Abstract

Cephalosporins are commonly used antibiotics both in hospitalized patients as well as outpatients. Hypersensitivity reactions to cephalosporins are becoming increasingly common with a wide range of immunopathologic mechanisms. Cephalosporins are one of the leading causes for perioperative anaphylaxis and severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Patients allergic to cephalosporins tend to tolerate cephalosporins with disparate R1 side chains but may react to other beta-lactams with common R1 side chains. Skin testing for cephalosporins has not been well-validated but appears to have a good negative predictive value for cephalosporins with disparate R1 side chains. In vitro tests including basophil activation tests have lower sensitivity when compared to skin testing. Rapid drug desensitization procedures are safe and effective and have been utilized successfully for immediate and some nonimmediate cephalosporin reactions. Many gaps in knowledge still exist regarding cephalosporin hypersensitivity.

Keywords: cephalosporin, penicillin, allergy, betalactam, cross-reactivity, skin test, anaphylaxis

Introduction

Cephalosporins are amongst the most commonly used antibiotics for hospitalized patients in the U.S. and the most common antibiotic class patients receive at discharge.(1) In Europe, cephalosporins represent 11.4% of total outpatient antibiotics and their use has increased over time.(2) Cephalosporins can cause a broad range of hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) of differing immunopathology. This article will focus on our current understanding of cephalosporin hypersensitivity with special emphasis on immediate reactions to cephalosporins and current approaches to delabeling patients.

Cephalosporin Allergy Epidemiology

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) to cephalosporins are reported by 1.3% to 1.7% of U.S. patients, with a prevalence that has been generally consistent over the last twenty years.(3, 4)The incidence of cephalosporin ADRs was determined to be 0.80% for oral cephalosporins and 0.64% for parenteral cephalosporins in one large U.S. health plan.(5) Among inpatient allergic drug reactions in one U.S. hospital, a cephalosporin was the culprit drug in 4.3% in one study and 6.9% in another study.(6, 7)

Women report cephalosporin ADRs 2 to 3-fold more often than men.(3, 5) Multiple drug intolerance syndrome (MDIS) and multiple drug allergy syndrome (MDAS) are associated with cephalosporin reactions, with approximately 15% of MDIS and MDAS patients counting cephalosporins as one of their culprit drug classes.(8)

The cephalosporin with the highest ADR prevalence in one large northeastern U.S. patient population was cephalexin (0.6%).(3) Third generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone) and second generation cephalosporins were the third and fourth most common drug groups causing ADRs in a South Korean study of hospitalized patients.(9) Ceftaroline, a newer “5th generation” parenteral cephalosporin often restricted for severe and resistant infections, has a high reported ADR incidence (up to 1 in 5).(10)

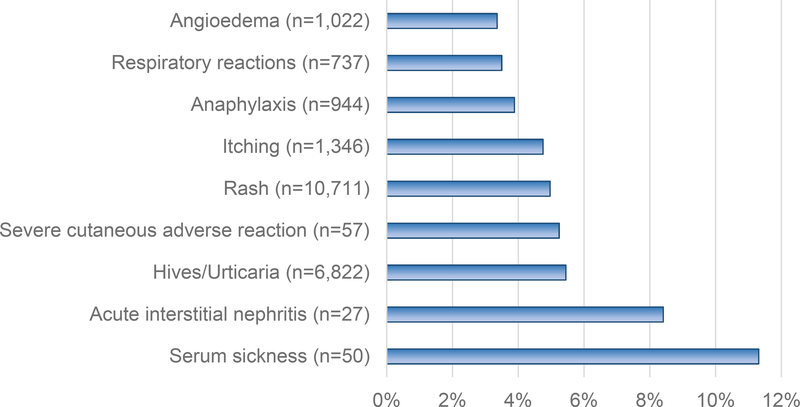

Cephalosporins can cause all HSR types, but the most commonly reported reaction is rash.(4) There were 27 cutaneous allergic reactions to cephalosporins among 1,781 patients (1.5%; 95%CI 0.9 to 2.1%) identified in a systematic review that included prospective data from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program.(11) Cephalosporins were the causative drug class for 4% of “rash” and 5% of “hives” listed in a U.S.-based electronic heath record analysis.(12, 13) That analysis also identified cephalosporins as the causative drug class for 11% of all serum sickness like reactions, 9% of all acute interstitial nephritis, and 2.5% of angioedema reactions (Figure 1).(12, 13)

Figure 1. Cephalosporin HSRs.

This figure demonstrates the proportion of each reported HSR in the electronic health record allergy module attributed to a cephalosporin antibiotic (X-axis), as determined by a large U.S. healthcare system analysis that included 4,017,708 reactions reported by 2,734,506 patients.(12) The HSRs are on the Y-axis, with the total number of HSRs attributed to cephalosporin antibiotics displayed in parentheses.

Cephalosporin anaphylaxis incidence was 5 in 901,908 courses of oral cephalosporins and 8 in 487,630 courses for parenteral exposures in one large U.S.-based health plan.(5) The approximate incidence of electronic health record (EHR)-documented cephalosporin anaphylaxis in another U.S. health system was 6.1 in 10,000 patients.(14) Of 1,756,481 patients with an EHR-report of drug-induced anaphylaxis, 1,078 (6.1%) had anaphylaxis documented from a cephalosporin antibitoic.(14) The most common cephalosporin anaphylaxis culprits in that population included cephalexin (1.1% of documented drug-induced anaphylaxis) and cefaclor (0.8% of documented drug-induced anaphylaxis).(14) Cefazolin is the most common cause of perioperative anaphylaxis in the U.S.(15–17)

Cephalosporins were the drug class reported to cause severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR) in 5% of possible SCAR cases identified in the EHR allergy list.(12, 13) In another U.S. study covering over 900,000 patients exposed to over 1 million cephalosporins, there were only three cephalosporin-associated SCARs, and those three patients were also on other medications that also could have caused the SCAR.(5) In the largest U.S.-based cohort of validated Drug Reaction Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome patients (n=69), 38 had a known single causative drug and cephalosporins were the known culprits in 5 patients (13%).(18) Of antibiotic-induced SCARs reported to the Food and Drug Administration’s adverse event reporting system from 2004 through 2018, ceftriaxone was the 3rd most common DRESS syndrome culprit (591 reported cases) and 5th most common Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis culprit (598 reported cases) (Unpublished data, Liqin Wang, PhD and Li Zhou, MD, PhD).

Immunopathology of Cephalosporin Allergy

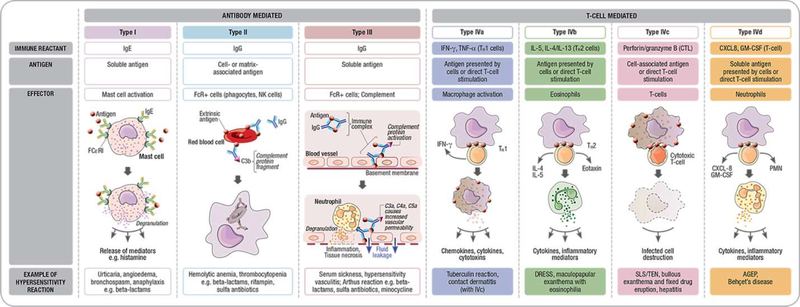

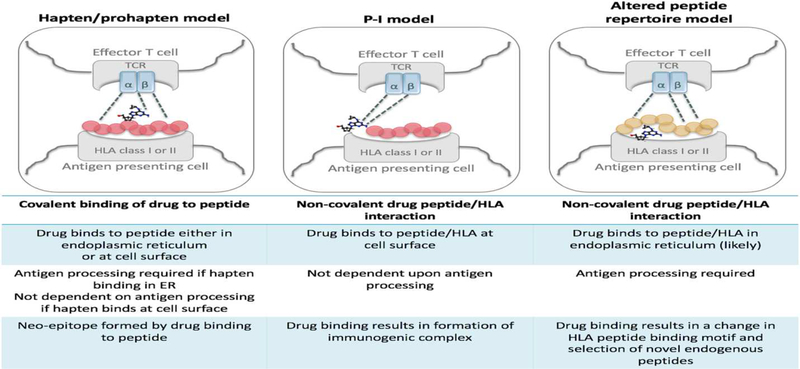

Like most other drugs, cephalosporins are small molecules that are not independently capable of causing an allergic reaction.(19, 20) An immune classification system provides a framework for mechanistically understanding the differing clinical phenotypes of cephalosporin reactions and models have been proposed to explain how small molecules activate immune responses (Figures 2 and 3).(19, 20) Cephalosporins, like penicillins, are prevalent causes of both immediate and delayed HSR phenotypes.(21) Under physiological conditions, the beta-lactam ring is unstable and in the case of penicillins results in the generation of major and minor determinants that covalently bind to host proteins which have been well defined and used as testing strategies in clinical practice.(22) The specific antigenic determinants of beta-lactam allergy have been studied most extensively in the context of IgE-mediated reactions where it has been previously elucidated that the antigenic determinant is predicated on the entire beta-lactam and protein carrier molecule and differences in the class specific side chain and R1 and R2 side chains provide the antigen specificity.(22, 23) Unlike penicillins where the determinants are stable and identifiable, determinants have not been reliably defined for cephalosporins and the speed and efficiency by which cephalosporins form hapten-protein conjugates is comparatively inferior to penicillins.(24) Cephalosporins differ from penicillins by both their 6-membered dihydrothiazine ring and the presence of an R2 group.(21) Some evidence supports that the opening of the beta-lactam ring destroys the R2 side chain and leads to unstable conjugates and fragmented poorly identified determinants.(25, 26) Although IgE antibodies can theoretically bind to the beta-lactam ring, the protein carrier molecule and side chains, it may be that the R1 side chain and the remaining beta lactam moiety covalently linking to host proteins is central to immunogenicity. This hypothesis is supported by in vitro as well as clinical data that will be discussed later in the section on cross-reactivity.

Figure 2: Immunological classification:

Modified Gel Coombs classification of Antibody mediated and delayed T-cell mediated reactions: Cephalosporins are associated with the full spectrum of reactions from Type I - anaphylaxis – IgE mediated; Type II – hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, type III (serum sickness and vasculitis) as well as full spectrum of T-cell mediated reactions (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, maculopapular eruption, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, fixed drug eruption, hepatitis and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.

Figure 3: Models of Immune Activation.

The hapten-prohapten model shows the drug covalently binds to a peptide either intracellularly in the endoplasmic reticulum prior to peptide processing and presentation or at the cell surface. The pharmacological interaction model (p-i) shows the drug non-covalently binding to the HLA-molecule and/or T-cell receptor to result in direct T-cell activation. The altered peptide repertoire model shows a drug binding non-covalently in the HLA antigen binding cleft that alters the repertoire of self-peptide ligands leading to presentation of novel peptide ligands that are recognized as foreign and elicit an immune response. TCR – T-cell receptor.

Pharmacogenetics of Cephalosporin Allergy

Discovery of new human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations and drug hypersensitivity syndromes has been particularly impactful over the last 2 decades in both improving drug safety and our understanding of the immunopathogenesis of these reactions.(19, 27–31) HLA associations with drug hypersensitivity reactions have not yet been described for the majority of antimicrobials including beta-lactams. The most significant associations to-date have been described between penicillins and drug-induced liver disease (DILI).(28–30) For both flucloxacillin (available in Europe and Australia) and amoxicillin-clavulanate, the rarity of the DILI in relation to how commonly these drugs are used has precluded translation of HLA use in screening. There is currently not thought to be any cross-reactivity with other beta-lactams for DILI associated with either amoxicillin-clauvulanate or flucloxacillin.(32) Another recent study found an association between the haplotype HLA-DQA1*01:04/DQB1*05:03/DRB1*14:05 and drug and non-drug induced interstitial nephritis.(33) The specific relevance of this haplotype for beta-lactam associated acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is not known. Although semi-synthetic penicillins are relatively common causes of AIN, it is common for these patients to tolerate cephalosporins such as cefazolin.(34, 35)

To date there have been few studies that have associated variation in HLA and immediate reactions. The only HLA allele that has been significantly associated with drug-induced anaphylaxis is HLA-DRB1*07:01 in association with asparaginase immediate reactions.(36) There have been no studies that have been powered to specifically examine genetic risk factors for cephalosporin allergy. In particular for IgE-mediated reactions where sensitivity will wane significantly over time and almost 80% of cephalosporin allergic individuals have lost skin-test reactivity to the implicated drug by 5 years after the acute reaction it is assumed that HLA may be necessary but not sufficient and subject to other ecologic and epigenetic factors.(21, 35) Candidate gene studies for beta-lactam allergy have demonstrated strongest associations with genetic variation in HLA class II antigen presenting genes, NOD2 genes affecting class II expression, genes in involved in IgE synthesis (STAT6, IL4RA, IL13), expression of pre-formed mediators (LGALS3) and cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, IL-18).(37, 38) For beta-lactams a genome wide association study showing a signal in the class II HLA region did not reach genome wide significance.(39)

Clinical Presentations including Cefazolin in Perioperative Anaphylaxis

Cephalosporins are capable of causing HSRs ranging from benign exanthema to anaphylaxis or SCAR. Maculopapular exanthema are the most common form of delayed reactions. Serum sickness-like reactions (SSLR) may occur with many cephalosporins but cefaclor has the highest relative risk for causing SSLR and in some series may represent > 80% of antibiotic-associated SSLR.(40) The mechanism for cefaclor SSLR appears related to the production of toxic metabolites and may have a pharmacogenetic basis but this has not been adequately explored.(41) While published data are limited, children with SSLR to cefaclor appear to tolerate other cephalosporins.(40) Cephalosporins are also a common cause of antibiotic-associated SCAR.(42)

HSRs during the perioperative period are unpredictable and can be life threatening. Incidence of perioperative HSRs is likely underreported but ranges in the literature from 1:1380 to 1:20,000.(43–45) The main etiological agents of perioperative anaphylaxis are antibiotics and neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) but this varies between countries. In the U.S., antibiotics are the most frequent cause of HSRs in the operating room, accounting for 50% of IgE-mediated perioperative HSRs.(15, 16) Cefazolin, the first-line indicated perioperative antibiotic for most operations, has been reported in several studies as the most common causative agent of perioperative anaphylaxis in the U.S. and some other countries.(16, 17, 46, 47)

Cephalosporin Cross-Reactivity with Other Beta-Lactams

Patients with cephalosporin allergy appear to be at higher risk for a reaction to other beta-lactam antibiotics because of shared chemical structures (beta-lactam ring, R group side chains).(48) However, patients with any reaction to a drug are at a higher risk of having another reaction to a drug,(8) and patients determined to be allergic based on reactive skin tests are not confirmed allergic with drug challenge in allergy practice (because of valid safety concerns).(49) Thus, precise cross-reactivity estimates remain unknown to date.

In a study of 24 patients with cephalosporin reaction histories (and a positive serum-specific IgE to cephalosporin), 2 patients (8.3%; 95%CI 2.3% to 25.8%) had positive skin tests to penicillin.(50) In a study of 98 patients with well-characterized IgE-mediated cephalosporin allergy histories and positive cephalosporin skin tests, 25 patients (25.5%; 95%CI 17.9% to 35.0%) had positive tests to penicillins (11 with positive skin tests and 14 had only serum-specific IgE to penicillin determinants positive).(48) Among 34 hospitalized patients with cephalosporin allergy histories (not confirmed with testing) who received a 2-step graded challenge to penicillins, 2 patients (5.9%; 95%CI 0.7% to 19.7%) had a hypersensitivity reaction.(51) It thus appears that cross-reactivity is likely less than 10%; reactions are likely to be even lower in those who are unlikely to be allergic and when the cephalosporin challenged does not share the R1 group. The generally low rate of clinical cross-reactivity observed between penicillins and cephalosporins that do not share the same R1 group, for both IgE and other antibody mediated and T-cell mediated reactions, further supports the antigen specificity of cephalosporin reactions.(52)

In the cohort of 98 cephalosporin allergic patients, 1 patient (1.0%, 95%CI 0.0% to 3.0%) had positive skin tests to both imipenem and meropenem.(50) Among 15 hospitalized patients with cephalosporin allergy histories including 3 with severe IgE histories (not confirmed with testing) who received a 2-step graded challenge to carbapenems, 1 patient (6.7%; 95%CI 0.2% to 32.0%) had a hypersensitivity reaction; supporting the idea of infrequent cross-reactivity between cephalosporins and carbapenems.(51)

Aztreonam is less immunogenic than other beta-lactams.(53) Patients with an allergy to cephalosporins can receive aztreonam (a monobactam and beta-lactam) without any concern of cross-reactivity, except if the cephalosporin allergy is to ceftazidime, because ceftazidime and aztreonam share a common R1 side chain that can result in cross-reactive allergic reactions. However, in the 98 patients with well-characterized severe IgE-mediated cephalosporin allergy histories, 3 patients were (3.1%; 95%CI 1.0% to 8.6%) skin test positive to aztreonam; the remaining 95 (96.9%) tolerated aztreonam challenges.(48)

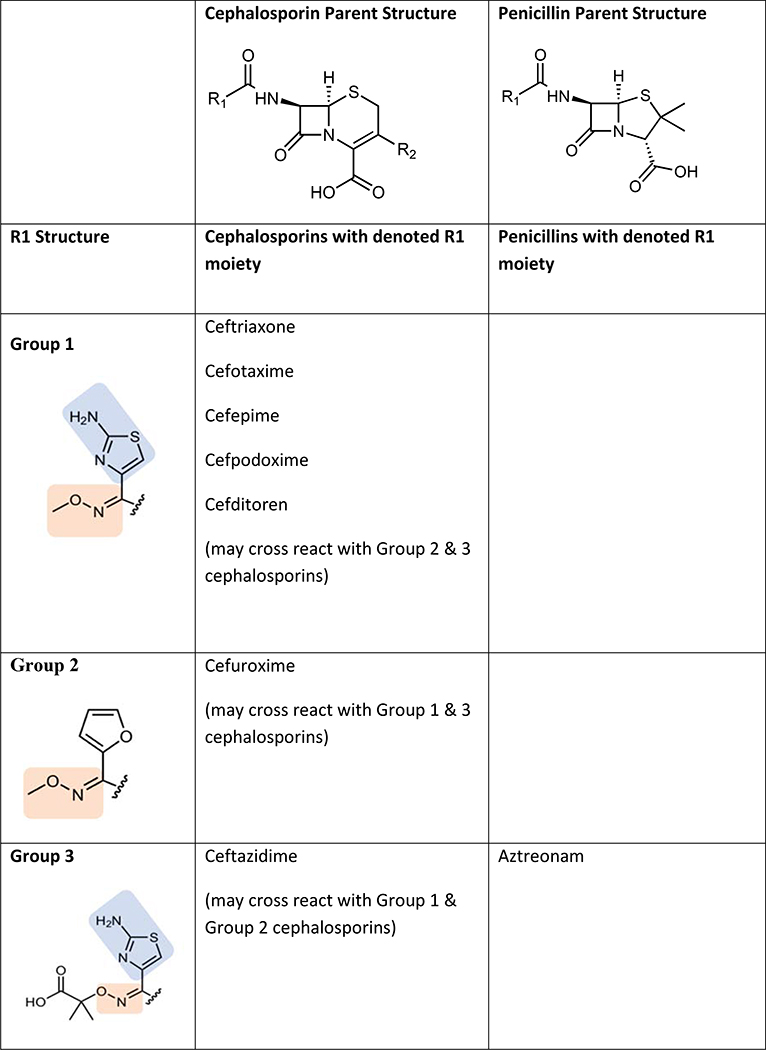

Cross-Reactivity Amongst Cephalosporins

Several studies have suggested that cephalosporin allergic subjects most often tolerate other cephalosporins with disparate R1 group side chains. The largest study to date from Romano et al. evaluated 102 subjects (89 with anaphylactic histories) from Italy with immediate reactions to cephalosporins who underwent skin testing to alternative cephalosporins.(54) They divided subjects into 4 groups based on the pattern of skin test reactions. Group A patients (71% of subjects) had hypersensitivity to Group A cephalosporins sharing a common R1 methoxyamino group and included ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, cefepime, cefodizime, and ceftazidime. Group B patients (13%) had hypersensitivity to Group B cephalosporins sharing a common R1 amino group (also shared by amoxicillin and ampicillin) and included cefaclor, cephalexin, and cefadroxil. Group C patients (7%) had hypersensitivity to Group C cephalosporins that have unique R1 groups that are structurally unrelated to other cephalosporins and included cefazolin, cefamandole, cefoperazone, and ceftibuten. Group D subjects (9%) appeared to cross-react amongst groups with skin test reactivity to 2 or more of groups A, B, and C. Ceftriaxone was the culprit cephalosporin in 60% of all patients followed by cefaclor (11.6%) and ceftazidime (8.9%). All 102 subjects tolerated 326 challenges to other cephalosporin groups that were skin test negative. This study therefore suggests that 91% of cephalosporin allergy is based on side-chain structure (Groups A, B, and C) and that a negative skin test to an alternative cephalosporin with a dissimilar R1 side chain predicts tolerance. Other studies have confirmed side chain specificity in patients with histories of anaphylaxis to cefazolin (cumulative total of 36 patients) who have been shown to have negative skin tests and challenges to cephalosporins with different R1 side chains including cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and cefalotin.(47, 55, 56) Cefazolin has a relatively unique R1 side chain, however ceftezole (available in Asia but not the U.S.) has an identical R1 chain and anaphylaxis has been reported to this drug.(57) Proposed cross-reactivity patterns amongst cephalosporins is shown in Figure 4. Whether this same pattern of cross-reactivity occurs in other countries, particularly the U.S. where side chain specific aminopenicillin reactions are rare, is unknown. Overall, tolerance to cephalosporins can usually but not always be predicted based on similarities or differences in R1 side chains between the cephalosporins. Confirming tolerance requires a drug challenge.

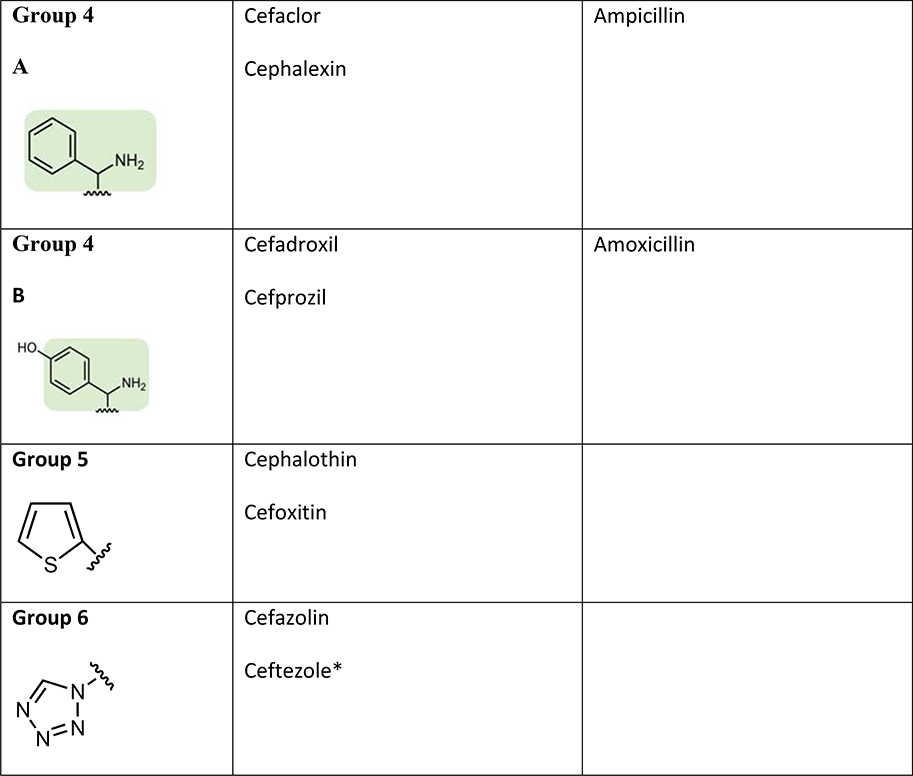

Figure 4: Sharing of R1 side chains between cephalosporins and other beta-lactams.

Cephalosporin immunogenicity and cross-reactivity appears to be largely dictated by R1 side chains. The group numbers have been labeled for the purpose of illustrating differing R1 side chains. Colored shading represents shared structures with clinical cross-reactivity described. The R1 side chain chemical structure names are: Group 1 (2-amino-N-methoxythiazole-4-carbimidoyl); Group 2 (N-methoxyfuran-2-carbimidoyl); Group 3 ((E)-2-((((2-aminothiazol-4-yl)methylene)amino)oxy)-2-methylpropanoic acid); Group 4A (phenylmethanamine); Group 4B (4-(aminomethyl)phenol); Group 5 (thiophene); Group 6 (tetrazole)

*Ceftezole is not available in the U.S.

Diagnosis of Cephalosporin Allergy

Similar to evaluation of other drug allergic patients, a careful history is crucial in determining the optimal diagnostic testing strategy. Diagnostic tests differ between those with immediate versus delayed reactions to cephalosporins.

Skin Testing

Immediate Reactions

Relatively few studies have evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of cephalosporin skin tests in patients with immediate reactions to cephalosporins. Antunez et al. evaluated 127 adult and pediatric patients from Spain over a 4-year period with a history suggestive of an immediate reaction to cephalosporins using skin tests, in vitro tests, and drug challenge.(50) Fifty-one cases (40.1%) were confirmed as allergic with 76.4% positive by skin tests, 5.9% with negative skin tests and positive radioallergosorbent test (RAST), and 17.6% with negative skin and RAST but positive cephalosporin challenge. Romano et al. studied 76 patients over an 8-year period at 2 allergy clinics in Italy.(58) Most patients (77%) had histories of anaphylaxis with the remaining urticaria/angioedema. The mean time since the index reaction was 24 months. Skin and RAST were performed to injectable and oral cephalosporins with skin test concentrations of 2 mg/ml. Graded challenges were performed when both tests were negative starting with 1/100th of the dose. Cephalosporin skin tests were positive in 72% of patients; 6.6% had negative skin tests but positive RAST. Of those with negative IgE testing, 8 accepted challenges and 2 were positive. In both of the aforementioned studies, RASTs were developed in each of the research laboratories and are not commercially available. Romano et al. also performed skin testing in 148 children with histories of cephalosporin allergy (43 with immediate and 105 with delayed reactions).(59) In those children with immediate reactions, 76.7% had positive skin tests, while none of the children with delayed reactions had positive delayed intradermal or patch tests. A study from Korea using cephalosporin skin testing (2 mg/ml) and oral challenge in 1421 healthy controls suggested a false positivity rate of 5.2%.(60) How commonly false positive skin tests occur in subjects with histories of cephalosporin allergy is unknown as few studies have performed challenges to patients with positive cephalosporin skin tests. Christiansen et al. evaluated patients with clinical histories suggestive of cefuroxime perioperative anaphylaxis and 7/7 with positive skin prick tests had positive challenges.(61) This suggests that for patients with anaphylaxis, skin testing has a very high positive predictive value.

The ideal concentration for cephalosporin skin testing is not entirely clear. Many studies have utilized testing at 2 mg/ml, however non-irritating concentrations to cephalosporins have been shown to range from 10–33 mg/ml.(62) The exception was cefepime which was shown to be irritating in concentrations of 20 mg/ml. Uyttebroek et al. evaluated patients with cefazolin perioperative anaphylaxis and identified an additional 27% of patients when using a concentration of 20 mg/ml compared to 2 mg/ml.(55) In the aforementioned study by Christiansen et al., they identified 8 patients (34.8%) who were positive on challenge only, however they utilized a low skin test concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Whether skin testing with a higher concentration (e.g. 2–20 mg/ml) would have identified these “false negatives” is unknown. Overall, we recommend using higher non-irritating skin test concentrations in evaluation of patients with histories of immediate reactions to cephalosporins, especially those with anaphylactic histories. Of note in the United States only sterile preparations of drugs are utilized for intradermal testing therefore there is no testing strategy available for aminocephalosporins such as cefadroxil, cephalexin, cefprozil and cefaclor, which are only available in oral formulations. Other studies outside of the United States have utilized 2 mg/ml and 20 mg/ml of the diluted oral formulation as a prick and intradermal testing strategy, however this technique is rarely used.(58)

Nonimmediate Reactions

Skin testing using both delayed intracutaneous as well as patch tests have been investigated in cases of nonimmediate cephalosporin reactions. Romano et al. evaluated 105 patients with histories of benign exanthema and found only 6 (5.7%) with positive delayed intradermal skin tests and 3 with positive patch tests (all of whom had positive intradermal tests).(63) Of those with negative tests, 86 were challenged and all were negative. One patient had an indeterminate skin test to cephalexin 2 mg/ml and a positive challenge and afterwards, tests for cephalexin, cefaclor, and cefatrizine were performed at 20 mg/ml. A Finnish study found positive patch tests in 12/290 (4.1%) with cutaneous reactions to cephalosporins.(64) Pinho et al. found positive patch tests in 4/91 (4.4%) of cutaneous reactions.(65) Positive patch tests have been rarely reported in cases of SCAR to cephalosporins.(65, 66) Given the low rate of positive skin tests, as well as the low rate of confirmed delayed reactions, the utility of delayed cephalosporin skin tests remains unclear.

In Vitro Testing For Cephalosporins

Current standardized serologic testing for cephalosporins is lacking. Having reliable serologic testing for these agents would be ideal for helping to validate cephalosporin skin testing results or for providing an alternative approach for diagnosing cephalosporin allergy when skin testing is not possible (i.e., in patients with dermotographism or taking medications that have anti-histamine receptor 1 activity) or not feasible (e.g., no allergist access or availability). Several studies have evaluated specific cephalosporin IgE assays that have been correlated with cephalosporin skin testing and challenge results that have been helpful for providing data on their potential positive and negative predictive value in the diagnosis of cephalosporin allergy. The immunoassay methods used to detect specific IgE have been radioimmunoassay (RIA), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and fluorescent enzyme immunoassay (FEIA).(48, 50, 54, 67, 68) The cephalosporin conjugates used for these assays have been synthesized essentially using the same methods used for synthesizing penicillin conjugates.(68) However, these assays have been limited to only a few cephalosporins used primarily for research due to their poor sensitivity compared to skin testing and lack of availability. (50) In fact, the only commercially available in vitro test is a FEIA IgE immunoassay for cefaclor (ImmunoCAP, Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden).

A study evaluating 102 patients with a history of cephalosporin allergy using skin testing and an in vitro cefaclor (an aminocephalosporin) immunoassay, found that 16 had a positive skin test whereas only 8/16 subjects had a positive in vitro sIgE test to cefaclor.(54) The results indicate that a patient reacting to a cephalosporin that shares a similar or identical side chain with penicillin, has a relative risk ratio of cross-reacting with at least one penicillin of 2.89 (95% CI, 1.37–6.11).(54) However, this study and others have demonstrated significant heterogeneity in cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins as well as between cephalosporin groups indicating the need for a broader array of cephalosporin reagents to adequately assess for cephalosporin sIgE using in vitro assays.(48, 54, 69)

Another assay that may be useful for assessing cephalosporin hypersensitivity is the basophil activation test (BAT), which measures surface CD63 or CD203c expressed on basophils after stimulation with the culprit drug. In general, its specificity is greater than the sensitivity (Sensitivity - 50–60 %; Specificity - > 90%) but there is limited information available using this assay for assessing cephalosporin allergy.(70) A study of 18 patients with cefazolin perioperative anaphylaxis confirmed by intradermal skin tests found that BAT using CD63 or CD203c was 38–75% sensitive respectively.(71)

Cephalosporin Challenge

As indicated above, the negative predictive value associated with immediate hypersensitivity skin testing to cephalosporins has not been established. For this reason, when skin testing does not reveal remarkable wheal/flare reaction to a cephalosporin drug, challenge with the culprit cephalosporin drug is recommended in order to definitively rule out cephalosporin allergy.(72) As has been observed for penicillin, in patients with histories of cephalosporin allergy clearly compatible with IgE-mediated pathogenesis, the likelihood of negative skin tests and cephalosporin tolerance increases the more time has elapsed since the adverse reaction occurred.(73) Thus, patients with negative skin tests and a history compatible with an IgE-mediated reaction, who have experienced an adverse reaction within the previous 6 months, may be regarded as being at elevated risk and considered as candidates for safeguards such as a graded-dose challenge beginning at a lower dose (e.g. 1/100th-1/10th of the full dose).

The positive predictive value of cephalosporin skin testing has also not been established; however, false positive skin tests to cephalosporin antibiotics may be encountered.(60) Limited retrospective data suggest that adverse reactions upon challenge will be observed in approximately one-third to one half of patients with positive skin tests to penicillin.(74) Similarly, as such reactions may be serious or even life-threatening, should a cephalosporin drug to which a positive skin test is observed be clearly indicated, without an equally efficacious alternative that can be used, desensitization should be performed.

Rapid Drug Desensitization

Due to frequent and repeated antibiotic exposures, there is a higher prevalence of cephalosporin allergy and anaphylaxis in targeted populations such as cystic fibrosis, immunodeficiencies and spina bifida patients. In these populations and in patients with severe reactions to cephalosporins, for which these antibiotics are considered first-line therapy, rapid drug desensitization should be considered as a therapeutic approach.(75) Patients with positive cephalosporin skin tests and/or anaphylactic histories are good candidates for rapid intravenous or oral cephalosporin desensitization.(76) Protocols for cephalosporin rapid drug desensitization include choosing a safe starting dose, typically 1/10,000th −1/1,000,000th of the target dose; doubling steps and allowing for a minimum of 15 minutes between steps.(77, 78) Volumes for desensitization should match the volumes for regular administration of cephalosporins.(79) Since cephalosporins are dosed daily, patients are only desensitized once and subsequent doses are managed as regular administration. Although CF patients are high-risk desensitization candidates due to severe respiratory symptoms and low FEV1, there is no formal contraindication for desensitization. In an earlier study, 52 desensitization procedures were done on 15 CF patients (FEV1=11–77 percent predicted).(79) Either a 12-step or 16-step desensitization protocol with cephalosporins including ceftazidime and cefepime was utilized (Table 1). All patients completed the desensitization; 96.2% had no severe adverse events, minor reactions occurred in 9.6% of patients.

Table 1.

Desensitization protocol for cefepime79

| Name of medication: Cefepime | ||||||

| Total mg per bag | Amount of bag infused (ml) | |||||

| Solution 1 | 20 ml of | 0.100 mg/ml | 2.00 | 1.87 | ||

| Solution 2 | 20 ml of | 1.000 mg/ml | 20.00 | 3.75 | ||

| Solution 3 | 20 ml of | 10.000 mg/ml | 200.30 | 7.50 | ||

| Solution 4 | 20 ml of | 96.053 mg/ml | 1921.30 | 20.00 | ||

| Step | Solution | Rate (mL/h) | Time (min) | Volume infused per step (mL) | Dose administered with this stem (mg) | Cumulative dose (mg) |

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 15 | 0.12 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.025 | 0.038 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 0.50 | 0.050 | 0.088 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 1.00 | 0.100 | 0.188 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.250 | 0.438 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 0.50 | 0.500 | 0.938 |

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.938 |

| 8 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 2.00 | 2.000 | 3.938 |

| 9 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 0.50 | 5.000 | 8.938 |

| 10 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 1.00 | 10.000 | 18.938 |

| 11 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 2.00 | 20.000 | 38.938 |

| 12 | 3 | 16 | 15 | 4.00 | 40.000 | 78.938 |

| 13 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 1.00 | 96.053 | 174.991 |

| 14 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 2.50 | 240.133 | 415.123 |

| 15 | 4 | 20 | 15 | 5.00 | 480.266 | 895.389 |

| 16 | 4 | 40 | 17.25 | 11.50 | 1104.611 | 2000.000 |

Total time = 242.25 min (4h 2 min)

Special Groups: Cystic Fibrosis and Immunocompromised Patients

Antibiotic hypersensitivity is a major complication in the treatment of patients with chronic conditions like cystic fibrosis (CF) and immunodeficiency. Patients with these conditions require frequent courses of antibiotics, which likely leads to sensitization and accounts for the high prevalence of antibiotic allergies. Patients with CF are three time more likely to have a beta-lactam allergy than the general population(80, 81) while rates of self-reported beta-lactam allergy range from 7–33% in common variable immunodeficiency patients.(82, 83) Ceftazidime has been reported to be the most common culprit antibiotic causing HSR in some studies of CF patients, however these same patients often tolerate inhaled aztreonam, which shares an R1 side chain with ceftazidime.(84)

Beta-lactam allergies in CF patients or other immunocompromised states have significant implications from a clinical perspective. They lead to the potential for inadequate treatment, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (and associated consequences) and potentially unnecessary drug desensitization. This is an important issue as the increase in life expectancy of patients with CF is due to a better management of infections with antibiotics.(85) Unfortunately, penicillin skin testing is underutilized in the CF population.(86)

The most common symptoms of beta-lactam allergy in patients with CF are pruritus and rash.(81) Koch et al. studied 121 patients with cystic fibrosis, 4.5% of the courses were associated with adverse reactions.(87) However, most of these reactions were nonimmediate, such as maculopapular rashes and drug fever. Piperacillin and ceftazidime accounted for most reactions. Wills et al. also reported that nonimmediate reactions were seen commonly (34% of all reactions) in 53 patients with CF.(80)

Skin testing and drug challenges, as described earlier, are well studied and protocols should be used for routine evaluation in patients with conditions like CF and CVID. In addition to immediate reactions discussed previously, rapid desensitizations have been utilized successfully for nonimmediate reactions to ceftazidime in CF patients.(88)

Future Challenges

While our knowledge of cephalosporin hypersensitivity and management is advancing, there are still several areas that need further research (Table 2). The lack of knowledge regarding cephalosporin antigenic determinants is a hindrance to the development of improved in vivo and in vitro diagnostic tests. Adequately powered studies to assess the diagnostic utility of skin and in vitro tests have not been performed, which limit the clinician’s interpretation of positive or negative skin tests. Novel methods such as the use of nanoallergen platforms, previously used in platin hypersensitivity, may provide mechanistic and diagnostic insights.(89) The epidemiology of beta-lactam hypersensitivity is poorly defined in large datasets in the U.S., and to date, allergy referral population epidemiology appears different in the U.S. compared to Europe where most cephalosporin hypersensitivity studies were conducted. Hence the generalizability of practices and approaches for cephalosporin hypersensitivity may not apply across different populations. Despite these knowledge gaps, a rational and risk-based approach to patients presenting with cephalosporin hypersensitivity exists today, but will be refined over time as more clinicians and researchers work to define optimal testing strategies for the growing population reporting a cephalosporin allergy.

Table 2:

Future Needs in Cephalosporin Hypersensitivity

| • Improved cephalosporin epidemiology studies with well-defined phenotypes and clinical risk factors |

| • Identification of relevant cephalosporin antigenic determinants |

| • U.S. studies with adequate power to evaluate genetic risk factors for cephalosporin allergy |

| • Precise determination of risk of administration of cephalosporins to patients with well-defined penicillin allergy histories |

| • Cross-reactivity patterns of cephalosporins in non-European populations |

| • Ideal concentration for immediate hypersensitivity cephalosporin skin tests |

| • Diagnostic test characteristics of immediate and delayed skin tests for cephalosporin allergy |

| • Accuracy of in vitro tests for cephalosporin allergy |

| • Development of novel diagnostic tests for cephalosporin allergy |

Acknowledgments

No funding was received for this study.

Abbreviations

- ADRs

Adverse drug reactions

- MDIS

Multiple drug intolerance syndrome

- MDAS

Multiple drug allergy syndrome

- HSR

hypersensitivity reaction

- EHR

electronic health record

- SCAR

severe cutaneous adverse reactions

- DRESS

drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- SJS/TEN

Stevens Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis

- NMBAs

neuromuscular blocking agents

- RAST

radioallergosorbent test

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FEIA

fluorescent enzyme immunoassay

- SSLR

serum sickness-like reaction

Footnotes

Drs. Khan, Banerji, Bernstein, Bilgicer, Castells, Ein, Lang, and Phillips have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Dr. Blumenthal reports a licensed clinical decision support tool that is used institutionally for inpatient beta-lactam allergy evaluations at Partners HealthCare System.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baggs J, Fridkin SK, Pollack LA, Srinivasan A, Jernigan JA. Estimating National Trends in Inpatient Antibiotic Use Among US Hospitals From 2006 to 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1639–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Versporten A, Coenen S, Adriaenssens N, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, et al. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient cephalosporin use in Europe (1997–2009). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 Suppl 6:vi25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, Goss F, Topaz M, Slight SP, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778 e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macy E, Contreras R. Adverse reactions associated with oral and parenteral use of cephalosporins: A retrospective population-based analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(3):745–52 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saff RR, Camargo CA Jr., Clark S, Rudders SA, Long AA, Banerji A. Utility of ICD-9-CM Codes for Identification of Allergic Drug Reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(1):114–9 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal KG, Wolfson AR, Li Y, Seguin CM, Phadke NA, Banerji A, et al. Allergic Reactions Captured by Voluntary Reporting. J Patient Saf. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Acker WW, Chang Y, Banerji A, Ghaznavi S, et al. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome and multiple drug allergy syndrome: Epidemiology and associations with anxiety and depression. Allergy. 2018;73(10):2012–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung IY, Kim JJ, Lee SJ, Kim J, Seong H, Jeong W, et al. Antibiotic-Related Adverse Drug Reactions at a Tertiary Care Hospital in South Korea. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4304973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumenthal KG, Kuhlen JL Jr., Weil AA, Varughese CA, Kubiak DW, Banerji A, et al. Adverse Drug Reactions Associated with Ceftaroline Use: A 2-Center Retrospective Cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):740–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigby M Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(6):765–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong A, Seger DL, Lai KH, Goss FR, Blumenthal KG, Zhou L. Drug Hypersensitivity Reactions Documented in Electronic Health Records within a Large Health System. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Lau JJ, Zhou L. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a cross-sectional analysis of patients in an integrated allergy repository of a large health care system. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(2):277–80 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, Topaz M, Bates DW, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug-Induced Anaphylaxis Documented in Electronic Health Records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurrieri C, Weingarten TN, Martin DP, Babovic N, Narr BJ, Sprung J, et al. Allergic reactions during anesthesia at a large United States referral center. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(5):1202–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Estrada A, Pien LC, Zell K, Wang XF, Lang DM. Antibiotics are an important identifiable cause of perioperative anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(1):101–5 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhlen JL Jr., Camargo CA Jr., Balekian DS, Blumenthal KG, Guyer A, Morris T, et al. Antibiotics Are the Most Commonly Identified Cause of Perioperative Hypersensitivity Reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfson AR, Zhou L, Li Y, Phadke NA, Chow OA, Blumenthal KG. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome Identified in the Electronic Health Record Allergy Module. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White KD, Chung WH, Hung SI, Mallal S, Phillips EJ. Evolving models of the immunopathogenesis of T cell-mediated drug allergy: The role of host, pathogens, and drug response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):219–34; quiz 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavlos R, White KD, Wanjalla C, Mallal SA, Phillips EJ. Severe Delayed Drug Reactions: Role of Genetics and Viral Infections. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37(4):785–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trubiano J, Stone C, Grayson M, Urbancic K, Slavin M, Thursky K, et al. The 3 Cs of Antibiotic Allergy-Classification, Cross-Reactivity, and Collaboration. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adkinson NF Jr., Mendelson LM, Ressler C, Keogh JC. Penicillin minor determinants: History and relevance for current diagnosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(5):537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine BB, Ovary Z. Studies on the mechanism of the formation of the penicillin antigen. III. The N-(D-alpha-benzylpenicilloyl) group as an antigenic determinant responsible for hypersensitivity to penicillin G. J Exp Med. 1961;114:875–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariza A, Mayorga C, Fernandez TD, Barbero N, Martin-Serrano A, Perez-Sala D, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactams: relevance of hapten-protein conjugates. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2015;25(1):12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Sancho F, Perez-Inestrosa E, Suau R, Montanez MI, Mayorga C, Torres MJ, et al. Synthesis, characterization and immunochemical evaluation of cephalosporin antigenic determinants. J Mol Recognit. 2003;16(3):148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Inestrosa E, Suau R, Montanez MI, Rodriguez R, Mayorga C, Torres MJ, et al. Cephalosporin chemical reactivity and its immunological implications. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5(4):323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karnes J, Miller M, White K, Konvinse K, Pavlos R, Redwood A, et al. Applications of Immunopharmacogenomics: Predicting, Preventing, and Understanding Immune-Mediated Adverse Drug Reactions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;59:463–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daly AK, Donaldson PT, Bhatnagar P, Shen Y, Pe’er I, Floratos A, et al. HLA-B*5701 genotype is a major determinant of drug-induced liver injury due to flucloxacillin. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):816–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicoletti P, Aithal GP, Chamberlain TC, Coulthard S, Alshabeeb M, Grove JI, et al. Drug-induced injury due to flucloxacillin: relevance of multiple HLA alleles. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucena MI, Molokhia M, Shen Y, Urban TJ, Aithal GP, Andrade RJ, et al. Susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced liver injury is influenced by multiple HLA class I and II alleles. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konvinse KC, Trubiano JA, Pavlos R, James I, Shaffer CM, Bejan CA, et al. HLA-A*32:01 is strongly associated with vancomycin-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng X, Earnshaw CJ, Tailor A, Jenkins RE, Waddington JC, Whitaker P, et al. Amoxicillin and Clavulanate Form Chemically and Immunologically Distinct Multiple Haptenic Structures in Patients. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29(10):1762–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia Y, Su T, Gu Y, Li C, Zhou X, Su J, et al. HLA-DQA1, -DQB1, and -DRB1 Alleles Associated with Acute Tubulointerstitial Nephritis in a Chinese Population: A Single-Center Cohort Study. J Immunol. 2018;201(2):423–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenthal KG, Youngster I, Shenoy ES, Banerji A, Nelson SB. Tolerability of cefazolin after immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions to nafcillin in the outpatient setting. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(6):3137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez CA, Smith C, Yang W, Mullighan CG, Qu C, Larsen E, et al. Genome-wide analysis links NFATC2 with asparaginase hypersensitivity. Blood. 2015;126(1):69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garon S, Pavlos R, White K, Brown N, Stone C Jr., Phillips E. Pharmacogenomics of off-target adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(9):1896–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oussalah A, Mayorga C, Blanca M, Barbaud A, Nakonechna A, Cernadas J, et al. Genetic variants associated with drugs-induced immediate hypersensitivity reactions: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review. Allergy. 2016;71(4):443–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gueant JL, Romano A, Cornejo-Garcia JA, Oussalah A, Chery C, Blanca-Lopez N, et al. HLA-DRA variants predict penicillin allergy in genome-wide fine-mapping genotyping. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King BA, Geelhoed GC. Adverse skin and joint reactions associated with oral antibiotics in children: the role of cefaclor in serum sickness-like reactions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39(9):677–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kearns GL, Wheeler JG, Childress SH, Letzig LG. Serum sickness-like reactions to cefaclor: role of hepatic metabolism and individual susceptibility. J Pediatr. 1994;125(5 Pt 1):805–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin YF, Yang CH, Sindy H, Lin JY, Rosaline Hui CY, Tsai YC, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions related to systemic antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(10):1377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong SW, Mertes PM, Petitpain N, Hasdenteufel F, Malinovsky JM, Gerap. Hypersensitivity reactions during anesthesia. Results from the ninth French survey (2005–2007). Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78(8):868–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antunes J, Kochuyt AM, Ceuppens JL. Perioperative allergic reactions: experience in a Flemish referral centre. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2014;42(4):348–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mertes PM, Volcheck GW, Garvey LH, Takazawa T, Platt PR, Guttormsen AB, et al. Epidemiology of perioperative anaphylaxis. Presse Med. 2016;45(9):758–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guyer AC, Saff RR, Conroy M, Blumenthal KG, Camargo CA Jr., Long AA, et al. Comprehensive allergy evaluation is useful in the subsequent care of patients with drug hypersensitivity reactions during anesthesia. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(1):94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sadleir PH, Clarke RC, Platt PR. Cefalotin as antimicrobial prophylaxis in patients with known intraoperative anaphylaxis to cefazolin. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(4):464–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Rumi G, Bousquet PJ. IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to cephalosporins: cross-reactivity and tolerability of penicillins, monobactams, and carbapenems. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(5):994–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park MA, Solensky R, Khan DA, Castells MC, Macy EM, Lang DM. Patients with positive skin test results to penicillin should not undergo penicillin or amoxicillin challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(3):816–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antunez C, Blanca-Lopez N, Torres MJ, Mayorga C, Perez-Inestrosa E, Montanez MI, et al. Immediate allergic reactions to cephalosporins: evaluation of cross-reactivity with a panel of penicillins and cephalosporins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Hsu JT, Wolfson AR, Berkowitz DN, Carballo VA, et al. Outcomes from an Inpatient Beta-Lactam Allergy Guideline Across a Large US Health System. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Trubiano JA, Stone CA, Grayson ML, Urbancic K, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, et al. The 3 Cs of Antibiotic Allergy-Classification, Cross-Reactivity, and Collaboration. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moss RB, McClelland E, Williams RR, Hilman BC, Rubio T, Adkinson NF. Evaluation of the immunologic cross-reactivity of aztreonam in patients with cystic fibrosis who are allergic to penicillin and/or cephalosporin antibiotics. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13 Suppl 7:S598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Maggioletti M, Zaffiro A, Caruso C, et al. IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to cephalosporins: Cross-reactivity and tolerability of alternative cephalosporins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(3):685–91 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uyttebroek AP, Decuyper II, Bridts CH, Romano A, Hagendorens MM, Ebo DG, et al. Cefazolin Hypersensitivity: Toward Optimized Diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(6):1232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pipet A, Veyrac G, Wessel F, Jolliet P, Magnan A, Demoly P, et al. A statement on cefazolin immediate hypersensitivity: data from a large database, and focus on the cross-reactivities. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(11):1602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang MS, Kang DY, Seo B, Park HJ, Park SY, Kim MY, et al. Incidence of cephalosporin-induced anaphylaxis and clinical efficacy of screening intradermal tests with cephalosporins: A large multicenter retrospective cohort study. Allergy. 2018;73(9):1833–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romano A, Gueant-Rodriguez RM, Viola M, Amoghly F, Gaeta F, Nicolas JP, et al. Diagnosing immediate reactions to cephalosporins. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(9):1234–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Alonzi C, Viola M, Bousquet PJ. Diagnosing hypersensitivity reactions to cephalosporins in children. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):521–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoon SY, Park SY, Kim S, Lee T, Lee YS, Kwon HS, et al. Validation of the cephalosporin intradermal skin test for predicting immediate hypersensitivity: a prospective study with drug challenge. Allergy. 2013;68(7):938–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christiansen IS, Kroigaard M, Mosbech H, Skov PS, Poulsen LK, Garvey LH. Clinical and diagnostic features of perioperative hypersensitivity to cefuroxime. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(4):807–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Empedrad R, Darter AL, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Nonirritating intradermal skin test concentrations for commonly prescribed antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(3):629–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Alonzi C, Viola M, et al. Diagnosing nonimmediate reactions to cephalosporins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):1166–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lammintausta K, Kortekangas-Savolainen O. The usefulness of skin tests to prove drug hypersensitivity. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(5):968–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinho A, Coutinho I, Gameiro A, Gouveia M, Goncalo M. Patch testing - a valuable tool for investigating non-immediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions to antibiotics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barbaud A, Collet E, Milpied B, Assier H, Staumont D, Avenel-Audran M, et al. A multicentre study to determine the value and safety of drug patch tests for the three main classes of severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blanca M, Fernandez J, Miranda A, Terrados S, Torres MJ, Vega JM, et al. Cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins: clinical and immunologic studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83(2 Pt 1):381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blanca M, Mayorga C, Perez E, Suau R, Juarez C, Vega JM, et al. Determination of IgE antibodies to the benzyl penicilloyl determinant. A comparison between poly-L-lysine and human serum albumin as carriers. J Immunol Methods. 1992;153(1–2):99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dickson SD, Salazar KC. Diagnosis and management of immediate hypersensitivity reactions to cephalosporins. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45(1):131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greiwe JaBJ. In Vitro and In Vivo Tests for Drug Hypersensitivity Reactions. first ed: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Uyttebroek AP, Sabato V, Cop N, Decuyper II, Faber MA, Bridts CH, et al. Diagnosing cefazolin hypersensitivity: Lessons from dual-labeling flow cytometry. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(6):1243–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Zaffiro A, Caruso C, Quaratino D. Natural evolution of skin-test sensitivity in patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to cephalosporins. Allergy. 2014;69(6):806–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Macy E, Burchette RJ. Oral antibiotic adverse reactions after penicillin skin testing: multi-year follow-up. Allergy. 2002;57(12):1151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giavina-Bianchi P, Aun MV, Galvão VR, Castells M. Rapid Desensitization in Immediate Hypersensitivity Reaction to Drugs. Current Treatment Options in Allergy. 2015;2(3):268–85. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Macy E, Romano A, Khan D. Practical Management of Antibiotic Hypersensitivity in 2017. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):577–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cernadas JR, Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, Torres MJ, Bircher A, et al. General considerations on rapid desensitization for drug hypersensitivity - a consensus statement. Allergy. 2010;65(11):1357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Win PH, Brown H, Zankar A, Ballas ZK, Hussain I. Rapid intravenous cephalosporin desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(1):225–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Legere HJ 3rd, Palis RI, Rodriguez Bouza T, Uluer AZ, Castells MC. A safe protocol for rapid desensitization in patients with cystic fibrosis and antibiotic hypersensitivity. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8(6):418–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wills R, Henry RL, Antibiotic JLF hypersensitivity reactions in cystic fibrosis. Padiatr Child Health. 1998;34(4):325–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burrows JA, Nissen LM, Kirkpatrick CM, Bell SC. Beta-lactam allergy in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6(4):297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bjelac JA, Blanch MB, Fernandez J. Allergic disease in patients with common variable immunodeficiency at a tertiary care referral center. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):90–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hartman H, Schneider K, Hintermeyer M, Bausch-Jurken M, Fuleihan R, Sullivan KE, et al. Lack of Clinical Hypersensitivity to Penicillin Antibiotics in Common Variable Immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2017;37(1):22–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Whitaker P, Naisbitt D, Peckham D. Nonimmediate beta-lactam reactions in patients with cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(4):369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Plummer A, Wildman M, Gleeson T. Duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD006682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shah S, Shah S, Lehman E, Vender RL, Graff G, Ishmael FT. Characterization of Single and Multiple Antibiotic Allergies in Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koch C, Hjelt K, Pedersen SS, Jensen ET, Jensen T, Lanng S, et al. Retrospective clinical study of hypersensitivity reactions to aztreonam and six other beta-lactam antibiotics in cystic fibrosis patients receiving multiple treatment courses. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13 Suppl 7:S608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whitaker P, Shaw N, Gooi J, Etherington C, Conway S, Peckham D. Rapid desensitization for non-immediate reactions in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10(4):282–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deak PE, Kim B, Adnan A, Labella M, De Las Vecillas L, Castells M, et al. Nanoallergen platform for detection of platin drug allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, Molina J, Workman C, Tomazic J, et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(6):568–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang F, Liu H, Irwanto A, Fu X, Li Y, Yu G, et al. HLA-B*13:01 and the dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1620–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]