Abstract

Background

Real-world evidence of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goal attainment rates for Asian patients is deficient. The objective of this study was to assess the status of dyslipidemia management, especially in high-risk patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) including stroke and acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of 514,866 subjects from the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort database in Korea. Participants were followed up from 2002 to 2015. Subjects with a high-risk of CVD prior to LDL-C measurement and subjects who were newly-diagnosed for high-risk of CVD following LDL-C measurement were defined as known high-risk patients (n = 224,837) and newly defined high-risk patients (n = 127,559), respectively. Data were analyzed by disease status: stroke, ACS, coronary heart disease (CHD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), diabetes mellitus (DM) and atherosclerotic artery disease (AAD).

Results

Overall, less than 50% of patients in each disease category achieved LDL-C goals (LDL-C < 70 mg/dL in patients with stroke, ACS, CHD and PAD; and LDL-C < 100 mg/dL in patients with DM and AAD). Statin use was observed in relatively low proportions of subjects (21.5% [known high-risk], 34.4% [newly defined high-risk]). LDL-C goal attainment from 2009 to 2015 steadily increased but the goal-achiever proportion of newly defined high-risk patients with ACS remained reasonably constant (38.7% in 2009; 38.1% in 2015).

Conclusions

LDL-C goal attainment rates in high-risk patients with CVD and DM in Korea demonstrate unmet medical needs. Proactive management is necessary to bridge the gap between the recommendations of clinical guidelines and actual clinical practice.

Keywords: Dyslipidaemia, Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, Stroke, Acute coronary syndrome, Cardiovascular disease, Diabetes mellitus, Statin

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally, with 17.9 million estimated deaths from CVD in 2016, representing 31% of all global deaths. Myocardial infarction and stroke account for 85% of CVD deaths [1]. Dyslipidemia is a major risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke [2–5], and includes elevated total cholesterol, triglycerides, or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, or low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels. The global disease burden of CVD increased by 12.5% [6], and this trend is attributed by Asians with fast growing of aged population [7]. However, evidence is limited for dyslipidemia management for high-risk CVD patients among Asians. Recent data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) reported that, in 2016, 19.9% of adults aged ≥30 years had hypercholesteremia and 40.5% had dyslipidemia [8]. The prevalence of dyslipidemia in Korea has increased in an age-dependent manner and is more evident in women aged ≥50 years [8–11]. The level of disease awareness was as low as 32.1% in men and 32.6% in women (aged 30–49 years) [11]. In one recent study in Korea, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was higher than that of hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM), but dyslipidemia awareness and treatment rates were still lower [12].

LDL-C remains the primary target of cholesterol-lowering therapy for the primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events including CHD, stroke, and peripheral artery disease (PAD). The cardiovascular risk level of individuals determines LDL-C treatment goals [2–4, 13–15]. Some differences in cholesterol-lowering guidelines have been described and these may, at least in part, be attributable to whether the guidelines are solely evidence-based or based on a combination of evidence and expert opinion [16, 17]. On the other hand, management of dyslipidemia was revolutionized since statins were discovered. Statins are known to substantially reduce LDL-C levels and CVD mortality [18, 19]. Previous studies have shown that further reductions in LDL-C levels by more intensive statin therapy according to the risk of CVD have further benefits [20, 21].

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines [3] emphasized > 50% LDL-C reductions from baseline in high-risk patients. European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) guidelines in 2016 focused on < 70 mg/dL LDL-C reductions in high-risk patients [15]. Recently revised 2018 ACC/AHA guidelines emphasize using an LDL-C threshold of 70 mg/dL for considering the addition of non-statins to statin therapy in very high-risk patients, including a history of multiple major ASCVD events or one major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions [22]. This means that, in addition to percent LDL-C reductions from baseline, target LDL-C levels are also critical values as LDL-C treatment goals for dyslipidemia management. The latest Korean national guidelines were formulated from the Committee of Clinical Practice of the Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis for the Management of Dyslipidemia in 2018 [23]. It was generally based on the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel (NECP-ATP) [2] for the risk stratification and LDL-C treatment goal. However, > 50% LDL-C reduction was recommended according to ACC/AHA guidelines in case of ACS patients in addition to the LDL-C target < 70 mg/dL and intensity of statin also was recommend in accordance with the ACC/AHA guidelines [3]. The target of the recent American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guideline [4] for lowering LDL-C to less than 55 for extreme high risk was not included in the recommendations yet as consensus from domestic experts will be required.

Evidence of LDL-C goal attainment rates for Korean patients compared with other recently updated guidelines is currently lacking, particularly in high-risk patients. Therefore, it is needed to evaluate the status of dyslipidemia management in Korea in general, as well as specifically addressing the status of high-risk patients with stroke, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), CHD, PAD, DM and atherosclerotic artery disease (AAD). This study used absolute values for LDL-C level < 70 mg/dL in patients with very-high risk disease (stroke, ACS, CHD and PAD) and < 100 mg/dL LDL-C in high-risk patients (DM and AAD); and > 50% reduction using repeated measured LDL-C levels, as LDL-C treatment goals. Also, this study aimed to describe the time trends of LDL-C goal attainment rate in recent years using extensive national data. To identify the most appropriate populations to target with preventative therapies, subgroup analyses were conducted.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective cohort study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS), details of which have been described elsewhere [24]. The NHIS has provided a general national health screening program since 1995, and a health screening program for transitional ages, aimed at individuals aged 40 and 66 years, since 2007. The general health screening program is applied at least once every 2 years for the entire population of Korean adults aged ≥40 years; the participation rate was 74.8% in 2014. NHIS-HEALS incorporates information from these health screening programs [25].

The NHIS-HEALS database comprised 514,866 subjects (aged 40–79 years, 54.2% males) at baseline (2002–2003) who were randomly selected by simple random sampling using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and represented 10% of all national health screening participants (N = 5,148,695) in 2002 and 2003. Participants were followed up from 2002 to 2015 and data constructed in 2015. Variables included social and economic qualifications, medical check-up results, healthcare usage and survival status linked to national death certificates [24]. The healthcare usage database included information on records of inpatient and outpatient usage (diagnosis, procedures, and prescriptions). Diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) [26].

Risk stratification

Korean national guidelines [23] based on the risk stratification of NCEP-ATP III, categorized risk groups to very high-risk, high-risk, moderate-risk and low-risk and recommended LDL-C treatment goals dependent on risk assessment: very high-risk < 70 mg/dL, high-risk < 100 mg/dL, moderate-risk < 130 mg/dL, and low-risk < 160 mg/dL. Very high-risk consisted of ACS, stroke and TIA, and PAD; high-risk consisted of carotid artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and DM. According to guidelines, PAD and other AAD (including carotid artery disease and abdominal aortic aneurysm) were separated to adjust different LDL-C target goal. ICD-10 codes and related procedures for risk stratification were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of high-risk disease by ICD-10 codes and procedure code

| Disease | Diagnosis or procedure code |

|---|---|

| Stroke | Diagnosis: I63a, I64a, I69.3b, G45, G46 |

| ACS | Diagnosis: I21a, I22a, I23 |

| Procedure: | |

| Coronary artery bypass graft: OA640–2, OA647–9, O1640–2, O1647–9 | |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention: M6561–7, M6571–2 | |

| Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: M6551–4 | |

| CHD | Diagnosis: I20.0, I20.9, I24.0, I25.1, I25.2b, I25.5, I25.6 |

| PAD | Diagnosis: I70.2, I73.1, I73.8, I73.9 |

| DM | Diagnosis: E10, E11, E12, E13, E14 |

| AAD | Diagnosis: I65.2, I71.3, I71.4, I71.5, I71.6 |

AAD atherosclerotic artery disease, ACS acute coronary syndrome, CHD coronary heart disease, DM diabetes mellitus, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases (10th revision), PAD peripheral artery disease

aIncluded only in the case of hospitalization; bIncluded for Known high risk

Eligibility criteria

From the NHIS-HEALS database, patients with LDL-C measurements during 2007–2013 were included. Although data on participants’ total cholesterol levels are available from 2002, data for triglyceride, HDL-C and LDL-C levels are available for the health screening program for transitional ages from 2007, and for general national health screening programs from 2009. Patients with LDL-C measurement < 10 mg/dL during 2007–2013 were excluded. Subjects with a high-risk of CVD including stroke, ACS, CHD, PAD, DM and AAD were identified using ICD-10 codes and related procedures (Table 1) and classified into two groups: 1) known high-risk patients, 2) newly defined high-risk patients (Fig. 1).

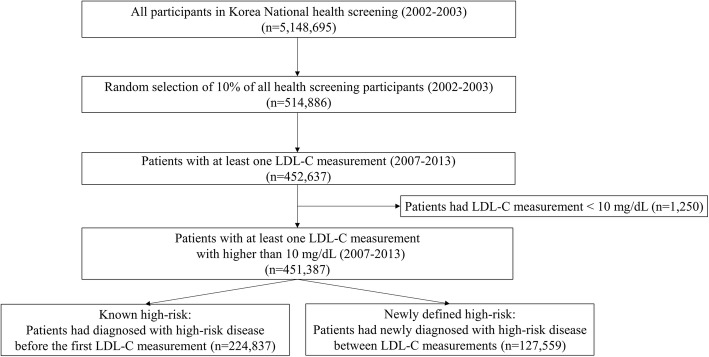

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection of high-risk category subjects

Subjects previously identified as having a high-risk for CVD, prior to measurement of LDL-C levels, were categorized as “known high-risk patients.” The index date is the first LDL-C testing date during the study period. Definition of high-risk status was required to be made in the previous year including the index date. Subjects categorized as “newly defined high-risk” were identified according to the following criteria: 1) patients with more than two LDL-C measurements, and 2) patients who were newly diagnosed or underwent procedures for high-risk CVD between two LDL-C measurements. As LDL-C levels were available from 2007, patients with new cases of each disease could be defined as having at least 5 years of disease-free periods. For subjects with newly defined high-risk disease, the earliest date of visit regarding high-risk disease was defined as the index date. Here is an example of the group definition. If a subject had five LDL-C measurements during the follow up period and there was a first diagnosis of DM prior to the first LDL-C measurement, he or she was defined as a known high-risk patient for DM; on the other hand, there was a first ACS diagnosis between the third and fourth LDL-C measurements, he or she was defined as a newly diagnosed high-risk patient for ACS.

Outcome variables: LDL-C goal attainment

Target LDL-C levels were defined by the 2018 Korean guidelines [23]. For patients with stroke, ACS, CHD or PAD, defined as the very high-risk group, the target level was < 70 mg/dL. For patients with DM or AAD, defined as high-risk group, the target level was < 100 mg/dL. When patients with DM or AAD had other concurrent high-risk diseases—stroke, ACS, CHD or PAD—these patients were stratified into the subgroups “DM with high-risk of CVD” and “AAD with high-risk of CVD” for outcome analysis, because their target level was < 70 mg/dL as very high-risk group. To determine LDL-C target achievement, LDL-C levels at the index date and LDL-C levels after the index date were used for known high-risk patients and newly defined high-risk patients, respectively.

LDL-C goal attainment by reduction rates were defined by 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines: > 50% reduction in baseline LDL-C for high-intensity statin and 30 to < 50% for moderate-intensity statin; guidelines recommend high-intensity statin therapy in patients with ASCVD or those with DM aged > 45 years [3]. In the present study, the two LDL-C levels just before and after the index date of newly defined high-risk patients were used to calculate changes in LDL-C levels. On average, the interval for the two LDL-C tests was approximately 1 year, due to government policy for providing the health screening program.

Assessment of statin use

Statins included atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin and simvastatin. Statin therapy intensity was classified as high-intensity (atorvastatin 40–80 mg, rosuvastatin 20 mg), moderate-intensity (atorvastatin 10–20 mg, fluvastatin 40–80 mg, lovastatin 40 mg, pitavastatin 2–4 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, rosuvastatin 5–10 mg, simvastatin 20–40 mg), and low-intensity (fluvastatin 20–40 mg, lovastatin 20 mg, pitavastatin 1 mg, pravastatin 5–20 mg, simvastatin 5–10 mg), according to generic name and dose.

Statin exposure was assessed on or within 30 days before the index date using the prescription date and duration in known high-risk patients. For newly defined high-risk patients, whether exposure to statin took place from 30 days before to 90 days after the index date, using prescription dates and duration was assessed. Subjects were classified by their statin use history, as existing users if receiving statins at the time of the index date or within 6 months before the index date, or new users if there was no record of statin use for 6 months prior to the index date.

Data analysis

General characteristics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, smoking, presence of diabetes, presence of hypertension, systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements, fasting blood glucose levels, total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-C and LDL-C, are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as frequency and proportion for categorical variables.

The proportion of patients attaining target LDL-C levels was calculated by dividing the number of patients with LDL-C level less than target level by the total number of patients. The proportion of patients with > 50% reduction of LDL-C levels was calculated by dividing the number of patients with > 50% reduction of LDL-C from the previous LDL-C level by the total number of patients. All LDL-C measurements from the index date were included to identify annual trend. Data were analyzed by disease status: stroke, ACS, CHD, PAD, DM and AAD. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

The NHIS-HEALS database (n = 514,866) included high-risk patients either before LDL-C measurement (known high-risk; n = 224,837) or following LDL-C measurement (newly defined high-risk; n = 127,559) (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of subjects stratified by cardiovascular risk category (known or newly defined high-risk), and by disease, are shown in Tables 2 and 3. DM was the most common disease in the known high-risk group (n = 153,050), followed by PAD (n = 89,807), and CHD (n = 65,868). In patients with newly defined high-risk for CVD, PAD (n = 55,767) was the most common disease followed by DM (n = 52,416), and CHD (n = 29,434) (Tables 2 and 3). Mean age was similar across patient groups (62–66 years; known high-risk and newly defined high-risk). For ACS (67.89%), CHD (52.82%), DM (52.31%) and AAD (62.87%), more than half of all patients were men; for stroke (49.53%) and PAD (47.66%), less than half of the patients were men.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics in subjects stratified by cardiovascular risk category and disease: known high-risk patients

| Stroke | ACS | CHD | PAD | DM | AAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 39,317) | (n = 5309) | (n = 65,868) | (n = 89,807) | (n = 153,050) | (n = 2200) | |

| Mean age, years (±SD) | 65.39 ± 9.43 | 65.09 ± 9.39 | 63.41 ± 9.21 | 63.79 ± 9.39 | 62.63 ± 9.11 | 66.45 ± 9.02 |

| Male, n (%) | 18,575 (47.24) | 3442 (64.83) | 34,431 (52.27) | 38,262 (42.6) | 80,104 (52.34) | 1380 (62.73) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (±SD) | 24.28 ± 3.16 | 24.35 ± 3.16 | 24.51 ± 3.08 | 24.33 ± 3.15 | 24.39 ± 3.11 | 24.05 ± 3.06 |

| Mean waist circumference, cm (±SD) | 83.5 ± 8.52 | 84.69 ± 8.37 | 83.94 ± 8.42 | 83.06 ± 8.5 | 83.69 ± 8.43 | 84.19 ± 8.47 |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||||

| non-smoker | 27,731 (71.56) | 3029 (58.07) | 43,183 (66.65) | 64,638 (72.92) | 99,636 (66.21) | 1291 (59.69) |

| former smoker | 6549 (16.90) | 1370 (26.27) | 12,980 (20.03) | 12,987 (14.65) | 27,958 (18.58) | 533 (24.64) |

| current smoker | 4474 (11.54) | 817 (15.66) | 8625 (13.31) | 11,012 (12.42) | 22,887 (15.21) | 339 (15.67) |

| DM, n (%) | 23,175 (58.94) | 3806 (71.69) | 38,946 (59.13) | 46,651 (51.95) | 153,050 (100.0) | 1477 (67.14) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 30,727 (78.15) | 4759 (89.64) | 52,413 (79.57) | 61,991 (69.03) | 102,151 (66.74) | 1918 (87.18) |

| Mean systolic BP, mmHg (±SD) | 128.08 ± 15.79 | 126.98 ± 16.2 | 127.34 ± 15.54 | 127.71 ± 15.71 | 127.37 ± 15.5 | 128.45 ± 16.43 |

| Mean diastolic BP, mmHg (±SD) | 78.06 ± 10.06 | 77.11 ± 10.24 | 77.8 ± 9.99 | 78.1 ± 9.99 | 77.9 ± 9.91 | 77.51 ± 10.23 |

| Mean total cholesterol, mg/dL (±SD) | 194.21 ± 40.18 | 177.03 ± 40.72 | 191.38 ± 39.68 | 198.2 ± 39.88 | 195.06 ± 39.69 | 183.39 ± 41.46 |

| Mean triglycerides, mg/dL (±SD) | 141.79 ± 83.48 | 139.2 ± 79.8 | 140.41 ± 83.85 | 141.98 ± 84.27 | 144.76 ± 88.7 | 134.63 ± 75.27 |

| Mean HDL-C level, mg/dL (±SD) | 53.6 ± 31.11 | 52.22 ± 36.79 | 53.45 ± 28.84 | 54.2 ± 27.02 | 53.47 ± 27.19 | 51.48 ± 21.36 |

| Mean LDL-C level, mg/dL (±SD) | 114.02 ± 38.97 | 99.71 ± 39.85 | 111.47 ± 39.52 | 116.79 ± 38.37 | 113.99 ± 38.62 | 106.1 ± 41.52 |

| Mean fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL (±SD) | 104.49 ± 29.4 | 108.7 ± 35.96 | 105.12 ± 29.52 | 104.62 ± 29.76 | 111.58 ± 35.65 | 106.7 ± 31.86 |

* Variables from the health screening program were included missing data. Missing rates (%) are 0.08 for BMI, 0.10 for waist circumference, 1.55 for Smoking, 0.04 for systolic BP, 0.04 for diastolic BP, 0.001 for total cholesterol, 0.08 for triglycerides, 0.004 for HDL-C level, 0.000 for LDL-C, and 0.002 for fasting plasma glucose

AAD atherosclerotic artery disease, ACS acute coronary syndrome, CHD coronary heart disease, DM diabetes mellitus, PAD peripheral artery disease

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics in subjects stratified by cardiovascular risk category and disease: newly defined high-risk patients

| Stroke | ACS | CHD | PAD | DM | AAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 17,410) | (n = 2479) | (n = 29,434) | (n = 55,767) | (n = 52,416) | (n = 4624) | |

| Mean age, years (±SD) | 65.22 ± 8.76 | 65.71 ± 8.8 | 63.61 ± 8.51 | 63.21 ± 8.41 | 61.92 ± 8.3 | 65.74 ± 8.18 |

| Male, n (%) | 8623 (49.53) | 1683 (67.89) | 15,547 (52.82) | 26,576 (47.66) | 27,417 (52.31) | 2907 (62.87) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (±SD) | 24.2 ± 2.96 | 24.47 ± 3.01 | 24.42 ± 3 | 24.25 ± 2.95 | 24.41 ± 3 | 24.21 ± 2.81 |

| Mean waist circumference, cm (±SD) | 82.99 ± 8.31 | 84.94 ± 8 | 83.44 ± 8.28 | 82.73 ± 8.29 | 83.09 ± 8.33 | 83.72 ± 8.07 |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||||

| non-smoker | 11,835 (68.66) | 1294 (52.84) | 19,085 (65.55) | 38,415 (69.63) | 33,675 (64.96) | 2636 (57.57) |

| former smoker | 3015 (17.49) | 536 (21.89) | 5679 (19.5) | 9508 (17.23) | 10,006 (19.3) | 1133 (24.74) |

| current smoker | 2387 (13.85) | 619 (25.28) | 4353 (14.95) | 7249 (13.14) | 8162 (15.74) | 810 (17.69) |

| DM, n (%) | 8393 (48.21) | 1274 (51.39) | 13,860 (47.09) | 24,589 (44.09) | 0 (0.00) | 2650 (57.31) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 10,910 (62.67) | 1708 (68.90) | 18,210 (61.87) | 32,098 (57.59) | 26,890 (51.30) | 3300 (71.37) |

| Mean systolic BP, mmHg (±SD) | 127.83 ± 15.67 | 129.22 ± 15.25 | 127.53 ± 15.42 | 126.89 ± 15.48 | 127.13 ± 15.46 | 128.4 ± 15.15 |

| Mean diastolic BP, mmHg (±SD) | 78.18 ± 10.04 | 78.41 ± 9.85 | 78.26 ± 10.03 | 77.86 ± 9.96 | 78.48 ± 10.06 | 77.78 ± 9.84 |

| Mean total cholesterol, mg/dL (±SD) | 199.09 ± 39 | 202.64 ± 43.09 | 199.54 ± 38.93 | 199.22 ± 38.59 | 203.88 ± 39.46 | 195.52 ± 40.2 |

| Mean triglycerides, mg/dL (±SD) | 140.53 ± 82.41 | 153.91 ± 88.65 | 141.5 ± 84.77 | 138.95 ± 83.78 | 146.67 ± 91.49 | 139.7 ± 80.57 |

| Mean HDL-C level, mg/dL (±SD) | 53.49 ± 23.68 | 50.51 ± 18.84 | 53.69 ± 24.23 | 54.42 ± 24.76 | 54.15 ± 22.38 | 52.06 ± 16.44 |

| Mean LDL-C level, mg/dL (±SD) | 118.37 ± 37.42 | 121.51 ± 39.64 | 118.52 ± 37.17 | 117.99 ± 37 | 121.2 ± 37.28 | 115.85 ± 37.4 |

| Mean fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL (±SD) | 103.58 ± 28.42 | 107.9 ± 33.18 | 103.76 ± 27.51 | 103.15 ± 27.36 | 106.94 ± 30.32 | 106.46 ± 29.8 |

* Variables from the health screening program were included missing data. Missing rates (%) for variables are 0.01 for BMI, 0.03 for waist circumference, 0.72 for Smoking, 0.02 for systolic BP, 0.02 for diastolic BP, 0.000 for total cholesterol, 0.09 for triglycerides, 0.002 for HDL-C level, 0.000 for LDL-C, and 0.001 for fasting plasma glucose

AAD atherosclerotic artery disease, ACS acute coronary syndrome, CHD coronary heart disease, DM diabetes mellitus, PAD peripheral artery disease

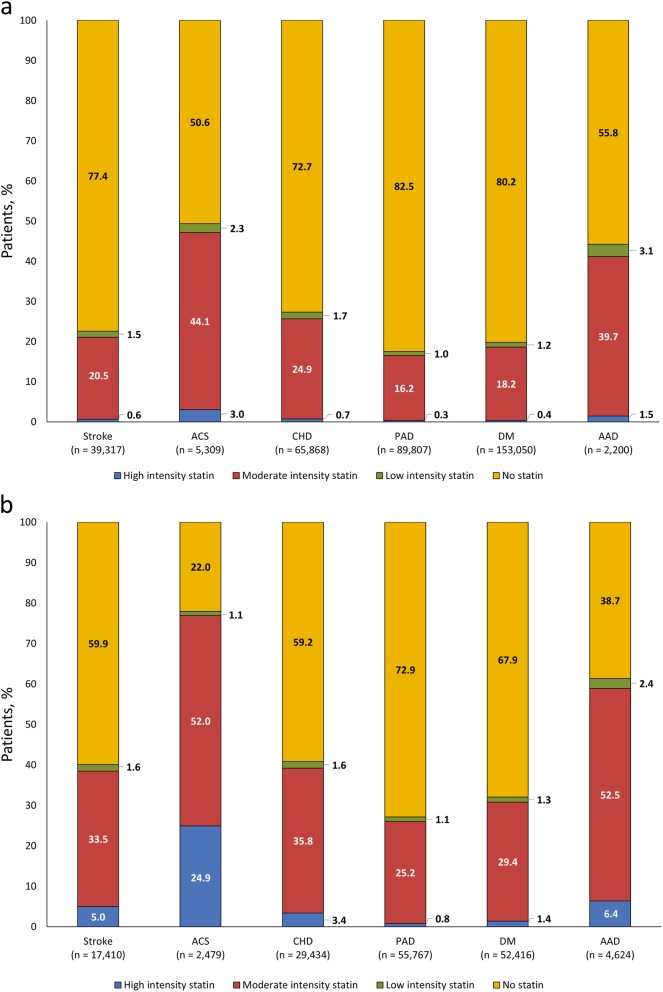

Statin use

Relatively low proportions of subjects were under lipid-lowering therapy with statin (21.5% [known high-risk], 34.4% [newly defined high-risk]). Among statin users, most patients in both the known and newly defined high-risk groups received moderate-intensity statin therapy (89.3–92.5%). High-intensity statin therapy was least commonly used in known high-risk patients, but more frequent in newly defined high-risk patients: 2.8 and 12.5% (stroke), 6.1 and 32.0% (ACS), 2.7 and 8.3% (CHD), 1.8 and 3.0% (PAD), 2.0 and 4.4% (DM), and 3.3 and 10.4% (AAD), respectively.

Overall, 22.6 and 40.1% of known high-risk and newly defined high-risk stroke patients, respectively, received statin therapy (Fig. 2). For stroke patients defined as the known high-risk group (n = 39,317), 1.5, 20.5 and 0.6% received low-, moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy, respectively. For stroke patients defined as the newly defined high-risk (n = 17,410), corresponding values were 1.6, 33.5 and 5.0%. Overall, 49.4% of ACS patients with known high-risk received statin therapy versus 78.0% of patients with newly defined high-risk. In ACS patients with known high-risk (n = 5309), 2.3, 44.1 and 3.0% received low-, moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy, respectively; corresponding values were 1.1, 52.0 and 24.9%, in ACS patients with newly defined high-risk (n = 2479). This difference was largely due to a higher proportion of newly defined high-risk patients receiving high-intensity statin therapy compared with known high-risk patients (24.9% vs. 3.0%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Statin use in cardiovascular high-risk groups: a. in known high-risk patients and b. in newly defined high-risk patients. AAD, atherosclerotic artery disease; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CHD, coronary heart disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; PAD, peripheral artery disease

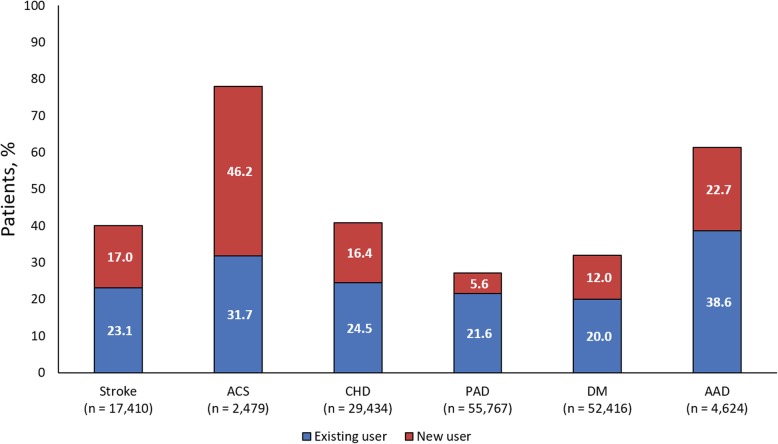

Statins were also used more frequently in newly defined high-risk patients compared with known high-risk patients in CHD (40.8% vs. 27.3%), PAD (27.1% vs. 17.5%), DM (32.1% vs. 19.8%) and AAD (61.3% vs. 44.2%) (Fig. 2). In newly defined high-risk stroke patients (n = 17,410), 23.1% were existing statin users and 17.0% were new statin users. In newly defined high-risk ACS patients (n = 2479), 31.7% were existing users, and 46.2% were new users (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Patients previously receiving statins (existing user) or newly prescribed statins (new user)

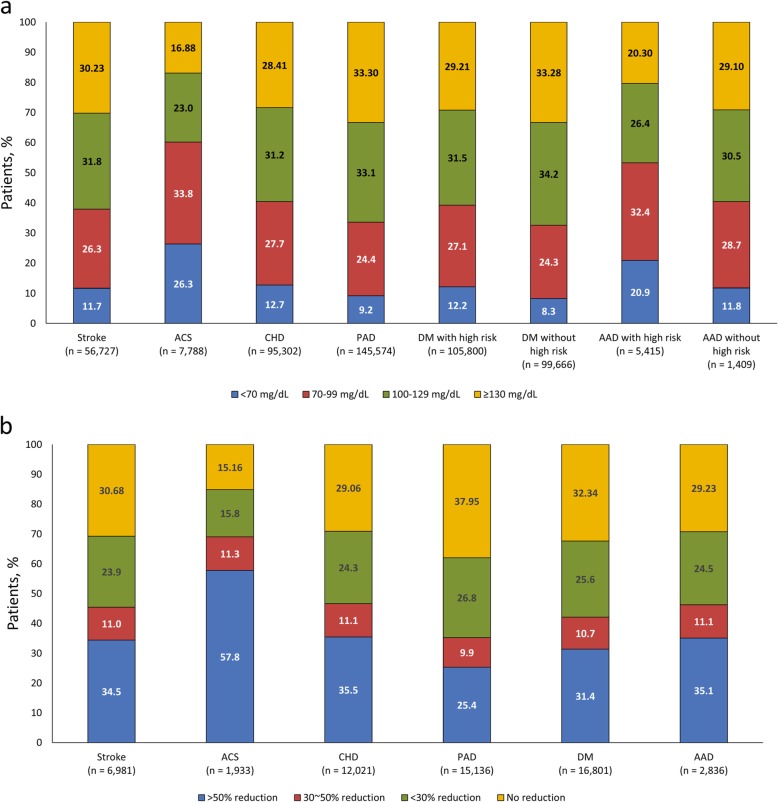

LDL-C goal attainment rates

LDL-C goal attainment rates in all high-risk patients (known plus newly defined), defined according to target LDL-C level and stratified by disease, are shown in Fig. 4a. LDL-C goal attainment rates in stroke patients (n = 56,727) for < 70 mg/dL were 11.7%; and in ACS patients (n = 7788) were 26.3%. In CHD patients (n = 95,302), LDL-C attainment rates for < 70 mg/dL were 12.7%; and, in PAD patients (n = 145,574), were 9.2% (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

LDL-C goal attainment rates in a. all high-risk (known + newly defined high-risk patients) by target LDL-C level and b. in newly defined high-risk patients stratified by disease by reduction rate

Attainment rates for DM patients with a high-risk for CVD (n = 105,800) were higher for achieving < 70 mg/dL goals than for DM patients without high risk (n = 99,666) (12.2% vs. 8.3%, respectively). Attainment rates for ≥70 to < 100 mg/dL (27.1% vs. 24.3%) were comparable. Similarly, a higher proportion of patients with AAD with high-risk (n = 5415) achieved < 70 mg/dL goals than patients without high risk (n = 1409) (20.9% vs. 11.8%). Respective attainment rates for ≥70 to < 100 mg/dL were 32.4% versus 28.7% (Fig. 4a).

In newly defined high-risk patients, LDL-C goal attainment was defined as an LDL-C reduction > 50%, according to ACC/AHA guidelines [3] (Fig. 4b). These goals were achieved in 34.5% of 6981 stroke patients, 57.8% of 1933 ACS patients, 35.5% of CHD patients (n = 12,021), 25.4% of PAD patients (n = 15,136), 31.4% of DM patients (n = 16,801), and by 35.1% of AAD patients (n = 2836) (Fig. 4b).

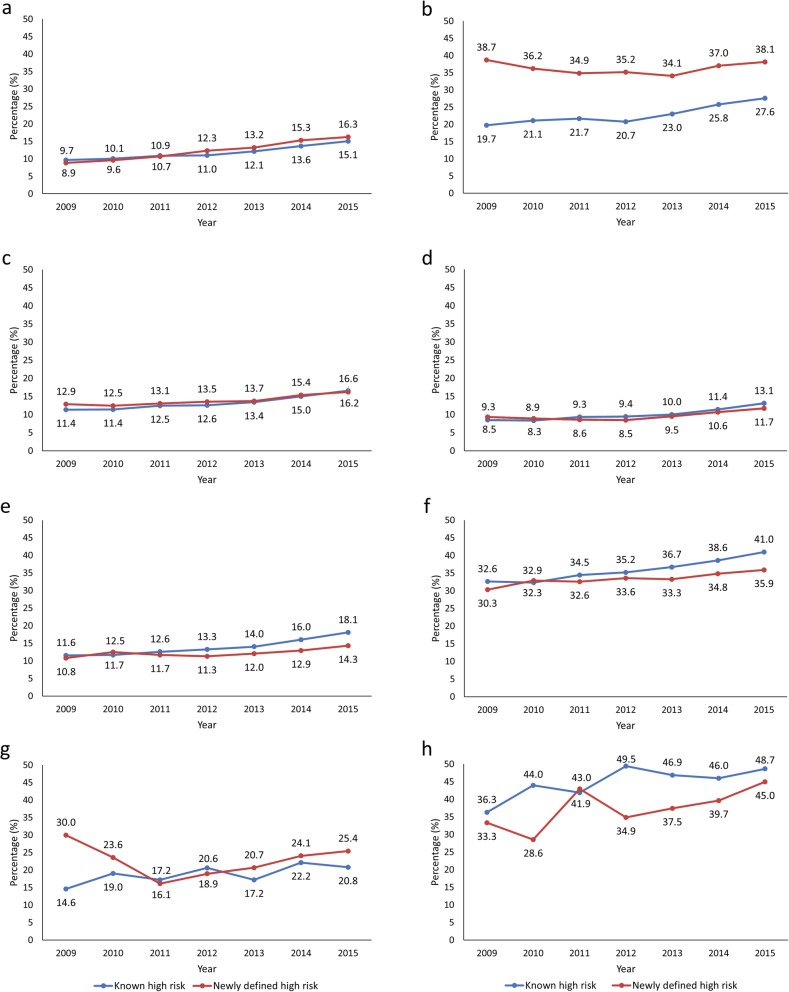

Time trends of LDL-C goal attainment in known and newly defined high-risk patients in each disease group are shown in Fig. 5. In stroke patients, there were similar upward trends from 2009 to 2015 in both known (from 9.7 to 15.1%) and newly defined (from 8.9 to 16.3%) high-risk patients. In contrast, in ACS patients, the proportion of known high-risk patients achieving LDL-C goals increased steadily from 2009 to 2015 (from 19.7 to 27.6%), whereas the proportion of newly defined high-risk patients remained reasonably constant (38.7% in 2009 and 38.1% in 2015).

Fig. 5.

Time trends of goal attainment in known and newly defined high-risk patients with a. stroke; b. ACS; c. CHD; d. PAD; e. DM with high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD); f. DM without high risk of CVD; g. AAD with high risk of CVD; h. AAD without high risk of CVD. P for trend of known high-risk and newly defined high-risk, respectively. a. < .0001 and < .0001; b. <.0001 and 0.1081; c. <.0001 and < .0001; d. <.0001 and < .0001; e. <.0001 and < .0001; f. <.0001 and < .0001; g. 0.0027 and < .0001; h. 0.0226 and 0.0138

In CHD and PAD patients, the time-trend curves for known and newly defined high-risk patients were virtually superimposable. In CHD patients, LDL-C goal attainment steadily increased from 2009 to 2015: from 11.4 to 16.6% in known, and 12.9 to 16.2% in newly defined high-risk patients. In PAD patients, goal attainment rates from 2009 to 2015 were 8.5 to 13.1% in known, and 9.3 to 11.7% in newly defined high-risk patients (Fig. 5).

Time trends in DM patients with or without high-risk showed that DM patients without high-risk consistently had higher LDL-C goal attainment rates than DM patients with high-risk, irrespective of the known or recent diagnosis of high-risk. Attainment rates in 2015 for DM patients without high-risk were 41.0 and 35.9%, respectively, for known and newly defined high-risk groups, compared with rates of 18.1 and 14.3% for newly defined high-risk groups in DM patients with high-risk (Fig. 5).

Attainment rates of atherosclerosis patients with high-risk were generally similar in newly defined high-risk patients (16.1% in 2011, 25.4% in 2015) compared with known high-risk patients (14.6% in 2011, 20.8% in 2015), although the attainment rate tended to be higher in newly defined high-risk than in known high-risk in 2009. However, in atherosclerosis without high-risk, attainment rates were generally higher in known high-risk patients (36.3% in 2009, 48.7% in 2015) than in newly defined high-risk patients (33.3% in 2009, 45.0% in 2015) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This retrospective study using the Korean NHIS-HEALS large number database addressed that dyslipidemia management in patients with high-risk for CVD needs to be improved. Although ACS patients who were newly defined high-risk group was the most controlled among the groups (34.4%), the control of LDL-C levels is still not good enough considering consequence CVD risks and its disease burden. Based on the key findings from this study, LDL-cholesterol level reduction treatment strategies and “treat to-target” groups need to be clarified.

Statin use was highest in patients with ACS or AAD. Overall, 49.4 and 78.0% of ACS patients with known and newly defined high-risk received statins, respectively, whereas respective figures for patients with AAD were 44.2 and 61.3%. A recent US study found that, although around 90% of high-risk patients started treatment with statin monotherapy, treatment initiation with high-intensity statins was ≤10% [27]. In present study, most patients received moderate-intensity statin therapy; in general, < 10% of patients received high-intensity statin therapy. The exception was ACS patients with newly defined high-risk, of whom 24.9% received high-intensity statin therapy.

Guidelines for lipid management in ACS patients vary, and target values, have changed in recent years. 2013 ACC/AHA and 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Guidelines recommend high-intensity statin therapy, which lowers LDL-C levels on average by approximately ≥50%, and moderate-intensity statin therapy, which lowers LDL-C on average by approximately 30 to < 50% for patients aged > 75 years or who are not candidates for high-intensity statin therapy [3, 28]. These guidelines are also applicable to patients with stroke or other clinical ASCVD events [3, 28]. Current 2018 Korean guidelines recommend LDL-C treatment goals dependent on risk assessment: very high-risk < 70 mg/dL, high-risk < 100 mg/dL, moderate-risk < 130 mg/dL, and low-risk < 160 mg/dL [23]. Using 2013 ACC/AHA guideline target values [3], goal attainment rates were relatively high compared to those using the 2018 Korean guidelines, even in the newly defined high-risk patient group (data not shown). For example, in ACS, LDL-C goal attainment rate was 26.3% by target LDL-C level and 57.8% by reduction rate. One possible explanation is that doctors treating high-risk patients consider that LDL-C 100 mg/dL is a sufficiently low attainment level for dyslipidemia treatment, although data derived from KNHANES (2014–2016) show that 17.6% of adult Koreans (aged ≥30 years) had hyper-LDL cholesterolemia (LDL-C ≥ 160 mg/dL) [8]. On the other hand, the higher attainment rate by reduction rate than by target LDL-C level, even though most high-risk patients received moderate intensity statin, may be related to higher statin efficacy in Asians compared to Caucasians [29–32]. Further studies are warranted for more appropriate secondary prevention in high-risk patients.

Time-trend (2009–2015) for LDL-C goal attainment were similar for comparisons of known and newly defined high-risk patients with stroke, CHD, PAD, AAD with additional high-risk disease or DM with/without additional high-risk disease. In ACS, newly defined high-risk patients had consistently higher attainment rates from 2009 to 2015 compared to known high-risk patients. Although reasons for differences were not assessed in this study, they possibly reflect patient medication adherence issues [33, 34], and/or suboptimal performance and poor perception of physicians regarding attainment rates [35], resulting in patients receiving inadequate dosages or titration of lipid-lowering medication [36, 37]. On the other hand, even though the achievement rate was relatively high in newly defined ACS patients, the gap had been narrowing due to no improvement in newly defined ACS patient. It also reflects suboptimal perception of physicians [35] in newly diagnosed cases, but, further consideration is needed for causes of no improvement of goal attainment in newly defined ACS patients, in contrast to the increase in known ACS patients.

There have been clinical practice changes due to changes in the guidelines such as ACC/AHA [3] and ESC/EAS [15] since the NCEP-ATP III guideline [2]. It was expected that the use of high-intensity statins and the achievement of LDL-C targets in the groups of the high-risk and very high-risk increased. Although the time trends of LDL-C goal attainment had been generally increasing in all groups except newly defined ACS patients, most patients did not achieve LDL-C targets. Attainment rates were < 50% for patients in each disease category, including the best LDL-C target attainment shown in ACS patients. Even in a previous Korean study of diabetic patients treated by specialists, the LDL-C goal attainment in patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy was low at 47.4% in 2010 [35]. Comparable results (for 2010) in this study showed LDL-C goal attainment rates of approximately 12 and 32%, in DM patients with or without additional high-risk disease, respectively. Low rates of LDL-C goal attainment have also been described consistently in other countries, including 58% of recent ACS patients in the Netherlands [38], 28.8% of ACS survivors in Hong Kong and Taiwan [39], 30% of German atherosclerotic CVD patients [40], 41% of patients with DM at very-high cardiovascular risk receiving statins in France [41] and 38% of DM patients with ischemic heart disease in a tertiary hospital in China [42]. In contrast, a higher attainment rate (68%) for Japan Atherosclerosis Society guideline-recommended LDL-C targets [43] was reported in high-risk patients for CVD in Japan [44].

This study has several strengths. The current study is derived from a nationally-representative cohort of Korean individuals (NHIS-HEALS database, n = 514,866) with a relatively low attrition rate [24], reflecting real-world clinical circumstances. Because information on drug use and bio-clinical laboratory results were included in databases, the risk of recall bias was eliminated. Considering the lack of data in Asian populations for estimating LDL-C goal achievement, results of this study provide information on possible LDL-C reduction rates. In addition, the estimation of goal attainment rate by LDL-C level (< 70 mg/dL, 70–100 mg/dL for target goal) and by percent of LDL-C reduction, together in a large national cohort, is valuable.

However, this study also has some limitations. The result needed to be interpreted with consideration of followings; Subjects were selected based on the availability of LDL-C measurements, which may limit the generalizability of results to general population. Additionally, the age of participant limited between 40 and 70 years and it may not be applicable to goal attainment of young adult participants, or oldest-old participants. In addition, due to the nature of the NHIS-HEALS database, disease diagnosis variables may reflect healthcare usage which is sensitive to the fee-for-service payment and reimbursement system in Korea, rather than being an accurate reflection of a patient’s specific medical condition.

Conclusions

LDL-C goal attainment rates in Korean patients with CVD or with a high-risk for CVD are still poor, with < 50% of patients achieving LDL-C targets. Proactive action is needed to improve dyslipidemia management in high-risk patients with CVD, including those with stroke or ACS.

Acknowledgments

Initial draft preparation and editorial assistance, under the guidance and corrections of the authors, was provided by Robert A. Furlong PhD and David P. Figgitt PhD, ISMPP CMPP™, Content Ed Net, with funding from Amgen Inc.

Abbreviations

- AAD

Atherosclerotic artery disease

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ASCVD

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BMI

Body mass index

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- EAS

European Atherosclerosis Society

- ESC

European Society of Cardiology

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ICD

International Classification of Disease

- IRB

Institutional review board

- KNHANES

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NCEP-ATP

National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel

- NHIS-HEALS

National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort

- PAD

Peripheral artery disease

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

All of the listed authors satisfied the following ICMJE guidelines: (1) conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted, and (4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from Amgen, Inc.

Availability of data and materials

The National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) was third party data owned by the National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC). Interested researchers can contact NHIC to access the data in the following ways: Tel: 82–33–736-2469 (Big data operation room, NHIC), Web: https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba006cv.do.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used an existing database, which was anonymized, with subjects’ details untraceable during analysis. Consequently, no informed consent or data monitoring process was required for this study. This study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, and IRB-approved as exempt (IRB number: X-1801-447-903).

Consent for publication

No informed consent or data monitoring process was required for this study.

Competing interests

Ye Seul Yang, Bo Ram Yang and Mi-Sook Kim have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article. Sung Hee Choi received research funding from Amgen (Amgen study number: 20170708) and Yunji Hwang is employed by Amgen.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ye Seul Yang and Bo Ram Yang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) 2017 (accessed 15 Nov 2018).

- 2.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889–934. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(Suppl 2):1–87. doi: 10.4158/EP171764.APPGL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopin L, Lowenstein C. Dyslipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:ITC81–ITC96. doi: 10.7326/AITC201712050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Haidong, Naghavi Mohsen, Allen Christine, Barber Ryan M, Bhutta Zulfiqar A, Carter Austin, Casey Daniel C, Charlson Fiona J, Chen Alan Zian, Coates Matthew M, Coggeshall Megan, Dandona Lalit, Dicker Daniel J, Erskine Holly E, Ferrari Alize J, Fitzmaurice Christina, Foreman Kyle, Forouzanfar Mohammad H, Fraser Maya S, Fullman Nancy, Gething Peter W, Goldberg Ellen M, Graetz Nicholas, Haagsma Juanita A, Hay Simon I, Huynh Chantal, Johnson Catherine O, Kassebaum Nicholas J, Kinfu Yohannes, Kulikoff Xie Rachel, Kutz Michael, Kyu Hmwe H, Larson Heidi J, Leung Janni, Liang Xiaofeng, Lim Stephen S, Lind Margaret, Lozano Rafael, Marquez Neal, Mensah George A, Mikesell Joe, Mokdad Ali H, Mooney Meghan D, Nguyen Grant, Nsoesie Elaine, Pigott David M, Pinho Christine, Roth Gregory A, Salomon Joshua A, Sandar Logan, Silpakit Naris, Sligar Amber, Sorensen Reed J D, Stanaway Jeffrey, Steiner Caitlyn, Teeple Stephanie, Thomas Bernadette A, Troeger Christopher, VanderZanden Amelia, Vollset Stein Emil, Wanga Valentine, Whiteford Harvey A, Wolock Timothy, Zoeckler Leo, Abate Kalkidan Hassen, Abbafati Cristiana, Abbas Kaja M, Abd-Allah Foad, Abera Semaw Ferede, Abreu Daisy M X, Abu-Raddad Laith J, Abyu Gebre Yitayih, Achoki Tom, Adelekan Ademola Lukman, Ademi Zanfina, Adou Arsène Kouablan, Adsuar José C, Afanvi Kossivi Agbelenko, Afshin Ashkan, Agardh Emilie Elisabet, Agarwal Arnav, Agrawal Anurag, Kiadaliri Aliasghar Ahmad, Ajala Oluremi N, Akanda Ali Shafqat, Akinyemi Rufus Olusola, Akinyemiju Tomi F, Akseer Nadia, Lami Faris Hasan Al, Alabed Samer, Al-Aly Ziyad, Alam Khurshid, Alam Noore K M, Alasfoor Deena, Aldhahri Saleh Fahed, Aldridge Robert William, Alegretti Miguel Angel, Aleman Alicia V, Alemu Zewdie Aderaw, Alexander Lily T, Alhabib Samia, Ali Raghib, Alkerwi Ala'a, Alla François, Allebeck Peter, Al-Raddadi Rajaa, Alsharif Ubai, Altirkawi Khalid A, Martin Elena Alvarez, Alvis-Guzman Nelson, Amare Azmeraw T, Amegah Adeladza Kofi, Ameh Emmanuel A, Amini Heresh, Ammar Walid, Amrock Stephen Marc, Andersen Hjalte H, Anderson Benjamin O, Anderson Gregory M, Antonio Carl Abelardo T, Aregay Atsede Fantahun, Ärnlöv Johan, Arsenijevic Valentina S Arsic, Artaman Al, Asayesh Hamid, Asghar Rana Jawad, Atique Suleman, Avokpaho Euripide Frinel G Arthur, Awasthi Ashish, Azzopardi Peter, Bacha Umar, Badawi Alaa, Bahit Maria C, Balakrishnan Kalpana, Banerjee Amitava, Barac Aleksandra, Barker-Collo Suzanne L, Bärnighausen Till, Barregard Lars, Barrero Lope H, Basu Arindam, Basu Sanjay, Bayou Yibeltal Tebekaw, Bazargan-Hejazi Shahrzad, Beardsley Justin, Bedi Neeraj, Beghi Ettore, Belay Haileeyesus Adamu, Bell Brent, Bell Michelle L, Bello Aminu K, Bennett Derrick A, Bensenor Isabela M, Berhane Adugnaw, Bernabé Eduardo, Betsu Balem Demtsu, Beyene Addisu Shunu, Bhala Neeraj, Bhalla Ashish, Biadgilign Sibhatu, Bikbov Boris, Abdulhak Aref A Bin, Biroscak Brian J, Biryukov Stan, Bjertness Espen, Blore Jed D, Blosser Christopher D, Bohensky Megan A, Borschmann Rohan, Bose Dipan, Bourne Rupert R A, Brainin Michael, Brayne Carol E G, Brazinova Alexandra, Breitborde Nicholas J K, Brenner Hermann, Brewer Jerry D, Brown Alexandria, Brown Jonathan, Brugha Traolach S, Buckle Geoffrey Colin, Butt Zahid A, Calabria Bianca, Campos-Nonato Ismael Ricardo, Campuzano Julio Cesar, Carapetis Jonathan R, Cárdenas Rosario, Carpenter David O, Carrero Juan Jesus, Castañeda-Orjuela Carlos A, Rivas Jacqueline Castillo, Catalá-López Ferrán, Cavalleri Fiorella, Cercy Kelly, Cerda Jorge, Chen Wanqing, Chew Adrienne, Chiang Peggy Pei-Chia, Chibalabala Mirriam, Chibueze Chioma Ezinne, Chimed-Ochir Odgerel, Chisumpa Vesper Hichilombwe, Choi Jee-Young Jasmine, Chowdhury Rajiv, Christensen Hanne, Christopher Devasahayam Jesudas, Ciobanu Liliana G, Cirillo Massimo, Cohen Aaron J, Colistro Valentina, Colomar Mercedes, Colquhoun Samantha M, Cooper Cyrus, Cooper Leslie Trumbull, Cortinovis Monica, Cowie Benjamin C, Crump John A, Damsere-Derry James, Danawi Hadi, Dandona Rakhi, Daoud Farah, Darby Sarah C, Dargan Paul I, das Neves José, Davey Gail, Davis Adrian C, Davitoiu Dragos V, de Castro E Filipa, de Jager Pieter, Leo Diego De, Degenhardt Louisa, Dellavalle Robert P, Deribe Kebede, Deribew Amare, Dharmaratne Samath D, Dhillon Preet K, Diaz-Torné Cesar, Ding Eric L, dos Santos Kadine Priscila Bender, Dossou Edem, Driscoll Tim R, Duan Leilei, Dubey Manisha, Duncan Bruce Bartholow, Ellenbogen Richard G, Ellingsen Christian Lycke, Elyazar Iqbal, Endries Aman Yesuf, Ermakov Sergey Petrovich, Eshrati Babak, Esteghamati Alireza, Estep Kara, Faghmous Imad D A, Fahimi Saman, Faraon Emerito Jose Aquino, Farid Talha A, Farinha Carla Sofia e Sa, Faro André, Farvid Maryam S, Farzadfar Farshad, Feigin Valery L, Fereshtehnejad Seyed-Mohammad, Fernandes Jefferson G, Fernandes Joao C, Fischer Florian, Fitchett Joseph R A, Flaxman Abraham, Foigt Nataliya, Fowkes F Gerry R, Franca Elisabeth Barboza, Franklin Richard C, Friedman Joseph, Frostad Joseph, Fürst Thomas, Futran Neal D, Gall Seana L, Gambashidze Ketevan, Gamkrelidze Amiran, Ganguly Parthasarathi, Gankpé Fortuné Gbètoho, Gebre Teshome, Gebrehiwot Tsegaye Tsewelde, Gebremedhin Amanuel Tesfay, Gebru Alemseged Aregay, Geleijnse Johanna M, Gessner Bradford D, Ghoshal Aloke Gopal, Gibney Katherine B, Gillum Richard F, Gilmour Stuart, Giref Ababi Zergaw, Giroud Maurice, Gishu Melkamu Dedefo, Giussani Giorgia, Glaser Elizabeth, Godwin William W, Gomez-Dantes Hector, Gona Philimon, Goodridge Amador, Gopalani Sameer Vali, Gosselin Richard A, Gotay Carolyn C, Goto Atsushi, Gouda Hebe N, Greaves Felix, Gugnani Harish Chander, Gupta Rahul, Gupta Rajeev, Gupta Vipin, Gutiérrez Reyna A, Hafezi-Nejad Nima, Haile Demewoz, Hailu Alemayehu Desalegne, Hailu Gessessew Bugssa, Halasa Yara A, Hamadeh Randah Ribhi, Hamidi Samer, Hancock Jamie, Handal Alexis J, Hankey Graeme J, Hao Yuantao, Harb Hilda L, Harikrishnan Sivadasanpillai, Haro Josep Maria, Havmoeller Rasmus, Heckbert Susan R, Heredia-Pi Ileana Beatriz, Heydarpour Pouria, Hilderink Henk B M, Hoek Hans W, Hogg Robert S, Horino Masako, Horita Nobuyuki, Hosgood H Dean, Hotez Peter J, Hoy Damian G, Hsairi Mohamed, Htet Aung Soe, Htike Maung Maung Than, Hu Guoqing, Huang Cheng, Huang Hsiang, Huiart Laetitia, Husseini Abdullatif, Huybrechts Inge, Huynh Grace, Iburg Kim Moesgaard, Innos Kaire, Inoue Manami, Iyer Veena J, Jacobs Troy A, Jacobsen Kathryn H, Jahanmehr Nader, Jakovljevic Mihajlo B, James Peter, Javanbakht Mehdi, Jayaraman Sudha P, Jayatilleke Achala Upendra, Jeemon Panniyammakal, Jensen Paul N, Jha Vivekanand, Jiang Guohong, Jiang Ying, Jibat Tariku, Jimenez-Corona Aida, Jonas Jost B, Joshi Tushar Kant, Kabir Zubair, Kamal Ritul, Kan Haidong, Kant Surya, Karch André, Karema Corine Kakizi, Karimkhani Chante, Karletsos Dimitris, Karthikeyan Ganesan, Kasaeian Amir, Katibeh Marzieh, Kaul Anil, Kawakami Norito, Kayibanda Jeanne Françoise, Keiyoro Peter Njenga, Kemmer Laura, Kemp Andrew Haddon, Kengne Andre Pascal, Keren Andre, Kereselidze Maia, Kesavachandran Chandrasekharan Nair, Khader Yousef Saleh, Khalil Ibrahim A, Khan Abdur Rahman, Khan Ejaz Ahmad, Khang Young-Ho, Khera Sahil, Khoja Tawfik Ahmed Muthafer, Kieling Christian, Kim Daniel, Kim Yun Jin, Kissela Brett M, Kissoon Niranjan, Knibbs Luke D, Knudsen Ann Kristin, Kokubo Yoshihiro, Kolte Dhaval, Kopec Jacek A, Kosen Soewarta, Koul Parvaiz A, Koyanagi Ai, Krog Norun Hjertager, Defo Barthelemy Kuate, Bicer Burcu Kucuk, Kudom Andreas A, Kuipers Ernst J, Kulkarni Veena S, Kumar G Anil, Kwan Gene F, Lal Aparna, Lal Dharmesh Kumar, Lalloo Ratilal, Lallukka Tea, Lam Hilton, Lam Jennifer O, Langan Sinead M, Lansingh Van C, Larsson Anders, Laryea Dennis Odai, Latif Asma Abdul, Lawrynowicz Alicia Elena Beatriz, Leigh James, Levi Miriam, Li Yongmei, Lindsay M Patrice, Lipshultz Steven E, Liu Patrick Y, Liu Shiwei, Liu Yang, Lo Loon-Tzian, Logroscino Giancarlo, Lotufo Paulo A, Lucas Robyn M, Lunevicius Raimundas, Lyons Ronan A, Ma Stefan, Machado Vasco Manuel Pedro, Mackay Mark T, MacLachlan Jennifer H, Razek Hassan Magdy Abd El, Magdy Mohammed, Razek Abd El, Majdan Marek, Majeed Azeem, Malekzadeh Reza, Manamo Wondimu Ayele Ayele, Mandisarisa John, Mangalam Srikanth, Mapoma Chabila C, Marcenes Wagner, Margolis David Joel, Martin Gerard Robert, Martinez-Raga Jose, Marzan Melvin Barrientos, Masiye Felix, Mason-Jones Amanda J, Massano João, Matzopoulos Richard, Mayosi Bongani M, McGarvey Stephen Theodore, McGrath John J, McKee Martin, McMahon Brian J, Meaney Peter A, Mehari Alem, Mehndiratta Man Mohan, Mejia-Rodriguez Fabiola, Mekonnen Alemayehu B, Melaku Yohannes Adama, Memiah Peter, Memish Ziad A, Mendoza Walter, Meretoja Atte, Meretoja Tuomo J, Mhimbira Francis Apolinary, Micha Renata, Millear Anoushka, Miller Ted R, Mirarefin Mojde, Misganaw Awoke, Mock Charles N, Mohammad Karzan Abdulmuhsin, Mohammadi Alireza, Mohammed Shafiu, Mohan Viswanathan, Mola Glen Liddell D, Monasta Lorenzo, Hernandez Julio Cesar Montañez, Montero Pablo, Montico Marcella, Montine Thomas J, Moradi-Lakeh Maziar, Morawska Lidia, Morgan Katherine, Mori Rintaro, Mozaffarian Dariush, Mueller Ulrich O, Murthy Gudlavalleti Venkata Satyanarayana, Murthy Srinivas, Musa Kamarul Imran, Nachega Jean B, Nagel Gabriele, Naidoo Kovin S, Naik Nitish, Naldi Luigi, Nangia Vinay, Nash Denis, Nejjari Chakib, Neupane Subas, Newton Charles R, Newton John N, Ng Marie, Ngalesoni Frida Namnyak, de Dieu Ngirabega Jean, Nguyen Quyen Le, Nisar Muhammad Imran, Pete Patrick Martial Nkamedjie, Nomura Marika, Norheim Ole F, Norman Paul E, Norrving Bo, Nyakarahuka Luke, Ogbo Felix Akpojene, Ohkubo Takayoshi, Ojelabi Foluke Adetola, Olivares Pedro R, Olusanya Bolajoko Olubukunola, Olusanya Jacob Olusegun, Opio John Nelson, Oren Eyal, Ortiz Alberto, Osman Majdi, Ota Erika, Ozdemir Raziye, PA Mahesh, Pain Amanda, Pandian Jeyaraj D, Pant Puspa Raj, Papachristou Christina, Park Eun-Kee, Park Jae-Hyun, Parry Charles D, Parsaeian Mahboubeh, Caicedo Angel J Paternina, Patten Scott B, Patton George C, Paul Vinod K, Pearce Neil, Pedro João Mário, Stokic Ljiljana Pejin, Pereira David M, Perico Norberto, Pesudovs Konrad, Petzold Max, Phillips Michael Robert, Piel Frédéric B, Pillay Julian David, Plass Dietrich, Platts-Mills James A, Polinder Suzanne, Pope C Arden, Popova Svetlana, Poulton Richie G, Pourmalek Farshad, Prabhakaran Dorairaj, Qorbani Mostafa, Quame-Amaglo Justice, Quistberg D Alex, Rafay Anwar, Rahimi Kazem, Rahimi-Movaghar Vafa, Rahman Mahfuzar, Rahman Mohammad Hifz Ur, Rahman Sajjad Ur, Rai Rajesh Kumar, Rajavi Zhale, Rajsic Sasa, Raju Murugesan, Rakovac Ivo, Rana Saleem M, Ranabhat Chhabi L, Rangaswamy Thara, Rao Puja, Rao Sowmya R, Refaat Amany H, Rehm Jürgen, Reitsma Marissa B, Remuzzi Giuseppe, Resnikoff Serge, Ribeiro Antonio L, Ricci Stefano, Blancas Maria Jesus Rios, Roberts Bayard, Roca Anna, Rojas-Rueda David, Ronfani Luca, Roshandel Gholamreza, Rothenbacher Dietrich, Roy Ambuj, Roy Nawal K, Ruhago George Mugambage, Sagar Rajesh, Saha Sukanta, Sahathevan Ramesh, Saleh Muhammad Muhammad, Sanabria Juan R, Sanchez-Niño Maria Dolores, Sanchez-Riera Lidia, Santos Itamar S, Sarmiento-Suarez Rodrigo, Sartorius Benn, Satpathy Maheswar, Savic Miloje, Sawhney Monika, Schaub Michael P, Schmidt Maria Inês, Schneider Ione J C, Schöttker Ben, Schutte Aletta E, Schwebel David C, Seedat Soraya, Sepanlou Sadaf G, Servan-Mori Edson E, Shackelford Katya A, Shaddick Gavin, Shaheen Amira, Shahraz Saeid, Shaikh Masood Ali, Shakh-Nazarova Marina, Sharma Rajesh, She Jun, Sheikhbahaei Sara, Shen Jiabin, Shen Ziyan, Shepard Donald S, Sheth Kevin N, Shetty Balakrishna P, Shi Peilin, Shibuya Kenji, Shin Min-Jeong, Shiri Rahman, Shiue Ivy, Shrime Mark G, Sigfusdottir Inga Dora, Silberberg Donald H, Silva Diego Augusto Santos, Silveira Dayane Gabriele Alves, Silverberg Jonathan I, Simard Edgar P, Singh Abhishek, Singh Gitanjali M, Singh Jasvinder A, Singh Om Prakash, Singh Prashant Kumar, Singh Virendra, Soneji Samir, Søreide Kjetil, Soriano Joan B, Sposato Luciano A, Sreeramareddy Chandrashekhar T, Stathopoulou Vasiliki, Stein Dan J, Stein Murray B, Stranges Saverio, Stroumpoulis Konstantinos, Sunguya Bruno F, Sur Patrick, Swaminathan Soumya, Sykes Bryan L, Szoeke Cassandra E I, Tabarés-Seisdedos Rafael, Tabb Karen M, Takahashi Ken, Takala Jukka S, Talongwa Roberto Tchio, Tandon Nikhil, Tavakkoli Mohammad, Taye Bineyam, Taylor Hugh R, Ao Braden J Te, Tedla Bemnet Amare, Tefera Worku Mekonnen, Have Margreet Ten, Terkawi Abdullah Sulieman, Tesfay Fisaha Haile, Tessema Gizachew Assefa, Thomson Alan J, Thorne-Lyman Andrew L, Thrift Amanda G, Thurston George D, Tillmann Taavi, Tirschwell David L, Tonelli Marcello, Topor-Madry Roman, Topouzis Fotis, Towbin Jeffrey Allen, Traebert Jefferson, Tran Bach Xuan, Truelsen Thomas, Trujillo Ulises, Tura Abera Kenay, Tuzcu Emin Murat, Uchendu Uche S, Ukwaja Kingsley N, Undurraga Eduardo A, Uthman Olalekan A, Dingenen Rita Van, van Donkelaar Aaron, Vasankari Tommi, Vasconcelos Ana Maria Nogales, Venketasubramanian Narayanaswamy, Vidavalur Ramesh, Vijayakumar Lakshmi, Villalpando Salvador, Violante Francesco S, Vlassov Vasiliy Victorovich, Wagner Joseph A, Wagner Gregory R, Wallin Mitchell T, Wang Linhong, Watkins David A, Weichenthal Scott, Weiderpass Elisabete, Weintraub Robert G, Werdecker Andrea, Westerman Ronny, White Richard A, Wijeratne Tissa, Wilkinson James D, Williams Hywel C, Wiysonge Charles Shey, Woldeyohannes Solomon Meseret, Wolfe Charles D A, Won Sungho, Wong John Q, Woolf Anthony D, Xavier Denis, Xiao Qingyang, Xu Gelin, Yakob Bereket, Yalew Ayalnesh Zemene, Yan Lijing L, Yano Yuichiro, Yaseri Mehdi, Ye Pengpeng, Yebyo Henock Gebremedhin, Yip Paul, Yirsaw Biruck Desalegn, Yonemoto Naohiro, Yonga Gerald, Younis Mustafa Z, Yu Shicheng, Zaidi Zoubida, Zaki Maysaa El Sayed, Zannad Faiez, Zavala Diego E, Zeeb Hajo, Zeleke Berihun M, Zhang Hao, Zodpey Sanjay, Zonies David, Zuhlke Liesl Joanna, Vos Theo, Lopez Alan D, Murray Christopher J L. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joseph P, Leong D, McKee M, Anand SS, Schwalm JD, Teo K, et al. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: the epidemiology and risk factors. Circ Res. 2017;121(6):677–694. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.308903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis. Dyslipidemia Fact Sheets in Korea 2018. http://www.lipid.or.kr/bbs/?code=fact_sheet. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Roh E, Ko SH, Kwon HS, Kim NH, Kim JH, Kim CS, et al. Prevalence and Management of Dyslipidemia in Korea: Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey during 1998 to 2010. Diabetes Metab J. 2013;37(6):433–449. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2013.37.6.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YH, Lee SG, Lee MH, Kim JH, Lee BW, Kang ES, et al. Serum cholesterol concentration and prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the Korea National Health and nutrition examination surveys 2008-2010: beyond the tip of the iceberg. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1):e000650. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong JS, Kwon HS. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of dyslipidemia in Koreans. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2017;32(1):30–35. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Son H, Ryu OH. Management status of cardiovascular disease risk factors for dyslipidemia among Korean adults. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58(2):326–338. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee for the Korean Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia. 2015 Korean Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia: Executive Summary (English Translation). Korean Circ J. 2016;46:275–305. 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Pearson GJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dawes M, et al. 2016 Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(11):1263–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.07.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, Wiklund O, Chapman MJ, Drexel H, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(39):2999–3058. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi Y, Lee S, Kim JY, Lee KE. Current guidelines on the management of dyslipidemia. Korean J Clin Pharm. 2017;27(4):276–283. doi: 10.24304/kjcp.2017.27.4.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters DD, Boekholdt SM. An evidence-based guide to cholesterol-lowering guidelines. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(3):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and recurrent events trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(14):1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease Study Group Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(19):1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, Shear C, Barter P, Fruchart JC, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1425–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundy Scott M., Stone Neil J., Bailey Alison L., Beam Craig, Birtcher Kim K., Blumenthal Roger S., Braun Lynne T., de Ferranti Sarah, Faiella-Tommasino Joseph, Forman Daniel E., Goldberg Ronald, Heidenreich Paul A., Hlatky Mark A., Jones Daniel W., Lloyd-Jones Donald, Lopez-Pajares Nuria, Ndumele Chiadi E., Orringer Carl E., Peralta Carmen A., Saseen Joseph J., Smith Sidney C., Sperling Laurence, Virani Salim S., Yeboah Joseph. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(24):3168–3209. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee of Clinical Practice Guideline of the Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis. 2018 Korean Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia 4th edition (English version). Available from: http://www.lipid.or.kr/bbs/index.html?code=care&category=&gubun=&page=1&number=903&mode=view&keyfield=&key= ().

- 24.Seong SC, Kim YY, Park SK, Khang YH, Kim HC, Park JH, et al. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016640. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, Park JH, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):799–800. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ICD-10 Version: 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en, 2016 ().

- 27.Punekar RS, Fox KM, Paoli CJ, Richhariya A, Cziraky MJ, Gandra SR, et al. Lipid-lowering treatment modifications among patients with hyperlipidemia and a prior cardiovascular event: a US retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(5):869–876. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1292898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK, Daly DD, Jr, DePalma SM, et al. 2016 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of non-statin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(1):92–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naito R, Miyauchi K, Daida H. Racial differences in the cholesterol-lowering effect of statin. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(1):19–25. doi: 10.5551/jat.RV16004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee E, Ryan S, Birmingham B, Zalikowski J, March R, Ambrose H, et al. Rosuvastatin pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics in white and Asian subjects residing in the same environment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(4):330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao JK. Safety and efficacy of statins in Asians. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(3):410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SK. Re-evaluation of efficacy of moderate-intensity statins in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Metab J. 2017;41(1):20–22. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2017.41.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wouters H, Van Dijk L, Geers HC, Winters NA, Van Geffen EC, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Understanding statin non-adherence: knowing which perceptions and experiences matter to different patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fung V, Graetz I, Reed M, Jaffe MG. Patient-reported adherence to statin therapy, barriers to adherence, and perceptions of cardiovascular risk. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0191817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang JY, Jung CH, Lee WJ, Park CY, Kim SR, Yoon KH, et al. Low density lipoprotein cholesterol target goal attainment rate and physician perceptions about target goal achievement in Korean patients with diabetes. Diab Metab J. 2011;35(6):628–636. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.6.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diamantopoulos EJ, Athyros VG, Yfanti GK, Migdalis EN, Elisaf M, Vardas PE, et al. The control of dyslipidemia in outpatient clinics in Greece (OLYMPIC) study. Angiol. 2005;56(6):731–741. doi: 10.1177/000331970505600611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hobbs FD, Southworth H. Achievement of English National Service Framework lipid-lowering goals: pooled data from recent comparative treatment trials of statins at starting doses. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(10):1171–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuiper JG, Sanchez RJ, Houben E, Heintjes EM, Penning-van Beest FJA, Khan I, et al. Use of lipid-modifying therapy and LDL-C goal attainment in a high-cardiovascular-risk population in the Netherlands. Clin Ther. 2017;39(4):819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan BP, Chiang FT, Ambegaonkar B, Brudi P, Horack M, Lautsch D, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol target achievement in patients surviving an acute coronary syndrome in Hong Kong and Taiwan - findings from the dyslipidemia international study II. Int J Cardiol. 2018;265:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.März W, Dippel FW, Theobald K, Gorcyca K, Iorga ŞR, Ansell D. Utilization of lipid-modifying therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high and very-high cardiovascular risk: real-world evidence from Germany. Atheroscler. 2018;268:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breuker C, Clement F, Mura T, Macioce V, Castet-Nicolas A, Audurier Y, et al. Non-achievement of LDL-cholesterol targets in patients with diabetes at very-high cardiovascular risk receiving statin treatment: incidence and risk factors. Int J Cardiol. 2018;268:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hou Q, Yu C, Li S, Li Y, Zhang R, Zheng T, et al. Characteristics of lipid profiles and lipid control in patients with diabetes in a tertiary hospital in Southwest China: an observational study based on electronic medical records. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0945-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, Birou S, Daida H, Dohi S, et al. Executive summary of the Japan atherosclerosis society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Japan – 2012 version. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2013;20(6):517–523. doi: 10.5551/jat.15792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teramoto T, Uno K, Miyoshi I, Khan I, Gorcyca K, Sanchez RJ, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and lipid-modifying therapy prescription patterns in the real world: an analysis of more than 33,000 high cardiovascular risk patients in Japan. Atheroscler. 2016;251:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) was third party data owned by the National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC). Interested researchers can contact NHIC to access the data in the following ways: Tel: 82–33–736-2469 (Big data operation room, NHIC), Web: https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba006cv.do.