Abstract

Background:

First degree relatives (FDRs) of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients are at risk for CRC, but may not be up to date with CRC screening. We sought to determine if a one-time recommendation about needing CRC screening using patient navigation (PN) was better than just receiving the recommendation only.

Methods:

Participants were FDRs of Lynch syndrome negative CRC patients from participating Ohio hospitals. FDRs from 259 families were randomized to a website intervention (528 individuals), which included a survey and personal CRC screening recommendation, while those from 254 families were randomized to the website plus telephonic PN intervention (515 individuals). Primary outcome was adherence to the personal screening recommendation (to get screened or not to get screened) received from the website. Secondary outcomes examined who benefited from adding PN.

Results:

At the end of the 14-month follow-up, 78.6% of participants were adherent to their recommendation for CRC screening with adherence similar between arms (p=0.14). Among those who received a recommendation to have a colonoscopy immediately, the website plus PN intervention significantly increased the odds of receiving screening, compared to the website intervention (OR: 2.98, 95% CI: (1.68, 5.28).

Conclusions:

Addition of PN to a website intervention did not improve adherence to a CRC screening recommendation overall, however, the addition of PN was more effective in increasing adherence among FDRs who needed screening immediately.

Impact:

These findings provide important information as to when the additional costs of PN are needed to assure CRC screening among those at high risk for CRC.

Keywords: patient navigation, comparative effectiveness, screening interventions, family history, colorectal cancer screening

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common type of cancer and second leading cause of cancer-related death among men and women in the United States (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/index.htm). The best way to prevent CRC is adherence to screenings, such as colonoscopy, which can detect and remove pre-cancerous lesions prior to cancer development (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/index.htm). According to the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an individual at average-risk for CRC is considered within guidelines for CRC screening if they receive either fecal occult blood test (FOBT)/fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years beginning at age 50 (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2). Current Healthy People 2020 objectives aim for 70.5% of adults between the ages of 50–75 years be within CRC screening guidelines by 2020 (https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/cancer/objectives). However, results from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) indicate that 25.6% of U.S adults aged 50–75 years have never been screened for CRC, and only 67.3% are within CRC screening guidelines (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/pdf/QuickFacts-BRFSS-2016-CRC-Screening-508.pdf).

A risk factor for CRC is family history, as individuals with a first-degree relative (FDR) diagnosed with CRC are 2–3 times more likely to develop CRC than individuals without a family history (1). At the time this study was planned, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommended that individuals who had a FDR diagnosed with CRC <50 years of age or had two FDRs with CRC at any age begin colonoscopy at age 40 (or 10 years before the youngest age at diagnosis of CRC among FDRs) and repeat screening every 5 years, if negative (2).

Despite being at increased risk for CRC due to positive family history, FDRs are not always screened according to guidelines (3). One study found that 40% of individuals with a family history of CRC were screened appropriately according to the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines (4). Other research suggests that 47% of individuals at increased risk for CRC (defined as an FDR diagnosed before the age of 55 or two relatives diagnosed with CRC) adhered to CRC screening guidelines (3). Results of these studies indicate an opportunity to increase screening adherence among FDRs of CRC patients.

Previous interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in increasing adherence to CRC screening among CRC patients and/or FDRs. Prior interventions have used mailed print materials demonstrating the importance of CRC screening with or without telephone counseling (5–8). These interventions reported increased CRC screening among individuals who received tailored print or telephone interventions (5,6,8–12). Patient navigation (PN) is an established intervention for promoting cancer screening (13–16), however there are costs associated with PN over non-person intensive interventions like printed material (17). Moreover, not all patients need or use PN when offered (18,19). Newer interventions using web-based technology (20–23) also show promise for delivering education about the need for screening at lower cost (24). PN has only been tested in one study among FDRs of CRC patients to improve CRC screening (8), but not with a website delivering a personalized prescription for screening. We assessed the comparative effectiveness of a website only intervention or website plus PN intervention on adherence to CRC screening among FDRs of CRC patients in Ohio. If PN does not add any benefit to improve CRC screening in this high risk population, then the cheaper option could be easily implemented. It is also important to understand who benefits from the addition of PN in terms of improved CRC screening.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Setting and Enrollment

The Adherence to Colorectal Cancer Screening (ACCS) study is part of the larger Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative (OCCPI). The OCCPI was established to decrease CRC incidence in Ohio by identifying patients with hereditary predisposition (statewide Universal Screening for Lynch syndrome [USLS study], increasing colonoscopy adherence for FDRs of patients with CRC (ACCS study) and encouraging future research through the creation of a biorepository). Ohio was an ideal site for the OCCPI as it has higher incidence and mortality from CRC compared to national rates (www.cdc.gov/uscs). Methods for the overall OCCPI study have been published (25) and are only briefly described here. Participants for the ACCS study were identified through the OCCPI as follows.

Patients diagnosed with CRC (probands) at one of 51 participating hospitals in Ohio from 2013–2016 were eligible to be recruited to the USLS study. CRC patients in the USLS study all received tumor screening for Lynch syndrome (LS), and follow-up genetic testing if they met certain criteria (abnormal tumor screening, diagnosed <50, FDR with CRC or endometrial cancer (EC), or had synchronous or metasynchronous CRC or EC). Probands and their FDRs were excluded from ACCS if they were not between the ages of 25–75 years, were pregnant, incarcerated, cognitively impaired, or had been diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, colitis or any hereditary cancer syndrome. Due to different screening recommendations for CRC patients and their FDRs with LS versus those without LS (2), only FDRs of CRC patients in USLS who screened negative for LS and participated in ACCS are included in the current report.

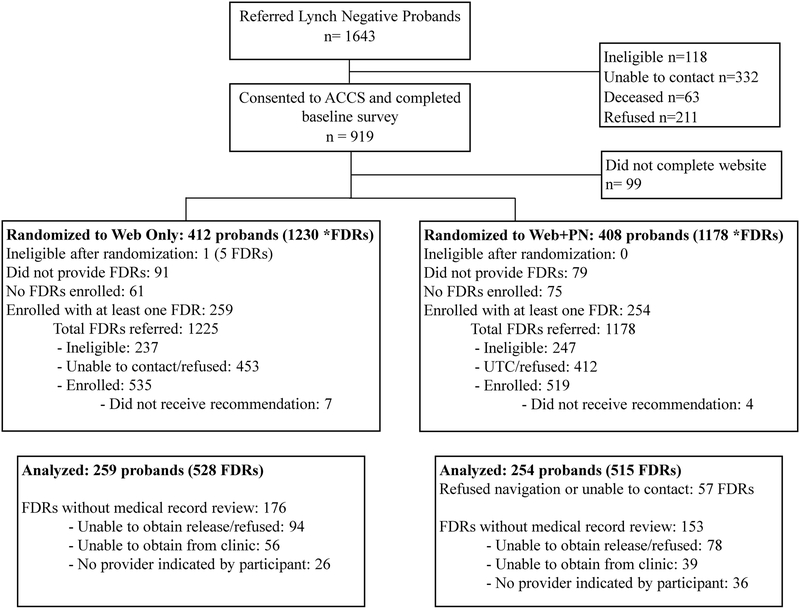

Participants were enrolled in ACCS from 2013–2017, and the last exit interview for participants was completed in January 2018. The trial was completed as planned after the 5 year time period for study collection had ended. A total of 1,643 CRC patients (probands) were referred to the study from the USLS arm (Figure 1), of which 919 (56%) consented to participate in ACCS and completed the baseline survey. A total of 513 probands were enrolled who provided at least one FDR. (Figure 1). These probands referred a total of 2,403 FDRs, of which 484 were ineligible and 865 were unable to be contacted or refused, leaving 1,054 eligible FDRs (55% of total eligible) who consented to participate in ACCS. Ten FDRs did not receive a recommendation via the website due to incomplete data provided, and one FDR received an incorrect message due to an error in the recording of age. These 11 participants were eliminated from the analyses, leaving 1,043 FDRs across 513 unique families. There was very low risk for harm in this intervention and no adverse events were reported. This study was conducted in accordance with the criteria set by the declaration of Helsinki and each participant provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ohio State University (OSU) Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and inclusion of participants in the Adherence to Colorectal Cancer Screening (ACCS) trial.

*FDR: First Degree Relative

Randomization

A nested cohort group-randomized trial (GRT) design was utilized with the unit of randomization being the proband and their FDRs. This design was used to eliminate contamination of the intervention effect within families by assigning participants who were members of the same family to the same study arm. Families were randomized 1:1 to either the website intervention or website plus PN intervention. Of 513 families, 259 families (528 FDRs) were randomized to the website intervention arm while 254 families (515 FDRs) were randomized to the website plus PN intervention arm. Randomization was also stratified by hospital and utilized a permuted block randomization scheme with block sizes of two and four. A centralized web-based system at the OSU was used for all randomization assignments. Whereas patients and study staff allocating participants to each study group were aware of the study arm, outcome assessors and investigators were kept blinded to the allocation.

Website Intervention

All participants received a call from study staff for consent and to complete a baseline survey. Following this, they received a link to a website that collected demographic characteristics and health-related characteristics (e.g., CRC screening history, personal cancer history, and family history of cancer). If a participant did not have internet access, an appointment was scheduled to complete the web questions over the phone with study interviewers. If the participant preferred that interview staff provide assistance, they could complete the website questions while on the baseline call. If unreachable by phone, participants were sent a letter asking them to contact the ACCS via a toll-free phone number.

Following completion of the web survey, a personal CRC screening recommendation document was generated that indicated when a colonoscopy was due (at the present time or later), based on the NCCN guidelines version 2.2012 (2) . The personal screening recommendation was based on participant’s age, the age of the youngest CRC diagnosis among FDRs, history of most recent CRC screening, and personal history of CRC, all based on information in the database about both the proband (age at diagnosis) and the FDR (from the web survey). The recommendation document also included suggestions for healthy behaviors, such as a healthy diet, sufficient sleep, daily exercise, smoking cessation and a recommendation to talk to family members about the importance of CRC screening. The recommendation linked to information regarding CRC from websites such as the National Cancer Institute, the American Cancer Society and the American Gastroenterological Association, and participants were urged to share the recommendation with their primary care provider. Participants could access the recommendation document online and/or have it mailed/emailed to them.

Website plus Patient Navigation Intervention

In addition to the website, participants assigned to the combined intervention also received access to telephonic PN. Navigators addressed individual barriers to adhering to the personal recommendation, as is the process of PN (26). Navigators called participants one month after the receipt of the website recommendation to assess barriers to screening, provide counseling to remove these barriers, and assist participants with scheduling issues for those who needed a colonoscopy. Navigators encouraged participants to talk to their doctor about scheduling a colonoscopy. Following this initial call, navigators periodically followed-up with participants to check on the status of screening and to provide additional assistance and support as needed. For participants whose personal recommendation did not recommend immediate CRC screening, on the initial call, navigators suggested discussing results with their doctor and reminded participants of the importance of being screened and completing screenings according to the NCCN guidelines. If participants did not visit the website within one month of completing the baseline survey, a navigator called the participant to follow-up, regardless of need for screening. Overall, navigators provided follow-up calls based on each participants barriers and needs, as is customary (26).

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was adherence to the personal recommendation received from the website (where CRC screening was either recommended at the present time or no screening was recommended at the present time) over the 14 month follow-up period for each participant. This time period was used to allow time to complete the screening, given lag time in scheduling. For participants who were within the recommended CRC screening guidelines at the time of website completion, adherence was defined as receiving no further screening in the 14 months follow-up period. For participants not within guidelines at the time of website completion, adherence was defined as receiving a colonoscopy within the 14 months follow-up period. All other participants were classified as non-adherent. Other screening tests, including FOBT or FIT, were not considered as appropriate because NCCN recommended colonoscopy for those with a family history of CRC (2). The outcome was determined by medical record review (MRR), which was obtained on 71.7% of participants, however as described below, multiple imputation was used to impute missing outcome data to allow for inclusion of all participants in the analysis. The primary reasons for missing MRR were refusal to sign the MRR release (n=172) and clinic non-compliance with the request (n=95).

Statistical Analyses

Evaluation of the primary outcome of adherence to the personal recommendation regarding CRC screening (to get a colonoscopy at the present time vs a test not needed) by 14 months used a generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach with empirical sandwich variance estimators (27). For the sample size calculation, we assumed an intra-class correlation (ICC) of 0.1 and 4 FDRs per proband, requiring 3,880 families to detect a 2.5% change in the outcome with 83% power (alpha= 0.05). For the analysis, a compound symmetry covariance structure was used, blocked by family. A fully conditional specification method was used to impute the outcome and all covariates considered for analysis. A total of 45 imputations were generated using SAS PROC MI, and results were combined using PROC MIANANLYZE. The initial analysis of the primary outcome included study arm as the only predictor. Subsequent multivariable analyses explored factors that modified or confounded the effect of the addition of PN in an effort to determine who might have benefited from PN. Potential factors included the interaction between study arm and whether the personal recommendation indicated that the participant was due for a colonoscopy at the present time, as well as covariates that resulted in a 15% or greater change in the observed intervention effect. All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. A majority of the participants were female (56.7%), white (94.8%), and married or living with a partner (74.8%). Nearly all (95.2%) had some form of health insurance, and most participants (92.0%) were either children or siblings of the proband. Over two-thirds of participants reported that their risk for developing CRC was either average, below average or much below average in comparison to other individuals of the same age and race. Personal recommendations indicated that 772 participants (74.0%) did not need to have an immediate colonoscopy, while 271 (26.0%) received a recommendation for a colonoscopy at the present time. Among those who did not need to have a colonoscopy at the present time, 351 (45.5%) were too young based on screening guidelines, and 421 (54.5%) had had a recent colonoscopy and did not need one at the present time. A slight majority of participants (56.4%) elected to complete the website questionnaire over the phone at the initial contact as opposed to completing it themselves later. The observed ICC was 0.08.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants by Study Arm*

| Variable | Website only (n=528) N (%) |

Website + PN (n=515) N (%) |

Total (n=1043) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean (SD)*] | 51.4 (12.8) | 52.1 (13.6) | 51.7 (13.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 262 (49.6) | 190 (36.9) | 452 (43.3) |

| Female | 266 (50.4) | 325 (63.1) | 591 (56.7) |

| Race | |||

| White | 489 (92.6) | 500 (97.1) | 989 (94.8) |

| Black | 23 (4.4) | 7 (1.4) | 30 (2.9) |

| Other | 16 (3.0) | 8 (1.6) | 24 (2.3) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married or living with a partner | 400 (75.8) | 379 (73.7) | 779 (74.8) |

| Divorced or Widowed | 78 (14.8) | 75 (14.6) | 153 (14.7) |

| Never Married | 50 (9.5) | 60 (11.7) | 110 (10.6) |

| Insurance Status | |||

| Not Insured | 24 (4.6) | 26 (5.1) | 50 (4.8) |

| Public Insurance | 124 (23.6) | 136 (26.6) | 260 (25.1) |

| Private Insurance | 378 (71.9) | 349 (68.3) | 727 (70.1) |

| Household Income | |||

| <$40k | 101 (20.0) | 99 (20.6) | 200 (20.3) |

| $40k–$79,999k | 173 (34.3) | 149 (31.0) | 322 (32.7) |

| $80k+ | 231 (45.7) | 233 (48.4) | 464 (47.1) |

| Employment Status | |||

| Work Full or Part-time | 371 (70.3) | 331 (64.3) | 702 (67.3) |

| Unemployed/Disabled/Student | 64 (12.1) | 69 (13.4) | 133 (12.8) |

| Retired | 93 (17.6) | 115 (22.3) | 208 (19.9) |

| Educational Attainment | |||

| High School or Less | 139 (26.3) | 150 (29.1) | 289 (27.7) |

| Some College | 151 (28.6) | 121 (23.5) | 272 (26.1) |

| College degree or higher | 238 (45.1) | 244 (47.4) | 482 (46.2) |

| Relationship to Proband | |||

| Parent | 263 (49.8) | 229 (44.5) | 492 (47.2) |

| Sibling | 233 (44.1) | 234 (45.4) | 467 (44.8) |

| Child | 32 (6.1) | 52 (10.1) | 84 (8.1) |

| Perceived likelihood of getting CRC§ in a lifetime | |||

| Unlikely or Very Unlikely | 174 (33.0) | 176 (34.3) | 350 (33.7) |

| 50/50 chance | 277 (52.6) | 274 (53.4) | 551 (53.0) |

| Likely or Very Likely | 76 (14.4) | 63 (12.3) | 139 (13.4) |

| Perceived likelihood of getting CRC§ compared to others | |||

| Below or Much Below Average | 106 (20.1) | 103 (20.1) | 209 (20.1) |

| Average | 242 (45.9) | 252 (49.1) | 494 (47.5) |

| Above or Much Above Average | 179 (34.0) | 158 (30.8) | 337 (32.4) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 77 (14.6) | 80 (15.5) | 157 (15.1) |

| Former | 157 (29.7) | 149 (28.9) | 306 (29.3) |

| Never | 294 (55.7) | 286 (55.5) | 580 (55.6) |

Descriptive statistics from complete case analyses.

SD=standard deviation;

CRC= Colorectal Cancer

Overall, 588 participants (78.6%) were classified as adherent to the recommendation received from the website. Adherence was similar between participants in the website intervention arm and those in the website plus PN intervention arm [77.0% vs. 80.2%; OR 1.27, 95% CI (0.92, 1.75), p=0.14]. Of the 575 participants with completed MRR who received a personal recommendation indicating they did not need to have a colonoscopy, 10.3% (n=59) had a colonoscopy. The reason for possible over-screening was available for 48 participants, of which 33 (68.8%) reported that their doctor recommended the screening.

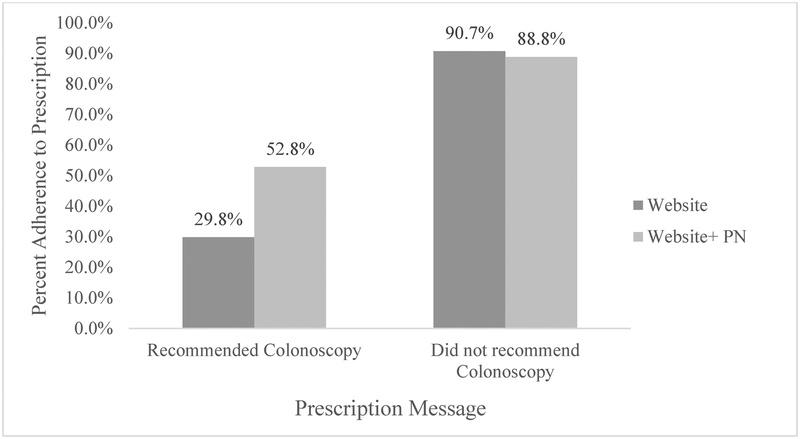

In an effort to determine who benefited from the addition of PN, we explored whether there was a differential effect by study arm and the personal screening recommendation received. Among participants with complete MRR who received a recommendation to not get a colonoscopy, adherence was similar across study arms (90.7% in the website intervention arm vs. 88.8% in the website plus PN intervention arm). However, there was much greater difference for participants who received a recommendation to get a colonoscopy, as 29.8% of those in the website intervention arm were classified as adherent compared to 52.8% of those in the website plus PN intervention arm (see Figure 2). Results from a GEE model using the multiple imputations that included effects for study arm, the recommendation received and the interaction of the two indicated a significant interaction effect (p=0.0006). Model-estimated ORs showed a similar pattern to the complete case analysis with an OR of 0.79 [95% CI: (0.47, 1.33), p=0.37] for website plus PN intervention vs. website intervention among those not recommended to receive a colonoscopy at the present time and an OR of 2.98 [95% CI: (1.68, 5.28), p=0.0002] among those with a recommendation for a colonoscopy at the present time. No additional interactions or confounders were identified.

Figure 2.

The proportion of participants who were adherent to the screening recommendation, by intervention arm (website alone or website plus patient navigation).

In assessing intervention fidelity, all participants received a personalized screening recommendation from the website (either to be screened or not to be screened immediately). Of those randomized to the website plus PN intervention, 88.9% (n=458) spoke with the navigator (8 refused and 49 were unable to be contacted by the navigator). Of those who spoke with the navigator, 45.0% (n=206) received resources from the navigator (fact sheets, booklets, web links). Most participants (74.8%) had only one encounter with the navigator (maximum: 10); however, the majority of those who needed a colonoscopy had more than one encounter (68.1%) for an average of three encounters.

As is typical with PN, barriers to adherence to the recommendation were assessed and then the navigator addressed each barrier listed. Most participants did not report a barrier to following the screening recommendation (77.7%), while 16.4% reported 1–3 barriers and 5.9% reported four or more barriers (range: 0–8). The most commonly reported barriers to screening were: not a priority/too much bother/don’t want to (45.1%), other priorities or health issues (33.3%), not enough time (32.4%), doctor never recommended or received different CRC screening recommendation (24.5%), and not at risk or not necessary due to no problems (23.5%). Navigator response to barriers included support (53%) (encouragement and helping to understand why it is important to get tested, potential outcomes); education (43.2%) (what the tests are, what to expect, what questions to ask); and referral (3.3%) (to providers in the area, what to ask for and help with scheduling).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to improve adherence to personal CRC screening recommendations among FDRs of individuals with CRC. Most importantly, adding PN to the website did not increase adherence to the recommendation in the overall sample. However, the addition of PN to a website intervention was especially effective among participants who received a recommendation for immediate screening, compared to those in the website intervention arm alone. Though prior interventions have had an effect on increased adherence in FDRs (8), the effect in our study was higher, as 52.8% of those who were recommended a colonoscopy in our study received one. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of the ACCS study population were within guidelines for CRC screening, which is somewhat higher than the BRFSS estimates of 67% (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/pdf/QuickFacts-BRFSS-2016-CRC-Screening-508.pdf), suggesting potential limitations for generalizability, as our population of participants may be more likely than others to be within guidelines for screening.

We also observed evidence of possible overuse of CRC screening in this population, as 59 participants received a colonoscopy during the follow-up period although it was not recommended. Prior research suggests that physician recommendation for early follow-up was strongly associated with overuse of CRC screening, a finding in the present study (28,29). Alternatively, this potential over-screening could reflect the change in the NCCN guidelines during our study. At the beginning of this study, guidelines stated that patients who had two FDRs with CRC or one FDR who was diagnosed with CRC ≤60 years of age should start colonoscopy at age 40 or 10 years earlier than the earliest diagnosis of CRC in the family. By the end of the study, recommendations changed such that if any FDR was diagnosed with CRC (regardless of age), FDRs were recommended to start colonoscopy at age 40 or 10 years prior to the youngest diagnosis in the family. Of 59 participants who received screening, though not due, 13 (22%) were younger than age 50 at the time of the recommendation and had an FDR diagnosed with CRC >60 years of age, suggesting that their doctors may have followed the new NCCN guidelines and recommended a colonoscopy even though the personal recommendation suggested otherwise. Another possible reason for both over- and under-screening among our cohort is lack of physician knowledge regarding appropriate CRC screening and surveillance guidelines. A recent study found that while 84–88% of digestive disease specialists reported that they were confident in recalling CRC surveillance and screening guidelines, only 22–37% could accurately identify the factors that determine screening age of onset and surveillance interval and questions involving four clinical vignettes involving screening and surveillance (30).

The main limitation includes the smaller sample size compared to our original recruitment goal. Out of 919 probands that consented to participate in ACCS and completed the baseline survey, 1,054 eligible FDRs were referred and participated. This equated to approximately one FDR per proband rather than the four we estimated. Participants in our study were mostly white, college educated and had health insurance, limiting generalizability of these results to underserved, minority or low socioeconomic populations. Thus, the interventions described in this study should be tested in more diverse populations. For example, other studies have shown the benefit of PN in increasing screening in minority and low income populations (19,31), thus PN might be an ideal way to improve screening in high risk family members in these populations. Moreover, complete MRR was assessed for approximately 70% of FDR participants, suggesting the potential for selection bias if participants for whom we were unable to obtain medical records were somehow different from those for whom we could obtain medical record data. We did, however, use imputation to address missing data.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. The GRT design as well as MRR of colonoscopy screening provided rigor to the study design and reduced the risk of potential bias. Moreover, the use of telephonic PN allowed for consistent and timely implementation of the intervention, i.e., 89% of participants in that arm received a baseline call from the navigator. Further, PN was accessible to large geographic regions for the FDRs, from 34 states across the U.S., plus Washington D.C. Data from our assessment of intervention feasibility collected important information on the actions of the navigator as well as barriers to screening experienced by FDRs. This information is important to those who wish to replicate these interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

Though initial results revealed no benefit with the addition of PN to the website intervention on adherence to screening recommendations (need a colonoscopy now or don’t need one now), subsequent analyses of who benefited from the addition of PN indicated that the addition of telephonic PN to the website was more effective than the website alone on increasing adherence to colonoscopy among FDRs who needed a colonoscopy immediately, potentially reducing future incidence of CRC among those at increased risk.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Funding: The Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative (OCCPI) was supported by internal funds from Pelotonia at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center–James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute (to RP, HH, BB, GY, CT, and JO). The Behavioral Measurement Shared Resource at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA016058), and The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (8UL1TR000090–05).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Trial Registration: , clinicaltrials.gov

References

- 1.Taylor DP, Burt RW, Williams MS, Haug PJ, Cannon-Albright LA. Population-based family history-specific risks for colorectal cancer: a constellation approach. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(3):877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colorectal Cancer Screening Version 2. 2012. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) 2012.

- 3.Courtney RJ, Paul CL, Carey ML, Sanson-Fisher RW, Macrae FA, D’Este C, et al. A population-based cross-sectional study of colorectal cancer screening practices of first-degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin OS, Gluck M, Nguyen M, Koch J, Kozarek RA. Screening patterns in patients with a family history of colorectal cancer often do not adhere to national guidelines. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(7):1841–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glanz K, Steffen AD, Taglialatela LA. Effects of colon cancer risk counseling for first-degree relatives. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(7):1485–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinney AY, Boonyasiriwat W, Walters ST, Pappas LM, Stroup AM, Schwartz MD, et al. Telehealth personalized cancer risk communication to motivate colonoscopy in relatives of patients with colorectal cancer: the family CARE Randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawl SM, Menon U, Burness A, Breslau ES. Interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening: an integrative review. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(4):172–181 e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steffen LE, Boucher KM, Damron BH, Pappas LM, Walters ST, Flores KG, et al. Efficacy of a Telehealth Intervention on Colonoscopy Uptake When Cost Is a Barrier: The Family CARE Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(9):1311–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowery JT, Horick N, Kinney AY, Finkelstein DM, Garrett K, Haile RW, et al. A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(4):601–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowery JT, Marcus A, Kinney A, Bowen D, Finkelstein DM, Horick N, et al. The Family Health Promotion Project (FHPP): design and baseline data from a randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in high risk families. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(2):426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manne SL, Coups EJ, Markowitz A, Meropol NJ, Haller D, Jacobsen PB, et al. A randomized trial of generic versus tailored interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening among intermediate risk siblings. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(2):207–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawl SM, Champion VL, Scott LL, Zhou H, Monahan P, Ding Y, et al. A randomized trial of two print interventions to increase colon cancer screening among first-degree relatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(2):215–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole H, Thompson HS, White M, Browne R, Trinh-Shevrin C, Braithwaite S, et al. Community-Based, Preclinical Patient Navigation for Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Older Black Men Recruited From Barbershops: The MISTER B Trial. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):1433–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeGroff A, Schroy PC 3rd, Morrissey KG, Slotman B, Rohan EA, Bethel J, et al. Patient Navigation for Colonoscopy Completion: Results of an RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3):363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reuland DS, Brenner AT, Hoffman R, McWilliams A, Rhyne RL, Getrich C, et al. Effect of Combined Patient Decision Aid and Patient Navigation vs Usual Care for Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Vulnerable Patient Population: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers RE, Bittner-Fagan H, Daskalakis C, Sifri R, Vernon SW, Cocroft J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored navigation and a standard intervention in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(1):109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall JK, Mbah OM, Ford JG, Phelan-Emrick D, Ahmed S, Bone L, et al. Effect of Patient Navigation on Breast Cancer Screening Among African American Medicare Beneficiaries: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asgary R, Naderi R, Wisnivesky J. Opt-Out Patient Navigation to Improve Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Among Homeless Women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(9):999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freund KM. Implementation of evidence-based patient navigation programs. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halley MC, Rendle KA, Gillespie KA, Stanley KM, Frosch DL. An exploratory mixed-methods crossover study comparing DVD- vs. Web-based patient decision support in three conditions: The importance of patient perspectives. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2880–2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruffin MTt, Fetters MD, Jimbo M. Preference-based electronic decision aid to promote colorectal cancer screening: results of a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruzek SB, Bass SB, Greener J, Wolak C, Gordon TF. Randomized Trial of a Computerized Touch Screen Decision Aid to Increase Acceptance of Colonoscopy Screening in an African American Population with Limited Literacy. Health Commun. 2016;31(10):1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroy PC 3rd, Emmons K, Peters E, Glick JT, Robinson PA, Lydotes MA, et al. The impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(1):93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowen DJ, Robbins R, Bush N, Meischke H, Ludwig A, Wooldridge J. Effects of a web-based intervention on women’s breast health behaviors. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, Zhao W, Yilmaz A, Miller K, et al. Prevalence and Spectrum of Germline Cancer Susceptibility Gene Mutations Among Patients With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunn C, Battaglia TA, Parker VA, Clark JA, Paskett ED, Calhoun E, et al. What Makes Patient Navigation Most Effective: Defining Useful Tasks and Networks. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(2):663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang KZS. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruse GR, Khan SM, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ, Sequist TD. Overuse of colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy CC, Sandler RS, Grubber JM, Johnson MR, Fisher DA. Underuse and Overuse of Colonoscopy for Repeat Screening and Surveillance in the Veterans Health Administration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(3):436–444 e431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patell R, Karwa A, Lopez R, Burke CA. Poor Knowledge of Colorectal Cancer Screening and Surveillance Guidelines in a National Cohort of Digestive Disease Specialists. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernardo BM, Zhang X, Beverly Hery CM, Meadows RJ, Paskett ED. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation programs across the cancer continuum: A systematic review. Cancer. 2019;125(16):2747–2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]