SUMMARY

Penicillin allergies are not always lifelong. Approximately 50% are lost over five years

A reaction to penicillin during a childhood infection is unlikely to be a true allergy

Only 1–2% of patients with a confirmed penicillin allergy have an allergy to cephalosporins. In patients with a low risk of severe allergic reactions, cephalosporins are a relatively safe treatment option

Patients with a history of delayed non-severe reactions, such as mild childhood rashes that occurred over 10 years ago, may be suitable for an oral rechallenge with low-dose penicillin. This should be done in a supervised hospital environment

In many cases, with appropriate assessment and allergy testing, it may be possible to remove the penicillin allergy label

Keywords: beta-lactams, cephalosporins, hypersensitivity

Introduction

Most patients who say they have a penicillin allergy are not allergic to penicillins. While 10% of the population will report a penicillin allergy, less than 1% will be truly allergic.1,2 They have been erroneously labelled as penicillin-allergic.

In the USA, penicillin allergies are the most commonly documented drug allergy, with up to 20% of hospitalised patients having a recorded penicillin allergy.3,4 In Australian hospitals, national point prevalence data (2013–14) show that 8.9% of patients have a penicillin allergy label on their medical record.5 A high proportion of these labels are likely to be incorrect. The patient may have had a non-immune-mediated reaction such as nausea and vomiting, an exanthema (e.g. after taking amoxicillin during an Epstein-Barr virus infection) or an injection-site reaction.6,7

Impact of allergy labels

Patient-reported penicillin allergies alter antibiotic management and may result in the use of suboptimal or broader spectrum drugs such as fluoroquinolones, macrolides, glycopeptides and cephalosporins.6,8-11 Having a penicillin allergy label has been associated with an increased risk of Clostridium difficile, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci infections and colonisation.3 The increased use of broad-spectrum drugs in hospitalised patients with penicillin allergies also contributes to the growing global problem of antimicrobial resistance.6,9,12,13 Antibiotic allergy labels are correlated with increases in length of hospital stay,3 hospital readmission rates,10 surgical site infections,14 and admissions to intensive care units.15 Similarly in general practice, penicillin allergy labels are associated with an increased risk of death and MRSA infection or colonisation.16

Impermanent allergy

It has been demonstrated that more than 90% of patients labelled as having a penicillin allergy would be able to tolerate penicillins following appropriate assessment and allergy testing.17-19 Even penicillin allergies confirmed by skin tests can wane over time. Half the patients who have a positive skin test for penicillins will lose that reactivity after five years.13,20 There is therefore interest in penicillin allergy ‘de-labelling’. This is the removal of the allergy label following either allergy history reconciliation or testing (oral provocation or skin testing).

What is true penicillin allergy?

The classification of a patient-reported penicillin allergy label is the first important step in appropriate care (Table 1). Before prescribing, ask patients about their allergies, as not all allergies may have been documented in their medical records. Conversely, some reactions labelled as allergic may be other types of adverse events. Ask about the clinical features of suspected reactions.

Table 1. Antibiotic allergy classifications.

| Type | Mechanism | Clinical examples | Common antibiotic examples | Antibiotic recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A adverse drug reactions – non-immune-mediated | ||||

| Non-severe | Pharmacologically predictable reactions | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, pruritis (without rash), headache | Beta-lactams | Use all antibiotics |

| Severe | Encephalitis, renal impairment, tendinopathy | Cefepime, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones | Only avoid the implicated drug or dose | |

| Type B adverse drug reactions – immune-mediated | ||||

| 1 | IgE-mediated | Urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, anaphylaxis | Penicillins, cephalosporins | Avoid implicated drug. Caution with drugs in the same class and structurally related drugs |

| 2 | Antibody (usually IgG)-mediated cell destruction | Haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, vasculitis | Penicillins, cephalosporins | |

| 3 | IgG or IgM and complement | Fever, rash, arthralgia | Penicillin, amoxicillin, cefaclor | |

| 4 | T-cell mediated | Maculopapular exanthema, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis | Beta-lactams, glycopeptides, sulfonamides | Avoid implicated drug, drugs in the same class and structurally related drugs |

| Anaphylactoid reactions – non-immune-mediated | ||||

| Non-IgE-mediated | Direct mast-cell stimulation or basophil activation | Flushing, itching, urticaria, angioedema | Vancomycin, macrolides, fluoroquinolones | Manage the reaction, either by slowing the infusion or premedication (with antihistamines or corticosteroids) |

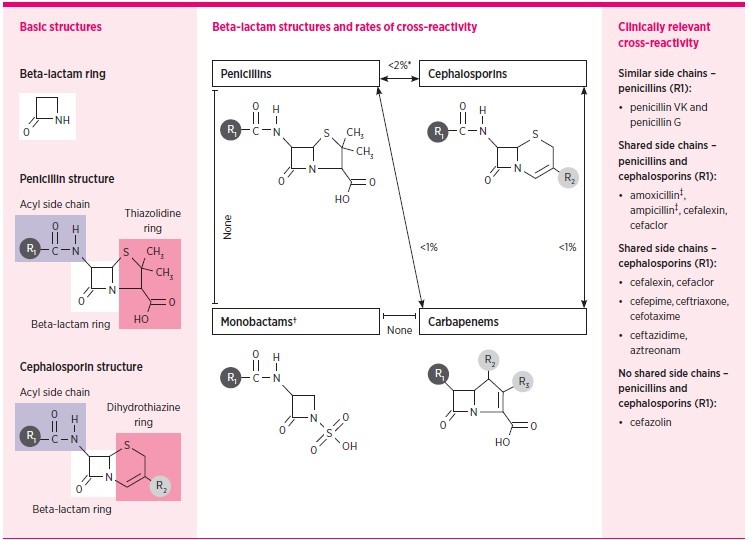

Allergic cross-reactivity

The beta-lactam antibiotics include penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and monobactams. Previously it was thought that patients with penicillin allergies had a 10% risk of cross-reactivity with cephalosporins and carbapenems.21 However, reviews have reported that the risk of cross-reactivity between cephalosporins, carbapenems and penicillins may be as low as 1%.21-24

The cross-reactivity between beta-lactam antibiotics may be due to the beta-lactam ring itself, an adjacent thiazolidine or dihydrothiazine ring, or from the side chains (R1 in penicillins or R1 and R2 in cephalosporins) – see Fig. 1. True cross-reactivity is largely due to the R1 side chains, with the highest risk being in beta-lactams with identical side chains.

Fig. 1.

Rates of cross-reactivity between beta-lactam antibiotics

| Beta-lactam antibiotics include penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and monobactams. |

| The left panel shows basic structures of beta-lactam antibiotics. Cross-reactivity is possible through the core beta-lactam ring, adjacent thiazolidine (penicillin) or dihydrothiazine (cephalosporin) ring, and also from a side chain (R1 or R2). Cephalosporins have both R1 and R2 side chains while penicillins only have R1. Despite varied mechanisms, true cross-reactivity is largely based on R1 side chains. Identical side chains in patients with IgE-mediated allergy pose the highest risk. However, cross-reactivity from side chains that are similar, but not identical, and from R2 side chain similarity, is possible and reported. |

| The centre panel demonstrates the structure and rates of cross-reactivity between penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and monobactams. |

| The right panel details the most clinically important cross-reactivity considerations. |

| *Except for shared group aminopenicillins and cephalosporins. |

| † Monobactams have no shared cross-reactivity with other beta-lactams, with the exception for aztreonam and ceftazidime, which share an identical R1. |

| ‡ Amoxicillin and ampicillin are structurally similar aminopenicillins and should be considered clinically cross-reactive with each other and the respective cephalosporins with shared R1 side chains listed in the figure. Similar considerations exist for the aminocephalosporins. |

| Source: Adapted from Blumenthal et al. (with permission)22 |

Cross-reactivity is particularly seen with aminopenicillins (amoxicillin, ampicillin) and aminocephalosporins (cefalexin, cefaclor, cefadroxil, ceprozil).24 The rate of cross-reactivity between aminopenicillins and aminocephalosporins has been reported to be as high as 30–40% in predominately European studies.23,25-27 At the antibiotic allergy testing centres of Austin Health and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, out of 15 patients reporting a severe-immediate cefalexin hypersensitivity, intradermal tests determined that six (40%) would not be able to tolerate ampicillin.5,28

While the data regarding cross-reactivity have primarily been about immediate hypersensitivities, similar patterns have been reported in non-severe delayed penicillin allergies.29,30 There are limited data regarding cross-reactivity in severe delayed reactions, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. For these severe delayed reactions, information regarding cross-reactivity is not a reliable guide for empirical prescribing.

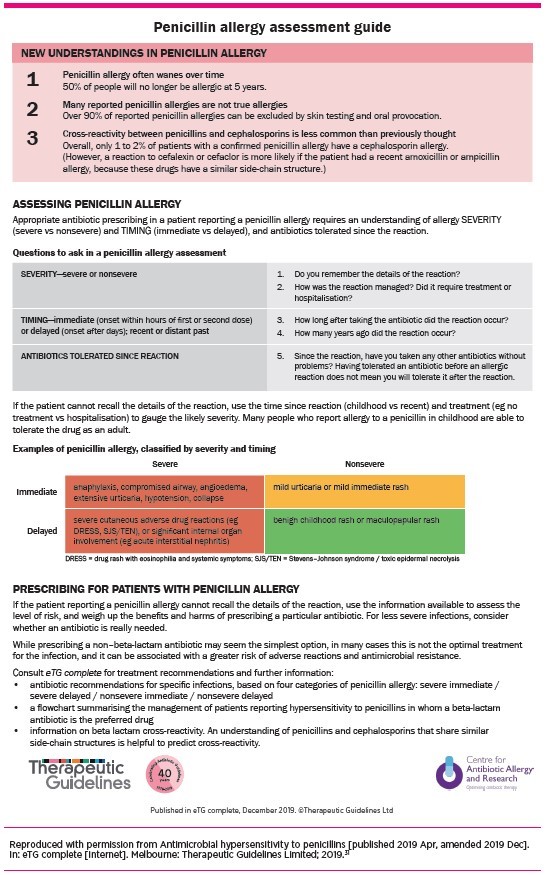

Assessing penicillin allergies

The key to both prescribing and de-labelling for patients with a history of penicillin allergy is an accurate assessment. This involves an understanding of the allergy particularly the severity, timing and tolerance. Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic contains a guide for this assessment (Fig. 2).31

Fig. 2.

Penicillin allergy assessment guide

Severity

An understanding of the severity of an allergy includes obtaining a description of its ‘type’. Information can be obtained by asking about how the reaction was managed, for example, was the patient hospitalised? What treatments were given for the reaction (e.g. adrenaline (epinephrine), antihistamine, systemic steroids or no therapy)? Simply asking the patient if the reaction was ‘severe’ is unlikely to gather accurate information.

Timing

The timing of the reaction is important to determine if it was delayed (e.g. T-cell mediated reaction) or immediate (e.g. IgE-mediated reaction). Immediate reactions typically occur within a ‘few hours’ of the first or second dose of the antibiotic. A delayed reaction usually occurs after ‘days’ of taking the antibiotic and the reaction can be accelerated if the antibiotic is given again.

Ask how many years ago the reaction occurred. This is important for assessing the likelihood that the penicillin allergy has persisted. In patients with true immediate penicillin allergies, the response wanes over time, with 80% of patients becoming tolerant to penicillins after 10 years.32

Tolerance

The patient should be questioned about antibiotics that they have tolerated since the reaction, particularly oral penicillins or cephalosporins. Antibiotics that have been tolerated following the reaction should be considered first. Being able to tolerate a specific antibiotic before the reaction does not predict tolerance following the reaction.

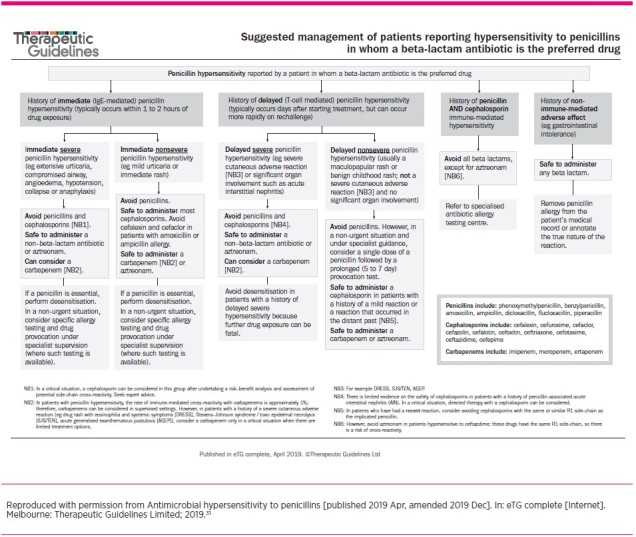

Risk assessment

The assessment of penicillin allergy enables classification of phenotypes as either severe versus non-severe and immediate versus delayed. This is helpful in stratifying the risk of using alternative beta-lactam antibiotics. Recommendations for prescribing based on the phenotypes appear in the Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic (Fig. 3).31

Fig. 3.

Suggested management of patients reporting hypersensitivity to penicillins in whom a beta-lactam antibiotic is the preferred drug

There are tools that can be used to aid in the assessment of penicillin allergies.32-34 An example is the Antibiotic Allergy Assessment Tool.34 This underwent multidisciplinary validation by nursing staff, pharmacists, junior and senior medical staff with no training in allergy. It has subsequently been used by hospital pharmacists and nurses to assess beta-lactam allergy labels.35 This tool classifies penicillin allergies into colour-coded risk groups and suggests an appropriate method for de-labelling:34,36

no risk – direct ‘de-label’

low risk – potential direct oral rechallenge

moderate risk – formal skin testing required before oral rechallenge

high risk – formal allergy assessment (may include skin testing).

Table 2 shows an extract of the Antibiotic Allergy Assessment Tool.

Table 2. Extract from the Antibiotic Allergy Assessment Tool.

| Clinical manifestation | Recommendation and resultant allergy type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatological | ||||

| Childhood exanthem (unspecified) Details of rash timing unknown and no severe features or hospitalisation Diffuse rash or localised rash with no other symptoms developing >24 hours after starting antibiotic, over 10 years ago |

Unlikely to be significant (non-severe) Unlikely to be significant (non-severe) Delayed hypersensitivity (non-severe, low-risk) |

|||

| Liver | ||||

| Hepatic enzyme derangement (does not meet criteria for liver failure or severe injury) | Unlikely to be immune-mediated (non-severe, low-risk) | |||

| Neurological or gastrointestinal | ||||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) Neurological or central nervous system manifestation (headache, optic neuritis, confusion, depression, mood disorder, low mood, psychosis) |

Unlikely to be immune-mediated (non-severe, low-risk) Unlikely to be immune-mediated (non-severe, low-risk) |

|||

| Renal | ||||

| Renal impairment (does not meet criteria for renal failure or severe injury) | Unlikely to be immune-mediated (non-severe, low-risk) | |||

| Unknown reaction | ||||

| Unknown reaction >10 years ago or family history of penicillin allergy only | Unlikely to be significant (non-severe, low-risk) | |||

| Appropriate for supervised direct oral rechallenge | Appropriate for direct de-labelling – removal of allergy label without testing (oral rechallenge if required) | |||

Note: This extract of the tool does not include clinical manifestations such as angioedema and haematological adverse reactions, which require further investigation.

Source: Reference 34

De-labelling

Non-immune-mediated adverse drug reactions (type A) are not true allergic reactions. Common examples are gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. If a patient has been labelled as penicillin-allergic because of a type A reaction, this should not stop the prescribing of beta-lactam antibiotics and patients do not need to undergo allergy testing. These labels should be directly removed from the patients’ medical records after a discussion about the nature of these reactions and the potential for treatment failure and adverse events if these antibiotics are avoided.

In severe type A reactions, the implicated drug should be avoided. However, it may be possible to use other drugs in the same class.

Sometimes allergies are reported reflecting the history of a family member rather than the patient. These spurious cases of allergy can usually be de-labelled.

Oral rechallenge

If there was a delayed, non-severe reaction (such as mild childhood rashes or a maculopapular rash that occurred over 10 years ago) an oral rechallenge with low-dose penicillin can be considered. Increasing evidence supports this in patients with a low risk of severe reactions, but the rechallenge should be in a supervised hospital environment.37,38 At present, there is limited evidence for trying an oral rechallenge in general practice.

Considering which penicillin to use in an oral rechallenge is important as patients can retain hypersensitivity to one penicillin (e.g. amoxicillin) while tolerating another (e.g. penicillin VK) due to variations in the antibiotic R1 side chains. Before the widespread use of amoxicillin, most ‘penicillin allergies’ would be secondary to penicillin VK or G. This should guide the drug to be used for the rechallenge if the ‘penicillin’ is unspecified. For example, if the patient’s allergy dated back to the 1960s, it would be appropriate to use penicillin VK in the rechallenge.

Prescribing for patients with penicillin allergies

Treatment options for patients with a penicillin allergy can be difficult. Prescribing should be guided by the information obtained from a thorough allergy assessment. Detailed advice regarding the use of cephalosporins and carbapenems is given in the Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic (Fig. 3).31

Conclusion

While penicillin allergies can be life-threatening, it is important to ensure that all patients with a recorded penicillin allergy label undergo a thorough antibiotic allergy assessment. These labels should be removed if the patient did not have a true immune-mediated reaction. An assessment of the severity, timing and tolerance of allergic reactions will lead to more ‘de-labelling’ and improved prescribing.

If there has been a presumed immune-mediated reaction, formal antibiotic allergy testing should be considered. While the management of patients with a penicillin allergy can be challenging, the cross-reactivity between penicillins and other beta-lactams is lower than initially reported. In patients with a low risk of severe allergic reactions, cephalosporins can be considered as an appropriate treatment option to penicillins.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Trubiano JA, Adkinson NF, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy is not necessarily forever. JAMA 2017;318:82-3. 10.1001/jama.2017.6510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet 2019;393:183-98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:790-6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trubiano JA, Thursky KA, Stewardson AJ, Urbancic K, Worth LJ, Jackson C, et al. Impact of an integrated antibiotic allergy testing program on antimicrobial stewardship: a multicenter evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:166-74. 10.1093/cid/cix244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trubiano JA, Chen C, Cheng AC, Grayson ML, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (NAPS) Antimicrobial allergy ‘labels’ drive inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing: lessons for stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:1715-22. 10.1093/jac/dkw008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sousa-Pinto B, Cardoso-Fernandes A, Araújo L, Fonseca JA, Freitas A, Delgado L. Clinical and economic burden of hospitalizations with registration of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:190-194.e2. 10.1016/j.anai.2017.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knezevic B, Sprigg D, Seet J, Trevenen M, Trubiano J, Smith W, et al. The revolving door: antibiotic allergy labelling in a tertiary care centre. Intern Med J 2016;46:1276-83. 10.1111/imj.13223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacco KA, Bates A, Brigham TJ, Imam JS, Burton MC. Clinical outcomes following inpatient penicillin allergy testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2017;72:1288-96. 10.1111/all.13168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigona NS, Steele JM, Miller CD. Impact of a pharmacist-driven beta-lactam allergy interview on inpatient antimicrobial therapy: A pilot project. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2016;56:665-9. 10.1016/j.japh.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacFadden DR, LaDelfa A, Leen J, Gold WL, Daneman N, Weber E, et al. Impact of reported beta-lactam allergy on inpatient outcomes: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:904-10. 10.1093/cid/ciw462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang KG, Cluzet V, Hamilton K, Fadugba O. The impact of reported beta-lactam allergy in hospitalized patients with hematologic malignancies requiring antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:27-33. 10.1093/cid/ciy037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Wolfson AR, Berkowitz DN, Carballo VA, Balekian DS, et al. Addressing inpatient beta-lactam allergies: a multihospital implementation. J All Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:616-25 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:686-93. 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:329-36. 10.1093/cid/cix794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy 2011;31:742-7. 10.1592/phco.31.8.742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West RM, Smith CJ, Pavitt SH, Butler CC, Howard P, Bates C, et al. ‘Warning: allergic to penicillin’: association between penicillin allergy status in 2.3 million NHS general practice electronic health records, antibiotic prescribing and health outcomes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019;74:2075-82. 10.1093/jac/dkz127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, Phillips E. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de-labeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:365-34.e1. 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macy E, Ngor EW. Safely diagnosing clinically significant penicillin allergy using only penicilloyl-poly-lysine, penicillin, and oral amoxicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013;1:258-63. 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen JR, Khan DA. Evaluation of penicillin allergy in the hospitalized patient: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2017;17:40. 10.1007/s11882-017-0706-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanca M, Torres MJ, García JJ, Romano A, Mayorga C, de Ramon E, et al. Natural evolution of skin test sensitivity in patients allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:918-24. 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70439-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campagna JD, Bond MC, Schabelman E, Hayes BD. The use of cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a literature review. J Emerg Med 2012;42:612-20. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet 2019;393:183-98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romano A, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Maggioletti M, Quaratino D, Gaeta F. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of cephalosporins in patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1662-72. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trubiano JA, Stone CA, Grayson ML, Urbancic K, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, et al. The 3 Cs of antibiotic allergy-classification, cross-reactivity, and collaboration. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:1532-42. 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips E, Knowles SR, Weber EA, Blackburn D. Cephalexin tolerated despite delayed aminopenicillin reactions. Allergy 2001;56:790. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.056008790.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romano A, Gaeta F, Arribas Poves MF, Valluzzi RL. Cross-Reactivity among Beta-Lactams. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2016;16:24. 10.1007/s11882-016-0594-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miranda A, Blanca M, Vega JM, Moreno F, Carmona MJ, García JJ, et al. Cross-reactivity between a penicillin and a cephalosporin with the same side chain. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;98:671-7. 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)70101-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trubiano JA, Tan N, Douglas A, Holmes NE, Chua K, Stevenson W, et al., editors. The impacts of an AMS-led antibiotic allergy testing program – a tertiary referral centre experience. ASID Annual Scientific Meeting 2019; 2019 May 16–18; Darwin, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Maggioletti M, Caruso C, Quaratino D. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of aztreonam and cephalosporins in subjects with a T cell-mediated hypersensitivity to penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;138:179-86. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Alonzi C, Maggioletti M, Zaffiro A, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity to carbapenems in patients with delayed hypersensitivity to penicillins. Allergy 2013;68:1618-21. 10.1111/all.12299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antimicrobial hypersensitivity [published 2019 Apr; amended 2019 Dec]. In: eTG complete [Internet]. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2019. www.tg.org.au

- 32.Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA 2019;321:188-99. 10.1001/jama.2018.19283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiriac AM, Banerji A, Gruchalla RS, Thong BY, Wickner P, Mertes PM, et al. Controversies in drug allergy: drug allergy pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:46-60.e4. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devchand M, Urbancic KF, Khumra S, Douglas AP, Smibert O, Cohen E, et al. Pathways to improved antibiotic allergy and antimicrobial stewardship practice: The validation of a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy assessment tool. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:1063-1065.e5. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.07.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devchand M, Kirkpatrick CM, Stevenson W, Garrett K, Perera D, Khumra S, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led penicillin allergy de-labelling ward round: a novel antimicrobial stewardship intervention. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019;74:1725-30. 10.1093/jac/dkz082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brockow K. Triage strategies for clarifying reported betalactam allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:1066-7. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trubiano JA, Smibert O, Douglas A, Devchand M, Lambros B, Holmes NE, et al. The safety and efficacy of an oral penicillin challenge program in cancer patients: a multicenter pilot study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy306. 10.1093/ofid/ofy306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2019;19:27. 10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FURTHER READING

- Yuson CL, Katelaris CH, Smith WB. ‘Cephalosporin allergy’ label is misleading. Aust Prescr 2018;41:37-41. 10.18773/austprescr.2018.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]