Abstract

Background

We compared the effects of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors on renal function in participants with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) classified by degree of albuminuria.

Methods

A retrospective review of the clinical records of Japanese participants with type 2 diabetes (age > 20 years; SGLT2 inhibitor treatment > 2 years; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) was conducted. Based on the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) or urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) at the start of SGLT2 inhibitor administration, participants were categorized into three groups: normoalbuminuria (A1; UACR < 30 mg/g Cr or UPCR < 0.15 g/g Cr), microalbuminuria (A2; UACR 30 to < 300 mg/g Cr or UPCR 0.15 to < 0.50 g/g Cr), and macroalbuminuria (A3; UACR ≥ 300 mg/g Cr or UPCR ≥ 0.50 g/g Cr). The study outcome was a comparison of the rates of change in renal function evaluated by eGFR at 2 years after starting SGLT2 inhibitor among the three groups.

Results

A total of 87 participants (40 females, 47 males) were categorized into three groups: A1 (n = 46), A2 (n = 25), and A3 (n = 16). eGFR was similarly decreased at 2 years before starting SGLT2 inhibitor in all three groups. However, the decline in eGFR was ameliorated at 2 years after starting SGLT2 inhibitor, and eGFR was rather increased in the A1 and A2 groups. Interestingly, the rate of change in eGFR at 2 years after starting SGLT2 inhibitor in the A1 group was significantly higher than that in the A3 group.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that more favorable effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on renal function were observed in participants with type 2 diabetes and CKD with normoalbuminuria compared with those with macroalbuminuria.

Trial registration UMIN-CTR: UMIN000035263. Registered 15 December 2018

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Diabetic kidney disease, Estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Background

Large randomized clinical trials have indicated that sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors can significantly ameliorate renal outcomes in participants with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular disease [1–6]. Furthermore, SGLT2 inhibitors were found to reduce the risk of renal disease progression by 45%, and show similar benefits for patients with and without established cardiovascular disease in a systematic review and meta-analysis [7]. Although a beneficial effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on the decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was observed in participants with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [8], it remains unclear whether the renoprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors vary depending on the degree of albuminuria. In the present study, we compared the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on renal function in participants with type 2 diabetes and CKD categorized into three groups: normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria, and macroalbuminuria.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The analyzed data were obtained from our previous retrospective observational study [9]. We conducted a retrospective review of the clinical records of Japanese participants with type 2 diabetes (age > 20 years; SGLT2 inhibitor treatment > 2 years; eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) in the outpatient center at Kurihara Clinic. Participants were excluded from the study if they had no clear data on eGFR or albuminuria. Participants with type 1 diabetes, and those with poor adherence or interruption of the medication were also excluded. An opt-out consent procedure was used. The study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Japan Clinicians Diabetes Association, and registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN; number UMIN000035263).

Study definitions and outcomes

Based on the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) or urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) at the start of SGLT2 inhibitor administration, participants were categorized into three groups: normoalbuminuria (A1; UACR < 30 mg/g Cr or UPCR < 0.15 g/g Cr), microalbuminuria (A2; UACR 30 to < 300 mg/g Cr or UPCR 0.15 to < 0.50 g/g Cr), and macroalbuminuria (A3; UACR ≥ 300 mg/g Cr or UPCR ≥ 0.50 g/g Cr) [10, 11]. The study outcome was a comparison of the rates of change in renal function evaluated by eGFR at 2 years after starting SGLT2 inhibitor (%∆eGFR + 2y) among the three groups. As previously described [9], %∆eGFR + 2y and %∆eGFR − 2y were calculated as follows: %∆eGFR + 2y = [(eGFR at 2 years after starting SGLT2 inhibitor) − (eGFR at start of SGLT2 inhibitor)]/(eGFR at start of SGLT2 inhibitor); %∆eGFR–2y = [(eGFR at start of SGLT2 inhibitor) − (eGFR at 2 years before starting SGLT2 inhibitor)]/(eGFR at 2 years before starting SGLT2 inhibitor).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median. Differences in baseline characteristics and changes among the three groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Bonferroni test or the Chi square test, as appropriate. Simple linear regression analyses were performed to test for associations between %∆eGFR + 2y and baseline HbA1c or change in HbA1c. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel Statistics 2012 for Windows (SSRI Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

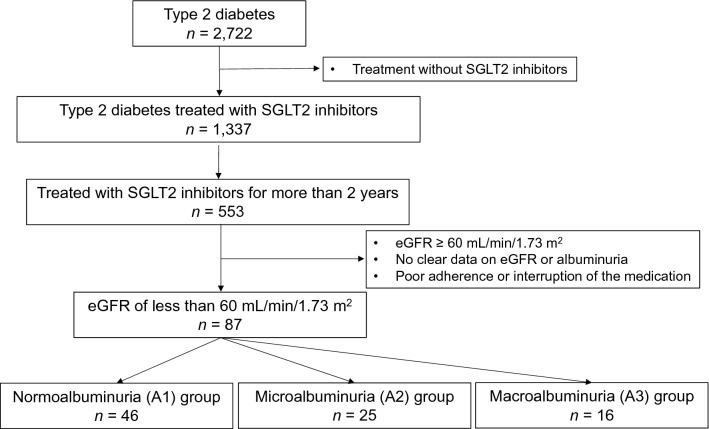

A total of 87 participants (40 females, 47 males) were divided into the three groups as follows (Fig. 1): A1 (n = 46), A2 (n = 25), and A3 (n = 16). The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences among the three groups in most of the parameters, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), duration of diabetes, eGFR, and blood pressure. However, HbA1c level in the A3 group was significantly higher than that in the A1 group.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the analysis in the study. eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, SGLT2 sodium–glucose cotransporter 2

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 87 participants

| A1 | A2 | A3 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 46 | 25 | 16 | |

| Sex (male/female) | 21/25 | 16/9 | 10/6 | 0.251 |

| Age (years) | 67.0 ± 8.9 | 66.8 ± 7.0 | 63.3 ± 8.9 | 0.287 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.8 ± 6.7 | 29.0 ± 4.2 | 28.3 ± 4.2 | 0.632 |

| Body weight (kg) | 75.5 ± 18.6 | 76.9 ± 13.4 | 74.0 ± 12.2 | 0.859 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 14.6 ± 6.7 | 15.8 ± 7.6 | 18.0 ± 8.8 | 0.284 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 1.0 * | 0.015 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 47.2 ± 8.7 | 48.5 ± 8.8 | 42.5 ± 9.6 | 0.105 |

| Category of GFR (G3a/G3b/G4) | 27/18/1 | 18/6/1 | 9/6/1 | 0.681 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 127.6 ± 8.9 | 130.6 ± 11.5 | 131.2 ± 10.8 | 0.323 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 74.3 ± 7.7 | 72.9 ± 10.6 | 73.8 ± 7.1 | 0.813 |

| ARB or ACE-I (%) | 82.6 | 96.0 | 100.0 | |

| SGLT2 inhibitor (%) | ||||

| Canagliflozin | 23.9 | 12.0 | 37.5 | |

| Dapagliflozin | 13.0 | 8.0 | 6.3 | |

| Empagliflozin | 8.7 | 4.0 | 12.5 | |

| Ipragliflozin | 4.3 | 20.0 | 18.8 | |

| Luseogliflozin | 6.5 | 20.0 | 6.3 | |

| Tofogliflozin | 43.5 | 36.0 | 18.8 | |

| Other oral hypoglycemic agents (%) | ||||

| Sulfonylurea | 50.0 | 52.0 | 62.5 | |

| Biguanide | 71.7 | 80.0 | 93.8 | |

| Thiazolidinedione | 2.2 | 8.0 | 14.3 | |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 15.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | |

| Glinide | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 50.0 | 76.0 | 62.5 | |

| Insulin (%) | 13.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD

ACE-I angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker, DPP-4 dipeptidyl peptidase-4, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, SGLT2 sodium–glucose cotransporter 2

*P < 0.05 vs. A1 group

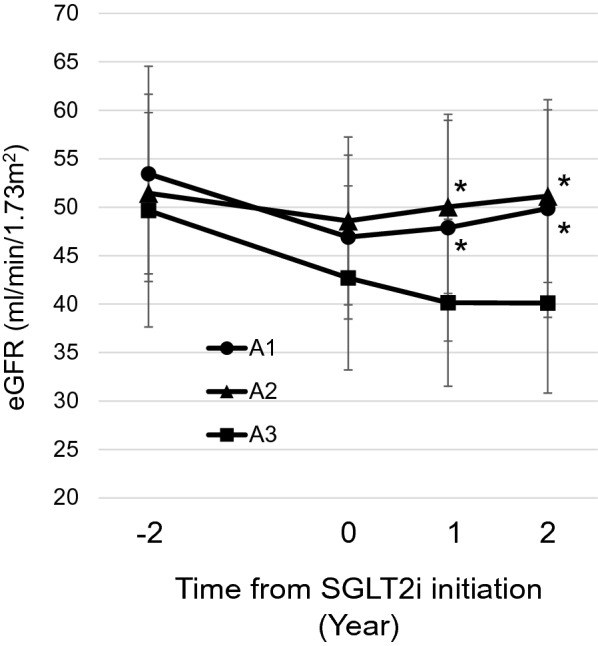

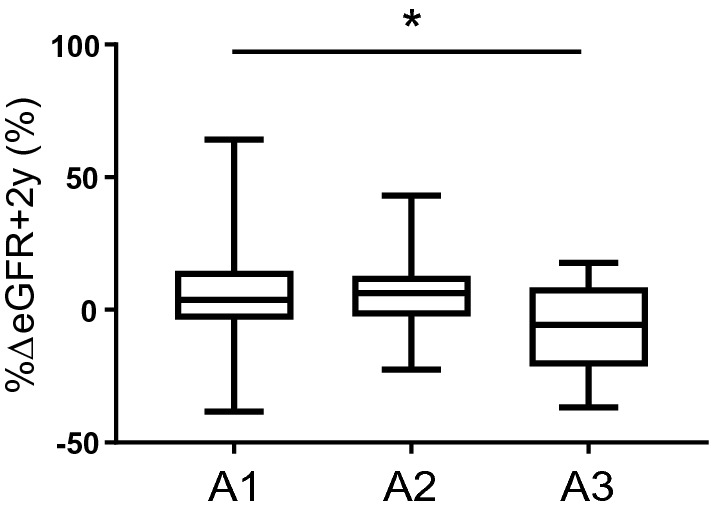

As shown in Fig. 2, eGFR was similarly decreased at 2 years before starting SGLT2 inhibitor in all three groups (%∆eGFR − 2y: − 10.8% ± 13.5% in A1 group, − 5.1% ± 12.6% in A2 group, − 12.8 ± 14.7% in A3 group; P = 0.135). However, the decline in eGFR was ameliorated at 2 years after starting SGLT2 inhibitor, and eGFR was rather increased in the A1 and A2 groups. Interestingly, %∆eGFR + 2y in the A1 group was significantly higher than that in the A3 group (Fig. 3). %∆eGFR + 2y was not associated with baseline HbA1c (correlation coefficient: 0.068, P = 0.532) or change in HbA1c (correlation coefficient: − 0.101, P = 0.353).

Fig. 2.

Serial changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 2 years before and after starting sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor in participants with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease in three groups: normoalbuminuria (A1; n = 46), microalbuminuria (A2; n = 25), and macroalbuminuria (A3; n = 16). *P < 0.05 vs. A3, one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Bonferroni test

Fig. 3.

Rates of change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 2 years after starting sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (%∆eGFR + 2y) in participants with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease in three groups: normoalbuminuria (A1; n = 46), microalbuminuria (A2; n = 25), and macroalbuminuria (A3; n = 16). *P < 0.05 between A1 and A3 group, one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Bonferroni test

Discussion

The present results indicated that %∆eGFR + 2y in the A1 group was significantly higher than that in the A3 group. Because baseline HbA1c in the A1 group was lower than that in the A3 group, we assumed that glucose tolerance could affect %∆eGFR + 2y. However, there was no association between %∆eGFR + 2y and baseline HbA1c or change in HbA1c at 2 years. These data suggest that glucose tolerance is not related to %∆eGFR + 2y. Recently, it was reported that the incidence of low eGFR with normoalbuminuria has been increasing in type 2 diabetes [10, 12, 13]. Pathological findings revealed that tubulointerstitial and vascular lesions tended to be more advanced in participants with type 2 diabetes and CKD with normoalbuminuria than those in participants with microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria [11, 14, 15]. Because the possible mechanisms for the renoprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors are assumed to include not only reduction in glomerular hyperfiltration as a result of tubuloglomerular feedback restoration, but also improvement of tubulointerstitial damage [16, 17], improved tubular cell injury may contribute to the greater beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in participants with type 2 diabetes and CKD with normoalbuminuria. Recent reports have shown a putative protective effect of SGLT2 inhibitors against tubular cell injury. In in vitro studies of proximal tubular cells, SGLT2 inhibitors suppressed the hyperglycemia-induced production of reactive oxygen species and angiotensinogen [18, 19]. In mice fed a high-fat diet, ipragliflozin improved proximal tubular cell integrity by reducing mitochondrial damage [20]. Furthermore, a cross-over clinical study showed that treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the urinary excretion of markers of tubular injury and inflammatory markers in participants with type 2 diabetes [17].

The main limitations of the present study are its retrospective design and relatively small sample. Other limitations are the relatively short follow-up duration and the study endpoint of changes in renal function evaluated by eGFR, rather than hard endpoints such as initiation of renal-replacement therapy or death from renal disease. Further studies are needed to verify our results in a prospective larger cohort for a longer observational period.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that more favorable effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on renal function were observed in participants with type 2 diabetes and CKD with normoalbuminuria than in participants with macroalbuminuria. These findings suggest that the renoprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in participants with CKD can vary depending on the degree of albuminuria.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants at Kurihara Clinic. We also thank Alison Sherwin, PhD, from Edanz Group (http://www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- SGLT2

sodium–glucose cotransporter 2

- UACR

urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio

- UPCR

urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio

Authors’ contributions

AN contributed in writing the manuscript. AN, HK and KY contributed to the data analysis. AN, HY, HK and YK contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. HK is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study did not supported by anywhere.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Japan Clinicians Diabetes Association, and registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN; number UMIN000035263).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AN. has obtained research support from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co. and Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. H.M. has received honoraria for lectures from Astellas Pharma Inc., Dainippon Pharma Co., Eli Lilly, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., MSD, Novartis Pharma, Novo Nordisk Pharma, Kowa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Sanofi, and has received research funding from Astellas Pharma Inc., Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon Pharma Co., Eli Lilly, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Novo Nordisk Pharma, Kowa Pharmaceutical Co., Abbott Japan Co., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Y.K. has received honoraria for lectures from Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co. Ltd., MSD, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Sanofi, Shionogi & Co. Ltd., Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. H.K. and K.Y.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:323–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherney DZI, Zinman B, Inzucchi SE, et al. Effects of empagliflozin on the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease: an exploratory analysis from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2017;5:610–621. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: results from the CANVAS program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2018;6:691–704. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Cahn A, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on development and progression of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 randomised trial. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2019;7:606–617. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2295–2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyoshi H, Kameda H, Yamashita K, et al. Protective effect of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in patients with rapid renal function decline, stage G3 or G4 chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. J Diab Invest. 2019;10:1510–1517. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kume S, Araki SI, Ugi S, et al. Secular changes in clinical manifestations of kidney disease among Japanese adults with type 2 diabetes from 1996 to 2014. J Diab Invest. 2019;10:1032–1040. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu M, Furuichi K, Toyama T, et al. Long-term outcomes of Japanese type 2 diabetic patients with biopsy-proven diabetic nephropathy. Diab Care. 2013;36:3655–3662. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, et al. Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among us adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA. 2016;316:602–610. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shikata K, Kodera R, Utsunomiya K, et al. Prevalence of albuminuria and renal dysfunction and related clinical factors in Japanese patients with diabetes: the Japan diabetes complication and its prevention prospective study (JDCP study 5) J Diab Invest. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jdi.13116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekinci EI, Jerums G, Skene A, et al. Renal structure in normoalbuminuric and albuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function. Diab Care. 2013;36:3620–3626. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu M, Furuichi K, Yokoyama H, et al. Kidney lesions in diabetic patients with normoalbuminuric renal insufficiency. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014;18:305–312. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0870-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alicic RZ, Neumiller JJ, Johnson EJ, et al. sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition and diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2019;68:248–257. doi: 10.2337/dbi18-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dekkers CCJ, Petrykiv S, Laverman GD, et al. Effects of the SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on glomerular and tubular injury markers. Diab Obes Metab. 2018;20:1988–1993. doi: 10.1111/dom.13301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishibashi Y, Matsui T, Yamagishi S. Tofogliflozin, a highly selective inhibitor of SGLT2 blocks proinflammatory and proapoptotic effects of glucose overload on proximal tubular cells partly by suppressing oxidative stress generation. Horm Metab Res. 2016;48:191–195. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satou R, Cypress MW, Woods TC, et al. Blockade of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 suppresses high glucose induced angiotensinogen augmentation in renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00402.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takagi S, Li J, Takagaki Y, et al. Ipragliflozin improves mitochondrial abnormalities in renal tubules induced by a high-fat diet. J Diab Invest. 2018;9:1025–1032. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.