Abstract

Background:

The effect of local treatment on survival in advanced-stage patients has gained interest in several malignancies; however, limited data exist regarding urothelial carcinoma (UC).

Objective:

To test the impact of surgery of the primary tumor site on cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and overall mortality (OM) in patients affected by metastatic UC.

Design, setting, and participants:

Individual patient-level data from a multicenter collaboration, including metastatic UC patients treated with first-line cisplatin- or carboplatin-based chemotherapy administered between January 2006 and January 2011 from hospitals in the USA, Europe, Israel, and Canada.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were used to assess the effect of surgery on CSM and OM in patients affected by metastatic UC using 3-mo landmark analyses. Subgroup analyses were performed on the basis of the number of metastasis sites involved and including only patients treated with surgery before the start of chemotherapy.

Results and limitations:

Of the 326 patients included in the study, 47 (14%) were treated with surgery of the primary tumor site. Median (interquartile range) follow-up was 43 (33–45) mo. Of the patients treated with surgery, 28 (60%) were affected by a primary bladder cancer and 19 (40%) by a primary upper urinary tract tumor. On multivariable analyses, surgery was associated with a protective effect on CSM (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.59, confidence interval [CI]: 0.35–0.98, p = 0.04) and OM (HR: 0.45, CI: 0.37–0.99, p = 0.04) compared with patients treated with chemotherapy only. Similar results were found considering patients only surgically treated before the start of chemotherapy. After stratifying according to the number of metastatic sites, surgery has an effect on survival in patients with only one metastatic site, while no survival benefit was observed in patients with two or more metastatic sites. The study is limited by its retrospective nature.

Conclusions:

We found that surgery of the primary tumor site is associated with improved survival in patients with metastatic UC who received standard chemotherapy. This effect disappears in patients affected by two or more metastatic sites. Our results need to be validated in a high-quality prospective trial.

Patient summary:

In our multicenter, retrospective series, surgery in metastatic urothelial cancer patients improve survival compared with patients treated with chemotherapy only. This effect was evident in patients with limited disease extent, identified as one metastatic site.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Radical cystectomy, Metastatic, Local treatment, Urothelial carcinoma

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BCa) is the second most common genito-urinary malignancy, with 430 000 new cases diagnosed worldwide in 2012 [1]. Approximately, 10% of patients have at diagnosis unresectable or metastatic disease [2,3]. The current standard treatment for primary or secondary metastatic urothelial cancer (UC) is systemic platinum-based combination chemotherapy, resulting in poor long-term survival of approximately 15% within 5 yr [4]. Surgical removal of the primary tumor is an important part of the multimodal treatment of many metastatic urological and nonurological cancers. Several retrospective and population-based investigations reported feasibility and oncological effect of local treatment [5–8] in other urological cancers. Only few reports investigated the effect of local treatment on survival outcomes in metastatic UC [9–13]. Abufaraj et al. [12], in a recent systematic review, found that surgical resection of metastases is technically feasible and safely performed, and might improve cancer control and survival in very selected patients with limited metastatic burden. Consolidative extirpative surgery may also be considered in patients with clinically evident retroperitoneal node metastases if they have a response to chemotherapy. Similarly, results were found for patients with limited pulmonary metastases. Given the current paucity of evidence on this topic, new data are urgently required to validate these findings. We hereby present the first multicenter study testing the effect of surgery in the primary tumor site in metastatic UC patients by relying upon the Retrospective International Study of Invasive/Advanced Cancer of the Urothelium (RISC), one of the biggest available multicenter collaborations on advanced and metastatic UC.

2. Patients and methods

RISC is a retrospective database including individual patient-level data from patients with muscle-invasive or advanced UC or non-UC histology who have received systemic therapy in any clinical setting. This contemporary database includes data gathered from January 1, 2006 to January 1, 2011 from hospitals in the USA, Europe, Israel, and Canada. At the end of November 2018, data were extracted to select patients who fulfilled the following characteristics: (1) any primary tumor site (bladder or upper tract urothelial carcinoma [UTUC]), (2) de novo metastatic UC (cT1–4, cN0–3, and cM1), (3) complete data regarding local therapy (radical cystectomy [RC] or radical nephroureterectomy), and (4) administration of cisplatin- or carboplatin-containing chemotherapy in the first-line metastatic setting. Date of chemotherapy was not available for all patients; however, separate analyses (Table 1) including only patients who received surgery before starting chemotherapy were performed. The present study was approved by the ethics committees at each participating institution.

Table 1 –

Multivariable Cox regression analyses predicting cancer-specific and overall mortality in metastatic bladder cancer patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2011 with available date of surgery

| Variables | Multivariable CSM, 161 events | Multivariable OM, 177 events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.5 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.4 |

| Gender (Ref: female) | 1.04 (0.68–1.59) | 0.8 | 0.98 (0.66–1.47) | 0.9 |

| CCI | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 1.52 (0.83–2.78) | 0.2 | 1.37 (0.76–2.49) | 0.3 |

| ≥2 | 0.85 (0.57–1.25) | 0.4 | 0.87 (0.61–1.26) | 0.5 |

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Former smoker | 0.92 (0.52–1.61) | 0.7 | 0.80 (0.50–1.27) | 0.4 |

| Current smoker | 0.73 (0.41–1.28) | 0.2 | 0.88 (0.51–1.51) | 0.6 |

| Histology | ||||

| Transitional | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Variants | 1.20 (0.59–2.45) | 0.6 | 1.06 (0.52–2.16) | 0.8 |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| 1–2 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 3–4 | 0.94 (0.63–1.41) | 0.7 | 0.88 (0.60–1.29) | 0.5 |

| Clinical node | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| + | 1.03 (0.65–1.62) | 0.8 | 1.05 (0.68–1.62) | 0.8 |

| Chemotherapy type | ||||

| Cisplatin based | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Carboplatin based | 1.48 (0.93–2.35) | 0.1 | 1.45 (0.94–2.25) | 0.1 |

| Nonplatinum | 1.33 (0.52–3.41) | 0.5 | 1.19 (0.49–2.87) | 0.7 |

| Others | 1.35 (0.85–2.15) | 0.2 | 1.40 (0.90–2.17) | 0.1 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.03 | 0.91 (0.85–0.95) | 0.02 |

| Surgery in primary tumor site before chemotherapy | 0.44 (0.20–0.97) | 0.04 | 0.47 (0.22–0.98) | 0.04 |

CCI = Charlson comorbidity index; CI = confidence interval; CSM = cancer-specific mortality; HR = hazard ratio; OM = overall mortality; Ref = reference.

The study objective was to test the impact of surgery on survival outcomes in metastatic UC. Separate analyses were performed in the overall population and according to the number of metastatic sites. For the purpose of this study, metastatic sites were considered here as follows: for visceral metastases, the number of organs involved was considered, whereas for lymph node metastases, we counted any regional lymph node involvement as one anatomic site (typically, retroperitoneal metastases). The following parameters were used as covariates to adjust for possible confounders: age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), smoking habits (never smoker, former smoker, and current smoker), primary tumor location (bladder or UTUC), histology (transitional or variant histology), clinical T stage, clinical lymph node stage, chemotherapy regimen, number of chemotherapy cycles, and number of metastatic sites (ie, 1 vs >1). Primary survival endpoints were cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and overall mortality (OM).

2.1. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics of categorical variables focused on frequencies and proportions. Means, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported for continuously coded variables. The Mann-Whitney test and the chi-square test were used to compare the statistical significance of differences in medians and proportions, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the effect of surgery on CSM and OM rates. Cox regression analyses (for time-to-event outcomes) were performed to evaluate potential prognostic factors. Complete case analysis was performed, and no imputation was performed for missing data. Multivariable models were based on prespecified factors that were hypothesized to be clinically important. Analyses were performed in the overall population, and separately considering primary tumor location and the number of metastatic sites involved. Six-month landmark analysis was applied throughout, accounting for OM events. Analyses were repeated considering patients with primary BCa and those surgically treated before the start of chemotherapy. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Of the 326 individuals included in the study, 47 (14%) were treated with surgery in the primary tumor site. Clinical and pathological characteristics of our cohort stratified by surgical treatment of the primary tumor site are reported in Table 2. Patients treated with surgery share similar age, gender, smoking habits, CCI, presence of histological variants, clinical T stage, clinical N stage, metastatic location, and number of cycles of chemotherapy (all p ≥ 0.1). On the contrary, patients treated with surgery were more likely to have a primary tumor location in the UTUC compared with those who were treated with chemotherapy only (p = 0.002), were treated with different chemotherapy schemes, and had different metastatic site distributions. The reason why local treatment was indicated cannot be captured from the available information in the RISC database.

Table 2 –

Descriptive statistics of 326 patients treated with surgery in the primary tumor site in metastatic urothelial cancer between January 2006 and 2011

| Variables | Overall (n = 326,100%) | Surgery in the primary site (n = 47,14%) | No surgery (n = 279, 86%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||||

| Mean | 67 | 62 | 67 | 0.5 |

| Median (IQR) | 68 (59–75) | 62 (56–69) | 69 (60–75) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 246 (76%) | 37 (79%) | 209 (75%) | 0.5 |

| Female | 80 (24%) | 10 (21%) | 70 (25%) | |

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Current smoker | 69 (21%) | 12 (26%) | 57 (20%) | |

| Former smoker | 120 (37%) | 16 (34%) | 104 (37%) | 0.1 |

| Never smoker | 72 (22%) | 15 (32%) | 57 (20%) | |

| CCI | ||||

| 0 | 154 (47%) | 25 (54%) | 129 (46%) | 0.4 |

| 1 | 35 (11%) | 3 (6%) | 32 (11%) | |

| ≥2 | 126 (39%) | 16 (34%) | 110 (39%) | |

| Primary tumor | ||||

| Bladder | 252 (77%) | 28 (60%) | 224 (80%) | |

| Renal pelvis | 56 (17%) | 16 (34%) | 40 (14%) | 0.002 |

| Ureter | 18 (6%) | 3 (6%) | 15 (5%) | |

| Histological | ||||

| Transitional | 302 (93%) | 42 (90%) | 260 (93%) | 0.3 |

| Variants | 19 (6%) | 3 (6%) | 16 (6%) | |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| 1–2 | 122 (37%) | 22 (47%) | 100 (36%) | 0.3 |

| 3–4 | 127 (39%) | 17 (36%) | 110 (39%) | |

| Clinical N stage | ||||

| 0 | 70 (21%) | 8 (17%) | 62 (22%) | 0.4 |

| + | 139 (43%) | 19 (40%) | 120 (43%) | |

| Chemotherapy type | ||||

| Cisplatin based | 136 (42%) | 14 (30%) | 122 (44%) | |

| Carboplatin based | 78 (24%) | 9 (19%) | 69 (25%) | 0.02 |

| Nonplatinum | 14 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 13 (5%) | |

| Others | 98 (30%) | 23 (49%) | 75 (27%) | |

| Number of cycles of chemotherapy | ||||

| Mean | 5 | 6 | 5 | 0.08 |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (3–6) | 5 (3–7) | 6 (4–6) | |

| Metastatic sites | ||||

| 1 | 140 (43%) | 14 (30%) | 126 (45%) | |

| 2 or more | 174 (54%) | 28 (60%) | 146 (52%) | 0.007 |

| Metastatic locationa | ||||

| Extrapelvic nodes | 71 (22%) | 8 (17%) | 63 (23%) | |

| Lung | 28 (9%) | 4 (9%) | 24 (9%) | 0.4 |

| Bone | 24 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 23 (8%) | |

| Liver | 13 (4%) | 13 (5%) | ||

| Others | 4 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (1%) | |

CCI = Charlson comorbidity index; IQR = interquartile range.

Refers to patients with the involvement of one metastatic site.

3.2. Survival estimates

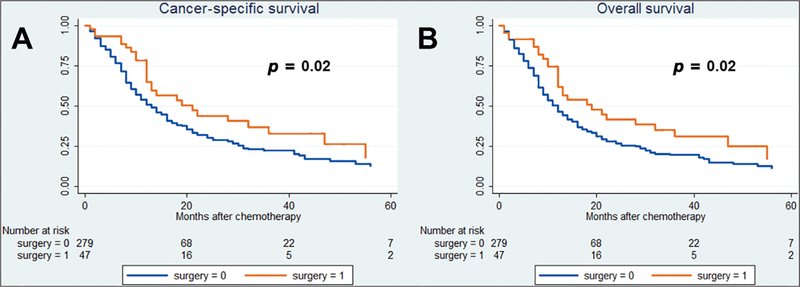

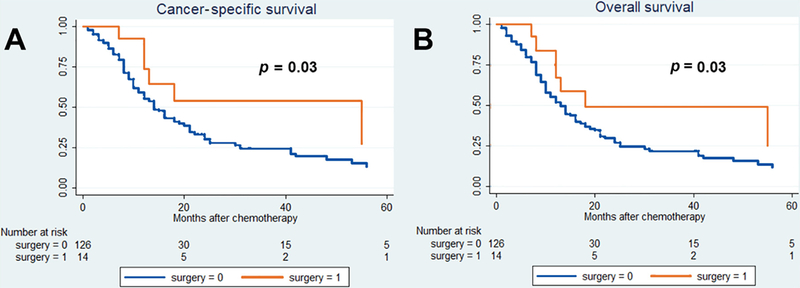

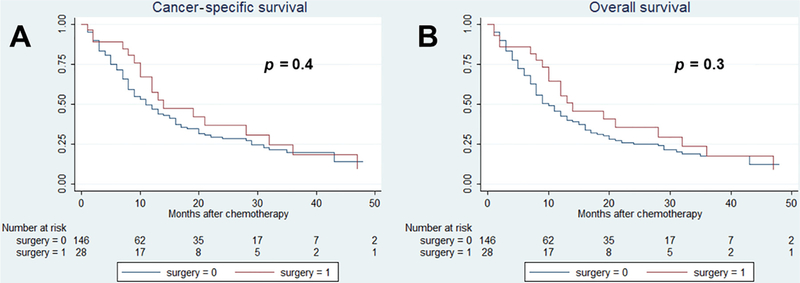

After a median (IQR) follow-up of 43 (33–45) mo, 212 cancer-specific and 232 overall causes of deaths were reported. The 36-mo cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) in patients treated versus those not treated with surgery were, respectively, 22% versus 37% (p = 0.02) and 20% versus 35% (p = 0.02; Fig. 1). Fig. 2 shows the analysis of patients with only one metastatic site. The 36-mo CSS and OS in patients treated versus those not treated with surgery were 25% versus 52% (p = 0.03) and 23% versus 50% (p = 0.03), respectively. In Fig. 3, patients with two or more metastatic sites are considered. The 36-mo CSS and OS in patients treated versus those not treated with surgery were, respectively, 22% versus 23% (p = 0.4) and 22% versus 23% (p = 0.3). We evaluated the impact of surgery on survival in metastatic UC in multivariable Cox regression analyses (Table 3). Surgery was associated with a protective effect on CSM (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.59, confidence interval [CI]: 0.35–0.98, p = 0.04) and OM (HR: 0.45, CI: 0.37–0.99, p = 0.04) compared with patients treated with chemotherapy only. In Table 4, evaluation of patients with BCa only is reported. Similarly, surgery was associated with a protective effect on CSM (HR: 0.44, CI: 0.22–0.89, p = 0.02) and OM (HR: 0.48, CI: 0.25–0.92, p = 0.03) compared with patients treated with chemotherapy only. Finally, analyses were repeated considering only patients who received surgery before the start of chemotherapy (Table 1). Surgery was associated with a protective effect on CSM (HR: 0.44, CI: 0.20–0.97, p = 0.04) and OM (HR: 0.47, CI: 0.22–0.98, p = 0.04) compared with patients treated with chemotherapy only.

Fig. 1 –

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of (A) cancer-specific mortality and (B) overall mortality in cT1–4cN0–3cM1 patients with or without surgical local treatment.

Fig. 2 –

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of (A) cancer-specific mortality and (B) overall mortality in cT1–4cN0–3cM1 patients affected by one metastatic site with or without surgical local treatment.

Fig. 3 –

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of (A) cancer-specific mortality and (B) overall mortality in cT1–4cN0–3cM1 patients affected by two or more metastatic sites with or without surgical local treatment.

Table 3 –

Multivariable Cox regression analyses predicting cancer-specific and overall mortality in metastatic urothelial cancer patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2011

| Variables | Multivariable CSM, 212 events | Multivariable OM, 232 events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.4 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.3 |

| Gender (Ref: female) | 1.03 (0.72–1.50) | 0.8 | 0.98 (0.69–1.39) | 0.9 |

| CCI | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 1.13 (0.70–1.83) | 0.6 | 1.10 (0.69–1.77) | 0.6 |

| ≥2 | 0.78 (0.55–1.10) | 0.1 | 0.82 (0.59–1.13) | 0.2 |

| Primary tumor location | ||||

| Bladder vs UTUC | 1.04 (0.72–1.51) | 0.8 | 1.00 (0.70–1.43) | 0.9 |

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Former smoker | 0.84 (0.52–1.36) | 0.3 | 0.84 (0.56–1.26) | 0.4 |

| Current smoker | 0.73 (0.45–1.20) | 0.5 | 0.86 (0.54–1.37) | 0.5 |

| Histology | ||||

| Transitional | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Variant | 1.50 (0.79–2.87) | 0.2 | 1.36 (0.72–2.59) | 0.3 |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| 1–2 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 3–4 | 0.87 (0.61–1.23) | 0.4 | 0.82 (0.59–1.14) | 0.2 |

| Clinical node | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| + | 1.11 (0.75–1.64) | 0.6 | 1.08 (0.75–1.57) | 0.7 |

| Chemotherapy type | ||||

| Cisplatin based | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Carboplatin based | 1.36 (0.93–1.99) | 0.1 | 1.33 (0.92–1.91) | 0.1 |

| Nonplatinum | 1.53 (0.74–3.17) | 0.2 | 1.45 (0.74–2.86) | 0.3 |

| Others | 1.20 (0.79–1.81) | 0.4 | 1.22 (0.83–1.81) | 0.3 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | 0.91 (0.86–0.98) | 0.007 | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) | 0.003 |

| Surgery in primary tumor site | 0.59 (0.35–0.98) | 0.04 | 0.45 (0.37–0.99) | 0.04 |

CCI = Charlson comorbidity index; CI = confidence interval; CSM = cancer-specific mortality; HR = hazard ratio; OM = overall mortality; Ref = reference; UTUC = upper tract urothelial carcinoma.

Table 4 –

Multivariable Cox regression analyses predicting cancer-specific and overall mortality in metastatic bladder cancer patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2011

| Variables | Multivariable CSM, 163 events | Multivariable OM, 180 events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.4 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.3 |

| Gender (Ref: female) | 1.08 (0.71–1.64) | 0.7 | 1.01 (0.68–1.51) | 0.9 |

| CCI | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 1.47 (0.81–2.69) | 0.2 | 1.40 (0.79–2.49) | 0.2 |

| ≥2 | 0.78 (0.53–1.16) | 0.2 | 0.82 (0.57–1.18) | 0.3 |

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Former smoker | 0.76 (0.47–1.23) | 0.3 | 0.81 (0.51–1.29) | 0.4 |

| Current smoker | 0.95 (0.55–1.65) | 0.8 | 0.91 (0.54–1.55) | 0.7 |

| Histology | ||||

| Transitional | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Variants | 1.23 (0.60–2.51) | 0.5 | 1.09 (0.54–2.20) | 0.8 |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| 1–2 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 3–4 | 0.99 (0.66–1.48) | 0.9 | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 0.6 |

| Clinical node | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| + | 1.03 (0.65–1.62) | 0.9 | 1.03 (0.68–1.58) | 0.8 |

| Chemotherapy type | ||||

| Cisplatin based | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Carboplatin based | 1.48 (0.93–2.34) | 0.1 | 1.43 (0.93–2.22) | 0.1 |

| Nonplatinum | 1.33 (0.52–3.41) | 0.5 | 1.18 (0.49–2.82) | 0.7 |

| Others | 1.29 (0.82–2.06) | 0.3 | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 0.2 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.03 | 0.91 (0.84–0.98) | 0.01 |

| Surgery in primary tumor site | 0.44 (0.22–0.89) | 0.02 | 0.48 (0.25–0.92) | 0.03 |

CCI = Charlson comorbidity index; CI = confidence interval; CSM = cancer-specific mortality; HR = hazard ratio; OM = overall mortality; Ref = reference.

4. Discussion

The role of surgery in metastatic patients affected by urological malignancies is gaining importance [5–8]. However, limited information is available regarding the effect of surgery or bladder irradiation in the treatment of metastatic UC. Seisen et al. [13] raised the hypothesis that definitive local treatment (surgery or radiotherapy) provides a therapeutic benefit in metastatic UC patients, using the National Cancer Database. They identified 3753 patients who received multiagent systemic chemotherapy, of whom 297 (7.9%) received a concomitant local treatment. They reported an OS benefit for individuals with metastatic UC treated with local treatment compared with those treated with chemotherapy only. At the time, no report evaluated the effect of surgery in metastatic UC patients [9,12]. Similarly, Li et al. [10] reported in a single-center experience that cytoreductive RC is feasible and provides longer CSS in BCa patients with a solitary metastasis. Following these initial experiences, the aim of our investigation was to validate these findings using the RISC database, the biggest multicenter collaboration on advanced and metastatic UC.

Our results show that local treatment with standard chemotherapy provides a survival benefit in terms of CSS and OS compared with metastatic UC patients treated with chemotherapy only. Our primary analyses (Table 3) included patients with both primary BCa and UTUC. Although several data exist reporting demographics, and pathological and survival differences between these two entities [14], in a recent post hoc analysis, similar survival outcomes were reported irrespective of primary tumor location (bladder, renal pelvis, or ureter) for patients treated within the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trials (30924, 30986, and 30987) of metastatic UC [15]. However, in a previously reported analysis of the EORTC 30987 trial [16] and the recent analysis of the ramucirumab trial [17], differences between upper and lower tracks have been observed. On the contrary, in a sensitivity analysis including only patients affected by BCa, we found improved survival outcomes for patients treated with surgery compared with those treated with chemotherapy only (Table 4).

We included in the analyses only patients treated with optimal surgical treatment (radical nephroureterectomy or RC), and all the patients who underwent suboptimal surgery such as partial cystectomy were excluded. In this regard, partial cystectomy is insufficient for the treatment of locally advanced BCa and should not be recommended in the standard management of UC [18]. All patients who received radiotherapy to the primary tumor site were excluded from the final analyses. In this regard, our study tested for the first time the effect of surgery on the primary tumor, whereas previous studies tested the effect of local therapy, including radiotherapy, and surgery together [13]. The potential effect of cytoreductive surgery in the metastatic setting has not been evaluated in the context of improved local tumor control, but evaluated for other biological reasons such as the seed and soil theory. According to this theory, the primary tumor produces growth factors that might be able to activate an environment favorable to the dissemination of malignant clones and formation of metastases. In this regard, the necessity of a radical treatment might have several effects in patients with localized invasive BCa [19–21]. Analyses were finally repeated considering only patients who received surgery before the start of chemotherapy, reporting again a protective effect of surgery on survival compared with patients treated with chemotherapy only. Moreover, growing retrospective evidence suggests that a survival benefit might be provided by tumor metastasectomy in well-selected patients [22]. This aspect needs to be evaluated further.

Although this effect was proved in the whole population, when stratified according to the number of metastatic sites, we observed that patients affected by a low tumor burden were the only ones who benefited from local therapy in terms of CSS and OS (Figs. 1–3). In this context, although preliminary, these data might show a different biological outcome on the basis of metastatic burden as shown for other tumors [7]. Despite the majority of patients presenting with one metastatic site ultimately harbored retroperitoneal lymph node metastases (as in the study by Seisen et al. [13]), we could extend the assumption that similar survival benefit may be obtained with local treatment in the remainder presenting with visceral metastatic involvement. Indeed, the granular distribution of small numbers prevented us from applying statistical tests to validate this hypothesis.

In comparison with previous studies published on this topic, our report has several strengths. First, our analyses were based on patients treated with cisplatin- or carboplatin-containing chemotherapy as the standard first-line treatment in the metastatic setting. In this regard, our population represents the current standard of care. This accurateness in selecting the studied population cannot be achieved considering a population-based analyses. Second, our multivariable model was adjusted for the most important confounders regarding UC. For example, smoking history and presence of histological variants play an important role in determining survival outcomes in UC patients, and should be taken into consideration in survival models. Third, we included both patients affected by BCa and those affected by UTUC. The current trials in the metastatic setting are based on the results of patients with both the primary tumor locations, and these two subgroups of patients should be considered together. Fourth, we were able to observe that the beneficial effect of local treatment might be reserved for patients affected by a low metastatic tumor burden.

Our study is not devoid of limitations. First, our study was not prospective or randomized, as it was a retrospective chart review, and our findings should be interpreted in this context. However, such retrospective studies are usually a precursor of more extensive prospective investigations. Similarly for BCa, the effect of surgery in oligometastatic prostate cancer patients [5,23] has been tested in small retrospective series before organizing large prospective trials. Second, all patients included in our cohort underwent local treatment at a high-volume tertiary referral center. Therefore, findings might represent this specific clinical scenario and not be applicable to other settings. The use of surgery is dependent on many factors, and differences might be present [24] with the selection of different patients. Third, all metastatic UC patients where considered together. RC is a potentially morbid surgery [25], and data helping physicians in selecting patients who might benefit more from local treatment are urgently needed [26]. Fourth, no data regarding the extension of lymphadenectomy and its potential impact on survival were available for this series. Lastly, information behind the decision for local therapy is not available in the RISC database.

5. Conclusions

In our multicenter collaboration, 14% of metastatic UC patients were treated with surgery in the primary tumor site as a part of multimodal treatment. We found that surgery improves CSS and OS even after adjusting for all the available confounders. These results were confirmed in patients with single-site metastatic disease, but the effect disappeared in the analysis of patients with two or more metastatic sites. Our results need to be validated in a prospective trial of patients who meet the selection criteria.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: Marco Moschini certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

References

- [1].Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor A, Jemal A, Bray F. Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: a global overview and recent trends. Eur Urol 2017;71:96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kamat AM, Hegarty PK, Gee JR, et al. ICUD-EAU international consultation on bladder cancer 2012: screening, diagnosis, and molecular markers. Eur Urol 2013;63:4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zaffuto E, Bandini M, Moschini M, et al. Location of metastatic bladder cancer as a determinant of in-hospital mortality after radical cystectomy. Eur Urol Oncol 2018;1:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sooriakumaran P, Karnes J, Stief C, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of perioperative outcomes in 106 men who underwent radical prostatectomy for distant metastatic prostate cancer at presentation. Eur Urol 2016;69:788–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moschini M, Soria F, Briganti A, Shariat SFF. The impact of local treatment of the primary tumor site in node positive and metastatic prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2016;20:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumourfornewlydiagnosed, metastaticprostatecancer(STAMPEDE):a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;392:2353–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Méjean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, et al. Sunitinib alone or after nephrectomy in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;379:417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abufaraj M, Gust K, Moschini M, et al. Management of muscle invasive, locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a literature review with emphasis on the role of surgery. Transl Androl Urol 2016;5:735–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li R, Kukreja JEB, Seif MA et al. The role of metastatic burden in cytoreductive/consolidative radical cystectomy. World J Urol. 2019. March 12 10.1007/s00345-019-02693-y. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li R, Metcalfe M, Kukreja J, Navai N. Role of radical cystectomy in non-organ confined bladder cancer: a systematic review. Bladder Cancer 2018;4:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Abufaraj M, Dalbagni G, Daneshmand S, et al. The role of surgery in metastatic bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2018;73:543–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Seisen T, Sun M, Leow JJ, et al. Efficacy of high-intensity local treatment for metastatic urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a propensity score–weighted analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Green DA, Rink M, Xylinas E, et al. Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and the upper tract: disparate twins. J Urol 2013;189:1214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Moschini M, Shariat SF, Rouprêt M, et al. Impact of primary tumor location on survival from the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer advanced urothelial cancer studies. J Urol 2018;199:1149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bellmunt J, Petrylak DP. New therapeutic challenges in advanced bladder cancer. Semin Oncol 2012;39:598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gross-Goupil M, Kwon TG, Eto M, et al. 863OAxitinib vs placebo in patients at high risk of recurrent renal cell carcinoma (RCC): ATLAS trial results. Ann Oncol 2018;29:mdy283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Alfred Witjes J, Lebret T, Compérat EM, et al. Updated 2016 EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. Eur Urol 2017;71:462–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Psaila B, Lyden D. The metastatic niche: adapting the foreign soil. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited—the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. Int J Cancer 2011;128:2527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2003;3:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Faltas BM, Gennarelli RL, Elkin E, Nguyen DP, Hu J, Tagawa ST. Metastasectomy in older adults with urothelial carcinoma: Population-based analysisof useandoutcomes. UrolOncol 2018;36:9.e11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Moschini M, Morlacco A, Kwon E, Rangel LJ, Karnes RJ. Treatment of M1a/M1b prostate cancer with or without radical prostatectomy at diagnosis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2017;20:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Williams SB, Hudgins HK, Ray-Zack MD, et al. Systematic review of factors associated with the utilization of radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 2019;2:119–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Moschini M, Simone G, Stenzl A, Gill ISIS, Catto J. Critical review of outcomes from radical cystectomy: can complications from radical cystectomy be reduced by surgical volume and robotic surgery? Eur Urol Focus 2016;2:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Psutka SP, Barocas DA, Catto JWF, et al. Staging the host: personalizing risk assessment for radical cystectomy patients. Eur Urol Oncol 2018;1:292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]