Abstract

The Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) gene SMN was recently duplicated (SMN1 and SMN2) in higher primates. Furthermore, invasion of the locus by repetitive elements almost doubled its size with respect to mouse Smn, in spite of an almost identical protein-coding sequence. Herein, we found that SMN ranks among the human genes with highest density of Alus, which are evolutionary conserved in primates and often occur in inverted orientation. Inverted repeat Alus (IRAlus) negatively regulate splicing of long introns within SMN, while promoting widespread alternative circular RNA (circRNA) biogenesis. Bioinformatics analyses revealed the presence of ultra-conserved Sam68 binding sites in SMN IRAlus. Cross-link-immunoprecipitation (CLIP), mutagenesis and silencing experiments showed that Sam68 binds in proximity of intronic Alus in the SMN pre-mRNA, thus favouring circRNA biogenesis in vitro and in vivo. These findings highlight a novel layer of regulation in SMN expression, uncover the crucial impact exerted by IRAlus and reveal a role for Sam68 in SMN circRNA biogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

The highly homologous SMN1 and SMN2 genes originate from a chromosome 5 repeat at the human 5q13.3 locus and encode for the essential Survival of Motor Neuron (SMN) protein (1,2). Loss of function mutations in SMN1 are linked to Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), a genetically inherited disease caused by deficiency in SMN protein expression and consequent degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord, progressive muscle weakness and atrophy (3,4). Although SMN2 potentially encodes the same protein, a silent C-to-T substitution in exon 7 impairs its inclusion in the mature mRNA and leads to transcripts encoding a truncated and highly unstable isoform (SMNΔ7) (5), which does not suffice SMN function. After substantial translational research efforts in the last decades, therapies eliciting clinical benefits for SMA patients have become available (6). The first FDA approved drug (Nusinersen) is an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) that restores SMN2 exon 7 splicing, thus ameliorating SMA phenotypes in mouse models and patients (7–9). Next, a gene therapy approach delivering the SMN1 gene through an adeno-associated viral vector was developed (10–12). Although both therapies provide significant clinical improvement, neither one represents a complete cure for SMA yet and not all patients respond equally to treatments. Thus, further understanding of SMN expression regulation may pave the ground for additional and more personalized therapeutic approaches.

The SMN1/2 (from hereafter referred to as SMN) locus undergoes extensive regulation, both at transcription and splicing levels (13). Furthermore, recent evidence indicates that the locus generates at least two antisense long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that impact on the sense SMN transcripts. Indeed, both lncRNAs were shown to repress transcription elongation within SMN through recruitment of the polycomb (PRC2) complex (14,15). Importantly, their knockdown by specific ASOs induced SMN expression and improved the efficacy of Nusinersen in SMA mice (14,15), suggesting that their regulation could be exploited to improve therapeutic strategies for SMA.

Another class of RNAs that can contribute to the regulation of protein-coding RNAs are the circular RNAs (circRNAs) (16). They are produced by back-splicing reactions in which a downstream 5′ splice site is covalently joint to an upstream 3′ splice site, thus causing circularization of the pre-mRNA (17,18). Since canonical splicing and back-splicing utilize the same pre-mRNA and are both operated by the spliceosome (19), they possibly compete with each other (16). Thousands of circRNAs have been discovered in eukaryotic cells and their expression is often regulated in a cell-type and stage-specific manner (20). Although the majority of circRNAs still lacks functional annotations, recent observations have revealed potentially important roles in gene regulation (17,18). The main mechanism favouring circRNA biogenesis is the presence of repetitive sequences in inverted orientation, and in particular inverted Alu repeats (21). Furthermore, dimerization of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) that recognize intronic regions, such as the STAR (Signal Transduction and Activation of RNA) protein QKI, was also shown to promote circRNA biogenesis (22,23). Nevertheless, whether RBPs exploit Alus to mediate this process is currently unknown.

Herein, we found that SMN rank among the top human genes for Alu density, many of which are present in inverted orientation. Strikingly, Alu pairing appears to interfere with splicing of long introns while driving widespread alternative circularization of the SMN pre-mRNA. We also found that the STAR protein Sam68 binds in proximity of Alus in the SMN pre-mRNAs and favours circRNA biogenesis. Our findings uncover a novel layer of regulation of the SMN locus with possible implications also for SMA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maintenance of type-I and type-II SMA mice

The SMA mouse models used were type-I FVB.Cg-Smn1tm1HungTg(SMN2)2Hung/J (005058) and type-II FVB.Cg-Tg(SMN2*delta7)4299Ahmb Tg(SMN2)89Ahmb Smn1tm1Msd/J (005025) (The Jackson Laboratory). Breeding and maintenance of mice were done in accordance with the institutional guidelines of the IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia and the approval of the Ethical Committee. This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Italian Ministry of Health. The protocol was approved by the Ministry of Health (permit no. 809_2015PR) and by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia. Every effort was made to minimize suffering of mice. Genomic DNA for genotyping was isolated from the tail by the Biotool™ Mouse Direct PCR Kit. Primers used for genotyping are listed in Supplementary Table S5.

Isolation and maintenance of murine hepatocytes harboring the human SMN2 transgene

Liver from P0 and/or P1 newborns (Smn+/+;SMN2++) were dissected, mechanically dissociated using a Potter glass homogenizer and plated at high density on collagen I (Transduction Laboratories) coated dishes in RPMI-1640 (Lonza), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 50 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 30 ng/ml insulin like growth factor II (PeproTech Inc), 10 mg/ml insulin (Roche), 2 mmol/l l-glutamine, 100 mg/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco). After 12–24 h, cultures were washed to remove all unattached cells, including red blood cells, and the medium was replaced. The cultures were maintained without transfer with medium replacement twice a week. Within 4 weeks the majority of cells died and within 6 weeks colonies with distinct cell morphology became visible and were isolated and propagated.

Cell culture and treatment

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) and human SMA type-I (GM03813) fibroblasts (Coriell Institute) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium Glutamax (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich) and Minimum Essential Medium + Glutamax (MEM, Gibco), respectively, at 37°C under 5% CO2. Culture media were supplemented with 10% (HEK293T) or 15% (GM03813) FBS (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco) and 5% non-essential amminoacids (Gibco).

For RNA stability, GM03813 cells were treated with increasing amount of LDC067 (Selleckchem) for 24 h, as indicated in the Supplementary Figure S2B. For ASO transfection, GM03813 cells were transduced by scraping delivery according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gene Tools) with 10 μM of ASO-E8 (5′ ATCAAGAAGAGTTACCCATTCCACT 3′) or control ASO (ASO-C) (5′ TCATTTGCTTCATACACAGG 3′). To label nascent SMN transcripts, cell were incubated with DRB (75 μM, Sigma Aldrich) and, after DRB removal, nascent RNAs were labelled by adding 2 mM of BrU (Sigma Aldrich) to the fresh medium for 60 min. Labelled transcripts were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg (for 5 μg of total RNA) of anti-BrdU antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and isolated as previously described (24).

Murine hepatocytes (2 × 105 cells/well) or human HEK293T cells (4 × 105 cells/well) were transfected with 250 ng of circSMN minigenes and/or 500 ng of Flag-Sam68 plasmid (when indicated) in six-well plates by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and Opti-MEM medium (Gibco) for 8 h. RNA and proteins were extracted 48 h after transfection.

RNA interference

siRNA oligonucleotides used for silencing the expression of DHX9 helicase and Sam68, hnRNP F/H and TIA-1 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Non-targeting scrambled siRNA was used as the negative control. All siRNA sequences utilized in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S5. A total of 40 × 104 cells/well were transfected with 100 pmol siRNA in six-well plates by using RNAi Max (Invitrogen) and Opti-MEM medium (Gibco). Transfection was repeated on two consecutive days to increase silencing efficiency. RNA and proteins were extracted 48 h after last transfection.

RT-PCR and qPCR analyses

Total RNA was extracted by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). After digestion with RNase-free DNase (Roche), 1/2 μg of total RNA was retro-transcribed with random primers using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) according to manufacturer's recommendations. 10% of cDNA was used as template for PCR (GoTaq, Promega) and reactions were analysed on 2% agarose gels. qPCR reactions were performed using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master and the LightCycler 480 System (Roche), according to manufacturer's instructions. RNase R (RNR07250, Epicentre) treatment was performed on 5–10 μg of total RNA (3U/μg of RNA) for 30′ at 37°C. Digested RNA was retro-transcribed as above. PCR products of interest were purified and sequenced (Eurofins Genomics). Primers used in RT-PCR and qPCR experiments are listed in Supplementary Table S5.

Western blot analyses

Total proteins were extracted from cells or murine tissues by using a lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 15 mM EGTA, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich), 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT. Extracted proteins were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels (10–20 μg/lane) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham). Blots were incubated with the indicated primary antibody in 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS plus 0.1% Tween-20 overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used (1:1000) were: rat anti-RNA polymerase II (phospho-CTD Ser-2) (Millipore), mouse anti-RNA polymerase II (N-20), rabbit anti-DHX9, mouse anti-GEMIN 2, mouse anti-ACTIN, rabbit anti-Sam68, mouse anti-hnRNP F/H and goat anti-TIA-1 (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-SMN (BD Biosciences). Detection was achieved using anti-rabbit, anti-mouse (GE Healthcare) and anti-rat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) HRP-linked secondary antibodies (1:10 000) and visualized by Immunocruz Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

UV-crosslinking immunoprecipitation

CLIP assays were performed as previously described (25). In brief, cells were irradiated on ice (100 mJ/cm2). Cell suspension was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min and the pellet was incubated for 10 min on ice in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and RNase inhibitor (Promega)). Samples were briefly sonicated and incubated with DNase (RNase-free; Ambion) for 3 min at 37°C and then centrifuged at 15 000g for 3 min at 4°C. For input RNA, 1 mg of extract was treated with Proteinase K for 30 min at 55°C and RNA was purified by standard procedure. For immunoprecipitation, 1 mg of extract was diluted to 1 ml with lysis buffer and incubated with rabbit anti-Sam68, mouse anti-hnRNP F/H and goat anti-TIA-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or IgGs (negative control) in the presence of protein G magnetic Dynabeads (Novox; Life Technologies). 1000 IU RNase I (Ambion) was added and reactions were incubated for 2 h at 4°C under rotation. After stringent washes (25), an aliquot (10%) was kept as a control of immunoprecipitation, while the rest was treated with 50 μg Proteinase K and incubated for 1 h at 55°C. RNA was then isolated by standard procedures.

Plasmid constructs

circSMN minigene was amplified (PCR primers listed in Supplementary Table S5) from Smn−/−;SMN2++ mouse genome and cloned in pCI vector (Promega). Briefly, tagged-exon 6 megaprimer was amplified using primers #1–2. Megaprimer and primer #3 were used to amplify 5′ end of circSMN minigene (E5-I6) that was digested with KpnI and SalI restriction enzymes and cloned in pCI vector (5′SMNcirc). 3′ end of circSMN (I6-3′dwr region) was amplified using primers #4–5. The 3′ end insert was digested with SalI and NotI restriction enzymes and cloned in the 5′SMNcirc vector digested with the same enzymes. Deletion of AluSq sequence in intron 5 was generated by amplifying the inserts #3–6 and #7–2. Deletion of Sam68 binding sites in intron 5 was generated by amplifying the inserts #3–8 and #9–2. Double deletion was generated by amplifying the inserts #3–6 and #9–2. All PCR amplicon generated for the deletion mutations were digested with KpnI and SalI restriction enzymes for subclining in pCI to generate pCI-SMNcirc vectors.

Bioinformatics analysis

Alu sequences coordinates were retrieved from the UCSC Genome Browser. Alu positions in SMN genes and links between pairs of Alus on opposite strands were plotted using R and R package igraph (v1.2.1). For conservation analysis of Alu elements in primates each subtype longest Alu sequence was aligned using T-Coffee tool (v11). The distance between the aligned sequences was computed using dnadist function from PHYLIP tool (v3.697). The distance matrices obtained were used to plot the dendrograms in R. For conservation analysis of SMN motifs within Alus, primate SMN sequences and 1500 flanking base pairs (bp) were retrieved from the UCSC Genome Browser. The motifs found in the human sequence were searched in the other SMN homologues using Blast tool from NCBI. For alignment of the three selected Alu motifs with all other Alu elements on opposite strand we used the pairwise alignment function from Biostring package in R and the identity matrix (Supplementary Tables S1–S4). For this analysis we also included a 3000 bp intergenic sequence on each side of the SMN gene.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantitative data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD), as indicated in the figure legends. Unpaired t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison post-test were performed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software). Power analysis was performed using the G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2).

RESULTS

Invasion of inverted repeat Alu elements characterizes the human SMN locus

Alus belong to the primate-specific Short Interspersed Elements (SINE) family of retrotransposons, are ∼300 nt long and account for up to 11% of the annotated human genome (26). During evolution, insertion of Alu elements in introns has represented a major difference between human and mouse SMN genes, which are instead highly conserved at the exon level (Figure 1A). Notably, whole genome comparison of Alu density highlighted SMN among the top-ranking human genes (Figure 1B). This feature was maintained also when only Alu-containing genes were considered (Figure 1B), or within protein-coding genes, which displayed significantly higher density of Alu elements than noncoding genes (P = 1.09e−53; Figure 1C). These observations indicate that the SMN locus has undergone a pervasive invasion of Alu elements upon evolution.

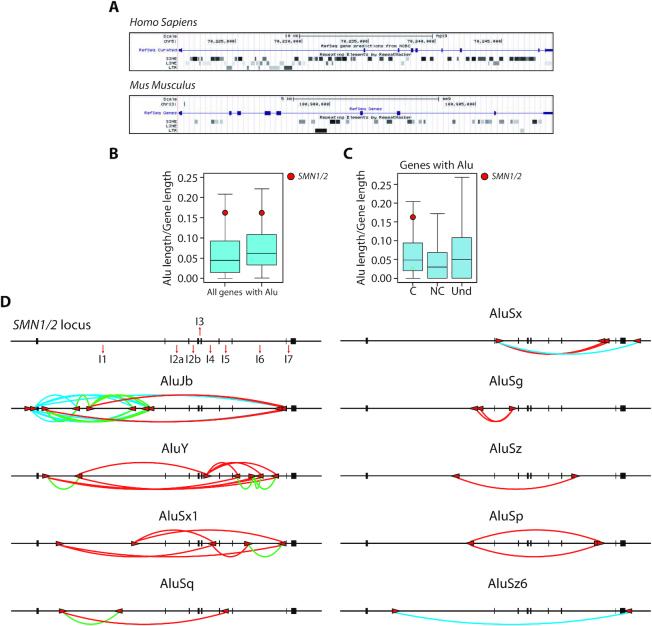

Figure 1.

Invasion of inverted repeat Alu elements characterizes the human SMN locus. (A) Graphic representation of non-LTR (SINE and LINE) and LTR elements in the human SMN1 and murine Smn gene (https://genome.ucsc.edu). (B, C) Box plots made with R (v3.2.3) represent the density of Alu elements in all human genes, only genes with Alu (B) in coding (C), non coding (NC) genes and in genes with undetermined function (Und) (C). The colored circle highlights the position of SMN genes. C versus NC P-value = 1.09e−53; C versus Und P-value = 3.49e−25; NC versus Und P-value = 1.50e−71. (D) Schematic representation of the human SMN locus with indicated the number of introns and position of Alus. SMN exons are indicated with black boxes. Alu elements are indicated with red arrows, the direction of the arrow indicates the orientation of the element. Red and green lines show the inter- and intra-intronic pairing between IRAlus, respectively. Blue lines show the pairing between intergenic and intronic regions.

We identified multiple Alu subtypes in the SMN locus, particularly the Jb, Y and Sx1, mapping to basically all introns with the exception of smallest introns (2b, 3 and 7). On the other hand, the longest SMN introns, intron 1 and 6, show the highest number of Alus (Figure 1D). AluJb elements were more frequent in intron 1, whereas AluY elements are predominantly located in intron 6. Furthermore, several Alus were also located in intergenic regions upstream and downstream of SMN (Figure 1D). Inspection of Alu orientation revealed the presence of several inverted repeats spanning the whole locus. On the basis of their sequence homology, we predicted that such inverted repeat Alus (IRAlus) could potentially mediate intra-intronic (in intron 1 and 6, Figure 1D, green lines), inter-intronic pairing (Figure 1D, red lines), as well as pairing with intergenic regions (Figure 1D, blue lines). Moreover, phylogenetic analyses indicated that SMN IRAlus are evolutionary conserved within primates (Supplementary Figure S1A). These observations suggest that Alu invasion of the primate SMN genes has added a new layer of regulation.

Inverted repeat Alus negatively impact on SMN transcript processing

Mounting evidence shows that Alus can modulate the expression of their ‘host’ genes at multiple layers, including transcription, splicing, export and translation (27). To investigate whether high Alu density impacts on transcription dynamics, we evaluated the processivity of the RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) by measuring the ratio between a distal and a proximal intron in human (SMN) and mouse (Smn) pre-mRNAs (28). To rule out differences potentially due to the cell or tissue context rather than to the gene under analysis, we analyzed transcripts expressed in mouse hepatocytes harboring the human SMN2 transgene (Supplementary Figure S1B, C). Quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) analyses revealed a striking reduction in RNAPII processivity in the human SMN compared to murine Smn gene (Figure 2A). Furthermore, we observed similar low RNAPII processivity in other human high-Alu genes (MARVELD2 and GOT2) with respect to low-Alu genes (CTDSP2 and POLI), which were all selected for length (∼30 kb) and number of exons (9–10) comparable with SMN (Figure 2B, C). By contrast, no substantial difference with the corresponding mouse orthologues was observed for human genes characterized by low Alu content (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S1D).

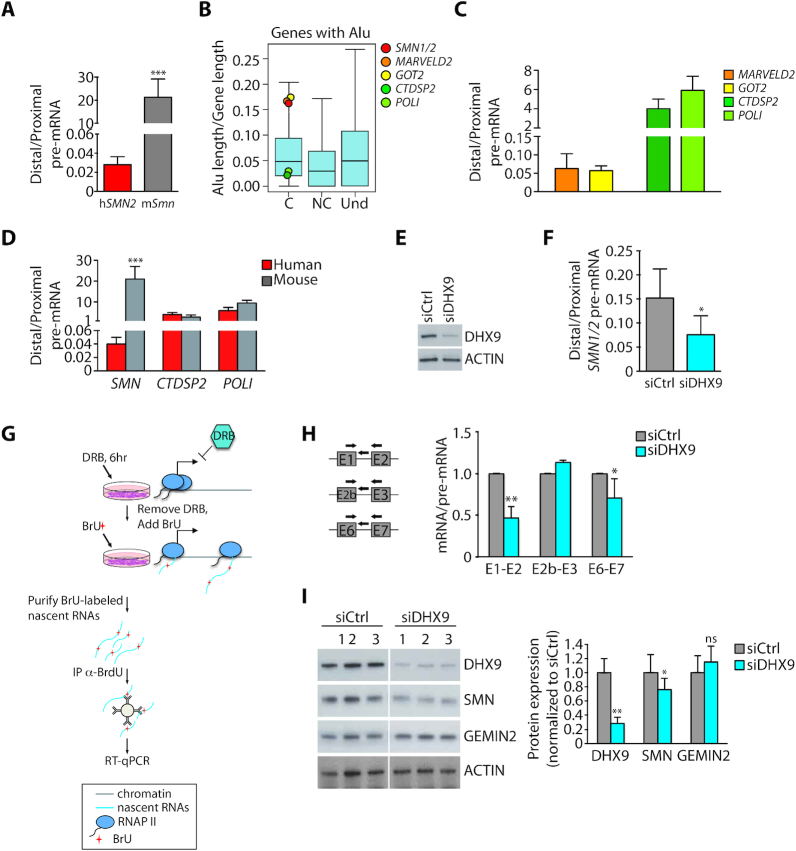

Figure 2.

Inverted repeat Alus negatively impact on SMN transcript processing. (A) qPCR analyses of the ratio between distal and proximal pre-mRNA region of human (hSMN2) and mouse (mSmn) SMN gene (mean ± SD, n = 5; ***P ≤ 0.001, unpaired t-test). The analysis was performed in hepatocytes isolated from liver of wild type mice (P1) harboring the human SMN2 transgene. (B) Box plots representing the density of the Alu elements in Alu-containing coding (C), non coding (NC) genes and in genes with undetermined function (Und). Boxplots were performed using R (v3.2.3). The red circle highlights the position occupied by SMN genes and other colored circles indicate the position occupied by high- (MARVELD2 and GOT2) and low-Alu (CTDSP2 and POLI) genes. (C) Bar graphs showing results of qPCR analyses of the ratio between distal and proximal pre-mRNA region of high- and low-Alu genes, as indicated (mean ± SD, n = 3). (D) Bar graphs showing results of qPCR analyses of the ratio between distal and proximal pre-mRNA region of SMN and low-Alu genes, as indicated. The analysis was performed by comparing human HEK293T and murine hepatocyte cell lines (mean ± SD, n = 3). (E) Western blot analysis of DHX9 in total extracts of DHX9-depleted cells (HEK293T). Actin was evaluated as loading control. (F) qPCR analyses of the ratio between distal and proximal pre-mRNA region of human SMN gene in DHX9-depleted cells (HEK293T) (mean ± SD, n = 5; *P ≤ 0.05; unpaired t-test). (G) A workflow for detection of BrU-labeled nascent RNAs. HEK293T cells silenced or not for DHX9 were treated with DRB for 6 h to block transcription and BrU-labeled newly synthesized total RNAs were collected 1 h after DRB removal. BrU-labeled nascent RNAs were purified by anti-BrdU antibody and subjected to RT-qPCR analysis. (H) qPCR analysis of nascent SMN transcripts labeled with BrU in DHX9-depleted cells (HEK293T). Novel transcripts were immunoprecipitated by using specific anti-BrdU antibody and analyzed with the indicated primers (left side). Cells not treated with BrU were used as control of the immunoprecipitation. The graph represents the ratio between mRNA versus pre-mRNA of specific SMN regions. The value of siCtrl cells was set as reference (mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01; unpaired t-test). (I) Representative images (left panel) and densitometry (right panel) of the western blot analyses of DHX9, SMN and GEMIN 2 expression in DHX9-depleted cells (HEK293T). Actin was evaluated as loading control (mean ± SD, n = 3; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ns not significant; unpaired t-test).

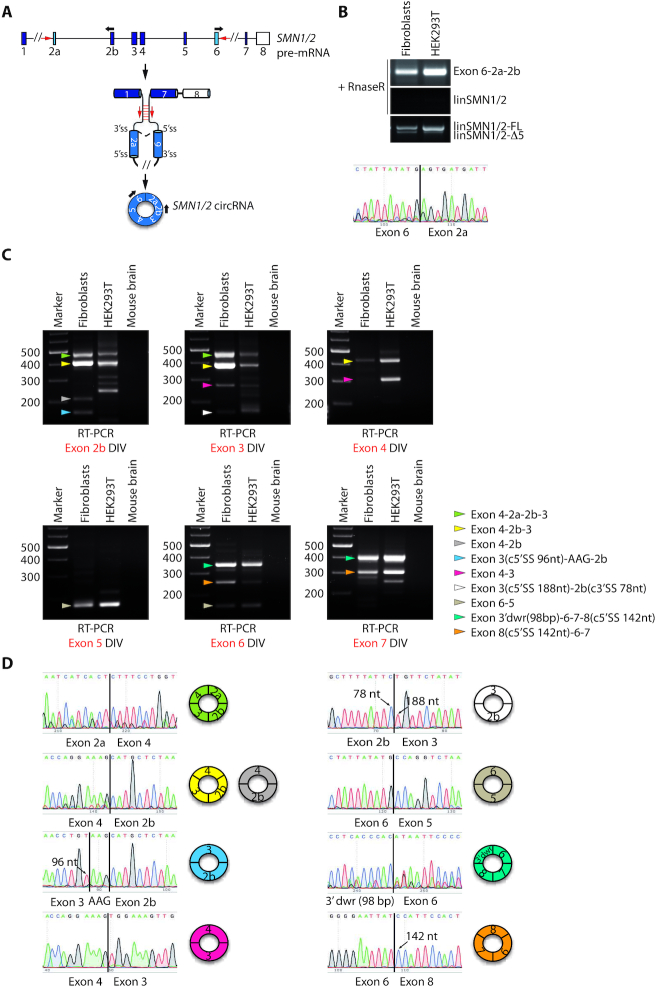

Figure 3.

The SMN pre-mRNA undergoes widespread alternative circularization. (A) Schematic representation of the human SMN pre-mRNA. Boxes represent exons, black lines represent introns. Exons in light blue (exon 2a and exon 6) represent the SMN circular RNA-forming exons and the white box indicates the last annotated exon of SMN. A circRNA is produced by back-splicing event joining the downstream 5′ donor site of exon 6 to upstream 3′ acceptor site of exon 2a. Black arrows indicate divergent oligonucleotide pairs utilized to amplify the SMN circRNA. Red arrows indicate the Alu elements contained in SMN intron 1 and intron 6 possibly involved in the circularization of SMN pre-mRNA. (B) Representative images of RT-PCR analyses for SMN circRNA (Exon 6-2a-2b) expression in human type-I SMA fibroblasts (GM03813) and HEK293T cells following RNAse R treatment. LinSMN1/2-FL and linSMN1/2-Δ5 stand for the linear counterpart of SMN transcripts containing or not the variable exon 5, respectively. The lower panel is the electropherogram showing the SMN circRNA-specific splice junction (indicated by a black bar) detected in the RT-PCR product. (C) Conventional PCR assays performed in human type-I SMA fibroblasts (GM03813) and in human HEK293T cells by using divergent (DIV) oligonucleotide pairs for each coding exon of SMN gene after RNAse R treatment. Mouse brain was used as negative control of PCR. Colored arrows indicate all sequenced SMN circRNAs; each color corresponds to a specific SMN circRNA whose exon composition is highlighted in the legend on the right. c5′ or c3′ SS stands for cryptic 5′ or 3′ splice site utilized for circularization. 3′dwr stands for 3′ downstream region indicating a cryptic exon of 98 bp involved in circularization and located downstream from the last annotated exon of SMN. (D) Electropherograms showing the circRNA-specific splice junction detected in the RT-PCR products. Splice junctions are indicated by a black bar. The nucleotide sequences of PCR products that apparently follow a linear exon number were obtained by using a reverse primer and correspond to a back-splice junction. On the right side, graphic representation of SMN circRNA containing that specific splice junction is illustrated. Arrows indicate the cryptic 3′ or 5′ SS involved in the back-splicing event and the nucleotide position that they occupy.

To test whether IRAlu pairing affected RNAPII processivity in SMN, we silenced DHX9, an RNA helicase that unfolds IRAlu pairs (29). Silencing of DHX9 further reduced RNAPII processivity in the SMN locus in human cells (Figure 2E, F), suggesting that increased Alu pairing interferes with transcription elongation and/or pre-mRNA processing. Accordingly, nascent RNA analysis performed by immunoprecipitation of pulse-labelled transcripts (Figure 2G) revealed that DHX9 knockdown reduced the splicing efficiency of Alu-rich introns (1 and 6), whereas it exerted no impact on splicing of the Alu-less intron 2b (Figure 2H). In line with lower RNA processing efficiency, DHX9 depletion was accompanied by significant reduction in SMN protein levels (Figure 2I). This effect was specific as expression of GEMIN 2, a component of the SMN complex, was unaffected in DHX9-depleted cells (Figure 2I). These observations indicate that modulation of IRAlu pairing could functionally impact on SMN expression.

The SMN pre-mRNA undergoes widespread alternative circularization

Pairing of IRAlus, especially when located in proximity of splice sites as in SMN (Figure 1D), may promote back-splicing events (21). In support of this notion, inspection of the deposited human circRNA sequences in Genome Browser (www.genome.ucsc.edu) revealed the existence of at least two SMN circRNAs, one containing exons 6 and 5 and the other containing exons 4, 2b and 3 (Supplementary Figure S2A). RNA circularization is generally favoured by pairing of long introns containing short and highly conserved inverted repeat sequences (30). Based on our bioinformatics analysis, pairing between intron 1 and 6, the longest introns in SMN, could be favoured by several IRAlus (Figure 1D), thus potentially favouring back-splicing between exon 6 and exon 2a (Figure 3A). To test this hypothesis, RNA from human type-I SMA fibroblasts (GM03813) and HEK293T cells was treated with RNAse R to degrade linear RNAs while preserving circRNAs (21). RT-PCR analyses using divergent primers in exon 2b and exon 6 identified a product of ∼300 bp (Figure 3B). Direct sequencing confirmed the back-splicing junction between exon 6 and exon 2a, indicating that this product originates from a circRNA (Figure 3B).

Due to their covalently closed conformation, circRNAs are relatively more stable than linear RNAs and tend to accumulate in cells (17,20). Accordingly, we found that transcriptional impairment with an inhibitor of RNAPII serine 2 phosphorylation (LDC067) did not affect the expression level of this SMN circRNA, while reducing the abundance of its linear counterpart (Supplementary Figure S2B). This result confirms the occurrence of a back-splicing event between exon 6 and exon 2a of SMN.

Since multiple potential IRAlu pairs were observed in the SMN locus, even within small size introns (Figure 2A), we asked whether the SMN pre-mRNA undergoes alternative circularization to produce multiple circRNA variants. RT-PCR analyses, using divergent oligonucleotide pairs for each SMN internal exon (with the exception of exon 2a for which we did not obtain reproducible results, data not shown), uncovered expression of numerous potential SMN circRNAs in both SMA fibroblasts and HEK293T cells (Figure 3C). Direct sequencing of these transcripts confirmed that they originate from back-splicing, it revealed that they utilize both canonical and cryptic splice sites (exons 2b, 3 and 8) for circularization and defined their alternative exon number and assortment (Figure 3C, D). We found that even the SMN last exon (exon 8), which does not contain a canonical 5′ splice site, is included in circRNAs. Indeed, sequencing analysis revealed that Exon 3′dwr-6-7-8 and Exon 8-6-7 circRNAs exploit a cryptic 5′ splice site located at nucleotide 143 of exon 8. This splice site either back-splices with exon 6 or it splices linearly with a cryptic exon located 169 bp downstream of exon 8 (3′dwr), which back-splices with exon 6 (Figure 3C, D). Based on circRNA abundance, SMN exon 4 and exon 6 are the most used exons in the back-splicing events that we identified (Figure 3C, D). This observation suggests a functional role of the Alu repeats contained in intron 4 (AluY, +295/+576 and AluSx1, +938/+1199; Figure 1D) and intron 5 (AluSq, +393/+671; Figure 1D) as key elements involved in SMN circRNAs biogenesis. In particular, our bioinformatics analysis of sequence complementarity suggests that intron 4 preferentially pairs with intron 1, intron 2a and intron 6, possibly mediating the formation of back-splice junctions 4-2a, 4-2b and 6-5, respectively. Likewise, intron 5 likely participates to the biogenesis of other two circRNAs (junctions 3′dwr-6 and 8-6) (Supplementary Figure S2C, Table S4). Notably, every SMN internal exon participates to circRNA biogenesis and even Alus contained in very short introns seem to be involved in the promotion of back-splicing events. These findings indicate that the SMN pre-mRNA undergoes widespread alternative circularization in human cells.

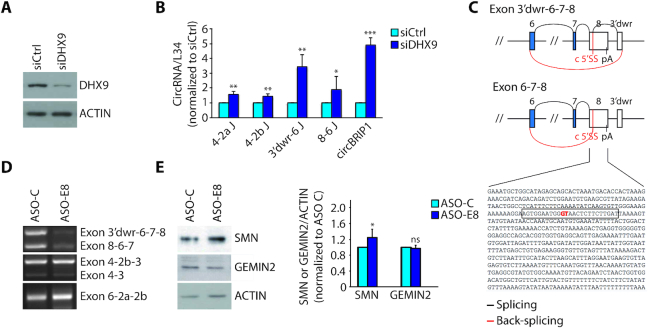

Interfering with SMN circRNAs biogenesis affects the expression of SMN protein

To investigate whether strengthening IRAlu pairing favours SMN circRNA biogenesis, we knocked down DHX9, which was previously reported to cause a global increase in circRNA biogenesis (29). As expected, depletion of DHX9 in HEK293T cells significantly increased the expression of SMN circRNAs (Figure 4A, B), as well as the control circBIRP1 (29). Since DHX9 depletion also caused a reduction in SMN protein expression (Figure 2I), we asked if limiting SMN circRNA biogenesis could lead to significant rescue of SMN protein expression. To evaluate this possibility by a simple, straightforward strategy, we focused on SMN circRNAs generated by back-splicing of a 5′ splice site not used for linear SMN splicing (Supplementary Figure S3A). The biogenesis of two exon 8-containing circRNAs employs a cryptic 5′ splice site embedded in exon 8 (Exon 3′dwr-6-7-8 and Exon 8-6-7; Figure 3C, D). Thus, we developed an ASO (ASO-E8) that masks this 5′ splice site (Figure 4C) and tested its efficacy in the modulation of exon 8-containing circRNAs. ASO-E8 administration in human SMA fibroblasts selectively reduced the target SMN circRNAs without impairing the production of other SMN circRNAs (Figure 4D). Furthermore, although this ASO targeted only a minority of circRNAs and did not significantly affect expression of SMN2 pre-mRNA (Supplementary Figure S3B), it caused a mild but significant rescue (∼20%) of SMN protein expression (Figure 4E). These results indicate that biogenesis of SMN circRNAs is targetable by ASO strategies and suggest that it competes with the protein-coding potential of the locus.

Figure 4.

Interfering with SMN circRNAs biogenesis affects the expression of SMN protein. (A) Western blot analysis of DHX9 in DHX9-depleted cells (HEK293T). Actin was evaluated as loading control. (B) qPCR analysis for indicated back-splice junctions in DHX9-depleted cells (HEK293T). CircBRIP1, known to be regulated by DHX9 (29), was used as positive control. RPL34 was used to normalize RNA content in parallel RT-PCR reactions omitting RNAse R treatment (mean ± SD, n = 3; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; unpaired t-test). (C) Schematic representation of splicing and back-splicing events that generate the two exon 8-containing SMN circRNA, as indicated in the figure. Exons are represented as boxes and introns as lines. In blue and in white are indicated the coding and the non-coding exons, respectively. Shown below is the nucleotide sequence of SMN exon 8 and in red is indicated the cryptic 5′ splice site (c 5′SS) involved in the back-splicing event with the 3′ splice site of exon 6. The sequence of ASO-E8 is highlighted in the rectangle. pA stands for poly A site and 3′dwr stands for 3′ downstream region indicating a cryptic exon of 98 bp involved in circularization and located downstream from exon 8 of SMN. (D) Representative images of RT-PCR analysis for the indicated SMN2 circRNAs in ASO treated cells (GM03813). ASO-C is a control morpholino. (E) Representative images (left panel) and densitometry (right panel) of western blot for SMN and GEMIN 2 in ASO treated cells (GM03813). Actin was evaluated as loading control (mean ± SD, n = 5; *P ≤ 0.05, ns not significant; unpaired t-test).

Sam68 binds Alu-rich introns in SMN and promotes pre-mRNA circularization

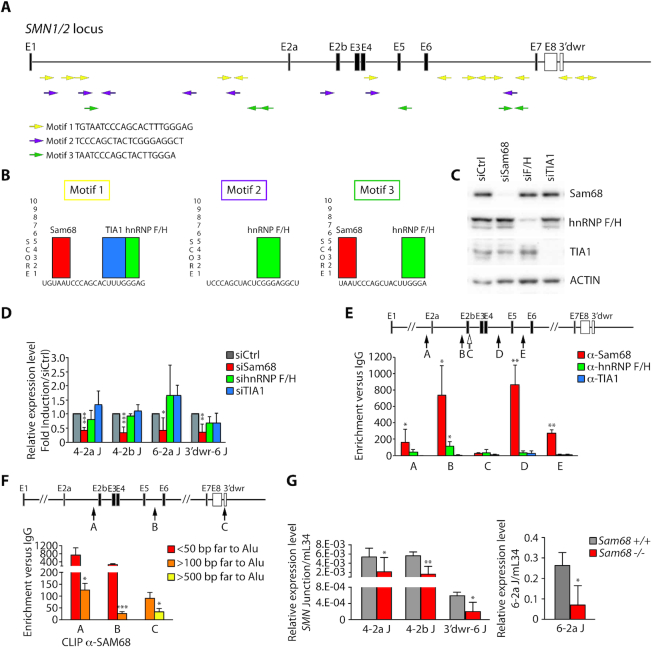

Short and highly conserved inverted repeat sequences are sufficient to stabilize RNA secondary structures and to promote circRNA biogenesis (30). In depth analysis of SMN IRAlus identified 228 highly conserved (100% identity) short sequences (25–53 bp) that occur at least once in inverted orientation in SMN (Supplementary Table S1) and are significantly conserved in other primates (92–100% identity) but not in mouse Smn (Supplementary Table S2). Three core sequences are particularly abundant and repeated multiple times in inverted orientation along the gene and downstream of the last SMN exon (Figure 5A; Supplementary Table S3). Moreover, ∼50% of these ultra-conserved motifs map to AluY, Sx1 and Sq (Supplementary Figure S4) and these Alu elements flank exons that more frequently participate to biogenesis of the circRNAs detected in our experiments (exon 4 and exon 6, see Figure 3C, D). Thus, the higher propensity of these Alu elements to pair may be related to the high abundance of such ultra-conserved motifs.

Figure 5.

Sam68 binds Alu-rich introns in SMN and promotes pre-mRNA circularization. (A) Graphic representation of the human SMN locus. Exons are indicated with black boxes and introns with lines. Colored arrows represent the identified conserved motifs within Alu elements. Their orientation is indicated by the direction of the arrow. The nucleotide sequences of the three motifs are indicated. (B) Predicted binding sites for Sam68, hnRNP F/H and TIA1 were identified (SpliceAid: database of RNA-Splicing Proteins binding). (C) Western blot analysis for indicated proteins in Sam68-, hnRNP F/H- and TIA1-depleted cells (HEK293T). Actin was evaluated as loading control. (D) qPCR analysis for indicated back-splice junctions in Sam68-, hnRNP F/H- and TIA1-depleted cells (HEK293T). RPL34 was used to normalize for RNA content in parallel RT-PCR reactions omitting RNAse R treatment (mean ± SD, n = 3/5; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; unpaired t-test). (E, F) CLIP assay of Sam68 (E, F), hnRNP F/H (E) and TIA-1 (E) binding to the SMN pre-mRNA. HEK293T cells were UV-crosslinked and immunoprecipitated with control IgGs or antibodies, as indicated. The bar graph shows qPCR signals amplified in CLIP assays expressed as enrichment versus IgG. The value of IgGs was set as 1. The upper panel shows a schematic representation of SMN gene structure and the Alu-overlapping regions amplified by qPCR are indicated with black arrows. The white arrow in panel E indicates the amplified region across exon 2b–intron 2b junction that does not contain Alus (mean ± SD, n = 6; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; unpaired t-test). (G) qPCR analysis for the indicated SMN2 back-splice junctions in cerebellum of adult Sam68 wild type (Sam68+/+) and knockout mice (Sam68−/−) harboring the human transgene SMN2++. Murine L34 (mL34) was used to normalize for RNA content (mean ± SD, n = 3/6; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01; unpaired t-test).

Since RBPs that recognize intronic regions, such as QKI, were shown to promote circRNA biogenesis (22,23), we searched for RBP-specific motifs within these sequences. We identified strong binding sites for four RBPs: Sam68, TIA-1 and hnRNP F/H (Figure 5B). Two of these (Sam68 and TIA-1) also regulate splicing of the disease-associated SMN2 exon 7 (31–33). Knockdown experiments in HEK293T cells (Figure 5C) indicated that depletion of Sam68 caused a significant reduction in the expression of several SMN circRNAs, whereas TIA-1 and hnRNP F/H silencing exerted no significant effect (Figure 5D).

Sam68 is a homolog of QKI and binds to RNA as a dimer (34), thus displaying key features required to stabilize intronic pairing and to promote circRNA biogenesis (22,23). To test whether Sam68 actually binds SMN pre-mRNA in proximity of Alus, we performed UV crosslink immunoprecipitation (CLIP) experiments. Strikingly, strong binding of Sam68 was observed in close proximity of Alus containing motifs 1 and 3 sequences, whereas hnRNP F/H bound weakly and TIA-1 binding was barely detectable (Figure 5E). Sam68 CLIP signals map to Alus located in proximity of splice sites that are well-positioned to promote back-splicing of exon 4 with exon 2a or exon 2b and of exon 8 with exon 6. Notably, Sam68 binding near these Alus was promoted by depletion of DHX9 (Supplementary S5A), thus correlating with increased SMN circRNA production (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we observed that Sam68 CLIP signals gradually decreased when qPCR primers were positioned at further distance from Alus (Figure 5F). These observations indicate that Sam68 preferentially binds in proximity of Alu-rich regions in SMN introns.

We previously reported that knockout of Sam68 in SMA mice rescued SMN2 exon 7 splicing, SMN protein expression and ameliorated the SMA phenotype (31). To evaluate the production of SMN circRNAs in a physiological context, we analysed their expression in a mouse model of SMA (SMN2Δ7;SMN2++;Smn+/−) that is either wild type or knockout for the Sam68 gene (31). qPCR analyses using primers specific for the circular splice junctions 4-2a, 4-2b, 6-2a and 3′dwr-6 indicated that circRNAs are produced by the human SMN2 gene in various brain regions, with maximal expression in the cerebellum (Supplementary Figure S5B-E). Each SMN circRNA represented a small percentage (0.035–1.3%) of linear SMN2 transcript in vivo (Supplementary Figure S5F), with no significant differences in their expression between wild type and SMA mice (Supplementary Figure S5G). Importantly, Sam68 is also expressed at higher levels in cerebellum with respect to other brain regions (35), suggesting that it may be implicated in SMN circRNA biogenesis in this brain region. In line with this hypothesis, we observed that knockout of the Sam68 gene in the same mouse background caused a significant reduction of all three SMN circRNAs tested (Figure 5G). These findings support a new role for Sam68 in SMN circRNA biogenesis.

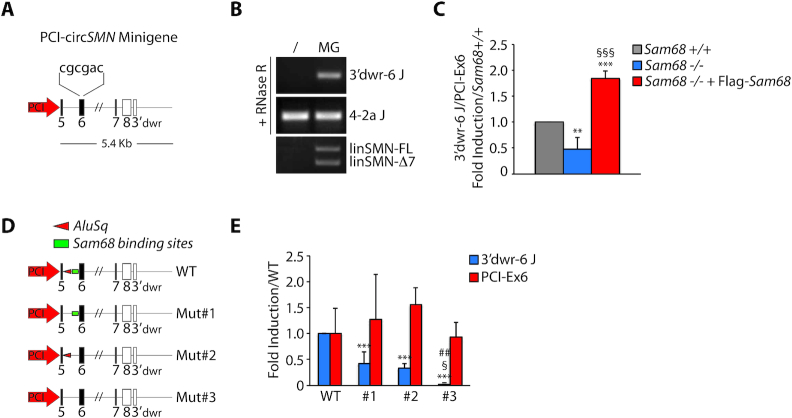

Sam68 cooperates with IRAlu-rich introns in SMN circRNA biogenesis

Sam68 recognizes single-strand A/U-rich bipartite motifs as a dimer in target transcripts (36,37). Since such high-affinity binding sites were also very abundant in the regions flanking the Alus, we hypothesized that Sam68 binding to these Alu-proximal regions and its homodimerization may contribute to bring in close proximity IRAlus that are located in distant introns, thus favoring circRNA biogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a minigene encompassing the SMN coding region from exon 5 to the region downstream of exon 8, comprising the cryptic exon (3′dwr) that back-splices with exon 6. An internal portion of intron 6 was deleted to reduce the size of the minigene, while a six-nucleotide tag was inserted in exon 6 to allow discrimination of the recombinant RNA products from endogenous transcripts (Figure 6A). Transfection of the minigene in HEK293T cells resulted in the production of the expected 3′dwr-6-7-8 circRNA (Figure 6B), indicating that it is suitable to study SMN circRNA biogenesis. Importantly, transfection in hepatocytes that are either wild type or knockout for Sam68 indicated that this minigene-derived SMN circRNA is sensitive to Sam68 expression, as its production was reduced in knockout cells and rescued by transfection of recombinant Flag-Sam68 (Figure 6C). Next, we performed deletion mutagenesis of intron 5 to eliminate either the Alu or a downstream flanking region enriched in Sam68 binding sites (Figure 6D). Both deletions caused a significant reduction of 3′dwr-6-7-8 circRNA expression (Figure 6E). However, concomitant deletion of both the Alu and the Sam68 binding region elicited an additive effect and almost completely abolished circularization (Figure 6E). Neither deletion impaired linear splicing of exon 6, indicating that these mutations did not disrupt the 3′ splice site at the intron 5–exon 6 junction. These results suggest that Sam68 cooperates with IRAlu pairing to promote circularization of the SMN pre-mRNA.

Figure 6.

Sam68 cooperates with IRAlu-rich introns in SMN circRNA biogenesis. (A) Schematic representation of circSMN minigene. Boxes represent exons, black lines represent introns and the white boxes indicate the non-coding exons of SMN. The nucleotide sequence indicates the six nucleotide TAG inserted into the SMN exon 6. (B) Representative image of RT-PCR analysis for minigene-derived SMN back-splice junction (3′dwr-6 J) in HEK293T transfected with empty vector (/) or with circSMN minigene (MG). linSMN-FL and linSMN-Δ7 stand for linear SMN transcripts full length or exon 7 skipped, respectively. (C) qPCR analysis for the minigene-derived SMN back-splice junction (3′dwr-6 J) in Sam68 wild type (Sam68+/+), knockout hepatocytes (Sam68−/−) and knockout hepatocytes reconstituted with Flag-SAM68 (Sam68−/− + Flag-Sam68). The linear transcript encoded by the minigene (PCI-Ex6) was used to normalize for RNA content (mean ± SD, n = 3; **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 (Sam68+/+ versus Sam68−/− or Sam68−/− + Flag-Sam68); §§§P ≤ 0.001 (Sam68−/− versus Sam68−/− + Flag-Sam68); one-way ANOVA). (D) Schematic representation of mutant circSMN minigenes used. Mut#1, #2 and #3 stand for deletion mutant #1, #2 and #3, respectively. WT stands for wild type minigene. (E) qPCR analysis for the minigene-derived SMN back-splice junction (3′dwr-6 J) in hepatocytes wild type. The 3′dwr-6 junction was normalized with PCI-Ex6 amplicon as in (C). Murine L34 was used to normalize for RNA content (mean ± SD, n = 3; ***P ≤ 0.001 (WT versus Mut#1 or #2 or #3); §p ≤ 0.05 (Mut#1 versus Mut#3); ##P ≤ 0.01 (Mut#2 versus Mut#3); one-way ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

The human SMN locus is almost twice the size of the mouse Smn locus and much of this difference is caused by an extensive invasion of Alu elements that has occurred upon evolution. Due to such pervasive insertion of Alu elements, human SMN ranks among the genes with the highest Alu density, many of which are present in inverted orientation (IRAlus). Alus can impact on several layers of host gene regulation, ranging from transcription to translation (27). Here, we show that IRAlus negatively affect RNAPII transcriptional dynamics and pre-mRNA processing within SMN, thus likely reducing the transcriptional potential of the locus. Furthermore, IRAlus promote alternative back-splicing events, yielding multiple circRNAs. Knockdown of DHX9, a helicase which destabilizes IRAlu paring and represses circRNA biogenesis (29), further reduced the processing of Alu-rich introns in the SMN locus and increased the concentration of SMN circRNAs, suggesting that a delay in intron splicing may offer a window of opportunity for pairing of distal introns through IRAlus and promotion of back-splicing events. These findings support a role of IRAlus as key regulatory determinants of SMN expression in primates, which may have implications in neurodegenerative diseases linked to reduced SMN function (4).

For many human genes just one or few circRNAs have been described, suggesting the involvement of a limited number of exons that are generally flanked by long introns (17,18). By contrast, our results indicate that the SMN pre-mRNA undergoes alternative back-splicing regulation to generate many circRNAs characterized by variable exon number and assortment, with virtually every exon participating to circRNA biogenesis. Sequencing analysis indicated that, in addition to the involvement of canonical splice sites, SMN circRNAs also originate from back-splicing of cryptic splice sites. For instance, the biogenesis of two SMN circRNAs (Exon 3′dwr-6-7-8 and Exon 8-6-7) employed a cryptic 5′ splice site embedded in exon 8, which is the last annotated exon in linear SMN mRNA. Noteworthy, Exon 3′dwr-6-7-8 and Exon 8-6-7 SMN circRNAs include the variable exon 7 also in SMA fibroblasts (GM03813), whereas this exon is skipped in 85–90% of linear SMN2 transcripts (4). This observation suggests that splicing of SMN2 exon 7 is differentially regulated in linear and circular transcripts. It will be interesting to investigate whether its preferential inclusion in circRNAs may contribute to limiting full-length expression of SMN2 linear mRNA.

While two of the identified SMN circRNAs (i.e. hsa_circ_0002251 and hsa_circ_0072853) were previously annotated in the online repository circBase (http://www.circbase.org), our work highlights the widespread nature of SMN pre-mRNA circularization and suggests the functional impact of this process in the regulation of the locus. While our manuscript was in preparation, similar findings were reported by another study, which also describes extensive circRNA biogenesis from the SMN locus (38). Notably, all the circRNAs that we have identified were also found in this other study, indicating that these molecules are not random by-products, but rather their detection and isolation is highly reproducible from multiple cell lines using various experimental approaches. For this reason, SMN circRNAs could represent good candidates as biomarkers in SMA patients. Since a role for SMN in transcriptional termination control has been described (39), it is conceivable that SMN circRNAs extending beyond the canonical last exon 8 are preferentially expressed in the body fluids of SMA patients, in which SMN expression is very low. Thus, they might represent a valid parameter to predict the onset and the progression of disease and to stratify SMA patients that exhibit different responses to therapy in spite of similar or identical genetic diagnosis.

Our work shows that even Alus contained in very short introns are active in SMN circRNA biogenesis. Indeed, we observed that exon 4 and 6 are most frequently involved in SMN back-splicing events, suggesting that IRAlus contained in the flanking introns (AluY and AluSx1 in intron 4, AluSq in intron 5) are particularly prone to pairing, which may be related to the high representation of the short ultra-conserved sequences in these elements. Most SMN circRNAs identified herein belong to two groups: a proximal group containing exons 2a-4 (SMN circRNAs Exon 4-2a-2b-3, Exon 4-2b-3 and Exon 4-2b) that utilizes intron 4 pairing with upstream introns and a distal group containing exons 5-8 that utilizes pairing of intron 4 with intron 6 (SMN circRNA Exon 6-5) or of intron 5 with the intergenic region (3′dwr) located downstream of exon 8 (SMN circRNAs Exon 3′dwr-6-7-8 and Exon 8-6-7). Thus, these intronic SMN regions appear to contribute alternative secondary structures that are likely to impact on the regulation of pre-mRNA processing.

Mounting evidence supports the hypothesis that insertion of Alu elements in SMN has added additional layers of gene regulation upon evolution. In addition to the Alu-dependent transcriptional (RNAPII processivity) and post-transcriptional (intron splicing) regulation described in our study, exonization of an Alu element in intron 6 (exon 6B) was shown to augment the transcript variants produced by human SMN (40,41). Interestingly, exon 6B-containing SMN transcripts encode for a protein (SMN6B) that is less stable than the full-length SMN. Thus, elucidating the molecular mechanism by which the presence of Alu elements modifies the protein-coding potential of the SMN genes may provide additional targets to enhance SMN2 expression in SMA cells and animal models. In this regard, our study shows that repression of a small percentage of circRNAs exerts a mild but significant impact on SMN expression. We designed an ASO (ASO-E8) to target the cryptic 5′ splice site in SMN exon 8, thus interfering with the expression of two exon 8-containing circRNAs (Exon 3′dwr-6-7-8 and Exon 8-6-7). Since ASO-E8 administration specifically repressed the expression of these SMN circRNAs and slightly increased SMN protein expression, pre-mRNA circularization and/or other Alu-mediated mechanisms may directly affect SMN expression. Indeed, it is also possible that the numerous Alu elements contained in the SMN promoter and 3′ untranslated regions contribute to regulation of transcription, stability and translation of SMN transcripts.

Bioinformatics analyses highlighted three short sequences (23–25 bp) within SMN Alus that are ultra-conserved in primates and occur multiple times in inverted orientation within the locus. Their orientation and proximity to splice sites suggested to us that they may promote alternative back-splicing events. Indeed, short inverted sequences are sufficient to promote intron pairing and pre-mRNA circularization (30). Since some RBPs can promote circRNA biogenesis by binding to intronic regions and facilitating their pairing through homo- or hetero-dimerization (22,23), we searched for RBP motifs enriched within these ultra-conserved sequences. The analysis identified strong binding sites for Sam68, TIA-1 and hnRNP F/H. Of these RBPs, only Sam68 appeared to play a role in SMN circRNA biogenesis and its effect seems to be direct. Sam68 strongly binds the SMN pre-mRNA in proximity of intronic Alu elements and its knockdown significantly reduces the expression of SMN circRNAs. Since Sam68 binding to RNA requires its dimerization (34), this RBP is well suited to promote looping between introns and to contribute to circRNAs biogenesis, by bringing close to each other back-splice sites that would otherwise be distant. Thus, Sam68 dimerization may cooperate with IRAlu pairing to bring intronic regions in close proximity. In support of this hypothesis, our mutagenesis studies indicate that deletion of the Alu in intron 5, or of the Sam68 binding sites downstream of it, caused a significant reduction of the 3′dwr-6-7-8 circRNA. Furthermore, combined deletion of these intronic elements almost completely abolished circRNA biogenesis, thus suggesting a cooperative action of the Alu and Sam68 to promote SMN pre-mRNA circularization. As Alus show a high degree of conservation in the human genome, it is conceivable that Sam68 might have a more general role in circRNA biogenesis in human cells. It is also interesting that almost half of the Sam68-bound short ultra-conserved motifs map to younger Alu elements (42). Thus, Sam68, as well as other RBPs regulating the biogenesis of such circRNAs, may have only recently acquired new regulatory functions. Since circRNAs accumulate in brain with ageing (43) and their dysregulation possibly contributes to neurodegenerative diseases (44), modulating their expression in the brain may have both physiological and pathological consequences.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data that support the finding of this study are available from corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Chiara Naro for fruitful discussion throughout this work and helpful suggestions and Dr Eleonora Cesari for technical assistance. We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Maria Paola Paronetto and Dr Ramona Palombo for DHX9 reagents and helpful discussion and to Dr Tonino Alonzi for technical assistance and support in the isolation and maintenance of murine hepatocytes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) [IG18790 to C.S.]; Telethon [GGP14095 to C.S.]; Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR) [PRIN 2018 to C.S.]; Italian Ministry of Health [GR-2018-12365706 to V.P.]. Funding for open access charge: Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC); Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR); Italian Ministry of Health.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schmutz J., Martin J., Terry A., Couronne O., Grimwood J., Lowry S., Gordon L.A., Scott D., Xie G., Huang W. et al.. The DNA sequence and comparative analysis of human chromosome 5. Nature. 2004; 431:268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lefebvre S., Burglen L., Reboullet S., Clermont O., Burlet P., Viollet L., Benichou B., Cruaud C., Millasseau P., Zeviani M. et al.. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995; 80:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nurputra D.K., Lai P.S., Harahap N.I., Morikawa S., Yamamoto T., Nishimura N., Kubo Y., Takeuchi A., Saito T., Takeshima Y. et al.. Spinal muscular atrophy: from gene discovery to clinical trials. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2013; 77:435–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnold W.D., Burghes A.H.. Spinal muscular atrophy: development and implementation of potential treatments. Ann. Neurol. 2013; 74:348–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cho S., Dreyfuss G.. A degron created by SMN2 exon 7 skipping is a principal contributor to spinal muscular atrophy severity. Genes Dev. 2010; 24:438–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sumner C.J., Crawford T.O.. Two breakthrough gene-targeted treatments for spinal muscular atrophy: challenges remain. J. Clin. Invest. 2018; 128:3219–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finkel R.S., Chiriboga C.A., Vajsar J., Day J.W., Montes J., De Vivo D.C., Yamashita M., Rigo F., Hung G., Schneider E. et al.. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: a phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet. 2017; 388:3017–3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hua Y., Sahashi K., Rigo F., Hung G., Horev G., Bennett C.F., Krainer A.R.. Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature. 2011; 478:123–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh N.N., Howell M.D., Androphy E.J., Singh R.N.. How the discovery of ISS-N1 led to the first medical therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. Gene Ther. 2017; 24:520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dominguez E., Marais T., Chatauret N., Benkhelifa-Ziyyat S., Duque S., Ravassard P., Carcenac R., Astord S., Pereira de Moura A., Voit T. et al.. Intravenous scAAV9 delivery of a codon-optimized SMN1 sequence rescues SMA mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011; 20:681–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Foust K.D., Wang X., McGovern V.L., Braun L., Bevan A.K., Haidet A.M., Le T.T., Morales P.R., Rich M.M., Burghes A.H. et al.. Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010; 28:271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12. Valori C.F., Ning K., Wyles M., Mead R.J., Grierson A.J., Shaw P.J., Azzouz M.. Systemic delivery of scAAV9 expressing SMN prolongs survival in a model of spinal muscular atrophy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010; 2:35ra42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh R.N., Singh N.N.. Mechanism of splicing regulation of spinal muscular atrophy genes. Adv. Neurobiol. 2018; 20:31–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. d’Ydewalle C., Ramos D.M., Pyles N.J., Ng S.Y., Gorz M., Pilato C.M., Ling K., Kong L., Ward A.J., Rubin L.L. et al.. The antisense transcript SMN-AS1 Regulates SMN Expression and is a novel therapeutic target for spinal muscular atrophy. Neuron. 2017; 93:66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woo C.J., Maier V.K., Davey R., Brennan J., Li G., Brothers J. 2nd, Schwartz B., Gordo S., Kasper A., Okamoto T.R. et al.. Gene activation of SMN by selective disruption of lncRNA-mediated recruitment of PRC2 for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. PNAS. 2017; 114:E1509–E1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ashwal-Fluss R., Meyer M., Pamudurti N.R., Ivanov A., Bartok O., Hanan M., Evantal N., Memczak S., Rajewsky N., Kadener S.. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell. 2014; 56:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen L.L. The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nat Rev. Mol Cell Biol. 2016; 17:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilusz J.E. A 360 degrees view of circular RNAs: from biogenesis to functions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. RNA. 2018; 9:e1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Starke S., Jost I., Rossbach O., Schneider T., Schreiner S., Hung L.H., Bindereif A.. Exon circularization requires canonical splice signals. Cell Rep. 2015; 10:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen W., Schuman E.. Circular RNAs in brain and other tissues: a functional enigma. Trends Neurosci. 2016; 39:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang X.O., Wang H.B., Zhang Y., Lu X., Chen L.L., Yang L.. Complementary sequence-mediated exon circularization. Cell. 2014; 159:134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conn S.J., Pillman K.A., Toubia J., Conn V.M., Salmanidis M., Phillips C.A., Roslan S., Schreiber A.W., Gregory P.A., Goodall G.J.. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell. 2015; 160:1125–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li X., Yang L., Chen L.L.. The Biogenesis, Functions, and challenges of circular RNAs. Mol. Cell. 2018; 71:428–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cappellari M., Bielli P., Paronetto M.P., Ciccosanti F., Fimia G.M., Saarikettu J., Silvennoinen O., Sette C.. The transcriptional co-activator SND1 is a novel regulator of alternative splicing in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014; 33:3794–3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bielli P., Sette C.. Analysis of in vivo interaction between RNA binding proteins and their RNA targets by UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) method. Bio-protocol. 2017; 7:e2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lander E.S., Linton L.M., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W. et al.. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001; 409:860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen L.L., Yang L.. ALUternative regulation for gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 2017; 27:480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Batsche E., Yaniv M., Muchardt C.. The human SWI/SNF subunit Brm is a regulator of alternative splicing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006; 13:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aktas T., Avsar Ilik I., Maticzka D., Bhardwaj V., Pessoa Rodrigues C., Mittler G., Manke T., Backofen R., Akhtar A.. DHX9 suppresses RNA processing defects originating from the Alu invasion of the human genome. Nature. 2017; 544:115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang D., Wilusz J.E.. Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes Dev. 2014; 28:2233–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pagliarini V., Pelosi L., Bustamante M.B., Nobili A., Berardinelli M.G., D’Amelio M., Musaro A., Sette C.. SAM68 is a physiological regulator of SMN2 splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. J. Cell Biol. 2015; 211:77–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedrotti S., Bielli P., Paronetto M.P., Ciccosanti F., Fimia G.M., Stamm S., Manley J.L., Sette C.. The splicing regulator Sam68 binds to a novel exonic splicing silencer and functions in SMN2 alternative splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. EMBO J. 2010; 29:1235–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singh N.N., Seo J., Ottesen E.W., Shishimorova M., Bhattacharya D., Singh R.N.. TIA1 prevents skipping of a critical exon associated with spinal muscular atrophy. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011; 31:935–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen T., Damaj B.B., Herrera C., Lasko P., Richard S.. Self-association of the single-KH-domain family members Sam68, GRP33, GLD-1, and Qk1: role of the KH domain. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997; 17:5707–5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. La Rosa P., Bielli P., Compagnucci C., Cesari E., Volpe E., Farioli Vecchioli S., Sette C.. Sam68 promotes self-renewal and glycolytic metabolism in mouse neural progenitor cells by modulating Aldh1a3 pre-mRNA 3′-end processing. eLife. 2016; 5:e20750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feracci M., Foot J.N., Grellscheid S.N., Danilenko M., Stehle R., Gonchar O., Kang H.S., Dalgliesh C., Meyer N.H., Liu Y. et al.. Structural basis of RNA recognition and dimerization by the STAR proteins T-STAR and Sam68. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7:10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lukong K.E., Richard S.. Sam68, the KH domain-containing superSTAR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003; 1653:73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ottesen E.W., Luo D., Seo J., Singh N.N., Singh R.N.. Human Survival Motor Neuron genes generate a vast repertoire of circular RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:2884–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao D.Y., Gish G., Braunschweig U., Li Y., Ni Z., Schmitges F.W., Zhong G., Liu K., Li W., Moffat J. et al.. SMN and symmetric arginine dimethylation of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain control termination. Nature. 2016; 529:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ottesen E.W., Seo J., Singh N.N., Singh R.N.. A multilayered control of the human survival motor neuron gene expression by alu elements. Front. Microbiol. 2017; 8:2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Seo J., Singh N.N., Ottesen E.W., Lee B.M., Singh R.N.. A novel human-specific splice isoform alters the critical C-terminus of Survival Motor Neuron protein. Sci. Rep. 2016; 6:30778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deininger P. Alu elements: know the SINEs. Genome Biol. 2011; 12:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rybak-Wolf A., Stottmeister C., Glazar P., Jens M., Pino N., Giusti S., Hanan M., Behm M., Bartok O., Ashwal-Fluss R. et al.. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, Conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol. Cell. 2015; 58:870–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumar L., Shamsuzzama, Haque R., Baghel T., Nazir A.. Circular RNAs: the emerging class of non-coding RNAs and Their potential role in human neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017; 54:7224–7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the finding of this study are available from corresponding authors upon reasonable request.