Abstract

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), represents a subtype of breast cancer in which the estrogens receptor (ER) negative, the progesterone receptor (PR) negative and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative, are not expressed. Thusly, TNBC does not respond to hormonal therapies or to those targeting the HER2 protein receptors. To overcome this flawed issue, new alternative therapies based on the use of natural substances, as the (−) - epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCG), has been proposed. It is largely documented that EGCG, the principal constituent of green tea, has suppressive effects on different types of cancer, including breast cancer, through the regulation of different signaling pathways. Thus, is reasonable to assume that EGCG could be viewed as a therapeutic option for the prevention and the treatment of TNBC. Here, we summarizing these promising results with the scope of turn a light on the potential roles of EGCG in the treatment of TNBC patients.

Keywords: Triple-negative breast cancer, (−)-epigallocatechin 3-gallate, Anticancer activity, Apoptosis

Background

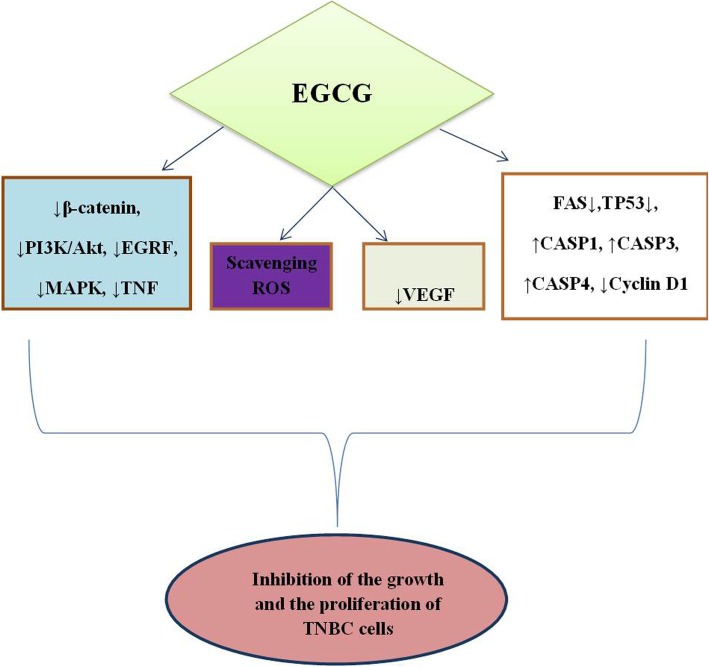

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), accounting for 15–20% of breast cancer with diagnosis, is an aggressive disorder with a poor prognosis frequently founded in African women with mutations in BCRA1 gene [1]. This tumor, classified as basal-like cancer on the basis of its morphology [2], does not express the estrogen receptor (ER), the progesterone receptor (PR), and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative (neu) markers [3]. Thus, TNBC fails to respond to therapies targeting the HER2 protein receptors or to conventional treatments. Regarding eziopathogenesis of breast cancer, a recent study highlighted a link between the bovine leukemia virus (BLV) and breast cancer, suggesting that the DNA of BLV in mammary tissue could be considered an important marker for breast cancer [4]. Moreover, Banerjee S et al., identified the microbial signatures associated with TNBC, by using a pan-pathogen array technology in order to provide the new diagnostic potential for this type of cancer viruses [5]. Unfortunately, there are no successful therapies for TNBC, thus new elective treatments engineered on the use of natural substances, have been developed in order to change the conventional schedule of therapies. Particularly, several studies identified the polyphenols as adjuvants to chemotherapeutic drugs in TNBC cells [6, 7]. Many reports highlighted the role of EGCG against the progression of different types of cancer, including breast cancer, thought the modulation of different molecular pathways [8–15]. Specifically, it has been showed that EGCG inhibited breast cancer cell growth by enhancing the chemotherapeutic-induced cellular apoptosis [16], and by modulating different molecular signaling pathways as the nuclear factor-κB (NF- κβ), the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the phosphatidylinositol-3 (PI3) kinase [17–20]. Moreover, it has been proved that EGCG retarded the growth of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells, by inactivating the β-catenin signaling pathway (Fig. 1) [21]. Overall, these findings demonstrate that EGCG could be considered as a new agent for the treatment of patients suffering from TNBC.

Fig. 1.

Molecular mechanism underlying the antitumor effect of EGCG in Triple Negative breast cancer cells. EGCG: epigallocatechin-3-gallate; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; EGRF: epidermal growth factor receptor; MARK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; ROS: reactive oxygen species; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; FAS: fas cell surface death receptor; CASP1: caspase 1; CASP3: caspase 23; CASP4: caspase 4; TP53: tumor protein p-53; TNBC: triple negative

An overview of the role of EGCG in TNBC cells growth: findings from in vitro studies

Accumulated in vitro studies highlighted the role of EGCG in the inhibition of TNBC cells growth, through the regulation of various molecular pathways (Table 1). The first study on this issue was conducted by Braicu et al. on Hs578T cells. Authors showed that the galloylated flavan-3-ols, and particularly EGCG, inhibited the cell proliferation by inducing the apoptosis, due to their ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS). Moreover, flavan-3-ols showed antioxidants or pro-oxidants properties depending on the dose and the exposure time of the cell culture [22]. Particularly, it was demonstrated that EGCG reduced or increased the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) respect to controls and to others galloylated flavan-3-oils, at doses of 10 and 100 μM. In a subsequent investigation, the same authors demonstrated that EGCG (20 μM) inhibited the proliferation of Hs578T cells after 48 and 72 h of treatments, mainly by activating the apoptotic processes. By using the PCR-array technology, it has been shown that EGCG altered the expression of many genes involved in different molecular pathways (Table 1). EGCG downregulated the expression of several anti-apoptotic genes (insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor: IGF1R; induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein: MCL1) while increased the expression of other genes (B-cell lymphoma 2: Bcl2; associated athanogene 3: BAG3; receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2: RIPK2; X-Linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis: XIAP) probably due to resistance to cancer treatment [23]. Later on, a suppressive role of EGCG on TNBC cell migration was associated with VEGF expression inhibition [24], suggesting that EGCG could be used to arrest breast tumor invasion. In a fascinating study, Braicu et al. proposed that the combination of p53 siRNA and EGCG, through the activation of apoptosis and autophagy, potentiated the antitumor effects of EGCG in Hs578T cells [25].

Table 1.

In vitro findings on the role of EGCG in TNBC cells

| Cell lines | Dose of EGCG | Molecular targets | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hs578T | 10, 100 μM | ROS ↓ (at 10 μM) ROS ↑ (at 100 μM) | [22] |

| Hs578T | 20 μM |

CASP1, CASP3, CASP4, PYCARD, BAG3, RIPK2, XIAP↑ IGF1R, MCL1, TNF↓; |

[23] |

| Hs578T | 10 μM | VEGF↓ | [24] |

| Hs578T | 10 μM plus 40 nmol p53-siRNA | PYCARD, BAD, BAG3, CD40LG, CD40, CD27, TNFRSF1A, TNFSF8, CARD6, LTBR, BAK1↑; IGF1R, MCL1, TNFRSF25, BRAF, FAS, TP53↓; | [25] |

| MDA-MB-231 |

25, 50, 75, 100, 200 μM. Pretreatment with 25 μM LY294002 or 5 μM wortmannin + plus 200 μM EGCG added after 24 h |

β-catenin, p-AKT, cyclin D1↓ | [21] |

| MDA-MB231 | IC50 (μM) of Epigallocatechin 3- Gallate Synthetic Analogues: G28, G37, G56, M1, M2, G75 (−)- | FASN↓ PARP ↑ | [26] |

| MCF-7, MDA-MB- 231, MDA-MD-157, HCC1806 | 3 μM m SAHA, 5 μM EGCG |

miR-221/222, p27, ERα, PTEN, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, |

[27] |

Abbreviations: EGCG epigallocatechin-3-gallate, ROS reactive oxygen species, CASP1 caspase 1, CASP3 caspase 3, CASP4 caspase 4, PYCARD apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a card, IGF1R insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, MCL1 induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein, TNF tumor necrosis factor, BAG3 bcl2 associated athanogene 3, RIPK2 receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2, XIAP X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, BAD BCL2 associated agonist of cell death, TNFRSF1A tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A, TNFSF8 tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily, member 8, CARD6 caspase recruitment domain family member 6, LTBR lymphotoxin beta receptor, BAK1 BCL2 antagonist/killer 1, TNFRSF25 tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 25, BRAF b-raf serine/threonine-protein, FAS fas cell surface death receptor, TP53 tumor protein p-53, p-AKT phospho-AKT, PARP poly(ADP- ribose) polymerase, SAHA suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, miR-221/222 microRNA 221/222, ERα estrogen receptor alpha, PTEN phosphatase and tensin homolog

A different molecular mechanism underlying the inhibitory role of EGCG on TNBC cell growth was reported by Hong et al. [21]. Specifically, the authors firstly evaluated a presumable association between β-catenin expression and clinical conditions of female patients with invasive ductal carcinoma, and then they examined the effect of EGCG on β- catenin expression in triple-negative breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231. Results of western blot analysis conducted in breast cancer and normal tissue of female enrolled in this study, revealed that the expression levels of β-catenin were higher in breast cancer tissue than in normal tissue. Accordingly, EGCG decreased the cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner, by downregulating the expression of β-catenin, cyclin D1, and phosphorylated Akt (p-AKT). Moreover, pre-treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with peptidase inhibitor 3 (PI3) kinase inhibitors, (LY294002 or wortmannin) potentiated the suppressive effect of EGCG, added after 24 h, on β-catenin expression. Taken together, these data suggest that EGCG is able to inhibit the growth of MDA-MB-231 by interfering with the β-catenin signaling pathway.

Encouraging results on the effects of (−)-Epigallocatechin 3-gallate synthetic analogs on TNBC cells were depicted by Crous-Masò. In this study were generated three diesters (G28, G37, G56), two G28 derivatives and two monoesters M1 and M2. Then, these compounds were tested in vitro on MDA-MB-231 cells. Specifically were evaluated their cytotoxic effects, their inhibition of lipogenic enzyme fatty acid synthase (FANS) and their apoptotic activities. Data emerged from these experiments, showed that all compounds blocked the activity of FASN. Particularly, the monoesters inhibited the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells more than the diesters, and only the monoesters induced the apoptosis detected by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage. Altogether, these results suggest that these polyphenolic compounds, particularly the monoesters, due to their inhibitory role on FASN, could represent a new strategy for TNBC treatment [26].

A recent study evaluated the effects of Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor and EGCG on the growth and the proliferation of TNBC cells [27]. Results showed that these substances reduced the expression of miR-221/222 and N-cadherin and increased the expression of p27, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and E-cadherin. These findings, likewise associated with reduced activity of DNA methyltransferase (DNMTs), indicate that SAHA and EGCG reduced the growth and the proliferation of TNBC cancer cells, probably by acting on epigenetic mechanisms.

The antitumor effects of EGCG in TNBC mouse models: a current state of knowledge

The antitumor effects of EGCG on TNBC have been also confirmed by in vivo experiments, as summarized in Table 2. A first study was conducted by Thangapazham al [20]. Authors showed that EGCG (administered at the dose of 1 mg/animal in 100 μl of distilled water for 10 weeks), and GTP (green tea polyphenols, 1% for 10 weeks) decreased the proliferation and increased the apoptosis of tumors of TNBC mouse model. Importantly, these results were firstly proved in vitro. Specifically, GTP (10–150 μg/ml) and EGCG (1–200 μg) inhibited cell growth in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, an arrest of the cell cycle at G1 phase, confirmed by a downregulated expression of Cyclin D, Cyclin E, Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK 4), Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK 1) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), was observed in cells treated with GTP and EGCG. An interesting study conducted on the same TNBC mouse model tested the effect of a novel EGCG prodrug on tumor growth [28]. Specifically, this compound, named Pro-EGCG (1), was engineered to enhance the stability of EGCG by introducing the peracetate-protecting groups to the reactive hydroxyls of EGCG. By using this approach, the authors showed that in MDA-MB-231 cells, Pro-EGCG (1) was converted to its parent compound EGCG that was then accumulated. Thus, the cells treated with Pro-EGCG (1) (50 μmol/L), showed increased levels of proteasome inhibition, growth suppression and apoptosis compared to cells treated with EGCG. These data were also confirmed in vivo by injecting the MDA-MB-231 cells in nude mice, followed by treatment with Pro-EGCG (1) (50 mg/kg) or EGCG (50 mg/kg) for 31 days. Data emerged from this experiment showed that Pro-EGCG (1) inhibited breast tumor growth and proteasome, while induced the apoptosis compared to EGCG, suggesting its use for TNBC prevention and treatment. Similar reports were showed by Yang et al. [29] with the utilization of the prodrugs of EGCG’s flour-substituted analogs: Pro-F-EGCG2 (Pro-F2) or Pro-F-EGCG4 (Pro-F4) and Pro-EGCG 1. These compounds (50 mg/kg administered by s.c. injection daily for 31 days), equally, inhibited the growth and the proteasome and enhanced the apoptosis in breast tumors of mice.

Table 2.

In vivo experiments on the antitumor effects of EGCG on TNBC: an update

| Animal models | Drug | Dose | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft mouse model (MDA-MB-231 cells injected into the dorsal subcutaneous tissue of mice) | EGCG GTP |

1 mg/0.1 ml/mouse of EGCG in drinking water for 10 weeks; 0,1% GTP for 10 weeks; |

EGCG and GTP decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of tumors of TNBC- bearing mice. | [20] |

| Xenograft mouse model (MDA-MB-231 cells injected into the dorsal subcutaneous tissue of mice) |

EGCG Pro- EGCG (1) |

50 mg/kg Pro- EGCG(1) for 31 days; 50 mg/kg EGCG(1) for 31 days; |

Pro-EGCG (1) targeted the tumor cellular proteasome and inhibited the growth of tumors of TNBC-bearing mice. | [28] |

| Xenograft mouse model (MDA-MB-231 cells injected into the dorsal subcutaneous tissue of mice) injected into the right axilla of mice) |

Pro-F- EGCG2 (Pro-F2) Pro-F- EGCG4 (Pro-F4) Pro- EGCG (1) |

50 mg/kg by s.c. injection daily for 31 days, Pro-F2; 50 mg/kg by s.c. injection daily for 31 days, Pro-F4; 50 mg/kg by s.c. injection daily for 31 days, Pro-EGCG (1) |

Pro-F2 and Pro-F4 induced proteasome inhibition and apoptosis induction and similar to Pro-EGCG (1), inhibited the growth of tumors of TNBC-bearing mice. | [29] |

Abbreviations: EGCG epigallocatechin-3-gallate, GTP green tea polyphenols, TNBC triple negative breast cancer, Pro-EGCG(1) peracetate-protecting groups to the reactive hydroxyls of (−)-EGCG, Pro-F2 prodrugs of fluoro-substituted EGCG analog-42, Pro-F4 prodrugs of fluoro- substituted EGCG analog-4, s.c. subcutaneously

Limitations of the use of EGCG into clinical practice and future perspectives

The aforementioned results strongly indicate that EGCG can restrain the growth and the proliferation of TNBC by acting on different molecular pathways. Thus, EGCG might be viewed as an alternative treatment for TNBC patients. Notwithstanding these encouraging pre-clinical outcomes, no clinical trials have been conducted, until now, on TNBC patients. Lamentably, the data obtained from in vivo and human epidemiological studies on other types of breast cancer, are inconsistent and in some cases contradictory [30]. Moreover, EGCG possesses poor bioavailability and poor stability and these highlights change between in vitro and in vivo conditions [31, 32], thus representing a limitation for EGCG’s use in human populations. To conquer this issue, new strategies based on the use of nanoparticles (NPs) or micro-particles in which EGCG is encapsulated, have been effectively built to improve EGCG’s stability and bioavailability [33–39].

Further investigations will be important not only to improve EGCG oral bioavailability, yet additionally to stabilize this compound in the stomach related tract. Overall, EGCG could be firmly viewed as a powerful inhibitor of TNBC progression.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Alessandra Trocino and Mrs. Maria Cristina Romano from the National Cancer Institute of Naples for providing excellent bibliographic service and assistance.

Abbreviations

- BAD

BCL2 associated agonist of cell death

- BAG3

bcl2 associated athanogene 3

- BAK1

BCL2 antagonist/killer 1

- BRAF

b-raf serine/threonine-protein

- CARD6

Caspase recruitment domain family member 6

- CASP1

Caspase 1

- CASP3

Caspase 3

- CASP4

Caspase 4

- EGCG

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- ERα

Estrogen receptor alpha

- FAS

Fas cell surface death receptor

- GTP

Green tea polyphenols

- IGF1R

Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- LTBR

Lymphotoxin beta receptor

- MCL1

Induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein

- miR-221/222

MicroRNA 221/222

- p-AKT

Phospho-AKT

- PARP

Poly(ADP- ribose) polymerase

- Pro-EGCG(1)

Peracetate-protecting groups to the reactive hydroxyls of (−)-EGCG

- Pro-F2

Prodrugs of fluoro-substituted EGCG analog-42

- Pro-F4

Prodrugs of fluoro- substituted EGCG analog-4

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- PYCARD

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a card

- RIPK2

Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SAHA

Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TNFRSF1A

Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A

- TNFRSF25

Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 25

- TNFSF8

Tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily, member 8

- TP53

Tumor protein p-53

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

Authors’ contributions

The present review was mainly written by SB and MC. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alluri P, Newman L. Basal-like and triple negative breast cancers: searching for positives among many negatives. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23:567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:674–690. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buehring GC, et al. Bovine leukemia virus DNA in human breast tissue. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:772–782. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.131298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee S, Wei Z, Tan F, Peck KN, Shih N, Feldman M, Rebbeck TR, Alwine JC, Robertson ES. Distinct microbiological signatures associated with triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;15:15162. doi: 10.1038/srep15162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisholm K, Bray BJ, Rosengren RJ. Tamoxifen and epigallocatechin gallate are synergistically cytotoxic to MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2004;15:889–897. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sak K. Chemotherapy and dietary phytochemical agents. Chemother Res Pract. 2012;2012:282570. doi: 10.1155/2012/282570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bimonte S, Albino V, Piccirillo M, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate in the prevention and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: experimental findings and translational perspectives. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:611–621. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S180079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bimonte S, Leongito M, Barbieri A, et al. Inhibitory effect of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and bleomycin on human pancreatic cancer MiaPaca-2 cell growth. Infect Agent Cancer. 2015;10:22. doi: 10.1186/s13027-015-0016-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modernelli A, Naponelli V, Giovanna Troglio M, et al. EGCG antagonizes Bortezomib cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cells by an autophagic mechanism. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15270. doi: 10.1038/srep15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avtanski D, Poretsky L. Phyto-polyphenols as potential inhibitors of breast cancer metastasis. Mol Med. 2018;24(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s10020-018-0032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada S, Tsukamoto S, Huang Y, Makio A, Kumazoe M, Yamashita S, Tachibana H. Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate up-regulates microrna-let-7b expression by activating 67-kda laminin receptor signaling in melanoma cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19225. doi: 10.1038/srep19225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L, Zhang E, Shi J, Li X, Zhou K, Zhang, Le AD, Tang X. (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits human papillomavirus (hpv)-16 oncoprotein-induced angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting hif-1alpha. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:713–725. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Nam HJ, Kang HJ, Kwon HW, Lim YC. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates head and neck cancer stem cell traits through suppression of notch pathway. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3210–3218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adachi S, Nagao T, Ingolfsson HI, Maxfield FR, Andersen OS, Kopelovich L, Weinstein IB. The inhibitory effect of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate on activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor is associated with altered lipid order in ht29 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6493–6501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy AM, Baliga MS, Katiyar SK. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces apoptosis in estrogen receptor-negative human breast carcinoma cells via modulation in protein expression of p53 and Bax and caspase-3 activation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu YC, Liou YM. The anticancer effects of (−)-Epigalocathine-3-gallate on the signaling pathways associated with membrane receptors in MCF-7 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2721–2730. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan N, Afaq F, Saleem M, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H. Targeting multiple signaling pathways by green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2500–2505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuart EC, Scandlyn MJ, Rosengren RJ. Role of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in the treatment of breast and prostate cancer. Life Sci. 2006;79:2329–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thangapazham RL, Singh AK, Sharma A, Warren J, Gaddipati JP, Maheshwari RK. Green tea polyphenols and its constituent epigallocatechin gallate inhibits proliferation of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2007;245:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong OY, Noh EM, Jang HY, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits the growth of MDA- MB-231 breast cancer cells via inactivation of the β-catenin signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(1):441–446. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braicu C, Pilecki V, Balacescu O, Irimie A, Neagoe IB. The relationships between biological activities and structure of flavan-3-ols. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(12):9342–9353. doi: 10.3390/ijms12129342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braicu Cornelia, Gherman Claudia. Epigallocatechin gallate induce cell death and apoptosis in triple negative breast cancer cells Hs578T. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2012;21(3):250–256. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2012.740673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braicu C, Gherman CD, Irimie A, Berindan-Neagoe I. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) inhibits cell proliferation and migratory behaviour of triple negative breast cancer cells. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013;13(1):632–637. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2013.6882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braicu C, Pileczki V, Pop L, et al. Dual targeted therapy with p53 siRNA and Epigallocatechingallate in a triple negative breast cancer cell model. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0120936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crous-Masó J, Palomeras S, Relat J, et al. (−)-epigallocatechin 3-gallate synthetic analogues inhibit fatty acid synthase and show anticancer activity in triple negative breast cancer. Molecules. 2018;23(5):1160. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis KA, Jordan HR, Tollefsbol TO Effects of SAHA and EGCG on growth potentiation of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Cancers (Basel) 2018;11(1):23. doi: 10.3390/cancers11010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landis-Piwowar KR, Huo C, Chen D, Milacic V, Shi G, Chan TH, Dou QP. A novel prodrug of the green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate as a potential anticancer agent. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4303–4310. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H, Sun DK, Chen D, et al. Antitumor activity of novel fluoro-substituted (−)- epigallocatechin-3-gallate analogs. Cancer Lett. 2009;292(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiang LP, Wang A, Ye JH, et al. Suppressive effects of tea catechins on breast cancer. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):458. doi: 10.3390/nu8080458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weng Z, Greenhaw J, Salminen WF, Shi Q. Mechanisms for epigallocatechin gallate induced inhibition of drug metabolizing enzymes in rat liver microsomes. Toxicol Lett. 2012;214:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenz M, Paul F, Moobed M, Baumann G, Zimmermann BF, Stangl K, Stangl V. The activity of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is not impaired by high doses of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suganuma M, Okabe S, Sueoka N, Sueoka E, Matsuyama S, Imai K, Nakachi K, Fujiki H. Green tea and cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res. 1999;428:339–344. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(99)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forester SC, Lambert JD. The catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor, tolcapone, increases the bioavailability of unmethylated (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in mice. J Funct Foods. 2015;17:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krupkova O, Ferguson SJ, Wuertz-Kozak K. Stability of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate and its activity in liquid formulations and delivery systems. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dube A, Nicolazzo JA, Larson I. Chitosan nanoparticles enhance the intestinal absorption of the green tea catechins (+)-catechin and (−)-epigallocatechingallate. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;41:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yadav R, Kumar D, Kumari A, Yadav SK. Encapsulation of catechin and epicatechin on BSA NPs improved their stability and antioxidant potential. EXCLI J. 2014;13:331–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang J, Cao L, Zhang L, Wan X. Preparation, characterization, and in vitro antitumor activity of folate conjugated chitosan coated EGCG nanoparticles. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2014;23:569–575. doi: 10.1007/s10068-014-0078-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fangueiro JF, Calpena AC, Clares B, Andreani T, Egea MA, Veiga FJ, Garcia ML, Silva AM, Souto EB. Biopharmaceutical evaluation of epigallocatechin gallate-loaded cationic lipid nanoparticles (EGCG-LNs): in vivo, in vitro and ex vivo studies. Int J Pharm. 2016;502:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.