Abstract

Background:

Community–academic partnerships play a vital role in ensuring the engagement of African American (AA) men in research. Project Brotherhood (PB) is a community organization that has played an integral role in advancing prostate cancer (PCa) research within two pilot projects supported by the Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative (ChicagoCHEC).

Community Perspective:

It is rare to see community organizations led by AA men acknowledged for their role in advancing health equity research. We provide a community perspective of PB as a model in engaging AA men in research. PB has been recognized nationally by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others demonstrating their national footprint in advancing the inclusion of AA men in all aspects of research. We hope to demonstrate that engagement of AA men in research is important and feasible and to highlight PB as a national model in engaging AA men in research.

Keywords: Black men, community engagement, prostate cancer, community partnerships, community-based participatory research

BACKGROUND OF PB IN COMMUNITY-BASED PARTNERSHIPS IN ChicagoCHEC

The National Cancer Institute (NCI)–funded ChicagoCHEC was established on community engaged principles supporting, fostering and, engaging community partners equitably in research.1 PB, a community-based organization founded on the south side of Chicago to address the multiple health and psychosocial needs of AA men, their families and, social networks. For more than 20 years, PB has been active in community–academic partnerships. As a key community partner for ChicagoCHEC, PB has been a community partner for two incubator pilot projects. One project was a one year pilot research project to examine the increased risk of AA men in developing PCa. Investigators from the University of Illinois at Chicago, the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center-Northwestern University, and Northeastern Illinois University collaborated to better understand biological differences in AA men that may impact PCa risks, by developing modeling systems to study PCa. The research projected aimed to develop a preclinical model to examine PCa in patient samples from Chicago.2

The second project PB is collaborating through ChicagoCHEC is a project aimed at training and engaging a cohort of AA men as citizen scientists to ultimately assess a new biomarker called the Prostate Health Index for PCa screening in AA men.3 The ability to engage the social networks of eight AA men identified, trained, and engaged as citizen scientists is hypothesized to support the identification and recruitment of a cohort of healthy AA men needed to validate the Prostate Health Index as an innovative way to screen for PCa that is more likely to indicate the presence of true disease compared to existing PCa screening with prostate-specific antigen.4

In both projects under ChicagoCHEC, PB has used its expertise as a community partner to identify and engage AA men in research. Traditionally, AA men are considered a hard-to-reach population in clinical and translational research.5 However, the footprint of PB and the adaptation of evidence based theoretical and conceptual frameworks have allowed PB to emerge as an innovate community partner advancing clinical and translational research addressing health inequities in AA men.5 This community perspective highlights the role of PB in two ChicagoCHEC projects and provides a historical overview of PB as a community partner that has collaborated on multiple community–academic partnerships. By sharing the perspective of PB as a community partner we hope to demonstrate how community partners can be “hidden figures” in research that play an integral role advancing health equity research.

HISTORY OF PB IN CHICAGO

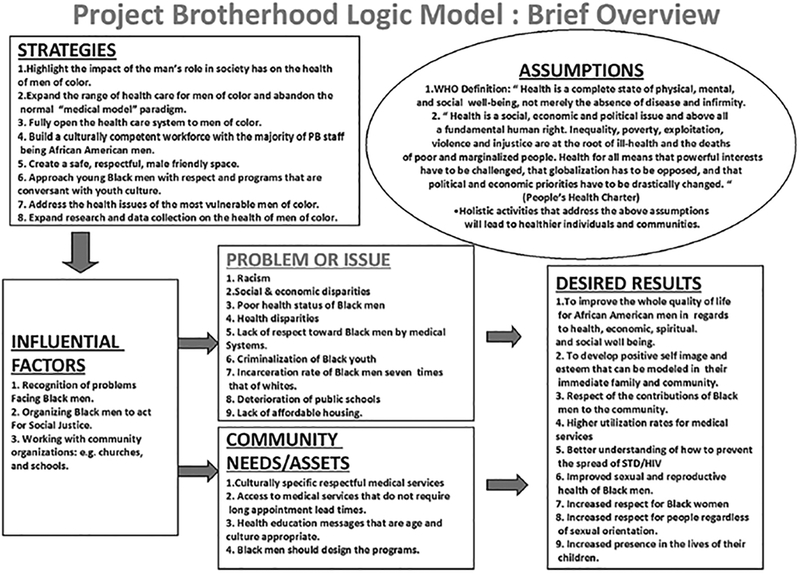

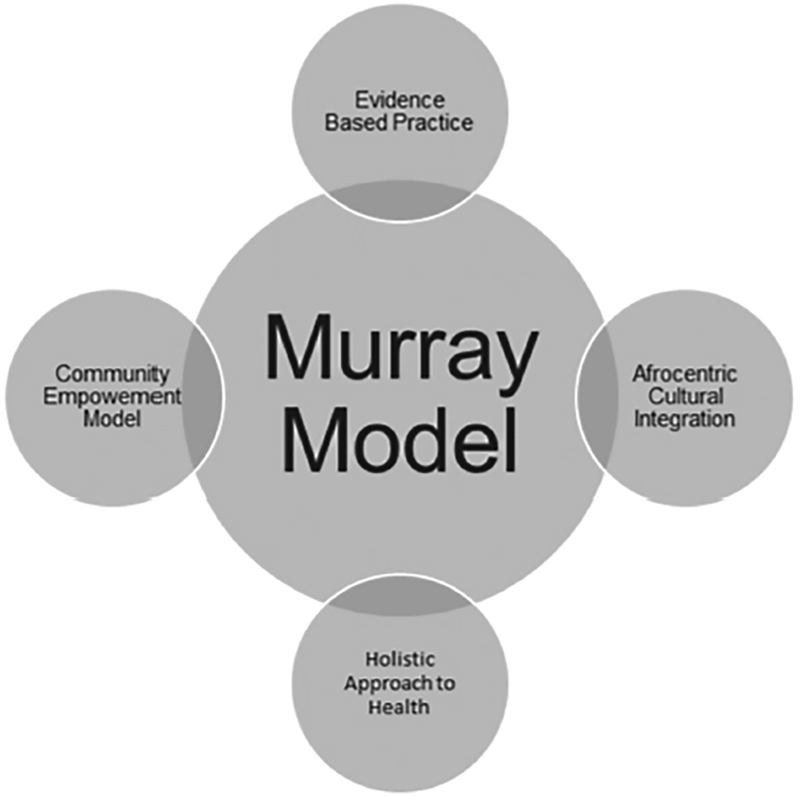

PB had its genesis in November of 1997. PB was birthed out of the need for a holistic place for AA men who received care at the Cook County Health and Hospital System, on the south side of Chicago. PB was built on the adaptation of multiple theoretical frameworks and conceptual models including the health belief model, community empowerment model, elements of community-based participatory research and ideas of “manhood.”6–11 PB was founded on the broad and holistic definition of health by the World Health Organization.12 PB was established under the principle that “healthy” encompasses complete physical, mental, social, economic and spiritual well-being, not merely the absence of disease.12 At its core, PB asserted that health is a fundamental human right and an issue of social justice.13 To achieve its mission, PB sought to create culturally competent and respectful services under the leadership of black men. PB consisted of a multidisciplinary team including nurses, physicians, social workers, administrators, men and women all devoted to ensuring that the multiple determinants of health that converge to impact the health outcomes of AA men were addressed (Figure 1). The logic model for PB has recently been labeled the Murray model after the executive director of PB. The Murray model of engaging AA men in health care research, delivery, and community engagement (Figure 2) deploys evidence based practices for health prevention, screening and treatment for AA men; adapts the community empowerment model to foster equitable engagement of AA men in all aspects of research and care designed to improve health outcomes in AA men and engage them as “partners” in their care and health promotion; integrates culturally Afrocentric practices such as “manhood development” that fosters a sense of pride and familiarity among AA men; and defines health according to the World Health Organization definition as being more than simply the “absence of disease” but focuses on the holistic elements that define health among AA men.6–12 Future community–academic partnerships are underway that will aim to validate and scale the feasibility of implementing the Murray model in research that includes AA men to demonstrate its efficacy in engaging AA men in research.

Figure 1. PB Logic Model. STD/HIV, Sexually Transmitted Diseases/Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

WHO, World Health Organization

Figure 2.

Murray Model of Engaging AA Men in Research, Health Delivery, and Service

Beyond the theoretical framework, PB also realized that “place” and “space” matters and created a “safe” place for AA men to convene, identify their health needs and priorities and to play an integral role in their health outcome. Its primary location is physically housed on the south side of Chicago in the Woodlawn neighborhood, in a community clinic supported by the John S. Stroger Cook County Health System.14

WHO DID WE SERVE AND WHAT DID WE DO?

For over two decades, PB provided health services and public health support to more than 30,000 men and families.14 Services ranged from doctor visits, to job readiness, resume development, decreasing stigma for safe sexual practices including access to free condoms in places were men convene like barber shops and gyms, manhood development classes, fatherhood classes, and an array of other services. In Chicago, PB ushered in a way to leverage traditional places where men convene and share to support the development and dissemination of important health messaging and screening for AA men.

BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS TO ENGAGING AA MEN IN RESEARCH

One of the key reasons why PB has been an integral partner in community-academic partnerships such as those seen in the NCI U54 ChicagoCHEC is based on the fact that PB builds on the assets of AA men while also acknowledging structural and systemic factors that impede the achievement of health in AA men (Table 1). For example, in PCa screening, research and navigation, medical mistrust has been cited as a key factor why AA men are not compliant with PCa screening and treatment recommendations.15,16 This factor further perpetuates the challenge of the inclusion and engagement of AA men in PCa research, which results in research findings that are potentially noninclusive of a myriad of factors that may indicate the lack of generalizability of PCa research findings traditionally conducted among White men.17 Although epigenetics is an emerging field in cancer disparities research, there is a paucity of data that examine factors such as structural violence, food insecurity, stress, racism and social isolation within the continuum of PCa among AA men.16 As a result, the role of PB as a community partner in two ChicagoCHEC pilot projects is an important model in how AA male stakeholders can be engaged in research.

Table 1.

PB Assessment of Barriers and Facilitators to “Health” in AA Men

| Barrier | Facilitator |

|---|---|

| Medical mistrust | Trusted partnerships |

| Lack of access to care | Community-centric care models |

| Eurocentric care models | Culturally tailored care models |

| Lack of AA men as health care providers | Representative clinical staff |

| Monolithic and narrow definition of health | Holistic view of health |

| Systemic racism | Acknowledgement of implicit and explicit biases |

| Health care coverage | Affordable Care Act |

| Socioeconomic factors | Care coordination including social worker support |

| Hypermasculinity | Rites of passage and healthy manhood development |

PB: A NATIONAL LEADER AND RECOMMENDATIONS

PB meets AA men where they traditionally gather and convene. PB has reached thousands of AA men by engaging AA men in barbershops, baseball fields, basketball courts, faith-based and fraternal settings, or just hanging on the corner. Through its understanding that place matters, PB has established itself as a trusted resource of health information and services for AA men on the south side of Chicago. Additionally, PB has also established itself as a national leader and model for community engagement to promote AA men’s health. One of the most noteworthy platforms for PB was when CNN’s Special of Black in America highlighted PB’s efforts.18,19 PB has served on a White House Panel to address human immunodeficiency virus infraction among AA men.20 PB has also been recognized by the CDC for its outstanding work to eradicate health inequities among AA men and it was also mentioned by the CDC as one of the top programs in the country.21 International superstars such as hip hop artist Common have also used their celebrity partnering with PB to promote PCa screening among AA men.

To address the growing gaps in health inequities among AA men related to cancer disparities, PB has been an integral dissemination and engagement partner for two pilot research projects affiliated with the NCI U54 Chicago CHEC. Five perspectives from the field and recommendations to ChicagoCHEC researchers and engagement stakeholders include 1) to be intentionally inclusive of AA men in all aspects of cancer disparities research, from priority research setting, to design, participation, implementation and dissemination; 2) to recognize the need for diversity and inclusion in the biomedical workforce by fostering access to training and exposure of research and engagement opportunities for AA men who are currently underrepresented in medicine that builds on the Murray model of cultural integration and an holistic approach to health; 3) to name and acknowledge racism and structural violence as upstream determinants of health in AA men; 4) to commit to flipping the current model of health care delivery where consumers seek out care to a model that meets men where they convene, play, pray, and work; and 5) to acknowledge the need to develop and implement a holistic approach to the definition of health for AA men that includes the psychosocial well-being along with economic and civic viability. These are values and recommendations that PB has brought to its ChicagoCHEC partners to advance their mission. These values are also scalable to other health inequities beyond cancer that impact AA men.

PB’s reach as a community partner and innovative leader in advancing the public health of AA men extends far beyond Chicago. PB serves as a co-investigator on a Patient-Center Outcomes Research Institute–funded project. This study compared a health behavior intervention, Active & Healthy Brotherhood, with a self-guided control condition to understand the impact of the intervention on health behaviors and health outcomes among AA men. Participants included 333 AA men, age 21 and older, recruited from four communities in North Carolina.22 PB was instrumental in developing the Active & Healthy Brotherhood intervention content, control group health education materials, and developing the participant recruitment materials and strategies. PB was also actively engaged in day-to-day problem solving regarding recruitment and retention of study participants.

CONCLUSIONS

ChicagoCHEC represents a key place and space within cancer health equity research that is committed to fostering authentic community–academic partnerships to advance cancer health equity. Early lessons learned from the participation of PB in two innovative pilot projects that are part of the incubator research process of ChicagoCHEC demonstrate that PB has the capacity to sit at the table as an equitable partner in research and engagement. The more than two decades of successful programing including a presence on national stages like CNN, the CDC, and the White House exemplify the innovative model of PB in addressing health disparities among AA men. Historically, AA men have been marginalized in cancer research and care, further perpetuating the unequal burden of cancer among AA men. PB has been committed to uncoupling the reactions that lead to the perfect storm of cancer disparities among AA men. Engaging AA men in cancer disparities research is not without obstacles and challenges, many of which are rooted in medical mistrust, lack of access to care and lack of engagement of AA men in all aspects of cancer disparities research. However, the early wins of PB engaging academic partners in cancer disparities research demonstrate that not only are community–academic partners feasible in cancer health equity research addressing cancer disparities among AA men, they are also effective in developing and deploying models that are designed to address the unique factors that inform the participation of AA men in cancer research.

REFERENCES

- 1.ChicagoCHEC.org. Mission: Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative [updated 2018; cited 2018 Sept 7]. Available from: https://chicagochec.org/about/mission/

- 2.Available from .org Prostate Cancer Disparity Project: Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative [updated 2018; cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: https://chicagochec.org/research/cores-and-projects/prostate-cancer-disparity/

- 3.Available from .org Citizen scientists: Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative [updated 2018; cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: https://chicagochec.org/research/cores-and-projects/citizen-scientists/

- 4.Loeb S, Catalona WJ. The Prostate Health Index: A new test for the detection of prostate cancer. Ther Adv Urol. 2014. Apr; 6(2):74–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spence CT, Oltmanns TF. Recruitment of African American men: Overcoming challenges for an epidemiological study of personality and health. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2011. Oct;17(4):377–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plowden KO. Using the health belief model in understanding prostate cancer in African American men. ABNF J. 1999. Jan–Feb;10(1):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fawcett SB, Pain-Andrews A, Francisco VT, Schultz JA, Richter KP, Lewis RK, et al. Using empowerment theory in collaborative partnerships for community health and development. Am J Community Psychol. 1995. Oct;23(5):677–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung MW, Irene HY, Meredith M. Community based participatory research: A promising approach for increasing epidemiology’s relevance in the 21st century. Int J Epidemiol. 2004. Jun;33(3):499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen III AJ, Guzman JR. “Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000. May;50(10):1385–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandello JA, Bosson JK. Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychol Men Masculinity. 2013. Sept;14(2):101–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. About WHO: Constitution of WHO: Principles. [updated 2018; cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

- 13.Ravenell JE, Johnson WE Jr, Whitaker EE. African-American men’s perceptions of health: A focus group study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006. Awr;98(4):544–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peyton K South Side Clinic seeks to make Black men feel welcome. Chicago Tribune [updated 2010 Mar; cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2010-03-24/health/ct-x-c-project-brotherhood-20100324_1_black-men-african-american-men-clinic [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones RA, Steeves R, Williams I. How African American men decide whether or not to get prostate cancer screening. Cancer Nurs. 2009. Mar–Apr;32(2):166–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff M, Bates T, Beck B, Young S, Ahmed SM, Maurana C. Cancer prevention in underserved African American communities: Barriers and effective strategies—A review of the literature. WMJ. 2003;102(5):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shenoy D, Packianathan S, Chen AM, Vijayakumar S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? 2016. May 10;16(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CNN. Black in America 2 [press release; updated 2009]. Available from: http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/2009/black.in.america/

- 19.Project Brotherhood: Innovative outreach methods [updated 2012].Available from: https://nchph.org/training-and-technical-assistance/webinars/project-brotherhood-innovative-outreach-methods/

- 20.Greene P, Murray M. Project Brotherhood: Innovative outreach methods [webinar; updated 2010]. The National Council for Health in Public Housing; Available from: http://projectbrotherhood.net/pb-media/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan Ramirez LK, Baker EA, Metzler M. Promoting health equity: A resource to help communities address social determinants of health. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.PCORI. Active and healthy brotherhood. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; [updated c2011–2018; cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: www.pcori.org/research-results/2014/active-and-healthy-brotherhood-program-chronic-disease-self-management-black [Google Scholar]