kcal/mol lower in energy, which compares reasonably well to the ΔΔG‡ = 1.4 kcal/mol derived from the competition experiment in Scheme 4.14 However, use of the dialkoxysilane PhSi(OR)2H as hydride donor, even though presumably leading to a thermodynamically even more favorable transformation, would place an additional OR group in an equatorial position of the square pyramid where it would be destabilized by a steric clash with the other equatorial substituents. In this way, the computational investigation of the hydride transfer to the Fe atom elucidates the empirically observed silane trends. In light of this result, it seems likely that appropriate silanes can be designed in the future to accomplish faster hydride transfer for catalytic reactions.

Hydrogen Atom Transfer from Fe-H to Alkene.

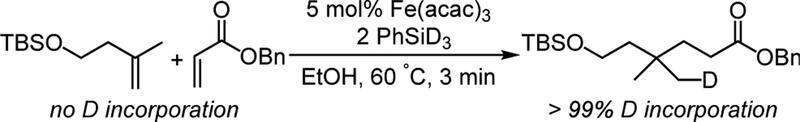

In the HAT alkene reactions, a key step is the transfer of a hydrogen atom from a metal-hydride complex to an alkene,1b and therefore we sought ways to experimentally probe this step for the intermolecular alkene cross-coupling. Thus, we studied the HAT alkene cross-coupling of TBS-protected 3-methylbut-3-en-1-ol with benzyl acrylate under the conditions of Lo et al., using FeIII(acac)3 as the precatalyst (Scheme 5).6a In this reaction, the metal-bound hydrogen in the putative hydride is derived from phenylsilane, and thus its fate can be probed by using PhSiD3 in place of PhSiH3. 1H NMR and 13C NMR analysis of the product (Figures S1-S2) show that the cross-coupled product has regiospecific D incorporation (Scheme 5), which agrees with previous work.6a In addition, it is important to consider whether the H-atom transfer is reversible, because M-H additions from isolated hydride species to alkenes were shown to be reversible by Halpern, Bullock, and Norton.19 Since the radical generated from the M-D compound would be singly deuterated, reversible HAT would lead to partially deuterated alkene starting material at low conversion. Therefore, a catalytic reaction run under normal conditions was stopped at 3 minutes (30% conversion), and analysis by NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (Figures S1-S5) showed that no D was incorporated into the remaining starting material. Therefore, the initial hydrogen atom addition to the alkene is irreversible, which agrees with our qualitative rationale for the normal isotope effect previously observed upon substitution of PhSiD3 for PhSiH3.6b

Scheme 5. Deuterium Transfer to Product Indicates that HAT is Not Reversible.

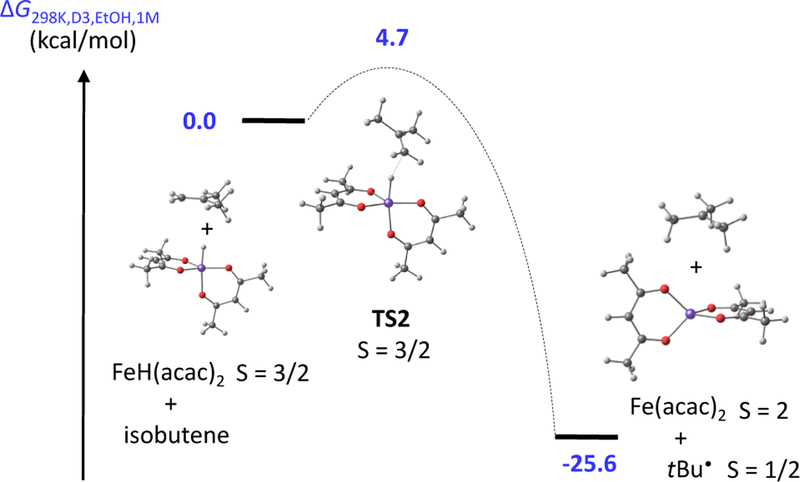

The pathway for HAT from the transient iron(III) hydride to the donor alkene was evaluated by DFT using isobutene as model H atom acceptor (Figure 3 and details in SI section 2.F). This reaction yields a tert-butyl radical and [FeII(acac)2], which was treated as the experimentally known quintet ground state. Hence, the reaction can take place on a single potential energy surface (PES), i.e. is spin-allowed, starting from either the intermediate-spin (S = 2 − 1/2 = 3/2) or high-spin (S = 2 + 1/2 = 5/2) hydride complex, whereas the HAT from the low-spin system would be spin-forbidden. The barrier for the spin-allowed reaction along the quartet surface is extremely low: we were able to optimize a transition state (TS2) that lies only 4.7 kcal/mol higher in free energy, making this step extremely rapid. (A rate constant of 2.2 × 109 s−1 M−1 can be calculated from the Eyring equation, though one should note that the geometry optimization uses the electronic energy, and therefore the saddle point on the free energy surface might be slightly different. In any case, this finding supports our conclusion above that HAT to the alkene is unlikely to be the turnover-limiting step as proposed earlier.6b) Hydrogen atom transfer from Fe to the alkene was calculated to be exergonic by 26 kcal/mol, which agrees with the experimental finding that HAT occurs irreversibly under the cross-coupling conditions.

Figure 3.

HAT pathway for ground-state [FeIIIH(acac)2] reaction with isobutene to give [FeII(acac)2] and tert-butyl radical.

The iron product from HAT, [FeII(acac)2], is known to form weak adducts with monodentate donor molecules, including EtOH.20 Indeed, trans-[FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2] has been isolated and crystallo-graphically characterized.6b We measured the variation of the chemical shift of the 1H NMR resonance for [FeII(acac)2] in benzene as a function of [EtOH], and the curve (Figure S20) yielded an association constant of 3.2 ± 0.2 M−1 at 80 °C, corresponding to ΔG° = −0.8 ± 0.1 kcal/mol. However, in this weak-binding regime, the stoichiometry is not evident from the binding curve. DFT calculations on the EtOH coordination process (SI section 2.G) gave a ΔG of + 1.3 kcal/mol for formation of [FeII(acac)2(EtOH)] and −0.6 kcal/mol for [FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2]. The excellent agreement validates the DFT calculations and explains why a single binding curve was observed (the second EtOH molecule binds more tightly than the first).

These energetics suggest that the speciation of [FeII(acac)2] in pure EtOH solvent (17 M) at 298 K is ca. 99% of 6-coordinate trans-[FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2] and 1% of 4-coordinate [FeII(acac)2], with only trace amounts of 5-coordinate [FeII(acac)2(EtOH)]. Hence, both the unsolvated [FeII(acac)2] and the alcohol complex trans-[FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2] are readily accessible reactive species for the ethanolic reactions to be explored in the remainder of this study.

Behavior of the Initial Alkyl Radical.

The product of HAT to the alkene is an alkyl radical. Though this alkyl radical may add to the acceptor alkene directly, our experience with OMRP and the previous suggestions of assistance by the persistent radical effect3 encouraged us to evaluate the possibility of its reversible binding to [FeII(acac)2], which would give an alkyliron(III) complex (eq 1).

| (1) |

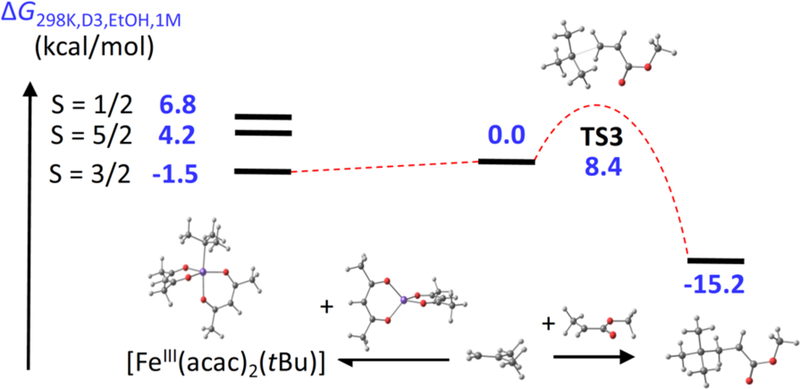

We calculate that the formation of the quartet state of the iron(III) tert-butyl complex is exergonic by 1.5 kcal/mol (Figure 4 and SI section 2.H), whereas the low- and high-spin states are found at higher energy. For this reason, the formation of the iron(III) alkyl complex can serve to decrease the concentration of the radical in solution. Thus, our computations indicate the potential for a weak persistent radical effect that “protects” the intermediate alkyl radical from bimolecular radical coupling.

Figure 4.

Reaction coordinates of two tert-butyl radical reactions: (left) trapping by [FeII(acac)2]; (right) addition to methyl acrylate.

The cross-selectivity of the alkene cross-coupling reaction arises because the nucleophilic alkyl radical (in the computations, modeled as a tert-butyl radical) reacts most rapidly with electron-poor alkenes. The relative rates for reaction of such radicals with alkenes are well-known in the literature.21 In this specific case, a radical is expected to react more than 103 times more rapidly with an acrylate ester than with a simple alkene.22 According to our calculations, the addition of tert-butyl radical to methyl acrylate has a barrier (TS3) of only 8.4 kcal/mol, and has a favorable ΔG = −15 kcal/mol (Figure 4 and SI section 2.I) as expected for the formation of a stabilized radical. Therefore, this C–C bond forming reaction is also expected to be irreversible. Because the acrylate radical is more stable, it is expected to form a weaker bond to the iron atom. This proposition was explored using the simpler propionate radical CH3CH• (COOMe) as a model for the produced radical. The formation of an Fe-C bond between this radical and iron(II) to give [FeIII(acac)2-(CHMeCOOMe)] in the preferred quartet state is calculated to be endergonic by 0.6 kcal/mol (SI section 2.J). The O-bound isomer was calculated to be 4 kcal/mol higher in energy than the C-bound isomer. Therefore, the acrylate radical should not benefit from the persistent radical effect at catalytic concentrations of iron. Additional calculations of the Fe-C bond strength in [FeIII(acac)2(CHMeCOOMe)] were also conducted with other functionals to validate our computational method (see SI section K).

Trapping of the Acrylate Radical through the Previously Proposed Stepwise ET/PT Mechanism.

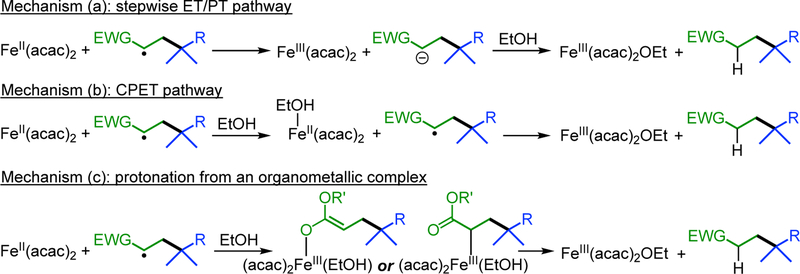

The acrylate radical, which derives from the attack of the initial alkyl radical on the acceptor alkene, is a key species in the catalytic cycle. Its conversion into the product requires one proton and one electron. The regioselectivity of deuterium transfer from EtOD to the product6a indicates that the proton derives from ethanol. In the previously proposed mechanism for the cross-coupling reactions, the trapping takes place through a two-step mechanism: initial electron transfer from the iron(II) species to the acrylate radical to yield an acrylate anion, which accepts proton transfer from ethanol to generate the product and the iron(III) ethoxide (this stepwise mechanism “ET/PT” is shown as (a) in Scheme 6). We tested this idea using both computations and experiments.

Scheme 6. Mechanisms for Quenching the Product Radical.

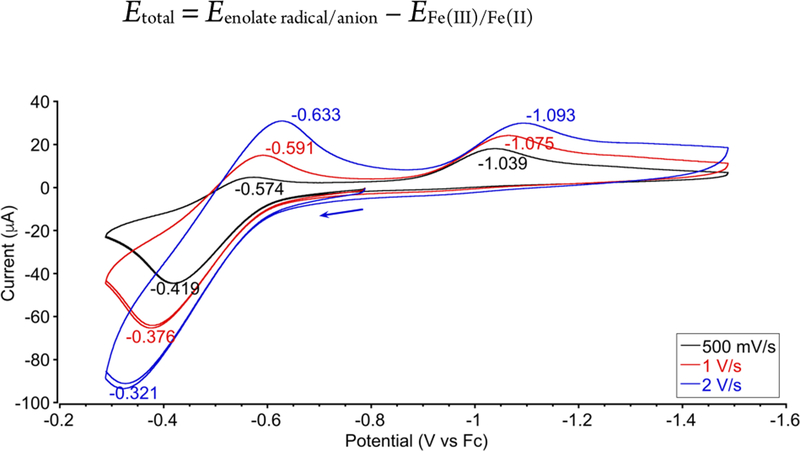

Since mechanism (a) is initiated by electron transfer (ET) from iron(II) to the acrylate radical, we tested its feasibility by determining the thermodynamics of ET from iron(II) to the acrylate radical. Cyclic voltammetry of [FeII(acac)2] in ethanol (the solvent used in the catalytic reaction) showed an irreversible oxidation wave at moderate scan rates (≤ 500 mV/s), with the cathodic peak current much smaller than the anodic peak current (Figure 5, black trace). We attribute the irreversibility to the limited stability of [FeIII(acac)2]+ in solution. The instability of related iron-acetylacetonate species has been reported previously23 and we have observed that oxidation of [FeII(acac)2] in air gives [FeIII(acac)3]6b with ligand redistribution.20c Fortunately, increasing the scan rate to 2 V/s improved chemical reversibility (ipc ~ ipa), enabling the calculation of a half-wave potential (E1/2) of −0.48 V vs. Fc+/0 (Figure 5, blue trace). DFT calculations (SI, section 2.L) predicted this potential to be −0.42 V, which supports this value (and provides another successful validation of the computational protocol).

| (2) |

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammetry of [FeII(acac)2] (3 mM) in EtOH with NBu4BF4 (0.1 M) as supporting electrolyte, showing the FeIII/II redox couple at −0.48 V. The greater reversibility at faster scan rate suggests that the iron(III) species is unstable.

Judging the thermodynamics of ET requires one to compare this value to the potential for the acrylate radical/anion couple. The redox potential of CH(CH3)CO2CH3•/−, a close relative of the product radical, has been measured to be −1.04 V vs. Fc+/0 in acetonitrile.24 With the caveat that this literature value is in a different solvent, this analysis suggests that ET from iron(II) to the radical is unfavorable, with E of roughly −0.56 V (uphill by 13 kcal/mol). Our DFT calculations predict that it is even more uphill (35.0 kcal/mol) in ethanol (SI section 2.L). Thus ET would be expected to introduce a substantial barrier to the ET/PT two-step mechanism that potentially keeps it from being kinetically competent.

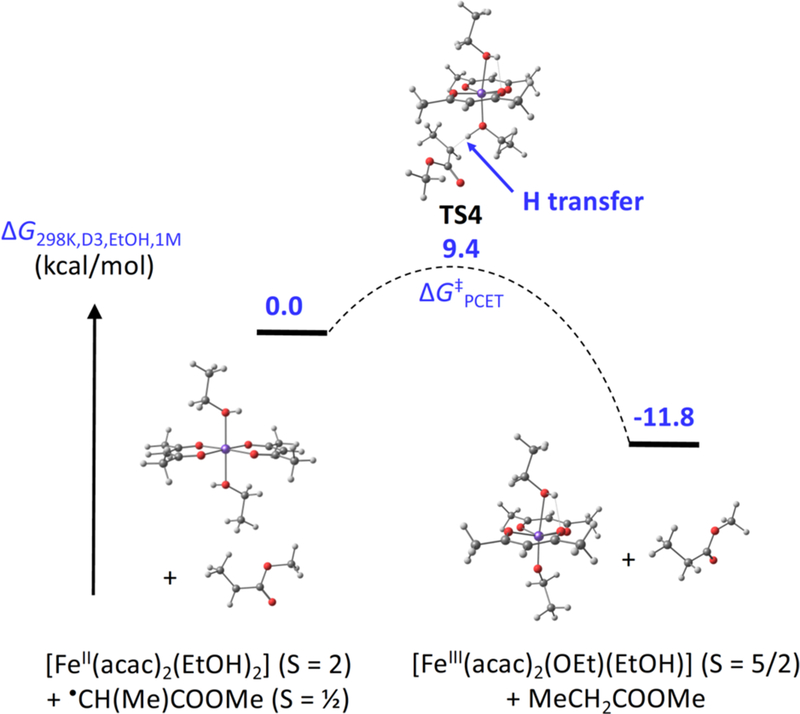

Concerted Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer.

In mechanism (b), we consider the hypothesis that there could be inner-sphere electron transfer from iron to the radical during proton transfer from ethanol. This process has been termed concerted proton-electron transfer (CPET), which is a subset of PCET reactions that are concerted.25 In these concerted PCET reactions, the proton and the electron are transferred in a single elementary step, with a barrier that is lower than that for either proton transfer or electron transfer.26 This situation is termed multisite concerted PCET,25b because the proton and electron come from different locations. We examined this concerted PCET process in a truncated substrate using DFT calculations (Figure 6 and SI section 2.M). Approach of the model propionate radical CH3CH• (COOMe) to the iron(II) compound trans-[FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2] gave transfer of the proton and electron to yield acrylate and the iron(III) compound trans-[FeIII(acac)2(OEt)(EtOH)], through a transition state TS4 lying only ΔGPCET‡ = 9.4 kcal/mol above the energy of the starting materials. This low barrier corresponds to a very rapid rate at room temperature, and importantly is lower than the barrier for the ET/PT mechanism above. In the concerted PCET transition state (TS3), the O-H distance is 1.14 Å, much longer than 0.97 Å in the starting material, and the incipient C---H bond distance is 1.456 Å. The long distances, as well as the low spin density (−0.021 vs. 0.000 in the starting complex) and Mulliken charge (+0.38 e−, identical to that in the starting FeII complex) on the transferring proton are characteristic of a synchronous proton-electron transfer.27

Figure 6.

Reaction coordinate for concerted PCET from [FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2] to CH3CH•(COOMe).

In addition to the productive concerted PCET described above, we also used DFT to evaluate concerted PCET from [Fe(acac)2(EtOH)2] to the tert-butyl radical, which models a side reaction that would give the net hydrogenation of the donor alkene without C-C bond formation. The calculated transition state energy is 7.3 kcal/mol, which is slightly lower than that for the productive concerted PCET (9.4 kcal/mol), but the rate law for the side reaction is kPCET,tBu[tBu•][(acac)2FeII(EtOH)2] while the rate law for the C–C coupling is kcc[tBu•] [alkene]. Since the concentration of the trapping alkene is much higher than the Fe concentration, the rate of the reaction with the alkene would be similar despite the lower rate constant. Using the Eyring equation, we calculate a rate constant for the CPET side reaction of 3 × 107 M−1s−1 at 298 K for a rate law kCPET,tBu[tBu•][(acac)2FeII(EtOH)2]. The rate constant for the C-C bond formation, on the other hand, would be 4 × 106 M−1s−1 for a rate law kcc[tBu•] [alkene]. Importantly, this model predicts that the C-C coupling of tert-butyl radical to acceptor alkene should become less favorable as the reaction progresses due to the decrease in the relative concentration of trapping alkene. Monitoring the product distribution in the standard coupling reaction at 60 °C indicates that, indeed, the reduction of donor alkene is a competing side reaction and occurs only later in the reaction as the acceptor olefin is consumed (Figure S21). This explains why the reaction yield for cross-coupling is often enhanced by using superstoichiometric amounts of the acceptor alkene,6b because then the concentration of acceptor alkene does not drop precipitously in the later part of the reaction.

A second question concerns why the acrylate product radical undergoes concerted PCET rather than continuing to add to further acrylate substrate. In this case, we must compare kPCET,R [R•][FeII] and kp[R•] [alkene], where R• is the acrylate radical and kp is the propagation rate constant of the acrylate monomer polymerization. The calculations for the CH3CH•(COOMe) model predict ΔG‡PCET,R of 9.4 kcal/mol (see above), while the calculation of the model product radical addition to methyl acrylate predicts a barrier ΔG‡p = 10.9 kcal/mol (SI, section 2.N). Due to the skewed relative concentrations, the calculated rates are again close, and in agreement Lo et al. observed side products from multiple additions of acceptor alkene.6b Clearly, there is a delicate balance between the concerted PCET and alkene addition rates, and the success of the catalytic cross-coupling rests on the tuning of these two processes for the two different radicals.

Kinetic Isotope Effects.

If PCET to the acrylate radical (either concerted or stepwise with slow PT) were turnover-limiting, then there would be a kinetic isotope effect between reactions in EtOH versus EtOD. The kinetic isotope effect for the overall catalysis was measured by comparing separate standard catalytic reactions in EtOH and EtOD (Scheme 6, top). The initial rates at 40 °C were 6.5 ± 0.7 × 10−5 M/s and 6.2 ± 1.2 × 10−5 M/s, respectively, and thus there is no kinetic isotope effect. This suggests that PCET is not the turnover-limiting step in the cycle. We also used a competition experiment in order to isolate the KIE of the step involving transfer of the H from ethanol (which we call the product isotope effect “PIE”). Performing the catalytic reaction in a 1:1 mixture of EtOH and EtOD (Scheme 6, bottom) gave a product with 21 ± 1% D incorporation, which indicates a PIE of 3.8 ± 0.1. The difference in the KIE and PIE values28 indicates that the PCET step is not turnover-limiting, but rather lies after the turnover-limiting step. This is consistent with a low-energy transition state for transfer of H to the propionate radical.

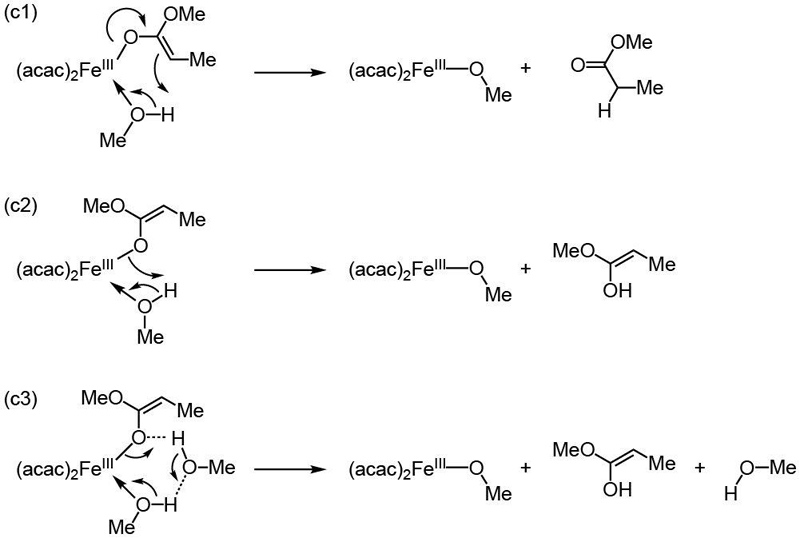

Protonation of Iron-Bound Intermediates.

In addition, we considered mechanism (c), in which the product radical forms a bond to iron(II) to give an intermediate that is susceptible to protonation. As noted above, a putative alkyliron(III) intermediate lies at higher energy than the free radical + iron(II), but it could be a kinetically competent intermediate if the subsequent protonation occurs with a low barrier. For the sake of computational efficiency, in addition of keeping propionate as a model alkyl, MeOH was used as model alcohol in these calculations (SI section 2.O). Relaxed PES scans, for both quartet and sextet spin states and considering up to two MeOH molecules, identified reasonable pathways leading from this alkyl complex to products. Protonation of the C-bound enolate (SI section 2.P) required a transition state with an electronic energy more than 20 kcal/mol higher than CH3CH•(COOMe), MeOH, and [FeII(acac)2], or led to Fe-C homolysis and subsequent concerted PCET through a transition state indistinguishable from that in mechanism (b). Therefore, we rule out this mechanistic possibility.

In contrast, the higher-energy O-bound enolate (SI section 2.Q) revealed feasible pathways (Scheme 7). A first possibility consists of the direct proton transfer to the enolate C atom, generating the product as shown as (c1). This was calculated to be difficult, with the optimized TS lying at nearly 20 kcal/mol above [FeII(acac)2], MeOH and CH3CH•(COOMe). The high activation barrier is attributed to the unfavorable hybridization change of the C atom from sp2 to sp3, with loss of the enolate π delocalization. Direct proton transfer to the enolate O atom, leading to the ester enol tautomer of the desired product, is expected to be unfavorable because it requires a strained 4-membered ring, as shown in (c2) in Scheme 7.

Scheme 7. Variants of Mechanism (c), Intramolecular Proton Transfer to O-bound Ester Enolate.

However, the computed activation barriers drop dramatically by including an additional methanol (mechanism (c3) in Scheme 7) as a “proton shuttle” as shown for other systems.29 Despite the assistance from additional alcohol molecules, the product of protonation lies 11.0 kcal/mol above [FeII(acac)2], MeOH and CH3CH•(COOMe). The pathway would then be completed by the exergonic ester enol tautomerization. So, the protonation pathway requires an intermediate that is slightly higher in energy than the PCET barrier (see SI, section 2.Q), but it is close enough for consideration.

Experimentally Testing Concerted vs. Stepwise PCET to a Model Alkyl Radical.

In order to experimentally test the conditions under which the putative active species can achieve multisite concerted PCET or stepwise PCET to an alkyl radical, we used azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN) as a source of the isobutyryl radical. Transfer of a proton and an electron would lead to isobutyronitrile (Me2C(CN)-H), by forming a new C-H bond of 92 kcal/mol.30 In control experiments without [FeII(acac)2], heating AIBN with 20 equiv of EtOH at 80 °C in acetonitrile yields undetectable amount of Me2C(CN)-H by 1H NMR spectroscopy, and the main product is the radical homocoupling product (Me2C(CN)–C(CN)Me2) (Figure S15). In contrast, the same reaction with 2 equiv of [FeII(acac)2] per AIBN (one per radical) gave an 86 ± 3% yield of Me2C(CN)-H. and substituting ethanol-OD and ethanol-d6 result in Me2C(CN)-D with 88 ± 2% and 89 ± 2% deuterium incorporation (quantified by 1H NMR, figure S12-S14). Thus, the combination of Fe(acac)2 and EtOH indeed generates a competent system for PCET.

In order to distinguish whether it is a coordinated acid that performs PCET, we repeated these experiments with Et3NH+BF4−, where the acid cannot coordinate to Fe. Importantly, the triethylammonium cation is a stronger acid than ethanol (Ka is more than 1010 higher).31 Addition of Et3NH+BF4− to a heated acetonitrile solution as a control experiment gives only 1% of Me2C(CN)-H (Figure S22). Repeating this experiment with 1 equiv and 20 equiv of Fe(acac)2 gave 25 ± 2% and 54 ± 5% yield of Me2C(CN)-H respectively. These yields are lower than the ones observed with ethanol, indicating that there is a pathway in ethanol that requires coordination: we attribute this to concerted PCET from [Fe(acac)2(EtOH)2]. However, PCET is still observed when using the Et3NH+ salt, which indicates that there is a second pathway: we attribute this to a stepwise PCET pathway. In the present case, this second pathway cannot correspond to one of the mechanism (c) variants, because the proton donor cannot coordinate the metal center. However, there may be an intermolecular variant consisting of proton transfer from outer sphere Et3NH+ to the C-bound or N-bound FeIII cyanoisopropyl complex.

DISCUSSION

Hydride Species in HAT Alkene Reactions.

A number of stoichiometric hydrogenation and cyclization reactions are mediated by isolable transition-metal hydride species. The seminal observation of chemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization (CIDNP) and an inverse kinetic isotope effect from the reduction of styrene with HMn(CO)5 established hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from a metal hydride to an alkene, and indicated that HAT is reversible.19a Further observation of inverse isotope effects from 2-cyclopropylpropene reacting with HCr(CO)3Cp, and the observation of CIDNP from HFe(CO)2Cp in diene hydrogenation, demonstrated reversible hydrogen atom transfer from first-row transition metal hydrides to alkenes.19b, 32 Two characteristics of these literature reactions of isolable hydride complexes have been (1) the HAT was reversible, and (2) the HAT was the rate-limiting step. This is presumably related to the fact that these reactions use stable hydride complexes with relatively high metal-hydrogen bond energies. For example, the M-H BDE values of HCr(CO)3Cp, HMn(CO)5, cis-HMn(CO)4PPh3 and HFe(CO)2Cp have been reported to be 62, 68, 69, and 68 kcal/mol, respectively.19b, 33

Our studies indicate that the unobserved iron(III) hydride species that are involved in room-temperature catalytic alkene coupling have amazingly weak M-H bonds that are quite different than the previously studied systems. The DFT calculated gas-phase bond dissociation enthalpy of (acac)2FeIII-H at 298 K from the quartet ground state is only 17.3 kcal/mol (SI section 2.R). As a result of this very weak M–H bond, hydrogen atom addition from the hydride complex to the alkene is irreversible, which contrasts with the reversible hydrogen atom additions in the above systems with M-H bond energies greater than 60 kcal/mol.19a–c This difference in reversibility was previously proposed on the basis of kinetic isotope effect studies,6b and is supported here by isotopic labeling experiments that rule out reversibility, and by computational studies that show the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT in Scheme 8) to be thermodynamically favorable by more than 25 kcal/mol in free energy. The barrier for this exergonic HAT is much lower than the barriers for the previously studied reversible systems with isolable hydrides, as expected from the Hammond principle. This low barrier explains the rapid rate of the iron-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction despite the undetectably low concentration of the transient hydride species during catalysis.

Scheme 8. Mechanism for Iron-Catalyzed Intermolecular Cross-Coupling of Alkenes, Supported by Experiments and Computations.

The observation that the choice of silane and iron alkoxide drastically influence the catalytic reaction rate, combined with the agreement between calculated and observed barries of 22–24 kcal/mol, indicate that the turnover determining transition state (TDTS in Scheme 8) is the generation of the key acac-supported iron(III) hydride complex. Its steady-state concentration would be too small for spectroscopic detection (see calculation in SI, section 2.S). Because the transient Fe-H species has not been possible to observe, we used DFT to computationally define the most likely geometry, energy, and reactivity. The computations indicate that the hydride monomer is lower in energy than multimetallic hydrides, and is highly reactive. As noted by a reviewer, a sufficiently reactive polynuclear hydride is a conceivable intermediate, but hydride dimers typically have lower reactivity than monomers,34 and it is unclear why the aggregate would react even more rapidly than the monomer. Interestingly, all three possible spin states of the mononuclear hydride complex have very similar energies and geometries, which suggests that crossover from one state to the other may be facile. We have suggested that electronic flexibility of this type may facilitate catalytic reactions, by providing multiple opportunities for low barriers.35

The low barrier for this hydride addition conflicts with our earlier conclusion that this is the turnover-limiting step in the catalytic cycle.6b Other data also conflict with this idea: here we show that the overall catalytic reaction rate depends on the choice of silane and the presence of ethoxide, implicating the transfer of hydride from the silane to iron as the turnover-limiting step. This concords with the high-energy hydride species, and is supported by calculations which indicate that the exchange of hydride and ethoxide has a relatively high activation barrier.

Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer (PCET) from an Iron(II)-Ethanol Complex.

There are a variety of different HAT alkene reactions, but despite the different products, all involve HAT from a metal hydride that should result in formation of a metal center in which the formal oxidation state is reduced by one.1b In order to reoxidize the metal, it is natural that chemists have postulated electron transfer from the reduced metal to the radical.1b However, alkyl radicals are weak oxidizing agents.36 Therefore, we explored the feasibility of several potential pathways.

Earlier work on the HAT alkene cross-coupling reaction proposed that electron transfer (ET) is followed by a separate proton transfer (PT) step. However, in the FeIII/II case studied here, the iron(II) species has too little reducing power to accomplish the proposed ET step. Of course, the ET step does not need to be favorable to be part of the catalytic cycle: if the barrier is small, then an uphill reaction can be followed by a more exergonic step that consumes the high-energy intermediate. However, the reorganization energy of the ester radical to anion was determined to be 26 kcal/mol,24 which would add a substantial kinetic barrier to the unfavorable thermodynamics of the proposed electron transfer reaction. The experimentally determined overall barrier from our experiments on the catalytic reaction described in Scheme 5 at 40°C is 22.8 ± 0.2 kcal/mol. These results suggest that the proposed ET step in the ET/PT mechanism (mechanism a) may not be kinetically competent, and that other mechanisms should be considered, in which ET and PT are concerted or involve binding of substrates.37

Here, we use “PCET” as a general term for movement of proton and electron between reagents, “HAT” to indicate movement of proton and electron from the same site (e.g. transfer from the iron(III)-hydride to the acceptor alkene), and “concerted PCET” to indicate the concerted transfer of proton and electron from different sites (e.g. transfer of the electron from iron(II) and the proton from coordinated alcohol in the quenching of the product radical).25b PCET has long been discussed in reactions that oxidize organic compounds, particularly in bioinorganic chemistry,26, 38 but the involvement of concerted PCET in organic reduction reactions has been studied more recently.39 Initial attention in the synthetic community came from the realization that coordination to a metal can lower the BDFE of the O-H bond, enabling the use of abundant H•·sources like water and alcohols in place of traditional H• sources like tin hydrides. Cardenas, Cuerva, Flowers, and Mayer have shown that H2O complexes of titanium(III) and samarium(II) are particularly effective H• donors due to their strong reducing ability and formation of strong M-O bonds, and computations indicate that the proton and electron transfer to the radical are concerted.40 Chirik and others have expanded this concept to include N-H bonds as reductants.41 However, we are not aware of previous studies where concerted PCET from metal-alcohol complexes has been linked to catalytic HAT alkene cross-coupling reactions.

In the HAT alkene cross-coupling reactions studied here, the incorporation of deuterium from EtOD shows that the alcoholic OH proton is the source of the new C-H bond (92 kcal/mol42 or 90 kcal/mol for the model H-CH(Me)(COOMe) system according to our DFT calculations (SI section 2.P2). This new bond is much weaker than the O-H bond in ethanol (104 kcal/mol).6a, 6b However, our computations indicate that coordination of the ethanol to FeII(acac)2 lowers the O-H bond dissociation free energy from 104 kcal/mol to 74 kcal/mol (see SI section 2.P3). We experimentally confirmed the PCET ability of the iron(II) ethanol complex by showing that it reacts with the isobutyronitrilyl radical formed by AIBN, forming a C-H bond that is 92 kcal/mol.30 Therefore, the predominance of iron(II) during the catalytic HAT alkene cross-coupling reaction binds EtOH, enabling the alcohol to become a competent PCET reductant. We calculate a low-lying transition state for a synchronous multisite PCET. The normal kinetic isotope effect of 3.8 for this step (from competition experiments that target this step of the mechanism) is consistent with concerted PCET.

Mayer has noted that two-step PT/ET or ET/PT sequences tend to occur when there are similar acidities for the two sites or similar redox potentials for the two sites, respectively.25b Here, the coordinated ethanol is expected to be much more acidic than the ester product, and the FeIII/II potential is substantially more positive than that of the ester-based radical/anion couple, consistent with the preference for concerted PCET. Similar considerations have been considered by Cárdenas and Cuerva for TiIII-water complexes, leading to the conclusion that proton and electron transfers are concerted.40a, 40c We speculate that other HAT alkene reactions catalyzed by different metals may similarly use concerted PCET as a “shortcut” that avoids unfavorable ET in a range of HAT alkene reactions. For example, formal hydroamination by nitro compounds,4k, 43 hydrohydrazidation of alkenes,3c coupling of diazoalkanes to alkenes,44 and radical cyclization of alkenes and ketones45 all involve postulated ET/PT sequences that might be concerted instead, and thus these mechanisms deserve study in this context. Howeer, related HAT additions to quinone methides would give a radical that is much easier to reduce, and therefore a stepwise ET/PT mechanism could be more likely.46

Consideration of Fe(III) Alkyl and Enolate Intermediates.

The formation of bonds between metals and radicals is well-established in related OMRP reactions. For example, the 4-coordinate diaminebis(phenolate)iron(II) system, which is isoelectronic with Fe(acac)2, reversibly traps polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate) chains and controls polymer growth by an OMRP mechanism.47 In the case studied here, there is weak binding of the initial alkyl radical to iron(II), which lowers its concentration and prevents extensive homocoupling. However, the acrylate radical (formed after reaction with the alkene) is more stable, and forms an accordingly weaker bond to iron(II). Our calculations indicate that the BDFE of the iron(III)-acrylate radical adduct is negative, and therefore this radical is not protected through the PRE and could be preferentially quenched through concerted PCET from [FeII(acac)2(EtOH)2]. Thus the metal-carbon bond strength in the transient organometallic complex potentially represents another control strategy for HAT alkene reactions.

Though the iron(III) complex that comes from iron(II) and the acrylate product radical has a very low concentration, it is susceptible to protonation by the alcohol present, but only as the O-bound enolate. This iron(III) adduct with the radical proceeds to product with very low barriers using a proton-shuttle pathway, though it has a relatively high barrier mandated by the high energy of the enol tautomer of this ester. Our experimental comparison of coordinating (EtOH) and non-coordinating (Et3NH+) acids is most consistent with the idea that both the protonation of the enolate and the concerted PCET can occur, and this is compatible with the similar calculated barriers for these two pathways.

Our results also help to analyze the selectivity of the catalytic reaction and how it avoids undesired pathways. For example, the product acrylate radical could add to a second acceptor alkene to give polymerized products. The two likely pathways to quench the product radical presented in this work (concerted PCET and intermolecular protonolysis of O-bound enolate complex) are in competition with the polymerization process. Therefore, understanding the factors governing the rate of the product radical quenching step will be a key to outcompete the desired side reaction in the iron-catalyzed alkene cross-coupling reaction. Future studies will explore a range of alcohols that could provide higher selectivity and yield.

CONCLUSIONS

Though HAT alkene reactions are typically viewed as free radical reactions in which the metal’s main role is radical generation, our experimental and computational studies on the iron-catalyzed alkene cross-coupling demonstrate the intimate involvement of iron species throughout the catalytic cycle. These function not only to donate H• from an iron-hydride complex, but also form Fe-C bonds that decrease the concentration of free radicals, as well as Fe-O bonds that make alcohols into good H• donors.

Our results show many of the characteristics of the metal center that are required during catalysis, which should be useful for rational design of catalysts. One is the high reactivity of the metal-hydride species, which gives rapid and irreversible donation of a hydrogen atom to the donor alkene. The use of weak-field ligands in the acac-iron system gives a very weak FeIII–H bond that transfers H•·rapidly to the alkene, and the lack of reversibility prevents chain transfer or β-hydride elimination. Second, our calculations and experiments have showed that there are concurrent multiple low-energy pathways for quenching the radical with alcohol and iron(II). The large normal PIE is consistent with concerted PCET from an iron(II)-alcohol complex, and is also consistent with iron binding of the radical to iron(II) to form an O-bound enolate-iron(III) complex that has formally transferred an electron to the radical. In the latter case, subsequent irreversible protonation yields the product.

We show that the iron(III) hydride is important, but after it loses H•, the iron(II) product is also influential. It is be a reducing agent, but not in the traditional sense. It gives an alcohol complex that is an excellent H· donor through PCET. Alternatively, it can bind radicals to form a variety of species including an iron(III)-enolate complex which can be protonated to release the product. The alcohol, which was previously viewed as merely the proton source for the intermediate enolate, is now also implicated as a central player in key mechanistic steps.

We highlight the new insights into the mechanism above in Scheme 8, which we propose as a more accurate picture of the mechanism for alkene cross-coupling by Fe-acac catalysts. These insights into the energetics of various mechanistic steps may be applicable to various HAT alkene coupling reactions such as hydropyridylation, hydroamination, hydroazidation, hydrohydrazination, hydrocyanation, hydration, and hydrogenation that were recently reviewed,1b and therefore provide motivation and methods for mechanistic work on other HAT alkene reactions.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

A series of experimental and computational studies demonstrate influential details of iron-based steps during catalytic radical cross-coupling reactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PLH thanks the National Science Foundation (CHE-1465017), National Institutes of Health (GM129081) and the Humboldt Foundation for support. We thank Prof. James Mayer, Dr. Kazimer Skubi, Dr. Julian Lo, and Prof. Phil Baran for helpful discussions. RP thanks the CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) for support. This work used the HPC resources of IDRIS under the allocation 2016–086343 made by GENCI (Grand Équipement National de Calcul Intensif) and the resources of the CICT (Centre Interuniversitaire de Calcul de Toulouse, project CALMIP).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental, spectroscopic, and computational details (PDF) Crystallographic Information File for [Fe(acac)2(μ-OEt)]2 (CIF)

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Olah GA; Prakash GKS, Carbocation Chemistry Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2004; [Google Scholar]; (b) Crossley SWM; Obradors C; Martinez RM; Shenvi RA, Mn-, Fe-, and Co-Catalyzed Radical Hydrofunctionalizations of Olefins. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 8912–9000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leggans EK; Barker TJ; Duncan KK; Boger DL, Iron(III)/NaBH4-Mediated Additions to Unactivated Alkenes: Synthesis of Novel 20′-Vinblastine Analogues. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 1428–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Yan M; Lo JC; Edwards JT; Baran PS, Radicals: Reactive Intermediates with Translational Potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12692–12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Recent evidence for reversible radical formation: Shevick SL; Obradors C; Shenvi RA Mechanistic Interrogation of Co/Ni-Dual Catalyzed Hydroarylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12056–12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Waser J; Carreira EM, Convenient Synthesis of Alkylhydrazides by the Cobalt-Catalyzed Hydrohydrazination Reaction of Olefins and Azodicarboxylates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 5676–5677; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Waser J; Carreira EM, Catalytic Hydrohydrazination of a Wide Range of Alkenes with a Simple Mn Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 4099–4102; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Waser J; Gaspar B; Nambu H; Carreira EM, Hydrazines and Azides via the Metal-Catalyzed Hydrohydrazination and Hydroazidation of Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 11693–11712; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gaspar B; Carreira EM, Mild Cobalt-Catalyzed Hydrocyanation of Olefins with Tosyl Cyanide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46, 4519–4522; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gaspar B; Carreira EM, Catalytic Hydrochlorination of Unactivated Olefins with para-Toluenesulfonyl Chloride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 5758–5760; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gaspar B; Carreira EM, Cobalt Catalyzed Functionalization of Unactivated Alkenes: Regioselective Reductive C–C Bond Forming Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 13214–13215; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Barker TJ; Boger DL, Fe(III)/NaBH4-Mediated Free Radical Hydrofluorination of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 13588–13591; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) King SM; Ma X; Herzon SB, A Method for the Selective Hydrogenation of Alkenyl Halides to Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 6884–6887; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Crossley SWM; Barabé F; Shenvi RA, Simple, Chemoselective, Catalytic Olefin Isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 16788–16791; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Iwasaki K; Wan KK; Oppedisano A; Crossley SWM; Shenvi RA, Simple, Chemoselective Hydrogenation with Thermodynamic Stereocontrol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 1300–1303; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Gui J; Pan C-M; Jin Y; Qin T; Lo JC; Lee BJ; Spergel SH; Mertzman ME; Pitts WJ; La Cruz TE; Schmidt MA; Darvatkar N; Natarajan SR; Baran PS, Practical olefin hydroamination with nitroarenes. Science 2015, 348, 886–891; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Dao HT; Li C; Michaudel Q; Maxwell BD; Baran PS, Hydromethylation of Unactivated Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 8046–8049; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Ma X; Herzon SB, Intermolecular Hydropyridylation of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 8718–8721; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Green SA; Matos JLM; Yagi A; Shenvi RA, Branch-Selective Hydroarylation: Iodoarene–Olefin Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12779–12782; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Ma X; Dang H; Rose JA; Rablen P; Herzon SB, Hydroheteroarylation of Unactivated Alkenes Using N-Methoxyheteroarenium Salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 5998–6007; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Desage-El Murr M; Fensterbank L; Ollivier C, Iron and Single Electron Transfer: All is in the Ligand. Isr. J. Chem 2017, 57, 1160–1169; [Google Scholar]; (q) Inoki S; Kato K; Isayama S; Mukaiyama T, A New and Facile Method for the Direct Preparation of α-Hydroxycarboxylic Acid Esters from α,β-Unsaturated Carboxylic Acid Esters with Molecular Oxygen and Phenylsilane Catalyzed by Bis(dipivaloylmethanato)manganese(II) Complex. Chem. Lett 1990, 19, 1869–1872; [Google Scholar]; (r) Magnus P; Payne AH; Waring MJ; Scott DA; Lynch V, Conversion of α,β-unsaturated ketones into α-hydroxy ketones using an MnIII catalyst, phenylsilane and dioxygen: acceleration of conjugate hydride reduction by dioxygen. Tetrahedron Lett 2000, 41, 9725–9730. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo JC; Yabe Y; Baran PS, A Practical and Catalytic Reductive Olefin Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 1304–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Lo JC; Gui J; Yabe Y; Pan C-M; Baran PS, Functionalized olefin cross-coupling to construct carbon–carbon bonds. Nature 2014, 516, 343–348; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lo JC; Kim D; Pan C-M; Edwards JT; Yabe Y; Gui J; Qin T; Gutiérrez S; Giacoboni J; Smith MW; Holland PL; Baran PS, Fe-Catalyzed C–C Bond Construction from Olefins via Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2484–2503; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shen Q; Hartwig JF, [(CyPF-tBu)PdCl2]: An Air-Stable, One-Component, Highly Efficient Catalyst for Amination of Heteroaryl and Aryl Halides. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 4109–4112; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) George DT; Kuenstner EJ; Pronin SV, Synthesis of Emindole SB. Synlett 2017, 28, 12–18; [Google Scholar]; (e) Qi J; Zheng J; Cui S, Fe(III)-Catalyzed Hydroallylation of Unactivated Alkenes with Morita–Baylis–Hillman Adducts. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 1355–1358; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Amatov T; Pohl R; Cisařová I; Jahn U, Sequential Oxidative and Reductive Radical Cyclization Approach toward Asperparaline C and Synthesis of Its 8-Oxo Analogue. Org. Lett 2017, 19, 1152–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMillen DF; Golden DM, Hydrocarbon Bond Dissociation Energies. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem 1982, 33, 493–532. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokuyasu T; Kunikawa S; Masuyama A; Nojima M, Co(III)–Alkyl Complex- and Co(III)–Alkylperoxo Complex-Catalyzed Triethylsilyl-peroxidation of Alkenes with Molecular Oxygen and Triethylsilane. Org. Lett 2002, 4, 3595–3598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Münck E, Aspects of Iron-57 Mossbauer Spectroscopy. In Physical Methods in Bioinorganic Chemistry, Que L, Ed. University Science Books: New York, 2000; pp 287–319. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Bachmann WE; Wiselogle FY, The Reversible Dissociation of Pentaarylethanes. J. Org. Chem 1936, 1, 354–382; [Google Scholar]; (b) Fischer H, The Persistent Radical Effect: A Principle for Selective Radical Reactions and Living Radical Polymerizations. Chem. Rev 2001, 101, 3581–3610; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Studer A, The Persistent Radical Effect in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Eur. J 2001, 7, 1159–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daikh BE; Finke RG, The persistent radical effect: a prototype example of extreme, 105 to 1, product selectivity in a free-radical reaction involving persistent CoII[macrocycle] and alkyl free radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 2938–2943. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Poli R, Relationship between one-electron transition metal reactivity and radical polymerization processes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 5058–5070; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith KM; McNeil WS; Abd-El-Aziz AS, Organometallic-Mediated Radical Polymerization: Developing Well-Defined Complexes for Reversible Transition Metal-Alkyl Bond Homolysis. Macromol. Chem. Phys 2010, 211, 10–16; [Google Scholar]; (c) Hurtgen M; Detrembleur C; Jerome C; Debuigne A , Insight into Organometallic-Mediated Radical Polymerization. Polym. Rev 2011, 51, 188–213; [Google Scholar]; (d) Poli R, Radical Coordination Chemistry and Its Relevance to Metal-Mediated Radical Polymerization. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2011, 1513–1530; [Google Scholar]; (e) Allan LEN; Perry MR; Shaver MP, Organometallic mediated radical polymerization. Prog. Polym. Sci 2012, 37, 127–156; [Google Scholar]; (f) Poli R, Organometallic Mediated Radical Polymerization. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obradors C; Martinez RM; Shenvi RA, Ph(i-PrO)SiH2: An Exceptional Reductant for Metal-Catalyzed Hydrogen Atom Transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 4962–4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.We showed earlier6b that PhSiH3/PhSiD3 gives a kinetic isotope effect of 1.5, which is too small to have a major influence on the outcome of this labeling experiment.

- 15.(a) Salomon O; Reiher M; Hess BA, Assertion and validation of the performance of the B3LYP* functional for the first transition metal row and the G2 test set. J. Chem. Phys 2002, 117, 4729–4737; [Google Scholar]; (b) Harvey J; Aschi M, Modelling spin-forbidden reactions: recombination of carbon monoxide with iron tetracarbonyl. Faraday Disc 2003, 124, 129–143; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Harvey JN; Poli R , Computational study of the spin-forbidden H2 oxidative addition to 16-electron Fe(0) Complexes. Dalton Trans 2003, 4100–4106; [Google Scholar]; (d) Carreón-Macedo J-L; Harvey JN, Do spin state changes matter in organometallic chemistry? A computational study. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 5789–5797; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Besora M; Carreon-Macedo JL; Cowan AJ; George MW; Harvey JN; Portius P; Ronayne KL; Sun XZ; Towrie M, A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study on the Role of Spin States in the Chemistry of Fe(CO)5 Photoproducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3583–3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu C-HS; Rossman GR; Gray HB; Hammond GS; Schugar HJ, Chelates of β-diketones. VI. Synthesis and characterization of dimeric dialkoxo-bridged iron(III) complexes with acetylacetone and 2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dione (HDPM). Inorg. Chem 1972, 11, 990–994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Dugan TR; Bill E; MacLeod KC; Brennessel WW; Holland PL, Synthesis, Spectroscopy, and Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange in High-Spin Iron(II) Hydride Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 2370–2380; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gieshoff TN; Chakraborty U; Villa M; Jacobi von Wangelin A, Alkene Hydrogenations by Soluble Iron Nanocluster Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 3585–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The same trend has been observed for borohydrides; addition of OR substituents renders them more powerful hydride donors (Heiden ZM; Lathem AP, Establishing the Hydride Donor Abilities of Main Group Hydrides. Organometallics 2015, 34, 1818–1827). Hammond’s postulate suggests that this would lead to a lower barrier (Alherz, A.; Lim, C.-H.; Hynes, J. T.; Musgrave, C. B., Predicting Hydride Donor Strength via Quantum Chemical Calculations of Hydride Transfer Activation Free Energy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 1278–1288). [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Sweany RL; Halpern J, Hydrogenation of alpha-methylstyrene by hydridopentacarbonylmanganese. Evidence for a free-radical mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1977, 99, 8335–8337; [Google Scholar]; (b) Bullock RM; Samsel EG, Hydrogen atom transfer reactions of transition-metal hydrides. Kinetics and mechanism of the hydrogenation of α-cyclopropylstyrene by metal carbonyl hydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 6886–6898; [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuo JL; Hartung J; Han A; Norton JR, Direct Generation of Oxygen-Stabilized Radicals by H•·Transfer from Transition Metal Hydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1036–1039; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Li G; Han A; Pulling ME; Estes DP; Norton JR, Evidence for Formation of a Co–H Bond from (H2O)2Co(dmgBF2)2 under H2: Application to Radical Cyclizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 14662–14665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Laugier J; Mathieu JP, Structure of bisacetylacetonatoiron(II) dihydrate. Acta Crystallogr. 1975, B31, 631; [Google Scholar]; (b) Buckingham DA; Gorges RC; Henry JT, Reaction of Pyridine with Iron(II) Acetylacetonate in Benzene Solutions. Aust. J. Chem 1967, 20, 497–502; [Google Scholar]; (c) Xue Z; Daran J-C; Champouret Y; Poli R, Ligand adducts of bis(acetylacetonato)-iron(II): a 1H NMR study. Inorg. Chem 2011, 50, 11543–11551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curran DP, Radical Addition Reactions. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, Trost BM, Ed. Pergamon: New York, 1991; Vol. 4, pp 715–778. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giese B, Formation of CC Bonds by Addition of Free Radicals to Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1983, 22, 753–764. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray RW; Hiller LK, Supporting electrolyte effects in nonaqueous electrochemistry. Coordinative relaxation reactions of reduced metal acetylacetonates in acetonitrile. Anal. Chem 1967, 39, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bortolamei N; Isse AA; Gennaro A, Estimation of standard reduction potentials of alkyl radicals involved in atom transfer radical polymerization. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 8312–8318. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Costentin C; Evans DH; Robert M; Savéant J-M; Singh PS, Electrochemical Approach to Concerted Proton and Electron Transfers. Reduction of the Water–Superoxide Ion Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 12490–12491; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Warren JJ; Tronic TA; Mayer JM, Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and its Implications. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 6961–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer JM, Proton-coupled electron transfer: A reaction chemist’s view. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem 2004, 55, 363–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reece SY; Nocera DG, Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Biology: Results from Synergistic Studies in Natural and Model Systems. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2009, 78, 673–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons EM; Hartwig JF, On the Interpretation of Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects in C-H Bond Functionalizations by Transition-Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Sambrano JR; Andrés J; Gracia L; Safont VS; Beltrán A, DFT study of the water-assisted tautomerization process between hydrated oxide, MO(H2O)+, and dihydroxide, M(OH)2+, cations (M=V, Nb and Ta). Chem. Phys. Lett 2004, 384, 56–62; [Google Scholar]; (b) Hratchian HP; Sonnenberg JL; Hay PJ; Martin RL; Bursten BE; Schlegel HB, Theoretical Investigation of Uranyl Dihydroxide: Oxo Ligand Exchange, Water Catalysis, and Vibrational Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 8579–8586; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jee J-E; Comas-Vives A; Dinoi C; Ujaque G; van Eldik R; Lledós A; Poli R, Nature of Cp*MoO2+ in Water and Intramolecular Proton-Transfer Mechanism by Stopped-Flow Kinetics and Density Functional Theory Calculations. Inorg. Chem 2007, 46, 4103–4113; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hayes JM; Deydier E; Ujaque G; Lledós A; Malacea-Kabbara R; Manoury E; Vincendeau S; Poli R, Ketone Hydrogenation with Iridium Complexes with “non N–H” Ligands: The Key Role of the Strong Base. ACS Catal 2015, 5, 4368–4376. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brocks JJ; Beckhaus H-D; Beckwith ALJ; Rüchardt C, Estimation of Bond Dissociation Energies and Radical Stabilization Energies by ESR Spectroscopy. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kütt A; Movchun V; Rodima T; Dansauer T; Rusanov EB; Leito I; Kaljurand I; Koppel J; Pihl V; Koppel I; Ovsjannikov G; Toom L; Mishima M; Medebielle M; Lork E; Röschenthaler G-V; Koppel IA; Kolomeitsev AA, Pentakis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl, a Sterically Crowded and Electron-withdrawing Group: Synthesis and Acidity of Pentakis(trifluoromethyl)benzene, -toluene, -phenol, and -aniline. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 2607–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Binstead RA; Meyer TJ, Hydrogen-atom transfer between metal complex ions in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 3287–3297. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Tilset M; Parker VD, Solution homolytic bond dissociation energies of organotransition-metal hydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 6711–6717; [Google Scholar]; (b) Estes DP; Vannucci AK; Hall AR; Lichtenberger DL; Norton JR, Thermodynamics of the Metal–Hydrogen Bonds in (η5-C5H5)M(CO)2H (M = Fe, Ru, Os). Organometallics 2011, 30, 3444–3447. [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Smith JM; Lachicotte RJ; Holland PL, N=N Bond Cleavage by a Low-Coordinate Iron(II) Hydride Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 15752–15753; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barton BE; Rauchfuss TB, Terminal hydride in [FeFe]-hydrogenase model has lower potential for H2 production than the isomeric bridging hydride. Inorg. Chem 2008, 47, 2261–2263; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schilter D; Camara JM; Huynh MT; Hammes-Schiffer S; Rauchfuss TB, Hydrogenase Enzymes and Their Synthetic Models: The Role of Metal Hydrides. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 8693–8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Poli R, Open shell organometallics: a general analysis of their electronic structure and reactivity. J. Organomet. Chem 2004, 689, 4291–4304; [Google Scholar]; (b) Poli R, Spin Crossover Reactivity In Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II, Reedijk J; Poeppelmeier K, Eds. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2013; Vol. 9, pp 481–500; [Google Scholar]; (c) Holland PL, Distinctive Reaction Pathways at Base Metals in High-Spin Organometallic Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 1696–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Rao PS; Hayon E, Redox potentials of free radicals. I. Simple organic radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1974, 96, 1287–1294; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fu Y; Liu L; Yu H-Z; Wang Y-M; Guo Q-X, Quantum-Chemical Predictions of Absolute Standard Redox Potentials of Diverse Organic Molecules and Free Radicals in Acetonitrile. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 7227–7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A piece of evidence that has been proposed in favor of the ET/PT mechanism is the ability to perform three-component couplings with aldehydes, which are more easily rationalized through the formation of a carbanion than a radical.6b Similarly, Cui has reported HAT alkene reactions in which acetyl or bromide displacement is proposed to proceed from an intermediate carbanion.6e However, the formation of these products can be explained without formation of an enolate. One possibility is that the electrophiles can coordinate to iron(II) (which is present in high concentration), activating them toward attack by a radical. This would give inner-sphere electron transfer that is concerted with C-C bond formation and iron abstraction of the leaving group. Though study of these three-component couplings is outside the scope of this paper, future studies will experimentally test the feasibility of such pathways.

- 38.Waidmann CR; Miller AJM; Ng C-WA; Scheuermann ML; Porter TR; Tronic TA; Mayer JM, Using combinations of oxidants and bases as PCET reactants: thermochemical and practical considerations. Energy Env. Sci 2012, 5, 7771–7780. [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Gentry EC; Knowles RR, Synthetic Applications of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 1546–1556; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chciuk TV; Anderson WR; Flowers RA, Interplay between Substrate and Proton Donor Coordination in Reductions of Carbonyls by SmI2–Water Through Proton-Coupled Electron-Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 15342–15352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.(a) Paradas M; Campaña AG; Jiménez T; Robles R; Oltra JE; Buñuel E; Justicia J; Cárdenas DJ; Cuerva JM, Understanding the Exceptional Hydrogen-Atom Donor Characteristics of Water in TiIII-Mediated Free-Radical Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12748–12756; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kolmar SS; Mayer JM, SmI2(H2O)n Reduction of Electron Rich Enamines by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 10687–10692; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gansäuer A; Behlendorf M; Cangönül A; Kube C; Cuerva JM; Friedrich J; van Gastel M, H2O Activation for Hydrogen-Atom Transfer: Correct Structures and Revised Mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3266–3270; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chciuk TV; Anderson WR; Flowers RA, High-Affinity Proton Donors Promote Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer by Samarium Diiodide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 6033–6036; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chciuk TV; Flowers RA, Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in the Reduction of Arenes by SmI2–Water Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11526–11531; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chciuk TV; Anderson WR; Flowers RA, Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in the Reduction of Carbonyls by Samarium Diiodide–Water Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 8738–8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Bezdek MJ; Guo S; Chirik PJ, Coordination-induced weakening of ammonia, water, and hydrazine X–H bonds in a molybdenum complex. Science 2016, 354, 730; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tarantino KT; Miller DC; Callon TA; Knowles RR, Bond-Weakening Catalysis: Conjugate Aminations Enabled by the Soft Homolysis of Strong N–H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6440–6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oyeyemi VB; Dieterich JM; Krisiloff DB; Tan T; Carter EA, Bond Dissociation Energies of C10 and C18 Methyl Esters from Local Multireference Averaged-Coupled Pair Functional Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 3429–3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng J; Wang D; Cui S, Fe-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Unactivated Alkenes with β-Nitroalkenes. Org. Lett 2015, 17, 4572–4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng J; Qi J; Cui S, Fe-Catalyzed Olefin Hydroamination with Diazo Compounds for Hydrazone Synthesis. Org. Lett 2016, 18, 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saladrigas M; Bosch C; Saborit GV; Bonjoch J; Bradshaw B, Radical Cyclization of Alkene-Tethered Ketones Initiated by Hydrogen-Atom Transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen Y; Qi J; Mao Z; Cui S, Fe-Catalyzed Hydroalkylation of Olefins with para-Quinone Methides. Org. Lett 2016, 18, 2722–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.(a) Allan LEN; MacDonald JP; Nichol GS; Shaver MP, Single Component Iron Catalysts for Atom Transfer and Organometallic Mediated Radical Polymerizations: Mechanistic Studies and Reaction Scope. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1249–1257; [Google Scholar]; (b) Poli R; Shaver MP, Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) and Organometallic Mediated Radical Polymerization (OMRP) of Styrene Mediated by Diaminobis(phenolato)iron(II) Complexes: A DFT Study. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 7580–7590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.