Abstract

Residues of the second extracellular loop are believed to be important for ligand recognition in adenosine receptors. Molecular modeling studies have suggested that one such residue, Gln167 of the human A3 receptor, is in proximity to the C2 moiety of some adenosine analogs when bound. Here this putative interaction was systematically explored using a neoceptor strategy, i.e., by site-directed mutagenesis and examination of the affinities of nucleosides modified to have complementary functionality. Gln167 was mutated to Ala, Glu, and Arg, while the 2-position of several adenosine analogs was substituted with amine or carboxylic acid groups. All compounds tested lost affinity to the mutant receptors in comparison to the wild type. However, comparing affinities among the mutant receptors, several compounds bearing charge at the 2-position demonstrated preferential affinity for the mutant receptor bearing a residue of complementary charge. 13, with a positively-charged C2 moiety, displayed an 8.5-fold increase in affinity at the Q167E mutant receptor versus the Q167R mutant receptor. Preferential affinity for specific mutant receptors was also observed for 8 and 12. The data suggests that a direct contact is made between the C2 substituent of some charged ligands and the mutant receptor bearing the opposite charge at position 167.

Keywords: G protein–coupled receptor, Purines, Neoceptor, Mutagenesis, Extracellular loop

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular adenosine receptors are classified into four distinct subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) and constitute an attractive target for drug design.[1-6] Agonists of the A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR), for instance, have been shown to be cardioprotective and cerebroprotective in several ischemic models.[5,6] Additionally, activation of the A3AR may also elicit an anti-cancer effect.[7] While these potential therapeutic applications warrant careful study of the receptor-ligand interactions of the A3AR, the incisiveness of such efforts has been confounded by the lack of a crystal structure of the receptor. In the family of Class I GPCRs to which adenosine receptors belong, only bovine rhodopsin has had its crystal structure solved at high resolution.[8] Consequently, defining the orthosteric binding site of the A3AR and other adenosine receptors has been achieved primarily through indirect means with the tools of computational modeling, synthetic chemistry, and classical pharmacology.

Previous studies of the A3AR in this lab and others have suggested that the binding site is defined primarily by transmembrane helical domains (TMs) 3, 5, 6, 7 and extracellular loop 2 (EL2).[9] Of these domains, the role of EL2 in ligand binding is the least well-characterized. However, it is believed that this domain of the A3AR and other GPCRs may play an important role in ligand recognition.[10-12] A recent model put forth by this laboratory posited a putative interaction between Gln167 of EL2 and the C2 substituent of N6-methyl substituted adenosine analogs.[13] Substitutions at the 2-positions of adenosine analogs have been shown to modulate affinity at the A3 subtype, with several 2-substituted compounds exhibiting enhanced affinity at the receptor when compared to their unsubstituted counterparts.[14] Thus, elucidating the amino acid residues that are involved in recognition of the 2-position could prove useful for future drug development efforts by achieving greater subtype selectivity.

One method of verifying putative interactions between a ligand moiety and a given GPCR is by taking advantage of the neoceptor approach.[15] This approach was developed for A2A and A3ARs as a method of engineering receptors by creating a mutant receptor (neoceptor) that is selectively activated by a novel synthetic ligand (neoligand) at concentrations that do not activate the native receptor.[15,16] Applied to exploring atomic interactions between ligand and receptor, a receptor residue and ligand moiety which are thought to be in close proximity can be modified in a complementary fashion so that the two groups exhibit a novel mode of interaction, e.g., exchanging a hydrogen bonding interaction for a salt bridge or reversal of hydrogen bonding pairs. The resulting impact on affinity can reveal details about the interaction between a ligand moiety and receptor residue of interest. If a stabilizing interaction exists between these two groups, an increase in affinity is expected at the mutant receptor relative to the wild type.

In order to probe the potential role of Gln167 in ligand recognition, we mutated this amino acid residue to alanine, arginine, and glutamic acid. According to rhodopsin-based homology modeling of the A3AR, the side chain of this residue in EL2 projects into the putative ligand binding site.[9] The importance of EL2 in small molecule ligand recognition was first noted for the ARs in a study of chimeric receptors.[17] Based on this model, a charged 2-position substituent of nucleoside ligands could, in theory, form a salt bridge with a residue bearing a side chain of the opposite charge. This was tested in the present study using known ligands that bore charged groups (e.g., −NH3+ or −COO−) at the 2-position, with some compounds exhibiting a charged group in proximity to the adenine ring while in others it was distal.

METHODS

Oligonucleotides used were synthesized by Bioserve Biotechnologies (Laurel, Maryland). 125I-AB-MECA (2000 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham Biosciences (Amersham, United Kingdom). Adenosine deaminase, CGS15943, compounds 12-14, and NECA were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri). Compounds 4-11 were synthesized as described.[13] All other compounds were obtained from standard commercial sources and were of analytical grade.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The protocols used were as described in the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, California). Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used for transfection of WT and mutant receptor cDNA to HEK-293 cells using manufacturer’s protocol.

Membrane Preparation

After 48 h of transfection, HEK-293 cells were harvested and homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in the 50 mM Tris•HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and stored at −80°C in aliquots. The protein concentration was determined by using the method of Bradford.[18]

Radioligand Binding Assay

The procedures of 125I-AB-MECA binding to WT and mutant human A3ARs were similar to those previously described.[9,12] Briefly, the membranes (20 μg of protein) were incubated with 0.8 nM 125I-AB-MECA in duplicate, with increasing concentrations of the competing compounds, in a final volume of 0.25 mL Tris•HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) at 25°C for 60 min. Binding reactions were terminated by filtration through Whatman GF/B glass-fiber filters under reduced pressure with an MT-24 cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, Maryland). Samples were counted using a Packard Cobra 5500 gamma counter (Packard Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

Binding parameters were estimated with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, California). IC50 values obtained from competition curves were converted to Ki values by using the Cheng-Prusoff equation.[19] Data were expressed as mean ± standard error.

RESULTS

Mutational Effects on Binding of Known Agonist and Antagonist

Competitive binding assays with 125I-AB-MECA were carried out at the WT and mutant A3ARs. Ki values for various known ligands (Figure 1) are shown in Table 1.

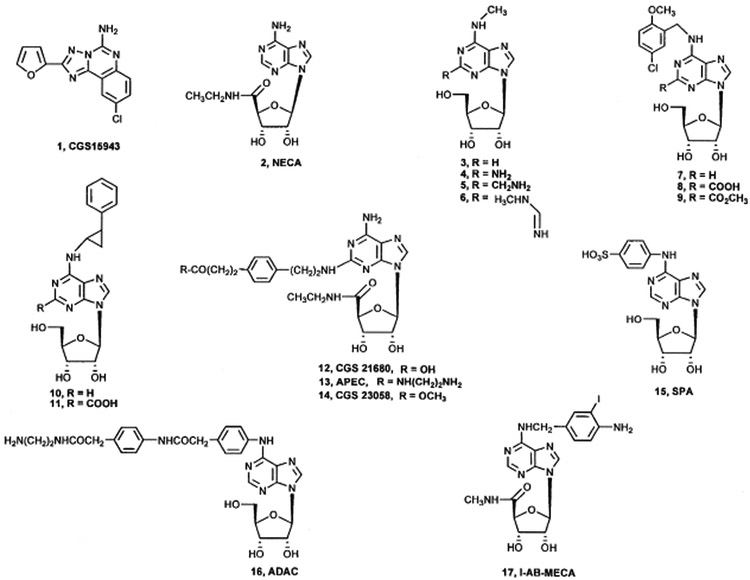

FIGURE 1.

Structures of compounds tested for affinity at hA3AR and Q167A/E/R mutant receptors. 17 was used as the radioligand in receptor binding experiments.

TABLE 1.

Binding Affinity of N6 and C2-Modified Adenosine Derivatives at Wild-type and Mutant Human A3ARs Expressed in HEK-293 Cells

| Compounda | N6 | C2 | Ki (nM)b hA3 AR WT |

Ki (nM)b Q167A |

Ki (nM)b Q167E |

Ki (nM)b Q167R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.2 ± 2.0 | 94.8 ± 20.4 | 71.8 ± 4.5 | 87.1 ± 26.3 | ||

| 2 | H | H | 46.2 ± 12.1 | 893 ± 155 | 918 ± 191 | 1230 ± 280 |

| 3 | CH3 | H | 8.2 ± 2.4 | 52.5 ± 14.4 | 81.5 ± 33.1 | 52.0 ± 15.3 |

| 4 | CH3 | NH2 | 57.1 ± 17.7 | 551 ± 136 | 406 ± 91 | 477 ± 129 |

| 5 | CH3 | CH2NH2 | 775 ± 230 | 7590 ± 1520 | 8030 ± 1790 | 7040 ± 1420 |

| 6 | CH3 | CH(=NH)-NHCH3 | 5500 ± 1700 | 16,200 ± 3900 | 10,800 ± 3400 | >10,000 |

| 7 | 5-Chloro-2-methoxy-benzyl | H | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 12.6 ± 3.3 | 26.3 ± 5.5 | 11.8 ± 1.3 |

| 8 | 5-Chloro-2-methoxy-benzyl | COOH | 274 ± 96 | 794 ± 161 | 1500 ± 340 | 397 ± 71 |

| 9 | 5-Chloro-2-methoxy-benzyl | CO2CH3 | 21.1 ± 8.0 | 65.8 ± 10.8 | 56.2 ± 8.2 | 81.8 ± 11.6 |

| 10 | trans-2-phenyl-1-cyclopropyl | H | 17.0 ± 9.3 | 36.6 ± 17.0 | 56.6 ± 22.3 | 37.8 ± 1.8 |

| 11 | trans-2-phenyl-1-cyclopropyl | COOH | 1260 ± 340 | 9350 ± 1270 | 5310 ± 1280 | >10,000 |

| 12 | H | NH(CH2)2φ(CH2)2-COOH* | 665 ± 152 | 8130 ± 3060 | 5800 ± 620 | 2380 ± 510 |

| 13 | H | NH(CH2)2φ(CH2)2CONH-(CH2)2NH2* | 305 ± 59 | 2550 ± 460 | 850 ± 202 | 7260 ± 1800 |

| 14 | H | NH(CH2)2φ(CH2)2CO2CH3* | 682 ± 258 | 1050 ± 300 | 1640 ± 380 | 1300 ± 220 |

| 15 | φSO3H* | H | 342 ± 107 | 4090 ± 1850 | 2910 ± 480 | 1100 ± 380 |

| 16 | φCH2CONH-φCH2CONH-(CH2)2NH2* | H | 408 ± 138 | 4000 ± 850 | 1630 ± 280 | 2600 ± 400 |

Structures given in Figure 1. All of the compounds are nucleoside derivatives except for the triazoloquinazoline 2, a potent and non-selective AR antagonist. Compounds 2–4, 10, 12, and 16 were reported to be full agonists at the A3AR. Compounds 5–7, 9, and 11 only partially activated the A3AR at 10 μM, and compound 8 was shown to be an A3AR antagonist.[9,13,14,20]

Data represents Ki ± standard error of mean. Ki values are obtained from competition binding assays in the presence of 125I-AB-MECA using the Cheng-Prusoff equation.[19] All experiments were performed 3 times independently and averaged.

φ = Phenyl group (all para-substituted).

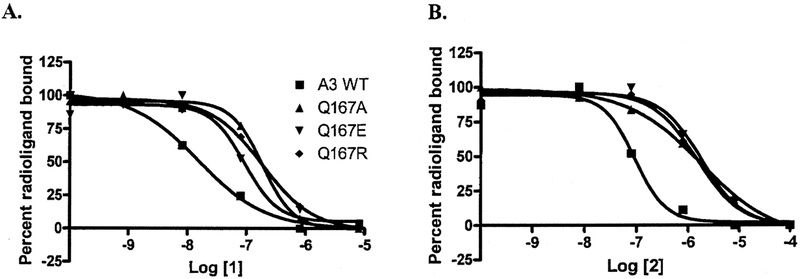

The nonselective agonist 2, which lacks a 2-position substituent but bears a 5′-N-ethyl uronamide moiety, exhibited reduced affinity at all the mutant receptors (Figure 2A). Reduced affinity was also observed for the triazoloquinazoline antagonist, 1 (Figure 2B). Despite the distinct steric and electrostatic properties of the 3 mutant side chains, the affinity of each of these compounds was shown to be similar at all three mutant receptors. Thus, a reduction in affinity of roughly 20-fold for 2 and 10-fold for 1 was observed at all mutant receptors.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of specific binding of 125I-I-AB-MECA by known nonselective antagonist (1) and agonist (2). All compounds were tested three times independently. Their Ki values, averaged from 3 independent experiments, are listed in Table 1. Graphs shown are from a single experiment representative of at least 3 experiments of similar results.

Effects of 2-Substituted Long-chain Adenosine Derivatives

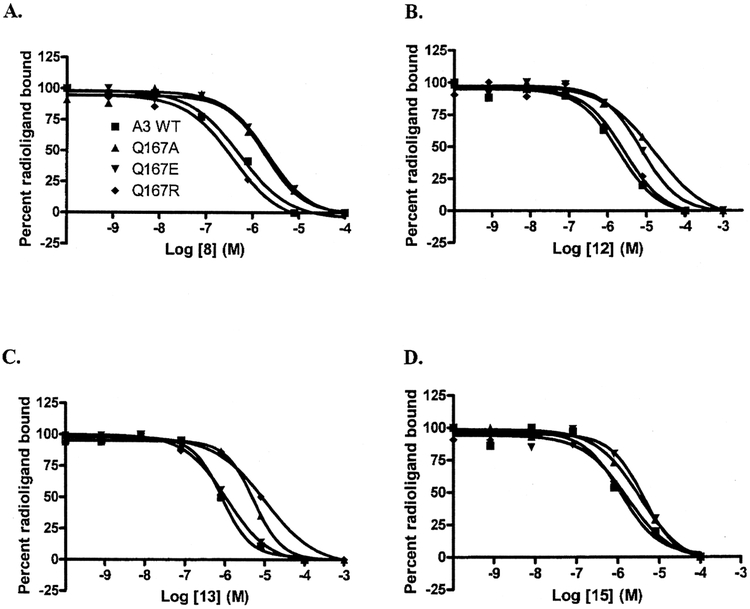

Compounds derived from the potent A2AAR agonist, 12, were tested at the WT A3AR and at the Q167 mutant receptors. These compounds share the 5′-N-ethyl uronamide group with 2 but also contain a sterically bulky substituent at the 2-position terminating in either a carboxylic acid, the corresponding methyl ester, or a positively-charged aminoethyl amide group. 12, containing the negatively-charged carboxylate derivative, exhibited a 3.6-fold decrease in affinity at the Q167R mutant receptor in comparison to the wild type (Figure 3B). However the decrease in affinity of 12 at the other mutant receptors was more pronounced. Compared to the Q167R mutant receptor, the Q167E mutant receptor showed an additional 2.4-fold decrease in affinity, and the alanine mutant, a 3.4-fold further decrease. These values correspond to 8.7 and 12-fold decreases in affinity compared to WT A3AR, respectively. In contrast, the positively-charged derivative 13, although 2.8 times weaker at the Q167E mutant receptor than at WT, showed enhancement at that mutant receptor in comparison to the alanine and arginine variants (Figure 3C). The affinity of 13 was increased 3 and 8.5-fold at the Q167E mutant receptor in comparison to the Q167A and Q167R mutant receptors, respectively. The uncharged methyl ester derivative CGS 23058, 14, had a similar affinity for all three mutant receptors.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of specific binding of 125I-I-AB-MECA by adenosine derivatives displaying differential affinity at mutant receptors. All compounds were tested three times independently. Their Ki values averaged from 3 independent experiments are listed in Table 1. Graphs shown are from a single experiment representative of at least 3 experiments of similar results

Effects of N6-Substituted Derivatives

The effect on affinity of appending a charged group to the N6 position was also investigated. The negatively-charged sulfophenyl-containing compound 15 showed a 2.6 and 3.7-fold decrease in affinity at Q167E and Q167A, respectively, when compared to the positively-charged Q167R mutant receptor (Figure 3D). In contrast, the positively charged 16 did not show a pronounced enhancement at the Q167E mutant receptor, with a less than 2-fold gain in affinity when compared to the Q167R mutant receptor and a roughly 2.5-fold gain in comparison to the Q167A. 16 also showed a 4-fold decrease in affinity at Q167E as compared to the wild-type receptor.

Recently Synthesized Adenosine Derivatives

Compounds 4-6, 8-9, and 11 were originally synthesized as derivatives of the potent A3 agonists 3, 7 (a partial agonist), and 10, respectively.[13] These modifications were previously used to assess the effect of 2-position substitutions on modulating adenosine receptor affinity and efficacy.[13]

At the wild type A3AR, the N6-methyl substituted compounds (3-6) displayed a loss of affinity that appeared to be correlated to the size of the substituent. Thus, in order of decreasing affinity, 3 > 4 > 5 > 6. This rank order of affinity was preserved in each of the mutant receptors, although compounds displayed a decrease in affinity at the mutant receptors in relation to the wild type. There was not a substantial difference in affinities of individual compounds across different mutant receptors, despite the chemical diversity of the different mutations at position 167.

The C2 unsubstituted agonist 10 displayed high affinity at both the wild type and mutant receptors, displaying slightly greater affinity at the wild type A3AR versus the Q167 mutant receptors. 11, the 2-carboxylate derivative of 10, also showed higher affinity at the wild type AR in comparison to the mutant receptors, but the addition of the 2-carboxylate group dramatically decreased affinity at mutant and wild-type receptors.

The series of N6-5-chloro-2-methoxy-benzyl compounds (7-9) displayed reduced affinity at mutant receptors compared to wild type. The negatively-charged 8 displayed a preference for the Q167R receptor and, among the three mutant receptors, displayed the weakest affinity for the Q167E mutant receptor (Figure 3A). Substitution of the 2-carboxylate group of 8 with the methyl ester moiety of 9 did not produce a similar effect, suggesting that the charge on the C2 moiety is important for this enhancement.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to use a neoceptor approach to detect ligand-receptor interactions between adenine-substituted adenosine derivatives and Gln167 of the A3AR. The effects of substitution of adenosine at N6 and C2 positions on affinity and intrinsic efficacy at the wild type A3AR have been studied extensively.[13,14,20] Here, Gln167 was systematically mutated to the approximately isosteric, but negatively charged glutamate, the positively-charged arginine, and alanine in order to cover a range of possible ligand-receptor interactions. No compound displayed enhanced affinity at any mutant receptor over the wild type receptor. However, some compounds displayed a preferential selectivity for one mutant receptor over the others, indicative of charge complementarity in a GPCR binding site.[15, 21] The negatively-charged 12 displayed enhanced binding at the Q167R mutant receptor in comparison with the others. Furthermore, 13, structurally similar to 12, but bearing a positively-charged moiety at the C2 position, demonstrated an affinity enhancement at the negatively-charged Q167E mutant receptor. Lastly, the uncharged methyl ester derivative, 14, displayed no affinity preference for any mutant receptor. This suggests that the C2 position of compounds derived from 12 as a scaffold may be in proximity to the residue at position 167 when bound to a receptor mutated at that position.

In all, four compounds demonstrated a preference for one of the charged mutant receptors over the other mutant receptors. The instances of enhancement involved ligands that carried a charge opposite to the charge on the mutated residue. There were no instances where any compounds tested displayed an enhanced affinity at the alanine mutant versus the charged mutant receptors. Additionally, each of the uncharged ligands (1-4, 7, 9, 10, and 14) displayed similar affinities across all mutant receptors. This suggests that charge complementation may have been a factor in the energetics of binding between some ligands and mutant receptors, dependent on a precise geometry in the binding site.

Although there was evidence for direct contact between the C2 moiety and residue 167 of the mutant receptor for the long chain adenosine derivatives, this was not as clear for ligands bearing smaller C2 substituents. For compounds 3-11, only 8 displayed any marked affinity preference for a particular mutant receptor. Furthermore, 15, which bears a negatively-charged group at the N6 position, and not C2, slightly favored binding at the Q167R mutant. Because of the diverse nature of the ligands tested, different nucleoside binding modes may exist. Furthermore, introduction of a mutated residue itself can lead to local conformational changes in the receptor binding site, possibly altering the mode of binding.

Nevertheless, our evidence suggests the importance of Gln167 and, consequently, that of the second extracellular loop in ligand binding, since all mutant receptors displayed reduced ligand affinity. 12 was enhanced at Q167R relative to other mutant receptors and 13 was enhanced at Q167E, consistent with electrostatic attraction between the mutated side amino acid chain and the extended 2-position substituent of each ligand.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michihiro Ohno for synthesizing several of the adenosine derivatives used in this study. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fredholm BB; Jzerman AP; Jacobson KA; Klotz KN; and Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacological Reviews 2001, 53, 527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knutsen LJ; Lau J; Petersen H; Thomsen C; Weis JU; Shalmi M; Judge ME; Hansen AJ; Sheardown MJ N-substituted adenosines as novel neuroprotective A1 agonists with diminished hypotensive effects. J. Med. Chem 1999, 42, 3463–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okusa MD; Linden J; Huang L; Rieger JM; Macdonald TL; Huynh LP A2A adenosine receptor-mediated inhibition of renal injury and neutrophil adhesion. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol 2000, 279, F809–F818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohta A; Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature 2001, 414, 916–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang BT; Jacobson KA A physiological role of the adenosine A3 receptor: Sustained cardioprotection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1998, 95, 6995–6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Lubitz DKJE; Lin RCS; Popik P; Carter MF; Jacobson KA Adenosine A3 receptor stimulation and cerebral ischemia. Eur J. Pharmacol 1994, 263, 59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman P; Madi L; Bar-Yehuda S; Barer F; Del Valle L; Khalili K. Evidence for involvement of Wnt signaling pathway in IB-MECA mediated suppression of melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2002, 21, 4060–4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T; Hori T; Behnke CA; Motoshima H; Fox BA; Le Trong I; Teller DC; Okada T; Stenkamp TE; Yamamoto M; Miyano M. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 2000, 289, 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao ZG; Kim SK; Biadatti T; Chen W; Lee K; Barak D; Kim SG; Johnson CR; Jacobson KA Structural determinants of A3 adenosine receptor activation: Nucleoside ligands at the agonist/antagonist boundary. J. Med. Chem 2002, 45, 4471–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J;Jiang Q; Glashofer M; Yehle S; Wess J; Jacobson KA Glutamate residues in the second extracellular loop of the human A2A adenosine receptors are required for ligand recognition. Mol. Pharmacol 1996, 49, 683–691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moro S; Hoffmann C; Jacobson KA Role of the extracellular loops of G protein-coupled receptors in ligand recognition: A molecular modeling study of the human P2Y1 receptor. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 3498–3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao ZG; Chen A; Barak D; Kim SK; Muller CE; Jacobson KA Identification by site-directed mutagenesis of residues involved in ligand recognition and activation of the human A3 adenosine receptor. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 19056–19063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohno M; Gao ZG; van Rompaey P; Tchilibon S; Kim SK; Harris BA; Blaustein J; Gross AS; Duong HT; van Calenbergh S; Jacobson KA Modulation of adenosine receptor affinity and intrinsic efficacy in nucleosides substituted at the 2-position. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2004, 12, 2995–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao ZG; Mamedova LK; Chen P; Jacobson KA 2-substituted adenosine derivatives: Affinity and efficacy at four subtypes of human adenosine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol 2004, 68, 1985–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson KA; Gao ZG; Chen A; Barak D; Kim SA; Lee K; Link A; van Rompaey P; van Calenbergh S; Liang BT Neoceptor concept based on molecular complementarity in GPCRs: A mutant adenosine A3 receptor with selectively enhanced affinity for amine-modified nucleosides. J. Med. Chem 2001, 44, 4125–4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SK; Gao Z-G; van Rompaey P; Gross AS; Chen A; Van Calenbergh S; Jacobson KA Modeling the adenosine receptors: Comparison of binding domains of A2A agonist and antagonist. J. Med. Chem 2003, 46, 4847–4859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olah ME; Jacobson KA; Stiles GL Role of the second extracellular loop of adenosine receptors in agonist and antagonist binding: Analysis of chimeric A1/A3 adenosine receptors. J. Biol. Chem 1994, 269, 24692–24698. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradford MM A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng YC; Prusoff WH Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol 1973, 22, 3099–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao ZG; Blaustein J; Gross AS; Melman N; Jacobson KA N6-Substituted adenosine derivatives: Selectivity, efficacy, and species differences at A3 adenosine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol 2003, 65, 1675–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strader CD; Gaffney T; Sugg EE; Candelore MR; Keys R; Patchett AA; Dixon RA Allele-specific activation of genetically engineered receptors. J. Biol. Chem 1991, 266, 5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]