Abstract

Objective:

Ventricular tachyarrhythmia is the leading cause of death in post-infarction patients. Big endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a potent vasoconstrictor peptide and plays a role in ventricular tachyarrhythmia development. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between the serum concentration of big ET-1 and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in post-infarction left ventricular aneurysm (PI-LVA) patients.

Methods:

A total of 222 consecutive PI-LVA patients who had received medical therapy were enrolled in the study. There were 43 (19%) patients who had ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) at the time of admission. The clinical characteristics were observed and the plasma big ET-1 level was measured. Associations between big ET-1 and the presence of VT/VF were assessed. Patients were followed up to check for outcomes related to cardiovascular mortality, VT/VF attack, and all-cause mortality.

Results:

The median concentration of big ET-1 was 0.635 pg/mL. Patients with big ET-1 concentrations above the median were more likely to have higher risk clinical features. There was a positive correlation between the level of big ET-1 with VT/VF attack (r=0.354, p<0.001). In the multiple logistic regression analysis, big ET-1 (OR=4.06, 95%CI:1.77-9.28, p<0.001) appeared as an independent predictive factor for the presence of VT/VF. Multiple Cox regression analysis suggested that big ET-1 concentration was independently predictive of VT/VF attack (OR=2.5, 95% CI 1.4–4.5, p<0.001). NT-proBNP and left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤35% were demonstrated to be independently predictive of cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality.

Conclusion:

Increased big ET-1 concentration in PI-LVA patients is a valuable independent predictor for the prevalence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and VT/VF attacks during follow-up after PI-LVA treatment.

Keywords: big endothelin-1, ventricular tachyarrhythmia, post-infarction left ventricular aneurysm

Introduction

Ventricular tachyarrhythmia is a negative prognostic factor in patients with myocardial infarction and post-infarction left ventricular aneurysm (PI-LVA) formation (1). Adverse ventricular remodeling in PI-LVA patients results in progressive ventricular dilation and subsequent contractile dysfunction, both of which are arrhythmogenic substrates. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is an endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor peptide that is produced under conditions of inflammation, neurohormonal activation, hypoxia, and vascular stress (2). ET-1 is an endogenous arrhythmogenic substance (3-5) and may elicit severe ventricular arrhythmias. However, there is limited evidence regarding the relationship between plasma ET-1 levels and the presence of ventricular tachyarrhythmia in PI-LVA patients.

Due to of its rapid clearance, ET-1 has a short biological half-life in circulation. Big ET-1 is a 39-amino-acid precursor of ET-1. The half-life of big ET-1 in vivo is much longer than that of ET-1, and big ET-1 has been proven to be a relatively better target for the investigation of the secretory activity of the endothelial system (6). We hypothesized that the serum concentration of big ET-1 would have an impact on ventricular tachyarrhythmia in PI-LVA patients. This study aimed to determine the association between big ET-1 levels in the plasma and ventricular tachyarrhythmia, and to investigate its prognostic value in PI-LVA patients.

Methods

Study population

A total of 513 patients diagnosed with PI-LVA by coronary angiography between January 2012 and September 2016 in our single center were initially considered for enrollment in this study. Among these patients, 222 PI-LVA patients who underwent medical therapy were recruited. The presence of PI-LVA was confirmed by a history of previous myocardial infarction and an aneurysm depicted by ultrasonography examination or coronary angiography. Patients with a history of cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, congenital heart disease, and occurrence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) within the past 8 weeks were excluded. Patients with ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) occurring within 48 hours of the AMI symptom onset were also not included in this study. VT/VF was defined as tachycardia of ventricular origin lasting for more than 30 seconds or complete hemodynamic instability, which was either self-terminated or required pharmacological/electrical cardioversion due to hemodynamic collapse. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Central Committee of our hospital and the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, and the investigations complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients prior to the start of the study.

Data acquisition

The data of the enrolled patients were reviewed to determine arrhythmia findings, past medical history, and clinical management. Data on the clinical management of arrhythmia, including pharmacological treatment, catheter ablation, and implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronized therapy cardioverter defibrillation, were also collected. Two independent reviewers evaluated all the arrhythmia-related data. The left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVEDD) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were determined by echocardiography during the period of hospitalization. Big ET-1, NT-proBNP, and creatinine were measured by standard biochemical tests. Patients were classified into two groups according to the median concentration of plasma big ET-1 level. We compared the risk factors for VT/VF between the two groups.

Follow-up

Patients were followed up for outcomes including VT/VF attack, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. Processes for identification and adjudication of clinical endpoints were performed, including a review of medical records and follow-up phone calls with the patients. Mortality was classified into cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular, and in cases when the cause of death was unknown or unwitnessed, a cardiac cause was assumed. A VT/VF attack was defined as recorded tachycardia of ventricular origin, with appropriate ICD shocks or external cardioversion during the follow-up period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and compared using the two-sample Student’s t-test and analysis of variance. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies with percentages and compared by the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Patients were grouped according to their plasma big ET-1 concentration, which was dichotomized at the median. We compared the risk factors for VT/VF between the two big ET-1 groups. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify variables with a significant independent association with VT/VF. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed using median big ET-1. Age- and sex-adjusted Cox proportional hazard regression was used to predict each VT/VF attack, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality.

Results

Population characteristics

This study ultimately consisted of 222 PI-LVA patients. The mean age was 58±10 years, and 191 (86%) patients were male. The median concentration of big ET-1 was 0.635 pg/mL. Baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics between those with big ET-1 concentrations below and above the median were compared (Table 1). No significant differences were observed between the two groups with reference to age and sex. Patients with big ET-1 concentrations above the median were associated with an increased proportion of VT/VF presence (30% vs. 8%, p<0.001) and higher concentrations of NT-proBNP (1887 pg/mL vs. 1197 pg/mL, p<0.001). Echocardiographic characteristics of the study populations showed enlarged LVEDD and decreased LVEF in patients with big ET-1 concentrations above the median. The proportions of patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, spironolactone, beta-blocking agents, and statins were comparable between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with big ET-1 levels at above and below the median concentration

| All patients n=222 | Big ET-1≤ median n=111 | Big ET-1> median n=111 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58±10 | 57±9 | 58±11 | 0.165 |

| Males (n) | 191 (86) | 97 (87) | 94 (85) | 0.699 |

| Hypertension (n) | 99 (89) | 50 (45) | 49 (44) | 0.5 |

| DM (n) | 60 (27) | 20 (18) | 40 (36) | 0.004 |

| NYHA class III-IV (n) | 71 (32) | 27 (24) | 44 (40) | 0.021 |

| LVEDD (n) | 60±8 | 59±7 | 60±8 | 0.720 |

| LVEDD>60 (n) | 99 (45) | 43 (39) | 56 (50) | 0.052 |

| LVEF (%) | 38±8 | 40±8 | 37±9 | 0.077 |

| LVEF<35% (n) | 61 (27) | 23 (21) | 38 (34) | 0.035 |

| VT/VF (n) | 43 (19) | 9 (8) | 34 (30) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1539±1268 | 1197±919 | 1887±1469 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 97±20 | 90±23 | 103±16 | 0.127 |

| AF/AFL (n) | 20 (9) | 11 (10) | 9 (8) | 0.815 |

| Multivessel disease (n) | 99 (45) | 52 (47) | 47 (42) | 0.589 |

| Moderate/severe MR (n) | 90 (41) | 40 (36) | 50 (45) | 0.218 |

| ACEI/ARB (n) | 190 (86) | 98 (88) | 92 (83) | 0.788 |

| Statins (n) | 172 (77) | 82 (74) | 90 (81) | 0.361 |

| Beta-blockers (n) | 195 (88) | 102 (92) | 93 (84) | 0.392 |

| Spironolactone (n) | 198 (89) | 98 (88) | 100 (90) | 0.833 |

DM - diabetes mellitus, NYHA - New York Heart Association classification, LVEDD - left ventricular end diastolic dimension, LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction,

VT/VF - ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation, AF/AFL - atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, MR - mitral regurgitation, ACEI/ARB - angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers

Big ET-1 and the presence of VT/VF

A positive correlation was found between big ET-1 and VT/VF (r=0.354, p<0.001), NT-proBNP (r=0.509, p<0.001), New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III-IV (r=0.215, p=0.001), mitral regurgitation (r=0.159, p=0.018), DM (r=0.200, p=0.003), and AF (r=0.176, p=0.008) (Table 2). A negative correlation was found between big ET-1 and LVEF (r=-0.181, p=0.007, Table 2). In the univariate logistic regression analysis, NT-proBNP, NYHA class III-IV, mitral regurgitation, multivessel disease, LVEF, and big ET-1 were significantly correlated with the presence of VT/VF. Data from multiple analysis (Table 3) suggested that apart from several factors, big ET-1 above the median remained an independent predictor of VT/VF (OR=4.06, 95% CI: 1.77-9.28, p=0.001).

Table 2.

Correlation between a big ET-1 level and other variables

| All patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | P value | |

| VT/VF | 0.354 | <0.001 |

| LVEDD | 0.066 | 0.328 |

| LVEF | -0.181 | 0.007 |

| NT-proBNP | 0.509 | <0.001 |

| NYHA class III-IV | 0.215 | 0.001 |

| Moderate/severe MR | 0.159 | 0.018 |

| Multivessel disease | 0.029 | 0.670 |

| Male sex | 0.055 | 0.414 |

| Age | 0.035 | 0.603 |

| DM | 0.200 | 0.003 |

| AF | 0.176 | 0.008 |

VT/VF - ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation, LVEDD - left ventricular end diastolic dimension, LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA - New York Heart Association classification, MR - mitral regurgitation, DM - diabetes mellitus,

AF - atrial fibrillation

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis for variables predicting VT/VF development

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multiple analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Big ET-1 | 5.24 (2.46-11.1) | <0.001 | 4.06 (1.77-9.28) | 0.001 |

| Big ET-1>median | 5.00 (2.27-11.0) | <0.001 | ||

| NT-proBNP | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | <0.001 | ||

| NYHA class III-IV | 5.18 (2.56-10.5) | <0.001 | 4.32 (1.83-10.2) | 0.001 |

| LVEF | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | 0.003 | ||

| LVEF≤35% | 2.58 (1.29-5.17) | 0.007 | ||

| LVEDD | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) | 0.001 | ||

| LVEDD>60 | 3.68 (1.80-7.54) | <0.001 | 3.14 (1.32-7.49) | 0.022 |

| Multivessel disease | 0.47 (0.23-0.96) | 0.037 | ||

| Moderate/severe MR | 2.16 (1.10-4.24) | 0.025 | ||

NYHA - New York Heart Association classification, LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction, LVEDD - left ventricular end diastolic dimension, MR - mitral regurgitation

Big ET-1 and incident VT/VF attack, cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality

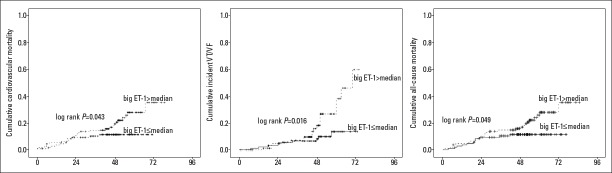

Follow-up was completed for all patients. The median follow-up period for the entire study group was 40±15 months (range: 1–67 months). During the follow-up, 29 patients (29/222, 13%) had VT/VF attacks, 38 (38/222, 17%) patients died, and 36 patients (36/222, 16%) died from cardiovascular reasons. In cumulative hazard K-M analyses, big ET-1 concentrations above the median were associated with an increased risk of incident VT/VF attack (log-rank p=0.016), cardiovascular mortality (log-rank p=0.043), and all-cause mortality (log-rank p=0.049) (Fig. 1). In Cox regression models adjusted for clinical variables and other prognostic biomarkers, big ET-1 concentration was predictive of VT/VF attack (OR=2.5, 95% CI 1.4–4.5, p<0.001). LVEF≤35% was another independent predictive factor of VT/VF attack (Table 4). In contrast, big ET-1 showed no clear association with cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. Univariate analysis revealed that big ET-1 (p=0.008), NT-proBNP (p=0.008), LVEDD ≥60 mm (p=0.022), LVEF ≤35% (p=0.008), NYHA class III-IV (p=0.050), and moderate/severe MR (p=0.005) were independent predictors of cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality (Table 4). On multiple analysis, NT-proBNP and LVEF ≤35% were demonstrated to be independently correlated with a favorable clinical outcome.

Figure 1.

K-M analyses for incident VT/VF attack, cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality.

K-M analyses dichotomized by median big ET-1 concentration showed that higher big ET-1 concentrations were associated with a higher risk of incident VT/VF attack (log-rank P=0.016), cardiovascular mortality (log-rank P=0.043) and all-cause mortality (log-rank P=0.049)

Table 4.

Cox regression analysis of VT/VF attack, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality in 222 PI-LVA patients

| VT/VF attack | Cardiovascular mortality | All-cause mortality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multiple HR (95% CI) | P value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multiple HR (95% CI) | P value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multiple HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Big ET-1 | 2.8 (1.7-4.9) | <0.01 | 2.5 (1.4-4.5) | 0.00 | 2.3 (1.4-3.5) | <0.01 | 2.2 (1.4-3.4) | <0.01 | ||||

| Big ET-1>median | 2.6 (1.2-5.7) | 0.02 | 2.1 (1.0-4.2) | 0.05 | 2.0 (1.0-3.9) | 0.05 | ||||||

| NT-proBNP | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 0.02 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | <0.01 | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 0.00 | 1.0 (1.0-1.2) | <0.01 | 1.0 (1.0-1.2) | <0.01 | ||

| LVEDD | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 0.02 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | <0.01 | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | <0.01 | ||||||

| LVEDD>60 | 3.0 (1.3-6.6) | 0.01 | 2.6 (1.3-5.1) | 0.01 | 2.5 (1.5-4.8) | 0.01 | ||||||

| LVEF | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | 0.04 | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | 0.01 | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | <0.01 | ||||||

| LVEF≤35% | 3.2 (1.6-5.9) | <0.01 | 2.4 (1.1-5.4) | 0.02 | 2.5 (1.3-4.9) | 0.01 | 2.2 (1.1-4.4) | 0.02 | 2.3 (1.2-4.4) | 0.01 | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | 0.03 |

| NYHA class III-IV | 2.2 (1.0-4.7) | 0.04 | 2.6 (1.4-5.1) | 0.01 | 2.6 (1.4-4.9) | <0.01 | ||||||

| Mitral regurgitation | 2.0 (0.9-4.2) | 0.06 | 2.7 (1.4-5.4) | 0.01 | 2.6 (1.4-5.1) | 0.01 | ||||||

VT/VF - ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation, LVEDD - left ventricular end diastolic dimension, LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA - New York Heart Association classification

Discussion

Plasma concentrations of big ET-1 were increased in PI-LVA patients. The present study demonstrated the correlation between big ET-1 and VT/VF prevalence in PI-LVA patients who underwent medical therapy. We showed that big ET-1 levels above the median were positively associated with the presence of VT/VF at the time of hospital admission, and plasma big ET-1 levels were an independent risk factor for VT/VF attack during the follow-up period.

Big ET-1 and ventricular tachycardia

Big ET-1 is a precursor protein and is thought to be more stable in circulation than ET-1. Big ET-1 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases through several processes, including vasoconstriction, proinflammatory actions, proliferative effects, and free radical formation (7). The relation between big ET-1 and arrhythmogenesis has attracted considerable research interest. This study demonstrated a positive association between big ET-1 and VT/VF at admission, and plasma big ET-1 levels independently predicted VT/VF attack during follow-up. Several possible mechanisms account for these findings.

First, cardiac sympathetic nerves are injured after myocardial infarction. Previous basic and clinical studies have suggested the importance of sympathetic activation in the development of lethal ventricular arrhythmias, and inhomogeneity in myocardial sympathetic innervation is vulnerable to arrhythmic death (8). The PAREPET study showed that sympathetic denervation predicts SCD independently of LVEF and infarct volume (9). A clinical study (10) reported an increase in plasma ET-1 levels in patients with sympathetic activation. Experimental data (11) demonstrated that ET-1 plays a prominent pathophysiological role in the process of norepinephrine release from sympathetic nerve endings. Through an ET-1-mediated pathway, failing cardiomyocytes can induce nerve growth factor (NGF), which is critical for sympathetic nerve sprouting (12). The upregulation of NGF and enhanced myocardial nerve sprouting were suggested to cause a dramatic increase in SCD, which resulted in a high incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias (13, 14).

Second, the regulatory action of ET-1 on ion currents has been demonstrated by cellular studies. ET-1 inhibited the L-type calcium current and the delayed the rectifier potassium channel (15). The action of ET-1 on the transient outward current (Ito) may promote the occurrence of early afterdepolarizations under certain conditions (16). Third, an additional mechanism of ET-1-mediated arrhythmogenesis may occur through the effects of ET-1 on gap junctions. An in vitro study (17) examined the impulse conduction of neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes and showed a reduction in conduction velocity and gap junctional remodeling after exposure to ET-1. As stated above, the interaction between big ET-1 and sympathetic activation/innervation and the complex electrophysiological actions of big ET-1 on ion channels and gap junctions suggested an important pathophysiological role of big ET-1 in the genesis of VT/VF.

Big ET-1 and clinical outcome

In accordance with previous studies, the results of our study indicated that NT-proBNP (18, 19) and LVEF≤35% (20) were independent predictive factors of clinical outcome in patients post-myocardial infarction. However, big ET-1 is not one of the independent predictors of cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality in PI-LVA patients, although this study showed that increased big ET-1 was associated with worse LVEF, enlarged LVEDD, and elevated plasma NT-proBNP levels.

Big ET-1 levels were reported to be increased in heart failure (21) and ischemia (22) patients. ET-1 increases myocardial necrosis and arrhythmogenesis in myocardial infarction. In the chronic post-infarction phase, ET-1 increases the left ventricular afterload and participates in the myocardial fibrotic process. As a consequence, ET-1 is predictive of a poor clinical prognosis (23, 24). A meta-analysis (25) also showed that increased plasma levels of big ET-1 in heart failure populations were associated with poor prognosis or mortality. However, in comparison to natriuretic peptides, the prognostic importance of ET-1 has been mixed. NT-proBNP was recommended by current guidelines as the biomarker with the strongest prognostic value for heart failure (26). Masson et al. (24) reported that in a large population of patients with symptomatic heart failure, the circulating concentration of big ET-1 was an independent marker of mortality and morbidity, but BNP remained the strongest neurohormonal prognostic factor. Unlike existing studies, the results from this study did not suggest a prognostic significance of big ET-1 in PI-LVA patients. Delta changes in big ET-1 concentrations over time may further improve prognostic significance.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be taken into consideration in this study. The major limitation was the observational retrospective study design, which may have let to selection bias, however, multiple Cox regression analysis was used to minimize residual confounding. Our results were obtained from a moderate sample size and further studies with larger cohorts of patients might provide more precise insights into the predictive value of big ET-1 on the presence of VT/VF and its prognostic implications. In addition, it is unknown whether these results are applicable for longer follow-up durations, considering that adverse clinical outcomes in PI-LVA patients tended to aggregate over time.

Conclusion

Increased big ET-1 concentrations in PI-LVA patients were shown to be significantly associated with the presence of ventricular tachyarrhythmia. We concluded that big ET-1 is a valuable independent predictor of VT/VF attacks. The results of this study may be of clinical interest since the assessment of big ET-1 could improve risk stratification and provide new insights into biomarker-guided targeted therapies for VT/VF.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – X.N.; Design – X.N.; Supervision – S.Z., Xiaoli Zhang; Funding – None; Materials – Z.Y., F.W.; Data collection and/or processing – Y.S., X.Y., Z.Y.; Analysis and/or interpretation – X.N., F.W.; Literature search – S.Z., Xiaoli Zhang; Writing – X.N.; Critical review – X.N., Z.Y., Y.S., X.Y., Xiaoli Zhang, S.Z.

References

- 1.Ning X, Ye X, Si Y, Yang Z, Zhao Y, Sun Q, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation in patients with post-infarction left ventricular aneurysm:Analysis of 575 cases. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51:742–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Kimmenade RR, Januzzi JL., Jr Emerging biomarkers in heart failure. Clin Chem. 2012;58:127–38. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.165720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szücs A, Keltai K, Zima E, Vágó H, Soós P, Róka A, et al. Effects of implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation and shock application on serum endothelin-1 and big-endothelin levels. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103(Suppl 48):233S–6S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S233S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szabó T, Gellér L, Merkely B, Selmeci L, Juhász-Nagy A, Solti F. Investigating the dual nature of endothelin-1:ischemia or direct arrhythmogenic effect?Life Sci 2000. 66:2527–41. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00587-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vágó H, Soós P, Zima E, Gellér L, Keltai K, Róka A, et al. Changes of endothelin-1 and big endothelin-1 levels and action potential duration during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in dogs with and without ventricular fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(Suppl 1):S376–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts SW, Thakali K, Smark C, Rondelli C, Fink GD. Big ET-1 processing into vasoactive peptides in arteries and veins. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007;47:302–12. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolettis TM, Barton M, Langleben D, Matsumura Y. Endothelin in coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Cardiol Rev. 2013;21:249–56. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318283f65a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomaselli GF, Zipes DP. What causes sudden death in heart failure? Circ Res. 2004;95:754–63. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145047.14691.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fallavollita JA, Heavey BM, Luisi AJ, Jr, Michalek SM, Baldwa S, Mashtare TL, Jr, et al. Regional myocardial sympathetic denervation predicts the risk of sudden cardiac arrest in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilbert-Lampen U, Nickel T, Leistner D, Güthlin D, Matis T, Völker C, et al. Modified serum profiles of inflammatory and vasoconstrictive factors in patients with emotional stress-induced acute coronary syndrome during world cup soccer 2006. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tawa M, Yamamoto S, Ohkita M, Matsumura Y. Endothelin-1 and norepinephrine overflow from cardiac sympathetic nerve endings in myocardial ischemia. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:789071. doi: 10.1155/2012/789071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou S, Chen LS, Miyauchi Y, Miyauchi M, Kar S, Kangavari S, et al. Mechanisms of cardiac nerve sprouting after myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res. 2004;95:76–83. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000133678.22968.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao JM, Chen LS, KenKnight BH, Ohara T, Lee MH, Tsai J, et al. Nerve sprouting and sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2000;86:816–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuda K, Kanazawa H, Aizawa Y, Ardell JL, Shivkumar K. Cardiac innervation and sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2015;116:2005–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magyar J, Iost N, Körtvély A, Bányász T, Virág L, Szigligeti P, et al. Effects of endothelin-1 on calcium and potassium currents in undiseased human ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2000;441:144–9. doi: 10.1007/s004240000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Z, Xie Y, Wen H, Xiao D, Allen C, Fefelova N, et al. Role of the transient outward potassium current in the genesis of early afterdepolarizations in cardiac cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:308–16. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reisner Y, Meiry G, Zeevi-Levin N, Barac DY, Reiter I, Abassi Z, et al. Impulse conduction and gap junctional remodelling by endothelin-1 in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:562–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schou M, Gustafsson F, Corell P, Kistorp CN, Kjaer A, Hildebrandt PR. The relationship between n-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and risk for hospitalization and mortality is curvilinear in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng V, Kazanagra R, Garcia A, Lenert L, Krishnaswamy P, Gardetto N, et al. A rapid bedside test for b-type peptide predicts treatment outcomes in patients admitted for decompensated heart failure:A pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:386–91. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallstrom AP, McAnulty JH, Wilkoff BL, Follmann D, Raitt MH, Carlson MD, et al. Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillator (AVID) Trial Investigators. Patients at lower risk of arrhythmia recurrence:a subgroup in whom implantable defibrillators may not offer benefit. Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillator (AVID) Trial Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1093–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spieker LE, Noll G, Ruschitzka FT, Lüscher TF. Endothelin receptor antagonists in congestive heart failure:A new therapeutic principle for the future? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1493–505. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Omland T, Sloan S, Jarolim P, et al. Evaluation of multiple biomarkers of cardiovascular stress for risk prediction and guiding medical therapy in patients with stable coronary disease. Circulation. 2012;125:233–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Beneden R, Gurne O, Selvais PL, Ahn SA, Robert AR, Ketelslegers JM, et al. Superiority of big endothelin-1 and endothelin-1 over natriuretic peptides in predicting survival in severe congestive heart failure:A 7-year follow-up study. J Card Fail. 2004;10:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masson S, Latini R, Anand IS, Barlera S, Judd D, Salio M, et al. Val-HeFT investigators. The prognostic value of big endothelin-1 in more than 2,300 patients with heart failure enrolled in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT) J Card Fail. 2006;12:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang CL, Xie S, Qiao X, An YM, Zhang Y, Li L, et al. Plasma endothelin-1-related peptides as the prognostic biomarkers for heart failure:A prisma-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e9342. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012:The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]