Abstract

The innate immune system is the first line of defense against invading pathogens. The retinoic acid‐inducible gene I (RIG‐I) like receptors (RLRs), RIG‐I and melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5), are critical for host recognition of viral RNAs. These receptors contain a pair of N‐terminal tandem caspase activation and recruitment domains (2CARD), an SF2 helicase core domain, and a C‐terminal regulatory domain. Upon RLR activation, 2CARD associates with the CARD domain of MAVS, leading to the oligomerization of MAVS, downstream signaling and interferon induction. Unanchored K63‐linked polyubiquitin chains (polyUb) interacts with the 2CARD domain, and in the case of RIG‐I, induce tetramer formation. However, the nature of the MDA5 2CARD signaling complex is not known. We have used sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation to compare MDA5 2CARD and RIG‐I 2CARD binding to polyUb and to characterize the assembly of MDA5 2CARD oligomers in the absence of polyUb. Multi‐signal sedimentation velocity analysis indicates that Ub4 binds to RIG‐I 2CARD with a 3:4 stoichiometry and cooperatively induces formation of an RIG‐I 2CARD tetramer. In contrast, Ub4 and Ub7 interact with MDA5 2CARD weakly and form complexes with 1:1 and 2:1 stoichiometries but do not induce 2CARD oligomerization. In the absence of polyUb, MDA5 2CARD self‐associates to forms large oligomers in a concentration‐dependent manner. Thus, RIG‐I and MDA5 2CARD assembly processes are distinct. MDA5 2CARD concentration‐dependent self‐association, rather than polyUb binding, drives oligomerization and MDA5 2CARD forms oligomers larger than tetramer. We propose a mechanism where MDA5 2CARD oligomers, rather than a stable tetramer, function to nucleate MAVS polymerization.

Keywords: analytical ultracentrifugation, innate immunity, K63‐linked polyubiquitin, multi‐signal sedimentation velocity, RIG‐I‐like receptors

1. INTRODUCTION

Retinoic acid‐inducible gene I (RIG‐I) and melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5) are cytoplasmic innate immune receptors that sense dsRNA produced by viruses to activate signaling pathways culminating in induction of type 1 interferon.1 These receptors share structural and functional homology. Both contain a tandem caspase activation and recruitment (CARD) signaling domain, referred to as 2CARD, at the N‐terminus and an SF2 helicase domain and a C‐terminal domain that are important for dsRNA recognition (Figure 1).2 The two receptors recognize particular dsRNA ligands and form distinct active signaling assemblies. RIG‐I is most potently activated by short (<0.5 kbp), 5′‐triphosphorylated, double‐stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) whereas MDA5 is most strongly stimulated by long (>0.1 kbp) dsRNAs, independent of the nature of the 5′‐ends.3, 4 MDA5 binds dsRNA via its helicase and CTD domains to form an extended filament.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 RIG‐I forms shorter polymeric complexes on dsRNA to promote signaling.10, 11 The downstream signaling adapter for both proteins is mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS). The CARD domain of MAVS interacts with the 2CARD domain of the RIG‐I like receptors (RLRs),12, 13, 14, 15 resulting in MAVS polymerization,16, 17 which activates downstream signaling pathways to induce types I and III interferons and other antiviral cytokines.

Figure 1.

Domain structures of retinoic acid‐inducible gene I (RIG‐I) and melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5). (a) The 2CARD domain is shown in red (CARD 1) and blue (CARD 2) and the helicase and C‐terminal domains are shown in gray. (b) Sequence alignment of RIG‐I and MDA5 2CARD showing polyUb binding sites. Residues in green on RIG‐I 2CARD interact with polyUb in the RIG‐I 2CARD crystal structure.20 For MDA5, residues aligned to polyUb‐binding residues of RIG‐I are shown in green and conserved amino acids are indicated by asterisks

Much of what is known regarding the role of 2CARD in signaling is based on structural and biochemical characterization of RIG‐I. In the absence of dsRNA, RIG‐I 2CARD is maintained in an autoinhibited state via intramolecular interaction with the helicase domain.18, 19 dsRNA binding relieves RIG‐I autoinhibition, resulting in the assembly of a 2CARD tetramer which induces MAVS polymerization.17, 20 RIG‐I signaling is modulated by binding of polymers of ubiquitin linked via K63 (unanchored polyUb) as well as covalent ubiquitination. Although the RIG‐I 2CARD domain is ubiquitinated at nine sites, Lys 172 and 164 are the most important for signaling.21 Binding of unanchored, polyUb or K63‐linked polyubiquitination at Lys172 stabilizes the RIG‐I 2CARD tetramer.20 Only one lysine of RIG‐I 2CARD, Lys164, is conserved in MDA5 2CARD (Lys 174), but no covalent K63 ubiquitination sites on the CARD domains of MDA5 have been identified.

Like RIG‐I, the 2CARD domain of MDA5 binds unanchored polyUb21 and mutation of Lys 174 prevents binding. However, in vitro polymerization of MAVS CARD is not induced by a mixture of polyUb and MDA5 2CARD, whereas a mixture of polyUb and RIG‐I's 2CARD does polymerize MAVS CARD.6 In the absence of polyUb, MDA5 2CARD can self‐associate and induce MAVS CARD oligomerization in vitro.6 MDA5 forms filaments on dsRNA in which the helicase domain wraps around the dsRNA6 and the 2CARD domain is tethered to the periphery of the filament via a ~100 amino acid linker. This increases the local concentration of MDA5 2CARD which may promote 2CARD oligomerization. This may provide insight as to why filament formation on dsRNA is crucial for signaling by MDA5, but not RIG‐I. However, it is not known whether polyUb binding to MDA5 2CARD controls self‐association or how this domain associates. Here, we have employed sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation to compare the interaction of polyUb with MDA5 2CARD and RIG‐I 2CARD and to characterize the assembly reactions of MDA5 2CARD.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Multisignal sedimentation velocity is a powerful method to assign the stoichiometries of multiprotein complexes that exploits spectral differences between interacting components.22 We have applied this approach to determine the size and stoichiometry of RIG‐I 2CARD and MDA5 2CARD complexes with polyUb chains. Preparations of RIG‐I and MDA5 2CARD and Ub4 were analyzed to assess their homogeneity and hydrodynamic parameters. The reagents are homogeneous (Figure 2a, d) and the molar masses deduced from the sedimentation velocity data agree with predicted values for the monomers (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Multi‐signal sedimentation velocity analysis of retinoic acid‐inducible gene I (RIG‐I) like receptor (RLR) 2CARD binding to K63‐linked Ub4. c(s) Distributions of: (a) 5 μM retinoic acid‐inducible gene I (RIG)‐I 2CARD and 5 μM Ub4 alone, (b) mixture of 5 μM RIG‐I 2CARD and 5 μM Ub4, (c) mixture of 5 μM RIG‐I and 20 μM Ub4, (d–f) same as a‐c, but samples contain melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5) 2CARD and Ub4. Peaks are labeled with the experimental molecular weights and the 2CARD: Ub4 stoichiometries. Data were collected at 20°C and 45,000 RPM using absorbance at 280 nm and Rayleigh interferometry. Note that the peak for free MDA5 2CARD shifts towards the Ub4 peak in panels (e) and (f). This likely represents an artifact arising from the c(s) deconvolution

Multisignal sedimentation velocity data collected from mixtures of 2CARD domains and polyUb were deconvoluted to produce c(s) distributions of the pure components. For RIG‐I, the distributions from an equimolar mixture of 2CARD domain and Ub4 have a peak associated with free Ub4 and an additional species at 7.9 S that contains both RIG‐I 2CARD and Ub4 (Figure 2b,c). No intermediate species are detected, suggesting that the assembly of this complex is highly cooperative. However, at slightly higher concentrations of NaCl (50 mM), intermediate complexes containing both RIG‐I and Ub4 are present at ~4, ~5 and ~6 S (Figure S2). The sedimentation coefficients and relative peak areas for the complex are essentially unchanged in the 4:1 mixture, indicating that formation of the 7.9 S species is saturated. The molar mass of this complex (Table S1) and the Ub4: RIG‐I stoichiometry indicate that it corresponds to a 3 Ub4: 4 RIG‐I complex. This stoichiometry agrees with the crystal structure of the tetrameric complex,20 but differs from previous biophysical analyses which reported a 4:4 complex.21

Under the same conditions, MDA5 2CARD interacts very differently with polyUb than RIG‐I (Figure 2). In a 1:1 mixture of Ub4 and MDA5 2CARD the 7.9 S complex is not formed but a peak at 4.1 S is detected and assigned to a 1:1 Ub4: 2CARD complex based on the composition and molecular mass. This feature does not shift upon addition of a four‐fold molar excess of Ub4, indicating that it corresponds to a distinct species. Addition of four equivalents of Ub4 induces formation of a 5.2 S feature assigned as either a species or a reaction boundary associated with the 2:1 species. In both the 1:1 and 4:1 mixtures, there is significant amounts of free MDA5 remaining, whereas free RIG‐I 2CARD domain is depleted under comparable conditions. Thus, Ub4 binds to MDA5 2CARD with lower affinity than to RIG‐I.

Because the minimum length for polyUb binding to MDA5 is reported to be longer (Ub4) than for RIG‐I (Ub2),21 we analyzed MDA5 2CARD mixtures containing longer chains to assess whether they may be capable of inducing MDA5 2CARD oligomerization (Figure 3). Peaks are present in the distribution at 4.7 and 6.4 S that correspond to Ub7:2CARD complexes with relative stoichiometries of 1.10 and 1.86, respectively. These stoichiometries agree with those found for the two peaks formed with Ub4 and MDA5 2CARD (Figure 2e,f). By analogy, they are assigned as the 1:1 complex and either a species or a reaction boundary associated with the 2:1 species. These analyses demonstrate that under the conditions where polyUb binding induces cooperative assembly of a RIG‐I 2CARD tetramer, MDA5 2CARD can bind at least two Ub4 or Ub7 molecules but they do not induce oligomerization. RIG‐I 2CARD contains two binding sites for polyUb.20 We predict that the polyUb binding sites of MDA5 2CARD are similar to those of RIG‐I as ~40% of the residues of RIG‐I that interact with ubiquitin in the RIG‐I 2CARD crystal structure20 are identical or similar (E/D) to the aligned residues of MDA5 (Figure 1b).

Figure 3.

Multi‐signal sedimentation velocity analysis of melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5) 2CARD binding to K63‐linked Ub7. C(s) distributions of (a) of 5 μM MDA5 2CARD and Ub7 alone. (b) Mixture of 5 μM MDA5 2CARD and 10 μM Ub7. Peaks are labeled with the experimental molecular weights and the 2CARD: Ub7 stoichiometries. Data were collected at 20°C and 45,000 RPM using absorbance at 280 nm and Rayleigh interferometry. Note that the peak for free MDA5 2CARD shifts towards the Ub7 peak in panels E and F. This likely represents an artifact arising from the c(s) deconvolution

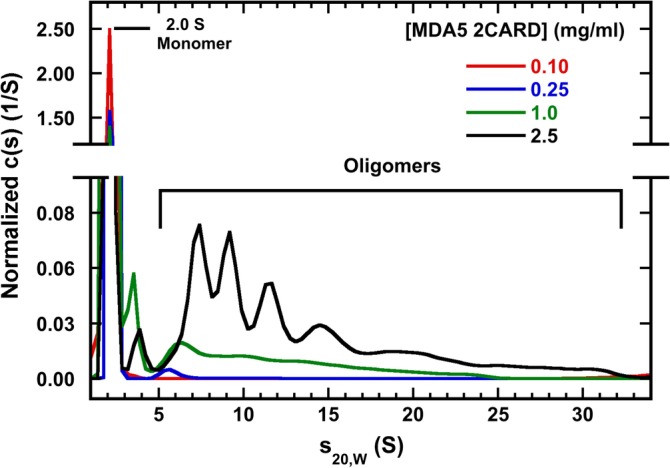

We analyzed the concentration‐dependent assembly of MDA5 2CARD in the absence of polyUb by sedimentation velocity to quantitatively assess self‐association. At the lowest protein concentrations, MDA5 2CARD sediments as a monomer at 2.0 S (Figure 4). As the concentration is increased, additional oligomers extending to ~25 S are formed comprising 25% of the material at 1 mg/ml. At the highest attainable concentration of 2.5 mg/ml, the content of oligomeric forms increases to 64% and the size range increases to beyond 30S. A tetramer of MDA5 2CARD is expected to sediment at about 4 S and it is interesting that the 2CARD oligomers are mostly larger than tetramer. Assuming a frictional ratio (f/f0) of 2.0–2.5, the largest oligomers are 2.5–3.5 MDa containing 100–150 2CARD monomers. The higher oligomers partially dissociate upon dilution. This broad distribution suggests an unlimited association model, as expected for assembly of MDA5 2CARD filaments. It was not possible to prepare sample at higher concentrations to probe whether the discrete peaks observed in the sample at 2.5 mg/ml correspond to intermediate assembly states or to hydrodynamic reaction boundaries.

Figure 4.

Concentration‐dependent self‐association of melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5) 2CARD. C(s) distributions of samples are presented for samples at loading concentrations of 0.1, 0.25, 1.0 and 2.5 mg/ml MDA5 2CARD. Data are normalized by area. Monomeric MDA5 2CARD was concentrated to the indicated concentration in AU20 buffer. Data were collected at 20°C and 50,000 RPM using Rayleigh interferometry. The aggregate populations are: 3.5, 17, 25 and 64% for the 0.1, 0.25, 1, and 2.5 mg/ml samples, respectively

Negative stain electron micrographs of MDA5 2CARD preparations reveal concentration‐dependent formation of filaments of ~15 nm in width with length up to ~100 nm (Figure S3). These dimensions are consistent with previous reports of filaments formed by MDA5 2CARD,6 suggesting that the broad size distribution we observe in the analytical ultracentrifuge corresponds to a mixture of filament assembly intermediates. Together, these data demonstrate that MDA5 2CARD self‐associates to form filamentous oligomers via an indefinite assembly model in a concentration‐dependent but polyUb‐independent manner.

In contrast to MDA5 2CARD, the RIG‐I construct remains predominantly monomeric at higher concentrations and does not assemble to large oligomers (Figure S4). At the highest attainable concentration (1 mg/mL), RIG‐I 2CARD forms some aggregates but the population is low (6%) and no material larger than 6S is detected.

Given that RIG‐I and MDA5 share a common adapter protein and likely utilize the same interface on the second CARD domain to activate MAVS,17 it is expected that they form analogous signaling platforms. The crystal structure of the Ub2: RIG‐I 2CARD tetrameric complex reveals a “lock washer” structure20 that is believed to nucleate the helical polymerization of MAVS CARD.17 Larger oligomers of MDA5 2CARD may play a similar role. In principle, the tandem CARD domains of MDA5 can assemble to form a two‐start, left‐handed helical filament that resembles the one‐start filament observed for MAVS itself,16, 17 and for the CARD domains of ASC and NLRC4,23 Caspase‐1,24 BCL10,25 and RIP2.26 CARD domains associate via three types of asymmetric interactions.27 Residues lying at the type IIa interface on the first CARD domain of MDA5, which would be involved this type of filament formation, are important for MDA5 signaling but not for RIG‐I.20, 28 Thus, MDA5 2CARD may signal to MAVS via one end of a filament using the type IIb interface of the second CARD. Formation of extended helical structure in MDA5 may be required for stability of the signaling platform and perhaps serves to selectively activate MDA5 upon interaction with longer dsRNAs that sequester a large number of MDA5 2CARD domains.

Although polyUb does not induce MDA5 2CARD oligomerization, it likely plays other functional roles. Ubiquitination of RIG‐I 2CARD at K164 is required for signaling of MAVS in in vivo, and this is important for RIG‐I localization. Ubiquitinated RIG‐I interacts with the ubiquitin binding domain of the protein WHIP which bridges RIG‐I to MAVS.29 Notably, the only lysine residue conserved between RIG‐I and MDA5 2CARD domain is K164 of RIG‐I (K174 of MDA5). Although ubiquitination at this site has not been observed, polyUb binding to MDA5 2CARD may be sufficient to promote localization of this receptor to MAVS via a similar complex as RIG‐I. Alternatively, polyUb interactions may regulate yet uncharacterized intermolecular binding events important for MDA5 function and regulation.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

RIG‐I and MDA5 2CARD were expressed as SUMO‐tagged constructs in pET15b and purified as previously described,30 with the exceptions that the Ni‐NTA elution buffer contained 300 mM imidazole and gel filtration chromatography to remove the cleaved SUMO tag was performed in AU20 buffer consisting of 20 mM 4‐(2‐hydroxyethyl)‐1‐piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 0.1 mM tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Ubiquitin was expressed in (DE3) pLysS cells. Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X‐1000, pH 7.6 by sonication and the lysate was centrifuged at 30,000g for 20 min. Contaminating proteins were removed by precipitation on ice by slowly adding glacial acetic acid to the supernatant until the pH reached 4.5. The solution was then stirred on ice for 30 min. The supernatant was clarified at 30,000g for 20 min and loaded onto a SP Sepharose fast flow cation exchange column. Ubiquitin was eluted with a 100 ml linear gradient of 0–500 mM NaCl in 50 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5 and further purified on a Superdex 75 16/60 column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0. PolyUb chains were prepared as previously described.31 Verification of K63 Ub chain linkage was performed by immunoblot (Figure S1).

Samples for analytical ultracentrifugation were prepared in AU20 buffer and loaded into two channel aluminum‐epon double‐sector synthetic boundary cells for meniscus matching sealed with sapphire windows. Sedimentation velocity data were collected in a Beckman‐Coulter XL‐I analytical ultracentrifuge. Partial specific volumes and solvent densities and viscosities were determined using SEDNTERP.32 Rayleigh interferometry data were analyzed in SEDFIT using the c(s) method.33 Multi‐signal data were collected by interferometry and absorbance at 280 nm and were analyzed using SEDPHAT.22 The absorbance extinction coefficients were refined as previously described.34

Samples for electron microscopy were prepared in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM TCEP, incubated for 2 min on a plasma‐cleaned carbon coated copper grid, rinsed with 4 drops of 1% uranyl acetate, and blotted dry. Images were recorded with a FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTWIN Transmission Electron Microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR).

Supporting information

Figure S1 Verification of K63 ubiquitin linkage.

Figure S2. Multi‐signal sedimentation velocity analysis of RIG‐I 2CARD binding to Ub4 in 50 mM NaCl.

Figure S3: Negative stain electron microscopy of MDA5 2CARD.

Figure S4. Concentration‐dependent self‐association of RIG‐I 2CARD.

Table S1. Properties of the polyUb:2CARD species observed in multi‐signal sedimentation velocity experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant to J.L.C. from the University of Connecticut Research Foundation. We thank Jeffrey Lary and Dr. Christopher Mayo for valuable discussions and technical expertise. Expression constructs for Ube1, UbcH13, and Uev1a were provided by Genentech. The monoubiquitin expression construct was a gift from Joshua Wand, and MDA5 and RIG‐I constructs were provided by Anna Pyle.

Zerbe CM, Mouser DJ, Cole JL. Oligomerization of RIG‐I and MDA5 2CARD domains. Protein Science. 2020;29:521–526. 10.1002/pro.3776

Funding information Research Foundation; University of Connecticut

REFERENCES

- 1. Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, et al. The RNA helicase RIG‐I has an essential function in double‐stranded RNA‐induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu C, Xu H, Ranjith‐Kumar CT, et al. The structural basis of 5′ triphosphate double‐stranded RNA recognition by RIG‐I C‐terminal domain. Structure. 2010;18:1032–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baum A, Sachidanandam R, García‐Sastre A. Preference of RIG‐I for short viral RNA molecules in infected cells revealed by next‐generation sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16303–16308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S, et al. 5′‐triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG‐I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peisley A, Lin C, Wu B, et al. Cooperative assembly and dynamic disassembly of MDA5 filaments for viral dsRNA recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:21010–21015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu B, Peisley A, Richards C, et al. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition, filament formation, and antiviral signal activation by MDA5. Cell. 2013;152:276–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berke IC, Modis Y. MDA5 cooperatively forms dimers and ATP‐sensitive filaments upon binding double‐stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2012;31:1714–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berke IC, Yu X, Modis Y, Egelman EH. MDA5 assembles into a polar helical filament on dsRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18437–18441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu Q, Qu K, Modis Y. Cryo‐EM structures of MDA5‐dsRNA filaments at different stages of ATP hydrolysis. Mol Cell. 2018;72:999–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peisley A, Wu B, Yao H, Walz T, Hur S. RIG‐I forms signaling‐competent filaments in an ATP‐dependent, ubiquitin‐independent manner. Mol Cell. 2013;51:573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kohlway A, Luo D, Rawling DC, Ding SC, Pyle AM. Defining the functional determinants for RNA surveillance by RIG‐I. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:772–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, et al. IPS‐1, an adaptor triggering RIG‐I‐ and Mda5‐mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, et al. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG‐I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437:1167–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu L‐G, Wang Y‐Y, Han K‐J, Li L‐Y, Zhai Z, Shu H‐B. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus‐triggered IFN‐beta signaling. Mol Cell. 2005;19:727–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seth RB, Sun L, Ea C‐K, Chen ZJ. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF‐kappaB and IRF 3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang Q‐X, Chen ZJ. MAVS forms functional prion‐like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell. 2011;146:448–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu B, Peisley A, Tetrault D, et al. Molecular imprinting as a signal‐activation mechanism of the viral RNA sensor RIG‐I. Mol Cell. 2014;55:511–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kowalinski E, Lunardi T, McCarthy AA, et al. Structural basis for the activation of innate immune pattern‐recognition receptor RIG‐I by viral RNA. Cell. 2011;147:423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kolakofsky D, Kowalinski E, Cusack S. A structure‐based model of RIG‐I activation. RNA. 2012;18:2118–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peisley A, Wu B, Xu H, Chen ZJ, Hur S. Structural basis for ubiquitin‐mediated antiviral signal activation by RIG‐I. Nature. 2014;509:110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiang X, Kinch LN, Brautigam CA, et al. Ubiquitin‐induced oligomerization of the RNA sensors RIG‐I and MDA5 activates antiviral innate immune response. Immunity. 2012;36:959–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Balbo A, Minor KH, Velikovsky CA, Mariuzza RA, Peterson CB, Schuck P. Studying multiprotein complexes by multisignal sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:81–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Y, Fu T‐M, Lu A, et al. Cryo‐EM structures of ASC and NLRC4 CARD filaments reveal a unified mechanism of nucleation and activation of caspase‐1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:10845–10852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lu A, Li Y, Schmidt FI, et al. Molecular basis of caspase‐1 polymerization and its inhibition by a new capping mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:416–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. David L, Li Y, Ma J, Garner E, Zhang X, Wu H. Assembly mechanism of the CARMA1‐BCL10‐MALT1‐TRAF6 signalosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1499–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gong Q, Long Z, Zhong FL, et al. Structural basis of RIP2 activation and signaling. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ferrao R, Wu H. Helical assembly in the death domain (DD) superfamily. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu B, Hur S. How RIG‐I like receptors activate MAVS. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;12:91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tan P, He L, Cui J, et al. Assembly of the WHIP‐TRIM14‐PPP6C mitochondrial complex promotes RIG‐I‐mediated antiviral signaling. Mol Cell. 2017;68:293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vela A, Fedorova O, Ding SC, Pyle AM. The thermodynamic basis for viral RNA detection by the RIG‐I innate immune sensor. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42564–42573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dong KC, Helgason E, Yu C, et al. Preparation of distinct ubiquitin chain reagents of high purity and yield. Structure. 2011;19:1053–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Laue TM, Shah B, Ridgeway TM. Pelletier SL computer‐aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins In: Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Analytical ultracentrifugation in biochemistry and polymer science. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 1992; p. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schuck P. Size‐distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Padrick SB, Brautigam CA. Evaluating the stoichiometry of macromolecular complexes using multisignal sedimentation velocity. Methods. 2011;54:39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Verification of K63 ubiquitin linkage.

Figure S2. Multi‐signal sedimentation velocity analysis of RIG‐I 2CARD binding to Ub4 in 50 mM NaCl.

Figure S3: Negative stain electron microscopy of MDA5 2CARD.

Figure S4. Concentration‐dependent self‐association of RIG‐I 2CARD.

Table S1. Properties of the polyUb:2CARD species observed in multi‐signal sedimentation velocity experiments.