Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States and worldwide.1 Despite recent advances in the treatment of the disease, the overall 5-year survival rate in the United States remains only 15%. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies are needed.

Historically, the histologic appearance of lung cancer has been used to guide treatment decisions, primarily distinguishing patients with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) from those with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Three major subtypes of NSCLC—adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma—were grouped together as a single entity for therapy and enrollment of patients onto clinical trials. With the recent regulatory approval of pemetrexed specifically for adenocarcinoma and large-cell carcinoma,2 and bevacizumab for nonsquamous NSCLC,3 the discrimination of specific NSCLC subtypes has grown in significance.

During the past 5 years, it has also become evident that adenocarcinomas have distinct genomic changes that allow them to be further classified into clinically relevant molecular subsets. Each subset can be defined by a specific genomic alteration that is responsible for both the initiation and maintenance of the lung cancer (ie, a driver mutation). Importantly, specific mutations induce differential sensitivity of tumors to targeted therapeutic agents. For example, tumors highly sensitive to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; ie, gefitinib or erlotinib) often contain dominant somatic mutations in exons that encode a portion of the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR.4–6 Conversely, tumors with somatic mutationsin KRAS, which encodes GTPase downstream of EGFR, display primary resistance to these drugs.7,8

When knowledge of specific genetic changes is linked to a targeted therapy, dramatic improvements in response and clinical benefit can be observed without the need for initial treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy. For example, in the phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib compared with carboplatin plus paclitaxel in never or light East Asian smokers with advanced NSCLC (ie, the Iressa Pan Asia Study [IPASS]), patients with EGFR-mutant tumors experienced longer progression-free survival with gefitinib, and patients without mutations had longer progression-free survival with chemotherapy(EGFR mutation positive: hazard ratio = 0.48;95%CI, 0.36 to 0.64; P < .0001 [favors gefitinib]; EGFR mutation negative: hazard ratio = 2.85; 95% CI, 2.05 to 3.980; P < .0001 [favors chemo-therapy]).9 Thus, gefitinib is a reasonable first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer.

In 2007, Soda et al10 identified another potential driver mutation in NSCLC—fusion of the N-terminal portion of the protein encoded by the echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) gene with the intracellular signaling portion of the receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene. These fusions are the result of inversions within the short arm of chromo-some 2 (involving 2p21 and 2p23, approximately 12 Mb apart). Whereas other genetic alterations involving ALK have been identified in anaplastic large-cell lymphomas,11 inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors,12 and neuroblastomas,13–15 none have yet been found in lung cancers.16,17 The EML4-ALK fusion gene seems to be novel to NSCLC.18,19

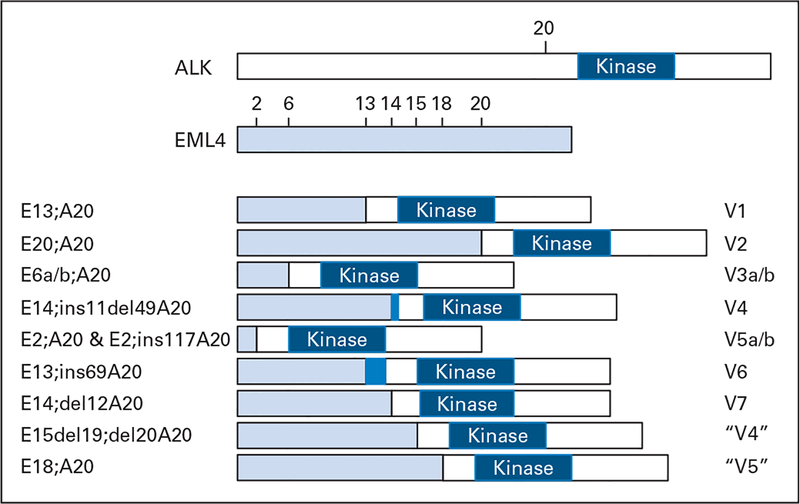

To date, multiple EML4-ALK variants have been identified in lung cancer (Fig 1).10,19–23a Although the fusions contain variable truncations of EML4 (occurring at exons 2, 6, 13, 14, 15, 18, and 20), the ALK fusion in all of them starts at a portion encoded by exon 20 of the kinase gene. To date, all EML4-ALK fusions tested biologically demonstrate gain of function properties.10,20,22

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of EML4-ALK translocations in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Multiple EML4-ALK variants (V1 to V7) have been identified in NSCLCs. All involve the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) starting at a portion encoded by exon 20. EML4, however, is variably truncated. Variant 1 fuses exon 13 to ALK10; variant 2 fuses exon 2010; variants 3a and 3b fuse exon 6a and 6b, respectively20; variant 4 fuses exon 14 (with an additional 11 nucleotides of unknown origin [dark blue] and starting at nucleotide 50 in exon 20)19; variants 5a and 5b fuse exon 2 (with 5b containing an additional 117 nucleotides from intron 19)19; variant 6 fuses exon 13 (with an additional 69 nucleotides from intron 19 [dark blue])22; and variant 7 fuses exon 14 (starting at nucleotide 13 in exon 20).22 Additional variants have been reported as V4, fusing exon 15 (minus 19 nucleotides and starting at nucleotide 21 in exon 20),21 and V5, fusing exon 18.23 The nomenclatures used in the literature are depicted on the right. On the left is another potential nomenclature, slightly modified from that of Hiroyoki Mano (see http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Tumors/inv2p21p23NSCCLunglD5667.html).

How frequent are ALK fusions in lung cancer? Are there clinical characteristics unique to patients whose tumors harbor ALK fusions? Previous studies, mostly involving East Asian patients, have reported that 3% to 7% of lung tumors harbor EML4-ALK fusions (Table 1). Multiple histologic subtypes of NSCLC have been tested, but adenocarcinomas seem to be the major NSCLC cell type harboring EML4-ALK fusions. Preliminary data also indicate a significant relationship between smoking and EML4-ALK positivity, with the fusions more commonly found in light smokers (< 10 pack years) or never smokers.21,23,24 EML4-ALK fusions have also been associated with a lack of EGFRorKRASmutations,16,23–26youngerage,23–25andadenocarcinomas with acinar histology.24,25

Table 1.

Studies Evaluating EML4-ALK Positivity in Lung Cancer Patients

| Study | No. of Patients | Ethnicity of Patients |

EML4- ALK- Positive Patients |

Detection Method |

Clinical Associations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |||||

| Soda et al10; NSCLC | 75 | Japanese | 5 | 7 | RT-PCR | No EGFR/KRAS mutations |

| Inamura et al25 | Japanese | RT-PCR | AD; acinar histology (variant 2); no EGFR/KRAS mutations | |||

| Total | 221 | 5 | 2 | |||

| AD | 149 | 5 | 3 | |||

| SQ | 48 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LC | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SCLC | 21 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Takeuchi et al19 | Japanese | Multiplex RT-PCR | AD; not in 292 other cancer types | |||

| Total | 364 | 11 | 3 | |||

| AD | 253 | 11* | 4 | |||

| ADSQ | 7 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SQ | 71 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LC | 7 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LCNE | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| PLEO | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SCLC | 22 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Inamura et al24 | 11* | Japanese | NA | NA | Acinar histology; less differentiated; younger age; smaller size; never/light smokers; no EGFR/KRAS mutations |

|

| Perner et al28; NSCLC | 603 | Swiss (n = 507) and American (United States; n = 96) |

16 | 3 | FISH | NA |

| Koivunen et al21; NSCLC | 305 | 8 | 3 | RT-PCR | AD; never/light smokers; no KRAS/BRAF mutations | |

| United States | 138 | American (United States) | 2 | 1 | (1 overlapping EGFR mutation) | |

| Korea | 167 | Korean | 6 | 4 | ||

| Shinmura et al16; NSCLC | 77 | Japanese | 2 | 3 | RT-PCR | Adenocarcinoma; former smokers; no EGFR/KRAS/PIK3CA mutations |

| Martelli et al26; NSCLC | 120 | European | 9 | 8 | RT-PCR | No EGFR mutations (1 overlapping KRAS mutation) |

| Wong et al23; NSCLC | 266 | Chinese | 13 | 5 | RT-PCR | AD; female sex; never/light smokers; younger age; no |

| AD | 209 | 11 | 5 | EGFR/KRAS mutations | ||

| SQ | 34 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LEL | 11 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Other | 12 | 2 | 17 | |||

| Shaw et al27; enriched | 141 | 19 | 13 | FISH, IHC | AD; male sex; never/light smokers; younger age; no | |

| NSCLC | EGFR/KRAS mutations | |||||

| AD | 130 | 18 | 14 | |||

| ADSQ | 4 | 1 | 25 | |||

| SQ | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LC/NOS | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer, RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; AD, adenocarcinoma; SQ, squamous cell carcinoma; LC, large-cell carcinoma; SCLC, small-cell lung carcinoma; ADSQ, adenosquamous cell carcinoma; LCNE, large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; PLEO, pleomorphic carcinoma; NA, not applicable; FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; LEL, lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Positive patients were identified from a prior study conducted by same group. Note that not all tumors were tested for all known EML4-ALK variants.

Importantly, lung cancers that harbor genomic ALK alterations may be clinically responsive to pharmacologic ALK inhibition. Just as treatment of lung cancer cells bearing drug-sensitive EGFR mutations with EGFR TKIs can lead to growth inhibition and cell death, treatment of tumor cells containing EML4-ALK fusions with ALK kinase inhibitors can lead to the potent suppression of downstream survival signaling pathways and an apoptotic response.10,21,29 Furthermore, in an EML4-ALK mouse lung tumor model, treatment with an ALK inhibitor resulted in reduced tumor burden compared with controls.30 Several novel selective inhibitors of ALK kinase are currently in preclinical or early clinical testing,31 including one compound, PF-02341066, which is a dual MET/ALK inhibitor. Preliminary data from a phase I trial of PF-02341066 presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting this year reported one partial response, two unconfirmed partial responses, and four patients with stable disease among 10 patients with EML4-ALK–positive NSCLC. The most common toxicities were nausea, emesis, fatigue, and diarrhea.32 An expanded cohort of the same trial including 13 patients with NSCLC, eight of whom were evaluable for response, reported six partial responses and one stable disease as the best response.32

In this issue of Journal of Clinical Oncology, Shaw et al27 confirm and extend our knowledge about the clinical features and outcomes of EML4-ALK–positive lung cancer in a North American population. In their study, for tumors to be analyzed for EML4-ALK fusions, they required that patients have two or more characteristics commonly associated with patients who have EGFR-mutant NSCLCs (ie, female sex, Asian ethnicity, history of no or light smoking, and adenocarcinoma histology). By using these criteria, they were able to enrich for positive tumors (13% of total analyzed). In 141 patients, 94% of whom were non-Asian, they found EML4-ALK fusions to be associated with younger age, male sex, minimal smoking exposure, and adenocarcinoma histology. Thirty-one percent of specimens had acinar growth patterns, and 61% had a solid growth pattern. EML4-ALK fusions were not found in tumors with EGFR or KRAS mutations. Remarkably, in never/light smokers without EGFR mutations, EML4-ALK fusions were found in 33% of patients. They further demonstrate thatEML4-ALKpositivityisassociatedwithresistanceto EGFR TKIs. Additionally, compared with patients whose tumors harbor neither EML4-ALK nor EGFR mutations, they showed that patients whose tumors harbor EML4-ALK display similar sensitivity to platinum-based combination chemotherapy and no differences in overall survival.

Currently, a major issue is defining the best way to assess for the presence of ALK fusions in lung tumors. A variety of methods have been used, including immunohistochemistry, fluorescent in situ hybridization, and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. None of the assays have proven to be easily adopted by diagnostic molecular pathology laboratories. ALK antibodies seem to give variable results.24,26 Fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis involves use of two differently labeled break-apart probes on opposite sides of the breakpoint of the ALK gene; normal ALK appears as a yellow signal, whereas rearranged ALK at this locus results in separate red and green signals.28 However, these signals can be difficult to interpret. Finally, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction requires good-quality mRNA. Moreover, because fusions can occur at multiple points (Fig 1), multiple polymerase chain reaction primers are required to detect all known fusion transcripts. The variability of tumors testing positive in the literature is likely a result of the different methods of detection used in the various studies. Future efforts are needed to determine the optimal method for routine diagnostic detection of ALK fusions in lung cancers.

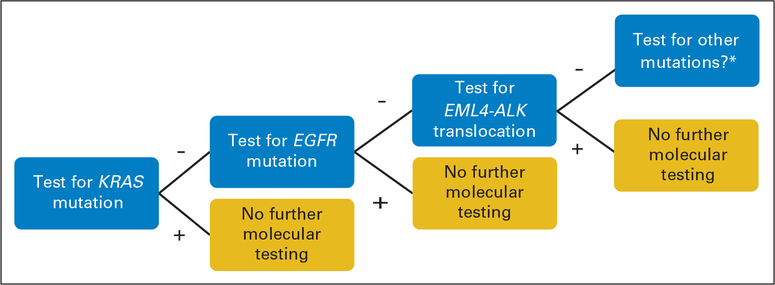

How should we find appropriate patients for treatment? One approach is to use clinical criteria to enrich for potential responders. However, clinical criteria can be misleading; for example, the first EML4-ALK fusion was found in a former smoker, not a light/never smoker.10Analogously,KRASmutationsareassociatedwithsmoking, but 15% of never smokers have tumors that harbor mutant KRAS.34 Thus, we favor development of robust platforms for molecular diagnostic testing of lung adenocarcinomas. Ideally, tumors would be simultaneously tested for the three most common lesions to date–KRAS, EGFR, and ALK fusions. However, an alternative stepwise approach (Fig 2) is to test lung adenocarcinomas first for KRAS mutations because 15% to 30% of tumors harbor such alterations. If a tumor is positive for a KRAS mutation, no further molecular testing is required. Treatment recommendations would include KRAS-directed therapy (when it is developed); an EGFR TKI would be lower priority compared with other available treatments. (The sensitivity of KRAS-mutant tumors to ALK inhibitors remains to be established.) If the tumor is negative, it would be tested for EGFR mutations, which are found in approximately 10% of tumors. If the tumor is positive for an EGFR mutation, an EGFR TKI would be recommended. If negative, the tumor would be assessed for ALK translocations. If positive, treatment would include an ALK inhibitor; again, an EGFR TKI would be lower priority. If negative, then these triple-negative tumors should be considered for analysis of rarer mutations (eg, in BRAF, MEK1, AKT1, PIK3CA, and so on) and/or intensive research to identify new driver mutations.

Fig 2.

Suggested algorithm for molecular testing for patients with non–small-cell lung cancer with tumors of adenocarcinoma histology before treatment with oral targeted therapy. (*) “Other” includes BRAF, MEK1, AKT1, PIK3CA, and so on.

In summary, the work by Shaw et al27 as well as multiple other groups regarding EML4-ALK validates the fusions as defining a distinct molecular subset of NSCLC. The promise of ALK inhibitors against these fusions brings us one step closer to personalized lung cancer therapy, in which patients are treated not empirically with cytotoxic chemotherapy but with targeted agents according to the genetic makeup of their tumors.

Acknowledgment

Supported in part by Grant No. CA90949 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Lung Cancer and Grant No. CA68485 from the NCI Cancer Center Core.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: William Pao, MolecularMD (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. : Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 58:71–96, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. : Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:3543–3551, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. : Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 355:2542–2550, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. : Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 350:2129–2139, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. : EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 304:1497–1500, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, et al. : EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:13306–13311, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. : Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in non–small-cell lung cancers treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol 23:5900–5909, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, et al. : KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med 2:e17, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok T, Wu Y-L, Thongprasert S, et al. : Phase III, randomised, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib vs carboplatin / paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 19:viii1, 2008. (abstr LBA2) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. : Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 448:561–566, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris SW, Kirstein MN, Valentine MB, et al. : Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Science 267:316–317, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: Comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol 31:509–520, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Takita J, Choi YL, et al. : Oncogenic mutations of ALK kinase in neuroblastoma. Nature 455:971–974, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George RE, Sanda T, Hanna M, et al. : Activating mutations in ALK provide a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Nature 455:975–978, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Lequin D, Brugieres L, et al. : Somatic and germline activating mutations of the ALK kinase receptor in neuroblastoma. Nature 455:967–970, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinmura K, Kageyama S, Tao H, et al. : EML4-ALK fusion transcripts, but no NPM-, TPM3-, CLTC-, ATIC-, or TFG-ALK fusion transcripts, in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Lung Cancer 61:163–169, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, et al. : Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 455:1069–1075, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuyoshi Y, Inoue H, Kita Y, et al. : EML4-ALK fusion transcript is not found in gastrointestinal and breast cancers. Br J Cancer 98:1536–1539, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Soda M, et al. : Multiplex reverse transcription-PCR screening for EML4-ALK fusion transcripts. Clin Cancer Res 14:6618–6624, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi YL, Takeuchi K, Soda M, et al. : Identification of novel isoforms of the EML4-ALK transforming gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 68:4971–4976, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koivunen JP, Mermel C, Zejnullahu K, et al. : EML4-ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14:4275–4283, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Togashi Y, et al. : KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15:3143–3149, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong DW, Leung EL, So KK, et al. : The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer 115:1723–1733, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, et al. : Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell 131:1190–1203, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, et al. : EML4-ALK lung cancers are characterized by rare other mutations, a TTF-1 cell lineage, an acinar histology, and young onset. Mod Pathol 22:508–515, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, et al. : EML4-ALK fusion is linked to histological characteristics in a subset of lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol 3:13–17, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martelli MP, Sozzi G, Hernandez L, et al. : EML4-ALK rearrangement in non-small cell lung cancer and non-tumor lung tissues. Am J Pathol 174:661–670, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. : Clinical features and outcome of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer harboring EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perner S, Wagner PL, Demichelis F, et al. : EML4-ALK fusion lung cancer: A rare acquired event. Neoplasia 10:298–302, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDermott U, Iafrate AJ, Gray NS, et al. : Genomic alterations of anaplastic lymphoma kinase may sensitize tumors to anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res 68:3389–3395, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soda M, Takada S, Takeuchi K, et al. : A mouse model for EML4-ALK-positive lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:19893–19897, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galkin AV, Melnick JS, Kim S, et al. : Identification of NVP-TAE684, a potent, selective, and efficacious inhibitor of NPM-ALK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:270–275, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwak EL, Camidge DR, Clark J, et al. : Clinical activity observed in a phase I dose escalation trial of an oral c-Met and ALK inhibitor, PF-02341066. J Clin Oncol 27:15s, 2009. (suppl; abstr 3509) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw AT, Costa DB, Iafrate AJ, et al. : Clinical activity of the oral ALK and MET inhibitor PF-02341066 in non-small lung cancer (NSCLC) with EML4-ALK translocations. Presented at the 13th World Congress on Lung Cancer, San Francisco, CA, July 31-August 4, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riely GJ, Kris MG, Rosenbaum D, et al. : Frequency and distinctive spectrum of KRAS mutations in never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 14:5731–5734, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]