To the Editor

Food allergy is associated with decreased quality of life and safety concerns among children and caregivers(1–4). Thirty-five to forty-five percent of children with food allergies report experiencing bullying(5, 6). Teasing about the food allergy by classmates at school is the most common experience, but criticism, waving and threatening with the food were also reported.(5) Children with food allergies were twice as likely to be bullied compared to children without food allergies.(6, 7) Allergists play an important role in the care of patients with food allergy with regard to helping them stay safe physically and emotionally. The percentages of allergists who recognize teasing/bullying as a problem among their food-allergic patients or the frequency with which allergists inquire about this are unknown. To address this, we developed and administered a survey about food allergy-related teasing/bullying to members of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI). The Institutional Review Board of Rochester Regional Health approved this study.

The survey (Figure E1) was administered electronically to a 20% random representative sample of US-based AAAAI physician members, emeritus members and fellows, fellows, and fellows-in-training. Response rate was 10.4% (N=98), which is on par with other AAAAI surveys administered in this fashion. Response rates for questions differed because not all respondents answered every question. There was no pattern to question response rate. In calculating percentages, we used appropriate numerators and denominators for independent questions. Demographics of respondents and all AAAAI members were compared by Pearson’s chi-squared test. Demographics were compared to survey responses by Pearson’s chi-squared test for gender and 1-way ANOVA for age and years since fellowship. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Median respondent age was 46.5 years (range 30.4–83.2) with 10.4 years (range 0–52.5) work experience in the field of allergy since completing fellowship. Respondents saw a median 10 children (range 0–60) with food allergies weekly. Of respondents, 92.7% (N=90/97) graduated from Allopathic medical schools and 10.3% (N=10/97) had more than one graduate degree. Residency training was 49.0% (N=47/96) Pediatrics, 42.7% (N=41/96) Internal Medicine, and 8.3% (N=8/96) Medicine-Pediatrics. Primary area of practice was 95.9% (N=94/98) Allergy, 2.0% (N=2/98) Immunology, 1.0% (N=1/98) Pulmonology, and 1.0% (N=1/98) retired from clinical practice. Respondents compared to all AAAAI members were more likely to be female (52.6% v. 40.1%, p=0.013), younger (61.1% v. 39.8% less than age 50, p<0.001), and more recently completed fellowship (65.6% v. 36.9% less than 16 years since completion p<0.001).

Of respondents, 63.2% (N=60/95) thought children with food allergy experienced more teasing/bullying than those without and 36.8% (35/95) did not think there was a difference. No respondents thought children with food allergy experienced less teasing/bullying compared to those without. Perceptions were not associated with respondent gender, age, or years post-fellowship.

Participants were asked with what frequency they ask patients and parents/guardians about teasing/bullying via three questions (Table I). A minority of respondents reported asking about teasing/bullying all of the time (7.3–8.3%), with most respondents asking about bullying some of the time (40.6–49.0%). A sizeable proportion of respondents (16.7–21.9%) never asked. Responses were not associated with participant gender, age, or years post-fellowship. Although almost half of respondents (42.7%, N=41/96) indicated they felt very comfortable asking about teasing/bullying, a similar proportion (42.7%, N=41/96) indicated they felt only somewhat comfortable addressing teasing/bullying (Table I). Increased comfort asking about teasing/bullying was associated with greater respondent age and years since fellowship completion but not gender (p=0.002, p=0.009 and p=0.475, respectively). Increased comfort addressing teasing/bullying was associated with greater respondent age but not years post-fellowship or gender (p=0.020, p=0.056 and p=0.684, respectively). Steps taken by providers to address teasing/bullying are summarized in Figure 1.

Table I. Asking about Teasing/Bullying in Pediatrics Patients with Food Allergy During Clinic Visits.

Number of respondents selecting a given answer (numerator), total number of people responding to question (denominator), and percentage of respondents selecting a given answer. Denominators differed, since not all respondents answered every survey question.

| All of tde time, % (N) | Some of the time, % (N) | Rarely, % (N) | Never, % (N) | ||

| Do you ask patients about teasing/bullying during your clinic visits? | 8.3% (8/96) | 49.0% (47/96) | 26.0% (25/96) | 16.7% (16/96) | |

| Do you ask parents/guardians whether their children experience teasing/bullying during your clinic visits? | 7.4% (7/94) | 45.7% (43/94) | 29.8% (28/94) | 17.0% (16/94) | |

| Do you ask patients whether they experience teasing/bullying during your clinic visits? | 7.3% (7/96) | 40.6% (39/96) | 30.2% (29/96) | 21.9% (21/96) | |

| Very comfortable, % (N) | Somewhat comfortable, % (N) | Neutral, % (N) | Somewhat uncomfortable, % (N) | Very uncomfortable, % (N) | |

| How comfortable do you feel asking parents/guardians and patients about teasing/bullying? | 42.7% (41/96) | 31.3% (30/96) | 19.8% (19/96) | 5.2% (5/96) | 1.0% (1/96) |

| How comfortable do you feel in helping patients and families appropriately address teasing/bullying concerns? | 21.9% (21/96) | 42.7% (41/96) | 14.6% (14/96) | 19.8% (19/96) | 1.0% (1/96) |

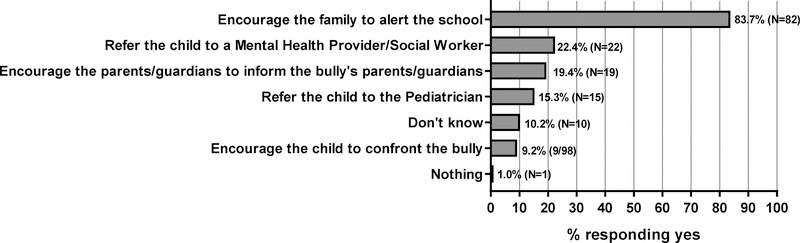

Figure 1: What do you typically do if you learn a patient is being teased/bullied due to food allergies?

Provider Actions when Learning a Pediatric Patient is Teased/Bullied due to Food Allergies. Respondents (N=95) could select more than one answer. Number and percentage of respondents selecting a given answer are indicated.

Barriers identified to asking patients/families about teasing/bullying were lack of time (42.1%, N=40/95), resources (25.3%, N=24/95), knowledge (12.6%, N=12/95), not thinking bullying is a problem (7.4%, N=7/95) and other (12.6%, N=12/95). Write-in answers supplied for “other” included: “didn’t know how to ask about it,” “unaware that it was a problem,” “bullying is not reported to me,” “do not think children with food allergies experience more bullying and rarely ask about it” and “the child must learn to handle these situations themselves or be handicapped as an adult.” Lack of time (39.6%, N=38/96), resources (18.8%, N=18/96) and knowledge (15.6%, N=15/96) were the most frequently cited barriers to being able to accurately identify which patients are victims of teasing/bullying and for being able to help patients/families appropriately address teasing/bullying concerns (29.8%, N=28/94; 30.9%, N=29/94 and 19.1%, N=18/94, respectively). Respondents cited resources on bullying (28.4%, N=27/95), more knowledge on the topic (24.2%, N=23/95), and handouts (15.8%, N=15/95) as being most helpful to facilitate asking about teasing/bullying.

Several limitations may limit the generalizability of our findings to a broader group of allergists or other providers. The survey utilized self-reporting, which could impact validity. Data from non-AAAAI members and non-US-based members is not represented. Our study focused on allergists’ approaches to bullying/teasing. Other healthcare providers, including primary care providers and advanced practice providers, also play important roles in managing patients with food allergies, and these providers may have different knowledge, comfort and approaches regarding teasing/bullying.

AAAAI members responding to the survey may not be representative of all members regarding approaches to teasing/bullying. Survey respondents were more likely to be female, younger, and more recently completed fellowship than the general AAAAI membership, which may impact responses. We found that greater provider age and years since fellowship completion were associated with increased comfort asking about and addressing teasing/bullying. While this suggests many providers may learn these skills in clinical practice, it also highlights an unmet need to teach these skills in the Allergy/Immunology fellowship curriculum.

This survey demonstrates that although some physicians are aware that bullying is a problem for food-allergic patients, a significant number are unaware. It also demonstrates the need for bullying-specific questions, education, and algorithms to assist in identifying and addressing teasing/bullying in children with food allergies. A study by Shemesh et al. showed that 48.9% of parents were unaware of bullying experienced by their food-allergic children.(5) As such, inquiring during the clinic visit using open-ended questions about peer experiences may allow discovery by the parent, enabling them to help their children, which has been associated with less distress and improved quality of life in bullied food-allergic children.(5) When bullying is discovered, it is most helpful for parents to notify the school, and this action was selected by the majority of respondents (83.7%, N=82/98).(8) The school can assess the situation, engage parents and students, institute interventions, support the child and monitor the situation.(9) Confrontation of the bully or his/her family, which were actions selected by 28.6% (N=28/98) of respondents, is not usually productive and should be discouraged.(6) Referral to a Mental Health Provider or Social Worker, although selected by 22.4% (N=22/98) of respondents, is not always needed, but should be considered when the child reports significant psychosocial distress (e.g., resistance to attending school, increased anxiety or depressed mood, increased somatic complaints like stomachaches or headaches, disinterest in typically enjoyed activities) and/or when the allergist feels ill-equipped to assist with the situation.(6) Suggestions and resources to help address bullying are listed in Table E1.

As the number of children with food allergy continues to rise, allergists and other healthcare providers will encounter a growing number of children who may be victims of teasing/bullying due to their food allergies. It is important for providers to be able to ask about, recognize, and provide guidance on management of teasing/bullying, since in many cases, not even the parents are aware that their child is being bullied. Additional training and resources are needed for allergists to be able to provide better care for their pediatric food-allergic patients who may be victims of teasing/bullying.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Implications.

Bullying is an issue for food-allergic patients. Allergists may benefit from education and resources to recognize and address this problem.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research is supported by NIH grant K24 AI 106822 (PI, Dr. Phipatanakul), The Allergy and Asthma Awareness Initiative, Inc (Dr. Phipatanakul) and NIH grant K23 AI143962-01 (PI, Dr. Bartnikas).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

M. C. Young is employed by South Shore Allergy and Asthma Specialists, PC and has received royalties from Quarto Publishing. S. H. Sicherer reports royalty payments from UpToDate and from Johns Hopkins University Press; grants to his institution from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, from Food Allergy Research and Education, and from HAL Allergy; and personal fees from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology as Deputy Editor of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, outside of the submitted work. W. Phipatanakul is a consultant advisory for Teva, Genentech, Novartis, GSK and Regeneron, for asthma-related therapeutics. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DunnGalvin A, Dubois AE, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Hourihane JO. The effects of food allergy on quality of life. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2015;101:235–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassenberg J, Cochard MM, Dunngalvin A, Ballabeni P, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Newman CJ, et al. Parent perceived quality of life is age-dependent in children with food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(5):412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flokstra-de Blok BM, van der Velde JL, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO, et al. Health-related quality of life of food allergic patients measured with generic and disease-specific questionnaires. Allergy. 2010;65(8):1031–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avery NJ, King RM, Knight S, Hourihane JO. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003;14(5):378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shemesh E, Annunziato RA, Ambrose MA, Ravid NL, Mullarkey C, Rubes M, et al. Child and parental reports of bullying in a consecutive sample of children with food allergy. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e10–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbert L, Shemesh E, Bender B. Clinical Management of Psychosocial Concerns Related to Food Allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(2):205–13; quiz 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieberman JA, Weiss C, Furlong TJ, Sicherer M, Sicherer SH. Bullying among pediatric patients with food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):282–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annunziato RA, Rubes M, Ambrose MA, Mullarkey C, Shemesh E, Sicherer SH. Longitudinal evaluation of food allergy-related bullying. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(5):639–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Support the Kids Involved. 2017. Available at: https://www.stopbullying.gov/respond/support-kids-involved/index.html. Accessed June 20, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.