Significance

Glutamate receptor-like (GLR) channels are plant homologs of glutamate receptors in vertebrate synapses; they are calcium-permeable channels involved in root and pollen tube growth, stomatal regulation, and wound signaling. This study presents crystal structures of a plant GLR ligand-binding domain (LBD) in complex with 4 different amino acid ligands and identifies the protein residues responsible for amino acid binding. Binding assays show that the amino acids that trigger GLR-mediated calcium influx in Arabidopsis thaliana root tip cells bind the GLR LBD with micromolar affinities.

Keywords: GLR channels, X-ray crystallography, binding assay, modeling, Ca2+ signaling

Abstract

Arabidopsis thaliana glutamate receptor-like (GLR) channels are amino acid-gated ion channels involved in physiological processes including wound signaling, stomatal regulation, and pollen tube growth. Here, fluorescence microscopy and genetics were used to confirm the central role of GLR3.3 in the amino acid-elicited cytosolic Ca2+ increase in Arabidopsis seedling roots. To elucidate the binding properties of the receptor, we biochemically reconstituted the GLR3.3 ligand-binding domain (LBD) and analyzed its selectivity profile; our binding experiments revealed the LBD preference for l-Glu but also for sulfur-containing amino acids. Furthermore, we solved the crystal structures of the GLR3.3 LBD in complex with 4 different amino acid ligands, providing a rationale for how the LBD binding site evolved to accommodate diverse amino acids, thus laying the grounds for rational mutagenesis. Last, we inspected the structures of LBDs from nonplant species and generated homology models for other GLR isoforms. Our results establish that GLR3.3 is a receptor endowed with a unique amino acid ligand profile and provide a structural framework for engineering this and other GLR isoforms to investigate their physiology.

Plant glutamate receptor-like (GLR) channels are plant homologs of mammalian ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) (1). iGluRs are homo- or heterotetrameric cation channels activated by the neurotransmitters l-glutamate, glycine, and d-serine released in the synaptic space. They are extensively studied for their central role in neurotransmission, learning, and memory (2).

The identification of iGluR homologs in other eukaryotes, including invertebrates and plants, and cyanobacteria has outlined the existence of a large family of GLR proteins across all kingdoms of life. In particular, the stoichiometry and architecture of plant GLRs are believed to be similar to iGluRs (3): Each subunit hosts an extracellular amino-terminal domain (ATD), an extracellular ligand-binding domain (LBD) composed of segments S1 and S2, 4 transmembrane helices (M1 to M4, 1 of which—M2—is not fully transmembrane), and a cytoplasmic tail (carboxyl-terminal domain; CTD), arranged in the order ATD-S1-M1-M2-M3-S2-M4-CTD (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The LBD has a conserved clamshell architecture resembling the periplasmic binding protein-like II superfamily in bacteria (4); in vertebrates, the binding of a ligand/agonist induces a variable degree of closure of the clamshell that pulls the transmembrane segments and opens the channel pore (2).

The 20 Arabidopsis thaliana GLR isoforms are grouped in 3 clades (5, 6). Specific isoforms have been implicated in several physiological processes, such as root growth (7), hypocotyl elongation (8), seed germination (9), long-distance wound signaling (10–12), pollen tube growth (13, 14), stomatal aperture (15, 16), as well as Ca2+ signaling (17–20); such isoforms are then considered Ca2+-permeable channels. In particular, the A. thaliana GLR3.3 isoform has been studied for its role in amino acid-induced cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) increases (17, 21), and recently recognized as a key player in glutamate-mediated defense signaling (11). Despite genetic data supporting the role of GLRs as amino acid receptors (11, 16–22), no biochemical binding assay has demonstrated that any plant GLR isoform can indeed bind glutamate or other ligands. Furthermore, whereas for iGluRs hundreds of X-ray structures are available for the LBD moiety (23) and an increasing number of cryoelectron microscopy full-length structures are accumulating (24–27) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), no structural information for any plant GLR isoform is available to date.

In the present study, we set out to investigate the role of A. thaliana GLR3.3 in the generation of amino acid-elicited cytosolic Ca2+ transients and reconstituted its ligand-binding domain in vitro. The determination of its selectivity profile by binding assays allowed us to identify the transient-eliciting amino acids as high-affinity ligands of the GLR3.3 LBD. Furthermore, we solved the crystal structures of the GLR3.3 LBD in complex with 4 representative ligands (l-glutamate, glycine, l-cysteine, l-methionine), providing structural information on plant GLR LBDs and a rational explanation for our in vitro affinity and in vivo functional data. Taken together, the reported results will guide rational mutagenesis in planta aimed at interfering with the GLR binding specificities to dissect their physiological properties.

Results

Arabidopsis Root Tip Cells Sense Exogenous Amino Acids by GLR3.3.

Glutamate (l-Glu) and other amino acids with surprisingly diverse side chains can elicit [Ca2+]cyt increases and plasma membrane (PM) depolarization in A. thaliana and rice seedlings (17–21, 28), as well as activate currents in the PM of guard cells (16) and pollen tubes (13). Genetic and pharmacological data provide evidence that the GLRs, working as ligand-gated channels, are responsible for the amino acid sensing and for the effects reported above (13, 16–20).

In this work, we confirmed the major role played by the GLR3.3 isoform (17, 18) in the generation of amino acid-induced (1 mM l-Cys, l-Glu, l-Ala, Gly, l-Ser, l-Asn, and l-Met) [Ca2+]cyt increases in Arabidopsis root tip cells by performing Ca2+ imaging experiments (by both light-sheet fluorescence and wide-field microscopy) on wild-type and 2 independent glr3.3 mutant (17) plants expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor NES-YC3.6 (29–31) (SI Appendix, Data and Figs. S2–S4). Remarkably, we confirmed the expression of GLR3.3 (by means of confocal microscopy) in those cells showing the amino acid-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 A–C′ and S3) and provided evidence about GLR3.3 Ca2+ permeability by yeast growth complementation assay (SI Appendix, Data and Fig. S5).

These data, which include confirmatory results, prompted us to investigate the biochemical properties of the isolated LBD of GLR3.3 to better clarify its role as amino acid receptor.

In Vitro Reconstitution and Characterization of the GLR3.3 LBD.

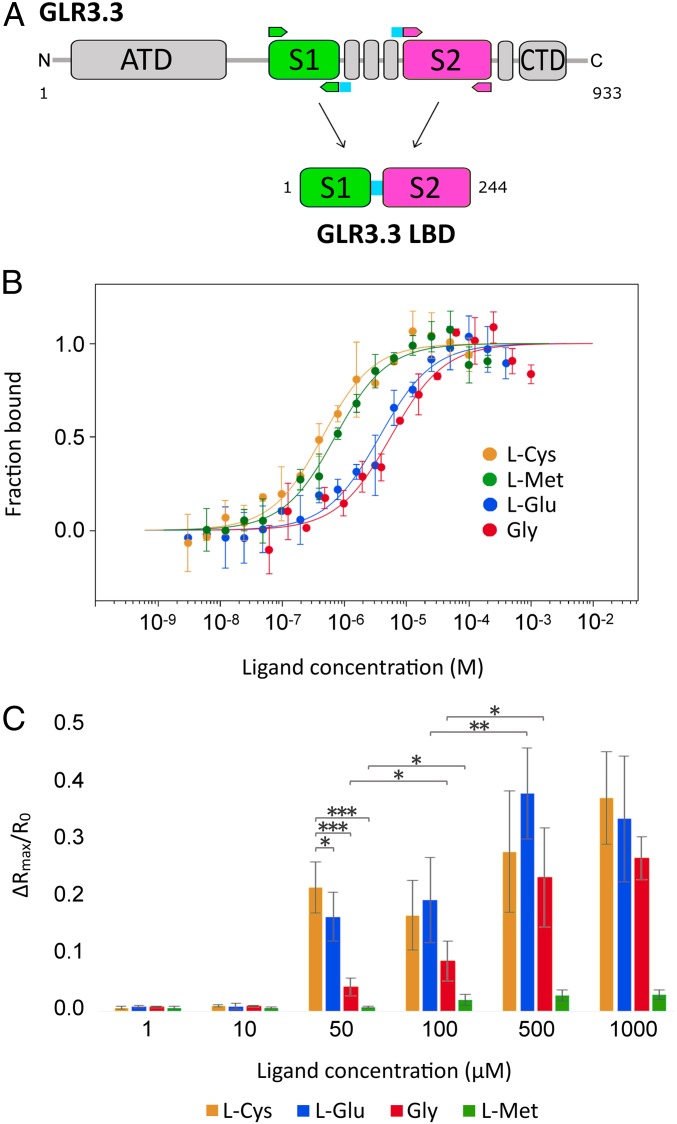

To investigate the role of GLR3.3 as a receptor and its specificity for amino acid ligands, we engineered a 244-residue fusion protein reproducing the GLR3.3 LBD, comprising segments S1 and S2 joined by a Gly-Gly-Thr linker, based on the successful structural determinations of iGluR LBD constructs (32). This sequence is conveniently numbered 1 to 244 throughout this work (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Fig. S1A). The boundaries of S1 and S2 were identified by alignment with a number of GLR/iGluR sequences from different species (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7).

Fig. 1.

Design of the AtGLR3.3 construct and characterization of its binding properties. (A) Design of the GLR3.3 LBD construct from the full sequence; arrows indicate the position of the cloning primers that introduce a short Gly-Gly-Thr linker (blue, between segments 1 and 2). (B) Fitting of the binding curves of l-Cys, l-Met, l-Glu, and Gly to the GLR3.3 LBD from the microscale thermophoresis experiments, based on the equation reported in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods; the graph reports the concentration of the ligand in logarithmic scale vs. the thermophoretic signal normalized as fraction-bound. (C) Maximal relative amplitude of cpVenus/CFP ratio as ΔR/R0 increase triggered by different concentrations of amino acids (dose-dependent amino acid response). n ≥ 3; error bars indicate ±SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005 (Student t test). For the 50, 100, 500, and 1,000 μM concentrations, differences in ΔRmax/R0 between incremental concentrations for the same ligand are statistically nonsignificant, unless indicated.

The resulting 27-kDa protein (GLR3.3 LBD) was purified in the presence of l-Glu and characterized (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Figs. S8 and S9); interestingly, circular dichroism experiments showed that the apo form of the protein, obtained through extensive dialysis, retains the same secondary structure content as the holo form, but with markedly lower thermal stability; reconstitution of the holo form, by addition of 70-fold excess l-Glu to the apo, restored its stability, thus highlighting 1) the occurrence of a reversible binding event and 2) the dominant role of the ligand in the structural stability of the holo form of the reconstituted LBD (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Multiple independent apo GLR3.3 LBD preparations were used to test the affinities of a number of amino acid ligands by microscale thermophoresis, producing consistent results (Fig. 1B and Table 1). Microscale thermophoresis monitors the migration of a fluorescently labeled protein across a temperature gradient in the presence of variable ligand concentrations (33). The panel of amino acid ligands was chosen to match the ones tested in planta by external administration. All in vitro affinity values were in the micromolar range, with the strongest binding measured for l-Cys and l-Met. Four amino acidic ligands (l-Glu, l-Ala, l-Asn, l-Ser) cluster in a group of similar affinity and the lowest affinity was measured for Gly. A low but detectable affinity was also recorded for d-Ser. No binding was detected for l-Trp that does not trigger any [Ca2+]cyt increase (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The l-Cys, l-Met, and l-Glu ligands were checked for absence of binding to a reference fluorescent target known to bind an unrelated low-molecular-weight ligand (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). These data point to a promiscuity of the GLR3.3 LBD binding site, with a marked preference for sulfur-containing amino acids (l-Cys, l-Met), a reduction of affinity in the absence of ligand side-chain β-atoms (Gly), and complete loss of binding in the case of a bulky side chain (l-Trp).

Table 1.

Values of the dissociation constant ± SD for the binding of a number of amino acid ligands to the GLR3.3 LBD, as determined by microscale thermophoresis

| Ligand | Kd, µM | n |

| l-Cys | 0.33 ± 0.14 | 2 |

| l-Met | 0.57 ± 0.17 | 2 |

| l-Glu | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 5 |

| l-Ala | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2 |

| l-Asn | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2 |

| l-Ser | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 3 |

| Gly | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 2 |

| l-Trp | No binding | 2 |

| d-Ser | 22 ± 6 | 1 |

The values reported are averages from n repeats.

The above-reported scale of in vitro affinity data on the isolated GLR3.3 LBD strongly resembles the [Ca2+]cyt increases measured in aequorin-expressing Arabidopsis seedlings challenged with different amino acids (18). However, the same scale of in vitro affinity data only partially matches our amino acid-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases in root tip cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). One of the possible reasons for this mismatch is that the measured GLR3.3 LBD binding affinities for amino acids are in the micromolar range, whereas administration to the Arabidopsis root tip was at 1 mM (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). This consideration prompted us to measure the root tip cell [Ca2+]cyt dynamics in response to lower doses of amino acids. We thus tested the in planta Ca2+ responses against 4 representative ligands (l-Cys, l-Glu, Gly, and l-Met) (Fig. 1C) at different concentrations. l-Cys, l-Glu, Gly, and l-Met ligands did not trigger any response at 1 and 10 µM and reached the plateau (evaluated in terms of peak maxima) between 100 and 500 µM. However, at 50 µM, l-Cys was more effective than l-Glu and Gly with no response to l-Met. For l-Cys, l-Glu, and Gly, our results mirror the different in vitro affinities also matching the results obtained in Arabidopsis seedlings expressing aequorin (figure 5B in ref. 18). However, 50 µM l-Met was unable to trigger a [Ca2+]cyt transient despite binding the GLR3.3 LBD at high affinity.

In conclusion, the different extents of [Ca2+]cyt increases evoked by different amino acids in Arabidopsis root tips can be for the most part correlated to the binding properties of the isolated GLR3.3 LBD. Therefore, we set out to obtain the crystallographic structure of the GLR3.3 LBD to identify the determinants underlying its peculiar selectivity profile.

Overall Structures of the GLR3.3 LBD.

The structure of the GLR3.3 LBD bound to l-Glu at 2.0-Å resolution was solved by molecular replacement in combination with single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (34, 35); the refined model was then used through molecular replacement to solve structures of the GLR3.3 LBD in complex with 3 different ligands (Gly, l-Cys, and l-Met, at resolutions of 1.6, 2.5, and 3.2 Å, respectively). All structures were refined to satisfactory R factor/Rfree values with good final stereochemistry (see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods, Fig. S11, and Table S1 for full details on structure solution and refinement).

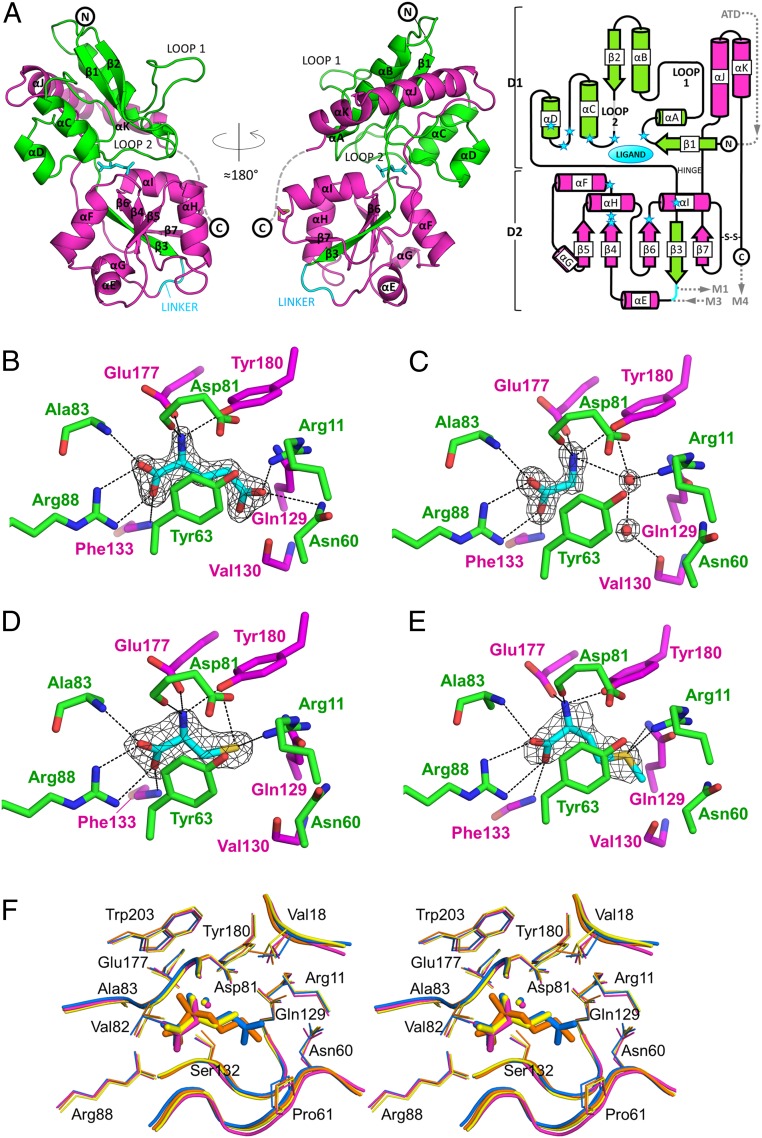

The GLR3.3 LBD displays a bilobed structure of ∼60 × 40 × 40 Å3, resembling the prokaryotic and eukaryotic LBDs described in the literature (Fig. 2A). Interrogation of the Dali server (36) (http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali/) identified as the most structurally related Protein Data Bank (PDB) records the LBDs from a group of vertebrate iGluRs of the kainate subtype (representative PDB ID code 1sd3, rmsd 2.4 Å, Z score 25.0) and the rotifer Adineta vaga GLR (AvGluR1, PDB ID code 4io2, rmsd 2.5 Å, Z score 24.9). Lobe 1 (hereafter called domain 1, residues 3 to 100 and 201 to 239) hosts 6 α-helices and 2 β-strands, whereas lobe 2 (hereafter called domain 2, residues 101 to 200) is built up by a central 5-stranded β-sheet surrounded by 5 α-helices. The structural core of each domain is secured by many π-interactions between aromatic side chains, produced by the presence of a remarkable number of Tyr and Phe residues (10 and 12, respectively), together accounting for 9% of all residues. The 2 domains are connected by a double-stranded hinge and separated by a deep cleft where the ligand binding pocket is located (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A–D). The binding pocket is inaccessible to solvent and has a volume of 196 Å3 as calculated by CASTp (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods) (http://sts.bioe.uic.edu/castp/) (37). Clear electron density corresponding to the ligand is present in the pocket of all our structures, thus allowing unambiguous positioning of each ligand and identification of their interactions (Fig. 2 B–E and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Two water molecules are always buried in the pockets, but do not contact the ligand; in the case of Gly, 2 additional water molecules are trapped at the site where the other amino acid ligands accommodate their side chains. The basic set for anchoring the invariant moiety of any amino acid ligand to the receptor is represented by 7 conserved interactions: The guanidino group of the evolutionarily invariant Arg88 chelates the α-carboxyl group of the ligand by a bidentate ionic interaction; the same α-carboxyl group is hydrogen-bonded with the main-chain N atoms of Ala83 and Phe133; and the α-amino group of the ligand is hydrogen-bonded with the Asp81 main-chain carbonyl and Tyr180 hydroxyl group, and involved in ionic interaction with the Glu177 side chain.

Fig. 2.

Structures of the AtGLR3.3 LBD bound to different ligands. (A) Overall structure of the AtGLR3.3 LBD (+l-Glu) in ribbon representation, colored to highlight the contributions of segments 1 (green) and 2 (magenta) to domains 1 and 2. The linker is colored cyan; l-Glu is in cyan sticks. The C-terminal stretch (dashed) has a defined electron density in 4 out of the 14 protein chains present in the different crystal forms. The structure is oriented in such a way that the N terminus (corresponding to the part of the polypeptide chain right after the ATD domain) is at the top and the linker (replacing the transmembrane segments M1 to M3) is at the bottom. The conventional secondary structure nomenclature used for animal iGluR LBDs has been maintained as reference (including the names loop 1 and loop 2 for the αA-αB and β2-αC loops, respectively). (A, Right) A 2D diagram of the secondary structure of the AtGLR3.3 LBD with the same color code for S1 and S2; cylinders, arrows, and lines represent α-helices, β-strands, and loops, respectively; blue stars indicate the positions of ligand-interacting residues; the position of the ATD and transmembrane domains in the topology of the protein is shown. (B–E) Close-up view of the ligand binding pocket in the crystal structures of the GLR3.3 LBD + l-Glu (B), + Gly (C), + l-Cys (D), and + l-Met (E). The 2|F|o − |F|c electron density omit maps contoured at 1.5 σ are shown for the ligand molecules (cyan sticks) and 2 additional water molecules of the Gly-bound structure (see SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A–D for the corresponding |F|o − |F|c omit maps). The residues or groups of atoms relevant for binding are indicated and represented as sticks, with nitrogen atoms in blue and oxygen atoms in red; protein carbon atoms are either green (if they belong to S1) or magenta (if they belong to S2). Hydrogen bonds are drawn as black dashes; not all interactions are shown for the sake of clarity. (F) Stereoview of the ligand binding site in a superposition of the AtGLR3.3 LBD structures from the 4 datasets. Domain 1 from each structure was superimposed. All side chains (lines) and main chains (tubes) surrounding the ligands are shown, except Tyr63 for clarity. The l-Glu–bound structure is blue, Gly is magenta, l-Cys is yellow, and l-Met is orange. One of the 2 resident water molecules of the pocket is shown; the 2 additional water molecules in the Gly-bound structure that are shown in C are not represented here for clarity.

In addition to these basic contacts, l-Glu, l-Cys, and l-Met share a weak CH–π interaction (38) between their Cβ-group (absent in Gly) and the aromatic Tyr63 ring, and additionally develop specific interactions as a consequence of their different side chains: l-Glu with Arg11 (salt bridge), Asn60 (hydrogen bond), and Gln129 (π-stacking); l-Cys with Arg11, Gln129, and Tyr180 (hydrogen bonds); and l-Met with Arg11 and Gln129 (hydrogen bonds). However, l-Cys and l-Met take advantage of a further binding contribution, as their sulfur atoms nestle in a series of sulfur–π interactions taking place between Met66, Tyr63, the ligand sulfur, and Tyr180 (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 A and B). The stabilization provided by such architecture gives a structural explanation for l-Cys and l-Met affinities, that are the strongest recorded in our binding assays (Fig. 1B and Table 1). Accommodation of a d-Glu molecule in the ligand site (by superposing its N-Cα-CO moiety on the same atoms of l-Glu) is expected to be strongly unfavorable, since its γ-carboxyl group would fall too close to the negatively charged side chains of Asp176 and Glu177, and possibly lose the salt link to Arg11. The network of hydrogen bonds/ionic interactions extends farther away from the ligand molecule, generating an intricate outer layer of connections (SI Appendix, Fig. S12C); however, a superposition of all our structures reveals a striking similarity in the orientation of the buried side chains in the region of the pocket, with the only variability confined to Val18 rotamers (Fig. 2F).

In principle, knowledge of the GLR3.3 LBD structure permits designing mutants incapable of binding any or some of the observed ligands, providing a tool for understanding the role of ligand binding in the generation of the downstream [Ca2+]cyt increase in root tip cells. As our complementation assays suggest that AtGLRs are functional when expressed in yeast (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) and given the reported successful expression of functional AtGLRs in HEK (19, 39) and COS-7 cells (14) and Xenopus oocytes (20), we anticipate that a eukaryotic system coexpressing selected full-length mutant GLRs and a Ca2+ sensor would be ideal to correlate specific LBD mutations to changes in Ca2+ conductance. On these bases, we generated a number of GLR3.3 LBD single or double mutants that were tested in Escherichia coli for their level of expression and solubility (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 and Table S2). All tested GLR3.3 LBD mutants did not retain sufficient solubility to be scaled up for larger production, with the exception of the S13A-Y14A double mutant, involving neighboring residues not directly in contact with the ligand (SI Appendix, Fig. S12C). For this double mutant, circular dichroism confirmed retention of the wild-type fold (SI Appendix, Fig. S9) but binding assays detected affinities for amino acid ligands comparable to the wild-type protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S14), suggesting that the identification of a binding-defective GLR3.3 LBD, through an in vitro approach, might not prove to be an easy task.

In conclusion, the X-ray crystal structures of the GLR3.3 LBD in complex with different ligands help rationalize the affinity data recorded (Fig. 1B and Table 1) and suggest plausible hypotheses for the differential ability of ligands to evoke [Ca2+]cyt transients (Discussion and SI Appendix, Figs. S2F and S3). Moreover, the crystal structure of a plant GLR LBD not only represents the crucial step along the way to engineer binding-defective receptors but is also a rational tool to 1) generate homology models of other Arabidopsis GLR isoforms and derive clues about their binding specificities, and 2) spotlight the peculiarities of GLRs from the plant kingdom through comparison with the known 3D structures of nonplant LBDs.

Homology Modeling of AtGLR Isoforms.

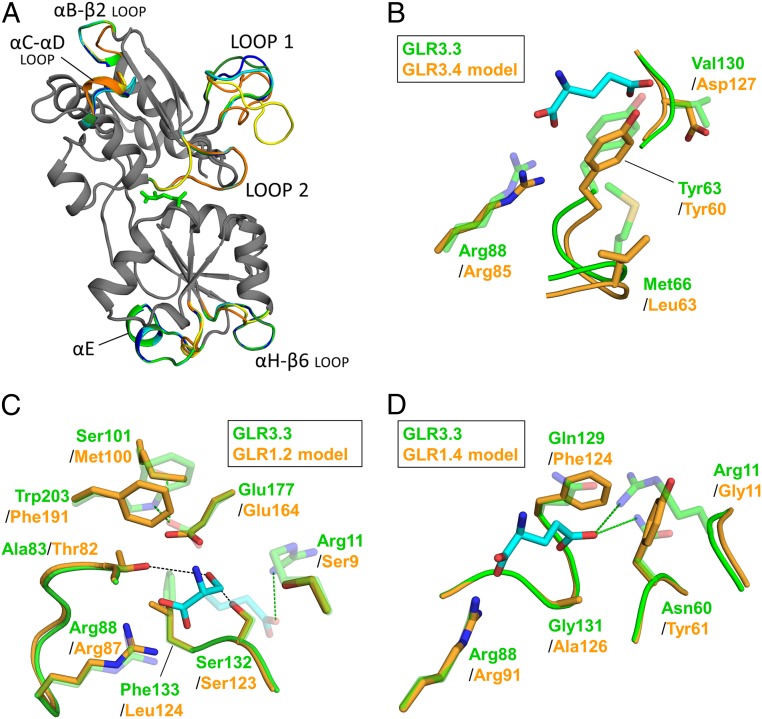

The availability of an experimental structure of an Arabidopsis GLR LBD prompted us to create and explore homology models of other AtGLR isoforms for which information about ligands is available in the literature [GLR1.2 (13), GLR1.4 (20), GLR3.1 and GLR3.5 (16), GLR3.4 (19)] (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Table S3). Inspection of the GLR3.3 LBD-based homology models generated (Fig. 3A) and of a sequence alignment of all 20 AtGLR isoform LBDs (SI Appendix, Fig. S15) shows that the highest structural variability clusters in solvent-exposed regions. We hypothesize that the variability of loop 2 might impact isoform substrate specificity, whereas differences in the αE-helix might influence intersubunit contacts (hence gating kinetics). In iGluRs, both substrate selectivity and gating kinetics have been shown to be finely regulated by intersubunit contacts (40, 41).

Fig. 3.

Homology modeling of other AtGLR isoforms. (A) Structural superposition of the GLR3.3 LBD structure (this work; green) with GLR3.3 LBD-based homology models of GLR1.2 (31% sequence identity; yellow), GLR1.4 (32%; orange), GLR3.1 (65%; cyan), GLR3.4 (62%; dark green), and GLR3.5 (60%; blue) LBDs, all in ribbon representations. The structurally coincident parts are shown in gray and only the divergent parts are colored. The l-Glu molecule in the GLR3.3 LBD structure is shown as green sticks. Note the absence of the αE-helix in the GLR1.2 and GLR1.4 models. UniProtKB primary accession numbers are GLR1.2 Q9LV72, GLR1.4 Q8LGN1, GLR3.1 Q7XJL2, GLR3.3 Q9C8E7, GLR3.4 Q8GXJ4, and GLR3.5 Q9SW97. (B) Model of the binding pocket of GLR3.4 (orange) superposed to the GLR3.3 LBD structure on which the model is based (transparent green). The l-Glu ligand of GLR3.3 is shown as cyan sticks. See SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for the numbering of GLR3.4. (C) Model of a d-Ser ligand molecule (cyan sticks) in the binding pocket of the GLR1.2 LBD homology model (orange), strictly reproducing the pose observed in PDB-deposited structures of d-Ser–containing LBDs (PDB ID codes 1pb8, 2rc8, 2rcb, 2v3u, and 4ykk). Relevant residues of the GLR1.2 LBD model (orange) and GLR3.3 LBD structure on which the model is based (transparent green) are shown. Relevant hydrogen bonds are represented as dashes (green for GLR3.3 LBD) and the position of a bound l-Glu molecule is indicated in transparency for reference. The Glu177 side chain in the GLR3.3 LBD is kept in place by 2 hydrogen bonds that are lost in the GLR1.2 LBD model. See SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for the numbering of GLR1.2. (D) Model of the binding pocket of GLR1.4 (orange) superposed to the GLR3.3 LBD structure on which the model is based (transparent green). The l-Glu ligand of GLR3.3 is shown as cyan sticks, with green dashes indicating relevant hydrogen bonds for GLR3.3. See SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for the numbering of GLR1.4.

Although homology modeling cannot equal experimental information from crystal structures, it helps identify, for a specific GLR isoform, which residues are likely to be relevant in the ligand binding site. These can be validated by comparisons made with the experimental information on ligand specificity. The GLR3.4 LBD model displays excellent quality statistics and its inspection is particularly interesting, considering that a set of ligands were tested on GLR3.4 homotetramers expressed in HEK cells (19). Despite the overall conservation of the ligand pocket, the binding of l-Glu might be less favored in GLR3.4 than in GLR3.3 due to the presence of a negative charge (Asp127 replacing GLR3.3 LBD Val130) at about 6 Å from the l-Glu ligand γ-carboxylate. Moreover, the presence of Leu63 in the GLR3.4 LBD in place of GLR3.3 Met66, and the subsequent shortening of the sequence of sulfur–π interactions described in our GLR3.3 structures, justifies the reported poor agonist effects of l-Cys and l-Ala on GLR3.4 channels (Fig. 3B) (19). Interesting hints are also provided by the study of models of LBDs from clade 1 isoforms. AtGLR1.2 is expressed in pollen; d-Ser and Gly (but not l-Glu) act as agonists in promoting GLR1.2-dependent pollen tube growth (13). Placing a molecule of d-Ser in the GLR1.2 LBD model ligand pocket, by superposing its N-Cα-CO moiety on that of the GLR3.3 ligand, indicates that few crucial residues might underlie the binding of d-Ser (Fig. 3C): Thr in place of Ala83 (conferring an additional hydrogen bond to the d-Ser hydroxyl group), Leu in place of Phe133 (creating room for the d-enantiomeric conformation), and the pair Met in place of Ser101 and Phe in place of Trp203 (releasing Glu177 hydrogen bonds, which would create room for the d-Ser side chain). Such a combination of residues is found in GLR1s only, thus suggesting that their occurrence might be a hallmark of the preference for the d-Ser ligand. The same modeling approach for AtGLR1.4 appears to justify the binding preference of this isoform for hydrophobic amino acids (Fig. 3D) (20).

Comparison of the GLR3.3 LBD Structure with Nonplant Homologous Structures.

Recent literature extends the evolutionary classification of A. thaliana clades to the whole plant kingdom, confirming the late appearance of clade 1 and 2 GLRs in flowering plants (6). Alignments of the GLR3.3 LBD sequence with LBDs of the other 19 AtGLR isoforms (SI Appendix, Fig. S15) and representative plant GLRs (SI Appendix, Fig. S16) indicate that sequence conservation across A. thaliana clades (∼30% between clades 1 and 3) is lower than intraclade conservation across different plant species (58 to 66% sequence identity within the clade 3 sequences of SI Appendix, Fig. S16). Therefore, we reckon that the GLR3.3 structure can be viewed as a representative of GLR3s of the whole plant kingdom in a cross-species comparison with nonplant homologs.

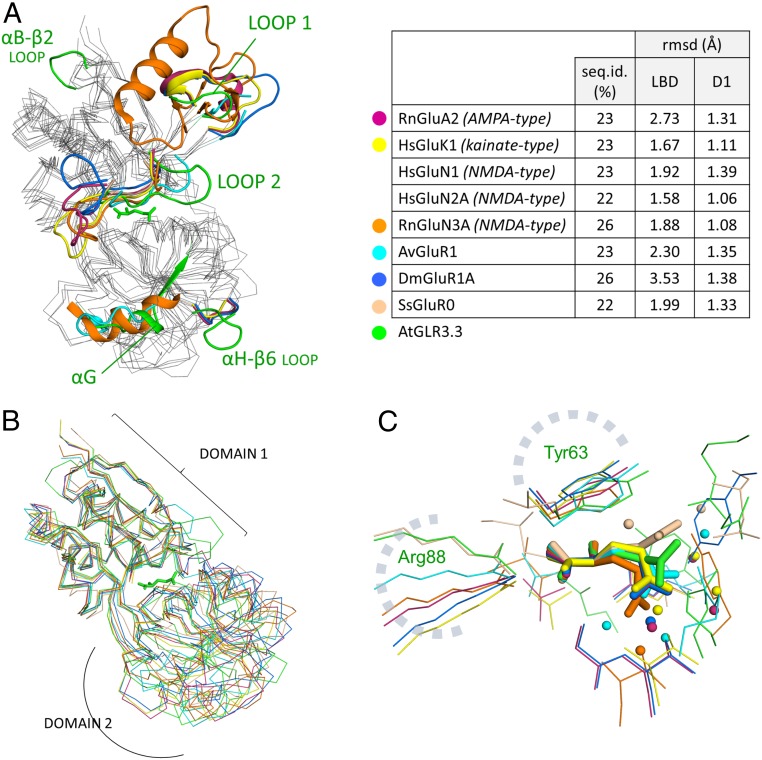

The Protein Data Bank hosts many iGluR/GLR LBDs from different species sharing a modest (20 to 25%) sequence identity, with a prevalence of the vertebrate LBDs of the 3 major types [α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA), kainate, and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)]. When a comparison of the GLR3.3 LBD structure with a range of representative LBDs (41–47) is run, an overall structural conservation, that is more pronounced in domain 1, is clearly evident (Fig. 4 A and B). However, in the secondary structure arrangement, plant GLR3s operate the peculiar evolutionary choices of 1) containing the expansion of loop 1 [whose enlargement in NMDA iGluRs affects intersubunit allostery (48)], 2) expanding the β1-αA and αH-β6 loops, and 3) drastically rearranging loop 2 (whose first part preceding the conserved Tyr63 is expanded and the second part—bulging outward in iGluRs—is deleted). Loops 2 and β1-αA host ligand-interacting side chains (Arg11, Asn60), whereas the αH-β6 loop is predicted to face the membrane. Interestingly, none of the above-mentioned structural features are predicted to be involved in intersubunit contacts.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the AtGLR3.3 LBD structure with nonplant homologous structures. (A) Overall superposition of the GLR3.3 LBD structure (+l-Glu; green) with X-ray structures of LBDs from rat AMPA-subtype GluA2 (RnGluA2; PDB ID code 1ftj; purple) (42), human kainate-subtype GluK1 (HsGluK1; PDB ID code 2zns; yellow) (43), rat NMDA-subtype GluN3A (RnGluN3A; PDB ID code 2rc7; orange) (41), rotifer AvGluR1 (PDB ID code 4io2; cyan) (44), fruit fly GluR1A (DmGluR1A; PDB ID code 5dt6; blue) (45), and cyanobacterial GluR0 (SsGluR0; PDB ID code 1ii5; pink) (46), with the GLR3.3 LBD l-Glu ligand shown as green sticks. The traits that are roughly structurally coincident are shown as gray wires connecting Cαs; only the parts that display relevant structural divergence from the other compared proteins are shown as colored ribbons. Note the large rearrangement of loop 2 in the GLR3.3 structure. (A, Right) For the same proteins, % sequence identities with the GLR3.3 LBD and Cα trace rmsd (Å) from the GLR3.3 LBD are given; for rmsd, values are provided for both the whole LBDs and domains 1 only and calculated excluding the protruding loop 1 that is highly variable in sequence and structure. (B) Least-squares superposition of the Cα traces of the AtGLR3.3 LBD structure (+l-Glu; green) with the crystallographic structures of LBDs from the same proteins shown in A (same color codes). This figure differs from A by the fact that the structures were superimposed by the domains 1 selectively (excluding the variable loops 1 and 2, not represented); the corresponding rmsd values are in the table in A. (C) Superposition of l-Glu ligand molecules (in stick representation) from different LBDs onto the l-Glu molecule of this study (AtGLR3.3; green): rat AMPA-subtype GluA2 (PDB ID code 1ftj; purple), human kainate-subtype GluK1 (PDB ID code 2zns; yellow), human NMDA-subtype GluN2A (PDB ID code 5h8f_A; orange) (47), rotifer AvGluR1 (PDB ID code 4io2; cyan), fruit fly GluR1A (PDB ID code 5dt6; blue), and cyanobacterial GluR0 (PDB ID code 1ii5; pink). Relevant side chains, main chains, and waters coordinating the ligands are shown. The highly conserved structural equivalents of GLR3.3 Tyr63 and Arg88 are indicated. The l-Glu molecules from rat GluA2 and fruit fly GluR1A almost perfectly overlap. Note that the coordination of the l-Glu ligand γ-carboxyl group is diversely achieved in different species.

Cross-species conservation of specific residues is spread throughout the amino acid sequence and mostly involves Gly or hydrophobic residues contributing to the structural core, including the conserved disulfide Cys189–Cys243 (absent in prokaryotic sequences and plant GLR1s only). In the binding site, the conserved architecture dictates the presence of a ligand-chelating Arg side chain (Arg88) projecting from helix αD, 1 acidic residue coordinating the α-amino group of the ligand (Glu177), and an aromatic side chain folding on the ligand Cβ (Tyr63) on loop 2 (Fig. 4C). In this area, the only plant-specific conserved residue is Asp81, that is placed at the center of a hydrogen-bond network keeping the protein domains together (SI Appendix, Fig. S12C).

Finally, we observe that the l-Glu ligand in the GLR3.3 LBD binding site maintains its χ1 dihedral angle in the range observed in vertebrate iGluRs (−73° to −83°) but extends the χ2 angle to −150° approaching the range observed in prokaryotic GLRs (−174° to −179°; −60° to −77° in iGluRs), thus locating its side chain halfway between the kinked conformation present in iGluRs and the fully extended conformation of prokaryotic GLRs (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S17).

Discussion

An increasing body of literature has provided evidence about the numerous physiological roles played by plant GLRs (49); however, several pieces of the puzzle are still missing, including the direct link between ligand binding and channel permeation. In this paper, we reconfirmed by using a combination of genetics and high-resolution optical microscopy the evidence of the primary role played by the GLR3.3 isoform in generating amino acid-evoked [Ca2+]cyt transients in the root tip cells of Arabidopsis seedlings. To gain a deeper view of its physiology, we biochemically reconstituted and characterized the GLR3.3 LBD in its binding properties and solved its crystal structure. We could thus redefine GLR3.3 as a broad-spectrum amino acid receptor and lay the bases for more precisely dissecting the determinants of plant GLR physiology.

The ranking of affinities determined by our GLR3.3 binding assays (Table 1) can be rationalized based on the reported crystal structures, since the increase in affinity from Gly to l-Glu to l-Met and l-Cys is explained by an increasing number of interactions with protein side chains. The amino acid-selective binding site is tuned for acceptance of different ligand residues, in line with previous speculations (18, 49) and in contrast to the selectivity profiles of prokaryotic and other eukaryotic GLRs, where a restricted preference for 1 or 2 l-amino acids is usually observed [l-Glu and l-Asp in Campylobacter (50); l-Glu in Nostoc (51, 52); l-Glu and l-Asp in rotifer Adineta (44); Gly in ctenophore Mnemiopsis (53); l-Glu in vertebrate AMPA-type and kainate-type iGluRs; Gly, l-Glu, and d-Ser in NMDA-type iGluRs (2)]. Only the prokaryotic GluR0 from Synechocystis displays a similar multiple binding profile for l-amino acids, with l-Glu and l-Gln as the strongest binders and l-Ser, l-Ala, l-Thr, and Gly as significantly weaker (54). Our affinity values for GLR3.3 (in the submicromolar to micromolar range) (Table 1) are in line with the ligand concentrations of our in vivo experiments (Fig. 1C) and with the values obtained for the animal receptor homologs, through the same or different techniques [around 400 to 800 nM (42, 55–57)].

Interestingly, the LBD of the AvGluR1 receptor from the rotifer A. vaga is the only LBD for which crystal structures are available in complex with a set of amino acid ligands (l-Glu, l-Asp, l-Ser, l-Ala, l-Met, l-Phe) (44); in this receptor, binding of l-Ser, l-Ala, and l-Met is mediated by a chloride ion coordinated by 1/2 Arg side chains in a position not far from GLR3.3 Arg11. Instead, our crystallographic refinement excluded the presence of ions in the GLR3.3 binding pocket (SI Appendix, Fig. S18); moreover, unlike what is observed in AvGluR1 and animal iGluRs, there are no ordered water molecules in direct contact with the l-Glu ligand (Fig. 4C) and no contributions from protein main-chain atoms in the recognition of the ligand side chains. It is worth noticing that in the binding site of animal GLRs, all protein residues interacting with the l-Glu ligand side chain belong to domain 2, with the only exception of the conserved equivalent of Tyr63; this suggests that the peculiar expansion of domain 1 loops (loops 2 and β1-αA) observed in GLR3.3 is likely instrumental in broadening substrate specificity.

One issue that remains unsolved is that the second highest in vitro affinity observed for GLR3.3 LBD (l-Met; Table 1) does not correlate with the poor capacity of the same ligand to evoke [Ca2+]cyt increases in root tips (SI Appendix, Figs. S2F and S3). This suggests that a simplistic affinity–conductance correlation is true for most but not all ligands, and additional layers of complexity come into play between receptor binding and change in Ca2+ conductance. In iGluRs, the early assumption that the extent of the agonist-induced LBD closure correlates with its efficacy (42, 58) was substantially confirmed in full-length structures (59). Conversely, in the GLR3.3 structures, like in AvGluR1 (44), the extent of the LBD clamshell closure is the same for all ligands, despite their different affinities (Table 1) and their different abilities to evoke cytosolic Ca2+ increases in root tip cells (SI Appendix, Figs. S2F and S3). Therefore, the discrepancy between l-Met affinity and its in vivo effect depends on factors that are not immediately evident from the X-ray structures. One possible explanation is that the in planta subunit composition of the tetrameric channel might modulate the affinity for specific ligands, as previously observed for animal iGluRs (40, 41). Future research is indeed needed to shed light on this important aspect.

In light of these considerations, homology models of other GLR isoforms based on our structures might prove helpful to gain a clear picture of the GLR response; they confirm ligand selectivity data reported in the literature and predict mutations that impact on ligand binding. Our GLR3.4 model fairly explains why l-Cys and l-Glu are not the best amino acidic agonists of this isoform, but only binding assays on a reconstituted GLR3.4 LBD would permit specific affinity comparisons between GLR3.3 and 3.4 regarding their common preference for l-Asn, l-Ser, and Gly (19). Our GLR1.2 model posits the response to d-Ser as a feature acquired by clade 1 GLRs; accordingly, our assays on GLR3.3 detected a low affinity for d-Ser (Table 1); however, we cannot exclude that affinity for d-Ser might be additionally finely tuned by residues away from the binding site, as it has been shown for vertebrate delta and NMDA receptors (41, 60). The preference of GLR1.4 for amino acid ligands with bulky hydrophobic side chains (l-Met, l-Trp, l-Phe, l-Leu, l-Tyr) (20) is precisely rationalized by our GLR1.4 model that predicts a hydrophobic environment surrounding the amino acid ligand side chain (Fig. 3D). Instead, due to high sequence conservation, the binding pockets in our models of GLR3.1 and GLR3.5 [reported to be specifically activated by l-Met for the regulation of stomatal aperture (16)] are remarkably similar to that of GLR3.3. Actually, both automatically generated homology models publicly available in the SWISS-MODEL Repository (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/repository) (61) and previous AtGLR LBD models presented in the literature (8, 16, 20) suffer from problematic alignment with the selected template (generally rat iGluR LBD) and present significant deviations from the experimental structure we present.

In conclusion, this study confirms the involvement of GLR3.3 in amino acid response in A. thaliana root tip cells, supporting its role as a ligand-gated Ca2+ channel. Moreover, we present the biochemical and structural characterization of its ligand-binding domain, showing that it works as an amino acid receptor with distinct specificity. Such structural knowledge that adds to the collection of bacterial and animal LBD structures available on one hand provides a perspective view on the evolution of these ancestral proteins along the plant lineage and, on the other, represents a working tool to engineer all plant GLR isoforms aiming at a deeper understanding of their basic physiology.

Materials and Methods

A. thaliana WT, glr3.3-1, and glr3.3-2 plants were in the Col-0 background. Growth conditions, generation of transgenic lines, yeast complementation test, measurement of Ca2+ dynamics, description of biochemical and structural methodological assays, statistical and computational methods, protocols used for localization and expression pattern studies, and other imaging measurements are reported in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Data Availability.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6R85, 6R88, 6R89, and 6R8A for the complexes of GLR3.3 LBD with l-Glu, Gly, l-Cys, and l-Met, respectively). Raw data obtained from imaging experiments and binding assays are available upon request.

Accession Numbers.

Sequence data for GLR3.3 (AT1G42540) can be found in the Arabidopsis Araport (https://www.araport.org/) or TAIR (https://www.Arabidopsis.org/) databases. The corresponding GLR3.3 amino acid sequence is UniProtKB Q9C8E7 (UniProt database; https://www.uniprot.org/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The glr3.3-1 and glr3.3-2 T-DNA mutant lines were kindly provided by Prof. Zhi Qi (College of Life Sciences, Inner Mongolia University). The vector harboring the GLR3.3 coding sequence was kindly provided by Prof. Josè Feijo and Dr. Michael Wudick (Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland). GLR3.3pro:GLR3.3-EGFP seeds were kindly provided by Prof. Edgar Spalding (Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin). We thank Dr. Antonio Chaves Sanjuán (Department of Biosciences, University of Milan) for helpful discussions and Dr. Delia Tarantino (Department of Biosciences, University of Milan) for help with the microscale thermophoresis analysis. Sadly, Delia passed away on August 14; we are grateful to her for her endless support and friendliness. Part of this work was carried out at NOLIMITS, an advanced imaging facility established by the University of Milan. This work was supported by Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base 2010 RBFR10S1LJ_001 Grant (to A. Costa), PIANO DI SVILUPPO DI ATENEO 2017 (University of Milan) (A. Costa), a postdoctoral fellowship from the Department of Biosciences (University of Milan) (to A.A.), a PhD fellowship from the University of Milan (to F.G.D.), a postdoctoral fellowship from the European Commission within the framework of the SUSTAIN-T Project of the Erasmus Mundus Programme, Action 2—STRAND 1, Lot 7, Latin America (to N.R.A.), and Laserlab Europe (EU-H2020 654148) (to A. Bassi). We acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities (Proposal MX1894) and the staff of beamline ID29 for in situ assistance, and the Diamond Light Source (Didcot, UK) for synchrotron beamtime (Proposal MX20221) and the staff of beamline I04 for assistance with remote data collection.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, http://www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6R85, 6R88, 6R89, and 6R8A for the complexes of the GLR3.3 LBD with l-Glu, Gly, l-Cys, and l-Met, respectively).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1905142117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chiu J., DeSalle R., Lam H. M., Meisel L., Coruzzi G., Molecular evolution of glutamate receptors: A primitive signaling mechanism that existed before plants and animals diverged. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 826–838 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traynelis S. F., et al. , Glutamate receptor ion channels: Structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 405–496 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wudick M. M., Michard E., Oliveira Nunes C., Feijó J. A., Comparing plant and animal glutamate receptors: Common traits but different fates? J. Exp. Bot. 69, 4151–4163 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acher F. C., Bertrand H. O., Amino acid recognition by Venus flytrap domains is encoded in an 8-residue motif. Biopolymers 80, 357–366 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davenport R., Glutamate receptors in plants. Ann. Bot. 90, 549–557 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bortoli S., Teardo E., Szabò I., Morosinotto T., Alboresi A., Evolutionary insight into the ionotropic glutamate receptor superfamily of photosynthetic organisms. Biophys. Chem. 218, 14–26 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S. K., Chien C. T., Chang I. F., The Arabidopsis glutamate receptor-like gene GLR3.6 controls root development by repressing the Kip-related protein gene KRP4. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 1853–1869 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubos C., Huggins D., Grant G. H., Knight M. R., Campbell M. M., A role for glycine in the gating of plant NMDA-like receptors. Plant J. 35, 800–810 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng Y., Zhang X., Sun T., Tian Q., Zhang W. H., Glutamate receptor Homolog3.4 is involved in regulation of seed germination under salt stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 59, 978–988 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mousavi S. A. R., Chauvin A., Pascaud F., Kellenberger S., Farmer E. E., GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE genes mediate leaf-to-leaf wound signalling. Nature 500, 422–426 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyota M., et al. , Glutamate triggers long-distance, calcium-based plant defense signaling. Science 361, 1112–1115 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen C. T., Kurenda A., Stolz S., Chételat A., Farmer E. E., Identification of cell populations necessary for leaf-to-leaf electrical signaling in a wounded plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 10178–10183 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michard E., et al. , Glutamate receptor-like genes form Ca2+ channels in pollen tubes and are regulated by pistil D-serine. Science 332, 434–437 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wudick M. M., et al. , CORNICHON sorting and regulation of GLR channels underlie pollen tube Ca2+ homeostasis. Science 360, 533–536 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho D., et al. , De-regulated expression of the plant glutamate receptor homolog AtGLR3.1 impairs long-term Ca2+-programmed stomatal closure. Plant J. 58, 437–449 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong D., et al. , L-Met activates Arabidopsis GLR Ca2+ channels upstream of ROS production and regulates stomatal movement. Cell Rep. 17, 2553–2561 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi Z., Stephens N. R., Spalding E. P., Calcium entry mediated by GLR3.3, an Arabidopsis glutamate receptor with a broad agonist profile. Plant Physiol. 142, 963–971 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens N. R., Qi Z., Spalding E. P., Glutamate receptor subtypes evidenced by differences in desensitization and dependence on the GLR3.3 and GLR3.4 genes. Plant Physiol. 146, 529–538 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincill E. D., Bieck A. M., Spalding E. P., Ca2+ conduction by an amino acid-gated ion channel related to glutamate receptors. Plant Physiol. 159, 40–46 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tapken D., et al. , A plant homolog of animal glutamate receptors is an ion channel gated by multiple hydrophobic amino acids. Sci. Signal. 6, ra47 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F., et al. , Glutamate receptor-like channel3.3 is involved in mediating glutathione-triggered cytosolic calcium transients, transcriptional changes, and innate immunity responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 162, 1497–1509 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida R., et al. , Glutamate functions in stomatal closure in Arabidopsis and fava bean. J. Plant Res. 129, 39–49 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar J., Mayer M. L., Functional insights from glutamate receptor ion channel structures. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 75, 313–337 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer M. L., The challenge of interpreting glutamate-receptor ion-channel structures. Biophys. J. 113, 2143–2151 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greger I. H., Watson J. F., Cull-Candy S. G., Structural and functional architecture of AMPA-type glutamate receptors and their auxiliary proteins. Neuron 94, 713–730 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen K. B., et al. , Structure, function, and allosteric modulation of NMDA receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 150, 1081–1105 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu S., Gouaux E., Structure and symmetry inform gating principles of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 112, 11–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behera S., et al. , Analyses of Ca2+ dynamics using a ubiquitin-10 promoter-driven Yellow Cameleon 3.6 indicator reveal reliable transgene expression and differences in cytoplasmic Ca2+ responses in Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa) roots. New Phytol. 206, 751–760 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krebs M., et al. , FRET-based genetically encoded sensors allow high-resolution live cell imaging of Ca2+ dynamics. Plant J. 69, 181–192 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa A., Candeo A., Fieramonti L., Valentini G., Bassi A., Calcium dynamics in root cells of Arabidopsis thaliana visualized with selective plane illumination microscopy. PLoS One 8, e75646 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Candeo A., Doccula F. G., Valentini G., Bassi A., Costa A., Light sheet fluorescence microscopy quantifies calcium oscillations in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 1161–1172 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madden D. R., The structure and function of glutamate receptor ion channels. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 91–101 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jerabek-Willemsen M., et al. , MicroScale thermophoresis: Interaction analysis and beyond. J. Mol. Struct. 1077, 101–113 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuermann J. P., Tanner J. J., MRSAD: Using anomalous dispersion from S atoms collected at Cu Kalpha wavelength in molecular-replacement structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 1731–1736 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panjikar S., Parthasarathy V., Lamzin V. S., Weiss M. S., Tucker P. A., On the combination of molecular replacement and single-wavelength anomalous diffraction phasing for automated structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1089–1097 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holm L., Laakso L. M., Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W351–W355 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian W., Chen C., Lei X., Zhao J., Liang J., CASTp 3.0: Computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W363–W367 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishio M., Umezawa Y., Fantini J., Weiss M. S., Chakrabarti P., CH-π hydrogen bonds in biological macromolecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 12648–12683 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vincill E. D., Clarin A. E., Molenda J. N., Spalding E. P., Interacting glutamate receptor-like proteins in phloem regulate lateral root initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 1304–1313 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furukawa H., Singh S. K., Mancusso R., Gouaux E., Subunit arrangement and function in NMDA receptors. Nature 438, 185–192 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Y., Harrison C. B., Freddolino P. L., Schulten K., Mayer M. L., Molecular mechanism of ligand recognition by NR3 subtype glutamate receptors. EMBO J. 27, 2158–2170 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong N., Gouaux E., Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor: Crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron 28, 165–181 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unno M., et al. , Binding and selectivity of the marine toxin neodysiherbaine A and its synthetic analogues to GluK1 and GluK2 kainate receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 413, 667–683 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lomash S., Chittori S., Brown P., Mayer M. L., Anions mediate ligand binding in Adineta vaga glutamate receptor ion channels. Structure 21, 414–425 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y., et al. , Novel functional properties of Drosophila CNS glutamate receptors. Neuron 92, 1036–1048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer M. L., Olson R., Gouaux E., Mechanisms for ligand binding to GluR0 ion channels: Crystal structures of the glutamate and serine complexes and a closed apo state. J. Mol. Biol. 311, 815–836 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hackos D. H., et al. , Positive allosteric modulators of GluN2A-containing NMDARs with distinct modes of action and impacts on circuit function. Neuron 89, 983–999 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Regalado M. P., Villarroel A., Lerma J., Intersubunit cooperativity in the NMDA receptor. Neuron 32, 1085–1096 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forde B. G., Roberts M. R., Glutamate receptor-like channels in plants: A role as amino acid sensors in plant defence? F1000Prime Rep. 6, 37 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Müller A., et al. , A bacterial virulence factor with a dual role as an adhesin and a solute-binding protein: The crystal structure at 1.5 Å resolution of the PEB1a protein from the food-borne human pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 160–171 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J. H., et al. , Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the GluR0 ligand-binding core from Nostoc punctiforme. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61, 1020–1022 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee J. H., et al. , Crystal structure of the GluR0 ligand-binding core from Nostoc punctiforme in complex with L-glutamate: Structural dissection of the ligand interaction and subunit interface. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 308–316 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alberstein R., Grey R., Zimmet A., Simmons D. K., Mayer M. L., Glycine activated ion channel subunits encoded by ctenophore glutamate receptor genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E6048–E6057 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen G. Q., Cui C., Mayer M. L., Gouaux E., Functional characterization of a potassium-selective prokaryotic glutamate receptor. Nature 402, 817–821 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seidel S. A. I., et al. , Label-free microscale thermophoresis discriminates sites and affinity of protein-ligand binding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 10656–10659 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuusinen A., Arvola M., Keinänen K., Molecular dissection of the agonist binding site of an AMPA receptor. EMBO J. 14, 6327–6332 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen G. Q., Gouaux E., Overexpression of a glutamate receptor (GluR2) ligand binding domain in Escherichia coli: Application of a novel protein folding screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13431–13436 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin R., Banke T. G., Mayer M. L., Traynelis S. F., Gouaux E., Structural basis for partial agonist action at ionotropic glutamate receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 803–810 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dürr K. L., et al. , Structure and dynamics of AMPA receptor GluA2 in resting, pre-open, and desensitized states. Cell 158, 778–792 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tapken D., et al. , The low binding affinity of D-serine at the ionotropic glutamate receptor GluD2 can be attributed to the hinge region. Sci. Rep. 7, 46145 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bienert S., et al. , The SWISS-MODEL Repository—New features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D313–D319 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6R85, 6R88, 6R89, and 6R8A for the complexes of GLR3.3 LBD with l-Glu, Gly, l-Cys, and l-Met, respectively). Raw data obtained from imaging experiments and binding assays are available upon request.