Abstract

Macrobrachium (Bate, 1868) is a large and cosmopolitan crustacean genus of high economic importance worldwide. We investigated the morphological and molecular identification of freshwater prawns of the genus Macrobrachium in South, South West, and Littoral regions of Cameroon. A total of 1,566 specimens were examined morphologically using a key described by Konan (Diversité morphologique et génétique des crevettes des genres Atya Leach, 1816 et Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 de Côte d'Ivoire, 2009, Université d'Abobo Adjamé, Côte d'Ivoire), leading to the identification of seven species of Macrobrachium: M. vollenhovenii (Herklots, 1857); M. macrobrachion (Herklots, 1851); M. sollaudii (De Man, 1912); M. dux (Lenz, 1910); M. chevalieri (Roux, 1935); M. felicinum (Holthuis, 1949); and an undescribed Macrobrachium species M. sp. To validate the genetic basis of the identified species, 94 individuals representing the species were selected and subjected to genetic characterization using 1,814 DArT markers. The admixture analysis revealed four groups: M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion; M. chevalieri; M. felicinum and M. sp; and M. dux and M. sollaudii. But, the principal component analysis (PCA) separated M. sp and M. felicinum to create additional group (i.e., five groups). Based on these findings, M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion may be conspecific, as well as M. dux and M. sollaudii, while M. felicinum and M. sp seems to be different species, suggesting a potential conflict between the morphological identification key and the genetic basis underlying speciation and species allocation for Macrobrachium. These results are valuable in informing breeding design and genetic resource conservation programs for Macrobrachium in Africa.

Keywords: Cameroon, DArT markers, freshwater prawn, Konan key, Macrobrachium, morphological and molecular characterization

Macrobrachium is a large crustacean genus of high economic importance. Morphological characterization and molecular characterization of prawns of this genus were undertaken in the three regions of the coastal area Cameroon. Seven species were identified morphologically: M. vollenhovenii; M. macrobrachion; M. sollaudii; M. dux; M. chevalieri; M. felicinum; and an undescribed Macrobrachium species M. sp, while genetic structure using 1,814 DArT markers showed close similarity between M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion, and M. dux and M. sollaudii.

1. INTRODUCTION

The freshwater prawns of genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea, Decapoda, and Palaemonidea) constitute one of the most diverse, abundant, and widespread crustacean genera (Murphy & Austin, 2005). The species of this genus are distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical zones of the world (Fossati, Mosseron, & Keith, 2002; Holthuis, 1980; March, Pringle, Townsend, & Wilson, 2002). Various studies have identified approximately 240 species of Macrobrachium (Chen, Tsai, & Tzeng, 2009; De Grave & Fransen, 2011; Holthuis & Ng, 2010; Wowor et al., 2009). Although the majority of Macrobrachium species inhabit freshwaters, some are entirely restricted to estuaries and many require brackish water during larval development (New, 2002).

In West Africa, Macrobrachium species can be found throughout the region and play an important role in domestic fishery resources (Etim & Sankare, 1998; Nwosu & Wolfi, 2006). They are commercially important and sustain viable artisanal fisheries in some rivers and estuaries within the region, while also providing direct and secondary employment (Marioghae, 1990; Okogwu, Ajuogu, & Nwani, 2010). However, the species are poorly known in the region. Monod (1980) developed a Macrobrachium characterization key, which when applied to West Africa resulted in the identification of 10 species of Macrobrachium: M. vollenhovenii (Herklots, 1857), M. macrobrachion (Herklots, 1851), M. chevalieri (Roux, 1935), M. dux (Lenz, 1910), M. felicinum (Holthuis, 1949), M. raridens (Hilgendorf, 1893), M. thysi (Powell, 1980), M. equidens (Dana, 1852), M. zariquieyi (Holthius, 1949), and M. sollaudii (De Man, 1912), of which four are found in Cameroon: M. vollenhovenii, M. macrobrachion, M. chevalieri, and M. sollaudii (Monod, 1966, 1980; Powell, 1980). However, Monod (1980) cautioned that the use of his key is limited to adult males only.

Taking into consideration both sex and size of the prawn, Konan (2009) developed a new key for identification of West Africa Macrobrachium. Using the newly developed key, Makombu et al. (2015) described a tentative range of the biodiversity of Macrobrachium in the South region and increased the number of known species in Cameroon from four (Monod, 1980) to six (Makombu et al., 2015). Other studies also pointed out the higher species richness of Cameroon Macrobrachium (Doume, Toguyeni, & Yao, 2013; Tchakonté et al., 2014). However, these recent studies in Cameroon have not covered the whole coastal area, which encompasses three regions namely South, South West, and Littoral regions. With the increasing threat of the quality of fresh and brackish water of the coastal area of Cameroon (E & D, 2009; Folack, 1995) that can affect species integrity, information on the genetic diversity of Macrobrachium in the whole coastal region is urgently needed to implement a management plan.

Application of species identification keys relies heavily on distinct morphological features unique to each species. However, due to a restricted number of characters available for identification, with many features common to all known species of Macrobrachium, morphological identification of species of this genus is quite difficult (Qing‐Yi, Qi‐qun, & Wei‐bing, 2009). Characterization based only on morphological examination could lead to under‐ or overestimation of biodiversity (Lefébure, Douady, Gouy, & Gilbert, 2006). Given the current scenario, unbiased taxonomic classification through both morphological characterization and molecular characterization could shed more light into the diversity of this genus in the region.

Several studies have used mitochondrial DNA sequence data from the 16S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) genes to characterize Asian Macrobrachium taxonomy, biogeography, evolution, and life history (Liu, Cai, & Tzeng, 2007; Murphy & Austin, 2003, 2005; Pileggi & Mantelatto, 2010; Qing‐Yi et al., 2009; Vergamini, Pileggi, & Mantelatto, 2011). Microsatellites have also been developed for Macrobrachium rosenbergii De Man, 1879 (Divu, Khushiramani, Malathi, Karunasagar, & Karunasagar, 2008). The emergence of next‐generation sequencing tools has revolutionized taxonomic classification studies, as cost per sequencing output is continuously decreasing (Kilian et al., 2012). This has resulted in a shift of focus from molecular identification studies using universal genetic markers to high‐throughput genotyping using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). One of the emerging new genotyping technologies is Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) (Imelfort, Batley, Grimmond, & Edwards, 2009; Kilian et al., 2012), which allows for simultaneous detection of several thousand of DNA polymorphisms (depending on the species) by scoring the presence or absence of DNA fragments in genomic representations generated from genomic DNA through a process of complexity reduction (Kilian et al., 2012). The efficacy of DArT markers in the analysis of genetic diversity, population structure, association mapping, and construction of linkage maps has been demonstrated for a variety of species (Appleby, Edwards, & Batley, 2009). DArT does not rely on previous sequence information for initial marker development, and this makes it the chosen platform for genetic characterization of species with little sequence information like African Macrobrachium (Sánchez‐Sevilla et al., 2015).

This study sought to determine the morphological and genetic diversity of Macrobrachium species in the main rivers of the South, South West, and Littoral regions of Cameroon using Konan (2009) key and DArT technology. It will serve to validate the current morphological‐based classification of West Africa Macrobrachium and contribute to the design of Macrobrachium breeding in Africa.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethics statement

In Cameroon, freshwater prawn fishing is artisanal and an authorized activity. We bought fresh specimens from fishermen who chill and market wild prawn immediately after capture.

2.2. Sampling and collection of biological materials

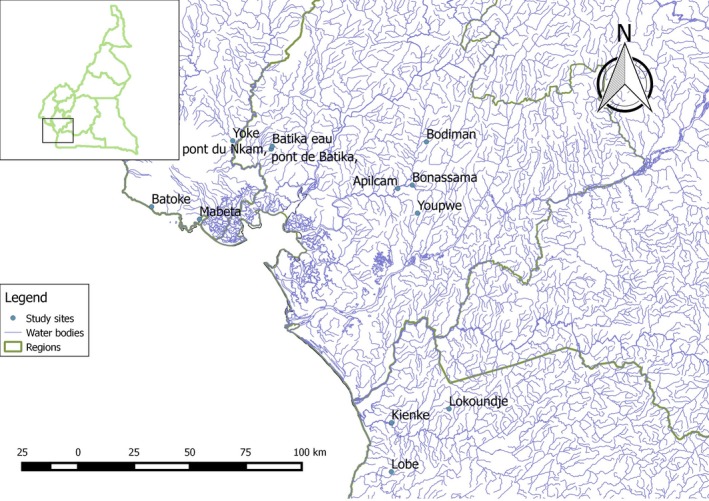

Between May 2015 and April 2016, Macrobrachium samples were collected monthly from fishermen catches at Lokoundje, Kienke, and Lobe rivers, in the South region; at Batoke, Mabeta, and Yoke rivers in the South West region; and at Nkam and Wouri rivers in the Littoral region, Cameroon. Coordinates of each collection point were taken using GPS (Figure 1). Samples were transported to the laboratory of the Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD) Batoke, Limbe, for measurements and taxonomic examinations.

Figure 1.

Map of the Atlantic Coast of Cameroon, showing the study sites

2.3. Morphological identification of prawns

Before measurements, specimens were weighed individually using an electronic balance, coded, and preserved in 95% ethanol. Morphometric variables were recorded according to the measurement technique described by Kuris, Ra'anan, Sagi, and Cohen (1987) for the separation of morphotype of M. rosenbergii. Measurements of all characters were made to the nearest 0.01 mm using dial calipers type Stainless Hardened (range 0–200 mm) for the measurement of large specimens, and with magnifying binocular glasses for small specimens. All dimensions of the two legs of the second pair of the pereiopods and their joints were taken along the external lateral line. For each of the specimens collected, a total of 33 morphometric and six meristic characters were recorded (Appendix 1). After measurement, the specimens were identified to species level using the key described by Konan (2009) (Appendix 2). The Monod (1980) key was used when the species description was not found in Konan key. Samples were then stored in 95% ethanol for further molecular analysis.

2.4. Measurements of physicochemical parameters

Measurements of water physicochemical parameters of the rivers were done according to APHA (1998) and Rodier, Legube, and Brunet (2009) standards to see whether they have an influence in the distribution of Macrobrachium species in the three regions. Water temperature and dissolved oxygen were monitored monthly using oxygen meter (HI 9146, Hanna, Italy), while pH was measured using a pH meter (HI 98129, Hanna, USA).

2.5. Morphometric analysis

The Hierarchical Ascending Classification (AHC) based on Euclidean distance and Ward's algorithm was carried out to cluster species identified according to their morphometric similarities.

2.6. DNA extraction and genotyping

Due to financial limitations, a smaller set of 94 samples out of 1,566 collected (Appendix 3) was selected for molecular analysis. These samples were selected purposely (a) to represent all the species identified in the morphological analysis and (b) be a representative of sampled rivers and regions in order to assess potential genetic substructure among regions. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the muscle tissue of a pleopod using the DNeasy Blood/Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, 30 µl of 50–100 ng/µl for each sample was sent to Diversity Arrays Technology Pty Ltd. (DArT P/L) (http://www.diversityarrays.com/dart-mapsequences), for genotyping using a Genotyping‐by‐sequencing (GBS) approach as described by Elshire et al. (2011) using 52,834 DArT markers.

A total of 93 samples were successfully genotyped comprising 18 samples from M. dux; 18, M. macrobrachion; 18, M. sollaudii; 17, M. vollenhovenii; 12, M. chevalieri; 5, M. felicinum; and 5, M. sp.

2.7. Data filtering

Genotypic data quality control and checks were undertaken using PLINK v 1.9 (Purcell et al., 2007) entailing removal of SNPs with <80% call rate and <5% minor allele frequency (MAF). Consequently, a total of 1,814 SNPs were remained for further analysis.

2.8. Genetic diversity

Minor allele frequencies (MAF) were estimated using PLINK v 1.9 (Purcell et al., 2007). The distribution of MAF in each species was represented as the proportion of all the SNPs used in the analysis and subsequently grouped into five classes: [0.0,0.1], [0.1,0.2], [0.2,0.3], [0.3,0.4], and [0.4,0.5]. The proportions of SNPs in each class were then graphed for comparison between species using R (R Core Team, 2017).

Observed and expected heterozygosities were calculated using ARLEQUIN software, version 3.5 (Excoffier & Lischer, 2010). The expected heterozygosity per locus was calculated as follows:

where n is the number of gene copies in the sample, k is the number of haplotypes, and pi is the sample frequency of the ith haplotype.

2.9. Population structure

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using PLINK (Purcell et al., 2007) and results were visualized using the GENESIS package (Buchmann & Hazelhurst, 2015) in R v 3.4.4.

A model‐based unsupervised clustering method implemented in the program ADMIXTURE v. 1.3.0 (Alexander, Novembre, & Lange, 2009) was used to estimate the genetic composition of individual prawns using the 1,814 markers. The analysis was run with K (number of distinct species) independent runs ranging from 2 to 20. A 10‐fold cross‐validation (CV = 10) was specified, with the resultant error profile used to explore the most probable number of clusters (K), as described by Alexander et al. (2009). The optimal K was confirmed using discriminate principal component analysis (DPCA) and the Evanno ΔK methods. Graphical display of the admixture analysis was done using the Microsoft Excel package.

2.10. Analysis of genetic relationships

Pairwise F ST was computed with 1,000 permutations using ARLEQUIN software, version 3.5 (Excoffier & Lischer, 2010). A phylogenetic tree was then generated from a matrix of pairwise F ST estimates using Splits Tree software, version 4.13.1 (Huson & Bryant, 2006).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Physicochemical parameters of the rivers

The physicochemical parameters of the eight rivers sampled are shown in Table 1. The mean pH of all the rivers was between 7.08 and 7.70. Temperature varied from 23.66 to 29.28°C. Lokoundje River recorded the highest mean temperature (26.64°C). Dissolved oxygen was highly variable in the rivers of the Littoral region (Nkam River: 2–8 mg/L), whereas in the South West region, it was high in all the rivers with the lowest value recorded in Batoke River (5–6.63 mg/L).

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters measured in eight rivers of the coastal area of Cameroon

| Regions | Rivers | T (°C) | DO (mg/L) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Littoral | Nkam | |||

| Mean | 25.68 | 6.5 | 7.2 | |

| SD | 0.58 | 1.52 | 0.58 | |

| Range | 24.6–26.8 | 2.0–8.0 | 6.2–8.6 | |

| Wouri | ||||

| Mean | 25.91 | 5.8 | 7.08 | |

| SD | 0.61 | 1.62 | 0.58 | |

| Range | 24.7–27 | 3.5–8.0 | 6.1–8.01 | |

| South | Kienke | |||

| Mean | 25.51 | 4.83 | 7.18 | |

| SD | 1.33 | 0.51 | 0.11 | |

| Range | 23.66–28.32 | 4.1–5.68 | 6.61–7.23 | |

| Lobe | ||||

| Mean | 25.63 | 4.29 | 7.1 | |

| SD | 1.29 | 0.31 | 0.15 | |

| Range | 23.51–28.71 | 4–5.2 | 6.6–7.25 | |

| Lokoundje | ||||

| Mean | 26.64 | 6.42 | 7.31 | |

| SD | 1.49 | 0.71 | 0.17 | |

| Range | 24.6–29.28 | 5.5–7.7 | 6.9–7.7 | |

| South West | Batoke | |||

| Mean | 25.5 | 5.67 | 7.7 | |

| SD | 0.62 | 0.9 | 0.53 | |

| Range | 24.1–26.5 | 5–6.63 | 6.5–8.8 | |

| Mabeta | ||||

| Mean | 24.71 | 6.80 | 7.28 | |

| SD | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.44 | |

| Range | 24.1–26.7 | 5.90–7.99 | 6.1– 8.4 | |

| Yoke | ||||

| Mean | 25.5 | 6.31 | 7.3 | |

| SD | 0.88 | 0.42 | 0.35 | |

| Range | 24.3–27 | 5.91–7.6 | 6.5–8.0 | |

3.2. Morphological analysis and distribution of the species in the three regions

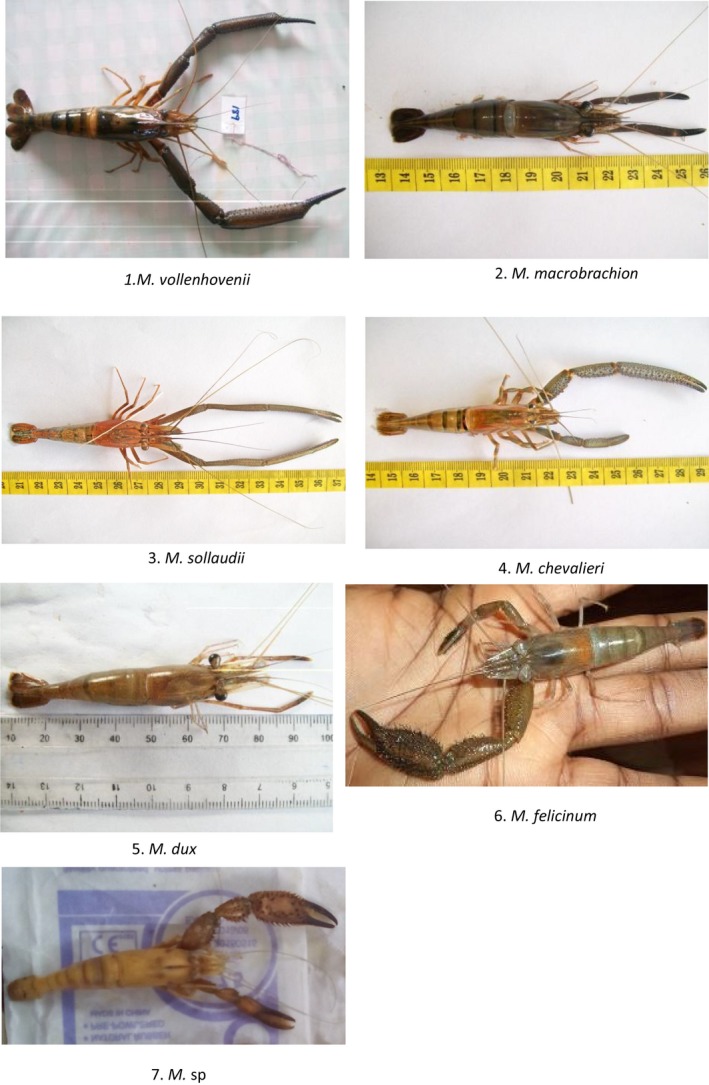

Of the 1,566 specimens examined morphologically using Konan (2009) and Monod (1980) keys (Table 2), 916 (58.5%) were recorded in South region, 398 (25.5%) in South West region, and 252 (16.1%) in Littoral region. Based on the morphometric measures and species allocation criteria described by the keys, seven prawn species were identified. These were M. vollenhovenii, M. macrobrachion, M. sollaudii, M. dux, M. chevalieri, M. felicinum, and an undescribed species, M. sp (Figure 2). These species were not found in all the three regions (Table 3). M. felicinum was found only in the South region, M. sp was found exclusively in the South West region, while M. chevalieri, M. felicinum, and M. sp were absent in the Littoral region.

Table 2.

Species and sample size and sampling regions of Macrobrachium spp. identified using morphological analysis

| Region | Rivers | M. chevalieri | M. dux | M. felicinum | M. macrobrachion | M. sollaudii | M. sp | M. vollenhovenii | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Kienke | 18 | 40 | 8 | 78 | 25 | 90 | 259 | |

| Lobe | 21 | 36 | 4 | 79 | 27 | 124 | 291 | ||

| Lokoundje | 33 | 45 | 28 | 79 | 14 | 167 | 366 | ||

| Littoral | Nkam | 56 | 46 | 102 | |||||

| Wouri | 54 | 20 | 59 | 17 | 150 | ||||

| South West | Batoke | 41 | 23 | 8 | 13 | 79 | 15 | 179 | |

| Mabeta | 10 | 18 | 19 | 27 | 74 | ||||

| Yoke | 5 | 3 | 42 | 2 | 93 | 145 | |||

| Total | 118 | 267 | 40 | 324 | 205 | 79 | 533 | 1,566 |

Figure 2.

Images of the seven species of Macrobrachium identified through morphological analysis in the coastal area of Cameroon. 1: M. vollenhovenii, 2: M. macrobrachion, 3: M. sollaudii, 4: M. chevalieri, 5: M. dux, 6: M. felicinum, 7: M. sp

Table 3.

Distribution of Macrobrachium in the three regions

| Species | Littoral | South | South West |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. vollenhovenii | + | + | + |

| M. macrobrachion | + | + | + |

| M. dux | + | + | + |

| M. sollaudii | + | + | + |

| M. chevalieri | − | + | + |

| M. felicinum | − | + | − |

| M. sp | − | − | + |

Key: + = presence, − = absence.

3.3. Morphometric similarities between species identified

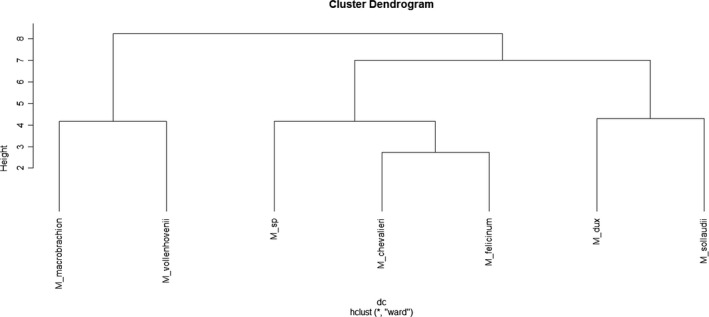

A dendrogram of hierarchical cluster analysis showing morphological similarities between Macrobrachium species is shown in Figure 3. The dendrogram shows the presence of three main branches (i.e., groups of species), the first one groups M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion, the second one groups M. sp, M. chevalieri and M. felicinum with the latter two species being more closely related, and the third branch groups M. dux and M. sollaudii.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram of hierarchical cluster analysis between species of Macrobrachium from coastal area of Cameroon

3.4. Genetic diversity

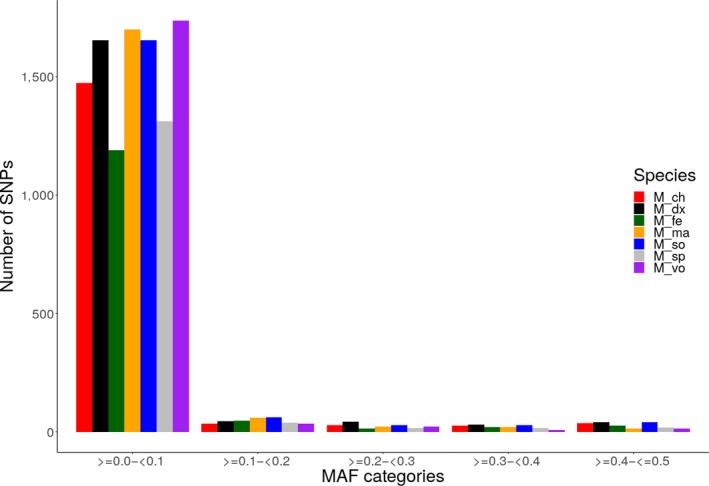

Diversity Arrays Technology markers presented an average genotype call rate of 40.8% and an average scoring reproducibility of 99.9%. The PIC values ranged from 0.02 to 0.50 with an average of 0.15. The heterozygosity estimates and minor allele distribution are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4, respectively. Approximately 85% of all loci had minor allele frequencies <0.1.

Table 4.

Genetic diversity parameters of Macrobrachium from the coastal region of Cameroon. Values are estimates ± SD

| Groups |

Observed Het |

Expected Het |

Monomorphic loci | Polymorphic loci | F IS | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. sp | 0.41 ± 0.32 | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 871 | 61 | −0.34 | .90 |

| M. dux | 0.31 ± 0.27 | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 821 ± 5 | 111 ± 5 | −0.28 | 1 |

| M. macrobrachion | 0.05 ± 0.10 | 0.14 ± 0.09 | 731 ± 187 | 201 ± 187 | 0.61 | .01 |

| M. chevalieri | 0.35 ± 0.29 | 0.31 ± 0.17 | 834 ± 0 | 98 ± 0 | −0.19 | .97 |

| M. sollaudii | 0.27 ± 0.25 | 0.24 ± 0.17 | 822 ± 5 | 110 ± 5 | −0.18 | .99 |

| M. vollenhovenii | 0.15 ± 0.14 | 0.20 ± 0.15 | 858 ± 7 | 74 ± 7 | 0.04 | .20 |

| M. felicinum | 0.45 ± 0.32 | 0.37 ± 0.16 | 858 | 74 | −0.32 | .88 |

Het: heterozygosity; M: Macrobrachium; F IS: inbreeding coefficient

Figure 4.

Minor allele frequency (MAF) distribution for each species. MAF were calculated for each species and SNPs binned into five categories (≥0 to 0.1, ≥0.1 to 0.2, >0.2 to <0.3, ≥0.3 to <0.4, and ≥0.4 to ≤0.5) based on their MAF. M: Macrobrachium, ch: chevalieri; dx: dux; fe: felicinum; ma: macrobrachion; so: sollaudii; vo: vollenhovenii

3.5. Population structure

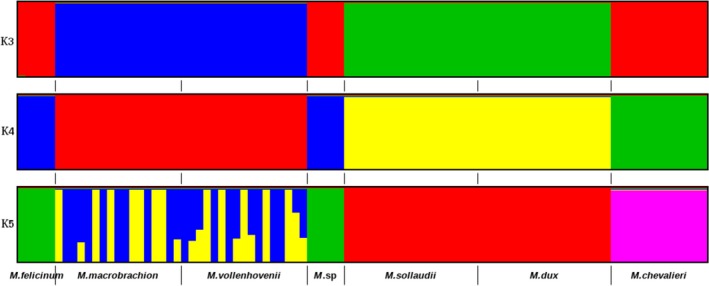

The admixture analysis revealed four main clusters (K = 4) (Figure 5). At K = 3, M. sp, M. chevalieri, and M. felicinum species clustered together as a single group, M. dux and M. sollaudii species clustered as a second group, while M. macrobrachion and M. vollenhovenii clustered as a third group. At K = 4, M. chevalieri formed a distinct group split from group 1. At K = 5, there was no further substructure that emerged. However, individuals in group 3 that consist of M. macrobrachion and M. vollenhovenii revealed substantial admixture derived from two hitherto distinct genetic backgrounds.

Figure 5.

Admixture bar plot showing species proportions at assumed clusters K = 3–5

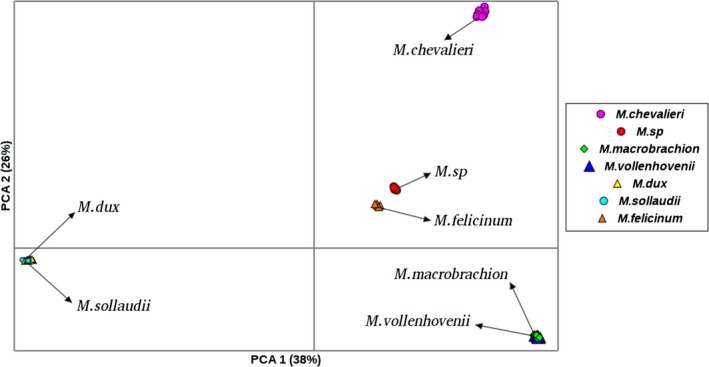

Results from PCA revealed five clusters as shown in Figure 6. The first principal component accounted for 38% of the total variation and separated M. dux and M. sollaudii from the rest of the species. The second component accounted for 26% of the total variation and separated M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion from the other species. M. sp and M. felicinum species formed two distinct groups that were in close proximity, while M. chevalieri formed a distinct cluster.

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of Macrobrachium based on 1,814 DArT markers

3.6. Population differentiation

The genetic distance of the species based on F st ranged from −0.0105 to 0.9461 (Table 5). The lowest genetic distance (F st = −0.0105) was observed between M. dux and M. sollaudii, while the highest differentiation (F st = 0.9461) was obtained between M. sp and M. vollenhovenii.

Table 5.

Pairwise F st among Macrobrachium species

| M. sp | M. dux | M. macro | M. che | M. sol | M. vol | M. fel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. sp | 0 | ||||||

| M. dux | 0.9268 | 0 | |||||

| M. macro | 0.8647 | 0.8889 | 0 | ||||

| M. che | 0.9339 | 0.9280 | 0.8604 | 0 | |||

| M. sol | 0.9265 | −0.0105 | 0.8887 | 0.9279 | 0 | ||

| M. vol | 0.9461 | 0.9360 | 0.0139 | 0.9327 | 0.9360 | 0 | |

| M. fel | 0.9077 | 0.9195 | 0.8549 | 0.9262 | 0.9194 | 0.9402 | 0 |

Abbreviations: che, chevalieri; fel, felicinum; M, Macrobrachium; macro, macrobrachion; sol, sollaudii; vol, vollenhovenii.

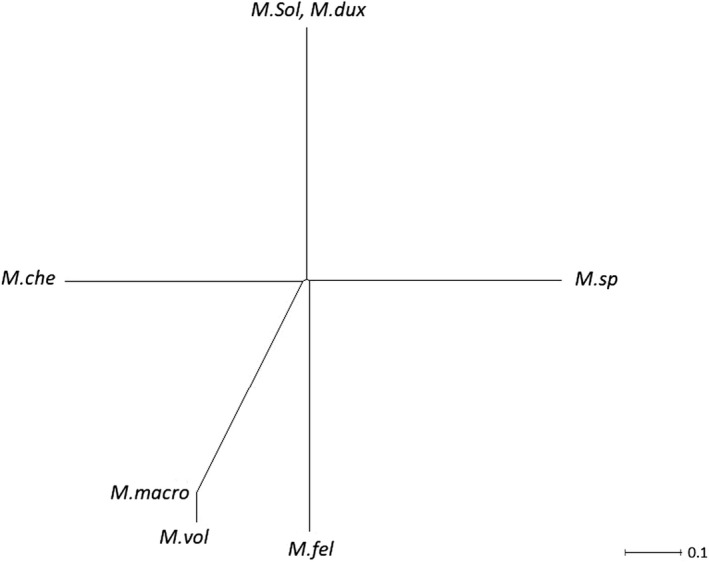

In line with the PCA findings, the phylogenetic tree differentiated M. sp from M. felicinum (Figure 7). More interestingly, M. dux and M. sollaudii appeared at the same node.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of Macrobrachium species detected in the study. che, chevalieri; fel, felicinum; M, Macrobrachium; macro, macrobrachion; sol, sollaudii; vol, vollenhovenii

4. DISCUSSION

Major systematic treatments of freshwater prawns have been based on morphological characteristics alone (Murphy & Austin, 2003; Rossi & Mantelatto, 2013). The complexity of prawns of the genus Macrobrachium where morphological traits have been shown to be strongly influenced by the environment and may not be indicative of underlying genetic divergence (Dimmock, Willamson, & Mather, 2004) has often led to over/underestimation of the diversity (Lefébure et al., 2006). This study sought to use both morphological and genetic approaches in a bid to not only correctly identify the prawn species present in Cameroon, but also contrast the allocation of individual prawns to prospective species using a combined and more reliable analysis.

Based on the morphological key, the samples obtained represent seven distinct species in the coastal area of Cameroon, namely M. vollenhovenii, M. macrobrachion, M. sollaudii, M. dux, M. chevalieri, M. felicinum, and an undescribed species M. sp. This is in contrast with previous studies on known Macrobrachium in Cameroon, where four (Monod, 1980) and six (Makombu et al., 2015) species were identified. The difference in the number of identified species could be explained by the sampling strategy. The Makombu et al. (2015) study was limited to the South region, while the Monod (1980) focused on general investigation of Macrobrachium in West Africa with limited sampling in Cameroon. Additionally, the Monod (1980) study was undertaken in a short period of time with no information of the rivers and regions where the specimens were collected. The present study took into consideration eight main rivers of the three regions that rim the coastal area, coupled with 1 year of data collection.

There was differential distribution of species across the three regions. The Littoral region had the least species abundance with only four species sampled, all of which were also present in the South West and South regions. South West and South region recorded the same number of species (6) with the difference that M. felicinum was found only in the South region and the undescribed species M. sp found only in one river (Batoke River) in the South West region. The absence of M. sp in two other rivers of the same region (Yoke and Mabeta rivers) could be due to the relatively high dissolved oxygen recorded in these two rivers. It may also be a habitat selection for M. sp. Given that M. sp has been identified for the first time in Cameroon, further studies on its biology and ecology are highly recommended.

The relationship between the species identified in this study based on morphological features is the same as that observed in the Makombu et al. (2015) and Konan (2009) studies. The only difference is the identification of a new species, christened in this study as M. sp. The concordance between this phenotypic relationship and the genetic relationship based on DNA analysis served as the basis of this study. This is important given the influence that environmental factors have on morphological characteristics. It is possible that similar ecotypes sourced from different regions could be identified differently. At the genetic level, DArT markers used in the present study displayed fairly low polymorphism information content (average PIC = 0.15). These low values of PIC deviate from those seen in other commercially important nonaquatic species (PIC values range between 0.30 and 0.44; Raman et al., 2010; Sánchez‐Sevilla et al., 2015; Wenzl et al., 2004). The use of DArT in characterization of animals (and particularly aquatic animals) has been limited (Melville et al., 2017). In this study, even though up to 50,000 SNP markers were available after genotyping, only 1,814 met the criterion for further analysis, which limits the extent of the genetic diversity that can be captured. A larger study with more robust markers is paramount to completely characterize the genetic structure and relationships among the target species.

The low genetic distance between M. dux and M. sollaudii, indicated from F ST values, PCA clustering, and admixture results indicate very high genetic similarity between them. Whereas in this study we do not have conclusive evidence to suggest they are the same species, at the genetic level they seem to be highly similar. The phenotypic differences seen between them may be due to differential expression of genes that control the morphometric features used for classification (Dimmock et al., 2004). The phenotypic differences observed may also be the possibility of morphotypes within a species. M. sollaudii male has 2nd pereiopods (chelipeds) more developed than M. dux male, this could be two male morphotypes of a same species. Moreover, looking at the sex ratio, male highly dominate female in M. sollaudii collected in the three regions (>90% male). Cases of morphotypes within the genus Macrobrachium have been documented. Kuris et al. (1987) reported three male morphotypes of M. rosenbergii: the dominant blue clawed males (BC), the subordinate orange clawed males (OC), and the nonterritorial small clawed males (SM). Wortham and Maurik (2012) also reported three morphotypes within M. grandimanus (Randall, 1840): females, small symmetrical males, and large asymmetrical males. Study on morphotypic differentiation of species of this group of prawn is highly recommended.

Similarly, the results from this study indicate that M. macrobranchion and M. vollenhovenii are highly related and could represent panmictic populations. The admixture results at K = 5 allude to two distinct genetic stocks that exhibit the possibility of interbreeding and extensive gene flow to give rise to admixed individuals. The colocation of these species in the same rivers and habitat, as well as their amphidromous behavior patterns characterized by female migration from rivers to estuaries following hatching, larval development in saltwater, and a return upriver migration by postlarvae (Bauer and Delahoussaye, 2008), possibly provides ample opportunity for mating and hence gene flow between these two species. The lack of genetic differentiation between these species has been previously observed. J. G. Makombu et al. (unpublished results) observed similar results using mitochondrial DNA, increasing the possibility that they are descended from the same maternal genetic stock. Konan (2009) also found no genetic differentiation between M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion using enzymatic polymorphism. However, given the quite divergent marker profiles observed, there is evidence to suggest that these species are different. The large differences in number of polymorphic markers and genetic heterozygosity measures observed point to significant differentiation driven by differential speciation. The fact that they are colocated in the same rivers and habitats rules our differential manifestation of environmental influences. Perhaps a study of differential gene expression may shed more light as to the genetic basis of the huge phenotypic differences. It is instructive to note that during morphological analyses, specimens having characteristics of both of M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion were found. These “hybrid” individuals may represent the admixed individuals borne out of the two species. This could not be further investigated owing to limited resources available for this study. Given the relatively small marker set used, a deeper characterization of these species using dense genetic markers (both organellar and autosomal) would be necessary to remove any doubts as to the genetic relationship between them.

In contrast to the admixture results, both the PCA and the genetic distance estimates visualized by the phylogenetic tree separated M. sp from M. felicinum. The lack of differentiation based on genetic admixture could be because of small number of samples used for genotyping (M. sp: N = 5; M. felicinum: N = 5), which would limit differences in allelic patterns observable. Both species have low relative abundance; hence, the lower number of samples is obtained. Despite their close similarity in terms of phenotypic and morphometric features, they are not located in the same habitat; hence, there is reasonable chance to conclude that they are different species.

According to Dimmock et al. (2004), Macrobrachium is a notoriously difficult genus taxonomically, as the morphological plasticity of important traits changes extensively and gradually during the growth and is influenced by environmental parameters. Morphologically similar species are often quite genetically distinct. Analogous situations have been reported for some marine crustaceans (Knowlton, 2000) and freshwater macroinvertebrates (Baker, Hughes, Dean, & Bunn, 2004; Shih, Ng, & Chang, 2004).

The perils of morphological taxonomy of species of the genus Macrobrachium have been recorded in previous studies (Murphy & Austin, 2005; Vergamini et al., 2011). So far, many studies have called into question morphological classification of members of this group (Boulton & Knott, 1984; Fincham, 1987; Holthuis, 1952). Additionally, Qing‐Yi et al. (2009), Murphy and Austin (2002, 2004), and Short (2004) invalidated current morphologically based classification of Asian Macrobrachium species. Holthuis (1952) listed a number of reasons why classification of this genus is very difficult. These include a restricted number of characters available for identification, with many features common to all species, sexual dimorphism, and some species possibly being sexually mature before all body parts are fully developed. Use of molecular markers allows us to detect the genetic uniqueness of a particular individual, species, or population irrespective of the challenges enumerated above (Maralit & Santos, 2015).

5. CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated that the use of morphological parameters for the classification of Macrobrachium species of the coastal area of Cameroon is fraught with possible misclassification especially for species that are panmictic with high gene flow. Genetic characterization has confirmed that M. chevalieri is a genetically different species from M. sp and M. felicinum despite morphological similarity. Additionally, M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion display great gene flow between two genetic backgrounds, likely as a result of a panmictic population undergoing localized divergence, while M. dux and M. sollaudii seem to be conspecific. However, the results obtained in this study were limited by the low average PIC value and call rate of DArT markers used, coupled with the small number of individual used for some species. This study constitutes a critical first step in developing a genetic test for accurate identification of Macrobrachium species of coastal Cameroon.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Evans K. Cherulyot and Fidalis D. N. Mujibi were employed by company USOMI, and Eric Mialhe was employed by company Concepto Azul. All other authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JM, FS, FM, EM, and PO conceived and coordinated the work. JM, ET, PZ, AE, AN, and BO acquired data. FM, FS, EC, GT, OS, ET, and JN analyzed and interpreted the data. JM drafted the manuscript. FS, FM, GT, and OS contributed to revisions and edits of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by two organizations: The BecA‐ILRI Hub through the Africa Biosciences Challenge Fund (ABCF) program. The ABCF Program is funded by the Australian Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) through the BecA‐CSIRO partnership; the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA); the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF [OPP:1075938]); the UK Department for International Development (DFID); and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). The International Foundation for Science, Stockholm, Sweden, through a grant to Judith Georgette Makombu.

APPENDIX 1.

Detailed description of morphometric and meristic characters used in this study

| No. | Characters | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphometric | |||

| 1 | Total length | TL | Distance between rostrum tip and the distal tip of the telson with shrimp stretched out |

| 2 | Carapace length | CL | Distance between the posterior margin of the right orbit and the midpoint of the posterior margin of the carapace |

| 3 | Rostrum length | R | Distance of epigastric tooth basis to rostrum tip |

| 4 | Head length | H | Distance between the rostrum tip and the midpoint of the posterior margin of the carapace |

| 5 | Telson length | Te | Distance of posterior margin of sixth abdominal somite to telson tip |

| 6 | Telson width | Tew | Distance between lateral margin of telson taken in his basis |

| 7 | Carapace width | Cw | Distance between lateral margin of cephalothorax |

| 8 | Carapace height | CH | Distance between dorsal and ventral end of carapace |

| 9 & 10 | Pereiopod length | L1 & L2 | Distance between the proximal margin of the ischium and the distal tip of propodus |

| 11 & 12 | Ischium length | I1 & I2 | Distance from the proximal to the distal end of ischium |

| 13 & 14 | Merus length | M1 & M2 | Distance between proximal and distal margin of merus |

| 15 & 16 | Carpus length | C1 & C2 | Distance from the proximal to the distal end of carpus |

| 17 & 18 | Palm length | P1 & P2 | Distance between proximal and distal margin of palm |

| 19 & 20 | Dactylus length | D1 & D2 | Distance between proximal and distal margin of dactyl |

| 21 & 22 | Distal tooth‐fixed digit tip | Df1 & Df2 | Distance from distal tooth of fixed digit to propodus tip |

| 23 & 24 | Distal tooth‐dactylus tip | Dt1 & Dt2 | Distance from distal tooth of dactylus tip |

| 25 & 26 | Ischium width | Iw1 & Iw2 | Distance between lateral line of ischium |

| 27 & 28 | Merus width | Mw1 & Mw2 | Distance between lateral line of merus |

| 29 & 30 | Carpus width | Caw1& Caw2 | Distance between lateral line of carpus |

| 31 & 32 | Palm width | Pw1 & Pw2 | Distance between lateral line of palm |

| 33 | Eye diameter | ED | Distance between lateral lines of orbit taken on right eye |

| Meristics | |||

| 1 | Dorsal teeth | Dr | Teeth number on rostrum dorsal line |

| 2 | Ventral teeth | Vr | Teeth number on rostrum ventral line |

| 3 | Postorbital teeth | Po | Number of rostrum postorbital teeth |

| 4 | Spines of telson | St | Spines number on telson dorsal face |

| 5 | Spine of palm | Sp | Spines number on interne lateral line of palm |

| 6 | Dactylus teeth | Dt | Number of dactylus teeth |

APPENDIX 2.

Identification keys of Macrobrachium

-

a

Key to family and genus (Monod, 1980)

Legs of the first two pairs of pereiopods different and finished by pincers; legs of the second pair are well developed and end with strong pincers; rostrum is developed and has teeth on both sides; medium to large or very large size (45–182 mm) …… Palaemonidae (Macrobrachium).

-

b

Key to species of Macrobrachium according to Konan, 2009

-

1

The carpus of the second pereiopod is shorter or same length with the merus, the ratio of the length of carpus/length of merus is <1.08 …… 2

The carpus of the second pereiopod is longer than the merus; the ratio of the length of carpus/length of merus is >1.08 …… 3

-

2

The merus is 0.20–0.27 times longer than large; the length of the carpus is 0.70–0.95 times the length of the palm; the rostrum tip is at the same level or longer than the antenna scale …… M. macrobrachion

The merus is 0.27–0.47 times longer than large; the length of the carpus is 0.45–0.75 times the length of the palm; the rostrum tip is shorter than the extremity of the antenna scale …… M. vollenhovenii

-

3

The carpus is longer than the palm (length of carpus/length of palm = 1.17–1.39); the merus is as long or longer than the palm (M/P1 = 0.98–1.14) …… 4

The carpus is shorter or the same length with the palm (length of carpus/length of palm = 0.61–1); the merus is shorter than the palm (M/P1 = 0.58–0.90) …… 5

-

4

The merus length is greater than the palm length (M/P1 = 1.02–1.06); the carpus length is greater than the carapace length (103.40%–149.91% Carapace length); the length of the ischium/length of merus is <2/3 …… M. sollaudii

The merus length and palm length are almost the same (M/P1 = 0.98–0.99); the carpus length is less than the carapace length (61.13%–95.62% carapace length); the length of the ischium/the length of merus is >2/3 …… M. dux

-

5

Fingers not bent, but they touch each other throughout the entire length and do not possess internal fur …… M. thysi

Fingers bent, do not touch each other and possess internal fur …… M. felicinum

APPENDIX 3.

Collection site of 94 Macrobrachium samples

| Sample number | Species | Sex | Rivers | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Macrobrachium sp | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 2 | Macrobrachium sp | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 3 | Macrobrachium sp | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 4 | Macrobrachium sp | Female | Batoke | South West |

| 5 | Macrobrachium sp | Female | Batoke | South West |

| 6 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 7 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Batoke | South West |

| 8 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Yoke | South West |

| 9 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Yoke | South West |

| 10 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Mabeta | South West |

| 11 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Mabeta | South West |

| 12 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Mabeta | South West |

| 13 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Mabeta | South West |

| 14 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Mabeta | South West |

| 15 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | yoke | South West |

| 16 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Yoke | South West |

| 17 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Yoke | South West |

| 18 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 19 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Yoke | South West |

| 20 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Yoke | South West |

| 21 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Yoke | South West |

| 22 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Mabeta | South West |

| 23 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Mabeta | South West |

| 24 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Batoke | South West |

| 25 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Batoke | South West |

| 26 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Batoke | South West |

| 27 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 28 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 29 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 30 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Yoke | South West |

| 31 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Yoke | South West |

| 32 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Mabeta | South West |

| 33 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Female | Mabeta | South West |

| 34 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 35 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Batoke | South West |

| 36 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Nkam | Littoral |

| 37 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Nkam | Littoral |

| 38 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 39 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 40 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 41 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 42 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 43 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 44 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 45 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 46 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 47 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 48 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 49 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 50 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 51 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 52 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 53 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Nkam | Littoral |

| 54 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Nkam | Littoral |

| 55 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 56 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Female | Wouri | Littoral |

| 57 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 58 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Wouri | Littoral |

| 59 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Lobe | South |

| 60 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Lobe | South |

| 61 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Male | Lokoundje | South |

| 62 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 63 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Female | Kienke | South |

| 64 | Macrobrachium chevalieri | Male | Kienke | South |

| 65 | Macrobrachium felicinum | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 66 | Macrobrachium felicinum | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 67 | Macrobrachium felicinum | Male | Lokoundje | South |

| 68 | Macrobrachium felicinum | Female | Lobe | South |

| 69 | Macrobrachium felicinum | Male | Lobe | South |

| 70 | Macrobrachium felicinum | Male | Kienke | South |

| 71 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 72 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Lokoundje | South |

| 73 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Lobe | South |

| 74 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Lobe | South |

| 75 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Female | Kienke | South |

| 76 | Macrobrachium macrobrachion | Male | Kienke | South |

| 77 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Kienke | South |

| 78 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Kienke | South |

| 79 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Lokoundje | South |

| 80 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 81 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Male | Lobe | South |

| 82 | Macrobrachium vollenhovenii | Female | Lobe | South |

| 83 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Kienke | South |

| 84 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Lobe | South |

| 85 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Lokoundje | South |

| 86 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 87 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Male | Lobe | South |

| 88 | Macrobrachium sollaudii | Female | Kienke | South |

| 89 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Lobe | South |

| 90 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Kienke | South |

| 91 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Kienke | South |

| 92 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Lokoundje | South |

| 93 | Macrobrachium dux | Female | Lokoundje | South |

| 94 | Macrobrachium dux | Male | Lobe | South |

Makombu JG, Stomeo F, Oben PM, et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of freshwater prawn of genus Macrobrachium in the coastal area of Cameroon. Ecol Evol. 2019;9:14217–14233. 10.1002/ece3.5854

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Link for the data: GPS points: https://figshare.com/s/08de4b966929dfd56881; Morphological data: https://figshare.com/s/827a37559c806e7c11b6; Molecular data: https://figshare.com/s/3af1e859f4622ea27f1d.

REFERENCES

- Alexander, D. , Novembre, J. , & Lange, K. (2009). Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Research, 19, 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association (APHA) (1998). Standard method for examination of water and wastewater, 20th ed. (p. 1150). Washington DC: American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, N. , Edwards, D. , & Batley, J. (2009). New technologies for ultra‐high throughput genotyping in plants. Methods in Molecular Biology, 513, 19–39. 10.1007/978-1-59745-427-8_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A. M. , Hughes, J. M. , Dean, J. C. , & Bunn, S. E. (2004). Mitochondrial DNA reveals phylogenetic structuring and cryptic diversity in Australian freshwater macroinvertebrate assemblages. Marine and Freshwater Research, 55, 629–640. 10.1071/MF04050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R. T. , & Delahoussaye, J. (2008). Life history migrations of the amphidromous river shrimp Macrobrachium ohione from a continental large river system. Journal of Crustacean Biology., 28, 622–632. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, A. J. , & Knott, B. (1984). Morphological and electrophoretic studies of the Palaemonidae (Crustacea) of the Perth region, Western Australia. Australia Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 35, 769–783. 10.1071/MF9840769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann R., Hazelhurst S. 2015. Genesis manual. Technical Report 2015. University of the Witwatersrand http://www.bioinf.wits.ac.za/software/genesis/Genesis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. T. , Tsai, C. F. , & Tzeng, W. N. (2009). Freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium Bate, 1868) of Taiwan with special references to their biogeographical origins and dispersion routes. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 29, 232–244. 10.1651/08-3072.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Grave, S. , & Fransen, C. H. J. M. (2011). Carideorum catalogus: The recent species of the dendrobranchiate, stenopodidean, procarididean and caridean shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda). Zoologische Mededelingen, 89, 195–589. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock, A. , Willamson, I. , & Mather, P. B. (2004). The influence of environment on the morphology of Macrobrachium australiense (Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Aquaculture International, 12, 435–456. 10.1023/B:AQUI.0000042140.48340.c8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Divu, D. , Khushiramani, R. , Malathi, S. , Karunasagar, I. , & Karunasagar, I. (2008). Isolation, characterization and evaluation of microsatellite DNA markers in giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii, from South India. Aquaculture, 284, 281–284. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.07.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doume, C. N. , Toguyeni, A. , & Yao, S. S. (2013). Effets des facteurs endogènes et exogènes sur la croissance de la crevette géante d'eau douce Macrobrachium rosenbergii De Man, 1879 (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) le long du fleuve Wouri au Cameroun. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 7, 584–597. 10.4314/ijbcs.v7i2.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- E and D (2009). Elaboration d'un programme pour la surveillance de la qualite des eaux marines au Cameroun. Projet CAPECE (p. 1995). Rome, Italy: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Elshire, R. J. , Glaubitz, J. C. , Sun, Q. I. , Poland, J. A. , Kawamoto, K. , Buckler, E. S. , & Mitchell, S. E. (2011). A robust, simple genotyping‐by‐sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE, 6, e19379 10.1371/journal.pone.0019379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etim, L. , & Sankare, Y. (1998). Growth and mortality, recruitment and yield of freshwater shrimp, Macrobrachium vollenhovenii Herklots, 1857 (Crustacea, Palaemonidae) in the Faye reservoir, Côte d'Ivoire, West Africa. Fisheries Research, 38, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L. , & Lischer, H. E. L. (2010). Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources, 10, 564–567. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, A. A. (1987). A new species of Macrobrachium (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae) from the Northern territory, Australia and a key to Australian species of the genus. Zoologica Scripta, 16, 351–354. 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1987.tb00080.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folack, J. (1995). Etat de la pollution marine et côtière au Cameroun. Yaounde, Cameroun: Rapp. Consultation, Projet CMR/92/008 sur le Plan National de Gestion de l'Environnement (PNGE), MINEF/PNUD. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati, O. , Mosseron, M. , & Keith, P. (2002). Distribution and habitat utilization in two Atyid shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda) in rivers of Nuku‐Hiva Island (French Polynesia). Hydrobiologia, 472, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, L. B. (1952). A general revision of the Palaemonidae (Crustacea, Decapoda, Natantia) of the Americas. Part II. The subfamily Palaemonidae. Occasional Papers of the Allan Hancock Foundation, 12, 1–396. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, L. B. (1980). FAO species catalogue. Vol. 1. Shrimps and prawns of the world. An annotated catalogue of species of interest to fisheries FAO fisheries symposium (Vol. 1, pp. 1–261). [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, L. B. , & Ng, P. K. L. (2010). Nomenclature and taxonomy In New M. B., Valenti W. C., Tidwell J. H., D'Abramo L. R., & Kutty M. N. (Eds.), Freshwater prawns: Biology and Farming (pp. 12–17). Oxford, England: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Huson, D. H. , & Bryant, D. (2006). Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 23, 254–267. 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imelfort, M. , Batley, J. , Grimmond, S. , & Edwards, D. (2009). Genome sequencing approaches and successes In Somers D., Gustafson P., & Langridge P. (Eds.), Methods in molecular biology, plant genomics (pp. 345–358). New York: Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian, A. , Wenzl, P. , Huttner, E. , Carling, J. , Xia, L. , Blois, H. , … Uszynski, G. (2012). Diversity arrays technology: A generic genome profiling technology on open platforms. Methods in Molecular Biology, 888, 67–89. 10.1007/978-1-61779-870-2_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton, N. (2000). Molecular genetic analyses of species boundaries in the sea. Hydrobiologia, 420, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Konan, K. M. (2009). Diversité morphologique et génétique des crevettes des genres Atya Leach, 1816 et Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 de Côte d'Ivoire. PhD thesis, Université d'Abobo Adjamé, Côte d'Ivoire. [Google Scholar]

- Kuris, A. M. , Ra'anan, Z. , Sagi, A. , & Cohen, D. (1987). Morphotypic differentiation of male Malaysian giant prawns, Macrobrachium rosenbergii . Journal of Crustacean Biology, 7, 219–237. 10.2307/1548603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lefébure, T. , Douady, C. J. , Gouy, M. , & Gilbert, J. (2006). Relationship between morphological taxonomy and molecular divergence within crustacea: Proposal of molecular threshold to help species delimitation. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 40, 435–447. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Y. , Cai, Y. X. , & Tzeng, C. S. (2007). Molecular systematics of the freshwater prawn genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) inferred from mtDNA sequences, with emphasis on East Asian species. Zoological Studies, 46, 272–289. [Google Scholar]

- Makombu, J. G. , Oben, B. O. , Oben, P. M. , Makoge, N. , Nguekam, E. W. , Gaudin, G. L. P. ,&... Brummett, R. E. (2015). Biodiversity of species of the genus Macrobrachium (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in Lokoundje, Kienke and Lobe Rivers, South Region, Cameroon. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Science, 7, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Maralit, B. A. , & Santos, M. D. (2015). Molecular markers for understanding shrimp biology and populations In Caipang C. M., Bacano-Maningas M. B. I., & Fagutao F. F. (Eds.), Biotechnological Advances in Shrimp Health Management in the Philippines (pp. 135–148). Kerala, India: Research Signpost. [Google Scholar]

- March, J. G. , Pringle, C. M. , Townsend, M. J. , & Wilson, A. I. (2002). Effects of freshwater shrimp assemblages on benthic communities along an altitudinal gradient of a tropical island stream. Freshwater Biology, 47, 377–390. 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00808.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marioghae, I. E. (1990). Studies of fishing methods, gear and marketing of Macrobrachium in the Lagos area. Lagos, Nigeria: Nigerian institute of Oceanography and Marine Research Technical, Paper 53. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, J. , Haines, M. L. , Boysen, K. , Hodkinson, L. , Kilian, A. , Smith Date, K. L. , … Parris, K. M. (2017). Identifying hybridization and admixture using SNPs: Application of the DArTseq platform in phylogeographic research on vertebrates. Royal Society Open Science, 4, 161061 10.1098/rsos.161061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod, T. (1966). Crevettes et crabes des côtes occidentales d'Afrique In Gordon I., Hall D. N. F., Monod T., Guinot D., Postel E., Hoestlandt H., & Mayrat A. (Eds.), Réunion de spécialistes C. S. A. sur les crustacés (pp. 103–234). Zanzibar, Tanzania: Mémoires de l'Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire. [Google Scholar]

- Monod, T. (1980). Décapodes In Durand J. R., & Leveque C. (Eds.), Flore et faune aquatiques de l'Afrique sahélo‐soudanienne (pp. 369–389). Paris, France: Tome I, ORSTOM. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N. P. , & Austin, C. M. (2002). A preliminary study of 16S rRNA sequence variation in Australian Macrobrachium shrimps (Palaemonidae: Decapoda) reveals inconsistencies in their current classification. Invertebrate Systematics, 16, 697–701. 10.1071/IT01031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N. P. , & Austin, C. M. (2003). Molecular taxonomy and phylogenetics of some species of Australian palaemonid shrimp. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 23, 169–177. 10.1163/20021975-99990324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N. P. , & Austin, C. M. (2004). Multiple origins of Australian endemic Macrobrachium (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) based on 16S rRNA mitochondrial sequences. Australian Journal of Zoology, 52, 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N. P. , & Austin, C. M. (2005). Phylogenetic relationships of the globally distributed freshwater prawn genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae): Biogeography, taxonomy and the convergent evolution of abbreviated larval development. Zoologica Scripta, 34, 187–197. 10.1111/j.1463-6409.2005.00185.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- New, M. B. (2002). Farming freshwater prawns: A manual for the culture of the giant river prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). Rome, Italy: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, F. M. , & Wolfi, M. (2006). Population dynamics of the giant African River prawn Macrobrachium vollenhovenii Herklots 1857 (Crustacea, Palaemonidae) in the Cross River Estuary, Nigeria. West Africa Journal of Applied Ecology, 9, 78–92. 10.4314/wajae.v9i1.45681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okogwu, O. I. , Ajuogu, J. C. , & Nwani, C. D. (2010). Artisanal fishery of the exploited population of Macrobrachium vollenhovenii Herklot 1857 (Crustacea; Palaemonidae) in the Asu River, Southeast Nigeria. Acta Zoologica Lituanica, 20, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Pileggi, L. G. , & Mantelatto, F. L. (2010). Molecular phylogeny of the freshwater prawn genus Macrobrachium (Decapoda, Palaemonidae), with emphasis on the relationship among selected American species. Invertebrate Systematics, 24, 194–208. 10.1071/ISO9043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, S. , Neale, B. , Todd‐Brown, K. , Thomas, L. , Ferreira, M. A. , Bender, D. , … Sham, P. C. (2007). PLINK: A tool set for whole‐genome association and population‐based linkage analyses. American Journal of Human Genetics, 81, 559–575. 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing‐yi, Z. , Qi‐qun, C. , & Wei‐bing, G. (2009). Mitochondrial COI gene sequence variation and taxonomy status of three Macrobrachium species. Zoological Research, 30, 613–619. 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2009.06613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available online at https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rodier, J. , Legube, B. , Marlet, N. , & Brunet, R. (2009).L’analyse de l’eau. 9e édition. Paris: DUNOD. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, H. , Stodart, B. J. , Cavanagh, C. , Mackay, M. , Morell, M. , Milgate, A. , & Martin, P. (2010). Molecular diversity and genetic structure of modern and traditional landrace cultivars of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Crop and Pasture Science, 61, 222–229. 10.1071/CP09093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, N. , & Mantelatto, F. L. (2013). Molecular analysis of the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium olfersii (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) supports the existence of a single species throughout its distribution. PLoS ONE, 8, e54698 10.1371/journal.pone.0054698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Sevilla, J. F. , Horvath, A. , Botella, M. A. , Gaston, A. , Folta, K. , Kilian, A. , … Amaya, I. (2015). Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) marker platforms for diversity analysis and linkage mapping in a complex crop, the octoploid cultivated strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). PLoS ONE, 10, e0144960 10.1371/journal.pone.0144960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih, H. T. , Ng, P. K. L. , & Chang, H. W. (2004). Systematics of the genus Geothelphusa (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura, Potamidae) from southern Taiwan: A molecular appraisal. Zoological Studies, 43, 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J. W. (2004). A revision of Australian river prawns, Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Hydrobiologia, 525, 1–100. 10.1023/B:HYDR.0000038871.50730.95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tchakonté, S. , Ajeagah, G. , Diomandé, D. , Camara, A. I. , Konan, K. M. , & Ngassam, P. (2014). Impact of anthropogenic activities on water quality and freshwater shrimps diversity and distribution in five rivers in Douala, Cameroon. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, 4, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Vergamini, F. G. , Pileggi, L. G. , & Mantelatto, F. L. (2011). Genetic variability of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae). Contributions to Zoology, 80, 67–83. 10.1163/18759866-08001003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzl, P. , Carling, J. , Kudrna, D. , Jaccoud, D. , Huttner, E. , Kleinhofs, A. , & Kilian, A. (2004). Diversity arrays technology (DArT) for whole‐genome profiling of barley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 9915–9920. 10.1073/pnas.0401076101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortham, J. L. , & Maurik, L. N. (2012). Morphology and morphotypes of the Hawaiian river shrimp, Macrobrachium grandimanus . Journal of Crustacean Biology, 32, 545–556. 10.1163/193724012X637311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wowor, D. , Muthiu, V. , Meier, R. , Balke, M. , Cai, Y. , & Ng, P. K. L. (2009). Evolution of life history traits in Asian freshwater prawns of the genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) based on multilocus molecular phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution, 52, 340–350. 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Link for the data: GPS points: https://figshare.com/s/08de4b966929dfd56881; Morphological data: https://figshare.com/s/827a37559c806e7c11b6; Molecular data: https://figshare.com/s/3af1e859f4622ea27f1d.