Abstract

Objective

To quantify the missed opportunities for epilepsy surgery referral and operationalize the Canadian Appropriateness of Epilepsy Surgery (CASES) tool for use in a lower income country without neurologists.

Methods

People with epilepsy were recruited from the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital from 2014–2016. Each participant was clinically evaluated, underwent at least one standard EEG, and was invited to undergo a free 1.5 Tesla brain MRI. Clinical variables required for CASES were operationalized for use in lower-income populations and entered into the free, anonymous website tool.

Findings

There were 209 eligible participants (mean age 28.4 years, 56% female, 179 with brain MRI data). Of the 179 participants with brain MRI, 43 (24.0%) were appropriate for an epilepsy surgery referral, 21 (11.7%) were uncertain, and 115 (64.3%) were inappropriate for referral. Among the 43 appropriate referral cases, 36 (83.7%) were “very high” and 7 (16.3%) were “high” priorities for referral. For every unit increase in surgical appropriateness, quality of life (QoL) dropped by 2.3 points (p-value <0.001). Among the 68 patients who took >1 antiepileptic drug prior to enrollment, 42 (61.8%) were appropriate referrals, 14 (20.6%) were uncertain, and 12 (17.6%) were inappropriate.

Conclusion

Approximately a quarter of Bhutanese epilepsy patients who completed evaluation in this national referral-based hospital should have been evaluated for epilepsy surgery, sometimes urgently. Surgical services for epilepsy are an emerging priority for improving global epilepsy care and should be scaled up through international partnerships and clinician support algorithms like CASES to avoid missed opportunities.

Keywords: Asia, epilepsy, health services, mental health, quality of life, seizures, surgical services

1. Introduction

Nearly 80% of people with epilepsy (PWE) live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and up to 70% of PWE could become seizure-free if diagnosed and treated properly (World Health Organization 2019). However, a systematic review found that the treatment gap for epilepsy exceeds 75% in low-income countries and 50% in middle-income countries; this figure is projected to be higher in rural areas (Meyer et al. 2010). Some of the major contributors to the inadequate treatment of epilepsy in LMICs include the lack of expertise, stigma against epilepsy, cost of treatment, and the low availability of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) (Mbuba et al. 2008). Among LMICs, the average availability of AEDs in the public sector was below 50% and AED prices were multiple times higher than international reference prices, posing barriers to affordable and accessible epilepsy care (Cameron et al. 2012).

Randomized controlled trials of epilepsy surgery and retrospective studies of long-term surgical outcomes have demonstrated the effectiveness of epilepsy surgery for controlling seizures and improving the quality of life (QoL) of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (Wiebe et al. 2001; Seiam et al. 2011; Engel et al. 2012). Eliminating uncontrolled seizures through epilepsy surgery has been demonstrated to reduce mortality rates and risk of epilepsy-associated death, while providing substantial gains in life expectancy of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy (Sperling et al. 2005; Choi et al. 2008; Englot et al. 2014; Hennessy et al. 1999).

Despite the documented benefits of epilepsy surgery, however, surgical treatment is underutilized and delayed even in high-income and well-resourced countries (de Flon et al. 2010; Englot et al. 2012). A study of physician attitudes in Canada highlighted the knowledge gap that inhibits the rate of surgery referrals, with a substantial proportion of neurologists unable to identify the recommended standards of practice for epilepsy surgery referrals (Roberts et al. 2015). The Canadian Appropriateness of Epilepsy Surgery (CASES) algorithm, an online tool, was created to provide physicians with a systematic analysis of surgery referral appropriateness in accordance with accepted standards and guidelines (Jette et al. 2012).

Barriers to epilepsy surgery are usually even greater in LMICs due to the lack of organized care, health infrastructure, shortage of specialists, and the cost of surgery, which contribute to the underutilization of evidence-based surgical treatments (Watila et al. 2019). A global review conducted in 2000 found that only 26 of 142 LMICs conducted epilepsy surgery; despite advances in recent years, epilepsy surgery nevertheless remains a rare practice, making it difficult for PWE in LMICs to consider surgery as a viable treatment option (Watila et al. 2019; Weiser et al. 2000).

The significance of this research is to analyze a well-described cohort from Bhutan, a LMIC without a neurologist, with the primary objective of characterizing the missed opportunities for epilepsy surgery and the urgency of surgical treatments for this cohort using the CASES algorithm. Even if it were possible to extend the resources for epilepsy surgery to LMICs, there are currently no data on the impact that this would have on overall epilepsy treatment or the number of eligible patients who could potentially undergo surgery in these settings. As a secondary objective, we modify CASES, adjusting for various limitations that are more prominent in LMICs than high-income settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations and Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, USA, and the Research Ethics Board, convened by the Ministry of Health in Bhutan. Study participants provided written informed consent through a form administered in English or Dzongkha. A parent or next of kin provided consent for children or adult patients unable to provide their own consent. Children over the age of 14 years provided assent. Thumbprints were used in place of signatures for low-literacy patients.

2.2. Setting

The Kingdom of Bhutan is located in South Asia and had a reported population of 766,397 with a life expectancy of 71 years in 2018 (Central Intelligence Agency 2019). On the Human Development Index, a composite statistic of health, education, and income indicators, Bhutan ranks 134th out of 189 countries (United Nations Development Programme 2018). Bhutan had a gross national income per capita of 3,080 USD in 2018 and 8.2% of the population lives below the national poverty line (National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan 2017; World Bank 2019). The density of physicians, nurses, and midwives was 1.9 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2016, lower than the 4.45 health workers per 1,000 that the World Health Organization considers necessary to achieve coverage of primary healthcare needs (World Bank 2019; World Health Organization 2010). General healthcare in facilities is free and financed primarily by the government, supporting a total of 32 hospitals, 203 doctors, and 799 nurses nationwide (Adhikari 2016). Electroencephalogram (EEG) services became available in the capital city, Thimphu, in 2018. There is one neurosurgeon, but epilepsy surgery is not performed in Bhutan. Epilepsy cases of high complexity are occasionally referred to northern India; however, no epilepsy surgeries for Bhutanese patients are known to have occurred to date.

2.3. Recruitment and participants

Participants were identified at the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) in Thimphu. JDWNRH physicians began a registry of patients with epilepsy in 1999. Patients seen within the prior 7 years at the hospital were recruited through telephone invitations, posters, and word of mouth throughout 2014–2016. Potential participants were informed that the study would focus primarily on epilepsy and mobile EEG data collection. A person was eligible for enrollment if he/she (1) experienced two or more unprovoked, nonfebrile, epileptic seizures, i.e. met the International League Against Epilepsy’s (ILAE’s) definition of epilepsy, and (2) was able to provide consent or have consent provided by a next of kin proxy. Surgical appropriateness was not a consideration for participant recruitment as the CASES tool evaluates all patients with epilepsy. Participants were compensated with the Bhutanese equivalent of 10 USD for transportation costs.

2.4. Data Collection

Written surveys were administered in English or Dzongkha, depending on the participant’s preference, and administered by trained Bhutanese research coordinators. Data were collected on sociodemographic variables, seizure characteristics, medical history, epilepsy duration, and AED use. Each survey took approximately 45 minutes to complete and was performed in person at the JDWNRH. Participants also completed the Quality of Life in Epilepsy survey instrument (QOLIE-31) developed by RAND Healthcare, which was used to quantify quality of life with scores ranging from 0 (lowest QoL) to 100 points (highest QoL) (RAND Healthcare 2019). Each participant underwent at least one 30-minute xltekTM EEG by a U.S. or Canadian certified technician and was invited to undergo a 1.5 Tesla brain MRI at the JDWNRH at a future date. EEGs and MRIs were interpreted by North American-based neurologists. Patients who had complete clinical data and at least one EEG were included; brain MRI is not required for CASES (Jette et al. 2012).

2.5. The CASES Algorithm

The CASES algorithm, an evidence-based tool, was created by expert panelists from Canada and the USA who evaluated 2,646 clinical scenarios and provided the foundation for an online tool for neurologists and other healthcare providers (found at toolsforepilepsy.com). The resulting output presents an expert consensus score based on the ways in which panelists evaluated a particular combination of patient variables.

CASES is most appropriate for patients over 12 years of age with focal epilepsy (Jette et al. 2012). The tool asks a series of questions on eight main epilepsy-related factors including seizure semiology, epilepsy duration, seizure frequency, seizure severity, use of AEDs, AED side effects, EEG results, and MRI results (Jette et al. 2012). CASES classifies a patient on a scale of 1 to 9, with a score from 1–3 being deemed “inappropriate” for referral, a score from 4–6 deemed “uncertain” and a “strong consideration” for referral, and a score from 7–9 deemed a “definite need” for referral. For “definite need” patients, the tool also provides a priority score on a scale of 1 to 9, with a score from 1–3 indicating “moderate priority,” a score from 4–6 indicating “high priority,” and a score from 7–9 indicating “very high priority.” These priority scores have also been determined by consensus within the expert panel. CASES has subsequently been validated in other high-income settings such as Sweden, where a population-based study demonstrated that the tool is highly sensitive and accurate (Lukmanji et al. 2018).

2.6. Operationalization of Variables

Table 1 includes the variables used by CASES and the operationalization of these variables for the Bhutanese cohort. Many variables were straightforward to adapt as they were quantitative measurements. Others required specific adaptations due to data constraints present in the LMIC setting. Notably, the seizure type variable is divided into focal aware and impaired awareness seizures by the CASES tool but was operationalized by a survey question on loss of consciousness.

Table 1.

Original/Adapted Variables of the CASES Algorithm

| Original Variables | Adapted Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Seizure Type | 1. Focal aware seizures (consciousness not impaired) 2. Focal impaired awareness seizures (consciousness impaired) |

Seizure type adapted to a “loss of consciousness versus no loss of consciousness” category among patients with known seizures |

| Epilepsy Duration | 1. <1 year 2. >1 year |

Epilepsy duration calculated by subtracting “age at first seizure (years)” survey question from “age (years)” question |

| Seizure Frequency | 1. Seizure-free 2. <1 seizure/year 3. 1–12 seizures/year 4. ≥1 seizure/month |

“Number of seizures/month” and “last seizure” questions synthesized to construct best estimates for seizure frequency |

| Seizure Severity | 1. Non-disabling 2. Disabling • Injuries, significant medical problems, psychosocial consequences |

Questions on seizure-induced injuries and participant response from stigma surveys synthesized to create an assessment of seizure severity |

| Use of AEDs | 1. 0 AEDs tried 2. 1 3. 2 4. ≥ 3 |

Number and types of AEDs recorded by survey questions and directly matched to this category |

| Side Effects | 1. No 2. Yes |

Any unintended side effects were deemed valid for the purpose of the algorithm. “Side effects” survey question matched directly to this category |

| EEG Results | 1. Normal 2. Abnormal 3. Unavailable |

Data for two stationary EEG readings and one smartphone EEG reading adapted to construct normality decisions |

| MRI Results | 1. Normal 2. Abnormal • Abnormal if epileptogenic lesions are detected 3. Unavailable |

MRIs completed using an epilepsy-specific protocol matched directly to this category |

Seizure severity was a particularly subjective variable, described by the CASES tool authors as including “injuries, significant medical problems, and psychosocial consequences” (Jette et al. 2012). The Bhutanese survey collected information on self-reported burns, bone fractures and joint dislocations, head injuries, car accidents, and other seizure-associated injuries. Moreover, stigma surveys collected information on “difficulties in daily life” and the “extent of prejudice” that patients faced in categories including relationships, marriage, work, schooling, and general life. Every patient who indicated a strong level of difficulty in their life due to seizure injuries and/or prejudice with a rating of 4 or higher (on a 5-point scale) was deemed to have a disabling seizure. The remaining variables were operationalized using carefully-chosen survey responses from the Bhutanese cohort.

2.7. Data Analysis

Each participant’s data were anonymously entered into the CASES online appropriateness tool for epilepsy surgery evaluation. Patients with no brain MRI data were analyzed separately to determine if they differed in some way from those who did have an MRI. Statistical analyses were done using R and Excel.

Patients were also stratified by their lifetime reported AED history into (1) those patients who tried more than 1 AED in their lifetime and (2) those who tried 1 or none. This division was chosen as the CASES algorithm overwhelmingly designates patients who have taken ≤1 AED as low surgery priorities regardless of other variables (Jette et al. 2012).

2.8. Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available to qualified investigators by the authors upon reasonable request.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Eligibility and Subcohorts

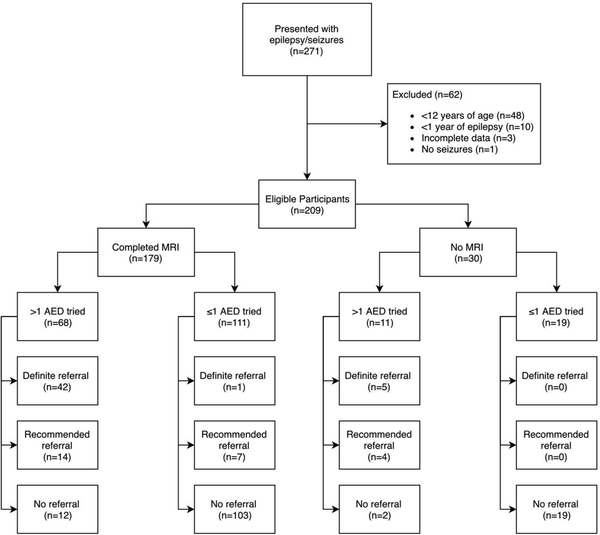

There were 271 total participants in the Bhutanese epilepsy cohort at the time of this study, of whom 209 were eligible for this analysis [Figure 1]. Excluded patients were 1 patient with a diagnosis other than epilepsy determined after enrollment, 48 children under 12 years old at the time of evaluation, 3 adults with epilepsy but incomplete data making CASES algorithm use impossible, and 10 adults who had new-onset epilepsy with a duration of less than 1 year. MRI data were available for 179 of the participants.

Figure 1. Participant Eligibility from the Bhutan Epilepsy Project for the CASES Analysis.

Participant eligibility from the Bhutan Epilepsy Project for CASES Analysis. Flowchart depicts the determination process for final eligible cohort (n=209). Eligible cohort was divided first by availability of MRI data, then by antiepileptic drug (AED) usage. Referral breakdowns are presented for each category.

*AED = Antiepileptic drug

3.2. Participant Characteristics

The cohort studied was relatively uneducated and unemployed compared to national averages and suffered from a high seizure burden [Table 2]. The majority (54%) of patients completed a maximum of primary education or no formal schooling and 45% completed secondary education, trailing the national secondary school enrollment rate of 66% (World Bank 2019). Approximately one-third of the cohort (35%) was unemployed, significantly higher than the national unemployment rate of 2.2% (World Bank 2019).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Sex (n=209) | ||

| Male | 92 | 44 |

| Female | 117 | 56 |

| Age (n=209) | ||

| <30 years | 141 | 68 |

| 31–50 years | 57 | 27 |

| >50 years | 11 | 5 |

| Education (n=209) | ||

| None | 50 | 24 |

| Elementary School | 63 | 30 |

| Middle School | 33 | 16 |

| High School | 38 | 18 |

| College | 22 | 11 |

| Other1 | 3 | 1 |

| Employment Status (n=196) | ||

| Unemployed | 68 | 35 |

| Farmer | 25 | 13 |

| Student | 38 | 19 |

| Business/Tech | 34 | 17 |

| Government | 12 | 6 |

| Educator | 6 | 3 |

| Religious | 11 | 6 |

| Healthcare | 2 | 1 |

| Residence by District (n=208) | ||

| Thimphu (contains capital city) | 20 | 10 |

| Bumthang | 4 | 2 |

| Chukha | 10 | 5 |

| Dagana | 11 | 5 |

| Gasa | 2 | 1 |

| Haa | 7 | 3 |

| Lhuntse | 6 | 3 |

| Mongar | 6 | 3 |

| Paro | 22 | 11 |

| Pemagatshel | 5 | 2 |

| Punakha | 10 | 5 |

| Samdrup Jongkhar | 11 | 5 |

| Samtse | 13 | 6 |

| Sarpang | 16 | 8 |

| Trashigang | 15 | 7 |

| Trashiyangtse | 12 | 6 |

| Trongsa | 4 | 2 |

| Tsirang | 15 | 7 |

| Wangdue Phodrang | 15 | 7 |

| Zhemgang | 4 | 2 |

| Seizure Characteristics | ||

| Seizure Frequency (n=209) | ||

| Seizure-free | 44 | 21 |

| <1 seizure/y | 40 | 19 |

| 1–12 seizures/y | 48 | 23 |

| ≥1 seizure/mo | 77 | 37 |

| Seizure Type (n=209) | ||

| No loss of consciousness | 58 | 28 |

| Loss of consciousness | 151 | 72 |

| Seizure Severity (n=209) | ||

| Nondisabling | 67 | 32 |

| Disabling | 142 | 68 |

| AED Side Effects (n=209)2 | ||

| Yes | 60 | 29 |

| No | 149 | 71 |

| MRI Evaluation (n=179) | ||

| Normal | 41 | 23 |

| Abnormal | 138 | 77 |

| EEG Evaluation (n=209) | ||

| Normal | 129 | 62 |

| Abnormal | 80 | 38 |

| AED Use (n=209) | ||

| 0 | 5 | 2 |

| 1 | 125 | 60 |

| 2 | 56 | 27 |

| 3+ | 23 | 11 |

| MRI Abnormalities (n=138) | ||

| Mesial Temporal Sclerosis (MTS) | 86 | 62 |

| Neurocysticercosis (NCC) | 18 | 13 |

| MTS + NCC | 6 | 4 |

| Stroke | 6 | 4 |

| Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) | 4 | 3 |

| Other3 | 18 | 14 |

2 participants attended a school of disability and 1 attended a religious school.

Reported side effects include: headaches, memory loss, depression, anxiety, weakness, emotional instability, drowsiness, body pain, and digestive problems, among others.

Other abnormalities include: cortical lesions, schizencephaly, cystic encephalomalacia, R occipital gliosis, trauma, cavernoma, and R frontal cystic encephalomalacia.

Nearly 40% of all patients experienced more than 1 seizure per month, the highest frequency category described by CASES. Many (72.3%) experienced loss of consciousness during their seizures. Most patients (67.9%) also experienced disabling seizures. Of these, a sizeable proportion (88.7%) reported being affected by psychosocial consequences such as epilepsy-associated stigma or prejudice, 44.4% reported seizure-associated injuries, and 33.1% reported a combination of both. Of the 179 patients who received an MRI, a significant number (77.1%) had a clinically relevant brain abnormality (Table 2). Patients who had not received an MRI were included in the study, with the understanding that the results of the CASES algorithm are less reliable when imaging is not available. Such patients were analyzed separately from the cohort of patients who received an MRI.

Despite the high seizure burden, AED use was limited. Most patients (62.2%) had not taken more than 1 AED, 26.8% had tried 2 AEDs, and 11% had tried more than 2 AEDs. Patients who were not drug-resistant were nevertheless included in the study. Pre-screening epilepsy patients based on surgical criteria would defeat the purpose of the CASES tool, which is to disqualify such patients. This is especially valuable in resource-limited settings that have a lack of physicians with expertise in epilepsy.

3.3. CASES Tool Results

From the >1 AED subcohort (n=68), 61.8% (n=42) were designated by the CASES tool as definite surgery referrals, 20.6% (n=14) were uncertain cases and strongly recommended for referral, and 17.6% (n=12) were deemed inappropriate for referral [Figure 1]. From the ≤1 AED cohort (n=111), 0.9% (n=1) were definite referrals, 6.3% (n=7) were strong recommendations, and 92.8% (n=103) were deemed inappropriate.

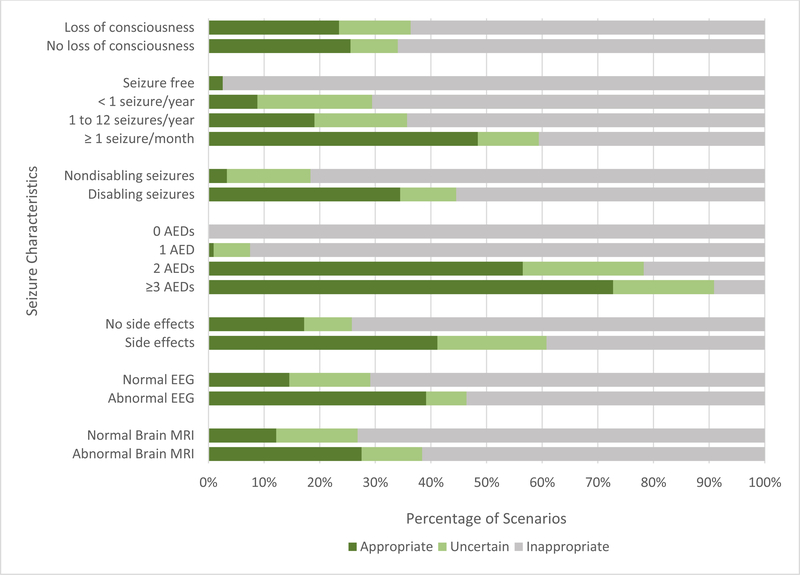

In total, combining both groups (n=179) revealed 24.0% (n=43) of the cohort as definite referrals, 11.7% (n=21) as strong recommendations, and 64.3% (n=115) as inappropriate for referral. Of all patients classified as definite referrals, 83.7% (n=36) would be considered “very high” priority for referral and 16.3% (n=7) were “high” priorities, with no “moderate” priorities. Appropriateness scores were impacted by individual CASES variables to varying degrees [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Appropriateness Breakdown by CASES Variable.

Appropriateness breakdown by CASES variable. For each variable, the bars represent the proportion of patients with a specific clinical characteristic who are appropriate (dark green), uncertain (light green), and inappropriate cases for referral (gray). Comparisons between bars within each variable allows for an understanding of how changes in a particular variable affect the referral diagnosis.

3.4. Subgroup Analyses

From the no MRI cohort (n=30), of the 11 patients who had tried >1 AED, 45.5% (n=5) were designated as definite referrals, 36.4% (n=4) as uncertain, and 18.2% (n=2) as inappropriate for referral. From the ≤1 AED subgroup (n=19), every patient was deemed inappropriate. In total, 16.7% (n=5) were definite referrals, 13.3% (n=4) were uncertain, and 70% (n=21) were inappropriate for referral. Of the definite referrals, 40% (n=2) were considered “very high” priority and 60% (n=3) were “high” priorities, with no “moderate” priorities.

3.5. Quality of Life in Epilepsy and Surgical Referral

QoL was analyzed by CASES referral category for patients with MRI data (n=179). 4 of 115 patients from the inappropriate group and 2 of 43 patients from the definite referral group did not complete the QoL survey. The inappropriate referral group rated their QoL at a mean of 59.6 points (standard deviation (SD): 16.5), the uncertain group 53.3 points (SD: 15.3), and the definite referral group 44.6 points (SD: 16.1). While the inappropriate and uncertain groups had above-average QoL scores compared to the average QoL for Bhutanese PWE in general (48.9, SD: 16.7), the definite referral group reported below average QoL scores (Saadi et al. 2016).

As the appropriateness for surgery referral increased in priority, QoL scores concomitantly decreased. For every unit increase in surgical priority from 1 to 9, QoL dropped by 2.3 points (p-value <0.001). Overall, there was a 25.2% QoL score decrease from the inappropriate to definite surgical referral groups.

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis for the No or One AED Group

To gain an understanding of how the ≤1 AED cohort (with MRI data) would look with increased AED accessibility in this low availability environment, these 111 patients were entered into the CASES tool a second time, but with the “AEDs tried” category modified to 2 AEDs for each patient. The other seizure characteristics were kept constant for this exercise. Overall, the simulation was expected to overestimate the proportion of definite referrals as the additional AED taken by the patients, if effective, would theoretically reduce some seizure characteristics such as frequency and severity but simultaneously underestimate the number of side effects patients experienced that could arise from the use of an additional AED. While the simulation was subject to such assumptions, we felt that the sensitivity analysis could help project the impact of improved epilepsy care and AED accessibility on future eligibility for surgery. We also knew from the CASES tool results that 62% of patients in the cohort who took more than 1 AED still displayed seizure characteristics that warranted a surgery referral, and it was reasonable to expect that the ≤1 AED cohort may not deviate considerably in its response to an additional AED trial.

The sensitivity analysis found that had the 111 patients tried one more AED, 47 more would become definite referrals (total 48, 43.2%) for epilepsy surgery and 11 more (total 18, 16.2%) would become strong recommendations. Although there was a clear increase in surgery-appropriate patients as a result of the simulation, the overall proportions of appropriateness reflected fewer definite referrals than was observed in the actual >1 AED cohort. This effect was expected as some of the patients who only tried 1 AED did so because they achieved seizure control with that one medication. With this simulated AED increase, approximately half of the total cohort (90 from 179) would be definite surgery referrals.

4. Discussion

A significant proportion of Bhutanese PWE experience missed opportunities for epilepsy surgery referrals, and this number could rise as AED prescribing improves throughout the country. Notably, among these missed opportunities, we found that a high percentage (83.7%) were considered “very high” priorities for epilepsy surgery referral, reinforcing the immediacy of the situation for PWE in Bhutan. Bhutan is unusual among LMICs in that it has a public health care system which does not require any out of pocket payments by patients for medications or health services (Adhikari et al. 2016). However, services for epilepsy including drug procurement, ancillary tests, and expertise are extremely limited (McKenzie et al. 2016). As such, in spite of limited patient costs, Bhutan likely reflects the situation in many other LMICs with a similar lack of neurological and neurosurgical resources. It also reflects a situation that many lowest-income countries could find themselves in if neurological expertise remains absent in the future.

We applied the CASES algorithm to a well-characterized cohort of PWE in a lower-income setting without neurologists, and extended its utility to a more rural population of patients with overall limited formal education, high stigma, and a restricted selection of AEDs. The overall breakdown of referral categories in Bhutan (24.0% definite, 11.7% uncertain, 64.3% inappropriate) was relatively similar to that of the Canadian population originally evaluated by CASES (20.6%, 17.2%, 61.5%, respectively), emphasizing the applicability of the CASES algorithm and operationalized tool (Jette et al. 2012). Although neither country’s cohorts were population-based, they both provide an assessment of CASES in a relatively large and well-characterized group of PWE seen at referral centers in public health care systems.

We also propose adjustments to the CASES tool to improve its applicability for lower-income settings. The tool is strongly influenced by the number of AEDs taken by a patient—out of 2,646 scenarios evaluated originally by the tool, only 1 scenario in which patients had tried 1 AED or fewer was classified as appropriate for referral (Jette et al. 2012). In Bhutan and other LMICs, however, the tool should account for AED availability and access barriers that may not be as prominent in higher-income countries by accounting for a patient’s ability to take multiple AEDs. Moreover, although efforts were made to operationalize the CASES tool variables, some, such as seizure severity, did not provide objective criteria for determination. In well-resourced countries, neurologists can make reliable judgements on seizure severity upon patient consultation. However, in countries such as Bhutan, where primary care providers, traditional medicine practitioners, and psychiatrists are in charge of PWE, a clear set of criteria for variables that require such judgement may help improve the accuracy of the CASES tool.

Our study has several limitations. We did not conduct a population-based study and therefore our results do not reflect population-based prevalence estimates. Referral bias to the study is assumed. In some cases, patients with more manageable forms of epilepsy may not have chosen to participate in the study, and in others, patients with the worst seizure control or with the least access to healthcare may not have been able to travel to the hospital. We could not always determine seizure semiology from the Bhutanese cohort; rather, whether patients experienced a loss of consciousness during seizures was used to distinguish between some seizure types. This adjustment likely underestimated the proportion of complex partial seizures as complex partial seizures may only present as impairments of consciousness, which was not as well-captured in the data collected. Moreover, it is possible that AED diagnosis and use were not consistent with international standards, which would affect the determination of drug resistance for patients.

Despite these limitations, we provide comprehensive data to address a gap in the current literature on PWE in LMICs who experience missed opportunities for epilepsy surgery. In the Bhutan Epilepsy Project, brain MRI and multiple EEGs per participant were offered, which constitute better-than-usual care in this setting and most other lower-income countries. The quantitative output for CASES also allows for comparisons across settings for patients who are missing out on epilepsy surgery referrals and therefore, in many cases, epilepsy surgery and its benefits. We also provide evidence that the CASES priority score is inversely associated with QoL in epilepsy. In countries such as Bhutan, where stigma prevails, emergency services are challenging due to rough terrain, and accidental injuries are common, the benefits of epilepsy surgery may be even higher than they are in high-income settings where CASES has been implemented (McKenzie et al. 2016; Wibecan et al. 2018; Brizzi et al. 2016).

4.1. Conclusions

Initiatives to improve pathways and tools for epilepsy surgery referrals for non-neurologist specialists are likely to be valuable, potentially through collaboration with international partners in the region, such as Thailand, India, and Singapore. A referral pattern currently exists between Bhutan and India, where epilepsy surgery availability and infrastructure have improved significantly over the last two decades; epilepsy surgeries conducted throughout 39 state-level centers in India produce postoperative outcomes comparable to those from well- established centers in high-income countries today (Rathore et al. 2017). However, only 2 in every 1000 eligible patients in India undergo epilepsy surgery, suggesting that infrastructure and availability are not the only contributors to the surgical treatment gap (Rathore et al. 2017). An epidemiological review concluded that the success of epilepsy surgery programs in India and other LMICs depends partly on the ability to select ideal surgical candidates without compromising patient safety, a need that can potentially be fulfilled by the free and accessible CASES tool (Rathore et al. 2017). Efforts have been made in recent years to adapt CASES for patients in India (Malhotra et al. 2016).

With the average price of epilepsy surgery in India ranging from USD $1500 to $3400, any potential referrals may require an extension of Bhutan’s universal healthcare coverage plan to foreign hospital visits as well, with the Bhutanese government offsetting the cost of surgery instead of the individual patient (Watila et al. 2019). Such policies would require forward-thinking negotiations between relevant governments and ideally lead to capacity-building of Bhutanese health care workers to recognize, treat, and triage cases of epilepsy to the best available care.

Highlights.

24% of patients in a Bhutanese cohort were appropriate for epilepsy surgery referral

Surgical appropriateness and quality of life were inversely correlated in this cohort

84% of surgically appropriate patients were “very high” priorities for referral

No patient with epilepsy in Bhutan has yet to undergo epilepsy surgery

The CASES algorithm was adapted for future use in lower-income settings

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [grant number R21 NS098886]; and the Fogarty International Center [grant number R21 NS098886].

NJ receives grant funding paid to her institution for grants unrelated to this work from NINDS (NIH U24NS107201, NIH IU54NS100064), PCORI and Alberta Health. She also receives an honorarium for her work as an Associate Editor of Epilepsia.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement:

The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Adhikari D Healthcare and happiness in the Kingdom of Bhutan. Singapore Med J. 2016. March; 57(3): 107–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brizzi K, Deki S, Tshering L, Clark SJ, Nirola DK, Patenaude BN, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding epilepsy in the Kingdom of Bhutan. Int Health. 2016. July;8(4):286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cameron A, Bansal A, Dua T. Mapping the availability, price, and affordability of antiepileptic drugs in 46 countries. Epilepsia. 2012. June;53(6):962–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook: Bhutan. 2019. (Accessed 31 July 2019). https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bt.html

- [5].Choi H, Sell RL, Lenert L, Muennig P, Goodman RR, Gilliam FG, et al. Epilepsy surgery for pharmacoresistant temporal lobe epilepsy: a decision analysis. JAMA. 2008. December 3;300(21):2497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].de Flon P, Kumlien E, Reuterwall C, Mattsson P. Empirical evidence of underutilization of referrals for epilepsy surgery evaluation. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Engel J, McDermott MP, Wiebe S, Langfitt JT, Stern JM, Dewar S, et al. Early Surgical Therapy for Drug-Resistant Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2012. March 7; 307(9): 922–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Englot DJ, Ouyang D, Garcia PA, Barbaro NM, Chang EF. Epilepsy surgery trends in the United States, 1990–2008. Neurology. 2012. April 17; 78(16): 1200–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Englot DJ, Chang EF. Rates and predictors of seizure freedom in resective epilepsy surgery: an update. Neurosurg Rev. 2014. July; 37(3): 389–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hennessy MJ, Langan Y, Elwes RDC, Binnie CD, Polkey CE, Nashef L. A study of mortality after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 1999. October 12; 53(6): 1276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jette N, Quan H, Tellez-Zenteno JF, Macrodimitris S, Hader WJ, Sherman EM, et al. Development of an online tool to determine appropriateness for an epilepsy surgery evaluation. Neurology. 2012. September 11;79(11):1084–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lukmanji S, Altura KC, Rydenhag B, Malmgren K, Wiebe S, Jetté N. Accuracy of an online tool to assess appropriateness for an epilepsy surgery evaluation-A population-based Swedish study. Epilepsy Res. 2018. September;145:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Malhotra V, Chandra SP, Dash D, Garg A, Tripathi M, Bal CS, et al. A screening tool to identify surgical candidates with drug refractory epilepsy in a resource limited settings. Epilepsy Res. 2016. March;121:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mbuba CK, Ngugi AK, Newton CR, Carter JA. The epilepsy treatment gap in developing countries: a systematic review of the magnitude, causes and intervention strategies. Epilepsia. 2008. September; 49(9): 1491–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McKenzie ED, Nirola DK, Deki S, Tshering L, Patenaude B, Clark SJ, et al. Medication prescribing and patient-reported outcome measures in people with epilepsy in Bhutan. Epilepsy Behav. 2016. June;59:122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Meyer AC, Dua T, Ma J, Saxena S, Birbeck G. Global disparities in the epilepsy treatment gap: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2010. April 1; 88(4): 260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan. Bhutan Poverty Analysis Report 2017. 2017. (Accessed 31 July 2019). [Google Scholar]

- [18].RAND Healthcare. Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-89 and QOLIE-31). 2019. (Accessed 31 July 2019). https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/qolie.html

- [19].Rathore C, Radhakrishnan K. Epidemiology of epilepsy surgery in India. Neurol India. 2017;65(Supplement):S52–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Roberts JI, Hrazdil C, Wiebe S, Sauro K, Vautour M, Wiebe N, et al. Neurologists’ knowledge of and attitudes toward epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 2015. January 13;84(2):159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Saadi A, Patenaude B, Nirola DK, Deki S, Tshering L, Clark S, et al. Quality of life in epilepsy in Bhutan. Seizure. 2016. July;39:44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seiam AH, Dhaliwal H, Wiebe S. Determinants of quality of life after epilepsy surgery: systematic review and evidence summary. Epilepsy Behav. 2011. August;21(4):441–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sperling MR, Harris A, Nei M, Liporace JD, O’Connor MJ. Mortality after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2005;46 Suppl 11:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Indices and Indicators. 2018. (Accessed 31 July 2019). http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018_summary_human_development_statistical_update_en.pdf.

- [25].Watila MM, Xiao F, Keezer MR, Miserocchi A, Winkler AS, McEvoy AW, et al. Epilepsy surgery in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Epilepsy Behav. 2019. March;92:311–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wibecan L, Fink G, Tshering L, Bruno V, Patenaude B, Nirola DK, et al. The Economic Burden of Epilepsy in Bhutan. Trop Med Int Health. 2018. April; 23(4): 342–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001. August 2;345(5):311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wieser HG, Silfvenius H. Overview: Epilepsy Surgery in Developing Countries. Epilepsia. 2000;41 Suppl 4:S3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].World Bank. Bhutan. 2019. (Accessed 31 July 2019). https://data.worldbank.org/country/bhutan

- [30].World Health Organization. Epilepsy. 2019. (Accessed 31 July 2019). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy.

- [31].World Health Organization. Health workforce. 2010. (Accessed 31 July 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available to qualified investigators by the authors upon reasonable request.