Description

We describe the case of a 75-year-old woman with permanent atrial fibrillation and advanced chronic kidney disease who was referred with worsening dyspnoea. She previously underwent surgical mitral and aortic mechanical valve replacements in 1989 for severe mitral and aortic stenoses secondary to rheumatic heart disease. She subsequently developed high-grade atrioventricular block requiring single-chamber (VVIR) pacemaker implantation in 2009. In 2015, she had severe paravalvular leak from valve dehiscence and required a redo-aortic valve replacement. At presentation, her symptoms were in keeping with congestive heart failure with a New York Heart Association score of 3. Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed a dilated left ventricle (left ventricular internal diameter in diastole of 57 mm) with severely impaired function but otherwise normal functioning prosthetic valves. It was noted that the left atrium was poorly visualised on the scan. The reasons for her symptoms were ascribed to a high percentage of right ventricular pacing. Therefore, she was offered an upgrade of her pacemaker to a biventricular device.

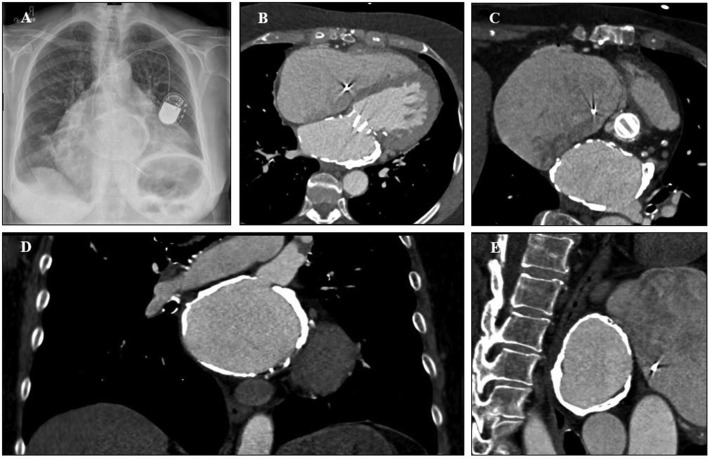

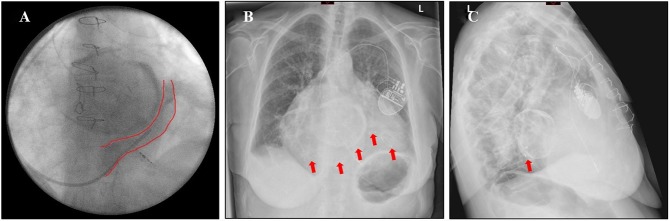

Pre-operative chest X-ray demonstrated a circular, radio-opaque lesion just within the cardiac silhouette (figure 1A). Cardiac CT with contrast revealed that this was due to severe left atrial (LA) calcification (figure 1B–E). During pacemaker implantation, cannulation of the coronary sinus (CS) was difficult due to a severely enlarged right atrium (RA) and abnormal angulation at the origin of the CS (figure 2A). Multiple specialised catheters were used before eventually achieving successful cannulation of the CS. Once within the CS, the left ventricular lead was advanced into a posterolateral position (figure 2B–C). The procedure was completed without any complications and she was discharged on the same day. During her follow-up visit at 4 months, she reported improvement in her overall symptoms.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray in posterior–anterior projection demonstrating a circular, radio-opaque lesion just within the cardiac silhouette (A); cardiac CT with contrast confirming severe LA calcification seen in the transverse (B); modified transverse (C); coronal (D) and sagittal (E) planes. LA, left atrial.

Figure 2.

Post-procedure fluoroscopy demonstrating the circular LA calcification and inferiorly displaced CS origin (A); and chest X-ray showing the left ventricular lead position in relation to the LA calcification in the anterior–posterior (B) and lateral (C) projections (red arrows display the position of the LV lead). CS, coronary sinus; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricle.

Left atrial calcification involving the appendage, free wall or mitral valve apparatus is not uncommon. However, severe LA calcification as encountered in our patient is very rare. It was first described by Oppenheimer in 1912,1 and is now referred to as ‘porcelain atrium’ or ‘coconut atrium’. It has been observed that the interatrial septum is usually spared in this condition. The most common cause appears to be due to rheumatic heart disease, although it has also been reported in end-stage renal failure with severe hyperparathyroidism2 and post-radiotherapy.3 Interestingly, in patients with rheumatic heart disease, the condition appears to develop a few decades after surgical valve intervention,4 as observed in our patient. It is often associated with atrial fibrillation, pulmonary congestion and arterial embolisation. Possible therapeutic options include surgical endoatriectomy. There are important surgical implications for patients needing redo-cardiac surgery due to issues with access. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of biventricular pacemaker implantation in a patient with porcelain left atrium, presenting with heart failure. It is impossible to determine from this single case whether severe LA calcification causes anatomical distortion of the CS origin, especially since our patient had a severely enlarged RA. Familiarity with radiological features of the condition will facilitate prompt recognition and prevent misdiagnosis.

Learning points.

Familiarity with radiological features of severe left atrial calcification will facilitate prompt recognition and prevent misdiagnosis.

It is important for physicians to be aware that a porcelain atrium has significant implications for future cardiac procedures.

Worsening heart failure may result from a high percentage of right ventricular only pacing and one possible treatment option is to insert an additional left ventricular lead, effectively providing cardiac resynchronisation therapy.

Footnotes

Contributors: WYD collected the data and drafted the manuscript. MM, AR and ZB critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Oppenheimer B. Calcification and osteogenic change of the left auricle in a case of auricular fibrillation. Proc NY Pathol Soc 1912;12:213–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Panayiotou A, Holloway B. Coconut atrium secondary to end-stage renal failure treated with long-term haemodialysis. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2433 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jenkins NP, Brooks NH, Greaves M. Coconut atrium following thoracic radiotherapy. Heart 2004;90 10.1136/hrt.2003.032698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee WJ, Son CW, Yoon JC, et al. . Massive left atrial calcification associated with mitral valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010;18:151–3. 10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]