Abstract

Aims

Patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) are a distinctive method of evaluating patient response to health care or treatment. This systematic review aimed to analyse the impact of PROs in patients on direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) treatment, prescribed for any indication (e.g. venous thromboembolism treatment or atrial fibrillation) using controlled trials (CT) and real‐world observational studies (OS).

Methods

A systematic search of articles was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines using databases, with the last update in November 2018. The Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing bias in randomized CTs and the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale adapted for cross‐sectional studies were used. Outcomes evaluated were related to health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), satisfaction, adherence and compliance.

Results

Twenty‐one original studies (6 CT, 15 OS) were included. HRQoL was assessed by 6 (1 CT, 5 OS) studies and reported that HRQoL scores were similar in patients on DOACs and warfarin. Patients prescribed DOACs presented higher HRQoL scores which were attributed to lack of intense monitoring required compared with warfarin but this was not statistically significant. The majority of studies (5 CT, 9 OS) investigated patient‐reported satisfaction, indicating greater satisfaction with DOACs with significantly lower burden and increased benefit scores for patients on DOACs. Patient‐reported expectations, compliance and adherence were similar for patients on DOACs and warfarin.

Conclusion

Patients appear to prefer treatment with DOACs vs warfarin. This is shown by the higher quality of life, satisfaction and adherence described in the studies. However, heterogeneity in the analysed studies does not allow firm conclusions.

Keywords: direct‐acting oral anticoagulants, patient‐reported outcomes, systematic review, warfarin

What is already known about this subject

Direct oral anticoagulants have revolutionized treatment of venous thromboembolism and prevention of stroke due to atrial fibrillation with demonstrated similar efficacy and safety as warfarin.

Patient‐reported outcomes are an optimum method of evaluating patients' perceptions of these agents.

What this study adds

Patients report higher satisfaction, adherence and enhanced quality of life with direct oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin, indicating a higher preference for these agents.

1. INTRODUCTION

Inception of new (or direct) oral anticoagulants (NOACs or DOACs) have bought a new dawn to the treatment of thromboembolic conditions such as nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) and treatment or prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism (VTE: deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism). These direct oral anticoagulants (e.g. apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran and edoxaban) have made rapid progress in revolutionising anticoagulation and have been extensively investigated and researched in clinical trials for their clinical effectiveness and safety profile in comparison with standard treatment.1

Anticoagulation with warfarin, a potent vitamin K antagonist (VKA), has been the mainstay of treatment for prophylaxis, treatment and long‐term management of thromboembolic conditions such as VTE, AF and stroke. Use of warfarin effectively is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of stroke and mortality associated with AF.1 However, warfarin use is limited by its narrow therapeutic index requiring regular monitoring of international normalized ratio (INR), multiple drug interactions and dietary restrictions.2 Over the past decade, the introduction of DOAC has revolutionized the treatment of these conditions without the complications associated with warfarin. DOACs have also been recognized as a safe and effective treatment option in thromboprophylaxis post orthopaedic surgery. However, these agents have been known to carry a potential risk of bleeding with no actual method of anticoagulation reversal.3, 4

DOACs have been credited with reducing complications that arise through monitoring and individual‐dosing of VKAs. Dabigatran was first approved for use in the UK for AF and VTE in 2011 following results of the RELY trial.5 Rivaroxaban approval followed showing noninferiority to warfarin for the prevention of AF and VTE in the ROCKET AF study in 2011.6 The ARISTOTLE trial led to the licensing of apixaban in 2012 showing that apixaban was superior to warfarin in preventing stroke in AF patients and VTE.7 Edoxaban was approved in 2015 after the result of the ENGAGE‐AF trial displaying noninferiority of edoxaban to warfarin.8 These clinical studies emphasized the clinical efficacy of the DOACs vs warfarin with the enhanced benefit of reduced intracranial and major bleeding, but showed a higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Nevertheless, the European Society of Cardiology and NICE have recommended DOACs as a suitable option for nonvalvular AF over warfarin.9, 10

Patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) are testimonies from the patient about how they feel about any particular condition or treatment they are receiving without any intervention or bias from the clinicians.11 PROs include any evaluation of treatment or outcome directly from patient interviews, questionnaires or specifically developed tools to capture and enable analysis of valuable patient‐reported data. PROs provide valuable data from the patient's perspective and are sometimes used as primary outcomes from clinical trials. However, more often, PROs are conveyed as subanalyses after the initial trials have been published.12

PROs are subjective measures relating to patent experience and quantify assessment of patient satisfaction, adherence or health‐related quality of life (HRQoL).13 HRQoL can be defined as an evaluation of impairment, disability or handicap.12, 14 Patient satisfaction determines perceived burden or benefits of the perceived treatment being appraised.12

The Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS), Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) and Perception of Anticoagulation Questionnaire (PACT) are tools used to assess satisfaction.15, 16, 17 The Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale has been specifically developed to measure both satisfaction and HRQoL.18, 19 Patient‐reported adherence can be evaluated using self‐report scales such as the Morisky 4‐ or 8‐item adherence scale.20 These tools measure disease or treatment‐specific objectives describing severity of symptoms, benefit, adverse drug effects in order to capture the patients' well‐being and experience with the intervention. Such tools have been developed to measure PROs in patients receiving anticoagulation and have been scrutinized and validated prior to use.

A recent systematic review by Generalova et al. explored clinicians' views and experiences of DOACs in patients with AF presenting evidence of clinician preference in recommending DOACs as first choice for these patients.21 However, publishing/reporting of PROs from clinical trials have been limited and to date there are no systematic reviews conducted that evaluate or cumulatively analyse the results of PROs in patients prescribed DOACs. This systematic review aims to bridge this gap in knowledge and enhance understanding of PROs in anticoagulation with DOACs. The aim of the current review is to systematically assess the PROs reported by adults receiving DOACs, with additional focus on patient satisfaction, adherence, compliance and HRQoL using original studies (controlled trials and observational real‐world studies).

2. METHODS

2.1. Scope of review: Eligibility criteria

The systematic review process was conducted following PRISMA guidelines.22 The primary investigator (S.K.A.) applied the eligibility criteria to examine abstracts of original journal articles published in English where (i) PROs and (ii) DOACs, namely apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran or edoxaban, were included. Finally, abstracts had to report PROs based on a recognized PRO tool with measurable outcomes. The following types of studies were excluded: review articles, observational studies and articles on compliance or persistence that focussed on tablet count or prescription monitoring.

For population attributes, studies that were included that assessed PROs in adults being treated with a DOAC. The search was restricted to studies involving humans and original journal articles. Titles and abstracts were screened to remove studies that were irrelevant to the aim of the review and full texts of the remaining studies that analysed the required data but did not use a recognized PRO tool were excluded.

2.2. Information sources

The following databases were searched between September 2018 and October 2018 with no filters set on publication date: PubMed (United States National Library of Medicine), Cumulative index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL—Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands), MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online, or MEDLARS Online), Embase (Excerpta Medica database) from 1974 to September 2018, SCOPUS and Springer Link databases. Google Scholar was also searched to identify articles not indexed in scientific databases. References cited in the reference list of each identified original research were scanned for any additional articles that would be relevant to this review; these were subsequently also scanned for reviews and studies that may have been relevant and which were subject to the same eligibility evaluation.

2.3. Searching

The search strategy identified original research on patient‐reported outcomes associated with the use of new or direct oral anticoagulants. Search terms were constructed using a population–intervention–outcome model and considered the following strategy limited to “adults (limit: 18+ years), humans and English language”. Search terms were: anticoagulant* OR oral anticoagulant* OR novel oral anticoagulant* OR non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant* (NOAC) OR vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant* OR coumarin* OR dabigatran OR rivaroxaban OR apixaban OR edoxaban OR warfarin OR direct factor Xa inhibitor* OR direct thrombin inhibitor* AND patient‐reported outcomes OR patient‐reported satisfaction OR patient‐reported adherence OR quality of life.

2.4. Study selection

After possible studies were identified, all retrieved titles were screened by the primary investigator (S.K.A.) to determine their potential relevance. The assessed abstracts were independently by another investigator (S.S.H.) against 5 inclusion criteria: (i) original research studies; (ii) recognized and validated tool to measure PROs; (iii) patients were taking a DOAC for >4 weeks; (iv) adult subjects (age ≥19 years); and (v) reported in English. Full papers from potential studies were independently assessed by the investigators (S.K.A. and S.S.H.).

2.5. Data collection process

All studies selected for this systematic review were screened by 2 reviewers independently to validate the results. The purpose, study design, number of participants, description of observations and outcome measures were recorded. The data from all the retrieved studies were subsequently collected and tabulated using a form developed by the lead author that was verified by the second reviewer. Extracted information from studies is mentioned in Table 1. The extracted information included study design, study participants and settings, objectives of the study, response rate and sample size, outcomes measured, summarized results and main findings of the study.

Table 1.

Summary of controlled trials and observational studies

| Author, y of publicationref | Data collection period | Treatment/population | Study details | PRO assessment | Sample size | Outcomes measured | Main findings of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with atrial fibrillation | |||||||

| Monz et al. 201323 | December 2005–December 2007 |

Treatment: Dabigatran vs dose adjusted warfarin population: For nonvalvular AF Mean age: 71.5 y Female: 36.4% |

Design: RCT Subgroup of RE‐LY population RE‐LY = prospective, randomized open‐label, blinded end‐point evaluation Setting: 44 countries and 951 clinical centres |

Patient‐reported HRQoL using EQ‐5D utility and visual analogue scale scores, assessed at baseline, 3 and 12 months | 1435 patients (497 in dabigatran 110 mg BD, 485 dabigatran 150 mg BD group and 453 warfarin group) | Changes in HRQoL over time 5 questions on 5 dimensions of health (mobility, self‐care, usual; activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) and 3 levels of response |

HRQoL: No statistically significant difference between dabigatran groups or warfarin groups. Utility weighted scores for dabigatran 150 mg BD ranged from 0.805 to 0.811 for dabigatran 110 mg BD and did not change over the 1‐y observation period. No difference between dabigatran and warfarin group except dabigatran 150 mg at 3 months. None of the in‐groups or between‐group analyses were significant |

| Hohnloser et al. 201524 | October 2012–September 2013 |

Treatment: Rivaroxaban vs standard therapy for cardioversion Population: Patients with AF requiring cardioversion Age range: 18–65 y Female: 52.7% |

Design: RCT post hoc study of X‐VERT trial, Setting: 7 countries USA, UK Canada, Netherlands, France, Germany and Italy |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction using user TSQM Ver II, completed after 42 days of treatment | 705 patients completed the questionnaire |

11 items, 4 subscales Convenience, effectiveness, global satisfaction and side effects based on Likert scales |

Satisfaction: Rivaroxaban group reported increased score for convenience (81.74 vs 65.78), effectiveness (39.41 vs 32.95) and global satisfaction (82.07 vs 66.74), P < .0001. |

| Coleman et al. 201625 |

Treatment: Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention Population: Patients with nonvalvular AF prescribed rivaroxaban Mean age: 71 y Female: 36.3% |

Design: Nonrandomized controlled trial Xantus ACTS substudy Prospective international noninterventional phase 4 study, Setting: 308 investigational sites in 21 countries |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction using ACTS implemented at baseline and 3 months after switch | 1291 patients with prior warfarin treatment switched to rivaroxaban | 12‐item burden scale (max 60 points) and 3‐item benefits scale (max 15 points) |

Satisfaction: Baseline ACTS burden and benefit scores 50.51 and 10.30 respectively, scores improved after 3 months to 54.5 and 11.4, respectively |

|

| Koretsune et al. 201726 | September 2015–October 2016 |

Treatment: Patients switched from warfarin to apixaban population: Patients with nonvalvular AF Mean age: 76 y Female: 37.9% |

Design: RCT prospective short‐term multicentre single‐arm observational study AGAIN study Setting: 149 institutions in Japan |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction using ACTS, implemented before switch and after 12 weeks of treatment with apixaban | 697 patients switched to apixaban | 12‐item burden scale (max 60 points) and 3‐item benefits scale (max 15 points) | Satisfaction: No significant changes in ACTS benefit scores (10.5 vs 10.4) but significant changes in ACTS burden scores vs baseline (55.6 vs 49.7, P < .0001) |

| Alegret et al., 201427 | 1 February–30 June 2012 |

Treatment: On VKA or NOAC Population: Patients with AF undergoing electrical cardioversion Mean age: 62 y Female: 19% |

Design: Prospective study Patients included in the CARDIOVERSE study Setting: Conducted in 67 hospitals in Spain |

Patient‐reported HRQoL in patients on oral anticoagulants using Sawicki questionnaire, assessed at baseline and 6 months |

416 patients: 351 in VKA group and 65 in DOAC (59 on dabigatran and 5 on rivaroxaban) group. At 6 months 215 in VKA group and 37 in NOAC group completed the questionnaire |

32 items grouped in 5 dimensions. Patients score on scale of 1–6 to determine their treatment related quality of life | HRQoL: No significant differences seen at baseline between the groups. At baseline, general treatment satisfaction score was significantly lower in the NOAC group (better HRQoL). Global score was also lower, indicating better HRQoL in NOAC group (10.3 vs 9.6). No significant differences seen at 6 months between the groups. |

| Hanon et al., 201628 | April 2013–June 2014 |

Treatment: Patients previously treated with warfarin and switched to rivaroxaban Population: Nonvalvular AF patients Mean age: 74.8 y Female: 37% |

Design: Prospective, observational study Setting: French multicentre |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction using ACTS, administered at baseline, 1, 3 and 6 months | 405 patients switched to rivaroxaban | A validated 15‐item patient‐reported scale including 12‐item ACTS burdens scale and 3 item ACTS benefits scale | Satisfaction: At 3 months, statistically significant patient satisfaction with rivaroxaban compared with VKA warfarin. Mean ACTS burden score (46.5 vs 54.9, P < .001) and benefit scale (10.4 vs 10.9, P < .001) between rivaroxaban and VKA |

| Marquez‐Contreras et al. 201629 | May 2013–April 2015 |

Treatment: Patients on rivaroxaban Population: Patients with nonvalvular AF Mean age: 75 y Female: 50.3% |

Design: Observational, prospective, multicentre, longitudinal study Setting: Conducted in 160 primary and specialty care centres in Spain |

Patient‐reported quality of life using Sawicki questionnaire, administered at baseline and at 6 and 12 months | 370 included in the study | Sawicki questionnaire = 32 items grouped in 5 dimensions. General treatment satisfaction, self‐efficacy, strained social network, daily hassles and distress | HRQoL: Global compliance was 84.1% and 80.3% at 6 and 12 months respectively. Average QoL rating was 112.85 in noncompliant and 111.80 in the compliant group (p > 0.05). After 12 months 124.67 in noncompliant group and 83.47 in the compliant group (P < .0001) showing a significantly improved QoL. |

| Keita et al., 201730 | July 2014 to July 2015 |

Treatment: Patients prescribed warfarin or switched to DOAC or initiated on DOAC treatment Population: VTE patients Mean age: 60.4 y Female: 46% |

Design: Observational descriptive study Setting: multicentre in France |

Patient‐reported adherence, satisfaction and QoL using Morisky medication adherence scale, MMAS‐8, EQ‐5D, perception of anticoagulation questionnaire part 2, administered after 3 months treatment and 6 months treatment | 100 patients 50 in warfarin group and 50 in DOAC group | EQ‐5D questionnaire (5 dimensions, mobility, autonomy, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) with 3 response levels. PACT‐Q2 to assess treatment satisfaction: 3 domains, practical aspects satisfactions and adherence. MMAS‐8: 8‐item questionnaire |

HRQoL: VKA patients reported more negative experience than DOAC group in EQ‐5d questionnaire. No significant difference in overall quality of life in favour of DOAC group (71 vs 65, P < .063). Satisfaction: Satisfaction with PACT‐Q2: >90% of patients were satisfied with their VKA or DOAC treatment. Adherence: Adherence with MMAS‐8 7.2 in VKA group vs 7.7 in DOAC group greater adherence in DOAC group especially after 6 months treatment. |

| Contreras Muruaga et al. 201731 | September 2014–March 2015 |

Treatment: Population: Patients with nonvalvular AF Mean age: 75 y Female: 44.2% |

Design: Observational cross‐sectional study Setting: 63 neurology departments in Spain |

Patient‐reported satisfaction, QoL and perceptions of VKA vs DOACs (only QoL included) |

1337 patients: 587 on DOAC, 750 on VKA |

EQ‐5D 3‐level questionnaire and visual acuity score |

HRQoL: Mean EQ‐5D 3 L score was 75.9 Patients taking VKA with longer time in therapeutic range were more satisfied. DOAC = 76.26, VKA = 75.05: Showing no significant difference in HRQoL. HRQoL for all 3 DOACs were comparable |

| Stephenson et al. 201832 | October 2011–June 2014 |

Treatment: Patients prescribed warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban or apixaban Population: Patients with nonvalvular AF Mean age: 65.6 y Female: 39.4% |

Design: Hybrid observational study Setting: Conducted in 14 institutions in the USA |

Patient‐reported adherence using Morisky medication adherence scale MMAS‐8 Duke anticoagulation treatment scale, administered at baseline, and at 4, 8 and 12 months |

675 patients 271 in warfarin group 266 dabigatran group 128 rivaroxaban group 10 in apixaban group |

Validated patient‐reported tool. Measures medication taking behaviours and explores circumstances influencing adherence. Scores 0–8 DASS score 4 points to measure QoL and satisfaction among OAC treatment |

Adherence: Mean MMAS scores were similar among all 4 groups in the initial and follow up surveys Satisfaction: DASS scores were lower for dabigatran and rivaroxaban cohort indicating greater treatment satisfaction |

| de Caterina et al., 201833 | 2012–2013 |

Treatment: On stable VKA or switched to NOAC (rivaroxaban, dabigatran or apixaban) Population: Patients with AF Mean age: 72 y Female: 37% |

Design: Prospective study PREFER in AF registry sub study Setting: Conducted in 7 European countries |

Patient‐reported QoL and satisfaction using PACT‐ Q2 and EQ‐5D‐5 L questionnaires, administered at baseline and at 1 y follow‐up | 2950 patients completed the questionnaires, excluded patients stable on NOAC. 2102 patients on stable treatment with VKA, 213 patients switched from VKA to NOAC | PACT Q2 questions about satisfaction EQ‐5D‐5 L questions investigate several aspects of QoL. | Satisfaction: Switched patients more often reported bruising or bleeding, dissatisfaction with treatment, mobility problems and anxiety/depression traits with VKA that may have influenced the switch to NOAC. |

| Koretsune et al., 201834 | April 2012 |

Treatment: Rivaroxaban in patients previously on warfarin Population: Nonvalvular AF patients Mean age: 73.6 y Female: 35.5% |

Design: Postmarketing surveillance study of a prospective study Setting: 124 sites in Japan |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction ACTS and TSQM Ver II, administered at baseline and at 3 and 6 months | 665 patients included in the study |

ACTS burden and benefits TSQM Ver II |

Satisfaction: Statistically significant improved TSQM scores in the rivaroxaban group at month 3 and 6 compared to baseline in all 4 domains (P < .001). Significantly (P < .001) less burden at 3 months (54.6) and month 6 (54.5) vs baseline (51.0), and benefit remained stable in the rivaroxaban group |

| Larochelle et al., 201835 | February 2013–December 2014 |

Treatment: Patients newly prescribed an oral anticoagulant (either warfarin or DOAC, apixaban, rivaroxaban or dabigatran) Population: Patient with nonvalvular AF Mean age: 71.35 y Female: ~60% |

Design: Prospective observational study Setting: Hospitals in Canada |

Patients expectations and satisfaction with oral anticoagulation treatment using PACT Q1 and PACT Q2 questionnaires, administered before treatment and at 3 and 6 months postdischarge | 159 patients included (71 on warfarin and 88 on DOAC, mainly rivaroxaban) |

PACT Q = perception of anticoagulant treatment questionnaire Q1 = 7 questions on patient expectations Q2 = 20 questions on treatment convenience, burden of disease and treatment and anticoagulant treatment satisfaction. |

Expectations: No significant differences in treatment expectations, patients prescribed warfarin had a slightly higher expectation of having side effects. Satisfaction: Convenience scores were similar at 3 months but much higher in DOAC group at 6 months (86.29 vs 90.97, P < .05). Satisfaction scores were similar between groups. |

| Benzimra et al., 201836 | June 2013–November 2015 |

Treatment: Patients receiving oral anticoagulants VKA/DOAC (dabigatran, rivaroxaban or apixaban), or switched treatments Population: Patient with AF Mean age: 74.3 y Female: 41% |

Design: Real‐life observational descriptive cross‐sectional study Setting: Various recruitment sites in France |

Quality of life, treatment satisfaction and adherence using 3 validated questionnaires‐ EQ‐5D 3‐level visual analogue scale, perception of anticoagulation treatment questionnaire PACT‐Q2, 8 item Morisky scale medication adherence scale MMAS‐8, administered once over the phone to patients for at least 3 months treatment | 200 patients (89 on VKA, 52 on DOAC, 50 switched to DOAC, 9 switched to VKA) |

EQ‐5D: 5 dimensions mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Score 0–100 PACT‐Q2 assess treatment satisfaction with anticoagulant assesses convenience, burden and satisfaction.

MMAS‐8 assesses adherence to therapy through 8 questions. |

HRQoL: HRQoL: EQ‐5D scores were similar in all groups but higher in the DOAC group. Overall QoL on the EQ‐5D visual analogue scale tended to be better in the DOAC group but this was not statistically significant. Satisfaction: Convenience and satisfaction scores were high in all 3 groups but significant difference in favour of the DOAC group (P < .001) Adherence: Adherence scores were high for all 3 groups with no significant difference between the groups. |

| Okumura et al. 201837 | September 2013 and December 2015 |

Treatment: Patients on anticoagulation (VKA/DOAC) Population: Patients with non valvular AF Mean age: 72 y Female: 22.6% |

Design: Substudy of SAKURA AF registry Questionnaire‐based prospective study Setting: 40 institutions in Japan |

Patients satisfaction with anticoagulant treatment using ACTS and TSQM Ver II, administered once |

1475 patients: 654 in DOAC group (241 dabigatran, 331 rivaroxaban and 1 edoxaban) in 821 warfarin group. 513 completed the ACTS questionnaire |

ACTS: 17‐item questionnaire to measure patient satisfaction addressing burden and benefits. The TSQM II covers 4 domains, effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction. | Satisfaction: There were no significant differences in the TSQM II questionnaire between the groups. The ACTS burden scores were significantly higher for the DOAC group than the warfarin group showing greater satisfaction with treatment. |

| Fernandez et al., 201838 |

ALADIN Study: September 2014 to March 2015 ESPARTA Study: October 2015 to March 2016 |

Treatment: Patients prescribed VKA or DOAC Population: Patients with nonvalvular AF Mean age: 78.5 y Female: 48.95% |

Design: 2 different cross‐sectional studies combined (ALADIN and ESPARTA studies) Setting: Various departments in Spain |

Patient satisfaction with anticoagulant treatment using ACTS questionnaire, administered at regular single visit, patients on at least 3 months treatment |

ALADIN study: 472 patients ESPARTA study: 837 patients. 1309 patients in total, 902 VKA group ad 407 DOAC group |

ACTS is patient‐reported measure of satisfaction with anticoagulation.12 items that assess perceived burdens, 4 items to assess perceived benefits | Satisfaction: Overall satisfaction with oral anticoagulation was high. Patients taking DOACs showed a lower perceived burden with anticoagulation therapy (48.8 vs 53.1, P < .001). Perceived benefits were higher in DOAC group (11.06 vs 11.99, P < .001). |

| Obamiro et al., 201839 | Not specified |

Treatment: Prescribed oral anticoagulants Population: Patients with AF Age range: 18–>65 y Female: 68% |

Design: Secondary analysis of the Australian oral anticoagulation survey Setting: Conducted through online recruitment in Australia |

Predictors of adherence and patient related factors of adherence using Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS‐8), anticoagulation knowledge tool and PACT Q1 and Q2 questionnaires |

386 patients (warfarin: 100 patients, apixaban: 121 patients, rivaroxaban: 123 patients, dabigatran: 42 patients) |

MMAS‐8 to assess levels of adherence. AKT to assess OAC knowledge and perception of anticoagulation treatment questionnaires assessing treatment expectation, global convenience and satisfaction. |

Adherence: No significant difference in adherence seen between patients taking warfarin and DOACs. Patients in the high adherence group showed a higher anticoagulation knowledge. Satisfaction: Satisfaction scores were greater in the medium adherence groups. |

| Patients with VTE (PE and DVT) | |||||||

| Bamber et al. 201340 | March 2007 to Sept 2009 |

Treatment: Rivaroxaban vs enoxaparin/warfarin for population: Patients with DVT Mean age: 56.8 y Female: 42.4% |

Design: RCT Substudy analysis of EINSTEIN DVT study Setting: Conducted in 7 countries (USA, UK, Canada, Netherlands, France, Germany and Italy) |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction using ACTS score, assessed at 12 months of treatment | 1472 patients | ACTS 15‐point score burden and benefits |

Satisfaction: Clinically significant reduction in ACTS burden (55.2 vs 52.6, P < .0001) and improvement in ACTS benefit (11.7 vs 11.5, P = .006) in rivaroxaban group (compared with warfarin) |

| Prins et al., 201441 | March 2007–March 2011 |

Treatment: Rivaroxaban vs standard therapy (enoxaparin/warfarin) Population: Patient with PE Mean age: 58 y Female: 44% |

Design: Sub analysis of EINSEIN PE study Setting: 7 countries USA, UK Canada, Netherlands, France, Germany and Italy |

Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction using ACTS and TSQM Ver II, assessed at 1, 2, 3, 6 and 12 months |

2397 patients (1200 in rivaroxaban arm and 1197 in enoxaparin/warfarin arm) |

ACTS 15‐point scale burden scale and benefit scale |

Satisfaction: Rivaroxaban group reported statistically significant increase in ACTS benefit (11.9 vs 11.4, P < .0001) and less ACTS burden (55.4 vs 51.9, P < .0001)

Statistically significant improved TSQM II scores in the rivaroxaban group P < .0001 for all 4 factors, effectiveness, side‐effects, convenience and global satisfaction |

| Carrothers et al., 201442 | May 2010 to December 2011 |

Treatment: Patients prescribed rivaroxaban Population: VTE prophylaxis following lower limb arthroplasty Mean age: 66 y Female: 61% |

Design: Prospective study Setting: single orthopaedic Centre in Canada |

Patient‐reported compliance using self‐administered questionnaire, administered 14 days postsurgery and 6 weeks after treatment at the follow‐up appointment | 2621 patients attended the 6‐week appointment | Yes/no questionnaire developed by the investigators to measure adherence/compliance, | Compliance: Majority of patients were compliant with rivaroxaban treatment (83%), noncompliance was associated with older age, lower body mass index and lower preoperative haemoglobin. |

| Patients with AF and VTE | |||||||

| Castellucci et al., 201543 | September 2012–September 2013 |

Treatment: Patients on oral anticoagulants (VKA, rivaroxaban, dabigatran and apixaban) Population: VTE and AF patients Mean age: 63 y Female: 42.7% |

Design: Cross‐sectional survey setting: Conducted in 1 anticoagulant clinic in Canada | Self‐reported anticoagulant adherence using 4 item Morisky score, administered once | 500 patients (367 on VKA, 130 on DOACS) | 4‐item Morisky adherence scale used | Adherence: Self‐reported adherence using the 4 item Morisky scale was 56.2% on VKA and 57.1% on DOAC. Adherence was similar in groups. |

ACTS, Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale; AF, atrial fibrillation; BD, twice a day; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; EQ‐5D, EuroQol 5D questionnaire (5 dimensions); HRQoL, health‐related quality of life; NOAC, new oral anticoagulant; QoL, quality of life; PACT, Perception of Anticoagulation Questionnaire; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TSQM Ver II, treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication version II ; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

2.6. Classification of outcomes

The outcome measures were categorized into 3 main groups: HRQoL; patient‐reported satisfaction; and patient‐reported adherence/compliance or expectations related to anticoagulation treatment with DOACs.

2.7. Assessment of quality and risk of bias in included studies

The lead author independently assessed the risk of bias of each of the included studies and discussed their assessments with other 2 authors to achieve consensus. The 6‐item risk of bias assessment was used as it is a validated method of analysing bias within randomized controlled trials.11, 44 The criteria for judging include random sequence generation of the study sample, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other issues that may indicate bias. The modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale was selected because it was easier to use and considered reliable to measure biasness in cross‐sectional studies.45 Each of the selected cross‐sectional studies was evaluated for selection, comparability and outcome bias. The lead author rated each paper using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale assessment methods for selecting study participants, methods to control confounding, using appropriate statistical methods and methods for measuring outcome variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results and study characteristics

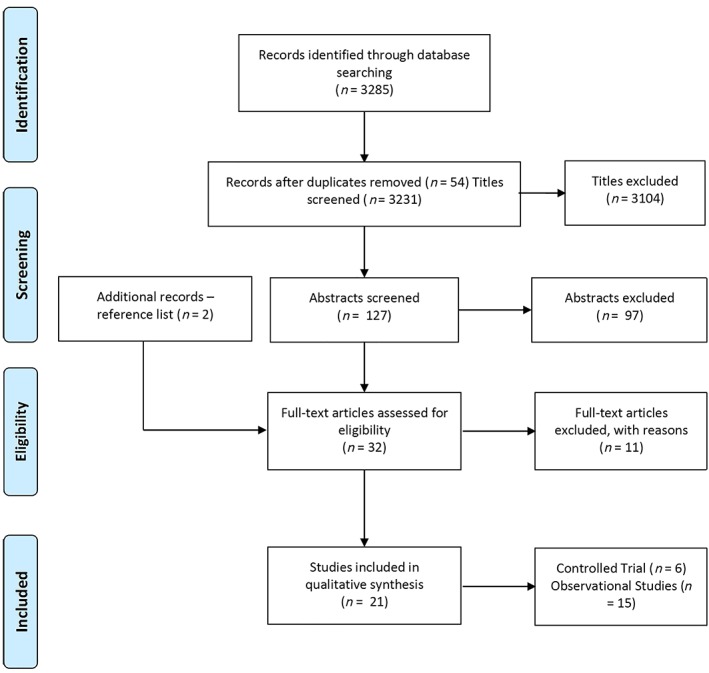

The search yielded 3285 unique titles (1964 from PubMed, CINAHL, Medline and EMBASE, with an additional 1321 titles from SCOPUS, Springer Link and Google Scholar). After removal of duplicate records, 3231 abstracts were screened. Of these, 3104 studies were excluded. Of the remaining 127 articles, 97 were excluded as they did not describe original research or did not illustrate PROs or focussed on warfarin alone. The search yielded 11 articles that were excluded because they involved investigations on adherence or persistence based on pill‐taking patterns, tablet counting or prescription fill analysis rather than PROs. A total of 21 studies were ultimately included in the review—6 controlled trials and 15 observational studies (Figure 1). The 21 studies evaluated PROs or quality of life (QoL), using a validated tool, associated with the use of DOACs. The controlled trials (n = 6) included 5 randomized and 1 nonrandomized trial (see Table 1). Controlled trials were used as they provide larger scale trials within controlled environments; however, due to being sponsored by industry these often may contain an element of bias and not present the full patient overview. Real‐world observational and cross‐sectional studies provide actual patient experience and use of the treatment in practice. Of the 6 controlled trials, 5 were conducted in multiple countries (including UK, USA, Canada, Netherlands, France, Germany and Italy)23, 24, 25, 40, 41 and 1 was conducted in Japan.26 The observational studies (n = 15) used the following study designs: 11 prospective studies conducted in Spain, France, Canada, Japan, USA, Australia and Europe. Four of the studies were cross‐sectional studies conducted in Spain, France and Canada (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process (PRISMA flow diagram)

3.2. Risk of bias within studies

In the case of controlled trials, 5 studies used randomized methods to generate the sequence,23, 24, 26, 40, 41 and 1 study used some form of data checking for patient selection (see Table 2).25 However, only 3 studies clearly described a form of concealed allocation and personnel and participant blinding.23, 40, 41 Hence, none of the studies satisfied all 6 key criteria together.44 In respect to the observational studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used for quality assessment (see Table 3). Of the 15 observational studies, 6 were good studies with a score of 7–8 points.27, 30, 32, 36, 39 Eight of the studies were regarded as satisfactory studies with a score of 5–6 points.28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38 Only 1 study was considered as an unsatisfactory study with a score of only 4 points due to the lack of use of a validated PRO tool.42 Quality issues often lacking were blinding of the outcome assessment, identification of potential confounders, assessment of the subjects' likelihood of the outcome upon enrolment, and validity and reliability of the outcome assessment tools.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment (Cochrane randomized controlled trials) for controlled trials.

| Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Binding‐participants and personnel | Binding‐outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamber et al. 2013 | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| Coleman et al. 2016 | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Hohnloser et al. 2015 | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Koretsune et al. 2017 | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Monz et al. 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Prins et al. 2015 | + | + | + | − | − | − |

+ = low risk of bias.

– = high risk of bias.

? = unclear risk of bias.

Table 3.

Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale and analysis of observational studies

| Sample representativeness | Sample size | Nonrespondents | Ascertainment of exposure | Comparability | Assessment of outcome | Statistical test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegret et al. 2014 | Selected | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| Benzimra et al. 2018 | Selected | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| Carrothers et al. 2014 | Selected | * | * | ‐ | * | * | ‐ |

| Castellucci et al. 2015 | Selected | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| De Caterina et al. 2018 | Selected | * | ‐ | ** | * | * | ‐ |

| Fernandez et al. 2018 | Selected | * | * | ** | * | * | ‐ |

| Hanon et al. 2016 | * | * | ‐ | ** | * | * | ‐ |

| Keita et al. 2017 | Selected | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| Koretsune et al. 2018 | Selected | * | * | ** | * | * | ‐ |

| Larochelle et al. 2018 | Selected | * | ‐ | ** | * | * | * |

| Marquez‐Contreras et al. 2017 | * | * | * | * | * | * | ‐ |

| Muruaga et al. 2017 | Selected | * | ‐ | ** | * | * | * |

| Obamiro et al. 2018 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

| Okumura et al. 2018 | Selected | * | ‐ | ** | * | * | * |

| Stephenson et al. 2018 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * |

7–8 * = good studies.

5–6 * = satisfactory studies.

0–4 * = unsatisfactory studies.

3.3. Study outcomes

HRQoL was reported in 5 studies and used the Euro‐QoL utility and visual analogue scores, which covered 5 dimensions (consisting of mobility, autonomy, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) or the Sawicki questionnaire (which is a 32‐item questionnaire grouped covering general treatment satisfaction, self‐efficacy, strained social network, daily hassles and distress).14, 46, 47 The majority of the studies (14 studies) described: patient‐reported treatment satisfaction, which had been measured using the ACTS (a 15‐point scale to score burden and benefit); or treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM) version II, which assesses 4 subscales of convenience, effectiveness, global satisfaction and side effects based on Likert scales)15, 16; and medication‐related, review or intervention‐related, and adverse outcomes. Overall, the outcomes were diverse with differing definitions, methods of data collection, varying time points and different reporting methods.

3.3.1. Patient‐reported satisfaction

Greater satisfaction with DOACs was reported in 5 of the included studies using the ACTS tool. These studies showed a significant reduction in the burden score and a higher benefits score illustrating more satisfaction with DOAC treatment.25, 28, 37, 38, 40, 41 One study demonstrated a reduced ACTS burden score but stable or no change in the benefit score.26, 34 Only 2 studies showed increased satisfaction in the DOAC group based on the PACT Q2 tool.35, 36 Another study that used the PACT Q2 tool showed high satisfaction in both anticoagulation groups, VKA and DOAC.30 One of the studies reported inconclusive results or dissatisfaction with DOAC therapy; however, these patients had been switched from warfarin and the questionnaire may correlate to the patients' experiences of warfarin treatment.33 Three of the studies that utilized the TSQM questionnaire reported greater patient satisfaction with DOAC treatment scores.24, 26, 41 Okumura et al.37 reported no difference in satisfaction when using the TQSM score. Stephenson et al.32 used the Duke Anticoagulation Treatment Scale, which confirmed patient satisfaction with DOAC treatment. Satisfaction with VKA vs DOAC was also analysed by Contreras Muruaga et al.31; however, the patient population was the same as another study38 and therefore these results were excluded from this review to avoid duplication.

3.3.2. HRQoL

HRQoL was investigated by 6 different studies, which utilized either the Euro Qol 5 dimension of the Sawicki questionnaires. All 6 studies reported that HRQol was similar among patients on VKA and DOACs.23, 27, 29, 30, 31, 36 Contreras Muruaga et al.31 demonstrated that a higher QoL was associated with longer time in therapeutic range and better INR control. Four of the studies described a higher HRQoL score in the DOAC group, but this was not statistically significant.27, 29, 30, 36 Keita et al.30 showed that this higher QoL score can be attributed to the lack of blood monitoring associated with DOACs. Marques‐Contreras et al.,29 highlighted that a significantly higher QoL score was confirmed in patients with established compliance after 12 months of treatment.

3.3.3. Patent‐reported expectations, compliance or adherence

Larochelle et al.35 used the perception of anticoagulation treatment questionnaire to determine patient expectation with anticoagulation treatment prior to initiation. The study found that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups; however, there was a greater expectation of adverse effects in the warfarin group.

Patient‐reported compliance was explored by Carrothers et al.42 using an investigator‐developed questionnaire that showed that the majority of patients prescribed rivaroxaban were compliant with treatment.

Patient‐reported medication adherence was investigated by 5 studies using the 8‐point Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS‐8).30, 32, 36, 39 Castellucci et al.43 used an abridged 4‐point version of the MMAS tool. All 5 studies indicated that adherence was similar among patients treated with VKAs and DOACs. Obamiro et al.39 highlighted that a higher adherence score was observed in the patient group, which exhibited a higher knowledge of anticoagulation treatment.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review provides the first overview of the use of PROs in anticoagulant treatment and has categorized an increasing body of evidence to establish the importance of PROs in patients treated with DOACs. The systematic search for this review yielded 21 articles (6 controlled studies and 15 observational studies) from 3231 screened articles. The studies focussed on PROs such as patient‐reported satisfaction, expectations, compliance and adherence as well as HRQoL. The majority of the studies described enhanced satisfaction in patients prescribed DOAC treatment using self‐report scales. Studies highlighting patient‐reported expectations, adherence and compliance using the MMAS‐8 tool showed that adherence was similar in DOAC and warfarin groups; however, patients prescribed warfarin had more expectations of adverse events. It was identified that patients with greater knowledge of their anticoagulant treatment were more likely to adhere. HRQoL was investigated by some studies, which demonstrated that there was no significant difference between the 2 groups. Increased HRQoL was observed in the DOAC group for a couple of studies; however, this was not statistically significant. In contrast, a reduced HRQol is observed in patients prescribed warfarin, which correlates with poor INR control, a factor which does not influence DOAC treatment.48

Although DOACs are not associated with the same pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamic issues as warfarin, they have presented with additional concerns surrounding medication adherence and therapeutic efficacy. Hence, PROs are a beneficial outcome measure to determine patient satisfaction, adherence and compliance with DOAC treatment. PROs offer a unique perspective of treatment effectiveness without the invasive blood testing and monitoring requirements associated with warfarin. These can often be more reliable that physiological parameters and informal interviews through the use of optimal validated tools as a method of categorising and measuring patient outcomes.49

Warfarin and DOACs are equally as effective in the prevention or treatment of VTE and stroke.50 DOACs are associated with less bleeding risk and net benefit when compared to warfarin.51 However, the simple medication regime and lack of therapeutic monitoring associated with DOACs are likely to result in more patients and physicians opting and preferring DOAC treatment with proven satisfaction, adherence and likely HRQoL. Satisfaction has been reported with warfarin treatment, which comprises less complicated regimes and monitoring and management methods including self‐monitoring, pharmacist inclusion or single point of testing at home.52, 53, 54

Near‐patient testing and self‐monitoring with warfarin have shown improved satisfaction rates over standard clinic monitoring with warfarin treatment. Studies have shown an improved quality of anticoagulation in patients who self‐monitor and self‐adjust their doses, which results in an overall reduced incidence of VTE by around 50%, a 33% reduction in major haemorrhage and a reduction in mortality from all causes.55

The World Health Organization has reported that half of the patients prescribed regular medication for chronic illness do not adhere to their prescribed regimes.56 Factors that affect adherence are multiple and complicated in nature. Factors of nonadherence can be patient related (lack of literacy, involvement or engagement), physician related (prescribing of complex regimens or ineffective communication) or healthcare system related.56 Barriers to adherence and medication taking behaviour is complex and challenging to overcome; therefore, patient satisfaction of treatment plays a fundamental role in enhancing patient concordance, experience and overall preference for taking their medications for chronic conditions. Further evidence suggests that enhanced patient knowledge about anticoagulation treatment results in enhanced patient satisfaction; therefore, pharmacists are the best placed experts in medicines to provide thorough counselling to patients through effective communication.57, 58, 59

Healthcare professionals play an elemental role in educating and motivating patients to engage with their treatment plan to ensure maximum adherence with medication. Empowering and motivating patients as well as involving them in the decision‐making process is likely to provide profound benefit to the patient and overall healthcare economy due to reduced incidence of complications and costly hospitalizations. The European Heart Rhythm Association have issued a consensus statement, which also highlights the importance of patient education and a vital element in the management of cardiac arrhythmias including AF. The European Heart Rhythm Association suggests that all patients should receive individualized and specially designed information which is specific to their needs, condition and treatment and repeated over time.60 A clear link has been established between greater treatment satisfaction resulting in enhanced adherence to treatment for chronic conditions.61 Patients reporting greater satisfaction, improved quality of life and therefore higher adherence to DOACs are more likely to concord with DOAC treatment, resulting in successful treatment, fewer complication of stroke or VTE and reduced mortality. Incorporating shared decision‐making processes into consultations is the optimal approach to achieve maximum patient satisfaction and improved QoL.60

Warfarin, although an inexpensive drug, requires costly monitoring and is resource intensive, which patients are known to dislike due to the regular clinic appointments and blood tests with up to 13 appointments a year and <65% of time spent in therapeutic range with a consequent increase in risk of stroke.62 DOACs by contrast are costly drugs and this has been a nature of debate in order to achieve the most cost‐effective anticoagulant treatment available on the National Health Service.

Cost effectiveness of DOACs is highly dependent and directly related to the costs of the alternative, VKA, with the associated adequate quality of monitoring and therapeutic control.63 However, this can be balanced with the enhanced patient preference of no monitoring with DOACs, indicating higher satisfaction, preference and overall QoL with DOACs.

4.1. Possible limitations

This review comprised a comprehensive literature search and extensive scrutiny of relevant articles for inclusion in order to minimize the risk of bias. However, meta‐analysis and robust conclusions cannot be drawn because of significant heterogeneity in validated tool used, outcome measures and publication bias. Overall, this review had several limitations that may affect its generalizability, including language bias (only English‐language databases and journals were searched), selection bias (allocation concealment), and detection bias or performance bias (blinding related). Blinding of all study participants, personnel, and outcome assessors was not possible across all included studies because of the nature of the outcomes reported and study design (real‐world observational studies). Patients and professionals participating the in the studies were aware of the nature of the study carried out and intention behind completing the questionnaires chosen. Moreover, reporting bias cannot be ruled out. Finally, a limitation of PROs is that they exclude patients with disability or low literacy skills and therefore may not be representative of the patient population or present an accurate picture of patient acceptance of treatment; therefore, further work is needed to ensure inclusion of these patient groups.64

5. CONCLUSIONS

This review has established that the majority of patients are satisfied and would therefore prefer anticoagulation with DOACs when compared to warfarin for VTE and AF treatment and long‐term prevention of stroke. This has been identified by the increased satisfaction, adherence and HRQoL experienced by patients on DOACs, which is likely to have substantial impact on the National Health Service burden, incidence of stroke complications and overall reduction in morbidity and mortality. However, heterogeneity in the analysed studies (randomized and observational) does not allow firm conclusions and statistical inference (meta‐analysis). More original work should be carried out to strengthen this evidence.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare. All authors have read and approved the final draft. This review is part of a PhD project.

Afzal SK, Hasan SS, Babar ZU‐D. A systematic review of patient‐reported outcomes associated with the use of direct‐acting oral anticoagulants. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2652–2667. 10.1111/bcp.13985

REFERENCES

- 1. Brunton G, Richardson M, Stokes G, et al. The effective, safe and appropriate use of anticoagulation medicines. A systematic overview of reviews. In: Facility DoHaSCR, ed. May 2018.

- 2. Gomez‐Outes A, Terleira‐Fernandez AI, Calvo‐Rojas G, Suarez‐Gea ML, Vargas‐Castrillon E. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miesbach W, Seifried E. New direct oral anticoagulants—current therapeutic options and treatment recommendations for bleeding complications. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(4):625‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saliba W. Non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: new choices for patient management in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2015;15(5):323‐335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139‐1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883‐891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981‐992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2093‐2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health NIf, Excellence C . Anticoagulants, including non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs). In: NICE London; 2016.

- 10. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893‐2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Green S, Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2005. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doward LC, McKenna SP. Defining patient‐reported outcomes. Value Health. 2004;7:S4‐S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient‐reported outcome measures and patient‐reported experience measures. BJA Education. 2017;17(4):137‐144. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Xie F, Kong MC, Lee LH, Ng HJ, Ko Y. Patient‐reported health preferences of anticoagulant‐related outcomes. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;40(3):268‐273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cano SJ, Lamping DL, Bamber L, Smith S. The anti‐clot treatment scale (ACTS) in clinical trials: cross‐cultural validation in venous thromboembolism patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prins MH, Marrel A, Carita P, et al. Multinational development of a questionnaire assessing patient satisfaction with anticoagulant treatment: the 'Perception of anticoagulant treatment Questionnaire' (PACT‐Q©). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Samsa G, Matchar DB, Dolor RJ, et al. A new instrument for measuring anticoagulation‐related quality of life: development and preliminary validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wild D, Murray M, Shakespeare A, Reaney M, von Maltzahn RJ. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction measures for long‐term anticoagulant therapy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(3):291‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan X, Patel I, Chang JJ. Review of the four item Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS‐4) and eight item Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS‐8). Innov Pharm. 2014;5(3):5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Generalova D, Cunningham S, Leslie SJ, Rushworth GF, McIver L, Stewart D. A systematic review of clinicians' views and experiences of direct‐acting oral anticoagulants in the management of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(12):2692‐2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;151(4):264‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Monz BU, Connolly SJ, Korhonen M, Noack H, Pooley J. Assessing the impact of dabigatran and warfarin on health‐related quality of life: results from an RE‐LY sub‐study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2540‐2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hohnloser SH, Cappato R, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction and budget impact with rivaroxaban vs. standard therapy in elective cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a post hoc analysis of the X‐VeRT trial. Europace. 2016;18(2):184‐190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coleman CI, Haas S, Turpie AG, et al. Impact of switching from a vitamin K antagonist to rivaroxaban on satisfaction with anticoagulation therapy: the XANTUS‐ACTS substudy. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(10):565‐569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koretsune Y, Ikeda T, Kozuma K, et al. Patient satisfaction after switching from warfarin to apixaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: AGAIN study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1987‐1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alegret JM, Vinolas X, Arias MA, et al. New oral anticoagulants vs vitamin K antagonists: benefits for health‐related quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(7):680‐684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hanon O, Chaussade E, Gueranger P, Gruson E, Bonan S, Gay A. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. A French observational study, the SAFARI study. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0166218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marquez‐Contreras E, Martell‐Claros N, Gil‐Guillen V, et al. Quality of life with rivaroxaban in patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrilation by therapeutic compliance. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(3):647‐654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keita I, Aubin‐Auger I, Lalanne C, et al. Assessment of quality of life, satisfaction with anticoagulation therapy, and adherence to treatment in patients receiving long‐course vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1625‐1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Contreras Muruaga MDM, Vivancos J, Reig G, et al. Satisfaction, quality of life and perception of patients regarding burdens and benefits of vitamin K antagonists compared with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Comp Eff Res. 2017;6(4):303‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stephenson JJ, Shinde MU, Kwong WJ, Fu AC, Tan H, Weintraub WS. Comparison of claims vs patient‐reported adherence measures and associated outcomes among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation using oral anticoagulant therapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:105‐117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Caterina R, Bruggenjurgen B, Darius H, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in patients with atrial fibrillation on stable vitamin K antagonist treatment or switched to a non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant during a 1‐year follow‐up: a PREFER in AF registry substudy. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111(2):74‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koretsune Y, Kumagai K, Uchiyama S, et al. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with rivaroxaban in Japanese non‐valvular atrial fibrillation patients: an observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(12):2157‐2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Larochelle J, Brais C, Blais L, et al. Patients' perception of newly initiated oral anticoagulant treatment for atrial fibrillation: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(8):1239‐1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Benzimra M, Bonnamour B, Duracinsky M, et al. Real‐life experience of quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and adherence in patients receiving oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:79‐87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okumura Y, Yokoyama K, Matsumoto N, et al. Patient satisfaction with direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin. Int Heart J. 2018;59(6):1266‐1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suarez Fernandez C, Castilla‐Guerra L, Cantero Hinojosa J, et al. Satisfaction with oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:267‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Obamiro KO, Chalmers L, Lee K, Bereznicki BJ, Bereznicki LR. Adherence to oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: an Australian survey. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(4):337‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bamber L, Wang MY, Prins MH, et al. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy in the treatment of acute symptomatic deep‐vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(4):732‐741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prins MH, Bamber L, Cano SJ, et al. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy in the treatment of pulmonary embolism; results from the EINSTEIN PE trial. Thromb Res. 2015;135(2):281‐288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carrothers AD, Rodriguez‐Elizalde SR, Rogers BA, Razmjou H, Gollish JD, Murnaghan JJ. Patient‐reported compliance with thromboprophylaxis using an oral factor Xa inhibitor (rivaroxaban) following total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1463‐1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Castellucci LA, Shaw J, van der Salm K, et al. Self‐reported adherence to anticoagulation and its determinants using the Morisky medication adherence scale. Thromb Res. 2015;136(4):727‐731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wells GJ, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle‐Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta‐analysis. 2013. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 46. Devlin NJ, Krabbe PF. The development of new research methods for the valuation of EQ‐5D‐5L. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(S1):1‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sawicki PT. A structured teaching and self‐management program for patients receiving oral anticoagulation: a randomized controlled trial. Working group for the study of patient self‐management of oral anticoagulation. Jama. 1999;281(2):145‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hasan S, Teh K, Ahmed S, Chong D, Ong H, Naina B. Quality of life (QoL) and international normalized ratio (INR) control of patients attending anticoagulation clinics. Public Health. 2015;129(7):954‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Valderas J, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient‐reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sindet‐Pedersen C, Pallisgaard JL, Olesen JB, Gislason GH, Arevalo LC. Safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism‐a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Thromb Res. 2015;136(4):732‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. López‐López JA, Sterne JA, Thom HH, et al. Oral anticoagulants for prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: systematic review, network meta‐analysis, and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Meyer S, Frei CR, Daniels KR, et al. Impact of a new method of warfarin management on patient satisfaction, time, and cost. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(11):1147‐1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carris NW, Hwang AY, Smith SM, et al. Patient satisfaction with extended‐interval warfarin monitoring. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;42(4):486‐493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hixson‐Wallace JA, Dotson JB, Blakey SA. Effect of regimen complexity on patient satisfaction and compliance with warfarin therapy. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2001;7(1):33‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Heneghan C, Alonso‐Coello P, Garcia‐Alamino J, Perera R, Meats E, Glasziou P. Self‐monitoring of oral anticoagulation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):404‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Paper presented at: Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57. Sahm L, Quinn L, Madden M, Richards HL. Does satisfaction with information equate to better anticoagulant control? Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;33(3):543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Obamiro KO, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR. A summary of the literature evaluating adherence and persistence with oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2016;16(5):349‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang Y, Kong MC, Lee LH, Ng HJ, Ko Y. Knowledge, satisfaction, and concerns regarding warfarin therapy and their association with warfarin adherence and anticoagulation control. Thromb Res. 2014;133(4):550‐554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lane DA, Aguinaga L, Blomström‐Lundqvist C, et al. Cardiac tachyarrhythmias and patient values and preferences for their management: the European heart rhythm association (EHRA) consensus document endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulacion Cardiaca y Electrofisiologia (SOLEACE). Europace. 2015;17(12):1747‐1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barbosa CD, Balp M‐M, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Anticoagulation UK . Out of range: Audit of anticoagulation management in secondary care in England. In: April 2018.

- 63. You JH. Novel oral anticoagulants versus warfarin therapy at various levels of anticoagulation control in atrial fibrillation—a cost‐effectiveness analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(3):438‐446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Easton P, Entwistle VA, Williams B. Health in the 'hidden population' of people with low literacy. A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]