Summary

Galectin‐3 is the best‐characterized member of galectins, an evolutionary conserved family of galactoside‐binding proteins that play central roles in infection and immunity, regulating inflammation, cell migration and cell apoptosis. Differentially expressed by cells and tissues with immune privilege, they bind not only to host ligands, but also to glycans expressed by pathogens. In this regard, we have previously shown that human galectin‐3 recognizes several genetic lineages of the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, the causal agent of Chagas’ disease or American trypanosomiasis. Herein we describe a molecular mechanism developed by T. cruzi to proteolytically process galectin‐3 that generates a truncated form of the protein lacking its N‐terminal domain – required for protein oligomerization – but still conserves a functional carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD). Such processing relies on specific T. cruzi proteases, including Zn‐metalloproteases and collagenases, and ultimately conveys profound changes in galectin‐3‐dependent effects, as chemical inhibition of parasite proteases allows galectin‐3 to induce parasite death in vitro. Thus, T. cruzi might have established distinct mechanisms to counteract galectin‐3‐mediated immunity and microbicide properties. Interestingly, non‐pathogenic T. rangeli lacked the ability to cleave galectin‐3, suggesting that during evolution two genetically similar organisms have developed different molecular mechanisms that, in the case of T. cruzi, favoured its pathogenicity, highlighting the importance of T. cruzi proteases to avoid immune mechanisms triggered by galectin‐3 upon infection. This study provides the first evidence of a novel strategy developed by T. cruzi to abrogate signalling mechanisms associated with galectin‐3‐dependent innate immunity.

Keywords: Chagas’ disease, galectin‐3, innate immunity, Trypanosoma cruzi

Trypanosoma cruzi expresses proteases that degrade galectin-3, producing a truncated form of the protein that affect its multivalency but not its ability to bind galactose-containing proteins in T. cruzi as a monomer. When such proteases are specifically inhibited with o-phenanthroline and HgCl2, binding of galectin-3 to T. cruzi kills the parasite. Thus, parasitic proteases inactivate the anti-parasite activity of endogenous galectin-3, which could be involved in further progression of chagasic cardiomyopathy.

![]()

Introduction

Trypanosoma cruzi infects humans causing Chagas’ disease, an illness endemic to many Latin American countries 1. It is mainly transmitted by Rhodnius and Triatoma bugs through contaminated faeces, and can also be transmitted by blood transfusions, congenital transplacental, organ transplantation and even orally by ingestion of contaminated food. T. cruzi shares reservoirs and vectors with the related protozoan T. rangeli, which is pathogenic to Reduviid bugs but harmless to humans 2, 3.

Galectins are a multi‐member large family (14 members in mammals) of carbohydrate binding proteins that are highly expressed in immunocompetent tissues and possess a conserved carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) exhibiting broad specificity mainly towards β‐galactosides‐containing glycans 4. Galectins are found in all eukaryotic organisms, including sponges, worms, fungi, insects and mammals 5, 6, 7. Despite this general specificity, subtle structural variations in the CRD result in clearly distinct binding affinities for specific glycans. Among all galectins, galectin‐3 is the only one with a collagen‐like domain attached to the CRD 8, 9, 10, 11. This distinctive collagen‐like domain is rich in Pro‐Gly‐Tyr rich repeating motif, involved in the oligomerization of lectin into higher order oligomers 12, 13. Oligomerization is essential for galectin function, as it causes cross‐linking of surface glycoproteins, leading to the formation of stable associations with its ligands and subsequent signalling and effector functions.

We have recently reported that different members of the human galectin family are able to bind differentially to the distinct life stages of T. cruzi 14 . By using an algorithm on the galectin‐binding profile data set to trypomastigotes and epimastigotes, the different strains tested could be arranged in groups that closely correlated with its genetic lineage or discrete typing units (DTUs), reflecting different galectin ligands presence or exposure that could lead to different DTUs’ distinct biological properties 15, 16, 17, 18. This might imply that the differences in parasite glycome expressed in each DTU could be associated to different clinical outcomes described in Chagas’ disease, such as heart, digestive or neurological pathologies. Indeed, we have reported that the up‐regulation of galectin‐3 in response to the infection acts as a bridge between parasite recognition, host immunity and chagasic cardiomyopathy 19. However, the molecular mechanisms triggered by galectin‐3 upon parasite binding are still unclear. Sato et al. have already reported differential binding of galectin‐3 and ‐9 to Leishmania species 20, 21, but little is known about the ability of galectins to bind to other members of the kinetoplastidae family and the relevance of such interactions.

Here we report that pathogenic T. cruzi not only binds, but also hydrolyses human recombinant galectin‐3. Remarkably, this mechanism prevents galectin‐3‐mediated parasite death, suggesting that T. cruzi may have developed complex strategies to modulate galectin‐3 functions to successfully infect, survive and thrive within its mammalian hosts. In fact, non‐pathogenic T. rangeli binds galectin‐3 but does not modify protein structure. Understanding these novel mechanisms could be essential to lead to better and more selective pathways to target Chagas’ disease.

Materials and methods

Parasites

Epimastigotes (strain Y, DTU II) life forms were continuously cultured in liver infusion tryptose medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 0·01% haemin, as described previously. Cell‐derived trypomastigotes (strain Y, DTU II) forms were from Vero (CCL‐81 cell line obtained from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) cell supernatants after 5 days’ post‐infection. Epimastigotes forms of T. rangeli (strains Choachi and Tre, KP1+ and KP1– respectively) were grown at 28°C in biphasic medium, NNN medium in the solid phase and TC medium as the liquid phase, kindly provided by Dr C. Puerta, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogota, Colombia and Dr MC López López, Instituto de Parasitología y Biomedicina ‘López Neyra’, Granada, Spain 22, 23. Trypomastigotes of T. rangeli were obtained by in‐vitro metacyclogenesis, as described previously 24, 25.

Purification and fluorescent conjugation of recombinant galectins

Expression plasmid for recombinant human galectin‐3 26 was kindly provided by Dr Hakon Leffler (Lund University, Sweden). The preparation and purification of recombinant galectin, as well as purity and activity checking, was performed as described earlier 14, 27, Purified galectins were stored in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) containing 4 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 2 mM β‐mercaptoethanol and 1 mM lactose for long‐term storage. Expression plasmid pQE60 containing the human galectin‐1 sequence was kindly provided by Dr Elena Moiseeva (Leicester Warwick Medical School, Warwick, UK). Recombinant galectin‐1 were purified as described previously 28. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐labelled galectin‐3 was prepared as described earlier 14 and used for immunofluorescence in acetone‐fixed parasites. Briefly, parasites were adhered to Biobond (Telco®) pretreated coverslips and then fixed and permeabilized with cold acetone. Fixed parasites were incubated with FITC‐galectin‐3 (2 μM) at 4°C for 2 h. Unbound galectin‐3 was removed by extensive washing with cold PBS prior to section mounting. Images were acquired using a Confocal LSM510 META microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Galectin cleavage assays

Parasites (107) were incubated with purified recombinant galectins (2 µM final concentration) in 250 µl of serum‐free RPMI medium containing 25 mM Hepes at 37°C with agitation (70g) at indicated times. Parasite‐free supernatants (centrifuged at 3300g, 5 min and filtered) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate‐ polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) and stained by Coomassie blue staining. Some gels were transferred in parallel to nitrocellulose filters, and blotted with specific mouse anti‐galectin‐3 antibody (Leica/Novocastra, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA; clone 9C4) at 2 μg/ml in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS)‐T 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) goat anti‐mouse antibody (Pierce/ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) as secondary antibody that was detected using SuperSignal Developing Reagent (Pierce) using darkroom development techniques for chemiluminescence. To screen for inhibitors of galectin‐3 processing by the parasite, the following protease inhibitors were used: pepstatin A (1, 10 μM), leupeptin (1, 10 μM), aprotinin (0·3, 3 μM), EDTA (1, 10 mM), phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF, 0·1, 1 mM), o‐phenanthroline (OPA, 0·5, 5 mM), bestatin (13, 130 μM), antipain (50, 500 μg/μl), HgCl2 (2, 10 μM), tosyl‐L‐lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK, 2, 50 μM), Tosyl‐L‐phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK, 2, 50 μM) and E‐64 (2, 50 μM).

Phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C treatment

Parasites were treated with phosphatidylinositol‐specific phospholipase C (PI‐PLC) from Bacillus cereus (0·01 U/106 parasites) (Sigma®, St Louis, MO, USA) after PBS washing for 2 h at 37°C to release glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)‐anchored components of the parasite surface. Supernatants and cells were separated by centrifugation, and both fractions were incubated with recombinant human galectins to check cleavage, as described previously.

N‐terminal peptide sequencing and mass spectrometry

Following incubation of recombinant galectin‐3 with T. cruzi parasites, proteins in the supernatant were separated by SDS‐PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Selected proteins as indicated in the text were visualized by staining with 0·5% Ponceau S solution, and N‐terminal sequencing of selected bands were performed on a protein sequencer Procise 494 (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas, Madrid, to perform automated Edman sequencing chemistry. Tryptic digestion of isolated proteins was performed as described previously 14 prior to matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI‐TOF) analysis. MALDI‐TOF was performed using a Bruker Daltonics Autoflex III, at the Proteomic Service, Centro de Biología Molecular ‘Severo Ochoa’ as described 14. Briefly, SDS‐gel electrophoresis was performed as before in low percentage bisacrylamide gels that were stained in a MS compatible Coomasie stain. Selected bands were excised immediately after electrophoresis and placed in 0·6‐ml tubes and destained and electroeluted using the Proteo‐PLUS system, dialyzed overnight and concentrated before co‐crystallization with the MALDI‐matrix, as described previously 29.

Parasite viability assays

To check the ability of galectin‐3 to induce parasite death, 2 × 106 parasites were exposed to recombinant galectin‐3 (2–40 µM) in the presence or absence of OPA (5 mM) for 10 min in PBS: RPMI (1 : 1 ratio) followed by incubation in 2 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI) for 5 min (Sigma) in PBS at 4°C in the dark. PI uptake was assessed by flow cytometry analysis on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur using CellQuest software and data were analysed using the FlowJo® software (TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Results

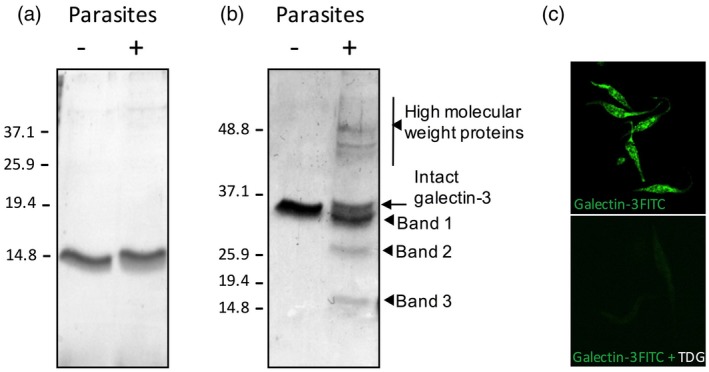

Our previous work with galectins and T. cruzi showed that galectins recognize different life stages of the parasite 14, 19. To test whether T. cruzi interaction with galectins modifies their structural integrity, purified recombinant human galectins with both pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory actions, such as galectin‐1 and ‐3, were incubated with live T. cruzi epimastigotes at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the parasites were removed by centrifugation and supernatants were filtered. Contents were then analysed by SDS‐PAGE (Fig. 1a,b). When incubated with live parasites, no change was detected with galectin‐1 (Fig. 1a) but, surprisingly, a significant reduction in intensity of galectin‐3 (37 kDa) was observed. In parallel, three major bands of smaller molecular weight (Fig. 1b): band 1 (~35 kDa), band 2 (~25 kDa) and band 3 (~15 kDa) were observed upon incubation with the parasite, in addition to some other proteins of higher molecular weight. MALDI‐TOF analysis of the galectin‐3 samples exposed to parasites identified proteins of parasite origin, such as β‐tubulin (49·5 kDa), α‐tubulin (46·9 kDa) and elongation factor 1 alpha (44·6 kDa), suggesting that the proteins above 37 kDa observed in the gels upon incubation of galectin‐3 with T. cruzi are of parasitic origin. In line with previous observations, galectin‐3 bound to lactose‐containing glycoconjugates in the parasite (Fig. 1c), indicating that binding of galectin‐3 to T. cruzi is dependent upon the CRD. Therefore, we hypothesized that bands 1, 2 and 3 seen in the gels (Fig. 1b) were truncated forms of galectin‐3 following interaction with the parasite.

Figure 1.

Effects of Trypanosoma cruzi on galectin‐1 and ‐3 in vitro. Recombinant human galectin‐1 (a) or galectin‐3 (b) (2 μg) were incubated with T. cruzi at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant filtered before analysis with sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining. Proteins observed as result of galectin‐3 and parasite interaction are indicated by arrows. Three proteins of lower molecular weight are designated as bands 1, 2 and 3, as shown. (c) Parasites were fixed with acetone and stained with recombinant galectin‐3–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) in the presence or absence of thiodigalactoside (TGD, 10 mM) prior to image acquisition in a confocal microscope.

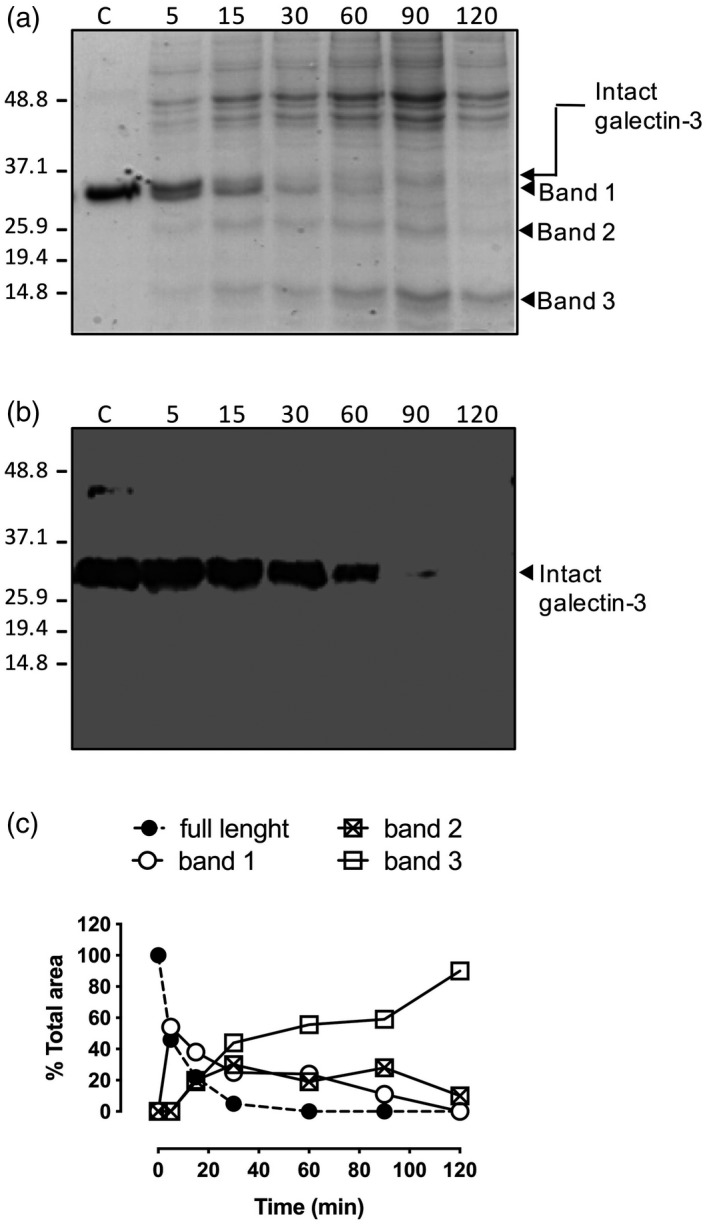

To test this hypothesis, an in‐vitro time–course revealed that under our experimental conditions intact galectin‐3 is completely removed from the medium in ~2 h, when only bands 1–3 were present in the cell culture (Fig. 2a). Samples were subjected to immunoblotting using a monoclonal antibody against galectin‐3 (Fig. 2b), confirming that intact galectin‐3 was gradually removed when incubated with T. cruzi, providing further support to our hypothesis, as generation of truncated galectin‐3 forms will appear with the disappearance of intact galectin‐3, recognized by the monoclonal antibody in Fig. 2b. Furthermore, this ruled out that proteins of higher molecular weight were galectin‐3 oligomers, although it still did not identify the nature of the smaller proteins named bands 1, 2 and 3. Band densitometry of the Coomassie blue‐stained gel allowed the description of the kinetics of appearance/degradation of these bands (Fig. 2c). The possibility that the specific cleavage was produced by contaminant proteases in the media was ruled out because no shorter bands were found when galectins were incubated with fresh complete medium for up to 4 h either at 28°C or 37°C.

Figure 2.

Time course of galectin‐3 processing by Trypanosoma cruzi. Galectin‐3 (2 μM) was incubated with parasites for given times and parasite‐free supernatants were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) followed by Coomassie blue staining, showing the appearing bands of lower molecular weight, indicated by arrows (bands 1, 2 and 3) (a). Western blot analysis of the proteins found in the supernatant after incubation of galectin‐3 with T. cruzi epimastigotes. Supernatants were run on gradient gels under denaturing conditions. After transfer to nitrocellulose the blotted bands were immunodetected with a specific mouse anti‐human galectin‐3 monoclonal antibody and subsequently visualized with peroxidase‐labelled goat anti‐mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies (b). Integrated intensities of intact galectin‐3 and the bands of lower molecular weight (bands 1, 2 and 3) were obtained by densitometric analysis of Coomassie blue staining SDS‐PAGE gel and expressed as percentage of total expression (c).

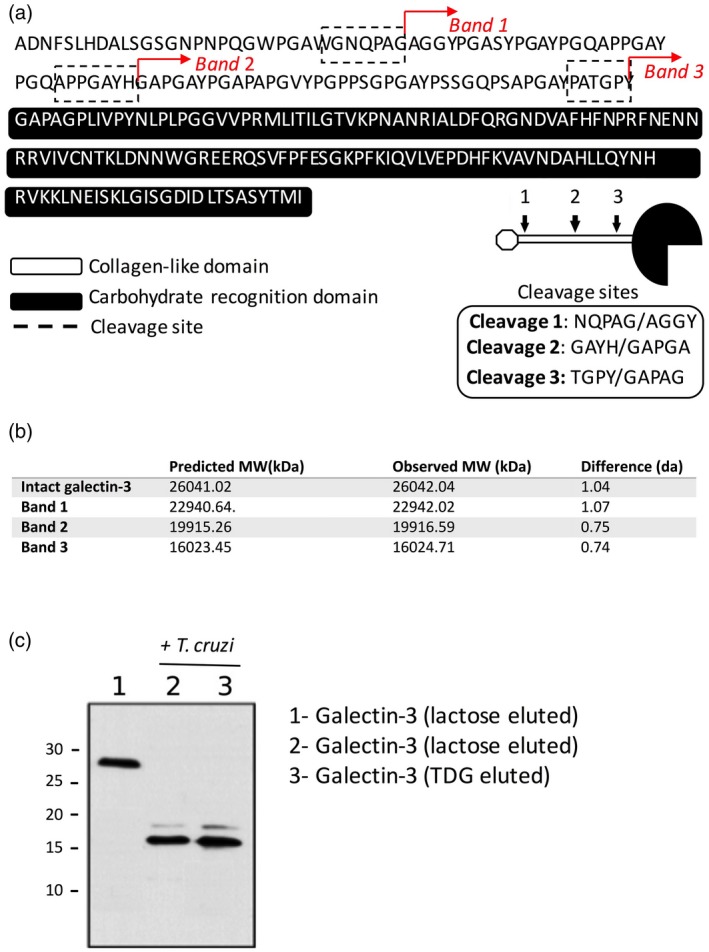

T. cruzi processes galectin‐3 and releases an intact and functional CRD

To confirm our hypothesis that the fragments observed in the SDS‐PAGE gels following exposure of parasites to galectin‐3 were truncated forms of the carbohydrate binding protein, bands 1, 2 and 3 were excided from SDS‐PAGE gels, isolated and subjected to N‐terminal peptide sequencing and MALDI‐TOF analysis of trypsin digestions of these fragments. N‐terminal sequencing of bands 1–3 revealed internal galectin‐3 sequences in the three cases, indicating that these proteins were indeed truncated versions of galectin‐3. Specifically, the N‐terminal sequences obtained were: band 1: AGGYPGASYPG, band 2: GAPGAYPGAP and band 3: GAPAGPLIVP, all within the galectin‐3 sequence (Fig. 3a), indicating that distinct cleavages take place between amino acids G32A33, H64G65 and Y107G108, respectively, all on the N‐terminal collagen‐like domain, out of the CRD (full sequence in Fig. 3a). To further corroborate this, MALDI‐TOF analysis after incubation of galectin‐3 with T. cruzi revealed three major products with molecular masses of 22942.02, 199156.59 and 16024.71 that matched with the predicted values based on the N‐terminal sequencing data (Fig. 3b). These would correlate with the observed bands 1, 2 and 3, although they appear to be bigger proteins when compared with the protein ladder of molecular weight standards. This is probably due to specific protein conformations and interactions that might make galectin‐3 migrate less through the SDS‐PAGE gel. The nature of these bands was confirmed by MALDI‐TOF analysis of the fragments resulting from tryptic digestion of bands 1–3, as the results matched exactly the predicted peptides based on the N‐terminal sequencing data (Supporting information, Fig. S1). Therefore, these findings showed a sequence‐dependent galectin‐3 processing by T. cruzi, suggesting that at least two proteases could be involved in the process, one targeting the sequence (H/Y)GAP and a second targeting AGGY.

Figure 3.

Cleavage sites of galectin‐3 are within the N‐terminal domain. Bands 1, 2 and 3 as referred to previously were isolated and subjected to N‐terminal protein sequencing. Cleavage sites of bands 1, 2, and 3 corresponded to internal sequences of the galectin‐3 protein and are indicated in the peptide sequence shown. Sequences obtained by N‐terminal protein sequencing are underlined. Diagram shows the cleavages sites on a schematic representation of galectin‐3. (a) Bands 1–3 were isolated and matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI‐TOF) analysis was conducted to evaluate their molecular weight. Values were compared with the predicted molecular weight based on the galectin‐3 sequence and the N‐terminal sequencing data for each protein (b). Intact galectin‐3 was exposed for 2 h to live parasites, when media were collected, filtered and applied to a lactose‐sepharose column. The column was extensively washed to remove unbound material and eluted with lactose (100 mM) or thiodigalactoside (10 mM). The eluted fraction was further subjected to SDS‐PAGE and stained with Coomasie blue to detect proteins (c).

Interestingly, degradation of galectin‐3 by T. cruzi occurred exclusively within the N‐terminal domain of the protein, whereas the CRD domain responsible for the protein binding to galactose‐containing glycans remained intact and potentially functional, suggesting that T. cruzi proteases could modulate galectin‐3 actions, rather than suppress them. To confirm this, we decided to evaluate whether the truncated galectin‐3 (as observed in band 3 in Figs 1b, 2a) still had a functional CRD. Thus, intact galectin‐3 and cleaved galectin‐3 resulting from long incubation with parasites (4 h) were applied to a lactose‐sepharose affinity column. In all cases, galectin‐3 and its truncated form corresponding to the CRD (band 3) were retained in the column and subsequently eluted with the competing carbohydrates lactose and thiodigalactoside (Fig. 3c), indicating that processing by T. cruzi did not affect the CRD ability to bind galactoside‐containing carbohydrates. Nevertheless, galectin‐3‐mediated effects could still be severely affected, as the N‐terminal domain is responsible for protein oligomerization and regulation of various innate immune functions of galectin‐3.

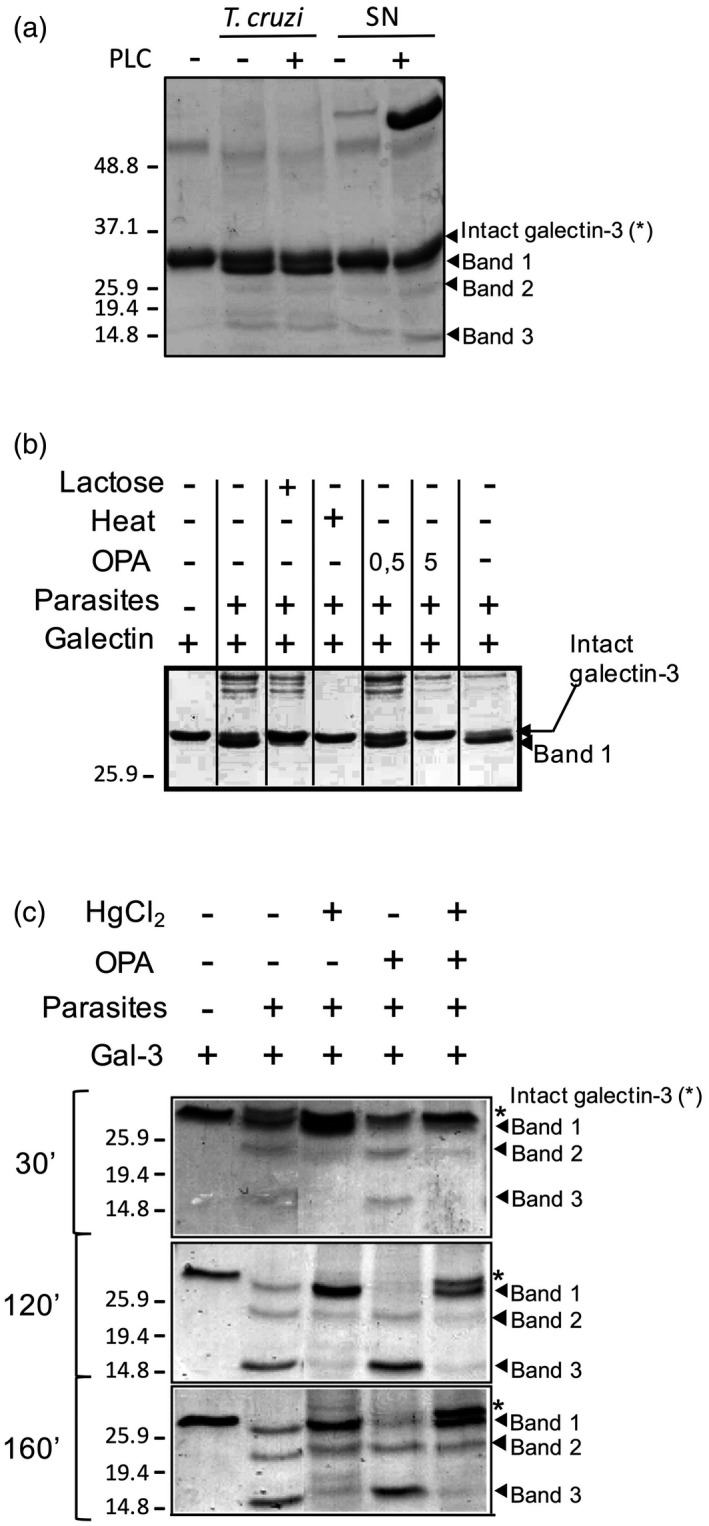

Hydrolytic processing of human galectin‐3 by T. cruzi involves multiple proteases inhibited by OPA and mercuric chloride

The identification of the precise amino acid sequences targeted by T. cruzi in galectin‐3 provided initial data on the nature of potential protozoan proteases involved. To evaluate whether the protease(s) responsible for galectin cleavage were secreted in the extracellular medium, parasites were cultured in vitro and conditioned media were collected and then tested for its ability to process galectin‐3 (Fig. 4a). In addition, parasites were treated with PI‐PLC enzyme that releases GPI‐anchored proteins from the membrane, to test whether the protease(s) were anchored to the parasite membrane by GPI. This is particularly important for T. cruzi, as GPI‐anchored proteins are expressed at all developmental stages and encoded by thousands of members of multi‐gene families, such as trans‐sialidases, mucins and metalloproteinase gp63. In fact, it has been estimated that up to 12% of T. cruzi genes possibly encode GPI‐anchored proteins 30. PI‐PLC‐treated and untreated parasites and the resulting supernatants were incubated with recombinant galectin‐3 and the digestion products of recombinant galectins were submitted to SDS‐PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 4a). Results show that galectin processing is due to at least two different proteases. One, responsible for the cleavage at the sequence AGGY, is not secreted or anchored through GPI, as band 1 is not seen with secreted parasite material. The protease specific for the GAP sequence was secreted, as supernatant from cultured parasites induced the appearance of bands 2 and 3.

Figure 4.

The cleavage of galectin‐3 by Trypanosoma cruzi depends on at least two families of proteases. (a) T. cruzi epimastigotes were treated with phosphatidylinositol‐specific phospholipase C (PI‐PLC) to release glycosylphosphatidylinisotol (GPI)‐anchored proteins to the medium, and galectin‐3 (2 μM) was incubated for 15 min at 37°C with parasites or released supernatants (SN). (b) Galectin‐3 proteolisis by parasites (15 min, 37°C) was conducted in the presence of ortho‐phenanthroline (0·5 and 5 mM), lactose (100 mM) and after heat inactivation of parasites. (c) Galectin‐3 (2 μM) was incubated with parasites at given times (30, 120 and 160 min at 37°C) with OPA, mercuric chloride or the two compounds at the same time. In all cases (a–c), the cleavage of galectin‐3 was analysed by Coomassie blue staining.

Next, we repeated the proteolytic experiments in the presence of a large battery of specific protease inhibitors, as listed in Materials and methods. Of all the inhibitors tested, only OPA – a specific inhibitor for zinc metalloproteases – displayed some inhibitory effect on galectin‐3 processing (Fig. 4b), blocking the cleavage at site 1 (sequence AGGY, band 1). Furthermore, lactose and parasite heat inactivation also prevent galectin‐3 processing, suggesting that this T. cruzi metalloprotease requires active binding of galectin‐3 to the parasite (Fig. 4b). Next, as the remaining cleavages within galectin‐3 took place only in the N‐terminal domain, which is a collagen‐like domain, we hypothesized that the second protease would be a T. cruzi collagenase. Thus, a set of collagenase inhibitors were tested, including TLCK, TPCK and mercuric chloride, which have been reported to inhibit collagenase‐like enzymes already described in T. cruzi 31. Only mercuric chloride inhibited the cleavage in the sequence GAP, bands 2 and 3 (Fig. 4c), suggesting a role of the described T. cruzi collagenase in the galectin‐3 cleavage. Interestingly, the combination of mercuric chloride and OPA preserved intact galectin‐3 in the medium even after 160 min of incubation, whereas all galectin‐3 was somehow processed in the absence of inhibitors (Fig. 4c). Further investigation is needed to determine whether or not the observed cleavages are sequential, although it is likely that both proteases follow different kinetics in their mechanism of action and could act independently.

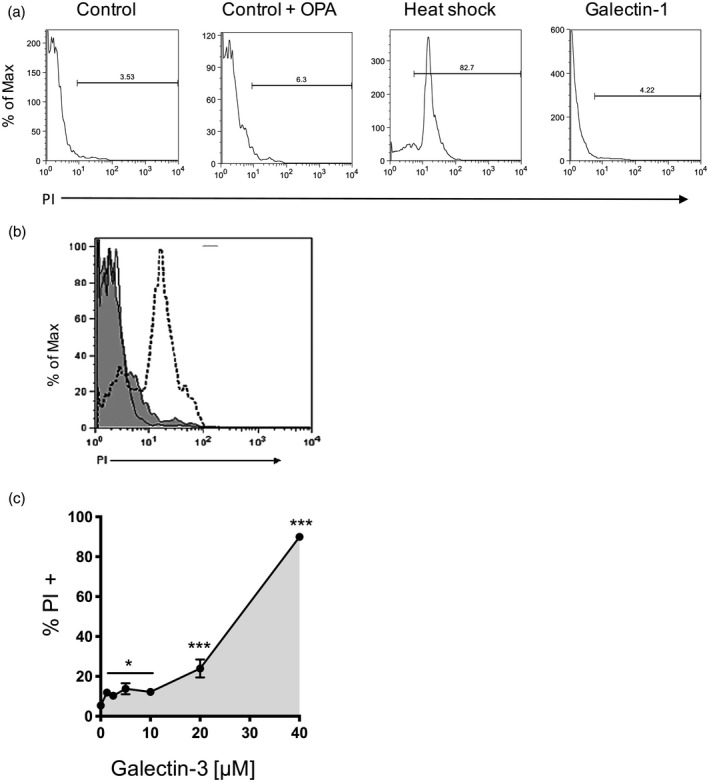

Blocking galectin‐3 proteolysis leads to galectin‐induced parasite death

Host–parasite co‐evolution increased selective pressure on T. cruzi to develop molecules able to modulate the immune response to the infection. Herein, we identify and describe a novel mechanism triggered by T. cruzi to cleave the N‐terminal collagen‐like domain of galectin‐3 which, in turn, may affect many of its biological actions that rely upon the N‐terminal domain oligomerization. The question now is: what is the functional effect underlying N‐terminal degradation of galectin‐3 by T. cruzi? As galectin‐3 has been shown to directly induce death of other pathogens, such as Candida sp. 32, we hypothesized that longer interactions of intact full‐length galectin‐3 would result in parasite death. To test this hypothesis, parasites were incubated with galectin‐3 in the presence of OPA to inhibit and delay galectin‐3 processing, and then stained with PI to check parasite viability (Fig. 5). OPA did not increase PI staining on parasites at the concentration used (5 mM) (Fig. 5a), ruling out a potential toxic effect of the protease inhibitor. The positive PI staining of parasites when OPA and galectin‐3, but not galectin‐3 alone, were present, indicating that intact galectin‐3 induced parasite death (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, when parasites were incubated with galectin‐1 at 10 μM we did not observe any effect on parasite viability (Fig. 5b), while galectin‐3 showed significant effects above 2 μM. Thus, galectin‐3‐mediated parasite killing was shown to be dose‐dependent (Fig. 5c), perhaps reflecting the multivalency of galectin‐3 upon binding to parasite glycoconjugates.

Figure 5.

Parasites undergo cell death when they are incubated with galectin‐3 in the presence of ortho‐phenanthroline (OPA). Cell viability of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes was evaluated by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry. Parasites were incubated (15 min, 37°C) with and without OPA (5 mM), galectin‐1 (2 μM) and parasites killed by heat shock were used as a positive control (90°C, 10 min) for PI staining (a). Neither parasites alone nor OPA‐treated parasites showed a significant increase in PI staining. Galectin‐3 led to parasite killing when it was combined with OPA (5 mM, histogram, dotted line) compared to galectin‐3 without inhibitor (histogram, straight line) or OPA alone (filled grey histogram) (b). Parasites were incubated with increasing concentrations of galectin‐3 in the presence of OPA 5 mM and stained with PI to check cell viability as before. Results show the mean of three independent experiments showing mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). ***P < 0·001, *P < 0·05 compared to non‐treated controls (no galectin‐3, 5 mM OPA) (c).

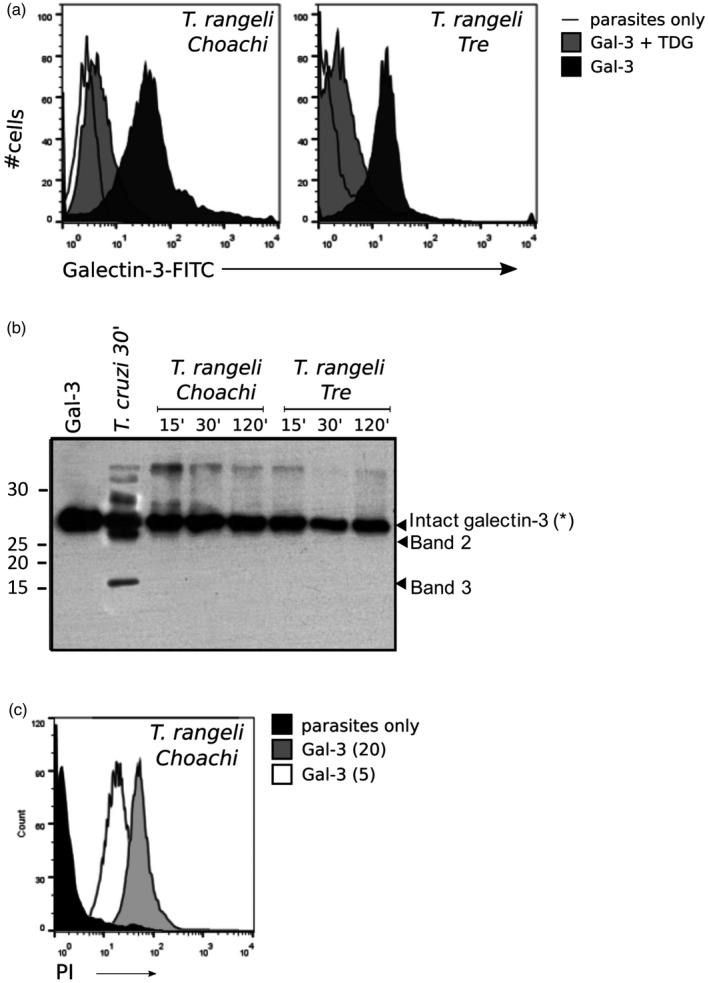

Galectin‐3 recognition and processing by a non‐pathogenic‐related parasite, T. rangeli

Next, to address whether binding and processing of human galectin‐3 was specific for T. cruzi, we studied whether the non‐pathogenic‐related parasite T. rangeli showed similar mechanisms to process the carbohydrate binding protein. Towards this goal, we first investigated the potential of T. rangeli to bind FITC–galectin‐3 by setting up a flow cytometry assay, as described previously for T. cruzi 10. As shown in Fig. 6a, galectin‐3 bound to two strains (Choachi and Tre) of the non‐pathogenic parasite, albeit with lower affinity than T. cruzi 14. Similar to what happens with T. cruzi, the binding is dependent upon the active CRD, as thiodigalactose blocks the binding (Fig. 6a). Once we demonstrated that T. rangeli‐exposed glycans could be recognized and bound by recombinant human galectin‐3, we tested whether or not the non‐pathogenic parasite shares the ability to cleave galectin‐3. Thus, T. rangeli trypomastigotes were incubated with recombinant human galectin‐3 during different periods. Moreover, we used T. cruzi trypomastigotes to confirm that infective forms of the parasite life cycle also induce cleavage of galectin‐3 (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, and contrary to what happens with T. cruzi, we were not able to detect any truncated forms of galectin‐3 when the protein was incubated with T. rangeli, even at incubation times longer than 2 h (Fig. 6b). This suggests that non‐pathogenic T. rangeli is not equipped with homologous proteases expressed by the pathogenic T. cruzi. A further question to be determined was whether galectin‐3 induces T. rangeli death, as this protozoan lacks the molecular machinery to process galectin‐3. We set up a similar assay as described previously (in the absence of protease inhibitors), which confirmed the ability of galectin‐3 to kill T. rangeli in vitro (Fig. 6c), probably by similar mechanisms triggered in T. cruzi when parasite Zn‐metalloproteases and collagenase‐like enzymes are inhibited.

Figure 6.

Galectin‐3 binds non‐pathogenic Trypanosoma rangeli without processing it, resulting in protozoan death. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐labelled recombinant galectin‐3 was incubated with T. rangeli trypomastigotes Choachi (KP1+) and Tre (KP1–) strains at 4°C and galectin binding was quantified by flow cytometry (black histograms) compared to non‐stained cells (straight line) (a), and thiodigalactoside was used (10 mM) to inhibit galectin‐3 binding (grey histogram). Galectin‐3 (2 μg) was incubated with cell‐derived live trypomastigotes of T. cruzi, or in‐vitro differentiated trypomastigotes of T. rangeli at 37°C for 120 min. After incubation, the mixtures were centrifuged and the supernatants filtered, applied to lactose–sepharose, as described previously, analysed by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining (b). In‐vitro differentiated trypomastigotes of T. rangeli Choachi were incubated with full‐length galectin‐3 for 10 min at 37°C (white histograms, 5 mM, grey histograms, 20 mM), and then stained with propidium iodide (PI) as described previously to evaluate cell viability compared to non‐treated controls (black histograms) (c).

Prediction of potential T. cruzi proteases processing galectin‐3

Identification of specific T. cruzi proteases involved in galectin‐3 processing could not only provide further insight into the complex immunosuppressive mechanisms triggered during infection, but also offer novel therapeutic opportunities to target Chagas’ disease. Although further work needs to be conducted, we undertook an initial bioinformatic approach to define some candidates. Using galectin‐3 sequence (GeneBank Accession no.: BAA22164.1), we used the bioinformatics tool PROSPER 33 to identify proteases with the ability to generate galectin‐3 fragments of approximately 16 and 23 kDa. This search found retropepsin (A02.001), cathepsin K (C01.036), metallopeptidase‐9 (M10.004), metallopeptidase‐3, elastase‐2 (S01.131) and cathepsin G (S01.133). Then, homologous proteases with the predicted activities were identified by Blastp against the complete T. cruzi Y strain genome 34 (e‐value ≥ 1e‐5 and identity ≥ 50%) and the complete proteome of T. rangeli (proteome ID: UP000031737). Homologues in both species were collapsed and filtered by CD‐HIT 35 and custom python scripts (similitude ≥ 50%). Among all proteases, we ruled out proteases present in both T. cruzi and T. rangeli. Our analysis identified five proteins that are present exclusively in T. cruzi and have the potential of processing galectin‐3 at the observed positions: (i) metallo‐beta‐lactamase (EKG05779.1), (ii) CAAX prenyl protease 1 (EKG03313.1), (iii) zinc carboxypeptidase (EKG03764.1), (iv) metallopeptidase (PWU92748.1) and (v) aminopeptidase (ESS61840.1). Protein sequences for these proteases are shown in Supporting information, Fig. S2. These results therefore identify proteases that are unique to T. cruzi and absent in the non‐pathogenic T. rangeli, supporting the hypothesis that galectin‐3 degradation might be a highly specialized mechanism associated with parasitic trypanosomatids.

Discussion

Diverse strategies have arisen during millennia of host–parasite co‐evolution to define infection and immune responses in the host. Regarding galectin and T. cruzi, we have described that human galectin‐3 recognizes the parasite through binding to several surface glycoproteins 14, highlighting the role of parasite glycoconjugates to interact with mammalian cells. In this study we report that the association of galectin‐3 with T. cruzi also affects protein integrity resulting in the formation of truncated forms of the protein, which contains an intact CRD but lacks the N‐terminal collagen‐like domain, rendering galectin‐3 unable to oligomerize. Three cleavage sites within the N‐terminal domain were identified. The proteases implicated in galectin‐3 cleavage were defined as Zn‐metalloproteases and a collagenase, although other proteases could be involved. In a systematic screening of diverse protease family’s inhibitors, only the Zn‐metalloprotease inhibitor OPA and HgCl2 inhibited T. cruzi‐mediated galectin‐3 processing, confirming the notion of at least two kinds of protease involved. It has already been reported that HgCl2 inhibits a T. cruzi collagenase 31, perhaps responsible of some cleavage observed in galectin‐3, as the N‐terminal domain of galectin‐3 shares a high degree of homology with collagen. Among other parasite proteases described, cruzipain is the more abundant protease described in T. cruzi so far 36, but it is not implicated in galectin‐3 processing, as its specific inhibitor (E64) was unable to abrogate galectin‐3 cleavage. Bioinformatic analysis of proteases in T. cruzi versus the non‐pathogenic T. rangeli suggests that at least five proteins could be involved in this process, although experimental validation of these data is still required.

Whatever the protease(s) involved might be, degradation of galectin‐3 N‐terminal domain could dysregulate the host innate immune responses that depend upon galectin‐3 oligomerization, e.g. lateral receptor mobility such as T cell receptor (TCR) on T cells 37 or polarization of T helper type 1 (Th1) responses 38. T. cruzi could also modulate galectin‐3 function if intracellular amastigotes are able to process intracellular galectin‐3, as it is known that the pleiotrophic effects of galectins depend upon their subcellular location. Indeed, the first cleavage would remove the phosphorylation site responsible for protein translocation from nucleus to cytosol. Other proteases implicated in galectin‐3 processing have already been reported in the host, such as matrix metalloproteases 2 and 9 39, 40, 41, or by pathogens such as Leishmania major 20, showing how galectin‐3 function can be regulated by proteolytic digestion to control endogenous functions or pathogen invasion and infection. Similarly, it has been recently described that galectin‐3 is a target for proteases involved in the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus 42. However, no collagenases had been reported to be involved in galectin‐3 proteolysis, and the role of these mechanisms in T. cruzi infection had not yet been described.

During Chagas’ disease, T. cruzi must evade complex defensive systems that are present in the host. Glycoconjugates are major targets of different innate defensive systems, such as collectins, defensins, dectins or anti‐glycans antibodies, that are inducers of microbial clearance 43. Sera of patients with chronic Chagas’ disease contain elevated levels of anti‐α‐galactosyl antibodies that are lytic to T. cruzi 44, 45, being the smallest immunogenic epitope Galα1‐3Galβ1‐4GlcNAcol, isolated from a mucin‐like protein from T. cruzi termed F2/3 46, 47. Perhaps galectin‐3 binds to this mucin‐like protein, exerting a similar effect over T. cruzi to that produced by lytic anti‐gal antibodies. Moreover, it is known that galectin‐3 is quickly released from cells after T. cruzi interaction as part of the innate immune response 48, 49, 50 and truncated galectin‐3 might provide some advantages for the parasite, such as masking of galactosyl epitopes or promotion of cell adhesion.

Our results show that galectin‐3 induces direct parasite killing when specific proteases are inhibited, suggesting that cross‐linking of crucial glycoconjugates of T. cruzi can induce parasite death. Supporting this, a vegetal lectin, Euonymus europaeus agglutinin (EEA), with related binding affinity to galectins and anti‐gal lytic antibodies, can induce T. cruzi killing 51, possibly suggesting that anti‐gal antibody, galectins and EEA are targeting similar receptors. The F2 fraction recognized by most of the anti‐gal antibodies corresponds mainly to a 74 kDa mucin‐like protein 51, and this is close to the molecular weight of the major T. cruzi ligand of all the galectins tested 14. This F2 fraction could be the galectin ligand on T. cruzi surface responsible for galectin‐mediated death, but further work must be conducted to confirm this.

Galectin‐3 can induce death of Candida albicans 32, in agreement with the hypothesis that galectins could directly kill some pathogens. This is the only reference of galectins acting as direct microbicide agents, and our data are the first demonstration, to our knowledge, of a pathogen mechanism able to prevent this action. We also attempted to block the collagenase‐like protease to conduct similar experiments to those performed with OPA, but HgCl2 became toxic to some degree for the parasite at longer times, increasing the uptake of PI. We would expect a more potent microbicide effect of galectin‐3 if we were able to block both proteases simultaneously, possibly reducing the effective concentration of galectin‐3 to induce killing of the parasite. Such effective concentration is likely to be similar to physiological levels of galectin‐3 observed in inflammatory microenvironments. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that intracellular concentrations of galectin‐3 can reach very high levels, up to 5 μM 52, which would have microbicide effects on intracellular parasite forms. Similarly, local concentration of galectin‐3 on the parasite membrane could go beyond this value upon binding to T. cruzi glycoconjugates, a process that is known to increase local galectin‐3 concentration to form dimers 27, as galectin‐3 remains as single monomers up to 100 μM in solution.

Moreover, identification of the proteases implicated in galectin processing might represent a promising candidate in the search for molecular targets seeking effective chemotherapeutic agents to treat Chagas’ disease. We cannot rule out that other galectins could induce parasite death; for example, the monomeric galectin‐1 at higher concentrations. However, this galectin does not act as a microbicide at concentrations where intact galectin‐3 does, suggesting a more specialized role for the latter protein in innate immunity against T. cruzi.

Galectin‐3 processing seems to require more time than the passive interaction of parasite‐galectins. Therefore, a sequential interaction process between galectin‐3 and T. cruzi could be postulated, in which the parasite first interacts with intact galectin, promoting parasite adhesion to host cells supporting infection. Once the parasite is attached to the cell membrane, it would initiate cell penetration and possibly galectin processing, thus preventing the microbicide action. However, this scenario may be more complex in vivo due to the variable galectin‐3 affinity for glycans in distinct cell types, competition between host and parasite glycans for galectin‐3 binding, the presence of other galectins or even the existence of parasite carbohydrate‐binding proteins that could compete with host galectins over both parasite and endogenous host ligands. Nevertheless, here we show that a pathogenic parasite such as T. cruzi has developed as part of the successful survival strategy by a mechanism which can abolish the inherent nature of galectins as part of the innate immune system, their multivalency and microbicidal activities.

To confirm the galectin cleavage as a pathogenic property, we tested the ability of the closely related protozoa non‐pathogenic T. rangeli. T. rangeli shares an ecological niche with T. cruzi, infecting the same hosts but not being pathogenic for humans 53, even when they can be found in mixed infections both in mammals and insect vectors 53, 54. The genome of T. rangeli has been recently described 55, and some differential characteristics compared to T. cruzi have emerged. T. rangeli contains fewer copies of putative galectin ligands 14 that cover the parasite surface 56 such as mucins and mucin‐associated surface proteins (MASPs), approximately 2500 copies in T. cruzi Cl‐Brener versus 65 in T. rangeli 55, coherent with transcriptomic 57 and proteomic data 25. It has recently been reported that virulent and non‐virulent strains of T. cruzi exhibit different transcriptomes 58. T. rangeli contains a lower number of genes for proteinases such as cysteine protease, metallopeptidases and, presumably, other proteases. The poor ability of T. rangeli to sustain an infective cycle (invade and multiply) in the mammalian host could be related to the low abundance of those gene groups that could act in concert during the T. cruzi infection. There have been reports from our group and others 14, 48, 49, 59, 60 involving galectin‐3 in the adhesion, binding and posterior infection to host cells by T. cruzi. Similar mechanisms could be used by T. rangeli, with less success due to low avidity binding to lower number of ligands exposed on the surface. Once galectins promote and consolidate parasite adhesion and binding to host cells, a second event might occur: the inactivation of galectin oligomerization by proteolytic cleavage [while the parasite is in contact with the membrane, as the protease(s) are not secreted].

Could T. cruzi develop a biological mechanism to utilize galectin‐3 to infect cells, while blocking subsequent danger signals associated to the multivalency and oligomerization capacity of galectins? This idea prompts the evaluation of different T. cruzi lineages exhibiting different virulences, and even tissue trophisms differ in their ability to proteolytically process galectin‐3 controlling differentially tissue‐specific networks of immune regulation.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

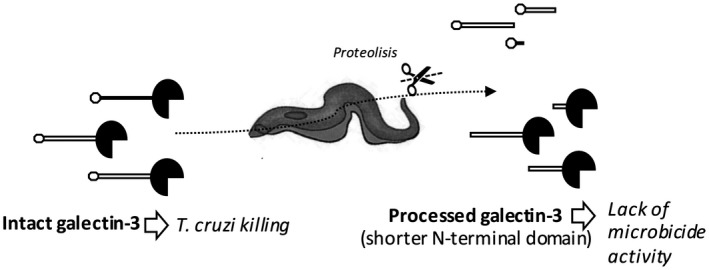

Figure 7.

Proposed model utilized by Trypanosoma cruzi to escape the microbiocide action of galectin‐3.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. MALDI‐TOF data of selected bands subjected to triptic digestion. Bands 1, 2 and 3 as indicated in figure 1B were isolated from SDS‐PAGE gels after Coomasie Blue Staining and proteins were destained and electroeluted using Proteo‐PLUS system, dialyzed overnight and subjected to trypsin digestion. Resulting peptides were analysed by MALDI‐TOF using a Bruker‐Daltonics Autoflex III. Predicted sequences based on the N‐terminal sequencing data, and predicted and observed molecular weight of triptic peptides are shown for each protein, bands 1, 2 and 3.

Fig. S2. Protein sequences of T. cruzi proteases identified with the bioinformatic tool PROSPER.

Contributor Information

M. Pineda, Email: Miguel.pineda@glasgow.ac.uk.

P. Bonay, Email: pbonay@cbm.csic.es.

References

- 1. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marin‐Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet 2010; 375:1388–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anez N. Studies on Trypanosoma rangeli Tejera, 1920. VII – its effect on the survival of infected triatomine bugs. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1984; 79:249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anez N, Nieves E, Cazorla D. Studies on Trypanosoma rangeli Tejera, 1920. IX. Course of infection in different stages of Rhodnius prolixus . Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1987; 82:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vasta GR. Galectins as pattern recognition receptors: structure, function, and evolution. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 946:21–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leffler H, Carlsson S, Hedlund M, Qian Y, Poirier F. Introduction to galectins. Glycoconj J 2004; 19:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamhawi S, Ramalho‐Ortigao M, Pham VM et al A role for insect galectins in parasite survival. Cell 2004; 119:329–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hernandez JD, Baum LG. Ah, sweet mystery of death! Galectins and control of cell fate. Glycobiology 2002; 12:127R–R136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newlaczyl AU, Yu LG. Galectin‐3 ‐ A jack‐of‐all‐trades in cancer. Cancer Lett 2011; 313:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Califice S, Castronovo V, Van Den Brule F. Galectin‐3 and cancer (Review). Int J Oncol 2004; 25:983–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krzeslak A, Lipinska A. Galectin‐3 as a multifunctional protein. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2004; 9:305–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meijers WC, Lopez‐Andres N, de Boer RA. Galectin‐3, Cardiac Function, and Fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2016; 186:2232–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmad N, Gabius HJ, Andre S et al Galectin‐3 precipitates as a pentamer with synthetic multivalent carbohydrates and forms heterogeneous cross‐linked complexes. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:10841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nieminen J, Kuno A, Hirabayashi J, Sato S. Visualization of galectin‐3 oligomerization on the surface of neutrophils and endothelial cells using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:1374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pineda MA, Corvo L, Soto M, Fresno M, Bonay P. Interactions of human galectins with Trypanosoma cruzi: binding profile correlate with genetic clustering of lineages. Glycobiology 2015; 25:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sa AR, Dias GB, Kimoto KY et al Genotyping of Trypanosoma cruzi DTUs and Trypanosoma rangeli genetic groups in experimentally infected Rhodnius prolixus by PCR‐RFLP. Acta Trop 2016; 156:115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sales‐Campos H, Kappel HB, Andrade CP et al A DTU‐dependent blood parasitism and a DTU‐independent tissue parasitism during mixed infection of Trypanosoma cruzi in immunosuppressed mice. Parasitol Res 2014; 113:375–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tomasini N, Diosque P. Evolution of Trypanosoma cruzi: clarifying hybridisations, mitochondrial introgressions and phylogenetic relationships between major lineages. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015; 110:403–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mejia‐Jaramillo AM, Pena VH, Triana‐Chavez O. Trypanosoma cruzi: biological characterization of lineages I and II supports the predominance of lineage I in Colombia. Exp Parasitol 2009; 121:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pineda MA, Cuervo H, Fresno M, Soto M, Bonay P. Lack of Galectin‐3 prevents cardiac fibrosis and effective immune responses in a murine model of Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1160–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pelletier I, Sato S. Specific recognition and cleavage of galectin‐3 by Leishmania major through species‐specific polygalactose epitope. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:17663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pelletier I, Hashidate T, Urashima T et al Specific recognition of Leishmania major poly‐beta‐galactosyl epitopes by galectin‐ 9: possible implication of galectin‐9 in interaction between L. major and host cells. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:22223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodriguez P, Montilla M, Nicholls S, Zarante I, Puerta C. Isoenzymatic characterization of Colombian strains of Trypanosoma cruzi . Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1998; 93:739–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uruena C, Santander P, Diez H et al Chromosomal localization of the KMP‐11 genes in the KP1(+) and KP1(–) strains of Trypanosoma rangeli . Biomedica 2004; 24:200–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koerich LB, Emmanuelle‐Machado P, Santos K, Grisard EC, Steindel M. Differentiation of Trypanosoma rangeli: high production of infective trypomastigote forms in vitro . Parasitol Res 2002; 88:21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wagner G, Eiko Yamanaka L, Moura H et al The Trypanosoma rangeli trypomastigote surfaceome reveals novel proteins and targets for specific diagnosis. J Proteomics 2013; 82:52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. John CM, Jarvis GA, Swanson KV et al Galectin‐3 binds lactosaminylated lipooligosaccharides from Neisseria gonorrhoeae and is selectively expressed by mucosal epithelial cells that are infected. Cell Microbiol 2002; 4:649–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Massa St, Cooper DNW, Leffelr H, Barondes SH. L‐29, an endogenous lectin, binds to glycoconjugate ligands with positive cooperativity. Biochemistry 1993; 32:260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersen H, Jensen ON, Moiseeva EP, Eriksen EF. A proteome study of secreted prostatic factors affecting osteoblastic activity: galectin‐1 is involved in differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res 2003; 18:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lei Z, Anand A, Mysore KS, Sumner LW. Electroelution of intact proteins from SDS‐PAGE gels and their subsequent MALDI‐TOF MS analysis. Methods Mol Biol 2007; 355:353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakayasu ES, Yashunsky DV, Nohara LL, Torrecilhas AC, Nikolaev AV, Almeida IC. GPIomics: global analysis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol‐anchored molecules of Trypanosoma cruzi . Mol Syst Biol 2009;5:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Santana JM, Grellier P, Schrevel J, Teixeira AR. A Trypanosoma cruzi‐secreted 80 kDa proteinase with specificity for human collagen types I and IV. Biochem J 1997; 325(Pt 1):129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kohatsu L, Hsu DK, Jegalian AG, Liu FT, Baum LG. Galectin‐3 induces death of candida species expressing specific beta‐1,2‐linked mannans. J Immunol 2006; 177:4718–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song J, Tan H, Perry AJ et al PROSPER: an integrated feature‐based tool for predicting protease substrate cleavage sites. PLOS ONE 2012; 7:e50300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Callejas‐Hernández F, Rastrojo A, Poveda C, Gironès N, Fresno M. Genomic assemblies of newly sequenced Trypanosoma cruzi strains reveal new genomic expansion and greater complexity. Sci Rep 2018; 8:14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD‐HIT: accelerated for clustering the next‐generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2012; 28:3150–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Duschak VG, Couto AS. Cruzipain, the major cysteine protease of Trypanosoma cruzi: a sulfated glycoprotein antigen as relevant candidate for vaccine development and drug target. A review. Curr Med Chem 2009; 16:3174–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen HY, Fermin A, Vardhana S et al Galectin‐3 negatively regulates TCR‐mediated CD4+ T‐cell activation at the immunological synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:14496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fermino ML, Dylon LS, Cecilio NT et al Lack of galectin‐3 increases Jagged1/Notch activation in bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells and promotes dysregulation of T helper cell polarization. Mol Immunol 2016; 76:22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nangia‐Makker P, Raz T, Tait L, Hogan V, Fridman R, Raz A. Galectin‐3 cleavage: a novel surrogate marker for matrix metalloproteinase activity in growing breast cancers. Cancer Res 2007; 67:11760–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ochieng J, Fridman R, Nangia‐Makker P et al Galectin‐3 is a novel substrate for human matrix metalloproteinases‐2 and ‐9. Biochemistry 1994; 33:14109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ochieng J, Leite‐Browning ML, Warfield P. Regulation of cellular adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins by galectin‐3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998; 246:788–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elmwall J, Kwiecinski J, Na M et al Galectin‐3 is a target for proteases involved in the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus . Infect Immun 2017; 85:e00177–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van de Wetering JK, van Golde LM, Batenburg JJ. Collectins: players of the innate immune system. Eur J Biochem 2004; 271:1229–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gazzinelli RT. Natural anti‐Gal antibodies prevent, rather than cause, autoimmunity in human Chagas’ disease. Res Immunol 1991; 142:164–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Milani SR, Travassos LR. Anti‐alpha‐galactosyl antibodies in chagasic patients. Possible biological significance. Braz J Med Biol Res 1988; 21:1275–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Almeida IC, Ferguson MA, Schenkman S, Travassos LR. GPI‐anchored glycoconjugates from Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes are recognized by lytic anti‐alpha‐galactosyl antibodies isolated from patients with chronic Chagas’ disease. Braz J Med Biol Res 1994; 27:443–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Almeida IC, Ferguson MA, Schenkman S, Travassos LR. Lytic anti‐alpha‐galactosyl antibodies from patients with chronic Chagas’ disease recognize novel O‐linked oligosaccharides on mucin‐like glycosyl‐phosphatidylinositol‐anchored glycoproteins of Trypanosoma cruzi . Biochem J 1994; 304:793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vray B, Camby I, Vercruysse V et al Up‐regulation of galectin‐3 and its ligands by Trypanosoma cruzi infection with modulation of adhesion and migration of murine dendritic cells. Glycobiology 2004; 14:647–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ferrer MF, Pascuale CA, Gomez RM, Leguizamon MS. DTU I isolates of Trypanosoma cruzi induce upregulation of Galectin‐3 in murine myocarditis and fibrosis. Parasitology 2014; 141:849–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reignault LC, Barrias ES, Soares Medeiros LC, de Souza W, de Carvalho TM. Structures containing galectin‐3 are recruited to the parasitophorous vacuole containing Trypanosoma cruzi in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Parasitol Res 2014; 113:2323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Almeida IC, Krautz GM, Krettli AU, Travassos LR. Glycoconjugates of Trypanosoma cruzi: a 74 kD antigen of trypomastigotes specifically reacts with lytic anti‐alpha‐galactosyl antibodies from patients with chronic Chagas’ disease. J Clin Lab Anal 1993; 7:307–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lindstedt R, Apodaca G, Barondes SH, Mostov KE, Leffler H. Apical secretion of a cytosolic protein by Madin–Darby canine kidney cells. Evidence for polarized release of an endogenous lectin by a nonclassical secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 1993; 268:11750–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guhl F, Vallejo GA. Trypanosoma (Herpetosoma) rangeli Tejera, 1920: an updated review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003; 98:435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grisard EC, Steindel M, Guarneri AA, Eger‐Mangrich I, Campbell DA, Romanha AJ. Characterization of Trypanosoma rangeli strains isolated in Central and South America: an overview. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1999; 94:203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stoco PH, Wagner G, Talavera‐Lopez C et al Genome of the avirulent human‐infective trypanosome – Trypanosoma rangeli . PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Buscaglia CA, Campo VA, Frasch AC, Di Noia JM. Trypanosoma cruzi surface mucins: host‐dependent coat diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006; 4:229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Grisard EC, Stoco PH, Wagner G et al Transcriptomic analyses of the avirulent protozoan parasite Trypanosoma rangeli . Mol Biochem Parasitol 2010; 174:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Belew AT, Junqueira C, Rodrigues‐Luiz GF et al Comparative transcriptome profiling of virulent and non‐virulent Trypanosoma cruzi underlines the role of surface proteins during infection. PLOS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moody TN, Ochieng J, Villalta F. Novel mechanism that Trypanosoma cruzi uses to adhere to the extracellular matrix mediated by human galectin‐3. FEBS Lett 2000; 470:305–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kleshchenko YY, Moody TN, Furtak VA, Ochieng J, Lima MF, Villalta F. Human galectin‐3 promotes Trypanosoma cruzi adhesion to human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Infect Immun 2004; 72:6717–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. MALDI‐TOF data of selected bands subjected to triptic digestion. Bands 1, 2 and 3 as indicated in figure 1B were isolated from SDS‐PAGE gels after Coomasie Blue Staining and proteins were destained and electroeluted using Proteo‐PLUS system, dialyzed overnight and subjected to trypsin digestion. Resulting peptides were analysed by MALDI‐TOF using a Bruker‐Daltonics Autoflex III. Predicted sequences based on the N‐terminal sequencing data, and predicted and observed molecular weight of triptic peptides are shown for each protein, bands 1, 2 and 3.

Fig. S2. Protein sequences of T. cruzi proteases identified with the bioinformatic tool PROSPER.