Abstract

Large-scale structural interventions and “Big Events” like revolutions, wars and major disasters can affect HIV transmission by changing the sizes of at-risk populations, making high-risk behaviors more or less likely, or changing contexts in which risk occurs. This paper describes new measures to investigate hypothesized pathways that could connect macro-social changes to subsequent HIV transmission. We developed a “menu” of novel scales and indexes on topics including norms about sex and drug injecting under different conditions, experiencing denial of dignity, agreement with cultural themes about what actions are needed for survival or resistance, solidarity and other issues. We interviewed 298 at-risk heterosexuals and 256 men who have sex with men in New York City about these measures and possible validators for them. Most measures showed evidence of criterion validity (absolute magnitude of Pearson’s r ≥ 0.20) and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70). These measures can be (cautiously) used to understand how macro-changes affect HIV and other risk. Many can also be used to understand risk contexts and dynamics in more normal situations. Additional efforts to improve and to replicate the validation of these measures should be conducted.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Big events, Structural interventions, Risk environments, Measures development

Resumen

Las intervenciones estructurales a gran escala y los “Grandes Eventos”, como revoluciones, guerras y desastres mayores, pueden afectar la transmisión de VIH al cambiar el tamaño de las poblaciones en riesgo, hacer que las conductas de alto riesgo sean más o menos probables, o cambiar los contextos en los que se produce el riesgo. Este documento describe nuevas medidas para investigar vías hipotéticas que podrían conectar cambios macro-sociales con una posterior transmisión del VIH. Desarrollamos un “menú” de escalas e índices novedosos sobre temas que incluyen normas sobre el sexo y la inyección de drogas en diferentes condiciones, experimentar negación de la dignidad, acuerdo con temas culturales sobre qué acciones son necesarias para la supervivencia o la resistencia, la solidaridad y otros temas. Entrevistamos a 298 heterosexuales en riesgo y a 256 hombres que tienen sexo con hombres en la ciudad de Nueva York sobre estas medidas y sus posibles validadores. La mayoría de las medidas mostraron evidencia de validez de criterio (magnitud absoluta de r ≥ 0.20 de Pearson) y confiabilidad (alfa de Cronbach ≥ 0.70). Estas medidas pueden usarse (con cautela) para comprender cómo los cambios macroeconómicos afectan el VIH y otros riesgos. Muchas de estas medidas también pueden usarse para comprender contextos de riesgo y dinámicas en situaciones más normales. Se deben realizar esfuerzos adicionales para mejorar y replicar la validación de estas medidas.

Introduction

This article presents data on the reliability and validity of a number of new measures for studying changes in HIV vulnerability for MSM and for at-risk heterosexuals.1 These measures are based on theories of how large-scale negative or positive structural interventions or Big Events might lead to short-term and long-term changes in HIV epidemics and/or in the size and riskiness of populations of people who use drugs, engage in sex work, or otherwise engage in high-risk sexual networks. Nonetheless, they are also applicable to other research and surveillance issues, including research into how stable social structures such as institutional racism might create dignity denial and stigma as pathways that in turn are associated with high HIV risk.

Causal pathways between large-scale events and individual responses are important—but hard to study. For HIV prevention and care, we need to know more about how socioeconomic changes such as wars, transitions or revolutions, economic crises, major social (structural) interventions, and ecological events like hurricanes or global warming, can affect risk networks, risk behaviors and behaviors relevant to care.

Our previous work has suggested that such changes sometimes seem to unleash HIV outbreaks but also that some such Big Events are not followed by outbreaks [1]. We proposed a theoretical approach concerning processes that lead to these disparate outcomes based on Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) [2]. A main point made by that paper is that the effects of Big Events or large-impact structural interventions on HIV risk behaviors, networks and transmission are not direct ones, but depend on how, in a given instance, they affect a number of normative and social-structural pathways. The paper also proposed ways to categorize such pathways based on CHAT. Another paper described how we developed such measures for people who inject drugs (PWID) and presented evidence for the reliability and validity of these measures for PWID [3]. Nikolopoulos et al. presented data on the relationship of some of these measures to the HIV outbreak that started in 2011 among PWID in Athens [4]. They concluded that the effects of Big Events likely come in stages:

First, they may affect the risk behaviors and networks of PWID or members of other Key Populations;

Then, if an outbreak occurs among a Key Population, they may affect the behaviors and networks that link this Key Population to other sex partners; and

Over the long run (of approximately 5 to 10 years), they may lead people who were adolescents at the time the Big Event or structural intervention occurred to engage in high-risk drug use or sexual behaviors in high-risk networks or venues.

In this paper, we describe similar measures we developed for two additional Key Populations: Men who have sex with men (MSM) and at-risk heterosexuals (ARH). We also present data on the reliability of scales in these populations and on the criterion validity of these measures.

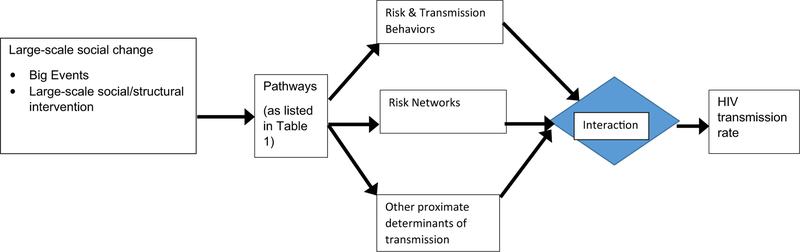

Before describing the Methods, it will be valuable to present the theoretical perspectives underlying these measures. Figure 1 presents a very brief schematic of the overall hypothesized context in which large-scale social changes are mediated by “pathways” to affect the proximate causes of HIV transmission and thus to affect the probability that an HIV epidemic will break out. Table 1 presents a categorization of pathways and of categories of constructs that fall within each. Unlike the categorization that we used in our paper on the reliability and validity of these measures for studying PWID, [3] which were derived from Cultural-Historical-Activity Theory (CHAT), the categorization in Table 1 is interpretable under a variety of theoretical approaches and disciplines that might find these measures useful.

Fig. 1.

Basic process model showing pathways as mediators

Table 1.

Categories and examples of pathways

Active norms and rules about behaviors in

proximal social contexts

|

Dependency on others

|

Formal and informal group involvement

|

Dignity denial

|

Social conflicts and reactions to them

|

Personal or cultural orientations about how

to respond to difference, threats and opportunities

|

Attitudes toward and perceptions of

others’ attitudes toward male socio-sexual dominance and gay

people

|

Thus, the overarching goal of this project was to create measures that did not already exist that would help explain why Big Events or structural interventions might lead to different outcomes under different situations. Our main focus was on measures that would help researchers understand how the immediate social environments of people who might be potentially at risk were changing, how the activities and organizational commitments of participants and their neighbors were changing, and how participants’ tendencies to respond to changes in their environments or activities might be changing. To the extent possible, we thus focused on asking respondents to report on what they experienced or what they observed going on around them, although in asking about their “orientations” to how to respond and in some other questions we to a degree asked them about their beliefs, perceptions or attitudes. Categories of these measures include the following:

Reports on actual experiences and on the social relationships they encountered include:

Many measures take the form of “active norms” in which respondents are asked to report on the extent to which others actively encourage them to engage in or refrain from some behavior or relationship. These are sometimes phrased as occasions in which others “actually objected” to something like sharing syringes. We developed this form of asking about active norms in earlier studies, [5–7] but are here applying this form to new substantive areas that tie into how Big Events or structural interventions might unleash epidemics.

Whether group sex or drug using venues which they attended had rules about safer behavior and/or roles like bouncers to protect participants.

Witnessing verbal or physical assaults on others.

Undergoing attacks on your dignity by others; or witnessing people attack the dignities of other people. We discussed dignity attacks as social processes, our findings in this study about them, and how they might be related to risk behaviors and other proximate causes of epidemics, in earlier papers. [8, 9]

The extent to which they depend on relatives, friends, and/or service agencies for various needs.

In the MSM questionnaire, a scale on how many people in their community accept or do not accept specific stigmas against gay people.

Reports on respondents’ activities and organizational commitments included:

What they did when their own or someone else’s dignity was attacked. These include explicit measures of whether they increased risk behaviors.

Their formal and informal organizational involvements. These variables have been analyzed substantively for PWID. [10] In general, organizational resources and commitments, and friendships made in organizational contexts, can affect risk behaviors, risk networks, and probabilities of seeking care for substance use problems or STIs.

Altruistic actions they engage in. These have been studied separately for PWID. [11]

Reports on how participants tendencies to respond to changes in their environments or activities included a series of what we call “orientation” scales. Most items in these scales are attitudinal ones about how people should respond to various situations or structural realities. These include scales that measure whether respondents tend to respond to situations:

Altruistically,

with solidarity, and/or

competitively.

Finally, after we had collected data on PWID, we developed two new attitudinal scales about participants’ own perceptions on male socio-sexual dominance and on what they believe to be the attitudes of their friends and family.

Methods

Samples

The sample consists of 298 ARH (284 of whom did not inject drugs in the last 30 days), and 256 MSM (240 of whom did not inject drugs in the last 30 days). Many of the ARH and MSM were referred to our study by a large New York City respondent driven sample (RDS) study in 2012–2015. The ARH were interviewed from Sept. 2013 through May 2014; the MSM from November 2014 through August 2015. For ARH and MSM we supplemented the sample referred to us by the other study by asking participants to help us recruit others who would qualify. The project field director screened potential participants for eligibility (usually over the telephone). Eligibility criteria included [1] age 18 or older, [2] NYC metropolitan area residence, and [3] English fluency. ARH also had to report having had sex in the previous 12 months with an opposite-sex partner; and MSM had to be male and report having had sex in the last 12 months with another man. (MSM and ARH could also have had sex with women).

Measures

Qualitative Research to Develop the New Measures

To help develop new and grounded pathways measures, we conducted formative qualitative research using in-depth interviews and focus groups with PWID, MSM and ARH in 2012–2014. We conducted four focus groups, 18 in-depth interviews, and 17 pilot interviews to help us understand each conceptual area of interest. Qualitative analysis included holding periodic project meetings at which we discussed the content of the interviews and transcripts and brainstormed about additional issues to explore in in-depth interviews or focus groups. This let us develop lists of more specific constructs for which to develop questionnaire items or scales. We then drafted initial lists of candidate question topics. In wording these questions and response categories, we drew on language participants had used in focus groups and in-depth interviews. We elicited feedback from selected participants (chosen as knowledgeable and willing to assist us—essentially, they were “informants for this part of the study) and from our scientific advisory board members to help in revising the questions. Our pathways measures are new, but some of them extend or complement existing measures, e.g., of stigma and norms about condom use and partner selection [7, 12–19].

Interviews to Test the Reliability and Validity of These Measures

Participants were interviewed with informed consent. The questionnaire covered activities, experiences, norms and roles in specific contexts, and how normative conflicts and other situations were perceived and resolved [3, 16]. Study methods and questionnaire items were approved by National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI)’s Institutional Review Board. Interviews typically took between 90 and 120 min. Participants generally reported that they enjoyed the interview topics and felt respected. They were reimbursed $30 for their time and effort.

In addition to standard demographic and behavioral items, respondents were asked about a number of questions as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | At-risk heterosexuals %a,b (n)/Mean (standard deviation) | Men who have sex with men %a,b (n)/Mean (standard deviation) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 30.1 (88) | 39.7 (100) |

| 25–29 | 27.7 (81) | 41.7 (105) |

| 30–39 | 14.8 (44) | 17.5 (44) |

| 40–49 | 14.8 (44) | 1.2 (3) |

| 50–68 | 11.7 (35) | |

| Gender (% male) | 51.0 (152) | 100% (256) |

| Racial category | ||

| White | 20.1 (60) | 34.8 (89) |

| Black/African American | 71.8 (214) | 61.7 (158) |

| Otherc | 6.8 (20) | 3.1 (8) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 32.6 (97) | 42.2 (108) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 73.8 (220) | 65.2 (167) |

| Married or living together | 14.1 (42) | 32.0 (82) |

| Same-sex married | 64.8 (57) | |

| Opposite-sex married | 34.1 (30) | |

| Divorced, separated or widowed | 12.1 (36) | 2.8 (7) |

| Educational achievement | ||

| Less than high school graduation | 35.9 (107) | 26.6 (68) |

| High school graduate or GED | 45.0 (134) | 43.4 (111) |

| More than high school graduate | 19.2 (57) | 30.1 (77) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed full-time or part-time | 24.5 (73) | 46.9 (56) |

| Student | 3.7 (11) | 6.3 (16) |

| Unable to work due to disability or retired | 7.7 (23) | 4.7 (12) |

| Homemaker | 3.7 (11) | 1.6 (4) |

| Unemployed | 59.7 (178) | 39.1 (100) |

| Other, including illegal activities | 0.7 (2) | 1.6 (4) |

| Income category (per year) | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 45.3 (135) | 27.3 (70) |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 49.3 (147) | 53.9 (138) |

| $20,000 or more | 5.4 (16) | 18.8 (48) |

| Number of dependents (Mean (SD)) | 1.9 (1.04) | 1.8 (0.90) |

| Veteran of U.S. armed forces or reserves | 12.4 (37) | 16.0 (41) |

| Homeless status | 11.1 (33) | 18.4 (47) |

| HIV infection status (% positive) | 5.7 (17) | 11.3 (23) |

| Sexual behavior | ||

| Number of opposite-sex partners (last year) [Mean (SD)] | 2.0 (2.91) | – |

| Any same-sex partners last year | 24.8 (74) | – |

| Number of sex partners (last year) [Mean (SD)] | – | 2.1 (1.33) |

| Had unprotected sex with a non-main partner (last 30 days) | – | 17.2 (44) |

| Exchanged sex for money, drugs or other goods (last 30 days) | 11.7 (30) | 27.7 (71) |

| Attended multi-partnered sex events (last year) | 19.5 (58) | 20.9 (53) |

| Used condoms consistently during multi-partnered sex events (last year) | 4.0 (12) | 48.9 (23) |

| Drug use behavior | ||

| Ever injected drugs | 23.2% (69) | 17.7% (45) |

| Injected drugs (last 30 days) | 4.7 (14) | 4.3 (11) |

| Smoked crack (last 30 days) | 18.8 (56) | 5.5 (14) |

| Weekly binge drinking [(5 + alcoholic drinks) last 30 days] | 65.8 (196) | 84.3 (215) |

| Used erection medication (last 30 days) | – | 32.7 (81) |

N = 298 at-risk heterosexuals and 256 men who have sex with men

1Percentage and (n), unless otherwise noted mean and (standard deviation)

Sample sizes (n) for category percentages vary due to non-response for some items, and percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding

Other = American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific islander, and multiple racial groups

Analysis

Analytic methods were described in some depth in our paper on pathways measures among people who inject drugs so we will present only an abbreviated discussion here [3]. On terminology, we use “index” to refer to the sum of responses to interview questions that are theoretically interrelated and that are themselves dichotomies. “Scales” is used for theoretically-linked items for which the responses are in ordinal Likert-type categories such as “never” to “all of the time.”

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency. We designed scales to measure only one unidimensional construct. We removed items with the lowest item-total correlations below 0.20 one at a time until there were no longer any below 0.20 since they are unlikely to be related to the construct. Values of Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 are usually considered reliable for most research purposes, though higher values are better [20]. To avoid omitting cases due to a missing value on one item, we report scales as an unweighted average of the items that compose them. Items were reverse coded so items in a given scale would have the same direction in relation to the underlying construct. The various pathways measures are described more completely in Online Appendices A and B.

Validlity

Validity refers to the extent to which a measure actually measures its underlying construct. This is usually done by assessing the measure’s associations with specified criterion variables. Our measures were constructed precisely because there were no other measures for what they were meant to measure, so it was difficult to find criterion variables. In general, we chose validators that have some face validity as measures that should be correlated with a given measure regardless of the relationship of the validator to HIV. Thus, it would be unreasonable to expect high associations with the criterion variables we have, so in general we accept a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of magnitude 0.2 in the desired direction as reasonable validation and anything above r = 0.3 as fairly strong validation. (For N > 100, r = 0.2 is significant at the 0.05 level for a two-tailed test.)

Given this uncertainty about what would be the best validator, in some cases we assessed associations with several potential validators. These are included in Table 4 or its footnotes.

Table 4.

Summary list of measures together with the degree to which we judge them to have been shown to be reliable and valid for the at-risk heterosexual and MSM populations reported on here

| At-risk heterosexuals | Men who have sex with men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability (α) | Validity | Reliability (α) | Validity | |

| Active norms and rules about behaviors in proximal social contexts | ||||

| • Active Norms on increasing sexual risk behavior | + | +! | (See below) | |

| • Active norms on increasing sexual risk behavior | ++ | This pattern is what we would expect | ||

| ◦ Of close relatives; | + | |||

| ◦ Of gay friends (for MSM); | + | |||

| ◦ Of non-gay friends (for MSM)) | No | |||

| ++ | ||||

| No | ||||

| • Active Norms on injectable drug behaviors | + | ++ | ?? | +! |

| • Rules at multi-partnered sex events | + | No | + | ++ |

| • Enforcement of norms at group sex events | .66 | Mixed evidence | + | No |

| • Sex rules at drug-using venues | ++ | + | ++ | No |

| Dependency on others | ||||

| • Dependency on relatives | + | +! | + | +!? |

| • Dependency on friends | ? | +! | + | +! |

| • Dependency on service agencies | + | +! | + | ++ |

| • Dependency on sex partners | ++ | ?? | ++ | +! |

| Formal and informal group involvement | ||||

| • Involvement with formal groups | INDEX | + | INDEX | No |

| • Involvement with informal groups | INDEX | No | INDEX | ? |

| • Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities | +! | + | ?! | |

| Dignity denial | ||||

| • Dignity denial perpetrators | INDEX | +! | INDEX | +! |

| • Dignity denial characteristic targeting | INDEX | ?? | INDEX | +1 |

| • Reactions to dignity denial | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| • Witnessing dignity denial perpetrators | INDEX | +! | INDEX | ? |

| • Reactions to witnessing dignity denial | + | ?? | .68 | No |

| Social conflicts and reactions to them | ||||

| • Witnessing verbal and physical attacks on others | ++ | No | ++ | ++ |

| • Witnessing defense of and assistance to others | + | + | .69 | ? |

| • Intergenerational normative disjuncture (by age category) | + | No | ++ | ++ |

| • Younger adults | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| • Older adults | + | ? −0.13 | ++ | ++ |

| Personal or cultural orientations about how to respond to difference, threats and opportunities | ||||

| • Altruistic cultural orientation | ++ | ++ ! | + | ++ ! |

| • Altruistic actions: Frequency of helping others | ++ | ++ ! | + | ++ ! |

| • Solidarity cultural orientation | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| • Struggle cultural orientation | + | + | + | + |

| • Traditional cultural orientation | ++ | ++ ! | + | ? |

| • Competitiveness cultural orientation | + | No | ++ | + |

| • Hostility cultural orientation | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| • Survival cultural orientation | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Attitudes toward and perceptions of others’ attitudes toward male socio-sexual dominance and gays | ||||

| • Masculine socio-sexual dominance orientation (self) (ARH only) | ++ | + | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| • Perception of extent to which friends and family have masculine socio-sexual dominance orientation (ARH only) | ++ | + | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| • Perception of Community Involvement or Opposition to Gay Stigma (MSM only) | Not applicable | Not applicable | ++ | + |

On reliability, ≥ 0.70 is indicated by +; but ≥ .80 is indicated by ++. ? indicates less than 0.70 but ≥ 0.60

On validity, + is used for correlations of ≥ 0.20; and ++ for ≥ 0.30. The ! sign indicates a situation of multiple validators that reduces our confidence in the validation

Results

Table 2 shows participants characteristics for both ARH and MSM. Since this paper is focused on the reliability and validity of measures within each population, we do not discuss differences between these populations except in passing. For both groups, the majority of participants were less than 30 years of age. Half of the ARH were of each sex. Perhaps because of the location of the project that referred participants to us, most participants were Black/African American and a large proportion of each sample was Hispanic. 74% of ARH and 65% of MSM had never been married, and only 14% of ARH and 32% of MSM were living with partners. Pluralities of each group were high school graduates or had GEDs. About a quarter of ARH and almost half of MSM had some employment, although this was often part-time work, and 60% of ARH and 39% of MSM reported being unemployed. Incomes were quite low, which probably at least partially reflects the high proportion who were Black/African American or Hispanic racial/ethnic as well as who was willing to take part in the survey: only 5% of ARH and 27% of MSM reported incomes of $20,000 or more. Eleven percent of ARH and 18% of MSM reported being currently homeless.

Self-reported HIV rates were 6% for ARH and 11% for MSM, which can be compared with National HIB Behavioral Study findings for ARH of 3.9% in 2013 and for MSM of 14.8% in 2014 [21]. Exchange sex was reported by 12% of ARH and 28% of MSM in the last 30 days. Twenty percent of each group attended a group sex event in the last year. Both of these suggest a potential high rate of connection among otherwise-separate sexual networks [22, 23]. The mean numbers of partners for each group was two or above.

Drug injection was present but rare (less than 5%) for each group. Other drug use, including erectile dysfunction medicines by MSM, and binge drinking were common.

Reliabilty

Table 3 presents the measures for at-risk heterosexuals and for MSM within the categories presented in Table 1, their numbers of items, Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability values, and Pearson correlations with their criterion variables (validators). Scale reliabilities for those measures which were multi-item scales were 0.70 or above for most items; in every case but one, the reliability of the others was 0.60 or above.

Table 3.

Pathways index and scale characteristics and correlations with criterion variables or vignette items

| CHAT label | Pathways measure | n | Number of items/categories | Mean (standard deviation) | Range | Cronbach’s alpha | Criterion variable(s) | Correlation with criterion variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. At-risk heterosexuals | ||||||||||

| Active norms and rules about behaviors in proximal social contexts | ||||||||||

| A2 | Active Norms on increasing sexual risk behavior | 292 | 6 | 1.4(0.65) | 1–10 | 0.74 |

|

|

||

| A3 | Active Norms on injectable drug behaviors | 292 | 6 | 1.4(0.46) | 1–3.7 | 0.70 |

|

|

||

| A4 | Rules at multi-partnered sex events | 51 | 9 | 2.2(0.55) | 1–6 | 0.73 | Attended any group sex event in last year | 0.05 | ||

| A5 | Enforcement of sex norms at group sex events | 59 | 3 | 3.2(0.98) | 1–5 | 0.66 | Number of group sex events they attended in last year one | −0.23 | ||

| A6 | Sex rules at drug-using venues | 214 | 13 | 2.1(0.73) | 1–4.4 | 0.83 | Attended a multi-partner sex event | 0.26 | ||

| Dependency on others | ||||||||||

| A9 | Dependency on relatives | 298 | 8 | 3.1(1.05) | 1–9.4 | 0.78 |

|

|

||

| A10 | Dependency on friends | 298 | 8 | 2.0(0.49) | 1–4.5 | 0.60 |

|

|

||

| A11 | Dependency on service agencies | 298 | 6 | 2.2(0.89) | 1–5 | 0.71 |

|

|

||

| A12 | Dependency on sex partners | 212 | 9 | 2.4(1.00) | 1–5 | 0.88 |

|

|

||

| Formal and informal group involvement | ||||||||||

| B1 | Involvement with formal groups (index) | 298 | 33 | 0.8(0.80) | 0–4 | Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities (A1 below) | 0.26 | |||

| B2 | Involvement with informal groups (index) | 298 | 13 | 0.2(0.54) | 0–5 | Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities (A1 below) | 0.07 | |||

| A1 | Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities | 251 | 6 | 2.6(0.60) | 2–6 | 0.88 | Involvement with:

|

|

||

| Dignity denial | ||||||||||

| C1 | Dignity denial perpetrators (index) | 240 | 39 | 4.0 (2.44) | 1–12 |

|

|

|||

| C2 | Dignity denial characteristic targeting (index) | 235 | 25 | 4.8(2.40) | 1–13 |

|

|

|||

| C3 | Reactions to dignity denial | 239 | 9 | 2.9(0.57) | 1.9–5.6 | 0.81 |

|

|

||

| C4 | Witnessing dignity denial perpetrators (Index) | 284 | 39 | 3.1(0.68) | 1–12 |

|

|

|||

| C5 | Reactions to witnessing dignity denial | 284 | 4 | 1.3(0.73) | 1–13 | 0.70 |

|

|

||

| Social conflicts and reactions to them | ||||||||||

| C6 | Witnessing verbal and physical attacks on others | 298 | 17 | 2.1(0.48) | 1.9–5.5 | 0.83 | In the last year, how often have people spoken or acted towards you in a way that felt like they were attacking your dignity or demeaning you? | 0.09 | ||

| C7 | Witnessing defense of and assistance to others | 298 | 9 | 1.8(0.40) | 1–3.6 | 0.71 | In the last year, how often have people spoken or acted towards you in a way that felt like they were attacking your dignity or demeaning you? | 0.21 | ||

| C8 | Intergenerational normative disjuncture (younger adults) | 104 | 11 | 2.3(0.36) | 1.2–3 | 0.75 | # of recent sex partners | 0.45 | ||

| C9 | Intergenerational normative disjuncture (older adults) | 194 | 9 | 2.2(0.42) | 1.1–3 | 0.78 | # of recent sex partners | −0.13 | ||

| Personal or cultural orientations about how to respond to difference, threats and opportunities | ||||||||||

| C10 | Altruistic cultural orientation | 298 | 13 | 3.7(0.76) | 2–5 | 0.86 |

|

|

||

| B3 | Altruistic actions: Frequency of helping others | 298 | 11 | 3.4(0.51) | 1.9–5.6 | 0.83 |

|

|

||

| C11 | Solidarity cultural orientation | 298 | 8 | 3.2(0.76) | 1.6–6.9 | 0.70 | Competitiveness | 0.51 | ||

| C12 | Struggle cultural orientation | 298 | 7 | 3.8(0.76) | 1.5–5 | 0.73 | Traditional cultural orientation | −0.24 | ||

| C13 | Traditional cultural orientation | 298 | 17 | 2.8(0.67) | 1–4.8 | 0.84 |

|

|

||

| C14 | Competitiveness cultural orientation | 298 | 11 | 3.5(0.70) | 1.2–5 | 0.79 | Sex trading | 0.06 | ||

| C15 | Hostility cultural orientation | 298 | 10 | 2.4(0.74) | 1–4.7 | 0.80 | Solidarity cultural orientation | −0.20 | ||

| C16 | Survival cultural orientation | 298 | 11 | 3.2(0.85) | 1–5 | 0.86 | Traditional cultural orientation | −0.57 | ||

| Attitudes toward and perceptions of others’ attitudes toward male socio-sexual dominance and gays | ||||||||||

| C17 | Masculine socio-sexual dominance orientation (self) | 212 | 9 | 2.2(0.84) | 1–4.6 | 0.87 | Traditional cultural orientation | −0.28 | ||

| C18 | Perception of extent to which friends and family have masculine socio-sexual dominance orientation | 212 | 14 | 2.4 (0.69) | 1–4.1 | 0.85 | Traditional cultural orientation | −0.29 | ||

| CHAT label* | Pathways measure | n | Number of items/categories | Mean (standard deviation) | Range | Cronbach’s alpha | Criterion variables | Correlation with criterion variables | ||

| b. Men who have sex with men | ||||||||||

| Active norms and rules about behaviors in proximal social contexts | ||||||||||

| A2a | Active norms on increasing sexual risk behavior–close relatives | 255 | 7 | 2.9(0.8) | 1–4.9 | 0.83 | Number of sex partners in last 30 days | −0.01 | ||

| A2b | Active norms on increasing sexual risk behavior—gay friends | 253 | 7 | 2.8(0.8) | 1–5 | 0.78 | Number of sex partners in last 30 days | −0.52 | ||

| A2c | Active norms on increasing sexual risk behavior—nongay friends | 250 | 6 | 2.6(0.8) | 1–5 | 0.73 | Number of sex partners in last 30 days | 0.07 | ||

| A3 | Active Norms on injectable drug behaviors | 245 | 3 | 1.5(0.5) | 1–3.3 | 0.58 |

|

|

||

| A4 | Rules at multi-partnered sex events | 26 | 8 | 2.2(0.7) | 0.8–4.1 | 0.77 | How many group sex events they attended in last year | K12=037 | ||

| A5 | Enforcement of norms at group sex events (Note that the questions used to construct this variable differs from those for the heterosexual sample) | 45 | 4 | 3.3(0.9) | 1–5 | 0.77 | How many group sex events they attended in last year | 0.02 | ||

| A6 | Sex rules at drug-using venues | 129 | 11 | 2.7(0.9) | 1–5 | 0.84 | How many group sex events they attended in last year | −0.11 | ||

| Dependency on others | ||||||||||

| A9 | Dependency on relatives | 254 | 8 | 3.0 (0.7) | 1–4.6 | 0.76 |

|

|

– | 0.07 |

| A10 | Dependency on friends | 255 | 8 | 2.1(0.5) | 1–3.5 | 0.78 |

|

|

||

| A11 | Dependency on service agencies |

256 | 8 | 1.8(0.6) | 1–3.5 | 0.77 |

|

|

||

| A12 | Dependency on sex partners |

253 | 8 | 3.1(0.9) | 1.4–4.9 | 0.82 |

|

|

0.26 | −0.13 |

| Formal and informal group involvement | ||||||||||

| B1 | Involvement with formal groups (index) | 256 | 33 | 0.9(0.8) | 0–3 | Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities | −0.04 | |||

| B2 | Involvement with informal groups (index) | 256 | 13 | 0.4(0.6) | 0–3 | Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities | 0.19 | |||

| A1 | Active Norms on participating in organizations or in groups’ activities | 163 | 6 | 2.6(0.4) | 2–4 | 0.79 |

|

|

||

| Dignity denial | ||||||||||

| C1 | Dignity denial perpetrators (Index) | 256 | 39 | 3.9(2.2) | 0–11 | – |

|

|

||

| C2 | Dignity denial characteristic targeting (Index) | 256 | 25 | 4.6(2.4) | 0–12 |

|

|

|||

| C3 | Reactions to dignity denial | 194 | 9 | 3.1(0.6) | 2–4.8 | 0.74 |

|

|

||

| C4 | Witnessing dignity denial

perpetrators (Index) |

256 | 39 | 5.7(2.1) | 1–13 | – |

|

|

||

| C5 | Reactions to witnessing dignity denial | 218 | 4 | 3.1(0.6) | 1–4.8 | 0.68 |

|

|

||

| Social conflicts and reactions to them | ||||||||||

| C6 | Witnessing verbal and physical attacks on others | 247 | 14 | 2.1(0.5) | 1–4 | 0.83 | Dignity denial perpetrators (Index) | 0.31 | ||

| C7 | Witnessing defense of and assistance to others | 255 | 8 | 2.0(0.5) | 1–2.6 | 0.69 | Dignity denial perpetrators (Index) | 0.15 | ||

| C8 | Intergenerational normative disjuncture (younger adults) | 102 | 9 | 2.3(0.4) | 1.3–3 | 0.77 | Dignity denial perpetrators (Index) | 0.39 | ||

| C9 | Intergenerational normative disjuncture (older adults) | 152 | 6 | 2.2(0.5) | 1–3 | 0.84 | Dignity denial perpetrators (Index) | −0.41 | ||

| Personal or cultural orientations about how to respond to difference, threats and opportunities | ||||||||||

| C10 | Altruistic cultural orientation | 242 | 10 | 3.5(0.8) | 1.7–7.2 | 0.77 |

|

|

||

| B3 | Altruistic actions: Frequency of helping others | 49 | 8 | 3.3(0.5) | 2.1–5 | 0.78 |

|

|

||

| C11 | Solidarity cultural orientation | 251 | 9 | 2.9(0.8) | 1.4–4.9 | 0.80 | Hostility cultural orientation | 0.49 | ||

| C12 | Struggle cultural orientation | 252 | 10 | 3.9(0.6) | 2.6–5 | 0.76 | Hostility cultural orientation | 0.25 | ||

| C13 | Traditional cultural orientation | 246 | 9 | 2.2(0.7) | 1–4.3 | 0.71 | Hostility cultural orientation | 0.14 | ||

| C14 | Competitiveness cultural orientation | 255 | 14 | 2.5(0.8) | 0.8–4.1 | 0.86 | Hostility cultural orientation | 0.22 | ||

| C15 | Hostility cultural orientation | 238 | 8 | 2.2(0.8) | 0.3–4.1 | 0.80 | Solidarity cultural orientation | −0.20 | ||

| C16 | Survival cultural orientation | 253 | 12 | 2.7(0.9) | 0.5–5 | 0.89 | Hostility cultural orientation | 0.47 | ||

| Attitudes toward and perceptions of others’ attitudes toward male socio-sexual dominance and gays | ||||||||||

| C17 | Perception of community involvement or opposition to gay stigma | 253 | 6 | 0.3(0.7) | 1.2–2 | 0.89 | For gay and bisexual people things will only get better if we organize politically | 0.22 | ||

This column is presented to facilitate comparisons with our paper about the reliability and validity of these scales for people who inject drugs, since as indicated in the text, that paper used cultural-historical activity theory as a framework for presentation of its results [3]

Bolded correlation values are significant at the two-tailed 0.05 level

Validity

Table 3 also presents the correlations of measures with the items we chose to use as validators for them based on the theoretical likelihood that those high on the measures would be high (or low) on the validator. The pattern of results here is mixed, which may reflect difficulties in finding good validators for some items. In discussing these results, we present the main findings within major categories of the measures; within these, we first present findings for at-risk heterosexuals, and then for men who have sex with men.

For measures of active norms and rules in proximal social contexts, for heterosexuals there is at least one validator for which the absolute value of r is ≥ 0.20 for each pathway measure. For “enforcement of sex norms at group sex events” the sign is negative (r = − 0.23). This may reflect risk-averse people both going to fewer group sex events and also, when they do go, choosing to go to ones where safety rules are enforced, and risk tolerant people going to more group sex events and also trying to avoid those with strict rules. Among MSM, active norms on injection behaviors was strongly validated by its r = 0.55 with being a PWID, and the existence of rules at group sex events they attended was validated by its r = 0.37 with the number of group sex events they attended. The correlation of 0.52 between gay friends’ active norms on increasing sex behaviors and number of sex partners in the last 30 days is probably validation if we assume that gay men in New York are less likely to urge those friends who have sex with a lot of other people to have even more partners. The lack of correlation between the number of sex partners and active norms on sexual risk behavior as expressed by close relatives and by non-gay friends (as opposed to the active norms of gay friends) provides discriminant validation for these norms questions.

That the measures of dependency on others are associated with a number of potential validators make sense although the large number of comparisons weakens our confidence in their validity. Having been diagnosed with HIV is associated with more dependence on relatives among heterosexuals and on service agencies among MSM (who have community-rooted service agencies and also may have strained ties with some relatives). Higher income is associated with less dependency on relatives and service agencies among MSM. Being employed (as opposed to not having a job) is associated with less dependence on service agencies among both heterosexuals and MSM and less dependence on friends among MSM. Homelessness is associated with more dependency on friends among heterosexuals.

Having friends urge you to participate in organizations and groups is correlated with being active in such groups for heterosexuals. For MSM, the highest relevant correlation is only 0.19. Correlations of this active norms scale with involvement with informal groups was essentially zero for both heterosexuals and MSM, but this probably reflects the fact that most items in the norm scale referred to urging involvement with formal groups.

An earlier paper described frequencies of responses to the dignity denial questions and some of the variables they were associated with for a subset of the sample studied here [8]. For this paper, our focus is on the validity of these measures. We used their associations with witnessing attacks on, and assistance to, others as our validator on the assumption that localities and social contexts where people’s dignity was attacked would also be paces where other forms of attack would take place and where people would offer assistance to others. For both heterosexuals and MSM, three out of five of our dignity attack measures had at least one association > 0.20 with at least one validator. Our scale measuring the intensity of reactions to dignity denial had very high (≥ 0.40) correlations with each of two validators for heterosexuals.

As measures of social conflicts and reactions to them, we used the frequency with which others attacked participants’ dignity as a validator for scales on seeing verbal and physical attacks on others and on seeing defense of and assistance to others. For heterosexuals, the correlation for the first of these measures was small, but the second measure was validated (r = 0.21). For MSM, the first measure was fairly strongly validated (r = 0.31) but the second measure was not.

We also developed a second set of social conflict variables to measure intergenerational normative disjuncture— the extent to which younger adults (aged 18–24) saw differences between their generation and older generations (25 and above), and vice versa. Underlying this set of measures is the idea that major social changes or interventions can cause “generation gaps” in expectations, experiences and values [1, 3]. For heterosexuals, we used number of recent sex partners as a validator, on the basis that having many sex partners would cause different reactions for older and younger generations. Among younger adults, this was strongly validated (r = 0.45), suggesting that youth who engage in sex with many partners are normatively estranged from older adults. For older adults, this measure was not validated in this way. For MSM, both measures were strongly validated in terms of their associations with how many kinds of dignity attacks they underwent (with the signs on these associations being in opposite directions, as expected, with older adults having their normative distance from youth associated with encountering fewer dignity denial attacks).

We developed a number of personal/cultural orientation measures about how people respond to differences, threats and opportunities and validated them against each other. Almost all of them validated for heterosexuals and also for MSM (some with correlations less than or equal to − 0.20 when they have opposite polarity). The fact that solidarity and competitiveness are highly correlated could be expected since the competitiveness measure includes items about group competitiveness, which includes in-group solidarity as a prerequisite.

For the heterosexual and MSM interviews, we developed a series of measures about participants attitudes toward male socio-sexual dominance and towards gay people, including measures about how their friends and family views these issues. For heterosexuals, these measures successfully validated against traditional cultural orientation, since the traditional cultural norms scale reflects sexually conservative values, while the male dominance scale reflects sexually unrestrained values. In other words, endorsing male sexual dominance and entitlement is negatively correlated with endorsing traditional prudish attitudes about sex, class and drug use. For MSM, this took the form of a scale on perception of community involvement in or opposition to stigma against gay people, and it validated against a question about the extent to which participants thought that the conditions of gay and bisexual men would only get better if they organized politically.

Discussion

This paper is unusual: It presents a number of new measures and findings on their reliability and validity for two separate key HIV-affected populations—at-risk heterosexuals and men who have sex with men. It is a companion paper for earlier work in which we presented reliabilities and validity information for similar variables among people who inject drugs. [3]

These measures are a menu of possible measures for other researchers to use, depending on their research focus and population of interest. Since we designed these measures in response to a need for variables with which to study the effects of Big Events or of macro-social interventions, we anticipate that they will be used mainly in such studies. One clear example of this would be a study of the HIV-relevant effects of the combination of the wresting of budgetary authority from the government of Puerto Rico by the US Federal government (and its privatizations and structural adjustments) followed by devastating hurricanes in 2017.

Many of these measures will also be useful in a much wider range of research. Dignity denial, for example, is widespread among key populations for HIV and a range of other diseases even in the absence of macro-level social change, and indeed is widespread among the population at large [8, 9, 24–27]. The measures of cultural orientations and of male socio-sexual dominance likewise have wide applicability in the social and behavioral sciences. An earlier paper from this project showed that MSM were particularly likely to have their dignity attacked due to their race, [8] and our ideas about personal/cultural themes and orientations grew out of a review of our and others’ research on the HIV epidemic among African Americans [28]. Both of these earlier papers suggest that structural inequalities such as racism might be associated with the pathways discussed in this paper and thus that these pathways might be part of the causal mechanism connecting these macro-social factors with HIV.

In addition to their use in research, some of these measures may also be useful for social surveillance, particularly after Big Events happen in a country. Such use might help social or public health agencies to detect emerging problems like increases in high-risk drug use or sex trading early enough to forestall them or such effects as HIV or overdose epidemics.

Having said this, we also realize the incompleteness of this research. Given the number of measures we developed, we were unable to determine and measure optimal validators for them in advance, and even if we had, issues of questionnaire length restricted the number of questions we could ask. Thus, our validation efforts should be viewed as exploratory and to some degree prone to the error of falsely accepting them as validated due to our using several potential validators and accepting a scale as at least somewhat validated if any of these validators was correlated with the measure.

Table 4 presents a summary list of measures that seem worth using in further research, together with our summary judgement about the extent to which they are reliable and valid. Some of the measures do not meet our criteria for acceptable reliability and validity, but nonetheless we would recommend that further development of such measures be undertaken.

This study is subject to a number of limitations. Even if a measure is valid and reliable for these populations in New York at this time, cultural differences or historical change could make them less useful at other places or times. Some of the questions may have been subject to social desirability bias, and we had limited ability to assess this. Thus, we urge other researchers to attempt to validate these measures as they use them (or before), including investigating social desirability effects, so the field can get a sense of the extent to which they are reliable and valid in other contexts.

In addition, the sample is limited in that it is not a probability sample of these key populations, and indeed appears to be biased towards low income members of these populations. Also, on some items, such as some of those on group sex events, fewer than 100 participants responded (because they were not applicable to them, for example because they did not attend group sex events. This reduces confidence in the accuracy of the validation of those items. Beyond that, social reality is in many ways intersectional. Thus, although we developed these measures with MSM and at-risk heterosexuals (and PWID in an earlier paper) in mind, subsets by race/ethnicity, class and gender have different experiences. We incorporated this insight into our measures where we could, but have not in this paper pursued this issue systematically. Further research should investigate how and if these measures might be improved by making them specific to African American poor MSM as opposed to MSM in general. Further, some items asked of only one of the at-risk populations should perhaps have been included for the other. For example, MSM should have been asked about their numbers of female sex partners; and at-risk heterosexuals should have been asked about their community members’ stigma towards gay people. Finally, these measures should be considered as first steps in the development of a more polished set of measures in that, for given population groups and subgroups, more refined ways to phrase them might be appropriate. In such research, however, we would urge caution: Current wordings and scale development were based on a lengthy period of ethnographic research followed by discussion of how best to word the questions with MSM, at-risk heterosexuals and PWID.

Conclusions

Research into how Big Events and macrosocial interventions do or do not contribute to changes in public health relevant behaviors, networks and infection patterns has been retarded by lack of “Pathways Measures.” This paper has presented a number of such measures for use by the research community. We recommend using these measures and, in the process, improving them.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This research was supported by NIH Grants R01DA031597, P30DA011041, and DP1DA034989. The International AIDS Society (IAS) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse supported the post-doc fellowship of GN. We also acknowledge support from the University of Buenos Aires Grants UBACyT 20020130100790BA and UBACyT 20020100101021. The views presented in this paper represent only the authors and not the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02582-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflicts of interest The authors (Friedman, Samuel R; Pouget, Enrique R, Sandoval, Milagros; Rossi, Diana; Mateu-Gelabert, Pedro; Nikolopoulos, Georgios K; Schneider, John A; Smyrnov, Pavlo; Stall, Ron D) all declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research Involving Human Participants and Animals This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We use the term “at-risk heterosexuals” rather than “high-risk heterosexuals” because the risk comes from a dialectical mix of outside and personal influences and actions. There is a tendency to see the high risk of “high-risk heterosexuals” as a characteristic of the individual and thereby ignore both the sociocultural interactions that shape behaviors and practices and also the epidemiologic dynamics that affect whether their risk partners are or are not infected and infectious. Although an imperfect formulation, “at-risk heterosexual” can more easily call attention to this dialectic.

References

- 1.Friedman SR, Rossi D, Braine N. Theorizing “Big Events” as a potential risk environment for drug use, drug-related harm and HIV epidemic outbreaks. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SR, Sandoval M, Mateu-Gelabert P, Rossi D, Gwadz M, Dombrowski K, Smyrnov P, Vasylyeva T, Pouget ER, Perlman DC. Theory, measurement and hard times: some issues for HIV/AIDS research. AIDS Behav. 2013;7(6):1915–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Nikolopoulos GK, Mateu-Gelabert P, Rossi D, Smyrnov P, Jones Y, Friedman SR, et al. Developing measures of pathways that may link macro social/structural changes with HIV epidemiology. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:1808 10.1007/s10461-016-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikolopoulos G, Sypsa V, Bonovas S, Paraskevis D, Malliori-Minerva M, Hatzakis A, Friedman SR. Big events in greece and HIV infection among people who inject drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):825–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flom PL, Friedman SR, Jose B, Curtis R, Sandoval M. Peer norms regarding drug use and drug selling among household youth in a low income “drug supermarket” urban neighborhood. Drugs. 2001;8:219–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flom PL, Friedman SR, Jose B, Neaigus A, Curtis R. Recalled adolescent peer norms towards drug use in young adulthood in a low-income, minority urban neighborhood. J Drug Issues. 2001;31:425–43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawlowicz MP, Zunino SD, Rossi D, Touzé G, Wolman G, Bol-yard M, Sandoval M, Flom PL, Mateu-Gelabert P, Friedman SR. Drug use and peer norms among youth in a high-risk drug use neighborhood in Buenos Aires. Drugs. 2010;17(5):544–59. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Rossi D, Mateu-Gela-bert P, Nikolopoulos GK, Schneider JA, Smyrnov P, Stall RD. Interpersonal attacks on the dignity of members of HIV key populations: a descriptive and exploratory study. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(9):2561–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman S, Rossi D, Ralón G. Dignity denial and social conflicts. Rethink Marx. 2015;27(1):65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Jones Y, Mateu-Gelabert P. Formal and informal organizational activities of people who inject drugs in New York City: description and correlates. J Addict Dis. 2015;34(1):55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Jones Y, Nikolopoulos GK, Mateu-Gelabert P. Measuring altruistic & solidaristic orientations towards others among people who inject drugs. J Addict Dis. 2015;34:248–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biradavolu MR, Blankenship KM, Jena A, Dhungana N. Structural stigma, sex work and HIV: contradictions and lessons learnt from a community-led structural intervention in southern India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):95–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffries WL 4th, Gelaude DJ, Torrone EA, Gasiorowicz M, Oster AM, Spikes PS Jr, McCree DH, Bertolli J. Unhealthy environments, unhealthy consequences: experienced homonegativity and HIV infection risk among young men who have sex with men. Glob Public Health. 2015;7:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton A, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):465–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blankenship KM, Reinhard E, Sherman SG, El-Bassel N. Structural interventions for HIV prevention among women who use drugs: a global perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2):S140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latkin C, Donnell D, Celentano DD, Aramrattna A, Liu TY, Vongchak T, Wiboonnatakul K, Davis-Vogel A, Metzger D. Relationships between social norms, social network characteristics, and HIV risk behaviors in Thailand and the United States. Health Psychol. 2009;28(3):323–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latkin C, Donnell D, Liu TY, Davey-Rothwell M, Celentano D, Metzger D. The dynamic relationship between social norms and behaviors: the results of an HIV prevention network intervention for injection drug users. Addiction. 2013;108(5):934–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latkin CA. The phenomenological, social network, social norms, and economic context of substance use and HIV prevention and treatment: a poverty of meanings. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(8/9):1165–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner KD, Lankenau SE, Palinkas LA, Richardson JL, Chou CP, Unger JB. The perceived consequences of safer injection: an exploration of qualitative findings and gender differences. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(5):560–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. McGraw-Hill series in psychology In: Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH, editors. Psychometric theory, vol. xxiv 3rd ed New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. p. 752. [Google Scholar]

- 21.https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/nhbshet-2013.pdf and https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/nhbsmsm4-june2015.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 22.Friedman SR, Bolyard M, KhanM MC, Sandoval M, Mateu-Gela-bert P, Krauss B, Aral SO. Group sex events and HIV/STI risk in an Urban network. J Acq Immun Syn. 2008;49(4):440–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman SR, Williams L, Young AM, Teubl J, Paraskevis D, Kostaki E, Latkin L, German G, Mateu-Gelabert P, Guarino H, Vasylyeva TI, Skaathun B, Schneider J, Korobchuk A, Smyrnov P, Nikolopoulos G. Network research experiences in New York and Eastern Europe: Lessons for the southern U.S. in understanding HIV transmission dynamics. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep.2018;15(3):283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman SR. Alienated labor and dignity denial in capitalist society In: Berberoglu B, editor. Critical perspectives in sociology. Kendall/Hunt: Dubuque; 1991. p. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodson R Dignity at work. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson N Dignity and health: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson N Dignity & health. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman SR, Cooper HLF, Osborne A. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African-Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1002–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.