Abstract

No network meta‐analysis has examined the relative effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression, while this is a very important clinical issue. We conducted systematic searches in bibliographical databases to identify randomized trials in which a psychotherapy and a pharmacotherapy for the acute or long‐term treatment of depression were compared with each other, or in which the combination of a psychotherapy and a pharmacotherapy was compared with either one alone. The main outcome was treatment response (50% improvement between baseline and endpoint). Remission and acceptability (defined as study drop‐out for any reason) were also examined. Possible moderators that were assessed included chronic and treatment‐resistant depression and baseline severity of depression. Data were pooled as relative risk (RR) using a random‐effects model. A total of 101 studies with 11,910 patients were included. Depression in most studies was moderate to severe. In the network meta‐analysis, combined treatment was more effective than psychotherapy alone (RR=1.27; 95% CI: 1.14‐1.39) and pharmacotherapy alone (RR=1.25; 95% CI: 1.14‐1.37) in achieving response at the end of treatment. No significant difference was found between psychotherapy alone and pharmacotherapy alone (RR=0.99; 95% CI: 0.92‐1.08). Similar results were found for remission. Combined treatment (RR=1.23; 95% CI: 1.05‐1.45) and psychotherapy alone (RR=1.17; 95% CI: 1.02‐1.32) were more acceptable than pharmacotherapy. Results were similar for chronic and treatment‐resistant depression. The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy seems to be the best choice for patients with moderate depression. More research is needed on long‐term effects of treatments (including cost‐effectiveness), on the impact of specific pharmacological and non‐pharmacological approaches, and on the effects in specific populations of patients.

Keywords: Depression, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, combined treatment, cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal therapy, antidepressants, acceptability, chronic depression, treatment‐resistant depression, network meta‐analysis

Mental disorders are a major cause of global health burden, accounting for 23% of years lived with disability1. With 350 million people affected in the world, depressive disorder is the second leading cause of global burden2. The high direct and indirect costs of major depression are substantially due to significant deficits in treatment provision3. There are a number of efficacious interventions for depressive disorder, and the key challenge is how best to implement currently available effective treatments4.

It is well‐established that psychotherapies and pharmacological therapies are effective in the treatment of adult depression. Psychotherapies have shown superior effects compared to control conditions in numerous clinical trials. Moreover, different psychotherapeutic types – e.g., cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy – have comparable outcomes in depression5. Another large body of research has shown that different classes of antidepressants are effective in the treatment of depression6, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and several others.

Although the absolute effectiveness of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies is well documented, the evidence supporting their relative effects remains inconclusive. Conventional meta‐analyses of trials directly comparing psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies have suggested that, as classes of treatments, they have comparable effects, with no or only minor differences7, 8, although there may be some influence of placebo effects9, sponsorship bias10, and possibly the superiority of some medications over others6. Other pairwise meta‐analyses have found that the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may be more effective than either of these alone11, 12, although the evidence is not conclusive13, 14. Moreover, some studies suggest that the two monotherapies result in differential effects over long‐term follow‐ups, with psychotherapy having enduring effects on depression when pharmacotherapy is discontinued.

Several issues regarding the differential effects of combined treatment, psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies remain unsolved. Existing meta‐analyses have compared only two interventions at a time: psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy15, combined treatment vs. psychotherapy14, and combined treatment vs. pharmacotherapy11, 12. To get a better understanding of the relative effectiveness of these treatments, it is necessary to combine direct and indirect evidence from all clinical trials. Network meta‐analyses can combine multiple comparisons in one analysis, are able to use direct and indirect evidence, and thus make optimal use of all available evidence. These analyses consequently make better estimates of the differences between treatments, have more statistical power to examine moderators of outcome, and can present consolidated comparisons among alternative treatments16.

Further important questions have not yet been answered. The majority of randomized trials in this field may be prone to methodological bias; no information is available for different populations of patients (e.g., mild vs. chronic or treatment‐resistant depression); and acceptability of the treatments has not been examined extensively so far.

We therefore conducted a network meta‐analysis based on randomized trials in which a psychotherapy and a pharmacotherapy for depression were compared with each other, or in which the combination of a psychotherapy and a pharmacotherapy was compared with either one alone.

METHODS

Identification and selection of studies

The protocol for this network meta‐analysis was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42018114961). For the identification of studies, we used a database of randomized trials examining the effects of psychotherapies in depression, that was developed through a comprehensive literature search (from 1966 to January 1, 2018)17. Four major bibliographical databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library) were searched by combining index and text words indicative of depression and psychotherapies, with filters for randomized controlled trials. All records and full texts were screened by two independent researchers. Any disagreement was solved through discussion.

We included studies in which a psychotherapy and a pharmacological treatment for depression were directly compared with each other, and studies in which the combination of a psychotherapy and a pharmacological treatment was compared with either one alone. When these trials included pill placebo or the combination of psychotherapy and pill placebo, we included such arms as well.

We defined psychotherapy as “the informed and intentional application of clinical methods and interpersonal stances derived from established psychological principles for the purpose of assisting people to modify their behaviors, cognitions, emotions and/or other personal characteristics in directions that the participants deem desirable”18. We allowed any type of psychotherapy8 in any delivery format (individual, group, face‐to‐face, telephone, or self‐help including Internet) and any type of oral antidepressant treatment within the therapeutic dose range.

We only included studies recruiting patients with acute depressive disorder according to modern operationalized and validated criteria. Comorbid mental or somatic disorders were not excluded. We did not set a maximum or minimum concerning the length of treatment or the duration of follow‐up7.

When a study contained two or more arms to be included in the same node (for example, when one study compared two types of psychotherapy with one pharmacotherapy condition), we considered them as separate comparisons and subdivided the comparisons appropriately in order to avoid double counting19. We also conducted sensitivity analyses in which the two comparable arms were pooled into one arm.

Risk of bias and data extraction

Two independent researchers assessed the risk of bias of included studies using four criteria of the Cochrane tool20. Disagreements were solved through discussion. Pharmacotherapy studies were also assessed regarding the use of therapeutic dose6 and the titration schedule (i.e., therapeutic dose achieved within three weeks). The pharmacotherapy was deemed adequate if both criteria were met. Psychotherapies were assessed with respect to using a treatment manual, provision of therapy by specially trained therapists, and verification of treatment integrity21, 22.

We also coded participant characteristics (type of depressive disorder, recruitment method, target group); the type of psychotherapy and the number of treatment sessions; the type of medication; whether or not a placebo condition was included in the trial (because then patients were blinded for medication or placebo)9; the time between pre‐test and post‐test (in weeks); and the country where the study was conducted.

Outcome measures

Treatment response, defined as a 50% reduction in depressive symptomatology according to a standardized rating scale, was chosen as the primary outcome. When not reported, we imputed response rate using a validated method23. The timepoint for the primary outcome was the end of the therapy. We also calculated response rates at follow‐up of 6 months, between 6 and 12 months, and more than 12 months.

Remission rate was defined as the number of patients with a score for depressive symptoms below a specific cut‐off on a validated rating scale. We also calculated the standardized mean difference (SMD) between pairs of conditions, expressing the size of the intervention effect in each study relative to the variability observed in that study. Acceptability of the treatment formats was operationalized as study drop‐out for any reason during the acute phase treatment.

Meta‐analyses

We conducted pairwise meta‐analyses for all comparisons, using a random effects pooling model. To quantify heterogeneity, we calculated the I2 statistic with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using the non‐central chi‐squared‐based approach within the heterogi module for Stata24. We tested for small study effects, including publication bias, with Egger's test25.

The comparative effectiveness was evaluated using the network meta‐analysis methodology. First, we summarized the geometry of the network of evidence using network plots for the main outcome26. Second, we conducted contrast‐based analyses to assess comparative efficacy and acceptability27. Given the expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity of treatment effects among the studies, we adopted the multivariate random effect models28. Relative risks (RRs) and SMDs were reported with their 95% CIs. The ranking of treatment formats was estimated according to the “surface under the cumulative ranking” (SUCRA), based on the estimated multivariate random effects models26. We checked the consistency of the network using tests of local and global inconsistency29, 30.

Further analyses

We conducted separate pairwise and network meta‐analyses for studies examining chronic or treatment‐resistant depression. We also selected studies that reported the baseline score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D)31 and examined in a meta‐regression analysis whether baseline severity was associated with outcome. We then conducted separate pairwise and network meta‐analyses for mild, moderate and severe depression according to the baseline severity of the sample, using the thresholds proposed by Zimmerman et al32. In addition, we performed a multivariate meta‐regression analysis to examine possible sources of heterogeneity.

We carried out a series of sensitivity analyses with studies in which pharmacotherapy was optimized; those in which psychotherapy met all the above‐mentioned quality criteria; those at low risk of bias; and those in which no placebo was included. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted in which all patients randomized to different arms in the same node (e.g., two types of psychotherapy) in a given study were pooled, so that there was only one arm for each condition.

All analyses were conducted in Stata/SE 14.2.

RESULTS

Studies included and their characteristics

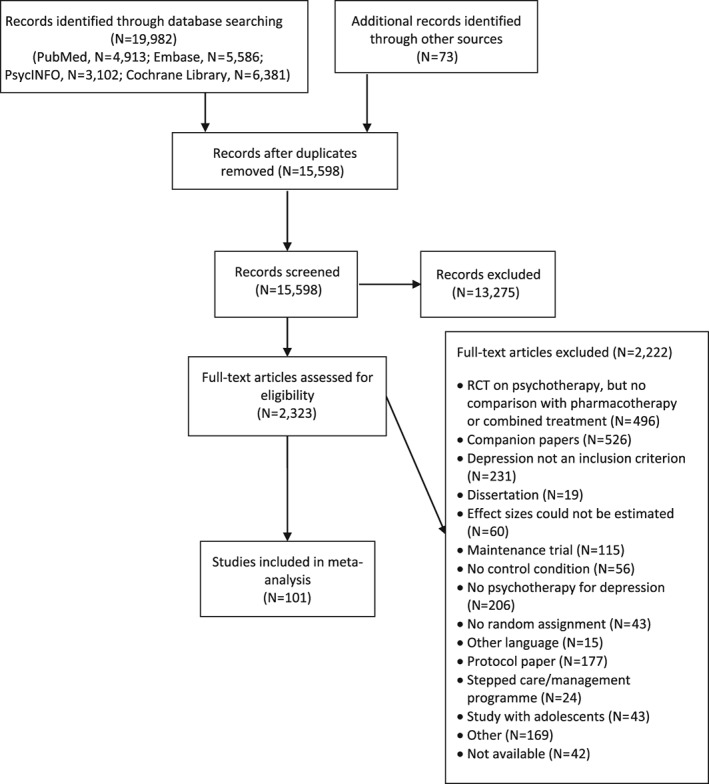

After examining a total of 19,982 abstracts (15,598 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 2,323 full‐text papers for further consideration. The PRISMA flow chart describing the inclusion process is presented in Figure 1. A total of 101 studies met inclusion criteria (11,910 participants overall: 2,587 randomized to combined treatment, 3,625 to psychotherapy, 4,769 to pharmacotherapy, 632 to placebo and 297 to psychotherapy plus placebo)33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for inclusion of studies. RCT – randomized clinical trial

Selected characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. In 12 studies two types of psychotherapy were examined as separate arms; in one study two types of pharmacotherapy were included62; and in one other study the therapy was separated into two arms with different providers (general practitioners or nurses)105. In total, 115 comparisons were available in the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Conditions | Psychotherapy | Therapy quality | Pharmacotherapy | Adequate therapy | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadpanah et al33 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | MBCT | – – – | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | Stress management | – – – | SSRI | Yes | + + + + | |

| Altamura et al34 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + – | SSRI | Yes | + – + – |

| Appleby et al35 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo vs. psychotherapy + placebo | CBT | – + – | SSRI | No | + – + + |

| Ashouri et al36 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | Other | No | – – sr – |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | MBCT | – – – | Other | No | – – sr – | |

| Barber et al37 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | DYN | + + – | Other | Yes | + – + + |

| Barrett et al38 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | PST | + + – | SSRI | Yes | + – + – |

| Beck et al39 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | CBT | + + – | TCA | Yes | – – – – |

| Bedi et al40 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | Not specified | – + – | Other | No | – + sr – |

| Bellack et al41 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | Social skills | + + – | TCA | Yes | – – + – |

| Bellino et al42 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + – | SSRI | Yes | – – + – |

| Blackburn et al43 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | TCA | Yes | – – – – |

| Blackburn & Moore44 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – + – | Other | No | – – + – |

| Bloch et al45 | Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | DYN | – + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Blom et al46 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | IPT | + + + | Other | Yes | – – + + |

| Browne et al47 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + – |

| Burnand et al48 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | DYN | – + + | Other | Yes | – – + – |

| Chibanda et al49 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | PST | + + + | TCA | No | + – sr – |

| Corruble et al50 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | Social rhythms | + + + | Other | No | + + + – |

| Covi & Lipman51 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | CBT | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – sr – |

| David et al52 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | – – + + |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | REBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | – – + + | |

| De Jonghe et al53 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | DYN | + + + | Other | No | – – + + |

| De Jonghe et al54 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | DYN | + + + | Other | No | – – + – |

| de Mello et al55 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + – | Other | Yes | – – + – |

| Dekker et al56 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | DYN | + + + | Other | No | – – + – |

| Denton et al57 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | EFT | + + + | Other | No | + + + + |

| DeRubeis et al58 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | – – + + |

| Dimidjian et al59 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | BAT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + – + + |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + – + + | |

| Dozois et al60 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | No | – + – – |

| Dunlop et al61 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – – | SSRI | Yes | – + + – |

| Dunlop et al62 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | Yes | + + + + |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + | |

| Dunn63 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | Other | No | – – sr – |

| Dunner et al64 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | – – + – |

| Eisendrath et al65 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | MBCT | + + + | Other | No | + + + + |

| Elkin et al66 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | CBT | + + + | TCA | Yes | + + + + |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | IPT | + + + | TCA | Yes | + + + + | |

| Faramarzi et al67 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – – | SSRI | Yes | – – sr – |

| Finkenzeller et al68 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + – – | SSRI | Yes | + – + + |

| Frank et al69 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | – – + + |

| Gater et al70 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | Social group | + + + | Other | No | + + + + |

| Gaudiano et al71 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | ABT | + + + | Other | No | – – + + |

| Hautzinger et al72 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | TCA | Yes | – – + + |

| Hegerl et al73 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | CBT | + – + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Hellerstein et al74 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | Cognitive‐interpersonal | + + + | SSRI | Yes | – – – + |

| Hollon et al75 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – + + |

| Hollon et al76 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | No | + + + + |

| Hsiao et al77 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | BMS | + + – | Other | No | + – sr + |

| Husain et al78 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – – | Other | No | + + + + |

| Jarrett et al79 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | CBT | + + + | Other | Yes | – + + + |

| Keller et al80 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBASP | + + + | Other | Yes | + + + + |

| Kennedy et al81 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | Yes | – – – – |

| Lam et al82 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Lesperance et al83 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo vs. psychotherapy + placebo | IPT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Lynch et al84 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | DBT | – + + | Other | No | – – – – |

| Macaskill & Macaskill85 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – – | TCA | Yes | – – – – |

| Maina et al86 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | DYN | – + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Maldonado López87 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | Other | No | – – + – |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | BAT | – – – | Other | No | – – + – | |

| Maldonado López 88 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | Other | No | – – + – |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | BAT | – – – | Other | No | – – + – | |

| Markowitz et al89 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | SUP | + + + | TCA | Yes | + + + + |

| Markowitz et al90 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | SUP | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + | |

| Marshall et al91 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | No | – – – – |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + + | Other | No | – – – – | |

| Martin et al92 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + – | Other | Yes | – – – + |

| McKnight et al93 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + – | TCA | No | – – sr – |

| McLean & Hakstian94 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – sr – |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | DYN | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – sr – | |

| Menchetti et al95 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + – – | SSRI | No | + + – + |

| Milgrom et al96 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – + | SSRI | Yes | + + sr + |

| Miranda et al97 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | No | + + + + |

| Misri et al98 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + – | SSRI | No | + – + + |

| Mitchell et al99 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | PST | + – + | Other | No | + + + + |

| Mohr et al100 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – + | SSRI | Yes | – – – + |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | SEG | + – + | SSRI | Yes | – – – + | |

| Moradveisi et al101 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | BAT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Murphy et al102 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | CBT | + + + | TCA | Yes | + + – + |

| Murphy et al103 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | TCA | Yes | + – – – |

| Mynors‐Wallis et al104 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | PST | + + – | TCA | Yes | – + + – |

| Mynors‐Wallis et al105 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | PST | + – + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | PST | + – + | SSRI | Yes | + + + + | |

| Naeem et al106 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + sr + |

| Parker et al107 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + – | Other | Yes | + + + – |

| Petrak et al108 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + – | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Quilty et al109 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | No | – – – + |

| Ravindran et al110 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo vs. psychotherapy + placebo | CBT | + + – | SSRI | Yes | + + + – |

| Reynolds et al111 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo vs. psychotherapy + placebo | IPT | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – + + |

| Rodriguez Vega et al112 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | Narrative | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + + sr + |

| Roth et al113 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | Self‐control | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – – – |

| Rush et al114 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – + | TCA | Yes | – – + + |

| Rush & Watkins115 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | CBT | + – + | Other | No | – – sr + |

| Salminen et al116 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | DYN | – + – | SSRI | Yes | – – – + |

| Schiffer & Wineman117 | Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | Three types | – – – | TCA | Yes | – – – – |

| Schramm et al118 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBASP | + + + | SSRI | Yes | + – + + |

| Schulberg et al119 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + + | TCA | Yes | – – + + |

| Scott & Freeman120 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + – | TCA | Yes | – + + – |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | SUP | – – – | TCA | Yes | – + + – | |

| Shamsaei et al121 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – – – | SSRI | Yes | + – sr – |

| Sharp et al122 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | SUP | – + + | Other | No | + + sr + |

| Souza et al123 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + + + | Other | No | + + + + |

| Stravynski et al124 | Combined vs. psychotherapy | CBT | – – – | TCA | Yes | – – + – |

| Targ et al125 | Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | PST | – – + | SSRI | Yes | – – + – |

| Thompson et al126 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – – | TCA | No | – – – + |

| Weissman et al127 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | IPT | + – – | TCA | Yes | – – + – |

| Wiles et al128 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + – + | Other | No | + + sr + |

| Wiles et al129 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | + + + | Other | No | + + sr + |

| Williams et al130 | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | PST | + + – | SSRI | Yes | + + + + |

| Wilson131 | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy vs. placebo vs. psychotherapy + placebo | BAT | + – – | TCA | Yes | – – + – |

| Zisook et al132 | Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | SUP | – – – | SSRI | Yes | – – + + |

| Zu et al133 | Combined vs. psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | CBT | – + + | SSRI | Yes | + – + – |

Risk of bias: + means low risk, – means high or unclear risk, “sr” means that only a self‐report instrument was used

ABT – acceptance‐based behavior therapy, BAT – behavioral activation therapy, BMS – body‐mind‐spirit therapy, CBASP – cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, CBT – cognitive behavior therapy, CT – cognitive therapy, DBT – dialectical behavioral therapy, DYN – psychodynamic therapy, EFT – emotion‐focused therapy, IPT – interpersonal psychotherapy, MBCT – mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, PST – problem‐solving therapy, REBT – rational‐emotive behavior therapy, SEG – supportive‐expressive group psychotherapy, SUP – supportive therapy, SSRI – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, TCA – tricyclic antidepressant

The aggregated characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2. In brief, 47 trials recruited patients exclusively from clinical samples, and 75 were aimed at unselected adults. Thirteen studies were aimed at patients with chronic or treatment‐resistant depression. CBT was the most commonly used psychotherapy (48 trials); an individual format was used in 81 psychotherapy studies; 45 trials met all three quality criteria. SSRIs were the most frequently used medications; pharmacotherapy was judged adequate in 67 trials. The time from pre‐ to post‐test ranged from 4 to 36 weeks, with the majority of comparisons (78%) ranging from 8 to 16 weeks. In 36 of 51 trials reporting the mean baseline HAM‐D score, the severity of depression was moderate.

Table 2.

Description of included studies and distribution of potential effect modifiers

| All studies | Combined vs. psychotherapy | Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Patients | |||||||||

| Recruitment | Community | 35 | 34.7 | 9 | 40.9 | 14 | 29.2 | 21 | 36.8 |

| Clinical | 47 | 46.5 | 11 | 50.0 | 28 | 58.3 | 26 | 45.6 | |

| Other | 19 | 18.8 | 2 | 9.1 | 6 | 12.5 | 10 | 17.5 | |

| Target group | Adults | 75 | 74.3 | 17 | 77.3 | 33 | 68.8 | 46 | 80.7 |

| Specific group | 26 | 25.7 | 5 | 22.7 | 15 | 31.3 | 11 | 19.3 | |

| Chronic or treatment‐resistant depression | 13 | 12.9 | 3 | 13.6 | 11 | 22.9 | 5 | 8.8 | |

| Psychotherapy | |||||||||

| Type | CBT | 48 | 47.5 | 12 | 54.5 | 21 | 43.8 | 31 | 54.4 |

| Other | 52 | 52.5 | 10 | 45.5 | 27 | 56.3 | 26 | 45.6 | |

| Format | Individual | 81 | 80.2 | 15 | 68.2 | 38 | 79.2 | 47 | 82.5 |

| Group/mixed | 20 | 19.8 | 7 | 31.8 | 10 | 20.8 | 10 | 17.5 | |

| Optimized | 45 | 44.6 | 11 | 50.0 | 22 | 45.8 | 26 | 45.6 | |

| Pharmacotherapy | |||||||||

| Type | SSRI | 38 | 37.6 | 6 | 27.3 | 17 | 35.4 | 24 | 42.1 |

| TCA | 26 | 25.7 | 11 | 50.0 | 11 | 22.9 | 15 | 26.3 | |

| Other | 37 | 36.6 | 5 | 22.7 | 20 | 41.7 | 18 | 31.6 | |

| Optimized | 67 | 66.3 | 18 | 81.8 | 28 | 58.3 | 43 | 75.4 | |

| General study characteristics | |||||||||

| Country | US | 53 | 52.5 | 14 | 63.6 | 23 | 47.9 | 29 | 50.9 |

| Europe | 32 | 31.7 | 5 | 22.7 | 15 | 31.3 | 20 | 35.1 | |

| Other | 16 | 15.8 | 3 | 13.6 | 10 | 20.8 | 8 | 14.0 | |

| Low risk of bias | 28 | 27.7 | 5 | 22.7 | 17 | 35.4 | 13 | 22.8 | |

CBT – cognitive behavior therapy, SSRI – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, TCA – tricyclic antidepressant

There was moderate to high risk of bias in most trials. A total of 48 studies reported an adequate sequence generation; 40 reported allocation to conditions by an independent (third) party; and 81 reported blinding of outcome assessors or used only self‐report outcomes. Intention‐to‐treat analyses were conducted in 58 studies. Twenty‐three studies met all four quality criteria (28 when self‐report was rated as low risk of bias), 19 met three criteria, another 19 met two criteria, and the remaining 40 studies met one or none of the criteria.

Meta‐analyses

Table 3 shows the main results of the pairwise meta‐analyses for the response rates. Combined treatment was more effective than both psychotherapy alone (RR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.09‐1.43) and pharmacotherapy alone (RR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.12‐1.43). The difference between psychotherapy alone and pharmacotherapy alone was not significant (RR=0.98, 95% CI: 0.91‐1.06). Heterogeneity was low to moderate in most comparisons. In the comparisons with more than 10 studies, only heterogeneity of combined treatment versus pharmacotherapy was higher than 50%. Egger's test was only significant for combined treatment versus pharmacotherapy (p=0.02) and for combined treatment versus psychotherapy plus placebo (p=0.02).

Table 3.

Results of pairwise and network meta‐analyses

| N | Pairwise meta‐analyses | Network meta‐analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | I2 | 95% CI | Egger | RR | 95% CI | ||

| Response | ||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 19 | 1.25 | 1.09‐1.43 | 44 | 0‐66 | 0.36 | 1.27 | 1.14‐1.39 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 46 | 1.27 | 1.12‐1.43 | 58 | 39‐69 | 0.02 | 1.25 | 1.14‐1.37 |

| Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 10 | 1.19 | 0.95‐1.52 | 39 | 0‐69 | 0.02 | 1.30 | 1.06‐1.59 |

| Combined vs. placebo | 4 | 1.15 | 0.73‐1.79 | 60 | 0‐84 | 0.39 | 1.47 | 1.20‐1.75 |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 59 | 0.98 | 0.91‐1.06 | 41 | 16‐57 | 0.38 | 0.99 | 0.92‐1.08 |

| Psychotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 2 | 0.88 | 0.60‐1.30 | 16 | NA | NA | 1.03 | 0.84‐1.27 |

| Psychotherapy vs. placebo | 8 | 1.20 | 0.93‐1.59 | 46 | 0‐74 | 0.67 | 1.16 | 0.98‐1.39 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 6 | 1.05 | 0.76‐1.45 | 53 | 0‐79 | 0.45 | 1.04 | 0.85‐1.27 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | 12 | 1.25 | 1.09‐1.45 | 0 | 0‐50 | 0.68 | 1.18 | 0.99‐1.39 |

| Psychotherapy + placebo vs. placebo | 4 | 1.00 | 0.76‐1.30 | 0 | 0‐68 | 0.29 | 0.88 | 0.69‐1.12 |

| Remission | ||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 15 | 1.20 | 1.02‐1.41 | 25 | 0‐59 | 0.76 | 1.22 | 1.08‐1.39 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 25 | 1.28 | 1.10‐1.52 | 57 | 27‐72 | 0.22 | 1.23 | 1.09‐1.39 |

| Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 6 | 1.18 | 0.71‐1.92 | 67 | 0‐84 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 0.82‐1.45 |

| Combined vs. placebo | 2 | 1.52 | 1.02‐2.22 | 0 | NA | NA | 1.59 | 1.27‐2.00 |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 47 | 1.01 | 0.93‐1.10 | 29 | 0‐50 | 0.90 | 1.01 | 0.93‐1.10 |

| Psychotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 1 | 0.66 | 0.40‐1.05 | NA | NA | NA | 0.89 | 0.67‐1.19 |

| Psychotherapy vs. placebo | 7 | 1.37 | 1.05‐1.79 | 41 | 0‐74 | 0.03 | 1.30 | 1.05‐1.59 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 4 | 0.81 | 0.32‐2.04 | 84 | 47‐92 | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.67‐1.19 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | 9 | 1.33 | 1.10‐1.64 | 22 | 0‐64 | 0.04 | 1.28 | 1.05‐1.59 |

| Psychotherapy + placebo vs. placebo | 2 | 1.25 | 0.76‐2.04 | 0 | NA | NA | 0.69 | 0.49‐0.96 |

| Acceptability | ||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 18 | 1.08 | 0.92‐1.28 | 0 | 0‐44 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.89‐1.26 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 41 | 1.29 | 1.13‐1.47 | 0 | 0‐33 | 0.74 | 1.23 | 1.05‐1.45 |

| Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 9 | 0.96 | 0.59‐1.58 | 18 | 0‐62 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.66‐1.46 |

| Combined vs. placebo | 4 | 1.35 | 0.56‐3.27 | 24 | 0‐75 | 0.12 | 1.25 | 0.94‐1.66 |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 58 | 1.16 | 1.02‐1.31 | 28 | 0‐48 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 1.02‐1.32 |

| Psychotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 2 | 0.54 | 0.13‐2.36 | 36 | NA | NA | 0.93 | 0.62‐1.38 |

| Psychotherapy vs. placebo | 8 | 1.34 | 0.86‐2.09 | 62 | 0‐81 | 0.15 | 1.18 | 0.91‐1.53 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 7 | 0.72 | 0.43‐1.21 | 27 | 0‐69 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.50‐1.19 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | 12 | 0.98 | 0.72‐1.33 | 40 | 0‐68 | 0.38 | 1.02 | 0.79‐1.30 |

| Psychotherapy + placebo vs. placebo | 4 | 1.06 | 0.57‐1.95 | 0 | 0‐68 | 0.31 | 0.79 | 0.51‐1.21 |

| Standardized mean difference (SMD) | N | SMD | 95% CI | I 2 | 95% CI | Egger | SMD | 95% CI |

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 19 | 0.15 | –0.05 to 0.35 | 69 | 45‐79 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.14‐0.45 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 41 | 0.37 | 0.23‐0.53 | 68 | 54‐76 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.20‐0.47 |

| Combined vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 7 | 0.07 | –0.20 to 0.34 | 12 | 0‐63 | 0.61 | 0.16 | –0.18 to 0.49 |

| Combined vs. placebo | 2 | 0.08 | –0.40 to 0.55 | 0 | NA | NA | 0.43 | 0.10‐0.76 |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 50 | 0.00 | –0.13 to 0.12 | 68 | 55‐75 | 0.03 | 0.04 | –0.09 to 0.16 |

| Psychotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 2 | –0.19 | –0.57 to 0.18 | 0 | NA | NA | –0.14 | –0.49 to 0.21 |

| Psychotherapy vs. placebo | 4 | 0.19 | –0.37 to 0.75 | 82 | 34‐91 | 0.89 | 0.13 | –0.19 to 0.45 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy + placebo | 4 | –0.24 | –0.58 to 0.10 | 16 | 0‐73 | 0.76 | –0.18 | –0.52 to 0.16 |

| Pharmacotherapy vs. placebo | 6 | 0.19 | –0.13 to 0.50 | 48 | 0‐77 | 0.84 | 0.10 | –0.22 to 0.41 |

| Psychotherapy + placebo vs. placebo | 2 | –0.11 | –0.59 to 0.38 | 0 | NA | NA | –0.27 | –0.71 to 0.16 |

RR – relative risk, NA – not available

Significant results are highlighted in bold prints

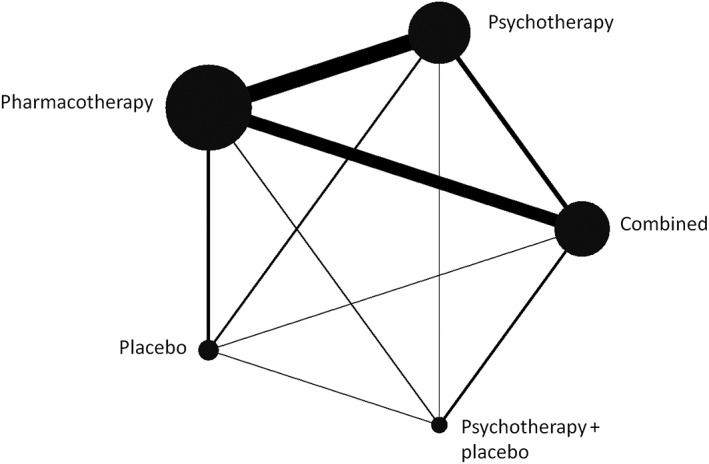

The network for response rates is graphically represented in Figure 2. The main results of the network meta‐analysis are presented in Table 3. Combined treatment was superior to either psychotherapy alone or pharmacotherapy alone in terms of response (RR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.14‐1.39, and RR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.14‐1.37, respectively), remission (RR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.08‐1.39 and RR=1.23, 95% CI: 1.09‐1.39), and SMD (0.30, 95% CI: 0.14‐0.45 and 0.33, 95% CI: 0.20‐0.47). No significant difference was found between psychotherapy alone and pharmacotherapy alone concerning response (RR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.92‐1.08), remission (RR=1.01, 0.93‐1.10), and SMD (SMD=0.04, 95% CI: –0.09 to 0.16). Acceptability was significantly better for combined treatment compared with pharmacotherapy (RR=1.23, 95% CI: 1.05‐1.45), as well as for psychotherapy compared with pharmacotherapy (RR=1.17, 95% CI: 1.02‐1.32).

Figure 2.

Network plot for response to psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, combination of psychotherapy and placebo, and placebo only in depression. The nodes and edges are weighted according to the number of participants and comparisons.

In the relatively few relevant studies included in the network meta‐analysis, response rate was significantly higher for combined treatment compared to psychotherapy plus pill placebo (RR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.06‐1.59) and for combined treatment compared to pill placebo (RR=1.47, 95% CI: 1.20‐1.75). Remission rate was significantly higher for combined treatment compared to pill placebo (RR=1.59, 95% CI: 1.27‐2.00). Combined treatment also resulted in a significantly higher SMD than pill placebo (0.43, 95% CI: 0.10‐0.76).

The consistency of the network was examined using the loop‐specific approach. No inconsistency factors were found to be significant, although this cannot be considered as evidence for the absence of inconsistency, because of low power in some of the loops, especially in the presence of large heterogeneity in pairwise comparisons. The design‐by‐treatment interaction model did not indicate global inconsistency in the network (X2=10.51, df=10, p for the null hypothesis of consistency in the network: 0.40).

In the SUCRA analyses, combined treatment ranked clearly best for response (99.9), remission (93.0) and SMD (95.6), as well as for acceptability (78.7). Psychotherapy ranked better than pharmacotherapy for remission (45.0 vs. 40.8), SMD (43.5 vs. 29.1) and acceptability (63.2 vs. 17.4), whereas pharmacotherapy ranked better than psychotherapy for response (54.2 vs. 49.6).

Further analyses

The results of the sensitivity analyses are reported in Table 4. The main outcomes were comparable across all analyses, with combined treatment being superior to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone, and no significant difference between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

Table 4.

Results of sensitivity analyses (all with response as outcome)

| Pairwise meta‐analyses | Network meta‐analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | RR | 95% CI | I2 | 95% CI | Egger | RR | 95% CI | χ2 (df), p | |

| Optimized pharmacotherapy | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 15 | 1.27 | 1.08‐1.49 | 53 | 0‐73 | 0.38 | 1.20 | 1.08‐1.35 | 1.20 (3), 0.75 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 25 | 1.16 | 1.02‐1.33 | 52 | 15‐68 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 1.06‐1.33 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 45 | 0.99 | 0.91‐1.08 | 44 | 14‐60 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 0.91‐1.08 | |

| Optimized psychotherapy | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 9 | 1.33 | 1.18‐1.52 | 14 | 0‐60 | 0.42 | 1.25 | 1.08‐1.47 | 0.47 (3), 0.93 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 19 | 1.27 | 1.06‐1.49 | 72 | 53‐81 | 0.33 | 1.27 | 1.10‐1.45 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 30 | 1.00 | 0.90‐1.11 | 49 | 15‐66 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.89‐1.12 | |

| Low risk of bias (self‐report rated as low risk) | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 6 | 1.33 | 0.98‐1.79 | 49 | 0‐78 | 0.24 | 1.45 | 1.16‐1.82 | 1.06 (3), 0.79 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 17 | 1.32 | 1.02‐1.67 | 70 | 45‐80 | 0.88 | 1.27 | 1.05‐1.54 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 16 | 0.87 | 0.76‐0.99 | 41 | 0‐66 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.74‐1.03 | |

| Low risk of bias (self‐report rated as high risk) | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 5 | 1.52 | 1.32‐1.75 | 0 | 0‐64 | 0.59 | 1.43 | 1.15‐1.79 | 0.02 (3), 1.00 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 13 | 1.27 | 0.96‐1.67 | 70 | 39‐81 | 0.87 | 1.23 | 1.02‐1.49 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 14 | 0.88 | 0.79‐1.00 | 30 | 0‐62 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.74‐1.01 | |

| Placebo controlled excluded | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 16 | 1.28 | 1.10‐1.49 | 50 | 0‐70 | 0.56 | 1.32 | 1.18‐1.47 | 0.66 (3), 0.88 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 39 | 1.30 | 1.15‐1.47 | 58 | 37‐70 | 0.02 | 1.27 | 1.15‐1.41 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 48 | 0.94 | 0.87‐1.03 | 40 | 10‐57 | 0.68 | 0.96 | 0.88‐1.05 | |

| One effect size per study | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 19 | 1.25 | 1.09‐1.43 | 46 | 0‐67 | 0.40 | 1.25 | 1.12‐1.39 | 0.27 (3), 0.97 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 43 | 1.27 | 1.12‐1.43 | 61 | 43‐71 | 0.02 | 1.25 | 1.14‐1.37 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 50 | 0.99 | 0.90‐1.08 | 50 | 26‐63 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.92‐1.09 | |

RR – relative risk

Significant results are highlighted in bold prints

We conducted separate pairwise and network meta‐analyses limited to studies on chronic or treatment‐resistant depression (only for response), whose results are presented in Table 5. Although the number of studies was relatively small, the findings were comparable to the main analyses, with superior effects for combined treatment versus psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone (RR=1.59, 95% CI: 1.23‐2.04 and RR=1.39, 95% CI: 1.15‐1.67), and comparable effects for psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (RR=0.87, 95% CI: 0.68‐1.10).

Table 5.

Results of analyses focusing on chronic/treatment‐resistant and mild/moderate/severe depression (all with response as outcome)

| Pairwise meta‐analyses | Network meta‐analyses | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | RR | 95% CI | I2 | 95% CI | Egger | RR | 95% CI | χ2 (df), p | |

| Chronic or treatment‐resistant depression | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 3 | 1.45 | 1.16‐1.79 | 55 | 0‐86 | 1.00 | 1.59 | 1.23‐2.04 | 2.47 (2), 0.29 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 10 | 1.41 | 1.12‐1.75 | 73 | 41‐84 | 0.37 | 1.39 | 1.15‐1.67 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 6 | 0.84 | 0.70‐1.00 | 25 | 0‐70 | 0.37 | 0.87 | 0.68‐1.10 | |

| Severe depression | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 2 | 1.35 | 0.85‐2.17 | 65 | NA | NA | 1.33 | 0.91‐1.92 | 0.66 (3), 0.88 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 6 | 1.45 | 1.14‐1.82 | 35 | 0‐73 | 0.80 | 1.45 | 1.10‐1.89 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 4 | 1.18 | 0.70‐1.96 | 54 | 0‐83 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.72‐1.64 | |

| Moderate depression | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 11 | 1.14 | 0.99‐1.30 | 0 | 0‐51 | 0.30 | 1.19 | 1.05‐1.37 | 0.48(30), 0.92 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 18 | 1.28 | 1.10‐1.47 | 34 | 0‐62 | 0.03 | 1.23 | 1.09‐1.41 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 32 | 1.02 | 0.93‐1.12 | 23 | 0‐50 | 0.35 | 1.03 | 0.94‐1.14 | |

| Mild depression | |||||||||

| Combined vs. psychotherapy | 1 | 1.39 | 0.65‐2.94 | 0 | NA | NA | 0.97 | 0.52‐1.82 | 0.89(1), 0.35 |

| Combined vs. pharmacotherapy | 1 | 0.85 | 0.56‐1.30 | 0 | NA | NA | 1.04 | 0.57‐1.89 | |

| Psychotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy | 5 | 1.14 | 0.77‐1.69 | 52 | 0‐81 | 0.79 | 1.08 | 0.75‐1.54 | |

RR – relative risk, NA – not available

Significant results are highlighted in bold prints

In the meta‐regression analysis including the studies that reported the baseline severity of depression on the HAM‐D, this severity was not associated with response rate in the combined treatment versus psychotherapy comparison (coefficient=–0.2, SE=0.02, p=0.29) or in the combined versus pharmacotherapy comparison (coefficient=–0.02, SE=0.2, p=0.13).

We also conducted separate network meta‐analyses for mild, moderate and severe depression (Table 5). In severe depression, combined treatment was more effective than pharmacotherapy alone (RR=1.45, 95% CI: 1.10‐1.89), while there were only two comparisons of combined treatment with psychotherapy alone. In moderate depression, combined treatment was more effective than either psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone (RR=1.19, 95% CI: 1.05‐1.37, and RR=1.23, 95% CI: 1.09‐1.41), and there was no significant difference between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (RR=1.03, 95% CI: 0.94‐1.14). Unfortunately, there were too few studies in patients with mild depression.

In the multivariate meta‐regression analysis conducted to examine possible sources of heterogeneity, with response as outcome and with the three main nodes (combined treatment, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy), only one predictor was found to be significant (“other” pharmacotherapy versus SSRI: coefficient=–0.55, SE=0.22, p=0.01).

Long‐term effects

We calculated response rates for studies reporting follow‐up outcomes at 6 to 12 months. The pairwise meta‐analyses indicated that combined treatment was more effective than pharmacotherapy at 6 to 12 months follow‐up (RR=0.71, 95% CI: 0.60‐0.84). The other two comparisons did not indicate a significant difference. The network meta‐analysis, however, indicated that combined treatment was not only more effective than pharmacotherapy (RR=0.72, 95% CI: 0.62‐0.83) but also than psychotherapy (RR=0.84, 95% CI: 0.71‐0.99), and that psychotherapy was more effective than pharmacotherapy (RR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.74‐0.98).

The design‐by‐treatment interaction model did not indicate global inconsistency in the network (X2=0.12, df=3, p for the null hypothesis of consistency in the network: 0.99). Because the time to follow‐up varied between 6 and 12 months, we conducted a meta‐regression analysis to examine whether time to follow‐up was associated with the outcome, but this association was not found (all p values >0.32).

DISCUSSION

In this network meta‐analysis, we assessed comparative data from 101 randomized trials and found that combination treatment was more effective than psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone in the treatment of adult depression, and that there were no significant differences between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

We also found that acceptability, defined on the basis of study drop‐out for any reason, was higher in combined treatment than in pharmacotherapy alone, and in psychotherapy than in pharmacotherapy. Acceptability of antidepressants may be lower due to side effects or because many patients prefer psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy134. Combined treatment may therefore be the best option for the treatment of depression both in terms of efficacy and acceptability and, from the perspective of acceptability, pharmacotherapy alone may be not optimal.

The majority of studies were aimed at patient populations with moderate depression. However, this must be considered with caution. We used the average depression scores per study, meaning that within each study the severity of depression could still range from mild to severe. In the relatively few studies on severe depression, we also found that combined treatment was more effective than pharmacotherapy. Unfortunately, only two studies examined combined treatment versus psychotherapy alone among patients with severe depression, so we cannot be certain whether combined treatment is superior for these people. Individual patient data meta‐analyses have suggested that baseline depression severity does not moderate the efficacy of CBT versus antidepressant treatment135, or CBT over pill placebo136. This supports the notion that combined treatment should be the first option for moderate and probably also severe depression. Unfortunately, there were too few studies in patients with mild depressive disorders to say anything about the relative effects of combined treatment, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

There is evidence suggesting that a significant proportion of patients with depression receive psychotropic medication without psychotherapy137, 138. The results of our meta‐analysis suggests that this is probably not the optimal option in terms of quality of care. Although the effects of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are comparable and individual patients may have different clinical situations and specific preferences, psychotherapy is on average more acceptable than pharmacotherapy alone. Findings from this paper clearly show that combined treatment is the best option in moderate depression, and in routine clinical care it would be better to consider psychotherapy as the first choice when only one treatment is offered to a patient. The National Health Service in the UK and other health care systems in the world, including low and middle income countries139, should model themselves accordingly and invest more resources in non‐pharmacological interventions for depression.

In real‐world settings, pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are typically provided by different clinicians and sometimes even at different clinics, with antidepressant medication often being prescribed in primary care and psychotherapy delivered in secondary care or settings outside of the hospital. Moreover, funding of services varies across countries, with different structures for medication and psychotherapy. This may complicate the use of combined treatments. From this perspective, collaborative care offers good opportunities for the dissemination of combined treatments140.

In the majority of trials included in this meta‐analysis, psychotherapy was delivered in an individual format. Only a limited number of trials examined group psychotherapies, and none of the trials used guided self‐help or Internet‐based psychotherapies. It is known from other research that psychotherapies can effectively be delivered in several different formats, including in groups, by telephone, through guided self‐help, and via the Internet141, 142. There are no indications that treatment format is associated with different effects of psychotherapy, as long as at least some personal support is given by a professional. It would be useful to further explore such different therapy formats in combined treatment, because these formats require less resources and are often easier to implement than intensive individual therapies. This could potentially facilitate the use of combined treatments in routine care.

We also found that combined treatment was superior to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy alone in chronic or treatment‐resistant depression. That should be considered with caution, because we pooled all studies of chronic and treatment‐resistant depression into one group, and may have missed specific outcomes for the two conditions. However, this finding is important from a clinical perspective and suggests that combined treatment should be preferred also in this problematic group.

It should be noted that there was some variability among the included studies in terms of the quality of pharmacotherapy administered, the quality of psychotherapy delivered and/or the quality of the study design and conduct. However, all sensitivity analyses limiting to trials of optimized pharmacotherapy, optimized psychotherapy or at low risk of bias produced very similar results. We therefore believe that our conclusions about the relative values of the three treatments are robust.

Unfortunately, the long‐term effects of the treatments are still unknown. We calculated response rates for studies reporting follow‐up outcomes at 6 months or longer. The only three studies reporting outcome data at more than 12 months were excluded from the analyses. The remaining studies were still heterogeneous in terms of continuation of treatment: in most studies no psychotherapy was given during follow‐up, whereas pharmacotherapy was continued during the whole follow‐up period in some studies, and tapered at some point during follow‐up in some others. Other studies were completely naturalistic. We did find indications that, at 6 to 12 months after treatment start, combined treatment is more effective than psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone, and that psychotherapy is more effective than pharmacotherapy. However, these findings should be regarded as preliminary, because the studies varied widely in terms of what happened during follow‐up. The finding that psychotherapy may be more effective than pharmacotherapy in the longer term is in line with previous meta‐analytic research143, and it has also been established previously that combined treatment may be more effective than pharmacotherapy alone14. The results of the analyses should, however, be considered with caution. Further research is clearly very much needed on the long‐term effects of treatments for depression.

Very few studies have compared the effects of combined treatment with placebo. That is unfortunate, because a comparison with placebo would allow to better estimate the actual effects of combined treatment. Previous meta‐analytic research suggested that the effects of combined treatment in depression and anxiety are the sum of the effects of psychotherapy and those of pharmacotherapy11. These findings were very preliminary, because of the broad CIs around the effect sizes found. However, they do suggest that the effects of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may be independent of each other, and can be applied separately. Unfortunately, the present meta‐analysis did not find enough studies to confirm or falsify this finding.

We also found only a limited number of studies comparing the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy with the combination of psychotherapy and placebo. This comparison allows to examine the contribution of medication to the effects of combined treatment. A previous pairwise meta‐analysis suggested that the medication contributed to the effects of combined treatment with a small effect size144. On the other hand, a comparison of psychotherapy plus placebo with psychotherapy alone would allow to estimate the impact of psychotherapy in addition to placebo effects.

This study has several strengths, but also some limitations. The number of trials was too small in specific subsamples, for example in severe or mild depression. Moreover, the majority of trials had at least one domain at high risk of bias. Finally, previous research has indicated that there may be some differences in efficacy and acceptability among specific types of medications6. In our network meta‐analysis, we merged all antidepressants in one node, as we did not have enough studies across different medications to examine that in sufficient detail.

In conclusion, combined treatment is more effective than psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone in the short‐term treatment of moderate depression, and there are no significant differences between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. This is also true in chronic and treatment‐resistant depression, and probably also in severe depression. Acceptability is significantly better in combined treatment and psychotherapy, compared with pharmacotherapy. These findings suggest that guidelines should recommend combined treatment as the first option in the treatment of depression and, because of the higher acceptability, may recommend psychotherapy before pharmacotherapy, depending on the preferences of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was partially funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre, grant BRC‐1215‐20005 (to A. Cipriani). A. Cipriani is also supported by the NIHR Oxford Cognitive Health Clinical Research Facility and by an NIHR Research Professorship (grant RP‐2017‐08‐ST2‐006). The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jorm AF, Patten SB, Brugha TS et al. Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 2017;16:90‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GBD 2016. Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990‐2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211‐59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Docherty M, Shaw K, Goulding L et al. Evidence‐based guideline implementation in low and middle income countries: lessons for mental health care. Int J Ment Health Syst 2017;11:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cipriani A, Tomlinson A. Providing the most appropriate care to our individual patients. Evid Based Ment Health 2019;22:1‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M et al. Who benefits from psychotherapies for adult depression? A meta‐analytic update of the evidence. Cogn Behav Ther 2018;47:91‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Lancet 2018;391:1357‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for depressed patients: a network meta‐analysis. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G et al. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta‐analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:909‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Andersson G et al. The effects of blinding on the outcomes of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression: a meta‐analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2015;30:685‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cristea IA, Gentili C, Pietrini P et al. Sponsorship bias in the comparative efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression: a meta‐analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:16‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL et al. Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry 2014;13:56‐67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ijaz S, Davies P, Williams CJ et al. Psychological therapies for treatment‐resistant depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;5:CD010558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tolin DF. Can cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression be improved with pharmacotherapy? A meta‐analysis. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017;40:715‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karyotaki E, Smit Y, Holdt Henningsen K et al. Combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy or monotherapy for major depression? A meta‐analysis on the long‐term effects. J Affect Disord 2016;194:144‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL et al. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta‐analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 2013;12:137‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mavridis D, Giannatsi M, Cipriani A et al. A primer on network meta‐analysis with emphasis on mental health. Evid Based Ment Health 2015;18:40‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E. A meta‐analytic database of randomised trials on psychotherapies for depression. https://osf.io/825c6/. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell LF, Norcross JC, Vasquez MJ et al. Recognition of psychotherapy effectiveness: the APA resolution. Psychotherapy 2013;50:98‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5. 10 http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:7‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Bohlmeijer E et al. The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta‐analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol Med 2010;40:211‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Barbui C et al. Imputing response rates from means and standard deviations in meta‐analyses. Psychopharmacology 2005;20:49‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orsini N, Bottai M, Higgins J et al. Heterogi: Stata module to quantify heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s449201.html. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hutton B, Wolfe D, Moher D et al. Reporting guidance considerations from a statistical perspective: overview of tools to enhance the rigour of reporting of randomised trials and systematic reviews. Evid Based Ment Health 2017;20:46‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE et al. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Meth Med Res 2008;17:279‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salanti G. Indirect and mixed‐treatment comparison, network, or multiple‐treatments meta‐analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Meth 2012;3:80‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chaimani A, Higgins JP, Mavridis D et al. Graphical tools for network meta‐analysis in STATA. PLoS One 2013;8:e76654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Higgins JPT, Jackson D, Barrett JK et al. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta‐analysis: concepts and models for multi‐arm studies. Res Synth Meth 2012;3:98‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D et al. Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord 2013;150:384‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmadpanah M, Nazaribadie M, Aghaei E et al. Influence of adjuvant detached mindfulness and stress management training compared to pharmacologic treatment in primiparae with postpartum depression. J Health Psychol 2016;21:1216‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altamura M, Iuso S, Terrone G et al. Comparing interpersonal counseling and antidepressant treatment in primary care patients with anxious and nonanxious major depression disorder: a randomized control trial. Clin Neuropsychiatr 2017;14:257‐62. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A et al. A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive‐behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ 1997;314:932‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ashouri A, Atef‐Vahid MK, Gharaee B et al. Effectiveness of meta‐cognitive and cognitive‐behavioral therapy in patients with major depressive disorder. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci 2013;7:24‐34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barber JP, Barrett MS, Gallop R et al. Short‐term dynamic psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:66‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barrett JE, Williams JW Jr, Oxman TE et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized trial in patients aged 18 to 59 years. J Fam Pract 2001;50:405‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beck AT, Hollon SD, Young JE et al. Treatment of depression with cognitive therapy and amitriptyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985;42:142‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bedi N, Chilvers C, Churchill R et al. Assessing effectiveness of treatment of depression in primary care. Partially randomised preference trial. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:312‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bellack AS, Hersen M, Himmelhoch J. Social skills training compared with pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:1562‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bellino S, Zizza M, Rinaldi C et al. Combined therapy of major depression with concomitant borderline personality disorder: comparison of interpersonal and cognitive psychotherapy. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:718‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blackburn IM, Bishop S, Glen AIM. The efficacy of cognitive therapy in depression: a treatment trial using cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy, each alone and in combination. Br J Psychiatry 1981;139:181‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blackburn IM, Moore RG. Controlled acute and follow‐up trial of cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy in out‐patients with recurrent depression. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:328‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bloch M, Meiboom H, Lorberblatt M et al. The effect of sertraline add‐on to brief dynamic psychotherapy for the treatment of postpartum depression: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:235‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blom K, Jernelöv S, Kraepelien M et al. Internet treatment addressing either insomnia or depression, for patients with both diagnoses: a randomized trial. Sleep 2015;38:267‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Browne G, Steiner M, Roberts J et al. Sertraline and/or interpersonal psychotherapy for patients with dysthymic disorder in primary care: 6‐month comparison with longitudinal 2‐year follow‐up of effectiveness and costs. J Affect Disord 2002;68:317‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Burnand Y, Andreoli A, Kolatte E et al. Psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine in the treatment of major depression. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53:585‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chibanda D, Shetty AK, Tshimanga M et al. Group problem‐solving therapy for postnatal depression among HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative mothers in Zimbabwe. J Int Assoc Prov AIDS Care 2014;13:335‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Corruble E, Swartz HA, Bottai T et al. Telephone‐administered psychotherapy in combination with antidepressant medication for the acute treatment of major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2016;190:6‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Covi L, Lipman RS. Cognitive behavioral group psychotherapy combined with imipramine in major depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987;23:173‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. David D, Szentagotai A, Lupu V et al. Rational emotive behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial, posttreatment outcomes, and six‐month follow‐up. J Clin Psychol 2008;64:728‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. de Jonghe F, Kool S, van Aalst G et al. Combining psychotherapy and antidepressants in the treatment of depression. J Affect Disord 2001;64:217‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. de Jonghe F, Hendricksen M, van Aalst G et al. Psychotherapy alone and combined with pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:37‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Mello MF, Myczcowisk LM, Menezes PR. A randomized controlled trial comparing moclobemide and moclobemide plus interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. J Psychother Pract Res 2001;10:117‐23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dekker JJ, Koelen JA, Van HL et al. Speed of action: the relative efficacy of short psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the first 8 weeks of a treatment algorithm for depression. J Affect Disord 2008;109:183‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Denton WH, Wittenborn AK, Golden RN. Augmenting antidepressant medication treatment of depressed women with emotionally focused therapy for couples: a randomized pilot study. J Mar Fam Ther 2012;38(Suppl.1):23‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:409‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:658‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dozois DJA, Bieling PJ, Evraire LE et al. Changes in core beliefs (early maladaptive schemas) and self‐representation in cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Int J Cogn Ther 2014;7:217‐34. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Mletzko TC et al. Depression beliefs, treatment preference, and outcomes in a randomized trial for major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:375‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Aponte‐Rivera V et al. Effects of patient preferences on outcomes in the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) study. Am J Psychiatry 2017;174:546‐56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dunn RJ. Cognitive modification with depression‐prone psychiatric patients. Cogn Ther Res 1979;3:307‐17. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dunner DL, Schmaling KB, Hendrickson H et al. Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. Depression 1996;4:34‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Eisendrath SJ, Gillung E, Delucchi KL et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for treatment‐resistant depression. Psychother Psychosom 2016;85:99‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:971‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Faramarzi M, Alipor A, Esmaelzadeh S et al. Treatment of depression and anxiety in infertile women: cognitive behavioral therapy versus fluoxetine. J Affect Disord 2008;108:159‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Finkenzeller W, Zobel I, Rietz S et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for post‐stroke depression. Feasibility and effectiveness. Nervenarzt 2009;80:805‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Frank E, Cassano GB, Rucci P et al. Predictors and moderators of time to remission of major depression with interpersonal psychotherapy and SSRI pharmacotherapy. Psychol Med 2011;41:151‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gater R, Waheed W, Husain N et al. Social intervention for British Pakistani women with depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:227‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gaudiano BA, Busch AM, Wenze SJ et al. Acceptance‐based behavior therapy for depression with psychosis: results from a pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Pract 2015;21:320‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hautzinger M, De Jong‐Meyer R, Treiber R et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy, pharmacotherapy, and the combination of both in non‐melancholic, unipolar depression. Zeitschr Klin Psychol 1996;25:130‐45. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hegerl U, Hautzinger M, Mergl R et al. Effects of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in depressed primary‐care patients: a randomized, controlled trial including a patients' choice arm. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010;13:31‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hellerstein DJ, Little SA, Samstag LW et al. Adding group psychotherapy to medication treatment in dysthymia: a randomized prospective pilot study. J Psychother Pract Res 2001;10:93‐103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Evans MD et al. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Singly and in combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:774‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Fawcett J et al. Effect of cognitive therapy with antidepressant medications vs antidepressants alone on the rate of recovery in major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:1157‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77. Hsiao FH, Jow GM, Lai YM et al. The long‐term effects of psychotherapy added to pharmacotherapy on morning to evening diurnal cortisol patterns in outpatients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom 2011;80:166‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Husain N, Zulqernain F, Carter LA et al. Treatment of maternal depression in urban slums of Karachi, Pakistan: a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an integrated maternal psychological and early child development intervention. Asian J Psychiatry 2017;29:63‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D et al. Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:431‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral‐analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1462‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kennedy SH, Konarski JZ, Segal ZV et al. Differences in brain glucose metabolism between responders to CBT and venlafaxine in a 16‐week randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:778‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lam RW, Parikh SV, Ramasubbu R et al. Effects of combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for improving work functioning in major depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2013;203:358‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lesperance F, Frasure‐Smith N, Koszycki D et al. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. JAMA 2007;297:367‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lynch TR, Morse JQ, Mendelson T et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: a randomized pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:33‐45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Macaskill ND, Macaskill A. Rational‐emotive therapy plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy alone in the treatment of high cognitive dysfunction depression. Cogn Ther Res 1996;20:575‐92. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Maina G, Rosso G, Rigardetto S et al. No effect of adding brief dynamic therapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of obsessive‐compulsive disorder with concurrent major depression. Psychother Psychosom 2010;79:295‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Maldonado López A. Terapia de conducta y depresión: un análisis experimental de los modelos conductual y cognitivo. Rev Psicolog Gen Aplic 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Maldonado López A. Un modelo de terapia cognitiva desde la perspectiva de la psicología del aprendizaje. Anuar Psicolog 1984;30:75‐96. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Markowitz JC, Kocsis JH, Fishman B et al. Treatment of depressive symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus‐positive patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:452‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Markowitz JC, Kocsis JH, Bleiberg KL et al. A comparative trial of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for “pure” dysthymic patients. J Affect Disord 2005;89:167‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Marshall MB, Zuroff DC, McBride C et al. Self‐criticism predicts differential response to treatment for major depression. J Clin Psychol 2008;64:231‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Martin SD, Martin E, Rai SS et al. Brain blood flow changes in depressed patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy or venlafaxine hydrochloride: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:641‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. McKnight DL, Nelson‐Gray RO, Barnhill J. Dexamethasone suppression test and response to cognitive therapy and antidepressant medication. Behav Ther 1992;23:99‐111. [Google Scholar]

- 94. McLean PD, Hakstian AR. Clinical depression: comparative efficacy of outpatient treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979;47:818‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Menchetti M, Rucci P, Bortolotti B et al. Moderators of remission with interpersonal counselling or drug treatment in primary care patients with depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2014;204:144‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Ericksen J et al. Treatment of postnatal depression with cognitive behavioural therapy, sertraline and combination therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:236‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL et al. Treating depression in predominantly low‐income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:57‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Misri S, Reebye P, Corral M et al. The use of paroxetine and cognitive‐behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1236‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mitchell PH, Veith RC, Becker KJ et al. Brief psychosocial‐behavioral intervention with antidepressant reduces poststroke depression significantly more than usual care with antidepressant living well with stroke: randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2009;40:3073‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE et al. Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive‐behavior therapy, supportive‐expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69:942‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Moradveisi L, Huibers MJ, Renner F et al. Behavioural activation v. antidepressant medication for treating depression in Iran: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:204‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Murphy GE, Simons AD, Wetzel RD et al. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy. Singly and together in the treatment of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984;41:33‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Murphy GE, Carney RM, Knesevich MA et al. Cognitive behavior therapy, relaxation training, and tricyclic antidepressant medication in the treatment of depression. Psychol Rep 1995;77:403‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mynors‐Wallis L, Gath D, Lloyd‐Thomas A et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ 1995;310:441‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]