Significance

While numerous studies analyze the strategy of online influence campaigns, their impact on the public remains an open question. We investigate this question combining longitudinal data on 1,239 Republicans and Democrats from late 2017 with data on Twitter accounts operated by the Russian Internet Research Agency. We find no evidence that interacting with these accounts substantially impacted 6 political attitudes and behaviors. Descriptively, interactions with trolls were most common among individuals who use Twitter frequently, have strong social-media “echo chambers,” and high interest in politics. These results suggest Americans may not be easily susceptible to online influence campaigns, but leave unanswered important questions about the impact of Russia’s campaign on misinformation, political discourse, and 2016 presidential election campaign dynamics.

Keywords: misinformation, social media, political polarization, computational social science

Abstract

There is widespread concern that Russia and other countries have launched social-media campaigns designed to increase political divisions in the United States. Though a growing number of studies analyze the strategy of such campaigns, it is not yet known how these efforts shaped the political attitudes and behaviors of Americans. We study this question using longitudinal data that describe the attitudes and online behaviors of 1,239 Republican and Democratic Twitter users from late 2017 merged with nonpublic data about the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) from Twitter. Using Bayesian regression tree models, we find no evidence that interaction with IRA accounts substantially impacted 6 distinctive measures of political attitudes and behaviors over a 1-mo period. We also find that interaction with IRA accounts were most common among respondents with strong ideological homophily within their Twitter network, high interest in politics, and high frequency of Twitter usage. Together, these findings suggest that Russian trolls might have failed to sow discord because they mostly interacted with those who were already highly polarized. We conclude by discussing several important limitations of our study—especially our inability to determine whether IRA accounts influenced the 2016 presidential election—as well as its implications for future research on social media influence campaigns, political polarization, and computational social science.

Though scholars once celebrated the potential of social media to democratize public discourse about politics, there is growing concern that such platforms facilitate uncivil behavior (1–4). The relatively anonymous nature of social-media interactions not only reduces the consequences of incivility—it also enables social-media users to impersonate others in order to create social discord (5). Though such subterfuge is commonplace across the internet, there is increasing alarm about coordinated campaigns by Russia and other countries to fan political polarization in the United States. These campaigns reportedly involve vast social-media armies that impersonate Americans and amplify debates about divisive social issues such as immigration and gun control (6–8).

This study provides a preliminary assessment of how the Russian government’s social-media influence campaign shaped the political attitudes and behaviors of American Twitter users in late 2017. According to the US Senate Intelligence Committee, Russia has used social-media platforms to attack its political enemies since 2013 under the auspices of an organization known as the Internet Research Agency (IRA). Scholars have argued that these campaigns against the United States were multifaceted and, more specifically, designed to “exploit societal fractures, blur the lines between reality and fiction, erode…trust in media entities…and in democracy itself” (9). A rapidly expanding literature examines the breadth and depth of IRA activity on social media to gain insight into Russian social-influence strategies (6, 7, 9). Yet, to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether these efforts actually impacted the attitudes and behaviors of the American public (10, 11). Our study is an initial attempt to fill this research gap.

Popular wisdom indicates that Russia’s social-media campaign exerted profound influence on the political attitudes and behaviors of the American public. This is perhaps because of the sheer scale and apparent sophistication of this campaign. In 2016 alone, the IRA produced more than 57,000 Twitter posts, 2,400 Facebook posts, and 2,600 Instagram posts—and the numbers increased significantly in 2017 (6). There is also anecdotal evidence that IRA accounts succeeded in inspiring American activists to attend rallies (12). The scope of this effort prompted The New York Times to describe the Russian campaign as “the Pearl Harbor of the social media age: a singular act of aggression that ushered in an era of extended conflict” (13).

Studies that examine the content of Russia’s social-media campaign reveal that it was primarily designed to hasten political polarization in the United States by focusing on divisive issues such as police brutality (14, 15). According to Stella et al. (8), such efforts “can deeply influence reality perception, affecting millions of people’s voting behavior. Hence, maneuvering opinion dynamics by disseminating forged content over online ecosystems is an effective pathway for social hacking.” Howard et al. (6) similarly argue that “the IRA Twitter data shows a long and successful campaign that resulted in false accounts being effectively woven into the fabric of online US political conversations right up until their suspension. These embedded assets each targeted specific audiences they sought to manipulate and radicalize, with some gaining meaningful influence in online communities after months of behavior designed to blend their activities with those of authentic and highly engaged US users.” Such conclusions are largely based upon qualitative analyses of the content produced by IRA accounts and counts of the number of times Twitter users engaged with IRA messages.

That sizable populations interacted with IRA messages on Twitter, however, does not necessarily mean that such messages influenced public attitudes. Foundational research in political science, sociology, and social psychology provides ample reason to question whether the IRA campaign exerted significant impact. Studies of political communication and campaigns, for example, have repeatedly demonstrated that it is very difficult to change peoples’ views (16). Political messages tend to have “minimal effects” because the individuals most likely to be exposed to persuasive messages are also those who are most entrenched in their views (17). In other words, if only Twitter users with very strong political views are exposed to IRA trolls, it might not make their views any more extreme. An extensive literature confirms that such “minimal effects” are the norm in political advertising—even when microtargeting of ads to users is employed (18). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis concludes that the average treatment effect of political campaigning is precisely zero (19). If American political agents struggle to persuade voters, it seems that foreign agents might struggle even more to influence public opinion—not only because the relatively anonymous nature of social-media interactions may raise issues of source credibility, but also because of linguistic and cultural barriers that undoubtedly make the development of persuasive messaging more challenging.

Still, previous studies of IRA activity indicate that the organization not only aimed to persuade voters to support a particular candidate or policy, but also impersonated stereotypes about Republicans and Democrats in order to increase affective political polarization (6). Such efforts could have indirect effects beyond changing issue attitudes. There is some evidence, for example, that reactions to social-media messages can have a strong impact on audiences above and beyond the messages themselves (20). Observing a trusted social-media contact argue with an IRA account that impersonates a member of the opposing political party, for example, could thus contribute to stereotypes about the other side. Even if the trolls did not exacerbate ideological polarization, that is, they may have abetted affective polarization (21). Finally, there is some evidence that IRA accounts were not only aiming to influence attitudes, but also political behaviors. For example, some studies indicate that the IRA attempted to demobilize African-American voters by spreading negative messages about Hillary Clinton prior to the 2016 US presidential election (6). Hence, any analysis of the impact of the IRA campaign must not only examine its direct impact upon Americans’ opinions about policy issues, but also their attitudes toward each other and their overall level of political engagement. Our study is thus designed to scrutinize whether interactions with IRA trolls shaped the issue attitudes, partisan stereotypes, and political behaviors of a large group of American social-media users.

Research Design

Perhaps the most valid research design for studying the impact of Russia’s social-media campaign would be to dispatch troll-style messages as part of a field experiment on a social-media platform. Needless to say, such a study would be highly unethical. Instead, we rely on observational methods that avoid such pitfalls, but provide a less direct estimate of the causal effect of IRA trolls. Our analysis leverages a longitudinal survey of 1,239 Republicans and Democrats who use Twitter frequently that was fielded in late 2017 by Bail et al. (3). Though this study was designed for other purposes, unhashed, restricted-access data provided to us by Twitter’s Elections Integrity Hub allowed us to identify individuals who interacted with IRA accounts between survey waves. Thus, we have political attitudes measured preinteraction and postinteraction, allowing us to estimate individual-level changes in political attitudes and behaviors over time.

In October 2017, Bail et al. (3) hired the survey firm YouGov to interview members of its large online panel who 1) identify as either a Republican or a Democrat; 2) visit Twitter at least 3 times a week; 3) reside within the United States; 4) were willing to share their Twitter handle or ID; and 5) did not set their account to protected, or a nonpublic setting. Respondents were also stratified in order to recruit approximately equal numbers of respondents who identify as “strong” or “weak” partisans. Readers should therefore note that this sample is not representative of the general US population and does not include independent voters (see SI Appendix for a full comparison of the demographics of our sample compared to the general population).

Respondents were paid the equivalent of $11 for completing this survey via the survey firm’s points system. In November 2017, all survey respondents were offered $12 to complete a follow-up survey with the same battery of questions fielded in the original survey. The study by Bail et al. (3) also involved a field experiment. In the period between the 2 surveys just described, respondents were randomized into a treatment condition where they were offered financial incentives to follow a Twitter bot created by the authors that was designed to expose them to messages from opinion leaders from the opposing political party. Our analysis accounts for this design, and we provide a more detailed description of the sampling procedure, survey attrition, and other research design issues in SI Appendix. The bots of Bail et al. (3) did not retweet any messages from IRA troll accounts.

Both of the surveys of Bail et al. (3) included a series of questions about political attitudes that we used to measure 4 of the 6 outcomes analyzed below. The survey included 2 measures of affective political polarization: a feeling thermometer, where respondents were asked to rate the opposing political party on a scale of 0 to 100; and a social distance scale, where respondents were asked whether they would be unhappy if a member of the opposing political party married someone in their family or if they had to socialize or work closely with a member of the opposing party. The surveys also included 2 measures of ideological polarization: a 7-point ideology scale, where respondents were asked to place themselves on a continuum that ranges from “liberal” to “conservative”; and a 10-item index that asked respondents to agree or disagree with a series of liberal- or conservative-leaning statements. The ideological polarization measures were coded such that positive values represent increasing ideological polarization and negative values represent decreasing polarization. The full text of these questions is available in SI Appendix.

Because previous studies indicate that interaction with IRA accounts may lead people to detach themselves from politics, our analysis also includes 2 behavioral outcomes observed from respondents’ Twitter accounts. First, we counted the number of political accounts each user followed before and after the 2-wave survey. Political accounts were identified via a network-sampling method that built a sample of 4,176 “opinion leaders” who are elected officials or people who are followed by elected officials (22). Second, we included a measure of the ideological bias of each respondent’s Twitter network that calculated the percentage of political accounts the respondent followed that shared the respondent’s party identification using the same network-based opinion leader sample just described. We provide a more detailed description of this ideological scoring system in SI Appendix.

The key independent variable in our models is a binary indicator of whether respondents interacted with IRA accounts between the 1st and 2nd survey described above. We constructed this measure as follows. First, we obtained numeric account identifiers associated with all IRA accounts via the Twitter source described above. These accounts were identified through the joint work of Twitter and the US Senate Intelligence Committee in early 2018. A public version of these data is currently available, but it does not describe numeric identifiers for most accounts. We requested and received the unhashed dataset from Twitter, which currently consists of 4,256 IRA accounts.

We operationalized troll interactions as inclusive of both direct engagements with a troll (liking a troll tweet, retweeting a troll tweet, or liking a tweet that mentions a troll but was not produced by a troll) and indirect engagements, or activities that could reasonably lead to viewing a troll’s tweets (following a troll or being exposed to a troll’s message when a respondent’s friend mentions a troll in their tweet). We provide detailed information about the distribution of these different types of interactions across respondents (and over time) in SI Appendix. Overall, the Twitter data show that 19.0% of our respondents interacted with IRA accounts, and 11.3% directly engaged with troll accounts. During the month between our survey waves, 3.7% of respondents interacted with an IRA account for the first time, providing leverage for estimating the impact of those engagements. By comparison, Twitter reported that 1.4 million of its 69 million monthly active users had interacted with IRA accounts in early 2018, or approximately 2%. The elevated rate of IRA interaction within our sample may reflect higher levels of political interest among respondents, since only partisans were invited to participate in the original study (recall, however, that our sample was stratified to include both strong and weak partisans).

One limitation of our measure of troll interaction is that it does not capture all types of exposure to IRA accounts. Though our measure identifies people who follow troll accounts—or who follow people who mention troll accounts—we cannot verify that these people actually viewed such messages or how long they viewed them. A further limitation of our measure is that it does not include retweets of IRA messages by those who were followed by respondents in our study, since Twitter deleted such retweets alongside the original IRA messages themselves. In addition, the trolls in our sample occasionally retweeted content by nontrolls. In some cases, we were not able to determine whether our respondents were exposed to such messages via trolls or other Twitter users. We performed a sensitivity analysis which indicated that these missing measures would be unlikely to impact our substantive findings below—in part because retweets are a far less common form of engagement with IRA accounts than mentions (SI Appendix).

Our models also included a series of control variables to account for confounding factors that might influence political attitudes and behaviors. These measures were either collected by the original study of Bail et al. (3), made through observation of respondents’ Twitter behavior, or provided via the survey firm’s own panel profile data. These include 1) a binary indicator that describes whether the respondent identifies as a Republican; 2) a 4-point measure of frequency of Twitter usage where higher scores indicate greater frequency; 3) a measure of overall news interest derived from the following question: “Some people seem to follow what’s going on in government and public affairs most of the time, whether there’s an election going on or not. Others aren’t that interested. Would you say you follow what’s going on in government and public affairs …[hardly at all, only now and then, some of the time, or most of the time]?”; 4) respondent’s year of birth; 5) a continuous measure of family income; and 6) binary variables that indicate whether the respondent is male, has a college degree, is white, or is located in 1 of 4 geographic regions in the United States. Finally, all models reported below include a binary indicator that describes whether the respondent was assigned to the experimental treatment condition in the original study of Bail et al. (3).

Findings

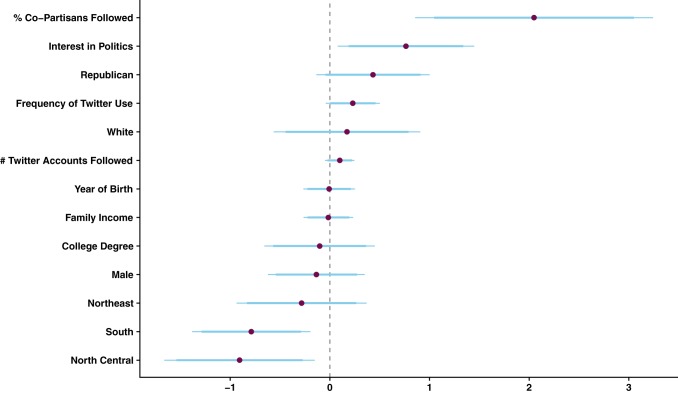

Before analyzing the impact of interactions with IRA accounts on our outcome variables, we first employed binomial regression models to identify the characteristics of those who interacted with IRA accounts. The outcome in this model is a binary indicator that describes whether or not the respondent interacted with an IRA account prior to the 1st survey conducted by Bail et al. (3) in October 2017 by mentioning, retweeting, liking, or following an IRA account or liking a tweet that mentions an IRA account (76 of 1,239 respondents). Fig. 1 presents standardized coefficients from this model, showing that the strongest predictor of IRA interaction is the strength of respondents’ echo chambers (measured as the percentage of political accounts they follow that lean toward the respondent’s own political party). The 2nd strongest predictor of IRA interaction is overall political interest, followed by frequency of Twitter usage. Though Republicans appeared more likely to interact with IRA accounts than Democrats, this association is not statistically significant. To summarize, our initial analysis indicates that the respondents most likely to interact with trolls were those who may be least susceptible to persuasion effects—because of their more entrenched political views.

Fig. 1.

Binomial regression model predicting interaction with Twitter accounts associated with the Russian IRA. Purple circles describe standardized point estimates, and blue lines describe 90% and 95% CIs. Survey respondents with strong ideological homophily in their Twitter network, high interest in politics, and who use Twitter more than once a day were most likely to interact with IRA accounts.

To estimate the impact of interacting with IRA accounts on our 6 outcome measures, we modeled change in each of our attitudinal and behavioral variables between the 1st and 2nd surveys; treatment was measured as a binary variable indicating whether the survey respondent interacted with IRA accounts. We employed Bayesian regression trees to estimate average treatment effects upon treated respondents (or ATTs), as well as heterogeneous treatment effects by other covariates in the models. This family of techniques uses nonparametric Bayesian regression to reduce dimensionally adaptive random basis elements. More specifically, we employed the Bayesian causal forest (BCF) model (23), which incorporates an estimate of the propensity function within the response model that amounts to a covariate-dependent prior on the regression function. This technique is particularly well suited to identify heterogeneous treatment effects by allowing treatment heterogeneity to be regularized separately by each control variable in the model. We omitted individuals who interacted with trolls prior to the 1st survey wave, leaving 44 individuals treated and 1,106 in the control group for the main models presented below. We conducted 3 additional sets of analyses that expanded the number of treated cases considerably—a less conservative operationalization of treatment in which pretreated individuals were included (SI Appendix), a synthetic treatment measure in the sensitivity analysis (SI Appendix), and an expanded time frame using additional survey data presented below—with no change in results.

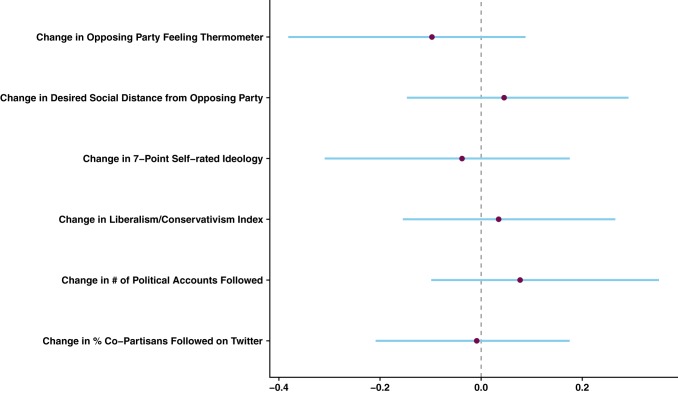

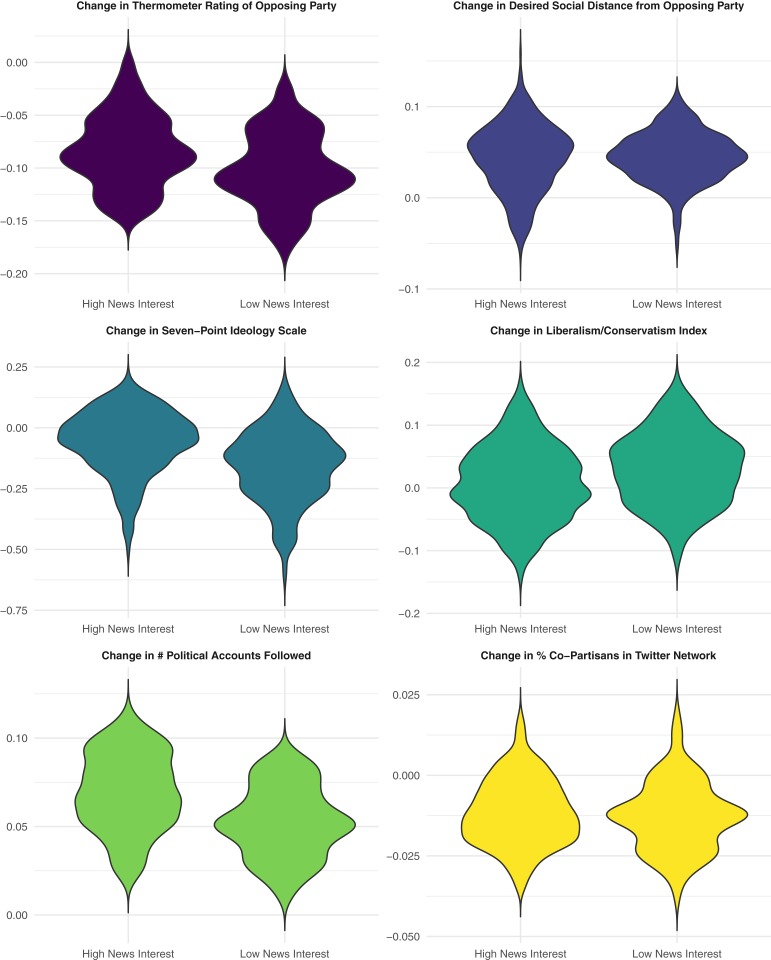

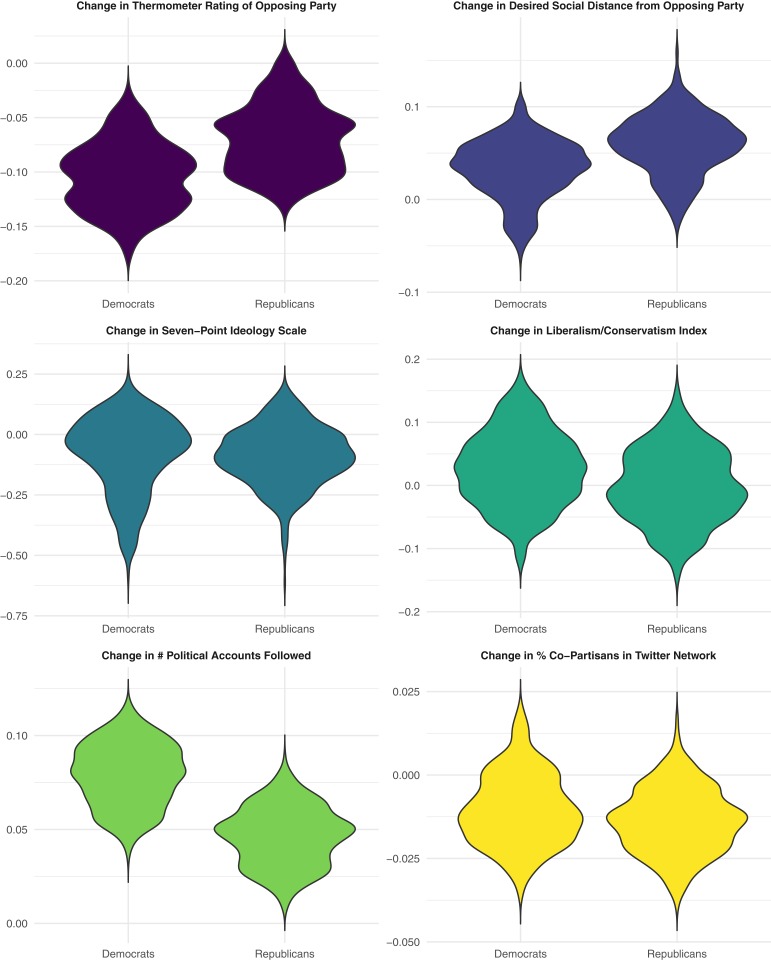

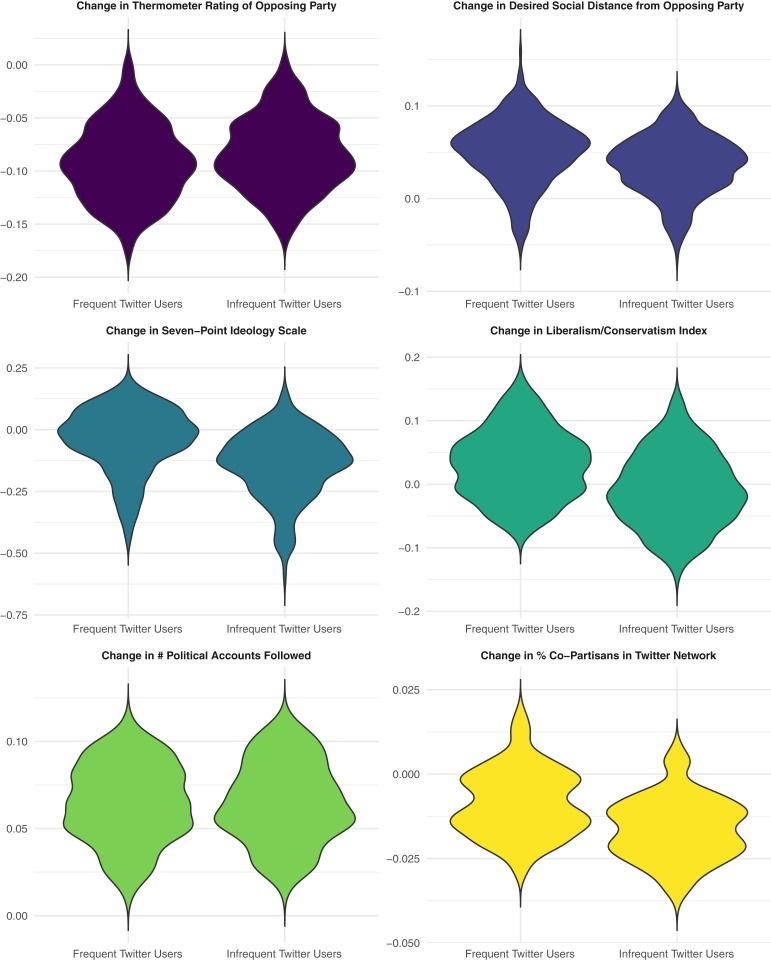

Fig. 2 reports the ATTs of interacting with IRA accounts on each of the outcomes in our model with intervals derived from the 97.5th and 2.5th quantiles, respectively. These effects were standardized to have a mean of 0 and SD of 1 to facilitate interpretation. As this figure shows, IRA interaction did not have a significant association with any of our 6 outcome variables. Figs. 3–5 plot the individual treatment effects of troll interaction against the variables associated with troll interaction, collapsed into binary categories to facilitate interpretation. Fig. 3 shows no substantial differences in the effect of troll interactions, according to level of political interest across each of our outcomes. Figs. 4 and 5 report no substantial differences for frequency of Twitter usage or party identification, though there is a suggestive difference between Republicans and Democrats in change in the number of political accounts that respondents followed. We observed no other heterogeneous treatment effects by all other covariates in our models either (SI Appendix).

Fig. 2.

BCF models describing the effect of interacting with Russian IRA accounts on change in political attitudes and behaviors of Republican and Democratic Twitter users who responded to 2 surveys fielded between October and November 2017. Purple circles describe the average treatment effects on the treated, and blue lines describe 95% credible intervals. Interaction with IRA accounts has no significant effect on all 6 outcomes.

Fig. 3.

Individual effects of interacting with Russian IRA accounts on political attitudes and behavior by level of news interest using BCFs.

Fig. 5.

Individual effects of interacting with Russian IRA accounts on political attitudes and behavior by partisan identification using BCFs.

Fig. 4.

Individual effects of interacting with Russian IRA accounts on political attitudes and behavior by frequency of Twitter usage using BCFs.

Assessing Dosage Effects over an Extended Time Period

Our results show no evidence that interacting with Russian Twitter trolls influenced the attitudes or behaviors of Republicans and Democrats who use Twitter at least 3 times a week, but the analyses are limited in several ways. First, our measure of interactions is restricted to the time period between October and November 2017. Yet, Twitter suspended many of these accounts in early 2017, dropping the number of IRA accounts that were regularly active each day from approximately 300 to 100. Seventy-five percent of the troll accounts our respondents interacted with were created prior to the crackdown—and had large followings, suggesting that they were particularly effective at avoiding detection—but it is important to consider the possibility that we would have found a bigger impact if our interactions went back further in time. A 2nd limitation is that our treatment measure is binary, but we might expect a greater effect from multiple interactions (a dosage effect). Likewise, we might expect variation in the impact based on the nature of the interaction; direct engagement with a tweet (e.g., liking, retweeting, or mentioning a tweet) might have more influence than an indirect engagement (e.g., following a troll or a friend mentions a troll).

To address these concerns, we obtained additional survey data collected as part of YouGov profile surveys outside of our 1-month study window. Unfortunately, the only relevant survey question consistently measured in profile surveys across this time period was a 5-point ideology scale, which we were able to obtain for all but 2 of our respondents. Of the outcomes considered in our earlier analysis, self-identified ideology might be somewhat less susceptible to persuasion, but it still allows for a test of ideological polarization across a wider time frame.

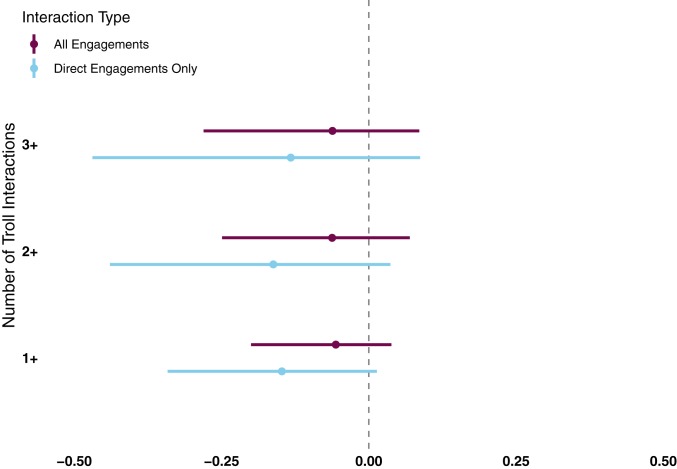

Treatment is defined as interacting with a troll between the earliest and latest measure of ideology available for each respondent in the YouGov profile dataset between February 2016 and April 2018. These models include the same specifications as those in the preceding analysis, including the exclusion of pretreated respondents who interacted with trolls prior to our first measure of ideology in the profile dataset. We ran separate models for different levels of dosage—with the treated group in each model defined as respondents who interacted with trolls 1 or more times (treated = 213, control = 1,017), 2 or more times (treated = 110, control = 1,120), or 3 or more times (treated = 67, control = 1,163). The larger size of the treatment group in this analysis allowed us to explore the effect of different types of interactions. While in the preceding analysis, we operationalized troll interactions as either direct or indirect engagement, the latter might not be sufficient to change political attitudes. Therefore, we also ran separate models in which treatment was operationalized only as direct engagement.

Fig. 6 reports the ATT and associated 95% credible intervals. As in the preceding models, measuring the effect of interacting with trolls on ideological polarization, positive coefficients represent increasing ideological polarization, while negative coefficients represent decreasing polarization. The outcome was again standardized to have a mean of 0 and SD of 1 to facilitate interpretation. Despite increasing the size of the treatment group substantially, we continued to find no significant effects of interacting with IRA trolls across all models and both types of interactions. The results showed no evidence of ideological polarization—if anything, though small and not statistically significant, the ATTs were negative.

Fig. 6.

Assessing dosage effects on self-reported ideology over an extended time period. Circles describe standardized point estimates, and lines describe 95% credible intervals for different amounts of direct and indirect engagement with IRA accounts. Here, again, interactions with troll accounts over an extended period show no significant association with ideological polarization.

Conclusion

Coordinated attempts to create political polarization in the United States by Russia and other foreign governments have become a focus of public concern in recent years. Yet, to our knowledge, no studies have systematically examined whether such campaigns have actually impacted the political attitudes or behaviors of Americans. Analyzing one of the largest known efforts to date using a combination of unique datasets, we found no substantial effects of interacting with Russian IRA accounts on the affective attitudes of Democrats and Republicans who use Twitter frequently toward each other, their opinions about substantive political issues, or their engagement with politics on Twitter in late 2017.

Even though we find no evidence that Russian trolls polarized the political attitudes and behaviors of partisan Twitter users in late 2017, these null effects should not diminish concern about foreign influence campaigns on social media because our analysis was limited to 1 population at a single point in time. We were unable to systematically determine whether IRA trolls influenced public attitudes or behavior during the 2016 presidential election, which is widely regarded as a critical juncture for misinformation campaigns. It is also possible that the Russian government’s campaign has evolved to become more impactful since the late-2017 period upon which we focused.

A further limitation of our analysis is that it was restricted to people who identified with the Democratic or Republican party and use Twitter relatively frequently (at least 3 times a week). It is possible that trolls have a stronger influence on political independents or those more detached from politics in general (though we did not observe significant effects among those who expressed weak attachments to either party). Our study was also limited to the United States, whereas reports indicate that the IRA is active in many other countries as well. Finally, our analysis only examines Twitter. Though Twitter remains one of the more influential social-media platforms in the United States at the time of this writing—and was targeted by the Russian IRA far more than other social-media platforms—it has a substantially smaller user base than Facebook and offers a unique, and highly public, form of social-media engagement to its users. It is thus possible that Russian influence might have been more pronounced on other platforms with other types of audiences or other structures for user engagement.

Another limitation is that our analysis evaluated a limited set of political and behavioral outcomes. For example, we cannot determine if Russian trolls influenced candidate or media behavior or if they shaped public opinion in other ways, such as attitudes about societal trust or by changing the salience of political issues. We also could not study whether or not troll interaction shaped voting behavior—though future studies might be able to link our data to voter files. Finally, the observational nature of our study prevents rigorous identification of the causal impact of the IRA campaign. Because of these limitations, additional research is needed to validate our findings through studies of other social-media campaigns, other platforms, and with different research methods.

Despite these issues, our results offer an important reminder that the American public is not tabula rasa and may not be easily manipulated by propaganda. Our results show that even though active partisan Twitter users engaged with trolls at a substantially higher rate than reported by Twitter, the vast majority (80%) did not interact with an IRA account. And for those who did, these interactions represented a minuscule share of their Twitter activity—on average, just 0.1% of their liking, mentioning, and retweeting on Twitter. That interactions with trolls were such a small fraction of all Twitter engagements may further explain why we observed null effects above.

While there are myriad reasons to be concerned about the Russian trolling campaign—and future efforts from other foreign adversaries both online and offline—it is noteworthy that the people most at risk of interacting with trolls—those with strong partisan beliefs—are also the least likely to change their attitudes. In other words, Russian trolls may not have significantly polarized the American public because they mostly interacted with those who were already polarized.

We conclude by noting important implications of our study for future research on social media, political polarization, and computational social science (24). Given the high-profile nature of the Russian IRA efforts, it is critical to have systematic empirical assessment of the impact on the public. While there is still much to be learned, our study offers an important contribution to this understudied issue. In addition, our study contributes to the growing field of computational social science and, more specifically, provides an example of how conventional forms of research such as public opinion surveys can be fruitfully combined with observational text and network data collected from social-media sites in order to address complex phenomena such as the impact of social-media influence campaigns on political attitudes and behavior. Though further studies are urgently needed on this issue, we hope our contribution will provide a model to future researchers who aim to study this complex and multifaceted issue.

Materials and Methods

See SI Appendix for a detailed description of the materials and methods used within this study, additional robustness checks, and links to our replication materials. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Duke University and New York University. All participants provided informed consent. Data for this study can be accessed at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/UATZBA (25).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NSF and Duke University. We thank the Twitter Elections Integrity Hub for sharing data.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Data for this study can be accessed at Harvard Dataverse, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/UATZBA.

See Commentary on page 21.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1906420116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sunstein C. R., # Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakshy E., Messing S., Adamic L. A., Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348, 1130–1132 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bail C. A., et al. , Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9216–9221 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guess A., Nagler J., Tucker J., Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau4586 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips W., This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard P. N., Ganesh B., Liotsiou D., Kelly J., François C., “The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018” (Working Paper 2018.2, Project on Computational Propaganda, Oxford, 2018). https://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2018/12/The-IRA-Social-Media-and-Political-Polarization.pdf. Accessed 13 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linvill D. L., Warren P. L., “Troll factories: The internet research agency and state-sponsored agenda building” (Working paper, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, 2018). http://pwarren.people.clemson.edu/Linvill_Warren_TrollFactory.pdf. Accessed 13 November 2019.

- 8.Stella M., Ferrara E., De Domenico M., Bots increase exposure to negative and inflammatory content in online social systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 12435–12440 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiResta R., et al. , “The tactics & tropes of the Internet Research Agency” (White paper, New Knowledge, Austin, TX, 2018; https://disinformationreport.blob.core.windows.net/disinformation-report/NewKnowledge-Disinformation-Report-Whitepaper.pdf).

- 10.Tucker J., et al. , “Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A Review of the scientific literature” (Tech. Rep., Hewlett Foundation, Menlo Park, CA, 2018).

- 11.Aral S., Eckles D., Protecting elections from social media manipulation. Science 365, 858–861 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson K. H., Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President What We Don’t, Can’t, and Do Know (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roose K., Social media’s forever war. NY Times, 17 December 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/17/technology/social-media-russia-interference.html. Accessed 13 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broniatowski D. A., et al. , Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1378–1384 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart L. G., Arif A., Starbird K., “Examining trolls and polarization with a retweet network” in Proceedings of WSDM Workshop on Misinformation and Misbehavior Mining on the Web (MIS2) (ACM, New York, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berelson B. R., Lazarsfeld P. F., McPhee W. N., McPhee W. N., Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1954). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaller J. R., The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endres K., Panagopoulos C., Cross-pressure and voting behavior: Results from randomized experiments. J. Politics 81, 1090–1095 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalla J. L., Broockman D. E., The minimal persuasive effects of campaign contact in general elections: Evidence from 49 field experiments. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 112, 148–166 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dounoucos V., Hillygus D. S., Carlson C., The message and the medium: An experimental evaluation of the effects of Twitter commentary on campaign messages. J. Inf. Technol. Polit. 16, 66–76 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyengar S., Westwood S. J., Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 690–707 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbera P., Birds of the same feather tweet together: Bayesian ideal point estimation using Twitter data. Political Anal. 23, 76–91 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hahn P. R., Murray J. S., Carvalho C., Bayesian regression tree models for causal inference: Regularization, confounding, and heterogeneous effects. arXiv:1706.09523 (23 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazer D., et al. , Life in the network: The coming age of computational social science. Science 323, 721–723 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bail C. A., et al. , Replication data for "Assessing the Russian Internet Agency’s impact on the political attitudes and behaviors of U.S. Twitter users in late 2017" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/UATZBA. Deposited 7 November 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.