Significance

Brown planthopper (BPH) is the most destructive pest of rice and causes losses of billions of dollars annually. Genetic improvement of BPH resistance in rice remains a major challenge because of the limited number of resistance genes that have been identified, and because the molecular mechanisms underlying the resistance are still poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that BPH feeding induces the expression of an R2R3 MYB transcription factor, which in turn upregulates the expression of OsPALs genes, leading to increased biosynthesis and accumulation of salicylic acid and lignin. As a result, the plants gained increased resistance to BPH. Our results shed insights into the molecular mechanisms mediating BPH resistance and provide valuable targets for genetic improvement of BPH resistance in rice.

Keywords: rice, brown planthopper, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, salicylic acid, lignin

Abstract

Brown planthopper (BPH) is one of the most destructive insects affecting rice (Oryza sativa L.) production. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) is a key enzyme involved in plant defense against pathogens, but the role of PAL in insect resistance is still poorly understood. Here we show that expression of the majority of PALs in rice is significantly induced by BPH feeding. Knockdown of OsPALs significantly reduces BPH resistance, whereas overexpression of OsPAL8 in a susceptible rice cultivar significantly enhances its BPH resistance. We found that OsPALs mediate resistance to BPH by regulating the biosynthesis and accumulation of salicylic acid and lignin. Furthermore, we show that expression of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 in response to BPH attack is directly up-regulated by OsMYB30, an R2R3 MYB transcription factor. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the phenylpropanoid pathway plays an important role in BPH resistance response, and provide valuable targets for genetic improvement of BPH resistance in rice.

The brown planthopper (BPH) (Nilaparvata lugens Stål, Hemiptera, Delphacidae) is one of the most destructive insect pests of rice (Oryza sativa L.) throughout the rice-growing countries. It sucks the sap from the rice phloem, using its stylet, which causes direct damage to rice plants. In addition, it also transmits 2 viral diseases; namely, rice grassy stunt and rugged stunt (1, 2). Pesticides, which are costly and harmful to the environment, are still the most common strategy for combating BPH. Breeding resistant rice cultivars is believed to be the most cost-effective and environmentally friendly strategy for controlling BPH.

To date, at least 29 BPH resistance genes have been mapped on rice chromosomes, but only 6 have been successfully cloned, including Bph14, Bph9 (allelic to Bph1, Bph2, Bph7, Bph10, Bph21, Bph18, and Bph26), Bph3, Bph6, Bph29, and Bph32. Both Bph14 and Bph9 encode nucleotide-binding and leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins (3, 4), whereas Bph3 contains a cluster of 3 genes predicted to encode lectin receptor kinases (OsLecRK1-OsLecRK3) (5). Bph6 encodes an exocyst-localized protein (6). Bph29 encodes a B3 DNA-binding domain-containing protein (7). Bph32 encodes an unknown SCR domain-containing protein (8). Despite the progress, the action mechanisms of these BPH resistance genes are still not well understood.

Previous studies have shown that lignin, salicylic acid (SA), and other polyphenolic compounds derived from the phenylpropanoid pathway play important roles in plant defense against various plant pathogens and insect pests (9–11). Lignin, as one of the main components of the plant cell wall, plays an important role in determining plant cell wall mechanical strength, rigidity, and hydrophobic properties. When plants are infected with pathogens, increased accumulation of lignin in the cell wall provides a basic barrier against pathogen spread (12). In addition, it is reported that expression of lignin biosynthesis genes and lignin accumulation are induced by aphid penetration, which limits the invasion of aphids (13). Previous studies have also found that expression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), which encodes the first committed enzyme in phenylpropanoid pathway, is induced by sap-sucking herbivores; for example, aphid and BPH (14–16). However, it is not clear whether lignin deposition and altered expression of PAL and SA content play direct roles in BPH resistance in rice.

In this study, we demonstrate that the phenylpropanoid pathway plays an important role in BPH resistance. The expression of 8 OsPALs is significantly induced by BPH feeding. Knockdown or overexpression of OsPALs can significantly affect the level of lignin and SA, leading to reduced or enhanced BPH resistance, respectively. In addition, the expression of OsPALs in response to BPH attack is directly regulated by OsMYB30, an R2R3 MYB-type transcription factor.

Results

Genes Relevant to the Phenylpropanoid and Diterpenoid Phytoalexins Pathway Are Up-Regulated by BPH Feeding.

To explore the molecular basis underlying BPH resistance in rice, we performed a microarray analysis of genes that were differentially expressed in a BPH-resistant cultivar, Rathu Heenati (RH), and a susceptible cultivar, 02428. Compared with 02428, a total of 2,422 genes were significantly up-regulated in RH after infestation with BPH. Gene ontology enrichment analysis showed that genes related to multiple metabolic pathways were enriched in the resistant plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B).

To eliminate the interference caused by the different genetic backgrounds of the 2 varieties, we conducted a cDNA microarray assay with 2 pools of plants consisting of 10 highly resistant or susceptible plants, respectively, from the RH/02428 F2:3 population (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). A total of 348 genes were found that were highly expressed in the resistant pool infested with BPH (RB) in comparison with the resistant pool not infested with BPH (RN), and 227 genes were significantly up-regulated in the resistant pool infested with BPH (RB) in comparison with the susceptible pool infested with BPH (SB). Three-way comparison analysis (RH vs. 02428, RB vs. RN, and RB vs. SB) identified 29 genes that were present in all these comparisons (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D), including 4 genes annotated as PAL and 4 genes related to diterpenoid phytoalexins biosynthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). Up-regulation of these genes in the resistant plants was also confirmed by quantitative reverse transcriptase (qRT)-PCR analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). These results indicate that the PAL-mediated phenylpropanoid and diterpenoid phytoalexins pathway may play important roles in the defense response to BPH.

Nine OsPAL genes were predicted in the Nipponbare reference genome database (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We therefore used qRT-PCR to analyze the expression patterns of these 9 OsPAL genes in response to BPH infestation in RH and 02428. Seven of the 9 OsPALs were induced by BPH feeding in RH, especially OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 (P < 0.01; SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Expression of OsPAL9 was not detected, probably due to the absence of OsPAL9 in the majority of indica rice (17). These results suggest that OsPALs might be involved in rice–BPH interactions.

Altered Expression of PALs Significantly affects BPH Resistance.

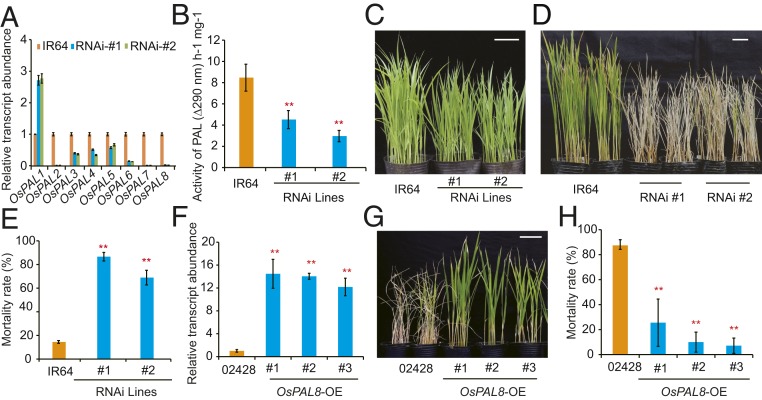

To verify the role of OsPALs in BPH resistance, we constructed an RNAi vector targeting the identical motif of the 9 PALs and used it to transform the BPH-resistant cultivar RH. Unfortunately, we failed to obtain any viable transgenic plants. We therefore transformed the RNAi vector into another BPH-resistant cultivar, IR64 (18), and obtained 5 independent RNAi T2 homozygous transgenic lines. Both the OsPAL transcript levels and enzyme activities were significantly reduced in the RNAi plants compared with the nontransgenic parent IR64 (Fig. 1 A and B). Compared with the parent IR64, the OsPAL RNAi plants were stunted (Fig. 1C) and more susceptible to BPH (Fig. 1 D and E). These results suggest that OsPALs are involved in regulation of BPH resistance.

Fig. 1.

Altered expression of PALs significantly impacts BPH resistance. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of OsPAL expression in the RNAi knockdown transgenic lines. The expression values are presented relative to those in the background parent IR64. (B) The activity of OsPALs in IR64 and OsPAL knockdown lines. (C) Seedlings of IR64 and OsPAL knockdown plants not infested with BPH. (Scale bar, 10 cm.) (D) Representative image of IR64 and OsPAL knockdown plants 7 d after infestation (dpi) with BPH. (Scale bar, 10 cm.) (E) Seedling mortality rate of IR64 and OsPAL knockdown lines infested with BPH. Data were collected at 7 dpi. (F) qRT-PCR analysis of OsPAL8 expression in the transgenic lines overexpressing OsPAL8. Expression level of OsPAL8 in the background parent 02428 was set as 1. (G) Representative image of 02428 and plants overexpressing OsPAL8 infested with BPH at 7 dpi. (Scale bar, 10 cm.) (H) Seedling mortality rate of 02428 and plants overexpressing OsPAL8 infested with BPH. Data were collected 7 dpi. Values are means ± SD of 3 biological replicates, by Student’s t test (B, E, F, and H, **P < 0.01).

BPH prefers to probe and suck sap from the rice stems and leaf sheaths (19). Among the 8 expressed OsPALs, OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 were specifically expressed in the stems and leaf sheaths (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Therefore, we overexpressed OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 in the susceptible variety 02428 to further confirm the role of these 2 OsPALs in BPH resistance. The transgenic lines overexpressing OsPAL8 displayed higher resistance to BPH compared with the parental 02428 plants (Fig. 1 F–H). Unexpectedly, the transgenic lines overexpressing OsPAL6 showed more susceptibility to BPH than the parental 02428 plants. Moreover, the height of transgenic plants overexpressing OsPAL6 was also significantly reduced compared with 02428 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). qRT-PCR analysis showed that the reduction of BPH resistance and plant height could be caused by cosuppression of OsPAL6 in the transgenic plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Together with the results of RNAi analyses, these observations support the notion that OsPALs positively regulate BPH resistance.

Influence of Altering OsPAL Expression on Lignin and SA.

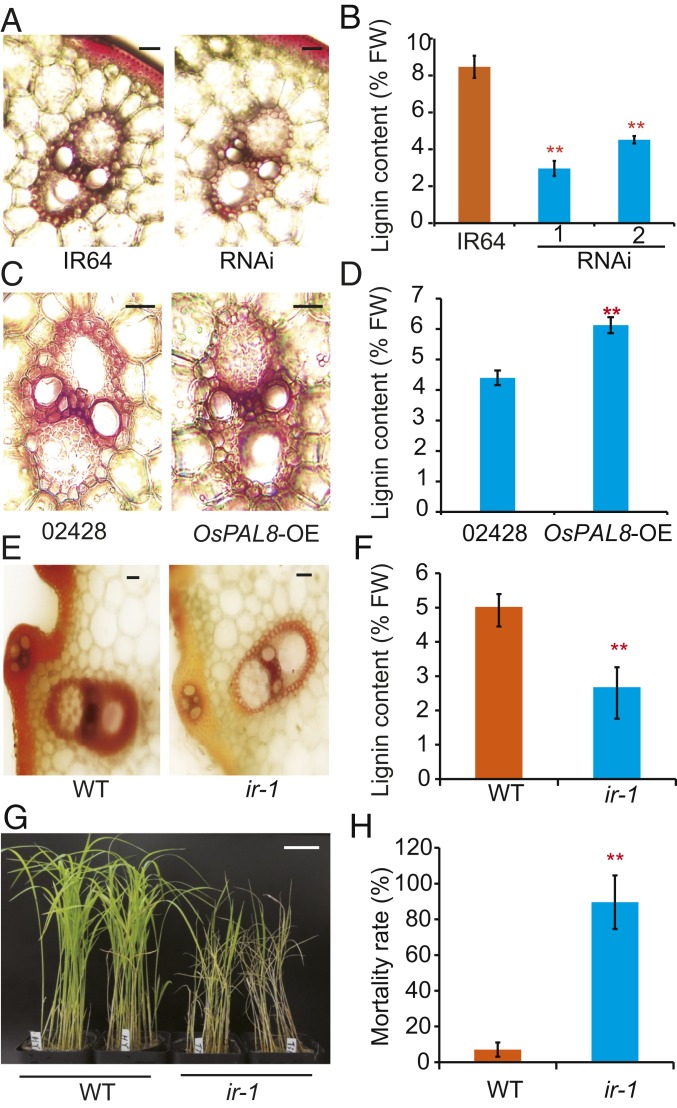

Previous studies have shown that PAL is involved in the biosynthesis of polyphenolic compounds, including lignin and SA in plants (20). To analyze lignin accumulation in the OsPAL RNAi and transgenic overexpression plants, we first examined lignin accumulation in fresh leaf sheaths by staining with phloroglucinol. Compared with the wild-type, the staining intensity was significantly reduced in the OsPAL RNAi plants (Fig. 2A), but increased in the plants overexpressing OsPAL8 (Fig. 2C). Next, we measured the lignin contents using the acetyl bromide method (21). Consistent with the histochemical staining results, lignin content was significantly reduced in the RNAi plants compared with the wild-type (Fig. 2B), but increased in the plants overexpressing OsPAL8 (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Lignin accumulation is associated with BPH resistance in rice. (A) Histochemical staining showing lignin accumulation in fresh leaf sheaths of IR64 and the OsPAL knockdown plants. (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (B) Lignin contents of IR64 and the OsPAL knockdown plants measured using the acetyl bromide method. (C) Histochemical staining showing lignin accumulation in fresh leaf sheaths of WT (02428) and the transgenic plants overexpressing OsPAL8. (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (D) Quantification of lignin content in fresh leaf sheaths of WT and plants overexpressing OsPAL8. (E) Histochemical staining showing lignin accumulation in fresh leaf sheaths of wild-type (WT) and lr-1 plants. (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (F) Quantification of lignin content in fresh leaf sheaths of WT and lr-1 plants. (G) Representative image of WT and lr-1 plants infested with BPH. (Scale bar, 10 cm.) (H) Seedling mortality rates of WT and lr-1 plants infested with BPH at 7 dpi. Values are means ± SD of 3 biological replicates (B, D, F, and H). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 in comparison with background parent or WT plant (Student’s t test).

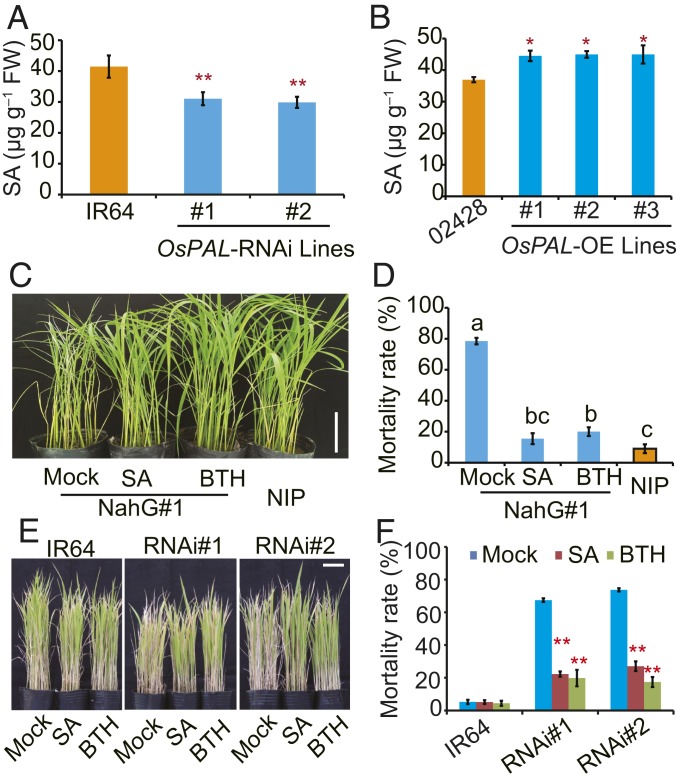

To determine the effect of OsPALs on SA levels, we compared free SA contents in the OsPAL RNAi and transgenic overexpression plants with the wild-type before and after infection with BPH. Regardless of BPH infestation, free SA levels were significantly decreased in the OsPAL RNAi plants (Fig. 3A), but increased in the plants overexpressing OsPAL8 (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that OsPALs participate in the biosynthesis of lignin and SA in rice.

Fig. 3.

OsPAL-mediated BPH resistance is associated with SA levels. SA level in the OsPAL knockdown lines (A) or plants overexpressing OsPAL8 (B). Error bars, mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 in comparison with background parent (Student’s t-test). Representative image (C) and seedling mortality rate (D) of NahG#1 transgenic plants infested with BPH for 5 d after pretreatment with SA, BTH, Mock, and the background parent Nipponbare (NIP), respectively. (Scale bar, 10 cm.) Error bars, mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates. Different letters on the histograms indicate statistically significant differences at P < 0.05 estimated by one-way ANOVA. (E) Representative image and (F) mortality rates of the OsPAL knockdown lines infested with BPH for 7 d after pretreatment with SA, BTH, and Mock, respectively. (Scale bar, 10 cm.) Error bars, mean ± SD of at least 3 biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 in comparison with IR64 (Student’s t-test).

Lignin and SA Significantly Affect the BPH Resistance.

To further investigate the causal relationship between lignin or SA levels and BPH resistance, we identified a rice mutant, lr-1, in which lignin content was reduced by ∼40% compared with the wild-type (Fig. 2 E and F). Notably, lr-1 was significantly more susceptible to BPH compared with the wild-type (Fig. 2 G and H). This result supports a positive role of lignin accumulation in conferring BPH resistance.

To verify the role of SA in BPH resistance response, we examined BPH resistance of the NahG#1 transgenic lines (which expresses the bacterial salicylate hydroxylase gene) (22). They showed that NahG#1 was more susceptible to BPH than the background parent (Fig. 3 C and D). In addition, we identified 5 rice mutants with reduced free SA contents by screening a mutant library composed of 256 accessions of rice transcription factor T-DNA mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A) and evaluated their BPH resistance. Similar to the plants expressing NahG, the BPH resistance levels of all 5 mutants with reduced SA were significantly decreased compared with the background control (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Moreover, exogenous application of SA on either NahG#1 or the OsPAL RNAi lines could significantly increase the BPH resistance (Fig. 3 C–F). Taken together, these results support an important role of SA in BPH resistance in rice.

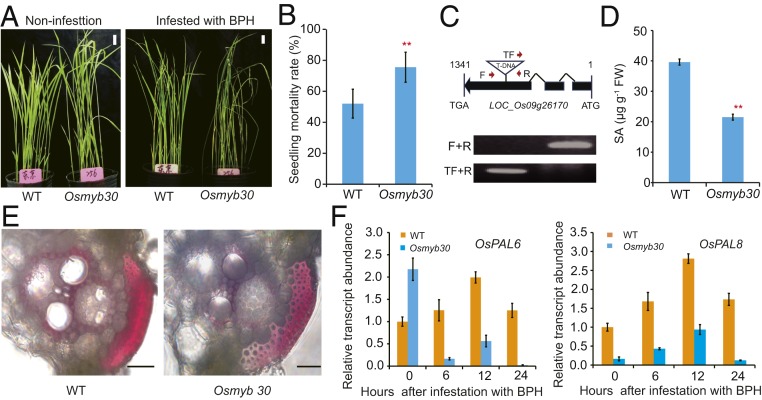

OsMYB30 Regulates the Expression of OsPALs to Confer BPH Resistance.

Previous studies have shown that tissue-specific expression of PAL is regulated by R2R3 MYB transcription factors in a few plant species through binding to the AC-rich elements (AC-I, ACCTACC; AC-II, ACCAACC; and AC-III, ACCTAAC) (20). Interestingly, we found that 1 of the mutants with reduced free SA content and BPH resistance (SA-R#256) is caused by T-DNA insertion in the first exon of OsMYB30, an R2R3 MYB transcription factor (Fig. 4 A–D). Compared with the wild-type Dongjin, the Osmyb30 mutant plant had slightly larger grains, but its thousand-grain weight was slightly reduced, possibly due to impaired grain filling. No significant differences were detected between the wild-type and mutant plants for other agronomic traits (plant height and heading date, etc.; SI Appendix, Fig. S7). qRT-PCR analysis showed that the level of OsMYB30 transcript was significantly induced by BPH infestation in wild-type plants at 3 and 6 h after BPH infestation, and that this induction was not observed in the Osmyb30 mutant plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). The content of lignin was also significantly decreased in the mutant line (Fig. 4E). Moreover, BPH-induced expression of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 was abolished in the mutant line (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that OsMYB30 likely regulates the expression of OsPALs in response to BPH infestation.

Fig. 4.

OsPALs-mediated BPH resistance is regulated by OsMYB30. (A) Representative image of Osmyb30 mutants infested with BPH for 5 d. (Scale bars, 1 cm.) (B) Seedling mortality rates of WT and Osmyb30 mutants infested with BPH. Data were collected at 7 dpi. (C) Verification of the T-DNA insertion in the Osmyb30 mutant. The positions of the F, R, and TF primers are indicated as red arrows. (D) SA levels in WT and the Osmyb30 mutant plants. (E) Histochemical staining showing lignin accumulation in fresh leaf sheaths of WT and the Osmyb30 mutant plants. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (F) qRT-PCR analysis of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 expression in the Osmyb30 mutant. The expression values are presented relative to those in WT without BPH infestation. Error bars, mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates, by Student’s t-test (B and D, **P < 0.01).

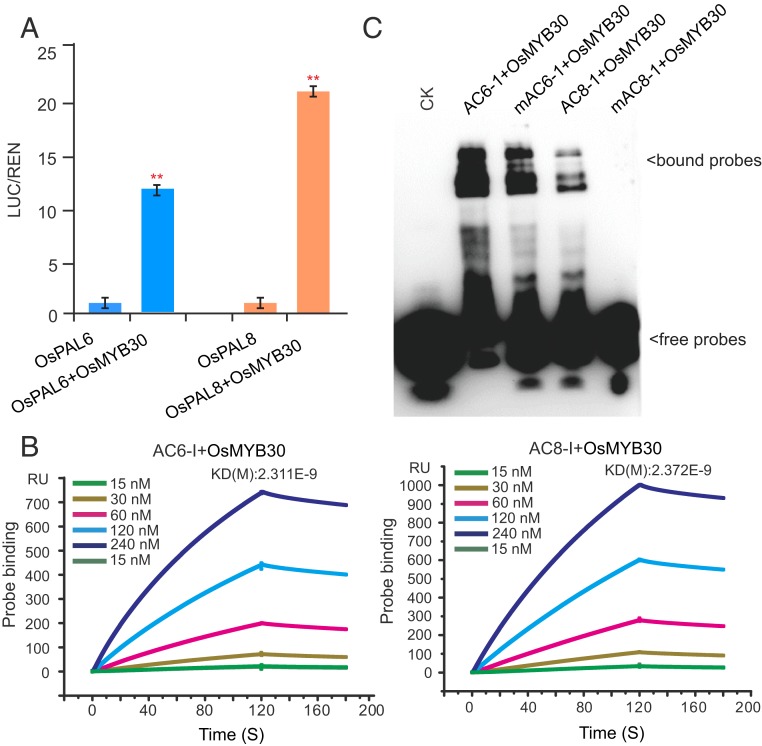

Next, we performed a transient expression assay to test whether OsMYB30 regulated the expression of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 using the dual-luciferase reporter system. LUC driven by the OsPAL6 or OsPAL8 promoters and REN driven by the CaMV35S promoter as an internal control were constructed in the same plasmids, together with an effector plasmid expressing OsMYB30 and expressed in the protoplasts of rice seedlings. We found that coexpression of OsMYB30 (but not the empty vector control) with LUC driven by the OsPAL6 or OsPAL8 promoters significantly increased the LUC/REN ratio (Fig. 5A), indicating that OsMYB30 up-regulates the expression of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8.

Fig. 5.

OsMYB30 binds to the AC-like elements in the promoters of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8. (A) Coexpression of OsMYB30 with LUC driven by the OsPAL6 or OsPAL8 promoters in rice leaf protoplasts. Error bars, mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates. **P < 0.01 by Student’s t-test. (B) Evaluation of the binding of OsMYB30 to the AC6-I and AC8-I elements in the promoter of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8, using the Biacore T200 instrument. Error bars, mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates. (C) EMSA assay showing the binding of OsMYB30 to the AC6-I and AC8-I elements in the promoters of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8. Error bars, mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates.

It was previously shown that R2R3 MYB transcription factors can directly bind to the AC element in the promoter region of PALs (20). Analysis of the 2-kb upstream regions of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 identified no typical AC element, but 3 AC-like elements in the upstream regions of both OsPAL6 (AC6-I, AC6-II, and AC6-III) and OsPAL8 (AC8-I, AC8-II, and AC8-III; SI Appendix, Fig. S9). To determine whether OsMYB30 has the ability to bind these motifs, Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments were performed using a Biacore T200 instrument. The results showed that immobilized OsMYB30 could tightly bind the AC6-I and AC8-I motifs in the promoters of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8, respectively (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the binding was confirmed by EMSA (Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay; Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Collectively, these results indicate that OsMYB30 directly up-regulates the expression of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 in response to BPH attack.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that PAL is a key enzyme in the phenylpropanoid pathway that is involved in the response to a variety of environmental stimuli, including pathogen infection, wounding, UV irradiation, and other stress conditions (20). BPH infestation has been observed to induce the expression of PAL genes (3); however, the role of PAL in the BPH resistance response remains unresolved. In this study, we established several lines of evidence supporting the notion that the PAL pathway plays an important role in the BPH resistance response and provided direct and unequivocal evidence that PAL mediated the BPH resistance response by regulating the production of lignin and SA. Moreover, we identified an R2R3 MYB transcription factor, OsMYB30, which can directly regulate the expression of OsPALs in response to BPH infestation (SI Appendix, Fig. S11).

In addition to participating in the biosynthesis of SA and lignin, PAL is also a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of phenolic phytoalexins in plants including flavonoids, anthocyanins, phytoalexins, and tannins. Previous studies have shown that phenolic phytoalexins affect the feeding behavior, development, and growth of insects (23, 24). In addition to phenylpropanoid pathway-related genes, it should be noted that we also observed up-regulation of genes involved in the biosynthesis of diterpenoid phytoalexins on BPH infestation in rice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Therefore, a possible role of other metabolites derived from the phenylpropanoid and diterpenoid phytoalexins pathway in BPH resistance cannot be ruled out at this stage.

This study also provides insights into the SA biosynthesis pathway in rice. It is generally believed that SA is made via either the chorismate or the PAL pathways in plants. In the chorismate pathway, isochorismate synthase converts chorismate into isochorismate (25). In bacteria, the conversion of isochorismate to SA is catalyzed by the isochorismate pyruvate lyase (26). Although isochorismate pyruvate lyase has not yet been reported in plants, the ics1 mutant accumulated roughly 10% and the ics1/ics2 double-mutant accumulated about 4% of the SA accumulated by wild-type Arabidopsis (27). These studies demonstrated that the chorismate pathway was the main route of SA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. However, the way SA is made in rice and other plants is still not clear. Several studies suggested that PAL is important for pathogen-induced SA formation in plants. Ogawa et al. (28) showed that SA is synthesized predominantly via the phenylalanine pathway in tobacco. In addition, earlier studies showed that tobacco mosaic virus-induced systemic acquired resistance is blocked in PAL-silenced tobacco plants (29), and that the pal1 pal2 pal3 pal4 quadruple knockout mutant of Arabidopsis maintains only about 25% and 50% of wild-type levels of basal- and pathogen-induced SA, respectively (30). Moreover, the PAL inhibitor 2-aminoindan-2-phosphonic acid could significantly reduce the induction of SA accumulation by pathogens in potato, cucumber, and Arabidopsis (10). Furthermore, it was shown that the SA induced by water deficit could be derived from the PAL pathway (31, 32). In the present study, we showed that the level of SA is significantly reduced in the OsPAL RNAi or OsPAL6 cosuppressed plants, but increased in the plants overexpressing OsPAL8 (Fig. 3 A and B). Together with the previous report (30), our results provide additional support for the notion that the PAL pathway is an important route of SA biosynthesis in rice.

Our finding that OsMYB30 can directly bind to the promoters of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 and regulate their expression in response to BPH is consistent with the earlier report that R2R3 MYB transcription factors can transactivate PAL promoters to control tissue-specific expression of PALs in other plants (20). Although no typical AC-rich elements were found in the promoters of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8, we found that OsMYB30 could directly bind to 2 nontypical AC-rich elements (AC6-I and AC8-I) in the promoters of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 and up-regulate their expression in response to BPH infestation. Moreover, the BPH-induced expression of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 was significantly impaired in the Osmyb30 mutant. Together, our results demonstrated an important role of R2R3 MYB transcription factors in regulating PAL gene expression and BPH resistance in rice. It will be interesting to test whether overexpression or induced expression of OsMYB30 can confer constitutive or enhanced BPH resistance in rice in future studies.

Methods

Plant Materials.

Rathu Heenati (RH), IR64, and Taichung Native 1 (TN1) were obtained from the International Rice Research Institute (Los Banos, the Philippines). 02428 was obtained from the Institute of Food Crops, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Dongjin and T-DNA mutants were kindly provided by Gynheung An (Department of Plant Systems Biotech, Kyung Hee University, Korea). Two rice pools were used for cDNA microarray assays, consisting of 10 highly resistant or susceptible plants from an F2 population derived from a cross between the BPH-resistant rice cultivar RH and the susceptible cultivar 02428. BPH-resistant rice cultivar IR64 and susceptible cultivar 02428 were used for PAL RNAi and overexpressing studies, respectively. Rice plants were grown in the Pailou experimental station at Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China (N 32°01′33.04″, E 118°50′7.20″).

BPH Maintenance.

A colony of the BPH was collected from rice fields in Tuqiao Town, Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province (N 31°55′51″, E 119°11′41″), and maintained on the susceptible cultivar TN1 at 22 °C, 75% RH and 16:8 L:D photoperiod in an artificial climate room at Nanjing Agricultural University.

BPH Resistance Evaluation.

BPH resistance evaluation was carried out in an artificial climate room with 22 °C, 75% RH, and 16:8 L:D photoperiod at Nanjing Agricultural University. BPH resistance was scored according to the standard evaluation systems of IRRI (33). A seedling bulk test was conducted to phenotype plant reaction to BPH feeding. To ensure all seedlings were at the same growth stage for BPH infestation, seeds were pregerminated in Petri dishes. About 30 seeds from a single plant were sown in a 10-cm-diameter plastic pot with a hole at the bottom. Seven days after sowing, seedlings were thinned to 25 plants per pot. At the second-leaf stage, the seedlings were infested with second to third instar BPH nymphs at 10 insects per seedling. For the RNAi plants, the seedling mortality was recorded when all the TN1 plants were dead. For the plants overexpressing OsPAL8, the seedling mortality was recorded when the seedling mortality rate of the background parent 02428 exceeded 80%. For the mutants with reduced SA and lignin content, the seedling mortality was recorded when the seedling mortality rate of the most susceptible plants exceeded 80%. There were 3 replicates for each cultivar or line.

RNA Extraction and Microarray Procedure.

Total RNA was extracted from 2-wk-old rice seedlings, using the TRIzol RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and purified using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit. The RNA concentration and integrity were determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA). The A260/A280 of RNA samples with ∼2.0 were used for gene expression analysis. RNAs from 3 biologic replicates for each line or pool of seedlings were separately used for reverse transcription and microarray analysis.

The total RNAs were used in target synthesis for the Rice Genome Array from Affymetrix. For cDNA microarray analysis, the mRNA samples were reverse transcribed in the presence of Cy3-dUTP (02428, SB, RN) or Cy5-dUTP (RH and RB). cDNA synthesis and cRNA preparation were performed according to the standard protocols (Affymetrix). Hybridization, washing, and staining were conducted in an Affymetrix GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640 and Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450. Data collection and analysis were performed using a Gene array Scanner 3000 7G and GeneChip Operating Software (Affymetrix). The entire microarray analysis was performed by Shanghai Biochip Co., Ltd.

For the microarray data, genes with log2 ratio of Cy3/Cy5 ≥1 or ≤−1 between different arrays and that had a P value of < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. The enriched gene ontology terms and their hierarchical relationships in biological process, cellular component, or molecular function were performed using the GOEAST program (http://omicslab.genetics.ac.cn/GOEAST/index.php).

Plasmid Construction.

To generate the overexpression constructs, the entire Coding sequence regions of OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 were amplified using gene-specific primers (SI Appendix, Table S1) from IR64 seedling cDNA, and the PCR products were inserted into the binary vector pCAMBIA1390 to produce pCAMBIA1390-OsPAL6 and pCAMBIA1305-OsPAL8, respectively. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

To generate the RNAi construct, 2 copies of a 220-bp cDNA fragment conserved in all 8 OsPALs were amplified by PCR, using primers RNAi1 and RNAi2 (SI Appendix, Table S2), and inserted as inverted repeats into the PA7 vector to generate a hairpin RNAi construct, which was then cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1305 with Hind III and EcoR I.

To construct the plasmids for recombinant protein expression, the entire Coding sequence of OsMYB30 was amplified with the primers pMAL-OsMYB30F and pMAL-OsMYB30R shown in SI Appendix, Table S2, and the PCR products were cloned into the pMAL-c2X vectors (New England Biolabs, Inc.), resulting in the plasmid pMAL-OsMYB30.

Rice Transformation.

The genetic complementation and RNAi constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105, and subsequently transformed into the rice varieties 02428 and IR64, respectively. Plants regenerated from hygromycin-resistant calli (T0 plants) were grown in the field, and T1 seeds were obtained after self-pollination. The genotypes of each transgenic plant and their progenies were examined by PCR amplification, using gene-specific primers. At least 2 independent homozygous T2 transgenic plants identified with PCR and hygromycin resistance were used for BPH resistance test.

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR Analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from rice seedlings using the RNA prep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR assays were performed using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq RT-PCR Kit (Takara), following the manufacturer’s instructions, with the primers listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. Error bars indicate SD of 3 biological replicates.

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification.

MBP fusion protein purification was performed using the pMAL Protein Fusion and Purification System following the manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs).

Lignin Analysis.

Cell wall isolation was performed as described previously (34). Briefly, the stems of 1-mo-old plants were harvested individually. Stem pieces (1.5 g) were immediately frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen. After the addition of 30 mL of 50 mM NaCl, the mixture was kept at 4 °C overnight and then centrifuged for 10 min at 3,500 rpm. The pellet was extracted with 40 mL of 80% ethanol and sonicated for 20 min. This procedure was repeated twice. The same centrifugation, extraction, and sonication steps were performed with acetone, chloroform:methanol (1:1), and acetone. For lignin content measurement, the acetyl bromide-soluble lignin method was performed as described previously (21). Error bars indicate SD of 3 biological replicates.

For cellular observation of lignin, fresh hand-cut specimens were excised from rice leaf sheath at the heading stage, fixed, sectioned, and stained by phloroglucinol-HCl (3% (wt/vol) phloroglucinol in ethanol:12 N HCL in a 1:2 ratio) as described previously (35). The stained sections were visualized under an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). At least 20 sections were observed for each cultivar or line.

Measurement of SA.

SA was measured with the biosensor strain of Acinetobacter species, ADPWH_lux, as described previously (36, 37). For the standard curve, 0.1 g NahG transgenic fresh seedlings were frozen with liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 200 μL 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5.6), then centrifuged at 12, 000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Then the supernatant was used to dilute the SA stock (0 to 1, 000 μg/mL): 1 μL SA stock was diluted 10-fold with the NahG transgenic line extract (22), and 5 μL each of SA stock, 60 μL LB, and 50 μL Acinetobacter sp. ADPWHlux (OD = 0.4) were added to the wells of the plate. SA standards were recorded in parallel with the experimental samples.

To measure the SA content, 0.1 g fresh seedlings were frozen with liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 200 μL 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5.6), then centrifuged at 12, 000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and 0.1 μL supernatant was diluted with 44 μL acetate buffer in a new tube. In addition, 60 μL LB media, 5 μL plant extract, and 50 μL Acinetobacter sp. ADPWH-lux (OD = 0.4) were added to each well of a black 96-well plate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and luminescence was read by a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices). Error bars indicate SD of 3 biological replicates.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Experiments.

Biacore T200 and CM5 chips (GE Healthcare) with cross-linked anti-biotin rabbit polyclonal antibodies (abcam, ab1227) were used for all Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments. The instrument was first primed 3 times with the reaction buffer, and flow cell 1 (FC1) was used as the reference flow cell, which was unmodified and lacked the oligonucleotide. Flow cell 2 (FC2) was used for immobilization of the oligonucleotide. The biotin-labeled oligonucleotide was injected during a 1-min period at a flow rate of 5 μL⋅min−1, and immobilization levels of 200 to 300 RU were routinely observed under these conditions. Protein–DNA binding assays were performed in the reaction buffer at the relatively high flow rate of 10 μL⋅min−1 to avoid or minimize any mass-transport limitation effects. Protein solutions (15 nM, 30 nM, 60 nM, 120 nM, and 240 nM) were injected for 120 s, followed by dissociation in the reaction buffer for 60 s. At the end of the dissociation period, the sensor chip was regenerated to remove any remaining bound materials by injecting the reaction buffer, containing 15 mM NaOH, at 30 μL⋅min−1 for 300 s. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay.

To generate the pOsPAL6:LUC and pOsPAL8:LUC reporter constructs, about 2 kb of the OsPAL6 and OsPAL8 promoters were cloned into the pGreenII-0800-LUC vector. Full-length cDNA of OsMYB30 was cloned into the modified pAN580 binary vector. The constructs were cotransformed into rice protoplasts. The luciferase activity was calculated following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega), and the data presented are the averages of 3 biological replicates.

EMSA.

For the EMSA, a modified 5′-biotin-binding oligonucleotide probe containing the AC-like element was synthesized. Recombinant OsMYB30 protein was purified before the binding experiment. EMSA assay was manipulated following the LightShift EMSA Optimization and Control Kit instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Detection of biotin on the probe by streptavidin was carried out using a Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The experiment was repeated 3 times, with similar results each time.

PAL activity assay.

PAL activity was assayed according to the method described by Cheng et al. (38), with minor modifications. About 1 g 2-wk-old seedlings were homogenized in 10 mL ice-cold extraction (1 mM EDTA, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1% PVP, and 0.1 M sodium borate buffer). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12, 000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used as the crude enzyme extract. 0.2 mL of supernatant with 1 mL of 20 mM l-phenylalanine and 2.8 mL of 0.1 mM sodium borate buffer (pH 8.8) was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.2 mL 2 M HCl. The absorbance of the samples was recorded using a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices) at a wavelength of 290 nm. The increase of 0.01 unit in absorbance per hour was defined as 1 unit of enzyme activity (U). PAL activity was listed as U⋅h−1⋅mg−1 FW. Error bars indicate SD of 3 biological replicates.

Data Availability.

The microarray data included in this article have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSM4174171–GSM4174178).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We owe special thanks to Professor G. An (Department of Plant Systems Biotech, Kyung Hee University, Korea) for providing the rice transcription factor T-DNA mutants, to Professor Chengcai Chu (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing) for providing NahG lines, and to Dr. Hui Wang (Natural Environment Research Council/Centre for Ecology and Hydrology-Oxford, Oxford, UK) for providing the SA biosensor strain Acinetobacter sp. ADPWH_lux and technical assistance with the SA measurement. The National Key Transformation Program (Grant 2016ZX08001-001), National Key Research Program (Grant 2016YFD0100600), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grants 31522039 and 31471470), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grants KJYQ201602 and JCQY201902) supported this work. We also acknowledge support from the Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production cosponsored by Jiangsu Province and Ministry of Education, and the Key Laboratory of Biology, Genetics and Breeding of Japonica Rice in Mid-lower Yangtze River, Ministry of Agriculture, People’s Republic of China.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: A complete set of microarray data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSM4174171–GSM4174178).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1902771116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rivera C. T., Ou S. H., Lida T. T., Grassy stunt disease of rice and its transmission by Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). Plant Dis. Rep. 50, 453–456 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling K. C., Tiongco E. R., Aguiero V. M., Rice ragged stunt, a new virus disease. Plant Dis. Rep. 62, 701–705 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du B., et al. , Identification and characterization of Bph14, a gene conferring resistance to brown planthopper in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22163–22168 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y., et al. , Allelic diversity in an NLR gene BPH9 enables rice to combat planthopper variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 12850–12855 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., et al. , A gene cluster encoding lectin receptor kinases confers broad-spectrum and durable insect resistance in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 301–305 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo J., et al. , Bph6 encodes an exocyst-localized protein and confers broad resistance to planthoppers in rice. Nat. Genet. 50, 297–306 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., et al. , Map-based cloning and characterization of BPH29, a B3 domain-containing recessive gene conferring brown planthopper resistance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 6035–6045 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren J., et al. , Bph32, a novel gene encoding an unknown SCR domain-containing protein, confers resistance against the brown planthopper in rice. Sci. Rep. 6, 37645 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulbat K., The role of phenolic compounds in plant resistance. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 80, 97–108 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z., Zheng Z., Huang J., Lai Z., Fan B., Biosynthesis of salicylic acid in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 4, 493–496 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X., et al. , Loss of function of a rice TPR-domain RNA-binding protein confers broad-spectrum disease resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 3174–3179 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q., Luo L., Zheng L., Lignins: Biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 335 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y., et al. , CmMYB19 over-expression improves aphid tolerance in Chrysanthemum by promoting lignin synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 619 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaman M. E., Copaja S. V., Argandoña V. H., Relationships between salicylic acid content, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity, and resistance of barley to aphid infestation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 2227–2231 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith C. M., Boyko E. V., The molecular bases of plant resistance and defense responses to aphid feeding: Current status. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 122, 1–16 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han Y., et al. , Constitutive and induced activities of defense-related enzymes in aphid-resistant and aphid-susceptible cultivars of wheat. J. Chem. Ecol. 35, 176–182 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan J., et al. , The tyrosine aminomutase TAM1 is required for β-tyrosine biosynthesis in rice. Plant Cell 27, 1265–1278 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen M. B., et al. , Brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, resistance in rice cultivar IR64: Mechanism and role in successful N. lugens management in Central Luzon. Philippines. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 85, 221–229 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng X., Zhu L., He G., Towards understanding of molecular interactions between rice and the brown planthopper. Mol. Plant 6, 621–634 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X., Liu C. J., Multifaceted regulations of gateway enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids. Mol. Plant 8, 17–27 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohde A., et al. , Molecular phenotyping of the pal1 and pal2 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals far-reaching consequences on phenylpropanoid, amino acid, and carbohydrate metabolism. Plant Cell 16, 2749–2771 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang J., et al. , Semi-dominant mutations in the CC-NB-LRR-type R gene, NLS1, lead to constitutive activation of defense responses in rice. Plant J. 66, 996–1007 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onyilagha J. C., Lazorko J., Gruber M. Y., Soroka J. J., Erlandson M. A., Effect of flavonoids on feeding preference and development of the crucifer pest Mamestra configurata Walker. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 109–124 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernays E. A., Cooper-Driver G., Bilgener M., Herbivores and plant tannins. Adv. Ecol. Res. 19, 263–302 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaille C., Kast P., Haas D., Salicylate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Purification and characterization of PchB, a novel bifunctional enzyme displaying isochorismate pyruvate-lyase and chorismate mutase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 21768–21775 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wildermuth M. C., Dewdney J., Wu G., Ausubel F. M., Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 414, 562–565 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcion C., et al. , Characterization and biological function of the ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147, 1279–1287 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogawa D., et al. , The phenylalanine pathway is the main route of salicylic acid biosynthesis in Tobacco mosaic virus-infected tobacco leaves. Plant Biotechnol. 23, 395–398 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pallas J. A., Paiva N. L., Lamb C., Dixon R. A., Tobacco plants epigenetically suppressed in phenylalanine ammonia-lyase expression do not develop systemic acquired resistance in response to infection by tobacco mosaic virus. Plant J. 10, 281–293 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J., et al. , Functional analysis of the Arabidopsis PAL gene family in plant growth, development, and response to environmental stress. Plant Physiol. 153, 1526–1538 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandurska H., Cieslak M., The interactive effect of water deficit and UV-B radiation on salicylic acid accumulation in barley roots and leaves. Environ. Exp. Bot. 94, 9–18 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee B. R., et al. , Peroxidases and lignification in relation to the intensity of water-deficit stress in white clover (Trifolium repens L.). J. Exp. Bot. 58, 1271–1279 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinrichs E., Medrano F., Rapusas H., Genetic Evaluation for Insect Resistance in Rice (International Rice Research Institute, Philippines, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukushima R. S., Hatfield R. D., Extraction and isolation of lignin for utilization as a standard to determine lignin concentration using the acetyl bromide spectrophotometric method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 3133–3139 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam P. Y., et al. , Disrupting flavone synthase II alters lignin and improves biomass digestibility. Plant Physiol. 174, 972–985 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang W. E., et al. , Chromosomally located gene fusions constructed in Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 for the detection of salicylate. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1339–1348 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang W. E., et al. , Quantitative in situ assay of salicylic acid in tobacco leaves using a genetically modified biosensor strain of Acinetobacter sp. ADP1. Plant J. 46, 1073–1083 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng G. W., Breen P. J., Activity of phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL) and concentrations of anthocyanins and phenolics in developing strawberry fruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 116, 865–869 (1991). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The microarray data included in this article have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSM4174171–GSM4174178).