Abstract

Burn injury in children results in a systemic inflammatory reaction as well as a stress response. Consequences of these non-specific adaptive responses include resorptive bone loss and muscle catabolism. These adverse events can result in a post-burn fracture rate of approximately 15% and long-term muscle weakness that prolongs recovery. A randomized controlled trial of a single dose of the bisphosphonate pamidronate within the first ten days of burn injury resulted in the prevention of resorptive bone loss and continuous bone accrual. Examining the muscle protein kinetics in pediatric burn patients enrolled in that randomized controlled trial revealed that those who had been given the single dose bisphosphonate experienced preservation of muscle mass and strength. An in vitro study of mouse myoblasts incubated with serum from patients who participated in the randomized controlled study demonstrated that mouse myoblasts exposed to serum from patients given the single dose bisphosphonate exhibited greater myotube diameter than those from burned children given placebo. Moreover, the serum from bisphosphonate treated patients stimulated the protein anabolic pathways and suppressed protein catabolic pathways in these cells. Inasmuch as incubation of the myotubes with an antibody to transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) rescued myotube size in the cultures with serum from patients who received the placebo to the same magnitude as cultures with serum from patients treated with single dose bisphosphonate, we postulate that post-burn bone resorption liberates muscle catabolic factors which cause muscle wasting. Future uses of bisphosphonates could include studies designed to prevent short-term acute bone resorption in conditions that may result in muscle wasting as well as in short-term interventions in chronic inflammatory conditions which may flare and cause acute bone and muscle loss.

Keywords: bisphosphonates, bone loss, muscle loss, burns, muscle catabolic factors

1. INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this manuscript is to identify new conditions in which the use of bisphosphonates may potentially be therapeutic. At the recently concluded molecular pharmacology workshop at the University of Sheffield celebrating the 50th anniversary of the first publication on bisphosphonates, my role was to help identify future uses of bisphosphonates and one subject came up which could not have been anticipated at the time bisphosphonates were introduced to medicine: preservation of muscle mass.

While this application may not pertain to all instances in which muscle wasting occurs in human pathology, this paper will illustrate several potential applications of bisphosphonates when applied to managing the consequences of pediatric burn injury.

2. CONSEQUENCES OF PEDIATRIC BURN INJURY

A recently published discussion (1) of the effects of burn injury on the musculoskeletal system and the musculoskeletal contribution to the maintenance of post-burn hypermetabolism should serve as a good reference for the following summary. Burn injury results in three immediate adaptive responses by the body: a systemic inflammatory response, a stress response, and a hypermetabolic response that sustains both.

2.1. Systemic Inflammatory Response

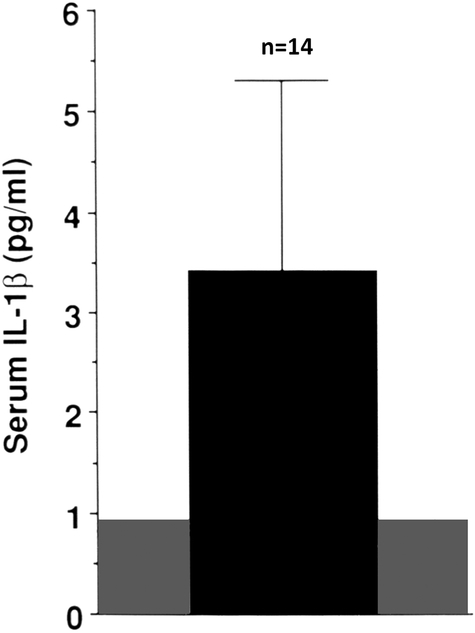

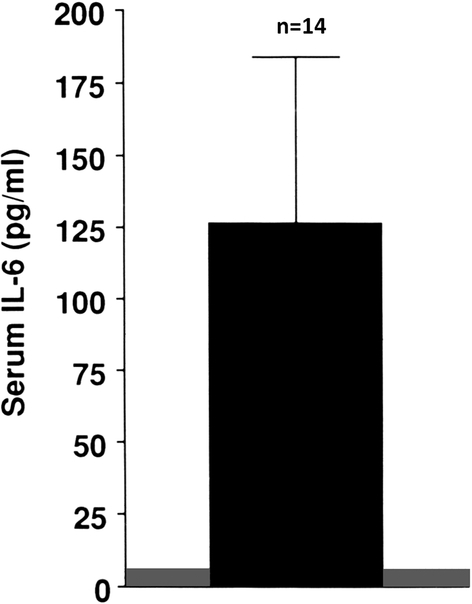

The acute inflammatory response occurs given the burn’s destruction of the skin barrier to microorganisms. Its onset is within the first 24 hours following a burn, marked by increased production of various pro-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, at two weeks post-burn serum concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1 β are increased three-fold and IL-6 concentrations are increased one hundred-fold (2), see Figures 1 and 2. These pro-inflammatory cytokines can contribute to the immediate onset of bone resorption, which occurs as early as the first post-burn day (3). Moreover, bone resorption liberates calcium, which has been reported to stimulate peripheral blood mononuclear cell chemokine production as well as inhibition (4) and to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in increased monocyte and macrophage production of IL-1 (5). Thus, inflammatory cytokine-induced bone resorption results in potential prolongation and intensification of the systemic inflammatory response (6)..

1.

Serum concentration of interleukin-1 β (IL-1β in pediatric burns patients at 2 weeks post-burn. The shaded area represents the normal range. Modified from Klein et al, Bone (2).

2.

Serum concentration of IL-6 in pediatric burns patients at 2 weeks post-burn. The shaded area represents the normal range. Modified from Klein et al Bone (2).

2.2. Stress Response

In addition to the systemic inflammatory response, the stress response is initiated early following burn injury. This response results in the increase in endogenous production of both catecholamines and glucocorticoids. The effects of the catecholamine response on the skeleton have not been fully characterized, while the 3–8-fold elevation in urinary cortisol excretion indicates a sustained increase in endogenous glucocorticoid production that can last through the entire first year following the burn (2, 7). Glucocorticoids contribute to reduced bone formation, seen in rats as early as three days following a burn (8). By two to three weeks following a burn, there is a reduction in both bone resorption and formation, leading to a low turnover state (2) and a consequent inability of the body to recover the lost bone, which is 7% of lumbar spine bone mineral content by three weeks post-burn and 3% of total body bone mineral content by 6 months post-burn (9). The consequences of the resorptive bone loss include a post-burn fracture rate of up to 15% after one year post-burn (10) in one study and a doubling of annual extrapolated fracture incidence in boys and a 50 % increase in annual extrapolated fracture incidence in girls in another (11).

2.3. Muscle Atrophy

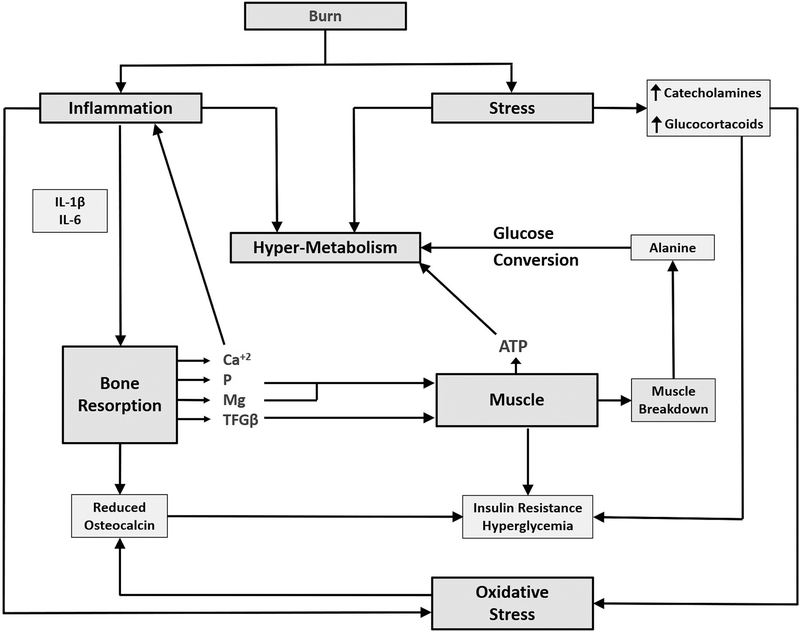

The rapid loss of muscle may be multifactorial. Mitochondrial injury and excessive heat production have been implicated (12). Inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-6, may result in muscle wasting (13), as may endogenous glucocorticoid production. While these considerations have been entertained in the majority of discussions of post-burn hypermetabolic muscle wasting, we have recently identified an additional factor, a description of which as well as an explanation of its role in muscle loss takes place in a separate section. Regardless of etiology, muscle loss has complicated post-burn rehabilitation and serves as a barrier to burn recuperation and re-integration into society. Figure 3 (1) illustrates the complex interactions of the musculoskeletal system with the body’s metabolism following burn injury. For example, a reduction in bone mass and hence osteocalcin production results from the imbalance of the increased bone resorption and the acute reduction of bone formation. As previously discussed (1) release of calcium, phosphate and magnesium following bone resorption result in sustained inflammation and increased phosphate and magnesium to support the increased muscle demand for ATP in an attempt to increase muscle protein synthesis.

3.

Model of interactions between muscle and bone following burns. The diagram illustrates several of the interactions between muscle and bone. The figure is modified from Klein, Metabolism (1), which contains a discussion of all the observations..

2.4. Etiology of Post-Burn Bone Loss

Thus, bone loss resulting from burn injury is likely a combination of various factors, including the robust resorptive effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines, the acute reduction in bone formation secondary to the suppressive effects of endogenous glucocorticoids on marrow stromal cell osteoblast precursors (7) and likely a contribution of oxidative stress resulting in the binding of FOXO to beta catenin in the nucleus of the osteoblast precursor cells, thus interfering with Wnt signaling (14). Lastly, the progressive muscle atrophy seen with post-burn catabolism would have reduced skeletal mechanical loading thus contributing to the resorptive bone loss.

3. HOW TO STOP THE BONE LOSS

When bone loss following burn injury first became apparent in adults (15) and in children (2,11), children were receiving recombinant human growth hormone, which did improve bone size, although not bone density, after approximately 12 months (16), preceded by a restoration of muscle mass between 6 and 9 months post-burn (16), suggesting that growth hormone acted by increasing skeletal loading. Recombinant human growth hormone, however, was expensive, and in adult patients in intensive care units, investigators demonstrated a relationship between recombinant human growth hormone administration and increased mortality (17). Oral oxandrolone served as a substitute for growth hormone and acted in the same fashion, with an increase in muscle mass preceding an increase in bone mass (18). However, the restoration of bone mass required at least a year of treatment in the case of either drug. In order to prevent the loss of bone rather than labor to restore lost bone, we undertook a double-blind randomized controlled trial of the bisphosphonate pamidronate in a pediatric burn population, electing to administer the drug once within the first ten days and a second dose one week afterward following the burn. The timing of the administration of pamidronate allowed us to take advantage of the window in which bone resorption was active (9).

3.1. Study Results

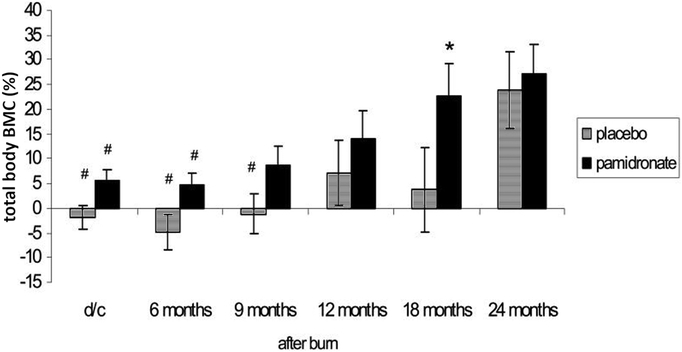

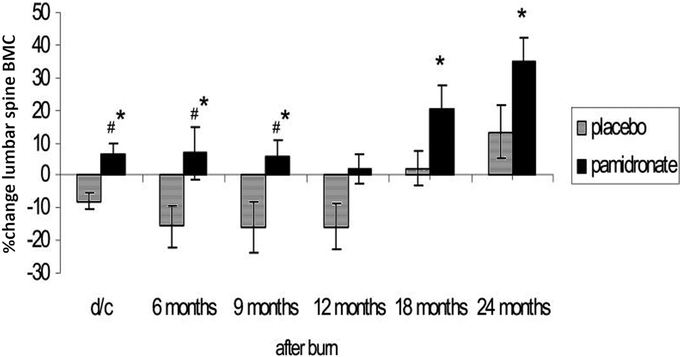

Using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry to follow the patients and un-blinding the results at six months after burn injury, we found that in those patients receiving pamidronate, bone mass accrual continued compared to admission bone density, while those receiving placebo lost 3% of their total body bone mineral content (80% cortical) over the six months and 7% of their lumbar spine bone mineral content (trabecular) after just the first three weeks (9). Following these un-blinded patients for up to 24 months demonstrated that the effects of pamidronate on the sparing of cortical bone lasted for 18 months post-burn, before the percentage gain in bone mass from acute admission in the placebo group recovered to the level of those receiving the bisphosphonate (Figure 4) and in the lumbar spine the significant difference in bone mass accrual in the pamidronate group remained for the entire 24 month period (19) as illustrated in Figure 5. Furthermore, at the conclusion of the 24-month study period, lumbar spine bone density was significantly higher in the group receiving single-dose pamidronate (19). On reviewing the data from that study it was apparent that while two doses of pamidronate were planned not all patients received both doses. There were no differences in outcomes between patients who received the two doses or the single dose of pamidronate. Therefore, we decided that the single dose was likely as effective as the planned two doses. We did not observe any complications from the single pamidronate dose, including osteonecrosis of the jaw or atypical femoral fractures. Furthermore, these complications did not occur in pediatric patients receiving bisphosphonate treatment for osteogenesis imperfecta, the most common condition treated by bisphosphonates (20). Thus, while the single-dose bisphosphonate treatment did not increase bone formation, it appeared to be effective in completely stopping the resorptive bone loss.

4.

Total body bone mineral content (BMC) expressed as a percentage of admission total body bone mineral content at discharge (d/c), 6–8 weeks post-burn, and at different time points up to two years post-burn. Modified from Przkora et al Bone (19). We followed 8 patients given pamidronate and 13 patients given placebo.

5.

Lumbar spine (LS) bone mineral content (BMC) expressed as a percentage of admission lumbar spine bone mineral content at discharge (d/c), 6–8 weeks post-burn, and at different time points up to two years post-burn. Modified from Przkora et al Bone (19). We followed 8 patients given pamidronate and 13 patients given placebo.

Thus, the merits of a trial of bisphosphonates after burn injury were at the very least a prevention of the resorptive bone loss occurring in the first two to three weeks following pediatric burn injury. Data on whether this treatment affected the incidence of post-burn fractures are not available as no fracture data have been collected by burn association data bases for this parameter. The potential benefits of bisphosphonate therapy were known to the burns community and no additional information was available until 2013. At that time, the results of stable isotope muscle protein kinetic studies in our patients appeared for the first time in a formal data base available to researchers.

4. MUSCLE PROTEIN KINETIC STUDIES IN PEDIATRIC BURNS PATIENTS: TYPICAL FINDINGS

As stated above, burn patients are catabolic (1). Researchers at our hospital had been studying muscle protein kinetics in pediatric burns patients for many years, developing methods of stable isotope balance studies and validating algorithms for determination of muscle protein synthesis, breakdown and balance. These methods can be reviewed elsewhere (21,22), but the basis for them is the use of a stable isotope of phenylalanine, an essential amino acid and thus not synthesized in muscle. When arterial and venous cannulae are placed, the rate of disappearance of infused phenylalanine from arterial blood represents the rate of muscle protein synthesis. Likewise, the rate of appearance of phenylalanine in venous blood represents the rate of muscle protein breakdown. Net balance can then be calculated. A second part of the protocol used to study the muscle protein kinetics in pediatric burn patients was an infusion of unlabeled amino acids. These serve as food for the muscle resulting in a spike in muscle protein synthesis (22).

4.1. Results of Muscle Protein Kinetic Studies in Burns Patients Receiving Single-Dose Pamidronate

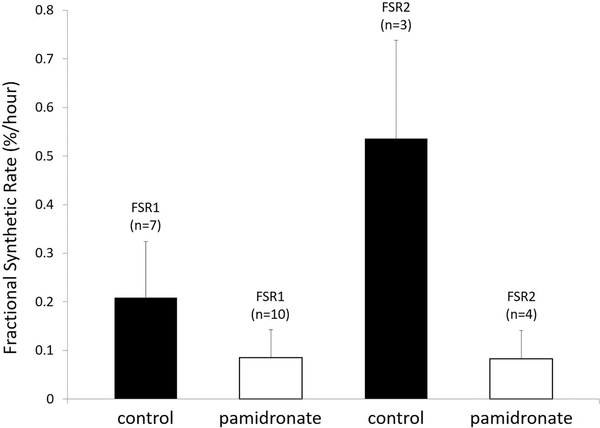

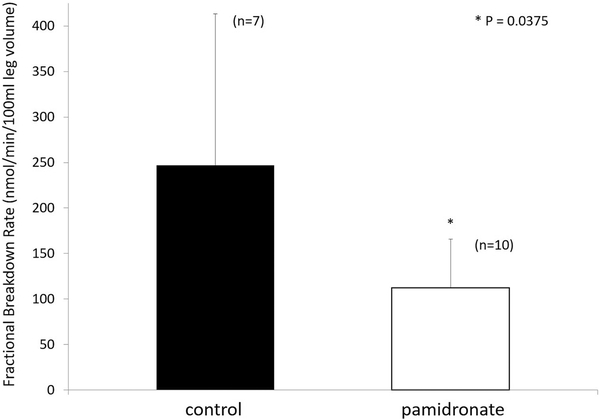

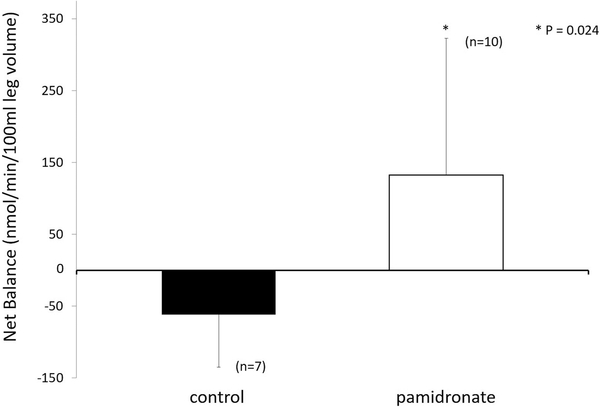

Upon examination of the database, we found muscle protein kinetics results from approximately 30% of the patients enrolled in the double-blind randomized controlled study over the first month post-burn. The following were determined. At 30 days post-burn, the rate of muscle protein synthesis was significantly reduced in the patients given pamidronate (Figure 6); muscle protein breakdown was also significantly reduced compared to placebo controls, as shown in Figure 7. Surprisingly, net muscle protein balance was positive in the patients given the single dose of pamidronate in contrast to the negative balance seen in the placebo controls, as shown in Figure 8. This difference in balance was also significant (22). Because these results were not obtained prospectively, and because the availability of data from these kinetics studies was not systematically determined by us, we sought corroboration of these results as well as a rationale for their occurrence.

6.

Fractional synthetic rate of muscle protein at 30 d post-burn. The first two bars from the left represent the rate of protein synthesis following infusion of a stable isotope of phenylalanine. The two bars on the right represent the rate of protein synthesis following an infusion of unlabeled amino acids. In each case the open bars representing muscle protein synthetic rate in burn patients who received single-dose pamidronate was significantly depressed compared to those who received placebo control. FSR= fractional synthetic rate. Modified from Borsheim et al (22).

7.

Fractional breakdown rate of muscle protein in burned patients who received placebo control (open bars) and those who received pamidronate (closed bars) at 30 days post-burn. Muscle protein breakdown was significantly reduced in the group treated with single-dose pamidronate. Modified from Borsheim et al (22).

8.

Net muscle protein balance in burned patients who received placebo control (filled bar) and those who received single-dose pamidronate (open bar). Muscle protein balance was positive in the group receiving single-dose pamidronate. Modified from Borsheim et al (22).

Accordingly, we undertook analyses of muscle biopsies from these study subjects at a comparable time period as well as an examination of muscle strength data from those of the randomized controlled study participants who underwent exercise training at 9 months post-burn.

4.2. Corroborating Results

On examination of muscle fiber diameter from the same pediatric burns subjects as participated in the randomized controlled trial at the same post-burn point in time, we found that those patients who received single-dose pamidronate in the randomized controlled trial had significantly greater fiber diameter than those receiving the placebo control (22). Furthermore, a small number of burn subjects (n=6 in study controls and n=5 in study pamidronate patients) who participated in the same randomized controlled study and were enrolled in weight-bearing exercise training at 9 months post-burn were evaluated for lower extremity peak torque as a baseline for the exercise study. Those patients who had received the single-dose pamidronate had peak torque values equivalent to normal unburned physically fit age-matched children (n=22) while those receiving the placebo tended to have lower peak torque, a trend which approached significance (p=0.052).Reliability of these data was limited, however by the small number of subjects (22). These findings serve as evidence supporting the findings of the muscle protein kinetic studies. Because the pamidronate study subjects who participated in the muscle protein kinetic studies were not systematically selected, a possibility of unanticipated distribution bias could have influenced the results. In order to determine whether the data from these stable isotope studies could be reproduced, a prospective randomized controlled study would have to be carried out. To date this has not been done.

Therefore, in order to obtain additional supportive evidence for the reported data (22), we collaborated with the laboratory of Dr Lynda Bonewald at Indiana University in order to learn if an underlying molecular mechanism for the preservation of muscle mass might help to explain our findings.

4.3. Results of In Vitro Experiments

We studied the potential difference in myotube size as generated by murine C2C12 myoblast differentiation into myotubes with 48h of exposure to serum from subjects in the randomized controlled study of single-dose pamidronate or placebo or from normal children. We found that incubation with serum from subjects receiving placebo significantly reduced myotube size compared to serum from normal unburned children. In contrast, incubation with serum from subjects receiving single-dose pamidronate resulted in rescue of myotube size (23). Examining signaling pathways by Western blot revealed that incubation with serum from placebo-treated subjects induced a reduction of the anabolic pathway as indicated by decreased phosphorylation of AKT and its downstream target mTOR (23). This pathway demonstrated rescue by incubation with serum from pamidronate-treated subjects. The catabolic ubiquitin pathway demonstrated suppression when incubated with serum from pamidronate-treated subjects (23). Finally, incubation of C2C12 myoblasts with serum from placebo-treated burned subjects and anti-TGFβ antibody demonstrated rescue of myotube size comparable to that achieved with serum from pamidronate-treated burn subjects while incubation with serum from single-dose pamidronate treated burn subjects and anti-TGFβ antibody did not result in a significant diameter increase in myotubes. These findings together suggested that bone resorption releases muscle catabolic factors such as TGFβ that stimulate muscle breakdown and suppress muscle protein synthesis (23). The findings are similar to those reported by Waning et al (24) in women with breast cancer metastases to bone and suggest that this response may be basic to resorptive conditions.

Burn serum has previously been shown to adversely affect muscle as shown by the work of Corrick et al (25), who showed that human satellite cells when allowed to differentiate into myoblasts and myotubes when exposed to burn serum showed an increase in STAT3 phosphorylation, impaired myogenesis and reduced myotube size. Further, Sehat et al (25) demonstrated that C2C12 murine myoblasts had increased caspase-3 activity when exposed to burn serum, suggesting an increase in cell death. This was associated with an increase in IL-6 associated mitochondrial fragmentation and impaired mitochondrial membrane potential. These effects were blocked by incubation with an IL-6 antibody. Corrick et al (26) reported findings consistent with these (26).

Moreover, earlier work by Yoon et al (27) in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy found that not only did pamidronate improve cortical bone architecture and resistance to fracture in addition to inhibition of remodeling, but it also improved muscle histology and grip strength. In addition, Chin et al (28) found that alendronate inhibited dexamethasone-induced myotube atrophy in C2C12 murine myoblasts in association with blockage of the dexamethasone-induced up-regulation of sirtuin 3 (SIRT3). A SIRT3 inhibitor also blocked dexamethasone-induced up-regulation of atrogin-1, thereby potentially protecting muscles from breakdown. All of the above reports were consistent with our findings

On the other hand, Bonnet et al (29) reported that while the anti-resorptive agent denosumab increased appendicular lean body mass in osteoporotic women, bisphosphonate treatment failed to do so. In the study by Borsheim et al (22) lean body mass was also examined by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry and failed to demonstrate a difference between pamidronate and placebo treated burn subjects. These data, being negative, were not reported in the original paper and were attributed to increased amounts of water in soft tissues to confound any difference that may have existed, a phenomenon complicating burn injuries. In osteoporotic women an accumulation of soft tissue water may not be the confounder. Possible alternative explanations could include either a lack of sensitivity of densitometry as a technique to measure muscle mass as opposed to total lean body mass, or the possibility that a threshold for rate of bone resorption exists, above which muscle catabolic factors accumulate in a clinically significant manner. In that situation the resorption seen in both breast cancer patients and pediatric burn patients may be sufficiently robust to trigger release of clinically significant quantities of muscle catabolic factors from bone. This issue is germane to future therapy because the mechanism of action of bisphosphonates and denosumab is different. Development of new therapies for muscle wasting conditions may depend on whether inhibition of osteoclast function or of the ligand of the receptor activator of NFKB (RANKL) is more important to the preservation of muscle mass during bone resorption or whether each plays a specific role.

5. FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

For any new studies concerning uses of bisphosphonates in the preservation of muscle mass several factors will need to be addressed. These are shown in Table 1 and include methods of accurately determining muscle mass and strength. These methods will need to be compared against each other for reproducibility as well as to precisely ascertain what each method actually measures. Another consideration may need to be the rate of bone resorption and how to quantitate it. Should it be by quantitation of biomarkers of resorption, by micro computed tomography (CT) of bone specimens identical anatomically and chronologically? Furthermore, if resorptive bone loss occurs at different rates within the same individual do we need to determine how sensitive changes in muscle fiber diameter are to these different rates of resorptive bone loss? Additional work needs also to be done on whether different types of muscle fibers are uniformly affected by muscle catabolic factors released from bone or whether one set of fibers is preferentially affected. When we learn the answers to these considerations we may be able to standardize methods of study of the effects of pharmacologic agents on the crosstalk between muscle and bone.

6. NEW TYPES OF POTENTIAL USES FOR BISPHOSPHONATES

Having mentioned the above considerations in future studies bisphosphonates merit investigation for various clinical uses. From what we have learned about their efficacy in muscle mass preservation in acute burns we know that they may have use in acute conditions which may result in significant inflammatory bone loss, such as sepsis or trauma. Other short term conditions may also benefit from the use of bisphosphonates. These might include preparations for organ transplantation in which the use of immunosuppressives such as glucocorticoids, cyclosporin or methotrexate may result in acute bone loss. To date we do not know how much muscle is lost in these conditions and investigations addressing this question are needed. Is muscle lost in chronic resorptive conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, primary or secondary? While bisphosphonates are used in conditions of immobilization, such as spinal cord injury, the role of bone resorption in muscle wasting in these conditions is also not known. Finally, are all bisphosphonates equally effective in all conditions in which they may be useful? Do new bisphosphonates need to be developed? How effective are bisphosphonates compared to other anti-resorptives such as RANKL inhibitors in each condition in which bisphosphonate treatment is ultimately proven to be useful? These potential uses are summarized in Table 2.

7. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

We have recently identified a mechanism in acute pediatric burns patients that suggests that pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated bone resorption releases muscle catabolic factors, such as TGFβ, that can stimulate cellular catabolic pathways such as ubiquitinase degradation and suppress anabolic pathways, such as that involving AKT and mTOR. The inflammation-associated muscle catabolism can be indirectly blocked by bisphosphonates by means of prevention of resorption of bone and consequent release of these muscle catabolic factors. This mechanism appears similar to what is reported in women with breast cancer metastases to bone. These findings give rise to new opportunities to identify new therapeutic uses for bisphosphonates in acute severe conditions as well as chronic hyper-resorptive conditions. More information is required to specifically identify the muscle catabolic factors released from bone, their specific effects on muscle, and the influence of differing rates of bone loss from different bones in order to better understand the possibilities for therapeutic uses of bisphosphonates in the future.

Highlights.

Burns cause systemic inflammation and endogenous glucocorticoid overproduction

Resultant inflammatory bone resorption and suppressed bone formation reduce bone mass

Increased resorption results in release of muscle catabolic factors such as TGFβ causing increased muscle catabolism and increased muscle wasting.

Bisphosphonates and other anti-resorptives can prevent the release of muscle catabolic factors from bone matrix sparing both bone and muscle.

Acknowledgements

These studies were funded by support of the National Institutes of Health NIGMS 1P50 GM-60338 Protocol 4 (GLK) and multiple grants from Shriners Hospitals for Children. The author is also grateful to Randal Morris from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Texas Medical Branch for his modifications of figures included in this text.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Klein GL The role of the musculoskeletal system in post-burn hypermetabolism. Metabolism 2019; 97: 81–6, doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein GL, Herndon DN, Goodman WG, Langman CB, Phillips WA, Dickson IR et al. Histomorphometric and biochemical characterization of bone following acute severe burns in children. Bone 1995; 17: 455–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein GL, Xie Y, Qin YX, Lin L, Hu M, Enkhbaatar P et al. Preliminary evidence of early bone resorption in a sheep model of acute burn injury: an observational study. J Bone Miner Metab 2014; 32: 136–41, doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0483-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein GL. The calcium-sensing receptor as a mediator of inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2016; 49: 52–6, doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossol M, Pierer M, Raulien N, Quandt D, Meusch U, Rothe K et al. Extracellular Ca2+ is a danger signal activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through G protein coupled calcium sensing receptors. Nat Commun 2012; 3: 1329, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein GL The role of calcium in inflammation-associated bone resorption. Biomolecules 2018; August 1; 8(3). Pii: E69, doi: 10.3390/biom8030069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein GL, Bi LX, Sherrard DJ, Beavan SR, Ireland D, Compston JE et al. Evidence supporting a role of glucocorticoids in short-term bone loss in burned children. Osteoporos Int 2004; 15: 468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Ayadi A, Helderman RC, Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Rosen CJ, Klein GL. Early reduced bone formation following burn injury in rats is not inversely related to marrow adiposity. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2019; published online 28 Aug 2019; doi.org. 10.1016/j.afos.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein GL, Wimalawansa SJ, Kulkarni G, Sherrard DJ, Sanford AP, Herndon DN. The efficacy of acute administration of pamidronate on the conservation of bone mass following severe burn injury in children: a double-blind, randomized controlled study. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16: 631–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayes T, Gottschlich MM, Khoury J, Kagan RJ. Investigation of bone health subsequent to vitamin D supplementation in children following burn injury. Nutr Clin Pract 2015; 30: 830–7, doi: 10.1177/0884533615587720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein GL, Herndon DN, Langman CB, Rutan TC, Young WE, Pembleton G et al. Long-term reduction in bone mass after severe burn injury. J Pediatr 1995; 126: 252–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogunbileje JO, Porter C, Herndon DN, Chao T, Abdelrahman DR, Papadimitriou A et al. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2016; 311: E336–E348, doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00535.2015 Epub 2016 Jul 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma JF, Sanchez BJ, Hall DT, Tremblay AK, Di Marco S, Gallouzi IE STAT3 promotes IFN¥/TNFα-induced muscle wasting in an NFκB-dependent IL-6 independent manner, EMBO Mol Med 2017; 9: 622–37, doi: 10.15252/emmm.201607052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manolagas SC From estrogen-centric to aging and oxidative stress: a revised perspective of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 2010; 31: 266–300, doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein GL, Herndon DN, Rutan TC, Sherrard DJ, Coburn JW, Langman CB et al. Bone disease in burn patients. J Bone Miner Res 1993; 8: 337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart DW, Herndon DN, Klein G, Lee SB, Celis M, Mohan S et al. Attenuation of post-traumatic muscle catabolism and osteopenia by long-term growth hormone therapy. Ann Surg 2001; 233: 827–34, doi: 10.1097/00000658-200106000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takala J, Ruokonen E, Webster NR, Nielsen MS, Zandstra DF, Vendelinckx G et al. Increased mortality associated with growth hormone treatment in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 785–92, doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909093411102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porro LJ, Herndon DN, Rodriguez NA, Jennings K, Klein GL, Mlcak R et al. Five-year outcomes after oxandrolone administration in severely burned children: a randomized clinical trial of safety and efficacy. J Am Coll Surg 2012; 214: 489–502, doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.211.12038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przkora R, Herndon DN, Sherrard DJ, Chinkes DL, Klein GL Pamidronate preserves bone mass for at least 2 years following acute administration for pediatric burn injury. Bone 2007; 41: 297–302, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggin A, Munns CF Long-term bisphosphonate therapy in osteogenesis imperfecta. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2017; 15: 412–18, doi: 10.1007/s11914-017-0401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuvendorj D, Chinkes DL, Zhang XJ, Ferrando AA, Elijah IE, Mlcak RP et al. Adult patients are more catabolic than children during acute phase after burn injury: a retrospective analysis on muscle protein kinetics. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37: 1317–22, doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-2223-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borsheim E, Herndon DN, Hawkins HK, Suman OE, Cotter M, Klein GL Pamidronate attenuates muscle loss after pediatric burn injury. J Bone Miner Res 2014; 29: 1369–72, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pin F, Bonetto A, Bonewald LF, Klein GL Molecular mechanisms responsible for the rescue effects of pamidronate on muscle atrophy in pediatric burn patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019. August 7; 10: 543, doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00543.eCollection 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waning DL, Mohammad KS, Reiken S, Xie W, Andersson DC, John S et al. TGF-β mediates muscle weakness associated with bone metastases in mice. Nat Med 2015; 21: 1262–71, doi: 10.1038/nm.3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sehat A, Huebinger RM, Carlson DL, Zang QS, Wolf SE, Song J. Burn serum stimulates myoblast cell death associated with IL-6 induced mitochondrial fragmentation. Shock 2017; 48: 236–42, doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrick KL, Stec MJ, Merritt EK. Windham ST, Thomas SJ, Cross JM et al. Serum from human burn victims impairs myogenesis and protein synthesis in primary myoblasts. Front Physiol 2015. June 16; 6: 184, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00184.eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon SH, Sugamori KS, Grynpas MD, Mitchell J Posiive effects of bisphosphonates on a mouse model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Neuromuscul Disord 2016; 26: 73–84, doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin H-C, Chin C-Y, Yang A-S. Chan D-C, Liu S-H, Chiang C-K Preventing muscle wasting by osteoporosis drug alendronate in vitro and in myopathy models via sirtuin-3 down-regulation. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018 Jun; 9: 585–602, doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnet N, Bourquin L, Biver E, Douni E, Ferrari S. RANKL inhibition improves muscle strength and insulin sensitivity and restores bone mass. J Clin Invest 2019; 129: 3214–23, doi: 10.1172/JCI1125915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]