Abstract

Background

Alpha-fetoprotein, cancer antigens 15.3, 19.9, 125, carcinoembryonic antigen and alkaline phosphatase are widely measured in attempts to detect cancer and to monitor treatment response. However, due to lack of sensitivity and specificity, their utility is debated. The serum levels of these markers are affected by a number of non-malignant factors, including genotype. Thus, it may be possible to improve both sensitivity and specificity by adjusting test results for genetic effects.

Methods

We performed genome-wide association studies of serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (N = 22,686), carcinoembryonic antigen (N = 22,309), cancer antigens 15.3 (N = 7,107), 19.9 (N = 9,945) and 125 (N = 9,824), and alkaline phosphatase (N = 162,774). We also examined the correlations between levels of these biomarkers and the presence of cancer, using data from a nation-wide cancer registry.

Results

We report a total of 84 associations of 79 sequence variants with levels of the six biomarkers, explaining between 2.3 and 42.3% of the phenotypic variance. Among the 79 variants, 22 are cis (in- or near the gene encoding the biomarker), 18 have minor allele frequency less than 1%, 31 are coding variants and 7 are associated with gene expression in whole blood. We also find multiple conditions associated with higher biomarker levels.

Conclusions

Our results provide insights into the genetic contribution to diversity in concentration of tumor biomarkers in blood.

Impact

Genetic correction of biomarker values could improve prediction algorithms and decision-making based on these biomarkers.

Keywords: Genome-wide association study, Cancer Antigens, Biomarkers, Alkaline phosphatase, Alpha-fetoprotein, Cancer Antigen 15.3, Cancer Antigen 19.9, Cancer Antigen 125, Carcinoembryonic antigen, Cancer registry

Introduction

Tumor biomarkers are substances or processes that can indicate the presence of cancer [1]. Several tumor biomarkers are in clinical use for monitoring therapy but all lack the sensitivity and specificity to be used for screening. However, recent advances in the detection of circulating tumor DNA suggest that multi-analyte blood tests that combine an assay of somatically mutated DNA (“liquid biopsy”) and protein and carbohydrate biomarkers in serum have the potential to both find early cancer and to help determine its site of origin [2].

In this work, we focused on six commonly measured biomarkers, namely alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigens (CA) 15.3, 19.9 and 125, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Measured in serum, these biomarkers are frequently used to monitor status of disease, response to therapy and recurrence [1]. AFP is used as a biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary and non-seminoma testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT) [3]. CEA has been used as a biomarker for colorectal cancer [4]. CA-15.3 and CA-125 are mainly used as biomarkers of cancers of the breast and ovary, respectively [5, 6], and CA-19.9 is used as a biomarker for pancreatic cancer [7]. We also include ALP in our analysis because its levels are commonly elevated in cancers of the liver and bone and when other cancers metastasize to these tissues [8]. However, the measurement of ALP in serum is one of the most common blood tests ordered and we recognize that there are many reasons for ALP measurements other than suspicion of- or monitoring of neoplasms.

Despite widespread use of these biomarkers in clinical practice, their low sensitivity and specificity continue to cause controversy over their use [9–11]. As their levels are partially determined by genetic factors, one approach to improve their sensitivity and specificity would be to define “normal” values based on age, sex and genotype [2, 9]. We have previously reported how genetic correction for variants affecting levels of prostate specific antigen (PSA) results in personalized PSA cutoff value, which is more informative than a general cutoff value when deciding to perform a prostate biopsy [12].

The main goal of this study is to perform a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of the levels of all six tumor biomarkers to identify sequence variants that affect baseline biomarker levels, regardless of cancer diagnosis. We also describe the associations of the six tumor biomarker levels with various cancer diagnoses, obtained from a nation-wide cancer registry, and for comparison, with four non-neoplastic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Cancer diagnoses, including the date of diagnosis, were extracted from the Icelandic cancer registry (ICR) (http://www.cancerregistry.is), which contains all diagnoses of solid cancers made in in the country from January 1st 1955 to December 31st 2015 [13]. We also assessed four other diseases; inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis, because these diseases are associated with inflammation in the gastrointestinal organs and fibromyalgia, because patients present with diverse symptoms and often undergo measurements for tumor biomarkers as part of a lengthy diagnosis journey. Tumor biomarker measurements were made in Icelandic laboratories from 1990 to 2015 and linked with disease diagnoses on the basis of encrypted social security numbers.

This study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee of Iceland (reference numbers VSNb2006010014/03.12, 06–007-V3 and VSNb201501033/03.12). A further description of subject recruitment, phenotyping, genotyping and imputation is available in the supplementary methods.

Genome wide association study

To identify genetic variants associated with baseline biomarker values, we performed a GWAS of all available data, including both cancer patients and individuals without cancer diagnosis. When multiple measurements of a biomarker were available for a subject, we used the earliest value recorded. We found this approach to be the most powerful as exclusion of cancer patients resulted in great loss of power, for residual associations (secondary, tertiary variants etc) in particular. The first measurement was used as this meant that measurements taken months or years before cancer diagnosis were available for a subset of the cancer patients.

As indicated in Table 1 the biomarkers all show extremely right-skewed distributions. The data contains a number of extreme outliers but no trends were observed to link these with date of measurement, age of the subject or even cancer type (Supplementary figure 1).

Table 1:

Tumor markers and subjects used in this study. AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; CA: Cancer antigen; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase.

| Biomarker | Total subjects | N (% Female) | Measurement unit | Avg. age at first measurement (range) | Median first value (range) | Median largest value (range) | Reference valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP | 22,686 | 12,886 (56.8) | U/ml | 57 (0 – 100) | 3.0 (0.4 – 385,725) | 3.2 (0.4 – 385,725) | <5.8 |

| CA-15.3 | 7,107 | 6,304 (88.7) | U/ml | 62 (1 – 99) | 17.7 (1.0 – 17,340) | 20.8 (1.0 – 47,600) | <25 |

| CA-125 | 9,824 | 9,087 (92.5) | U/ml | 58 (1 – 103) | 16.6 (0.6 – 56,820) | 18.0 (0.6 – 63,062) | <35 |

| CA-19.9 | 9,945 | 5,708 (57.4) | U/ml | 66 (7 – 101) | 16.3 (0.0 – 1,769,950) | 18.9 (0.0 – 16,571,700) | <31 |

| CEA | 22,309 | 13,095 (58.7) | ng/ml | 63 (0 – 103) | 2.3 (0.0 – 63,962) | 2.7 (0.0 – 116,069) | <4.6 |

| ALP | 162,774 | 87,897 (54.0) | U/ml | 46 (0 – 114) | 119.0 (0.0 – 15,825) | 134.0 (5.0 – 21,668) | <105 |

The reference value is that generally considered based on the respective tests used in Landspitali, the National University Hospital in Iceland.

We performed a rank-based inverse normal transformation adjusting for age at measurement and time to death for deceased subjects for each gender separately. Adjustment for time to death was performed as we have observed large changes close to the time of death for many quantitative measurements. In this case, a high biomarker value shortly before death might indicate a high tumor burden. We tested the association between biomarker value and genotype by a generalized form of linear regression. To assess significance of primary associations, we used different P value thresholds depending on the annotation class of the variant as described in Sveinbjornsson et al [14]. We consider loss-of-function variants (frameshifts, stop codon gained/lost, initiator codon variants and splice acceptor/donor variants) significant at 3.6 × 10−7, in-frame insertions/deletions, missense and splice region variants at 7.4 × 10−8, synonymous variants, up/downstream variants, variants that resulted in a stop-codon being retained, and variants in 3’/5’ untranslated regions at 5.3 × 10−9, intronic and intergenic variants within DNase hypersensitivity sites at 3.3 × 10−9 and intergenic and intronic variants outside DNase hypersensitivity sites at 1.1 × 10−9. We used the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) release 80 [15] to annotate variants, considering only protein-coding transcripts from RefSeq release 67 [16].

Loci harboring variants associated by these criteria underwent further analyses to check for the presence of other, independent variants affecting the trait. While any variant passed the significance threshold at a locus, we tested all variants flanking the primary signal by 1–13 Mb, depending on the strength of association and the recombination pattern at the locus, by sequentially adding the top variant from previous steps as covariate in the regression. The use of wide windows was occasionally necessary to avoid spurious associations arising from very low, but not negligible, LD between an extremely significant variant and distant variants. Residual associations were generally close to the primary signal, as can be seen in Tables 2 and 3. We considered significant variants that passed a simple Bonferroni correction for the number of variants in the respective region. This process was repeated, adding the top variant as covariate for the next round until no significant associations remained. The gene expression and co-localization analyses are described in the supplementary methods.

Table 2:

Primary variants within loci associating with tumor biomarker levels.

| rsID | Chromosome: Positiona | MAF [%] | Amin | Amaj | Gene | Annotation | P | PCorrectedb | Effectc | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-fetoprotein | ||||||||||

| rs28929474 | chr14:94378610 | 0.8 | T | C | SERPINA1 | Glu366Lys | 1.2 × 10−47 | 8.3 × 10−42 | −0.85 (−0.96, −0.74) | 0.012 |

| Cancer antigen 15.3 | ||||||||||

| rs760077 | chr1:155208991 | 35.4 | A | T | MTX1 | Ser63Thr | < 1 × 10−300 | < 1 × 10−300 | 0.86 (0.81, 0.90) | 0.34 |

| NA | chr9:133264504 | 19.5 | G | GAAA CTGCC |

ABO | intron | 1.8 × 10−47 | 8.0 × 10−40 | −0.33 (−0.38, −0.29) | 0.035 |

| Cancer antigen 125 | ||||||||||

| rs62193080 | chr2:241800675 | 20.6 | G | C | GAL3ST2 | intron | 2.9 × 10−57 | 1.3 × 10−49 | −0.32 (−0.36, −0.28) | 0.033 |

| rs3764246 | chr16:760143 | 23.6 | G | A | MSLN | upstream | 3.2 × 10−15 | 3.0 × 10−8 | −0.15 (−0.18, −0.11) | 0.008 |

| rs73005873 | chr19:8896954 | 39.7 | A | G | MUC16 | intron | 1.8 × 10−17 | 8.2 × 10−10 | 0.14 (0.11, 0.17) | 0.009 |

| Cancer antigen 19.9 | ||||||||||

| rs708686 | chr19:5840608 | 23.1 | T | C | FUT6 | upstream | 1.9 × 10−179 | 1.8 × 10−172 | −0.52 (−0.56, −0.49) | 0.097 |

| rs601338 | chr19:48703417 | 39.3 | G | A | FUT2 | Trp154Ter | 1.3 × 10−291 | 1.8 × 10−286 | −0.57 (−0.61, −0.54) | 0.16 |

| rs34262244 | chr19:17795098 | 28.5 | A | G | B3GNT3 | upstream | 3.0 × 10−13 | 2.8 × 10−6 | −0.13 (−0.17, −0.10) | 0.0070 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | ||||||||||

| rs7041150 | chr9:106732343 | 37.8 | A | C | — | intergenic | 1.8 × 10−12 | 2.7 × 10−5 | −0.08 (−0.10, −0.06) | 0.0030 |

| rs635634 | chr9:133279427 | 13.0 | T | C | ABO | upstream | 9.4 × 10−16 | 8.8 × 10−9 | −0.13 (−0.16, −0.10) | 0.0039 |

| rs708686 | chr19:5840608 | 23.1 | T | C | FUT6 | upstream | 4.6 × 10−16 | 4.3 × 10−9 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 0.0039 |

| rs9621 | chr19:41727239 | 5.6 | A | G | CEACAM5 | Gly678Arg | 5.2 × 10−201 | 3.5 × 10−195 | 0.71 (0.67, 0.76) | 0.054 |

| rs601338 | chr19:48703417 | 39.3 | G | A | FUT2 | Trp154Ter | 5.1 × 10−130 | 6.9 × 10−125 | −0.27 (−0.29, −0.25) | 0.035 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | ||||||||||

| rs149344982 | chr1:21563267 | 1.5 | A | G | ALPL | Arg75His | 1.4 × 10−157 | 9.5 × 10−146 | −0.46 (−0.49, −0.43) | 0.0061 |

| rs1862069 | chr2:169077231 | 49.6 | A | G | DHRS9 | upstream | 6.1 × 10−10 | 0.0057 | −0.03 | 0.00034 |

| rs1260326 | chr2:27508073 | 34.1 | T | C | GCKR | Leu446Pro | 4.6 × 10−11 | 3.1 × 10−5 | 0.03 | 0.00038 |

| rs573778305 | chr6:24429112 | 0.8 | C | CT | GPLD1 | Frameshift Val815 | 1.8 × 10−111 | 2.4 × 10−106 | −0.53 (−0.58, −0.48) | 0.0042 |

| rs62621812 | chr7:127375029 | 2.5 | A | G | ZNF800 | Pro103Ser | 6.7 × 10−9 | 0.0045 | −0.08 (−0.10, −0.05) | 0.00029 |

| rs6984305 | chr8:9320758 | 8.4 | A | T | — | intergenic | 1.7 × 10−16 | 2.5 × 10−9 | 0.06 (0.05, 0.08) | 0.00057 |

| rs4242592 | chr8:118956736 | 47.9 | T | G | TNFRSF11B | upstream | 2.5 × 10−10 | 0.0023 | −0.03 (−0.03, −0.02) | 0.00034 |

| rs28601761 | chr8:125487789 | 43.0 | G | C | — | intergenic | 4.0 × 10−15 | 1.8 × 10−7 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02) | 0.00053 |

| rs41282145 | chr9:101487225 | 4.3 | A | T | TMEM246 | upstream | 1.4 × 10−14 | 1.3 × 10−7 | 0.08 (0.06, 0.10) | 0.00050 |

| NA | chr9:133264504 | 19.5 | G | GAAA CTGCC |

ABO | intron | < 1 × 10−300 | < 1 × 10−300 | −0.20 (−0.21, −0.19) | 0.013 |

| rs1935 | chr10:63168063 | 47.6 | C | G | JMJD1C | Glu2353Asp | 1.7 × 10−29 | 1.2 × 10−23 | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04) | 0.0011 |

| rs10790256 | chr11:118663373 | 22.2 | T | C | TREH | synonymous | 1.4 × 10−9 | 0.013 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02) | 0.00031 |

| rs10893507 | chr11:126416693 | 48.1 | A | C | ST3GAL4 | downstream | 9.2 × 10−18 | 8.6 × 10−11 | 0.04 (0.03, 0.04) | 0.00065 |

| rs7955258 | chr12:461781 | 44.5 | A | G | B4GALNT3 | intron | 1.3 × 10−14 | 5.9 × 10−7 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02) | 0.00051 |

| rs10849087 | chr12:4540899 | 27.1 | T | C | C12orf4 | upstream | 1.1 × 10−9 | 0.0010 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02) | 0.00031 |

| rs2393791 | chr12:120986153 | 35.4 | C | T | HNF1A | intron | 3.4 × 10−13 | 5.0 × 10−6 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 0.00044 |

| rs9533095 | chr13:42394913 | 43.5 | G | T | — | intergenic | 7.6 × 10−10 | 0.011 | −0.03 (−0.03, −0.02) | 0.00033 |

| rs28929474 | chr14:94378610 | 0.8 | T | C | SERPINA1 | Glu366Lys | 3.4 × 10−17 | 2.3 × 10−11 | 0.20 (0.15, 0.24) | 0.00062 |

| rs2297066 | chr14:103100498 | 21.9 | G | C | EXOC3L4 | Asp93Glu | 7.7 × 10−9 | 0.0052 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 0.00029 |

| rs71391445 | chr16:72171122 | 18.1 | G | GA | PMFBP1 | intron | 4.6 × 10−13 | 6.9 × 10−6 | 0.04 (0.03, 0.05) | 0.00045 |

| rs186021206 | chr17:7166093 | 0.4 | A | G | — | intergenic | 7.3 × 10−89 | 3.3 × 10−81 | 0.63 (0.57, 0.69) | 0.0034 |

| rs5112 | chr19:44927023 | 48.6 | G | C | — | intergenic | 1.7 × 10−16 | 7.7 × 10−9 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.03) | 0.00058 |

| rs8736 | chr19:54173495 | 41.6 | T | C | TMC4 | upstream | 8.1 × 10−16 | 7.6 × 10−9 | 0.03 (0.03, 0.04) | 0.00056 |

| rs2500430 | chr20:25298327 | 49.2 | G | A |

ABHD12 PYGB |

downstream | 6.95 × 10−10 | 0.0065 | −0.03 (−0.03, −0.02) | 0.00034 |

| rs41302559 | chr20:57565383 | 0.9 | A | G | PCK1 | Arg483Gln | 2.90 × 10−8 | 0.020 | −0.12 (−0.17, −0.08) | 0.00026 |

The position is given in hg38

The P-value after a weighted Bonferroni adjustment where a different threshold was used for each functional class (see methods).

Effect of the minor allele (Amin) is reported as standard deviations of rank-based inverse normally transformed data

Table 3:

Residual associations within loci associating with tumor biomarker levels.

| rsID | Chromosome: Positiona | MAF [%] | Amin | Amaj | Gene | Annotation | P | Effect† | PCorrectb | Effectc | R2 | Covariate(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-fetoprotein | ||||||||||||

| rs17580 | chr14:94380925 | 3.3 | A | T | SERPINA1 | Glu288Val | 8.3 × 10−38 | −0.38 (−0.43, −0.32) | 2.3 × 10−33 | −0.38 (−0.43, −0.32) | 0.0091 | rs28929474 |

| rs2402446 | chr14:94399800 | 47.6 | T | A | — | intergenic | 7.5 × 10−9 | 0.06 (0.04, 0.08) | 2.1 × 10−5 | 0.06 (0.04, 0.08) | 0.0020 | rs28929474, rs17580 |

| Cancer antigen 15.3 | ||||||||||||

| rs41264915 | chr1:155197995 | 14.2 | G | A | THBS3 | intron | 2.5 × 10−63 | 0.38 (0.34, 0.43) | 5.8 × 10−59 | 0.38 (0.34, 0.43) | 0.035 | rs760077 |

| rs72704117 | chr1:155205298 | 3.0 | T | C | THBS3 | Arg102Gln | 1.4 × 10−14 | −0.38 (−0.48, −0.28) | 3.2 × 10−10 | −0.38 (−0.48, −0.28) | 0.0083 | rs760077, rs41264915 |

| rs564968560 | chr1:155614403 | 2.0 | A | G | MSTO1 | 3’UTR | 1.4 × 10−11 | −0.37 (−0.48, −0.27) | 3.2 × 10−11 | −0.37 (−0.48, −0.27) | 0.0055 | rs760077, rs41264915 rs72704117 |

| rs822493 | chr1:155855602 | 3.3 | T | C | SYT11 | upstream | 2.5 × 10−8 | 0.25 (0.16, 0.33) | 5.8 × 10−4 | 0.25 (0.16, 0.33) | 0.0038 | rs760077, rs41264915 rs72704117, rs564968560 |

| Cancer antigen 125 | ||||||||||||

| rs141828605 | chr2:241803397 | 0.9 | T | C | GAL3ST2 | Pro143Leu | 9.6 × 10−29 | 0.91 (0.75, 1.07) | 2.7 × 10−24 | 0.91 (0.75, 1.07) | 0.015 | rs62193080 |

| rs150107870 | chr2:241804117 | 1.9 | C | T | GAL3ST2 | Leu383Pro | 2.2 × 10−23 | 0.61 (0.49, 0.73) | 6.2 × 10−19 | 0.61 (0.49, 0.73) | 0.014 | rs62193080, rs141828605 |

| rs139344622 | chr2:241803427 | 0.9 | G | A | GAL3ST2 | Tyr153Cys | 8.4 × 10−16 | 0.68 (0.51, 0.84) | 2.4 × 10−11 | 0.68 (0.51, 0.84) | 0.008 | rs62193080, rs141828605 rs150107870 |

| rs5839764 | chr2:241764203 | 38.6 | G | C | D2HGDH | intron | 2.2 × 10−11 | −0.12 (−0.16, −0.09) | 6.1 × 10−7 | −0.12 (−0.16, −0.09) | 0.007 | rs62193080, rs141828605 rs150107870, rs139344622 |

| rs9927389 | chr16:764058 | 1.5 | T | C | MSLN | Ala72Val | 2.6 × 10−13 | −0.46 (−0.58, −0.34) | 6.7 × 10−9 | −0.46 (−0.58, −0.34) | 0.006 | rs3764246 |

| rs150425699 | chr16:768452 | 0.4 | A | G | MSLN | Arg557His | 4.3 × 10−9 | −0.74 (−0.98, −0.50) | 7.0 × 10−5 | −0.74 (−0.98, −0.50) | 0.005 | rs3764246, rs9927389 |

| Cancer antigen 19.9 | ||||||||||||

| rs2608894 | chr19:5847989 | 17.1 | T | C | FUT3 | intron | 3.7 × 10−10 | −0.21 (−0.27, −0.14) | 1.4 × 10−5 | −0.21 (−0.27, −0.14) | 0.012 | rs708686 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | ||||||||||||

| rs10901252 | chr9:133252613 | 6.5 | C | G | ABO | downstream | 9.4 × 10−8 | 0.12 (0.07, 0.16) | 3.0 × 10−3 | 0.12 (0.07, 0.16) | 0.0017 | rs635634 |

| rs59654817 | chr19:41709489 | 33.4 | A | G | CEACAM5 | intron | 3.8 × 10−20 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 6.3 × 10−15 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 0.0049 | rs9621 |

| rs12985771 | chr19:41725256 | 36.3 | C | A | CEACAM5 | intron | 1.8 × 10−18 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 3.0 × 10−13 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 0.0051 | rs9621, rs59654817 |

| rs770162662 | chr19:41755473 | 0.3 | T | G | CEACAM6 | upstream | 4.5 × 10−10 | 0.63 (0.43, 0.83) | 7.6 × 10−5 | 0.63 (0.43, 0.83) | 0.0026 | rs9621, rs59654817, rs12985771 |

| rs7247317 | chr19:41712945 | 49.0 | T | G | CEACAM5 | intron | 6.9 × 10−9 | 0.10 (0.06, 0.13) | 1.2 × 10−3 | 0.10 (0.06, 0.13) | 0.0046 | rs9621, rs59654817, rs12985771, rs770162662 |

| rs757625335 | chr19:48505357 | 0.3 | A | G | LMTK3 | intron | 7.4 × 10−8 | 0.52 (0.33, 0.71) | 4.2 × 10−3 | 0.52 (0.33, 0.71) | 0.0014 | rs601338 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | ||||||||||||

| rs138587317 | chr1:21563248 | 0.12 | A | G | ALPL | Glu69Lys | 4.3 × 10−110 | −1.12 (−1.22, −1.03) | 4.2 × 10−105 | −1.12 (−1.22, −1.03) | 0.0043 | rs149344982 |

| rs121918007 | chr1:21564139 | 0.06 | A | !A | ALPL | Glu114Lys | 2.8 × 10−51 | −1.27 (−1.43, −1.10) | 2.8 × 10−46 | −1.27 (−1.43, −1.10) | 0.0019 | rs149344982, rs138587317 |

| rs773257111 | chr1:21563143 | 0.01 | A | G | ALPL | Ala34Thr | 6.9 × 10−27 | −2.05 (−2.42, −1.67) | 5.9 × 10−22 | −2.05 (−2.42, −1.67) | 0.0011 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007 |

| rs121918019 | chr1:21564094 | 0.009 | A | G | ALPL | Ala99Thr | 3.6 × 10−12 | −1.54 (−1.98, −1.11) | 3.1 × 10−7 | −1.54 (−1.98, −1.11) | 0.00043 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111 |

| rs4654748 | chr1:21459575 | 43.4 | T | C | NBPF3 | intron | 1.5 × 10−118 | −0.10 (−0.10, −0.09) | 1.3 × 10−113 | −0.10 (−0.10, −0.09) | 0.0045 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111, rs121918019 |

| rs1780329 | chr1:21576457 | 16.5 | A | G | ALPL | intron | 5.9 × 10−52 | −0.08 (−0.09, −0.07) | 5.0 × 10−47 | −0.08 (−0.09, −0.07) | 0.0019 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111, rs121918019, rs4654748 |

| rs11463187 | chr1:21540322 | 21.2 | TG | T | ALPL | intron | 1.4 × 10−35 | −0.07 (−0.08, −0.05) | 1.2 × 10−30 | −0.07 (−0.08, −0.05) | 0.0014 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111, rs121918019, rs4654748, rs1780329 |

| rs115257434 | chr1:21570934 | 2.3 | A | G | ALPL | Intron | 1.9 × 10−20 | −0.14 (−0.16, −0.11) | 1.6 × 10−15 | −0.14 (−0.16, −0.11) | 0.00083 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111, rs121918019, rs4654748, rs1780329, rs11463187 |

| rs1697405 | chr1:21577713 | 40.5 | !C | C | ALPL | 3’ UTR | 2.7 × 10−19 | −0.042 (−0.05, −0.03) | 1.6 × 10−15 | −0.042 (−0.05, −0.03) | 0.00085 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111, rs121918019, rs4654748, rs1780329, rs11463187, rs115257434 |

| rs1318236 | chr1:21625531 | 43.9 | C | T | RAP1GAP | intron | 6.8 × 10−18 | 0.037 ( 0.03, 0.05) | 2.3 × 10−14 | 0.037 ( 0.03, 0.05) | 0.00067 | rs149344982, rs138587317, rs121918007, rs773257111, rs121918019, rs4654748, rs1780329, rs11463187, rs115257434, rs1697405 |

| rs17300770 | chr6:24462792 | 11.6 | C | G | GPLD1 | Asp275Glu | 3.1 × 10−43 | −0.09 (−0.10, −0.08) | 1.5 × 10−37 | −0.09 (−0.10, −0.08) | 0.0016 | rs573778305 |

| rs9467148 | chr6:24435774 | 27.0 | A | G | GPLD1 | intron | 1.8 × 10−29 | 0.05 (0.04, 0.06) | 8.4 × 10−24 | 0.05 (0.04, 0.06) | 0.0011 | rs573778305, rs17300770 |

| rs146221974 | chr6:24473633 | 0.1 | A | G | GPLD1 | Ser159Leu | 9.4 × 10−17 | −0.51 (−0.63, −0.39) | 4.4 × 10−11 | −0.51 (−0.63, −0.39) | 0.00058 | rs573778305, rs17300770, rs9467148 |

| rs116287860 | chr6:24456679 | 8.5 | C | A | GPLD1 | intron | 9.6 × 10−14 | 0.06 ( 0.04, 0.08) | 4.5 × 10−8 | 0.06 ( 0.04, 0.08) | 0.00049 | rs573778305, rs17300770, rs9467148, rs146221974 |

| rs183821586 | chr6:24473963 | 0.1 | G | A | GPLD1 | intron | 3.7 × 10−11 | −0.42 (−0.54, −0.30) | 1.7 × 10−5 | −0.42 (−0.54, −0.30) | 0.00040 | rs573778305, rs17300770, rs9467148, rs146221974, rs116287860 |

| rs6993155 | chr8:125496809 | 4.4 | G | A | — | intergenic | 1.4 × 10−8 | −0.06 (−0.08, −0.04) | 7.9 × 10−4 | −0.06 (−0.08, −0.04) | 0.00028 | rs28601761 |

| rs2183745 | chr9:101456893 | 27.8 | T | A | — | intergenic | 1.4 × 10−10 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 3.8 × 10−6 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 0.00036 | rs41282145 |

| rs56392308 | chr9:133255669 | 6.5 | C | CG | ABO | Frameshift Pro354 | 1.3 × 10−21 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.12) | 4.2 × 10−18 | 0.10 (0.08, 0.12) | 0.0011 | chr9:133264504 |

| rs527478501 | chr11:62072649 | 0.6 | G | A | — | intergenic | 3.8 × 10−8 | 0.14 (0.09, 0.19) | 1.1 × 10−3 | 0.14 (0.09, 0.19) | 0.00026 | rs174564 |

| rs17145892 | chr11:62432797 | 18.8 | T | A | AHNAK | downstream | 2.7 × 10−7 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02) | 8.0 × 10−3 | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02) | 0.00022 | rs174564, rs527478501 |

| rs78689694 | chr11:126364925 | 10.5 | C | G | ST3GAL4 | intron | 1.9 × 10−12 | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.03) | 5.5 × 10−8 | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.03) | 0.00043 | rs10893507 |

| rs200173452 | chr12:552099 | 0.4 | T | C | B4GALNT3 | Arg382Cys | 3.1 × 10−8 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.24) | 9.3 × 10−4 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.24) | 0.00027 | rs7955258 |

| rs77303550 | chr16:72045758 | 18.2 | T | C | — | intergenic | 2.4 × 10−7 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 6.9 × 10−3 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 0.00023 | rs71391445 |

| NA | chr17:7156651 | 17.5 | !AAG AGAA AGAG |

AAGA GAAA GAG |

— | intergenic | 4.0 × 10−8 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 1.5 × 10−3 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 0.00026 | rs186021206, rs55714927 |

| rs55714927 | chr17:7176997 | 21.0 | T | C | ASGR1 | synonymous | 2.6 × 10−48 | 0.07 (0.06, 0.09) | 9.5 × 10−44 | 0.07 (0.06, 0.09) | 0.0019 | rs186021206 |

The position is given in hg38

The corrected P-value is the P-value after Bonferroni correction for the number of variants in the locus.

Effect of the minor allele (Amin) is reported as standard deviations of rank-based inverse normally transformed data

Comparison of biomarkers across diseases

Many of the subjects have undergone several biomarker measurements, prior to, during and/or after being diagnosed with cancer, with most measurements being from a few months before official diagnosis date or later. Other subjects have undergone measurements without being diagnosed with cancer. The latter subjects show a trend for being younger than the cancer patients. Supplementary figure 2 shows the age distribution of each subject group for each biomarker. Some subjects have had more than one type of cancer. In this case, the first diagnosis was used.

We used a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare the highest values of biomarkers recorded for individuals with specific diseases to the highest values of subjects without cancer diagnosis (or diagnosis of any of the other diseases, Figure 2). We considered significant P-values that passed Bonferroni correction for 144 tests (6 biomarkers x 24 disease conditions).

Figure 2:

Biomarker elevation across cancer types.

Figure 2 shows the median of the largest value ever recorded for each individual across cancers and diseases for a) Alpha fetoprotein; b) Cancer antigen 15.3; c) Cancer antigen 125; d) Cancer antigen 19.9; e) Carcinoembryonic antigen; f) Alkaline phosphatase. In each plot, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 10 codes categorize cancers. The ICD-10 code C.80 represents cancers of unknown primary site. These cancers have high metastatic potential as they have spread before the primary tumor has grown large enough to be detected. Red line indicates the median for individuals not diagnosed with cancer (or any of the other diseases listed) at the end of 2015. Asterisk indicates diseases that differ significantly from this group by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test after Bonferroni correcting for 144 (6*24) tests. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

The cohorts for each biomarker moderately overlap. Supplementary figure 3A shows the overlap among subjects measured for AFP, CA-15.3, CA-19.9, CA-125 and CEA. Almost all subjects also had ALP measured. Supplementary figure 3B shows the overlap among extreme outliers, defined as subjects having biomarker values >1000 for AFP, CA-15.3, CA-125 and CEA and >5000 for CA-19.9.

Results

Sequence variants associated with biomarker levels

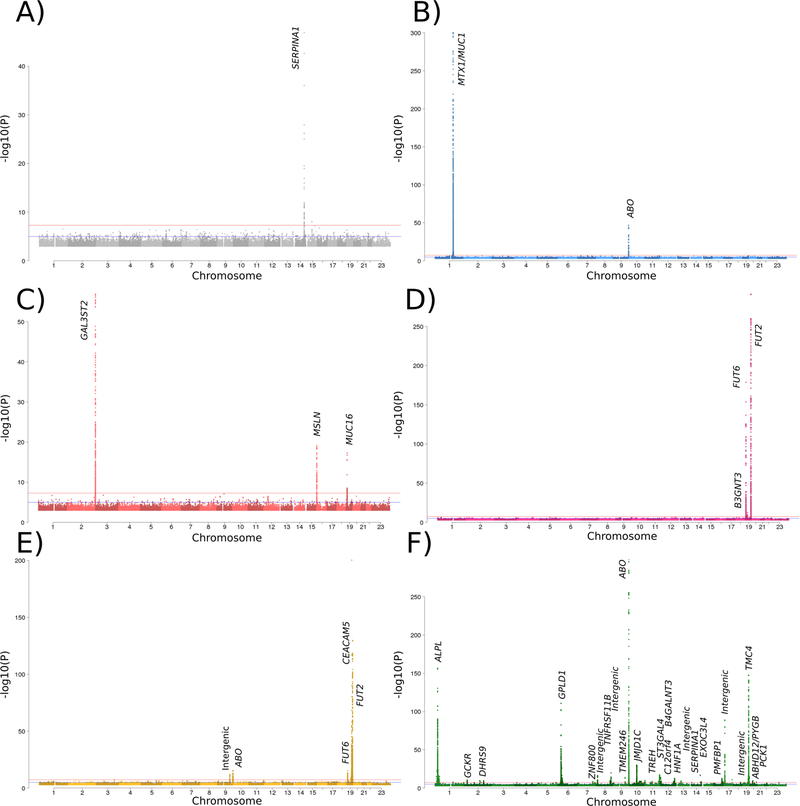

We performed a GWAS on biomarker levels with subjects ranging from 7,107 to 162,774 (Table 1) and identified 84 associations between sequence variants and biomarker levels. We found 3 sequence variants associated with AFP levels, 6 with CA-15.3, 9 with CA-125, 4 with CA-19.9, 11 with CEA and 51 with ALP (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3). To assess if any of the identified variants associates with risk of developing cancer, we tested the association between all the variants and the diagnosis of 20 cancer types in the Icelandic material. With the exception of the association of rs760077 with gastric cancer described below, none of the variants associates with the risk of developing cancer in our cohorts (P > 1 × 10−6, Supplementary figure 6). We also assessed the effect of the variants on gene expression in whole blood in a sample of 2,528 Icelanders who were whole-genome RNA sequenced (Table 3). Lastly, we performed a co-localization analysis to link the identified variants with a range of biochemical traits for which summary statistics are available at deCODE Genetics (Supplementary Table 2). We summarize the results for each biomarker below.

Figure 1:

A Manhattan plot

Figure 1 contains a Manhattan plot for A) Alpha fetoprotein; B) Cancer antigen 15.3; C) Cancer antigen 125; D) Cancer antigen 19.9; E) Carcinoembryonic antigen; F) Alkaline phosphatase.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

We found three sequence variants associated with AFP levels that collectively explain 2.3% of its variance. Two are independent missense variants in the SERPINA1 gene on chromosome 14 (rs28929474-T (Glu366Lys, allele Z) and rs17580- A (Glu288Val, allele S)) and one is a common intergenic variant at the same locus. SERPINA1 encodes the serine protease inhibitor α-1-antitrypsin and we found the minor alleles of both missense variants to be associated with decreased quantity of α-1-antitrypsin in blood in 6,452 Icelandic subjects for which this measurement was available (β = −1.71 SD, P = 1.0 × 10−83 and β = -0.61 SD, P = 2.0 × 10−38 for rs28929474-T and rs17580-A, respectively). Reduced levels of this protein are known to cause emphysema, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [17]. The same alleles that reduce SERPINA1 also associate with reduced levels of AFP. Additionally, rs28929474-T associates with higher levels of three liver enzymes [18] (Supplementary Table 2).

It is of note that we find no association of variants within the AFP gene or its promoter with serum levels of AFP. We replicate neither of the two variants reported to associate with AFP levels in the Chinese population [19] (P = 0.84 for rs12506899 and P = 0.01 with effect in the opposite direction for rs2251844).

Cancer Antigen 15.3 (CA-15.3)

We found six sequence variants associated with CA-15.3 levels that collectively explain 42.3% of its variance. Five of these variants are within 1 Mb from the MUC1 gene on chromosome 1, which encodes CA-15.3, and one lies within an intron of the ABO gene on chromosome 9. A single missense variant in MTX1, rs760077-A, explains 33.5% of the trait variance. We have previously shown that rs760077-A is associated with higher number of tandem repeats within exon 2 of MUC1, and protection against gastric cancer [20]. It is likely that the increased number of epitopes on Muc1 leads to higher apparent CA-15.3 levels in the carriers. A second variant at the locus, rs41264915-G, is associated with decreased levels of MUC1 mRNA in blood (β = −0.33 SD, P = 1.5 × 10−16), a surprising finding given that the same allele is associated with elevated CA-15.3 levels.

Cancer Antigen 125 (CA-125)

We found nine sequence variants associated with CA-125 levels that collectively explain 10.5% of its variance. One variant is within an intron of the MUC16 gene on chromosome 19, which encodes CA-125. One of the variants lies upstream of the MSLN gene on chromosome 16, which encodes mesothelin, a cell surface molecule known to bind CA-125 on the mesothelial lining [21]. We further found two low frequency missense variants rs9927389 and rs150425699 (Ala72Val and Arg557His, respectively) in MSLN, suggesting that the observed effect on CA-125 levels is mediated through structural changes in mesothelin.

Five variants are in- or close to- GAL3ST2 on chromosome 2. Of these, three are low frequency (MAF<2%) missense variants (Pro143Leu, Leu383Pro and Tyr153Cys), implicating the encoded galactose-3-O-sulfotransferase in regulation of CA-125 levels. It is presently not clear how this enzyme affects CA-125 levels. We note that the binding site of the antibody used for CA-125 detection has not been reported by the antibody’s producer and speculate that variants in GAL3ST2 may influence the glycosylation of Mucin16 and thus affect the outcome of CA-125 measurements but not necessarily the quantity of the protein in blood. Notably, these variants explain a larger fraction of the variance than does the cis-variant in MUC16 (Table 2).

Cancer Antigen 19.9 (CA-19.9)

We found four sequence variants associated with CA-19.9 levels that collectively explain 27.4% of its variance. Some are moderately correlated with variants found to associate with CA-19.9 levels in the Chinese population [19]. CA-19.9 levels are defined by antibody binding to the cell surface carbohydrate Sialyl-Lewis A and all the associated variants implicate genes known to function in the production and secretion of this molecule. We found a stop-gained variant, rs601338, in FUT2 (secretor gene of the Lewis antigen pathway), a variant upstream of FUT6, rs708686, and a variant in an intron of the FUT3 (Lewis gene), rs2608894, to associate with CA-19.9 levels. Additionally, a variant upstream of B3GNT3, rs34262244-A, which greatly affects the expression of the gene (β = −1.04, P = 1.3 × 10−296), associate with CA-19.9. B3GNT3 encodes UDP-GlcNAc-β-Gal β-1,3-N-acetlyglucosaminyltransferase 3, which plays a role in the formation of the backbone of sulfo-sialyl Lewis X tetrasaccaride structures [22].

The signals characterized by rs601338 (stop-gained in FUT2) and rs708686 (upstream of FUT6) co-localize with biochemical traits in blood (Supplementary Table 2). Among these are associations of rs708686-T with levels of Galactoside 3(4)-L-fucosyltransferase (β = −0.84 SD, P = 2.5 × 10−22), an effect consistent with reduced levels of CA19.9), and replicated associations of rs601338 with lipase levels previously reported [23].

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

Eleven sequence variants were associated with CEA levels in our study, explaining 11.9% of its variance. Again, some show moderate correlations with variants associated with CEA levels in the Chinese population [19]. Five of the variants are within 250kb from CEACAM5 gene on chromosome 9, which encodes CEA. The variants rs601338 and rs708686 in FUT2 and upstream of FUT6, respectively, that associate with CA-19.9 levels also associate with CEA but the effect of rs708686 is in the opposite direction to that on CA-19.9.

We also observed an association with an intergenic variant, rs7041150, and two independent variants upstream and downstream of ABO. One of these, rs10901252-C, associates with increased expression of ABO in whole blood (β = 1.61 SD, P = 1.8 × 10−210). The variants in ABO co-localize with several blood-related traits such as hematocrit, hemoglobin and granulocyte levels [24] and with cholesterol levels [25] (Supplementary Table 2).

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

We identified 51 variants associated with ALP levels, collectively explaining 6.9% of its variance. We confirm 13 of 14 associations reported in a recent study of ALP in European populations [26], which partially overlaps with our material. Among these are several associations with the ALPL gene on chromosome 1, driven by familial clusters carrying very rare coding variants (Table 2). The remaining variants are scattered throughout the genome, with variants in - or near genes involved in glycoprotein biology (ABO, FUT2, ST3GAL4, GPLD1, ASGR1) and carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (JMJD1C, TREH, HNF1A, B4GALNT3, PCK1, DHRS9, GCKR) being prominent. Many of these variants also co-localize with other biochemical traits, such as triglyceride concentrations [25] (Supplementary Table 2).

Out of the 51 variants, 19 are coding and 3 associate with changes in gene expression (Table 4). We found associations between rs8736-T and decreased expression of TMC4 (β = −0.97 SD, P < 10−300), between rs4654748-T and decreased expression of NBPF3 (β = −0.94 SD, P = 8.6 × 10−311) and between rs174564-G and increased expression of FADS2 in whole blood (β = 0.23 SD, P = 7.9 × 10−23).

Table 4:

Variants associated with biomarker levels and with gene expression in whole blood. EA: Effect allele; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; CA: Cancer Antigen; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen.

| rsID | Chromosome:positiona | EAb | Biomarker(s) | Gene | β [SD] | P | Covariatec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs760077 | chr1:155208991 | A | CA-15.3 | THBS3 | 0.64 | 3.4 × 10−114 | — |

| rs41264915 | chr1:155197995 | G | CA-15.3 | MUC1 | −0.33 | 1.5 × 10−16 | — |

| rs34262244 | chr19:17795098 | A | CA-19.9 | B3GNT3 | −1.04 | 1.3 × 10−296 | — |

| rs10901252 | chr9:133252613 | C | CEA | ABO | 1.61 | 1.8 × 10−210 | — |

| rs4654748 | chr1:21459575 | C | ALP | NBPF3 | −0.94 | 8.6 × 10−311 | — |

| rs174564 | chr11:61820833 | G | ALP | FADS2 | 0.23 | 7.9 × 10−23 | rs7943728 |

| rs8736 | chr19:54173495 | T | ALP | TMC4 | −0.97 | 1.0 × 10−300 | — |

The position is given for hg38.

The effect allele is the minor allele.

We condition the expression on the covariate when there is more than one variant in the region affecting the expression of the gene and the variant affecting biomarker value is not the most significant variant.

Diseases affecting biomarker levels

Given the lack of specificity of the cancer biomarkers, it is of interest to explore which conditions are likely to affect the levels of a particular marker. To search for conditions associated with elevated levels of the selected biomarkers, we compared the highest values for all individuals in a patient group with subjects without cancer diagnosis and identified several diseases where patients showed elevations in biomarker levels (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). We also compared the first measurements done on each individual (Supplementary Figure 4) as well as the proportion of the highest values falling into bins (Supplementary Figure 5) defined using the reference values used at Landspitali, the National University Hospital in Iceland (Table 1).

In general, the biomarker levels agree with the indicated clinical use of the respective biomarker but there are some interesting departures from the expected. High AFP levels are overwhelmingly found in HCC with increased levels also seen in TGCT and cirrhosis, a risk factor for HCC. The largest CA-125 levels are strongly associated with ovarian/peritoneal and pancreatic cancers as expected, but a highly significant association is also found between CA-125 levels and cancers of unknown primary site and a more moderate increase in a number of other malignancies. In addition to pancreatic cancer, CA-19.9 levels are also high in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), but the increase in other cancers is much less. CA-15.3 shows a moderate increase in several cancer types in addition to breast cancer, which does not stand out with respect to this biomarker. The levels of CEA and ALP are highest in cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, but both markers show increased levels in many cancer types and ALP levels are increased in all the non-cancer phenotypes tested as well.

Discussion

Tumor antigens are often measured in individuals with unknown ailments in search of diagnostic clues, as well as being used for monitoring the progression of tumors and response to treatment. In our study, we sought to identify variants that influence tumor biomarker values regardless of cancer diagnosis. We did not remove cancer patients from the cohort before association testing. Their inclusion adds variance to the dataset and results in more conservative estimates of the variance explained by each variant. We repeated the GWAS of the cancer antigens, excluding breast cancer, peritoneal and ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer and pancreatic, colorectal and gastric cancer patients for CA-15.3, CA-125, CA-19.9 and CEA, respectively. We observed all the same primary associations but generally larger effect estimates and higher P-values, as a result of reduced sample size. This, together with the observation that only rs760077 is associated with cancer status in the Icelandic cohorts (Supplementary Figure 6) suggests that these variants generally do not act through effect on cancer risk or aggressiveness.

We report 84 associations between sequence variants and tumor biomarker levels in the Icelandic population. While we are unaware of a study having been published on CA-15.3 and CA-125, variants affecting the other biomarkers have been reported [19, 27]. We confirmed most of those associations and discover many additional variants, some of which are rare variants with large effects. In an attempt to shed light on their biology, we tested all the variants for association with expression of genes in their vicinity and for co-localizations with biochemical traits in blood. Blood is not the most relevant tissue for any of the biomarkers and we would not be able to detect tissue or cell type specific effects. Some of the variants may also assert their influence on genes farther away than the 250 kb cut-off.

Our comparisons across cancer types show that tumor antigens are strongly associated with diagnosis of several cancers while also highlighting the lack of specificity of these tests. As demonstrated in Figure 2, many cancers other than those for which the biomarkers are most commonly used showed significant elevation of biomarker values.

A limitation and a potential source of bias in our study is that subjects were not randomly selected for biomarker assaying but rather measurements were done because of suspicion of a particular ailment, to monitor the progression of an existing disease or for some other clinical reason. In particular, the subject labeled as ‘Without cancer diagnosis’ in Figure 2 are individuals seeking medical assistance and biomarker levels may not reflect those found in healthy individuals.

The utility of genetic correction in prediction models depends on the fraction of the trait’s variance explained by sequence variants. The relatively high variance explained by identified genetic factors, for some of the cancer antigens in particular, suggests that improvements could be achieved by the inclusion of these variants in such models. A single variant, rs760077, explains >33% of the variance in CA-15.3. This biomarker is generally considered of low specificity but this high fraction of variance explained highlights the potential for improvement by correcting values for genotype. However, CA-125 is perhaps of most interest in this regard, as effective screening tools for ovarian cancer are currently lacking. Recent screening trials of ovarian cancer reported no mortality benefit from screening with CA-125 and trans-vaginal ultrasound [9, 28]. A retrospective study of these cohorts based on genotypically corrected CA-125 levels may show greater benefit of CA-125 screening. Furthermore, corrected biomarker values should be useful when combining liquid biopsies and more traditional biomarkers to detect early tumors [2].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of the staff of the genotyping and informatics facilities in deCODE Genetics and of the Icelandic Cancer registry, without whom this study would not have been possible. This study was funded by deCODE Genetics/Amgen.

Funding

This study was funded by deCODE Genetics/Amgen and supported in part by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health, under award number R01DE022905, awarded to Dr. Kari Stefansson, kstefans@decode.is.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors that are affiliated with deCODE are employees of deCODE genetics/Amgen Inc. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN. Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5(11):845–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen JD, Li L, Wang Y, et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 2018;359(6378):926–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talerman A, Haije WG, Baggerman L. Serum alphafetoprotein (AFP) in patients with germ cell tumors of the gonads and extragonadal sites: correlation between endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor and raised serum AFP. Cancer 1980;46(2):380–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas P, Toth CA, Saini KS, et al. The structure, metabolism and function of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene family. Biochim Biophys Acta 1990;1032(2–3):177–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kufe DW. Mucins in cancer: function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9(12):874–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bast RC, Jr., Hennessy B, Mills GB. The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9(6):415–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goonetilleke KS, Siriwardena AK. Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19–9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2007;33(3):266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacci G, Picci P, Ferrari S, et al. Prognostic significance of serum alkaline phosphatase measurements in patients with osteosarcoma treated with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 1993;71(4):1224–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387(10022):945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. The clinical utility of serum CA 19–9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An evidence based appraisal. J Gastrointest Oncol 2012;3(2):105–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffy MJ. Serum tumor markers in breast cancer: are they of clinical value? Clin Chem 2006;52(3):345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gudmundsson J, Besenbacher S, Sulem P, et al. Genetic correction of PSA values using sequence variants associated with PSA levels. Sci Transl Med 2010;2(62):62ra92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sigurdardottir LG, Jonasson JG, Stefansdottir S, et al. Data quality at the Icelandic Cancer Registry: comparability, validity, timeliness and completeness. Acta Oncol 2012;51(7):880–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sveinbjornsson G, Albrechtsen A, Zink F, et al. Weighting sequence variants based on their annotation increases power of whole-genome association studies. Nat Genet 2016;48(3):314–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics 2010;26(16):2069–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Brown GR, et al. NCBI Reference Sequences (RefSeq): current status, new features and genome annotation policy. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40(Database issue):D130–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. A review of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185(3):246–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prins BP, Kuchenbaecker KB, Bao Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of health-related biomarkers in the UK Household Longitudinal Study reveals novel associations. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He M, Wu C, Xu J, et al. A genome wide association study of genetic loci that influence tumour biomarkers cancer antigen 19–9, carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha fetoprotein and their associations with cancer risk. Gut 2014;63(1):143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helgason H, Rafnar T, Olafsdottir HS, et al. Loss-of-function variants in ATM confer risk of gastric cancer. Nat Genet 2015;47(8):906–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rump A, Morikawa Y, Tanaka M, et al. Binding of ovarian cancer antigen CA125/MUC16 to mesothelin mediates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem 2004;279(10):9190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh JC. FM. UDP-GlcNAc: BetaGal Beta-1,3-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase 3 (B3GNT3) In: Taniguchi N HK, Fukuda M, Narimatsu H, Yamaguchi Y, Angata T, (ed). Handbook of Glycosyltransferases and Related Genes. Tokyo: Springer; 2014, 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss FU, Schurmann C, Guenther A, et al. Fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) non-secretor status and blood group B are associated with elevated serum lipase activity in asymptomatic subjects, and an increased risk for chronic pancreatitis: a genetic association study. Gut 2015;64(4):646–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Astle WJ, Elding H, Jiang T, et al. The Allelic Landscape of Human Blood Cell Trait Variation and Links to Common Complex Disease. Cell 2016;167(5):1415–1429.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010;466(7307):707–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chambers JC, Zhang W, Sehmi J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies loci influencing concentrations of liver enzymes in plasma. Nat Genet 2011;43(11):1131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinsky PF, Yu K, Kramer BS, et al. Extended mortality results for ovarian cancer screening in the PLCO trial with median 15years follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143(2):270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.