Abstract

Background:

The occupational exposure limit for trichloroethylene (TCE) in different countries varies from 1 to 100 ppm as an 8-hr time weighted average (TWA). Many countries currently use 10 ppm as the regulatory standard for occupational exposures, but the biological effects in humans at this level of exposure remain unclear.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional molecular epidemiology study of 80 healthy workers exposed to a wide range of trichloroethylene (TCE) (i.e., 0.4 to 229 ppm) and 96 comparable unexposed controls in China, and previously reported that TCE exposure was associated with multiple candidate biological markers related to immune function and kidney toxicity. Here, we conducted further analyses of all of the 31 biomarkers that we have measured to determine the magnitude and statistical significance of changes in the subgroup of workers (n = 35) exposed to <10 ppm TCE compared to controls.

Results:

Six immune biomarkers (i.e., CD4+ effector memory T cells, sCD27, sCD30, IL-10, IgG, and IgM) were significantly decreased (% difference ranged from −16.0% to −72.1%) and one kidney toxicity marker (KIM-1) was significantly increased (% difference: +52.5%) among workers exposed to < 10 ppm compared with the control group. These associations remained noteworthy after taking into account multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (i.e., FDR<0.20).

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that occupational exposure to TCE below 10 ppm as an 8-hr TWA may alter levels of key markers of immune function and kidney toxicity.

Keywords: trichloroethylene, occupational exposure, biomarker, immune function, kidney toxicity

Introduction

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is an industrial solvent used in degreasing, dry cleaning, and for numerous other medical and industrial processes. It is a common environmental contaminant of drinking water and is present in many EPA Superfund sites. [1] The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recently classified trichloroethylene (TCE) as a Group 1 carcinogen based on its consistent association with kidney cancer and noted that there was limited evidence for an association with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). [2, 3]. Currently, there are a wide range of international occupational TCE exposure standards. [4, 5] The current U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Permissible Exposure Limit is 100 ppm as an 8 hour time-weighted average. Many countries have set the standard as 10 ppm or similar levels (i.e., 9 ppm or 11 ppm), and have started considering even lower concentrations as a permissible standard. [4] For example, in response to new information relating to the health and biologic effects of TCE exposure, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) reduced its threshold limit values (TLVs) (i.e., TLV-TWA (time-weighted average) and TLV-STEL (short-term exposure level)) from 50 ppm and 100 ppm to 10 ppm and 25 ppm, respectively, in 2007. Similarly, the Scientific Committee on Occupational Exposure Limits (SCOEL) in 2009 recommended a time weighted average (TWA) of 10 ppm and a STEL of 30 ppm. A lower value of 6 ppm is currently the occupational exposure limit for Germany and China and 1 ppm for Austria.

We previously conducted a series of analyses within a cross-sectional molecular epidemiology study to evaluate the biologic plausibility of carcinogenicity related to occupational exposure to TCE. [6–10]. We reported significant exposure-response relationships between TCE exposure and levels of various immune (i.e., blood cell counts, cytokines, and immunoglobulins) and kidney toxicity markers. Although we observed significant trends for many of these biomarkers, we did not determine if changes in biomarker levels were present below the most common regulatory standard of 10 ppm. Here, we present new analyses on all immune regulation and kidney function markers that we have measured to date to evaluate the effect of TCE exposure at levels under 10 ppm.

Materials and Methods

Study population and exposure assessment

The design, participants, environmental exposure assessment, and biological sample collection for this study have been described. [6] Briefly, this cross-sectional molecular epidemiological study included 80 workers currently exposed to TCE in six study factories with TCE cleaning operations and 96 unexposed controls from the same geographic area in Guangdong, China. Unexposed controls were frequency-matched to exposed workers by sex and age (± 5 years) and were enrolled from two clothing manufacturing factories, one food production factory, and a hospital that did not use TCE. Workers with a history of cancer, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or a previous occupation with notable exposure to benzene, butadiene, styrene and/or ionizing radiation were excluded. A questionnaire-based interview was administered to all subjects to assess demographics, lifestyle characteristics, and occupational history. The study was approved by institutional review boards at the U.S. National Cancer Institute and the Guangdong National Poison Control Center, China.

Personal air exposure measurements were conducted for all study subjects. Full-shift personal air exposure measurements were taken over a three-week period before blood collection in the factories using 3M organic vapor monitoring (OVM) badges. All samples were analyzed for TCE and a subset (48 from TCE-exposed workers) was analyzed for a panel of organic hydrocarbons including benzene, methylene chloride, perchloroethylene, and epichlorohydrin. OVM samples were also obtained on a subgroup of control workers. Current TCE air levels in part per million (ppm) were based on the arithmetic mean of an average of two to three measurements per subject. Ninety-six percent of workers were exposed to TCE below the current U.S. OSHA Permissible Exposure Limit (100 ppm 8h time-weighted average) and 44% of workers were exposed to TCE below 10 ppm (Supplementary Figure 1).

Assays for molecular markers

Participants provided blood, buccal cell mouth rinse, and post-shift and overnight urine samples and underwent a physical examination. Blood samples were delivered to the laboratory within six hours of collection, where the complete blood count and differential and major lymphocyte subsets were analyzed on the same day. Post-shift urine samples were stored at 4 °C until being processed within 10 h of collection. Samples were centrifuged and 1.4 ml of urine supernatant was then mixed with 0.3 ml freezing buffer (NEPHKIT® Urine Stabilizing Buffer; Argutus Medical) to stabilize proteins for storage and freezing. Samples were subsequently stored at −80°C.

The laboratory methods for the evaluated biomarkers have been described in detail.[6–10] A flow cytometer was used for blood cell counting. Plasma sCD27 and sCD30 were measured in duplicate by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Bender Medsystems, Vienna, Austria). Serum concentrations of IgG, IgM and IgE were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Serum concentrations of IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα were measured using a multiplex high-sensitivity human cytokine Milliplex (Billerica, MA) assay for the BioPlex200 (BioRad, Hercules, CA) platform according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Post-shift spot urine samples were analyzed for creatinine, Alpha-GST, Pi-GST, VEGF, KIM-1 and NAG concentrations. Creatinine was determined by automated Jaffé reaction.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted means and standard deviations are presented for all the immune regulation markers (n=26) and kidney function markers (n=5) that were evaluated for an association with TCE exposure previously. Linear regression models using the natural logarithm (ln) of each end point were used to test for differences between control and exposed workers and to evaluate for an exposure–response across TCE exposure categories using a three-level ordinal variable (i.e., controls, low exposure group (<10 ppm), and high exposure group (≥10 ppm)). For each endpoint, we included the same covariates as in our previous reports [6–10] into each model. The covariates included in the linear regression models were age (continuous), sex, current smoking (yes/no), current alcohol consumption (yes/no), recent infections (flu or respiratory infections in the previous month) and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). The models for urinary biomarkers were additionally adjusted for log-transformed creatinine levels. We selected 10 ppm based on a literature review of standards for occupational exposure to TCE (Supplementary Figure 2). [4, 5, 11–15] As shown in the Supplementary Figure 2, the occupational exposure limit for TCE in different countries or organizations with data available (n=47) varied from 1 to 100 ppm as TWA for 8 hours. While 20 countries or organizations still set a relatively high level as a standard (i.e., ≥25 ppm), as many as 21 countries or organizations including the U.S. – ACGIH and E.U. – SCOEL have suggested or adopted 10 ppm as a standard. The standard 9 ppm or 11 ppm may be the same as 10 ppm considering that there may be deviance due to conversion (i.e., μg/m3 to ppm). Even lower levels than 10 ppm were set as a standard by several countries including Austria (1 ppm), Latvia (2 ppm), Germany (AGS -acceptable cancer risk) (6 ppm) and China (6 ppm).

To account for multiple comparisons, the false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated for the set of p-values from the comparisons between control and the low exposed group (<10 ppm). FDR results less than 0.20 were considered noteworthy. For these significant markers, further analyses including workers with even lower exposure levels (i.e., <6, <5, <4, <3, <2, and <1 ppm) and unexposed controls were also conducted. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Demographic characteristics including age, sex, BMI, current smoking, alcohol status and recent infection were comparable between the unexposed control and exposed subjects (Table 1). The mean TCE exposure among the exposed workers was 22.2 ppm (SD: 35.9; range: 0.4–229) and median was 12 ppm, while TCE exposure was negligible in the control factories. On average, the exposed subjects worked for 2 years in the TCE facilities while unexposed subjects worked for 2.3 years in the control factories (data not shown). Six immune biomarkers (CD4+ effector memory T-cells, sCD27, sCD30, IL-10, IgG, and IgM) were significantly decreased (P<0.05 and FDR<0.20) and levels of one urinary kidney function (KIM-1) marker were significantly increased among workers exposed to <10 ppm compared to the unexposed controls (P<0.05, and FDR<0.20) (Table 2). The % differences in biomarker levels among the low exposed group (<10 ppm) relative to unexposed controls were −19.2% for CD4+ effector memory T-cells, −62.7% for sCD27, −34.9% for sCD30, −72.1% for IL-10, −16.0% for IgG, −35.2% for IgM, and +52.5% for KIM-1. In addition, all of these biomarkers showed a statistically significant exposure-response gradient across controls, < 10 ppm, and ≥ 10 ppm TCE exposure (Table 2). An additional 12 biomarkers showed a significant exposure-response association, but levels were not significantly different among workers exposed to <10 ppm compared to unexposed controls. Also, the magnitude of the changes for these biomarkers were from −22.2% to +24.8% among workers exposed to <10 ppm compared to the unexposed controls.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects

| Controls (n=96) | TCE-exposed workers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=80) | <10 ppm (n=35) | ≥10 ppm (n=45) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 27 (7) | 25 (7) | 23 (5) | 27 (7) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22 (3) | 21 (3) | 21 (3) | 22(3) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 23 (24) | 23 (29) | 13 (37) | 10 (22) |

| Male | 73 (76) | 57 (71) | 22 (63) | 35 (78) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | ||||

| No | 58 (60) | 46 (58) | 20 (57) | 26 (58) |

| Yes | 38 (40) | 34 (42) | 15 (43) | 19 (42) |

| Current alcohol use, n (%) | ||||

| No | 56 (58) | 54 (68) | 23 (66) | 31 (69) |

| Yes | 40 (42) | 26 (32) | 12 (44) | 14 (31) |

| Recent infection, n (%) | ||||

| No | 75 (78) | 65 (81) | 28 (80) | 37 (82) |

| Yes | 21 (22) | 15 (19) | 7 (20) | 8 (18) |

| TCE exposure | ||||

| TCE air level (ppm), mean (SD) | <0.03 | 22.19 (35.94) | 4.51 (2.98) | 35.93 (43.25) |

Table 2.

Levels of biological markers by TCE exposure level

| Variable | Unit | Controls (n=96) | TCE-exposed workers | P trendf | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 ppm (n=35) | ≥10 ppm (n=45) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | % difference | Pa | FDRb | Mean (SD) | % difference |

Pa | |||

| Immune regulatory | ||||||||||

| WBCc | 103 cells/μl blood | 6060.4(1348.3) | 6291.7(1412.8) | 3.8 | 4.1E-01 | 6.0E-01 | 5530.9(1239.9) | −8.7 | 1.8E-02 | 3.8E-02 |

| Granulocytesc | 103 cells/μl blood | 3448.1(944.7) | 3795.4(1117.8) | 10.1 | 7.6E-02 | 2.3E-01 | 3413.8(1005.8) | −1.0 | 7.7E-01 | 9.9E-01 |

| Monocytesc | 103 cells/μl blood | 458.8(179.0) | 449.7(163.7) | −2.0 | 6.7E-01 | 7.7E-01 | 443.1(162.4) | −3.4 | 5.7E-01 | 5.5E-01 |

| Lymphocytesc | 103 cells/μl blood | 2153.5(551.8) | 2046.6(550.9) | −5.0 | 3.5E-01 | 5.9E-01 | 1674.0(440.1) | −22.3 | 8.2E-07 | 1.8E-06 |

| T cellsc | 103 cells/μl blood | 1346.2(376.2) | 1349.2(390.4) | 0.2 | 6.7E-01 | 7.7E-01 | 1127.7(344.9) | −16.2 | 9.3E-04 | 1.6E-03 |

| CD4+ T cellsc | 103 cells/μl blood | 675.0(199.6) | 681.0(223.8) | 0.9 | 7.9E-01 | 7.9E-01 | 571.8(185.8) | −15.3 | 3.4E-03 | 5.1E-03 |

| CD4+ naivec | 103 cells/μl blood | 283.2(125.5) | 304.5(143.6) | 7.5 | 7.8E-01 | 7.9E-01 | 231.8(110.8) | −18.1 | 1.2E-02 | 1.5E-02 |

| CD4+ effector memoryc | 103 cells/μl blood | 224.9(92.9) | 181.8(56.7) | −19.2 | 4.2E-02 | 1.9E-01 | 184.5(86.1) | −17.9 | 1.7E-03 | 1.1E-03 |

| CD4CD25c | 103 cells/μl blood | 68.6(35.2) | 79.7(34.1) | 16.3 | 1.2E-01 | 3.3E-01 | 64.4(36.2) | −6.1 | 1.6E-01 | 2.9E-01 |

| CD4CMc | 103 cells/μl blood | 168.6(70.6) | 185.0(74.3) | 9.7 | 5.3E-02 | 2.1E-01 | 168.3(63.7) | −0.2 | 7.7E-01 | 5.7E-01 |

| CD4Foxc | 103 cells/μl blood | 51.7(20.8) | 50.7(26.6) | −1.9 | 5.1E-01 | 6.5E-01 | 48.6(25.9) | −6.0 | 2.4E-01 | 2.2E-01 |

| CD25Foxc | 103 cells/μl blood | 53.1(21.3) | 50.6(25.3) | −4.7 | 4.3E-01 | 6.1E-01 | 49.0(26.3) | −7.9 | 1.1E-01 | 1.0E-01 |

| CD8+ T cellsc | 103 cells/μl blood | 543.5(216.0) | 527.4(173.7) | −3.0 | 7.5E-01 | 7.9E-01 | 421.6(146.4) | −22.4 | 3.2E-04 | 6.0E-04 |

| CD8+ naivec | 103 cells/μl blood | 209.9(103.6) | 220.5(101.2) | 5.1 | 2.9E-01 | 5.6E-01 | 150.3(90.8) | −28.4 | 9.6E-06 | 1.4E-05 |

| CD8EMc | 103 cells/μl blood | 149.5(72.2) | 147.2(69.2) | −1.6 | 5.1E-01 | 6.5E-01 | 121.4(54.4) | −18.8 | 3.2E-02 | 5.5E-02 |

| CD8CMc | 103 cells/μl blood | 8.5(7.5) | 7.9(5.5) | −7.5 | 3.3E-01 | 5.9E-01 | 8.7(11.3) | 2.2 | 8.1E-01 | 9.4E-01 |

| B cellsc | 103 cells/μl blood | 220.9(132.0) | 197.6(103.6) | −10.6 | 3.6E-01 | 5.9E-01 | 157.3(67.4) | −28.8 | 2.6E-03 | 2.9E-03 |

| NK cellsc | 103 cells/μl blood | 467.4(278.7) | 363.8(135.5) | −22.2 | 1.9E-01 | 4.6E-01 | 295.0(158.7) | −36.9 | 2.2E-05 | 2.6E-05 |

| sCD27c | ng/ml plasma | 148.8(107.5) | 55.4(21.6) | −62.7 | 1.6E-07 | 5.0E-06 | 59.1(24.5) | −60.3 | 2.3E-09 | 2.3E-10 |

| sCD30c | ng/ml plasma | 28.7(18.8) | 18.7(7.7) | −34.9 | 4.9E-03 | 5.1E-02 | 19.0(7.7) | −33.6 | 2.1E-03 | 8.3E-04 |

| IL-10d | pg/ml serum | 13.8(23.0) | 3.9(4.3) | −72.1 | 3.4E-02 | 1.7E-01 | 4.8(5.1) | −65.5 | 6.8E-03 | 4.2E-03 |

| IL-6d | pg/ml serum | 3.9(4.5) | 4.2(2.8) | 7.8 | 7.3E-02 | 2.3E-01 | 3.4(5.3) | −14.6 | 4.0E-01 | 6.2E-01 |

| TNF-ad | pg/ml serum | 5.4(2.8) | 5.7(2.1) | 4.8 | 1.5E-01 | 3.9E-01 | 5.3(2.2) | −1.7 | 5.7E-01 | 4.2E-01 |

| IgEe | μg/ml serum | 128.8(138.5) | 101.9(93.0) | −20.9 | 4.1E-01 | 6.0E-01 | 121.6(136.6) | −5.6 | 9.8E-01 | 9.7E-01 |

| IgGe | μg/ml serum | 10990.2(2970.5) | 9235.1(1661.6) | −16.0 | 7.6E-03 | 5.9E-02 | 8940.1(2153.2) | −18.7 | 2.2E-04 | 2.0E-04 |

| IgMe | μg/ml serum | 1178.8(815.8) | 764.4(338.1) | −35.2 | 7.7E-04 | 1.2E-02 | 711.9(365.2) | −39.6 | 2.2E-04 | 2.1E-04 |

| Kidney function | ||||||||||

| KIM-1e | ng/l urine | 211.7(159.5) | 322.8(249.4) | 52.5 | 1.1E-02 | 6.8E-02 | 302.2(201.2) | 42.8 | 2.3E-04 | 2.2E-04 |

| NAGe | ng/l urine | 2.5(1.8) | 2.6(1.4) | 5.9 | 5.9E-01 | 7.3E-01 | 2.5(1.8) | 2.6 | 8.8E-01 | 8.9E-01 |

| PiGSTe | ng/l urine | 26.5(20.1) | 33.1(23.6) | 24.8 | 2.4E-01 | 5.0E-01 | 29.7(26.0) | 12.0 | 8.0E-02 | 7.8E-02 |

| VEGFe | ng/l urine | 302.7(352.4) | 238.3(155.5) | −21.3 | 2.2E-01 | 5.0E-01 | 272.5(189.2) | −10.0 | 6.2E-01 | 6.0E-01 |

| AlphaGSTe | ng/l urine | 8.1(6.4) | 8.4(4.9) | 3.7 | 7.3E-01 | 7.9E-01 | 8.2(8.7) | 1.2 | 8.7E-01 | 8.7E-01 |

For each endpoint, the same covariates as in our previous reports were included in each model; Covariates included in the linear models were age (continuous), sex, current smoking (yes/no), current alcohol consumption (yes/no), recent infections (flu or respiratory infections in the previous month) and body mass index (kg/m2, BMI);

false discovery rate;

analyzed for 80 workers and 96 controls;

analyzed for 71 workers and 78 controls;

analyzed for 80 workers and 45 controls;

Trend was determined by using an ordinal variable for TCE exposure. Significant results for the exposure-response relationships and for differences between controls and the low exposure group (<10 ppm) are bolded.

Beta and P value are for quadratic term of continuous TCE variable.

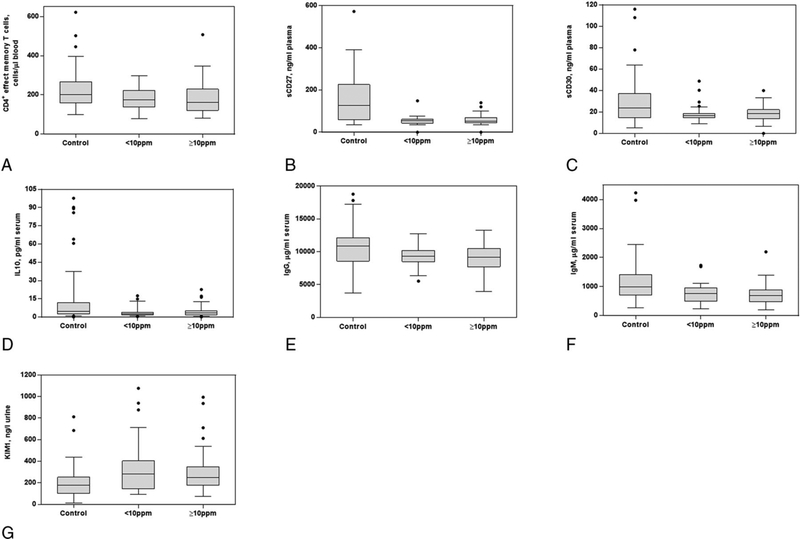

Figure 1 shows boxplots for the seven markers that showed significant differences among the group exposed to < 10 ppm compared with controls. Most of the seven markers except for CD4+ effector memory T-cells showed nonmonotonic exposure-response relationships with the level of TCE. Specifically, the magnitude of differences in levels of these biological markers were comparable in low and high exposed groups relative to the unexposed control workers. In addition, among these seven markers, four (sCD27, IgG, IgM, and KIM-1) remained statistically significant when comparing levels in workers exposed to <6 ppm of TCE to unexposed controls (Supplemental Table 1). Significantly decreased levels of IgM and sCD27 were also observed among the group exposed to <2 ppm and <1 ppm of TCE compared to unexposed controls, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). In general, these seven markers were weakly correlated with each other among both exposed and control workers, except for a higher correlation between sCD27 and sCD30 among controls (rsp = 0.72; Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1. Box plots for selected biomarkers that showed significant differences between controls and those exposed to less than 10 ppm of TCE.

Notes: (a) CD4+ effect memory T cells, (b) sCD27, (c) sCD30, (d) IL10, (e) IgG, (f) IgM, and (g) KIM-1. Most of the box-plots of the nine markers show nonmonotonic dose-response relationships with the level of TCE. Thus, exposure to a much lower level of TCE than 10 ppm may cause significant effects on the level of these biomarker.

Discussion

Six immune regulation markers (i.e., CD4+ effect memory T-cells, sCD27, sCD30, IL-10, IgG, and IgM), and one kidney function marker (KIM-1) were significantly different among those exposed < 10 ppm compared with unexposed controls. Of these markers, sCD27, IgG, IgM, and KIM-1 remained significant at exposure levels even lower at <6ppm and sCD27 and IgM were significant at levels below 2 ppm. These results suggest that biological markers related to immune function and kidney toxicity are altered by low levels of occupational exposure to TCE (i.e., less than 10 ppm or even lower than 6 ppm), below most current national occupational exposure standards.

A decrease in CD4+ effector memory T cells may lead to a decreased capacity of the body to respond to antigenic-related inflammation. [16] A recent study has reported that TCE altered the expression of ~560 genes in the same effector/memory CD4+ T cells. [17] Both sCD27 and sCD30 are shed by B and T cells at activation and are important co-stimulator molecules in the regulation of the balance between Th1 and Th2 responses. [18–19] IL-10 has been demonstrated to suppress chronic inflammation through apoptotic effects on developing macrophages and mast cells. [20] A recent study has reported that the elevation of IL-10 level may be a kind of pathogenesis indicator in occupational medicamentosa-like dermatitis due to TCE. [21] Both IgG and IgM are involved in a variety of host immunological functions, as increased levels of IgM are produced by B cells following antigen stimulation and function in the primary immune response during an acute infection, after which IgG antibodies are produced to mediate the secondary immune response. [22] KIM-1 is known to be strongly upregulated in injured cells throughout the kidneys. [23] Given that altered immunity, including immunosuppression, is an established risk factor for NHL [24], TCE exposure as low as <10 ppm may be mechanistically associated with NHL through the reduced capacity to respond to antigenic-related inflammation. Additionally, kidney toxicity caused by the exposure to low TCE levels may add to plausibility of the epidemiological findings linking TCE and kidney cancer [25].

Evidence from experimental and epidemiological studies contributed to lowering the standards for occupational exposure to TCE from 100 ppm to 50 ppm, 25 ppm and 10 ppm (Supplementary Figure 2).[4, 5] Although the U.S. OSHA still maintains 100 ppm for regulatory purposes, OHSA in California set a standard of 25 ppm, NIOSH has recommended a standard of 25 ppm, and ACGIH has suggested 10 ppm as the standard. It should be noted that most standards went into place before IARC designated TCE as a Group 1 carcinogen. Given that current occupational standards for TCE in different countries vary considerably from 1 to 100 ppm (i.e., United Kingdom: 100 ppm, Mexico: 100 ppm, Japan-JSOH: 25 ppm, and Russia: 10 ppm), studies to evaluate associations between lower levels of TCE exposure and biological changes are warranted. In this context, we focused on evaluating whether there are significant differences in the levels of molecular biomarkers among the group exposed to < 10 ppm of TCE compared to unexposed controls.

Our findings suggest nonmonotonic exposure-response relationships for most of the markers that showed significant differences between those exposed to <10 ppm of TCE and controls. The levels of several markers with nonmonotonic exposure-response relationships were also altered significantly at even lower levels of TCE (i.e., < 2 ppm), and then tended to plateau as the level of TCE exposure increased. Out of the seven markers, four markers (i.e., sCD27, IgG, IgM, and KIM-1) remained statistically significant when the cut point was reduced at 6 ppm and two markers remained significant when the cut point even below 2 ppm, which suggests the potential for a very low exposure threshold for alterations in these specific markers. On the other hand, for the markers with linear exposure-response relationships with TCE exposure level, whether we could detect significant alterations or not may depend on several factors including how steep the slope is (i.e., effect size), population variation in levels of each marker, and sample size.

Our study may have limitation in that we could not elaborate efficiently on the effect of long time exposure and short time exposure due to cross-sectional design. Despite this, when we checked the correlations between work duration and each of the biomarkers, we only found marginally significant negative correlation with VEGF among the exposed subjects. We did further analysis stratified by work duration more than 2 years and less than 2 years. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, consistent trend of the end points between the two strata were observed. As another sensitivity analysis, we conducted Spearman correlation analyses between the covariates and each of the biomarkers, As shown in the Supplementary Table 4, we could find only two noteworthy findings; age was moderately correlated with decreased CD4+ naïve and CD8+ naïve cells, which is consistent with the function of naïve T cells taking center stage on immune aging [26]), and there was a moderate positive correlation between VEGF and gender, which supports the findings of a previous study [27] that VEGF production according to VEGF 936C>T genotype might differ between men and women. However, main results may remain unchanged considering that covariates were already adjusted in the statistical model in our study.

In conclusion, our study suggests that even at levels of exposure below typical regulatory limits (i.e. 10 ppm), certain biomarkers related to immune function and kidney toxicity may be altered by occupational exposure to TCE. Our results contribute to the scientific evidence of biologic changes experienced by workers who are exposed to relatively low level of TCE and raises a question about whether any occupational exposure to TCE can be considered ‘safe’. Continued efforts are warranted to investigate the biologic effects and health outcomes at low levels of exposure to TCE.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

TCE is considered by IARC to be a Group I carcinogen based in part on epidemiological studies linking it to kidney cancer, as well as limited evidence that it is also associated with NHL.

The mechanism of action for TCE has not been identified.

Although occupational exposure to TCE has been associated with changes in various immune and renal toxicity biomarkers, these have been observed at relatively high levels of exposure.

There is little evidence about its biologic effects below current occupational standards in most countries.

What are the new findings?

Seven out of 31 immune regulation and kidney function markers that we have previously reported on from a cross-sectional biomarker study of workers exposed to a wide range of TCE were significantly decreased (CD4+ effector memory T cells, sCD27, sCD30, IL-10, IgG, and IgM) or increased (KIM-1) among workers exposed to < 10 ppm TCE, which is below the current occupational standard in many countries.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our results suggest that occupational exposure to TCE below existing occupational standards may alter levels of key markers of immune function and kidney toxicity and raise additional questions about the safety of current standards.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Support:

Intramural funds from National Institutes of Health and National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P42ES04705 and P30ES01896 to M.T.S.); Northern California Center for Occupational and Environmental Health and Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province, China (2007A050100004 to X.T.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. Trichloroethylene toxicity: Where is trichloroethylene found? (https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=15&po=5) (accessed on 10 Nov 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs 106: Trichloroetheylene, tetrachloroethylene, and some other chlorinated agents. Lyon, France: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guha N, Loomis D, Grosse Y, et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, some other chlorinated solvents, and their metabolites. Lancet Oncol 2012;13(12):1192–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WorkSafe New Zealand. Workplace exposure standard (WES) review: trichloroethylene. 2017. (https://saferfarms.org.nz/dmsdocument/2473-workplace-exposure-standard-wes-review-trichloroethylene) (accessed on 10 Nov 2018)

- 5.European Commission. Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2004/37/EC on the protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to carcinogens or mutagens at work. 2017.

- 6.Lan Q, Zhang L, Tang X, et al. Occupational exposure to trichloroethylene is associated with a decline in lymphocyte subsets and soluble CD27 and CD30 markers. Carcinogenesis 2010;31(9):1592–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosgood HD 3rd, Zhang L, Tang X, et al. Decreased Numbers of CD4(+) Naive and Effector Memory T Cells, and CD8(+) Naïve T Cells, are Associated with Trichloroethylene Exposure. Front Oncol 2012;10;1:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Bassig BA, Mora JL, et al. Alterations in serum immunoglobulin levels in workers occupationally exposed to trichloroethylene. Carcinogenesis 2013;34(4):799–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeulen R, Zhang L, Spierenburg A, et al. Elevated urinary levels of kidney injury molecule-1 among Chinese factory workers exposed to trichloroethylene. Carcinogenesis 2012;33(8):1538–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassig BA, Zhang L, Tang X, et al. Occupational exposure to trichloroethylene and serum concentrations of IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-alpha. Environ Mol Mutagen 2013;54(6):450–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institut fur Arbeitsschutz der Deutschen Gesetzlichen Unfallversicherung. GESTIS International Limit Values: Trichloroethylene. (http://limitvalue.ifa.dguv.de/) (accessed on 26 Oct 2018)

- 12.Fisher Scientific. Safety Data Sheet: trichloroethylene. 2016(https://www.fishersci.com/store/msds?partNumber=T3414&productDescription=TRICHLOROETHYLENE+CR+ACS+4L&vendorId=VN00033897&countryCode=US&language=en) (accessed 10 Nov 2018)

- 13.National Toxicology Program. Report on carcinogens background document for trichloroethylene. 2000. (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8e22/7ba385f9845135d32a83cb698f2c02d6f5b6.pdf?_ga=2.53884008.1990333919.1541785450-1766031430.1541785450) (accessed 10 Nov 2018)

- 14.Acros Organics. Safety Data Sheet: trichloroethylene. 2016. (https://www.binghamton.edu/nano/documents/acetone.pdf) (accessed 10 Nov 2018)

- 15.Axiall. Safety Data Sheet: trichloroethylene. 2013. (http://rossislandsds.co/MasterList%20SDS/PPG%20Industries%20-%20Trichloroethylene%20Degreasing%20and%20General%20Solvent%20%20TRI145%20-%20SDS.pdf) (accessed 10 Nov 2018)

- 16.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, et al. Pillars article: two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. J Immunol 2014;192(3):840–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert KM, Blossom SJ, Reisfeld B, Erickson SW, Vyas K, Maher M, Broadfoot B, West K, Bai S, Cooney CA, Bhattacharyya S. Trichloroethylene-induced alterations in DNA methylation were enriched in polycomb protein binding sites in effector/memory CD4+ T cells. Environ Epigenet. 2017;3(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nolte MA, van Olffen RW, van Gisbergen KP, et al. Timing and tuning of CD27-CD70 interactions: the impact of signal strength in setting the balance between adaptive responses and immunopathology. Immunol Rev 2009;229(1):216–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellegrini P, Berghella AM, Contasta I, et al. CD30 antigen: not a physiological marker for TH2 cells but an important costimulator molecule in the regulation of the balance between TH1/TH2 response. Transpl Immunol 2003;12(1):49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey DP, Kashyap M, Bouton LA, et al. Interleukin-10 induces apoptosis in developing mast cells and macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(3):581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 20 Schroeder HW Jr, Cavacini L. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xueqin Y, Wenxue L, Peimao L, Wen Z, Xianqing H, Zhixiong Z. Cytokine expression and cytokine-based T-cell profiling in occupational medicamentosa-like dermatitis due to trichloroethylene. Toxicol Lett. 2018;288:129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder HW Jr, Cavacini L. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichimura T, Bonventre JV, Bailly V, et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up-regulated in renal cells after injury. J Biol Chem 1998;273(7):4135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ducloux D, Carron PL, Motte G, et al. Lymphocyte subsets and assessment of cancer risk in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int 2002;15(8):393–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L, Zhang J, Li N, Xie H, Chen S, Wang H, Shen T, Zhu QX. Bradykinin receptor in immune-mediated renal tubular injury in trichloroethylene-sensitized mice: Impact on NF-κB signaling pathway. J Immunotoxicol. 2018;15(1):126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae SJ, Ahn DH, Hong SP, Kang H, Hwang SG, Oh D, Kim NK. Gender-specific association between polymorphism of vascular endothelial growth factor(VEGF 936C>T) gene and patients with stomach cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2008. October 31;49(5):783–91. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.5.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goronzy JJ, Fang F, Cavanagh MM, Qi Q, Weyand CM. Naive T cell maintenance and function in human aging. J Immunol. 2015. May 1;194(9):4073–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.