Abstract

Aims

Metformin may have clinical benefits in dialysis patients; however, its safety in this population is unknown. This systematic review evaluated the safety of metformin in dialysis patients.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library were searched for randomised controlled trials and observational studies evaluating metformin use in dialysis patients. Three authors reviewed the studies and extracted data. The primary outcomes were mortality, occurrence of lactic acidosis and myocardial infarction (MI) in patients taking metformin during dialysis treatment for ≥12 months (long term). Risk of bias was assessed using Risk Of Bias In Nonrandomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS‐1). Overall quality of evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

Results

Fifteen observational studies were eligible; 7 were prospective observational studies and 8 were case reports/case series. No randomised controlled trials were identified. The 7 prospective observational studies (n = 194) reported on cautious metformin use in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis. Only 3 provided long‐term follow‐up data. In 2 long‐term studies of metformin therapy (≤1000 mg/d) in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD), 1 reported 6 deaths (6/83; 7%) due to major cardiovascular events (3 MI) and the other reported no deaths (0/35). One long‐term study of metformin therapy (250 mg to 500 mg thrice weekly) in patients undergoing haemodialysis reported 4 deaths (4/61; 7%) due to major cardiovascular events (2 MI). These findings provide very low‐quality evidence as they come from small observational studies.

Conclusion

The evidence regarding the safety of metformin in people undergoing dialysis is inconclusive. Appropriately designed randomised controlled trials are needed to resolve this uncertainty.

Keywords: dialysis, lactic acidosis, metformin, mortality, systematic review

What is already known about this subject

Metformin is currently contraindicated in patients undergoing dialysis owing to concerns around safety, namely the perceived increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin has been associated with benefits outside glycaemic control, including cardiovascular improvement. This is particularly pertinent in dialysis patients for whom cardiovascular causes of death are common.

What this study adds

This review identified a few small observational studies which evaluated the safety of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis. These suggest that cautious, monitored use of metformin (not exceeding 1 g daily) did not result in lactic acidosis, adverse mortality or cardiovascular outcomes.

Although these findings are currently based on very low‐quality evidence owing to the nature and size of the studies identified, they provide important information to guide further research in this area.

1. INTRODUCTION

Metformin is the first‐line pharmacotherapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1, 2 In contrast to most other oral anti‐hyperglycaemic medicines,3, 4 metformin does not cause hypoglycaemia5 or weight gain.6, 7 It has also been identified as cardioprotective in a subgroup analysis of the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS).3 These benefits, and the well‐characterised safety profile of metformin, and its low cost, contribute to its widespread use.

Adverse effects associated with metformin are largely gastrointestinal (e.g. anorexia, diarrhoea, abdominal pain) and are usually mild.8 However, the association of metformin use with lactic acidosis, a life‐threatening condition, is a concern reflected in regulatory labels. Lactic acidosis (lactate concentrations >5 mmol/L and arterial pH <7.35)9 has a mortality rate of ~25%.10 As metformin is excreted unchanged by the kidneys11 there are concerns that metformin accumulation in renal impairment may result in lactic acidosis. One hypothesis is that metformin may exacerbate lactic acidosis caused by severe gastroenteritis, subsequent dehydration and renal failure.12 The risk of lactic acidosis and death has led regulatory bodies to contraindicate metformin use in patients with renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) although guideline groups increasingly support lower eGFR cut‐offs.13, 14, 15

Lactic acidosis has occurred during metformin treatment, and in this context has been termed metformin‐associated lactic acidosis (MALA). Although the relationship between MALA and metformin plasma concentrations is unclear,16 Lalau et al17 suggested that plasma concentrations >5 mg/L should be regarded pragmatically as markedly elevated. The prevalence of MALA is rare (<10 cases per 100 000 patient‐years).18 Furthermore, mortality risk appears dose‐dependent.19 For example, 1 observational study19 of metformin use in patients with advanced (~stage 5) chronic kidney disease (CKD) identified that doses >1000 mg/d were associated with greatest risk of mortality.19 However, this study did not include dialysis patients and metformin dose was not decreased in patients with impaired renal function.

Contrary to concerns of increased risk of lactic acidosis and death, there are suggestions that metformin may have clinical benefits for patients with diabetes undergoing dialysis due to its cardio‐protective effects.3, 20, 21 For example, a recent systematic review20 found that metformin use was associated with reduced all‐cause mortality in patients with CKD. To date, there has been no comprehensive evaluation of the use and safety of metformin in patients with end‐stage kidney disease requiring dialysis that could guide clinical decision making or further research in this area. The aim of this systematic review was, therefore, to assess the safety of metformin in dialysis patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Protocol and registration

This review was registered on PROSPERO: CRD42017081375.

2.2. Types of studies

Observational studies were included. No randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were found.

2.3. Participants

Studies were eligible if they evaluated metformin use in patients undergoing regular maintenance dialysis. Study selection was not restricted to patients with diabetes.

2.4. Intervention

All dosing regimens and formulations of metformin.

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the assessments of:

All‐cause mortality

Occurrence of lactic acidosis

New onset myocardial infarction (MI)

Secondary outcomes included other adverse events. Where available, information on the occurrence of fatal and/or nonfatal MI, fatal and/or nonfatal stroke, renal failure related mortality, revascularisation, time to event, quality of life and laboratory results (e.g. lactate concentration, pH, metformin concentration) were collected.

Long‐term use was defined as concomitant metformin and dialysis therapy for ≥12 months.

2.6. Electronic searches

MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library (inception to December 2018) were searched. The World Health Organisation clinical trials registry22 was also searched and reference lists of relevant RCTs and systematic reviews were screened for eligible studies.

2.7. Study selection

Three reviewers (C.A.S./J.C./G.G.) independently screened titles and abstracts and read potentially eligible full texts. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The search strategy (Table S1) did not impose language or date restrictions.

2.8. Data extraction and management

Three reviewers (C.A.S./J.C./G.G.) independently extracted study and patient characteristics, and outcomes data. Additionally, information on type and duration of dialysis, dose, formulation and duration of metformin therapy, concomitant therapy and safety monitoring (assessment of biochemical markers against universally accepted reference ranges) were extracted.

2.9. Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (C.A.S./J.C.) independently assessed the risk of bias of eligible studies using the Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS‐1) tool.23 Using this tool, each of the 7 items were rated high, moderate, serious or critical risk of bias. Observational studies that evaluated ≤10 participants were assigned critical risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

2.10. Reporting of outcomes

Mortality, the total number of patients experiencing a major cardiovascular event (CVE) or lactic acidosis (as a proportion of the total number of study patients), were reported.

2.11. Missing data

If relevant data were not provided, study authors were contacted.

2.12. Assessment of heterogeneity and reporting bias

Clinical heterogeneity was assessed by considering characteristics of the patients, intervention, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement. Results were considered separately in cases where it was not appropriate to pool data.

2.13. Data synthesis

Outcomes were based on whether the use of metformin was: (i) cautious, intentional; or (ii) inadvertent (metformin was not meant to be prescribed/consumed when starting dialysis). Safety parameters were considered separately for the 2 groups.

Mortality outcomes in the studies of cautious metformin use were compared to those in the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association [ERA‐EDTA] Registry,24 a database of 123 407 dialysis patients across 9 different countries. In the ERA‐EDTA, 35% of adults died in the first 3 years after commencement of dialysis.

2.14. Overall quality of evidence rating

We used GRADE (Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations)25 to evaluate the overall quality of evidence. For observational studies, the quality started as low and was downgraded a level for each of 4 factors:

limitation in study design (at least 1 study in an assessment was judged as moderate risk of bias or worse according to ROBINS‐126, 27);

inconsistency of results (arising from populations, interventions or outcomes);

imprecision (e.g. when the total sample size was <40028);

publication bias (assessed if there were ≥10 studies).

It was not necessary to assess for indirectness as this review encompassed a specific research question and population group.

3. RESULTS

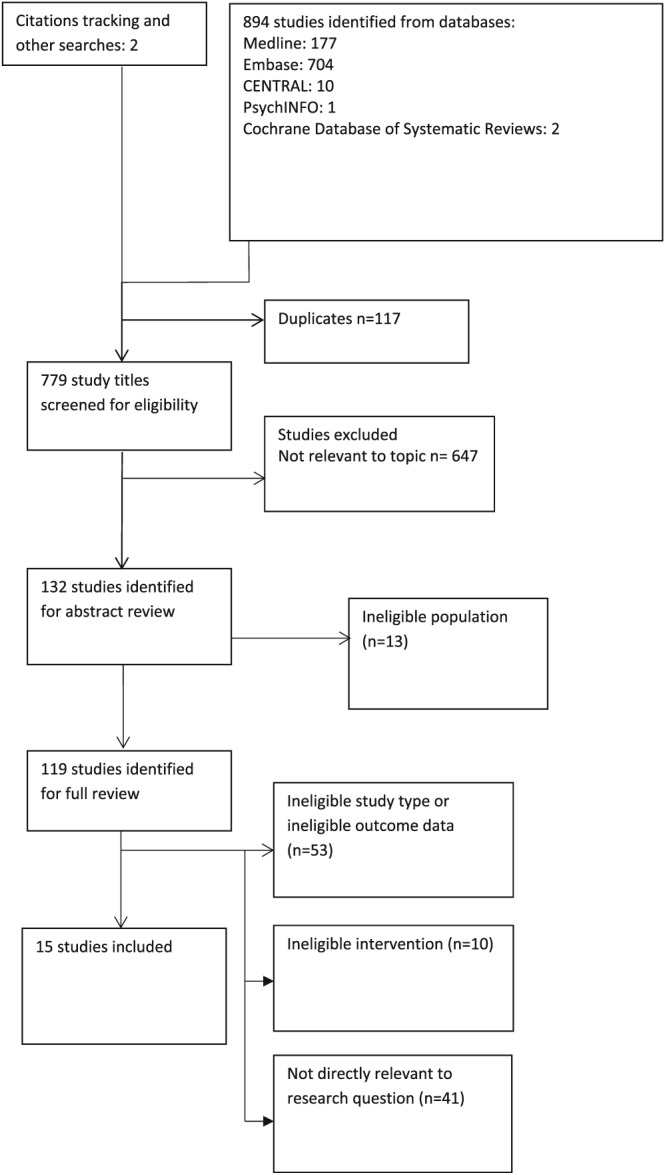

A total of 896 studies were screened, of which 15 studies12, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 were eligible (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2). Seven studies29, 30, 31, 32, 39, 41, 42 were prospective observational studies that reported on cautious metformin use in dialysis patients (Tables 1 and 2). However, only 339, 41, 42 (n = 179) provided long‐term follow‐up data. One retrospective case–control analysis40 reported on 243 metformin users on HD therapy.

Figure 1.

Summary of search strategy and outcome of trial inclusion and exclusion

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies evaluating cautious, intentional use of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis

| Study | Study type | Patient characteristics | Duration of dialysis † | Metformin dose/duration of study | Key outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acidosis | Mortality | Cardiovascular event | |||||

| Peritoneal dialysis | |||||||

|

Al‐Hwiesh et al., 201429 |

Prospective observational |

n = 35 Median age: 54 (IQR 47–59) 20 ♂ IDDM 18 y (IQR 14–21 y) |

31 m (IQR 27–36) prior to and over study period |

500–1000 mg d/ 12 mo |

Not present | None | None |

|

Al‐Hwiesh et al., 2017a30 |

Prospective observational |

n = 83 Mean age 53 ± 12.5 y 55 ♂ T2DM 13 ± 9.4 y |

27 ± 9.8 mo over study period |

500–1000 mg d/ 36 mo |

Not present | n = 6 ‡ |

3 MI 3 cerebral haemorrhage |

|

Duong et al., 201231 |

Prospective observational |

n = 1 ♂ Age 66 y |

12 mo |

250 mg d/ 6 wk |

Not present | None | None |

| Haemodialysis (HD) or haemodiafiltration (HDF) | |||||||

|

Al‐Hwiesh et al., 2017b41 |

Prospective observational |

n = 61 Mean age: 55 ± 11.8 y 38 ♂ T2DM 14 ± 7.8 y |

29 ± 8.1 mo over study period |

250–500 mg thrice weekly, postdialysis/36 m § | Not present | n = 4 ‡ |

1 cerebral haemorrhage 2 acute MI 1 pulmonary embolism |

| Day, 201742 | Prospective observational |

n = 7 (8 enrolled, data for 7) Mean age: 66 ± 6 y 7 ♂ T2DM 20.5 ± 10 y ¶ |

4.1 ± 3.5 y (HDF) |

250 mg, thrice weekly post‐HDF/ 2–12 wk |

Not present | n = 2 ‡ |

1 acute MI 1 suspected MI |

|

Duong et al., 201231 |

Prospective observational |

n = 1 ♂ Age: 64 y T2DM ~20 y |

12 m (peritoneal dialysis prior to HD) |

250 mg d/ 6 wk |

Not present | None | None |

|

Lalau et al., 198939 |

Prospective observational |

n = 2 (minimum other detail) Diabetes not reported |

Chronic (duration unknown) |

850 mg (single dose) |

Not reported | None | None |

|

Smith et al., 201632 |

Prospective observational |

n = 4 ♂ Mean age: 69 ± 8.3 y T2DM 18.3 ± 9.9 y |

5.3 ± 2.6 y (HDF) |

250–500 mg, thrice weekly post‐HDF/12 wk odds ratio 500 mg, thrice weekly then once weekly post‐HDF /12 wk |

Not present | None | None |

| Chien et al., 201740 | Retrospective case–control |

n = 243 metformin users in the cases. Cases and controls matched for age, sex and initial year of HD |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | None |

Ischaemic stroke odds ratio 1.64 (1.32–2.04) Haemorrhagic stroke OR 2.15 (1.51–3.07) |

Prior to beginning study medication regimen unless otherwise indicated

All deaths due to the major cardiovascular event reported.

For 6 patients, 1 reported long history. MI: myocardial infarction; IDDM: insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; IQR, interquartile range. In Al‐Hwiesh's studies, 1000 mg dose allowed for people with satisfactory biochemistry and urine output.

Metformin dosing withheld transiently in the event of acute illness. In the studies by Day, Smith and Al‐Hwiesh 2017b,41 metformin dosing was adjusted as needed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies evaluating inadvertent use of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis

| Study | Study type | Patient characteristics | Duration of dialysis † | Metformin dose/duration | Key outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acidosis | Mortality | Cardiovascular event | |||||

| Peritoneal dialysis | |||||||

| Almaleki et al., 201533 | Case report |

n = 1 ♂ Age: 83 y DM (unknown duration) |

3.5 y |

Unknown/ 1 wk |

Present | None | None |

| Gao et al., 201635 | Case report |

n = 1 ♂ Age: 66 y DM (unknown duration) |

~3 y | 500 mg thrice daily/3 d | Present | None | None |

| Khan et al., 199337 | Case report |

n = 1 ♀ Age: 76 y NIDDM (unknown duration) |

~2 y |

1000 mg d/ ~6 y |

Present | One | None |

| Schmidt et al., 199738 | Case report |

n = 1 ♀ Age: 62 y NIDDM (unknown duration) |

Not reported | 500 mg twice daily/1 mo | Present | None | None |

| Haemodialysis or haemodiafiltration | |||||||

| Altun et al., 201434 | Case report |

n = 1 ♂ Age: 76 y T2DM (unknown duration) |

3.5 y |

2000 mg daily/ 4 wk |

Present | None | None |

| Duong et al., 201312 | Case report |

n = 1 ♀ Age: 69 y |

Unknown |

1000 mg daily/ 4 wk |

Present | None | None |

| Kang et al., 201336 | Case report |

n = 2 69 y ♂; 55 y ♀ DM (unknown or 20‐y duration) |

4–5 y |

1000 mg daily/ 5 or 6 wk |

Not reported | None | Metformin‐associated encephalopathy |

| Lalau et al., 198939 | Case report | n = 2 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | None | Not reported |

Prior to hospitalisation/admission. NIDDM: noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus; DM: diabetes mellitus.

Eight studies12, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 reported on inadvertent use of metformin among 10 patients. No eligible RCTs were identified.

3.1. Risk of bias

Twelve12, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 42 of the 15 eligible studies were deemed to have critical risk of bias (Table 3). Three studies29, 30, 41 were considered to have moderate risk of bias (Table 3). Potential confounders, such as duration of dialysis at baseline, were not consistently reported by these studies, or accounted for in the analysis. Furthermore, participant selection was often based on convenience sampling.

Table 3.

Risk of bias in studies on the use of metformin in haemodialysis

| Author, year | Bias due to confounding | Bias in selection of patients into the study | Bias in classification of interventions | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing data | Bias in measurement of outcomes | Bias in selection of the reported result | Overall risk* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al‐Hwiesh et al., 201429 | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Al‐Hwiesh et al., 2017a30 | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Al‐Hwiesh et al., 2017b41 | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Chien et al., 201740 | Critical risk | Serious risk | NA | NA | Critical risk | Serious risk | Critical risk | Critical risk |

A study was assigned moderate risk if the study was judged to be at low or moderate risk for all domains. A study was assigned critical risk if 1 or more of domains was rated as critical risk. In these studies, patients were prevalent users of dialysis therapy.

3.2. Metformin and dialysis treatment regimens

3.3. Cautious, intentional use

Details on metformin use were reported in 7 studies29, 30, 31, 32, 39, 41, 42 (n = 194). Use ranged from 1 day to 36 months in predominantly middle‐aged or older patients with comorbid diabetes mellitus who were receiving PD, HD or haemodiafiltration (HDF; Table 1). Metformin dosing regimens varied and there was limited information on formulation. A maximum dose of 1000 mg/d was administered in 2 studies29, 30 in patients with a creatinine clearance ≥10 mL/min and urine output ≥1000 mL/d. Metformin concentrations were elevated (>5 mg/L) in 4.4% of samples collected in 1 study,29 while 2 other studies reported metformin concentrations ≥10 mg/L in 17 and 16% of patients, respectively.30, 41 The mean ± standard deviation metformin concentration achieved in patients over the course of these 3 studies was 2.6 ± 1.5, 5.2 ± 4.3 and 5.3 ± 3.3 mg/L, respectively.29, 30, 41

3.4. Inadvertent use

Eight case studies12, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 (n = 10) reported on the inadvertent daily dosing of metformin over 3 days to ~2 years concomitantly with HD or PD (Table 2). The studies reported emergency department presentations of 4 males (age range 62–83 y) and 4 females (age range 55–76 y) with comorbid diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease. Minimal patient‐specific information was available for the 2 remaining patients.39

Metformin plasma concentrations at presentation were provided for 3 patients, each exceeding the reported safety threshold of 10 mg/L12, 33, 35 In 1 report, initiation of metformin therapy was self‐directed, provoked by pain associated with insulin injections.35 In another report, the patient's therapy was switched from insulin to metformin by his family (in the absence of medical advice) following an episode of hypoglycaemia.33 Patient specific information, including relevant biochemistry, is provided in Tables S2 and S3.

3.5. All‐cause mortality

3.6. Cautious, intentional use

Three studies30, 41, 42 reported on 12 deaths, 6 in patients on PD,30 4 in patients on HD41 and 2 in patients on HDF42 (Table 1). Two of these studies provided long‐term follow‐up data.30, 41 One study30 (n = 83) reported 6 deaths (~7%) within the 3‐year study period (Tables 1 and 2) in patients undergoing automated PD. Another study41 undertaken by the same group (n = 61) reported 4 deaths (~7%) within the 3‐year study period in patients undergoing HD. These figures are smaller than those reported in the ERA‐EDTA registry, but the evidence for both findings is very low quality (downgraded for imprecision and risk of bias). The third study by this group29 (n = 35) reported no deaths within the 1‐year study period among patients undergoing PD.

One study (n = 7) reported 2 deaths (29%) within the 12‐week treatment period among patients undergoing HDF.42 Of note, patients in this study42 had been on dialysis for a mean duration of 4.1 years at baseline. The study was halted before completion.

3.7. Inadvertent use

One death was reported in 1 study of inadvertent metformin use during PD.12 The patient (female, 76 y) had received metformin therapy (1000 mg/d) for a total of ~6 years (dosage presumed to be unchanged for that period) and was undergoing ambulatory PD (concomitantly with metformin therapy) for the past 2 years. The patient presented with lactic acidosis that was refractory to emergency treatment.

3.8. Myocardial infarction

3.9. Cautious, intentional use

All deaths reported were due to major CVE (Table 1). In total there were 6 cases of acute MI (3/83,30 2/61,41 1/742). Unpublished information indicates that 1 death (1/7)42 was due to suspected MI.

3.10. Inadvertent use

There were no reported cases of nonfatal CVE or MI in studies reporting inadvertent metformin use.

3.11. Occurrence of lactic acidosis

3.12. Cautious, intentional use

Lactate concentrations were provided in 6 studies of cautious use,29, 30, 31, 32, 41, 42 whereas only 3 of these studies29, 30, 41 provided data on both lactate and pH. No study reported the occurrence of lactic acidosis; however, the evidence for these findings was very low quality. Blood lactate concentrations of 2–5 mmol/L (described as hyperlactaemia by study authors and other sources43) was reported in ~1%,29 14%30 and 16%41 of total blood samples taken over the course of 3 long‐term studies. No correlation between plasma lactate and metformin concentrations was reported. Age was a predictor of hyperlactaemia in 1 study (risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval 0.21–0.76), with those aged ≥60 years more likely to be affected.30 Similarly, there were no reported cases of lactic acidosis in the studies evaluating intentional metformin use.

3.13. Inadvertent use

Lactate concentration and/or pH were reported in 6 studies of 6 patients12, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38 and lactic acidosis was diagnosed for all 6 patients. Lactate concentrations ranged from 7 to 28 mmol/L on presentation. Three patients had lactic acidosis in the presence of elevated metformin concentrations (2020 mg/L,33 190 mg/L35 and 39.2 mg/L,12 respectively). A further 2 studies did not provide sufficient data to make a determination about lactic acidosis.36, 39 Symptoms at hospital admission included gastrointestinal disturbance (vomiting and/or diarrhoea), nausea, anorexia, epigastric pain, reduced consciousness or drowsiness, increased heart rate and acidotic breath. Emergency dialysis treatment successfully reversed the symptoms for all but 1 patient who died.

3.14. Other outcomes—quality of life, nonfatal cardiovascular events

Quality of life outcomes were not reported. There were no deaths attributed to dialysis complications. However, 1 retrospective case–control analysis40 reported higher risks of ischaemic (odds ratio 1.64 [1.32–2.04]) or haemorrhagic (odds ratio 2.15 [1.51–3.07]) stroke among metformin users undergoing HD compared to patients undergoing HD but not taking metformin.

3.15. Glycaemic control

All studies of cautious use, except 1,39 reported markers of glycaemic control (Tables S2 and S3), primarily HbA1c. Additional markers of glycaemic control collected were serum fructosamine31, 32, 42 and fasting and random blood glucose.29, 30, 32, 42 Whilst some studies reported mean improvements in HbA1c by the end of the study (compared with baseline),29, 30, 32, 41 it is unclear if this was attributed to metformin use as patients were often also receiving insulin.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Statement of principal findings

The evidence regarding metformin safety in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis is inconclusive. Two small observational studies showed that metformin (≤1000 mg/d for up to 12 or 36 mo) was not associated with lactic acidosis and did not result in adverse mortality outcomes in the long‐term for patients with comorbid diabetes mellitus undergoing automated PD. There is conflicting evidence regarding metformin use in HD. One prospective study showed thrice weekly dosing of metformin (250–500 mg for up to 36 mo) did not result in adverse mortality outcomes or lactic acidosis. Conversely, a retrospective analysis showed that metformin was associated with increased risk of stroke in patients undergoing HD. All the findings are based on very low‐quality evidence reflecting the small size and nature of the studies. Lactic acidosis was a common occurrence in cases of inadvertent metformin use, eventuating in 1 death. No RCT evidence was identified.

4.2. Strengths and weaknesses of this review

This is the first systematic review evaluating metformin safety in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis. It provides valuable information to guide the discussion around metformin dosing regimens, duration of treatment and patient outcomes across the principal dialysis modalities. It was not possible to pool data as there was heterogeneity between studies with respect to dosing regimens, duration of metformin treatment, and reporting of lactate and metformin concentrations. Furthermore, the studies were small observational studies with moderate or critical risk of bias.

4.3. Strengths and weaknesses of the study in relation to other studies

Previous studies have evaluated metformin use in patients with varying stages of CKD, but did not report on dialysis patients.19, 20 These studies provide mixed evidence, with 1 recent review20 showing that metformin improved clinical outcomes (including all‐cause mortality) in patients with CKD. Conversely, a large population‐based cohort study showed that metformin use in patients with advanced CKD was associated with higher mortality risk, although this appeared to be dose‐dependent and increased with doses >1000 mg/d.19 We did not identify any published reports of cautious use involving doses >1000 mg/d in dialysis patients. However, doses ≤1000 mg have been evaluated.29, 30

4.4. Meaning of the study, implications for clinicians, researchers and policy makers

The current evidence regarding metformin safety in dialysis patients is inconclusive, and cannot be used to strongly support or dismiss its use in this context. In studies where metformin concentrations and safety parameters were closely monitored, there was no evidence of an increased risk of lactic acidosis or death. However, these studies had important limitations, namely small sample size and lack of controls. An adequately powered, placebo‐controlled RCT is needed to provide more definitive evidence. The finding that metformin is associated with greater risk of stroke in patients undergoing HD was obtained from the Taiwan National Research Institute and is surprising given that data from the same source indicated that nondialysed patients taking metformin had a lower risk of stroke (hazard ratio 0.47; 95% confidence interval 0.42–0.52).44 Furthermore, only a small proportion of cases in the included case–control analysis40 were considered metformin users—defined as receiving a metformin prescription within 1 year of incident stroke (n = 68/545 [~12%] among haemorrhagic stroke cases and 175/1353 [~13%] among ischaemic stroke cases). There was no information on dose and duration of metformin therapy prior to or during dialysis and no evidence of therapeutic drug monitoring of metformin. In general, these findings conflict with the other studies that were identified.

Diabetes is the most common cause of end‐stage kidney disease, accounting for ~45% of cases,45, 46, 47, 48, 49 and unsurprisingly the majority of patients identified in this study had co‐morbid diabetes mellitus. In dialysis patients, cardiovascular mortality is the main cause of death (up to 20 times greater than in the general population).24 Furthermore, dialysis patients sustaining an acute MI suffer poor long‐term survival, with a 2‐year mortality of ~74%.50

This review identified 1 death associated with lactic acidosis and this was the result of inadvertent, unmonitored use of metformin alongside dialysis therapy for ~2 years.37 Ten deaths were identified in patients receiving cautious, intentional metformin therapy alongside long‐term dialysis (up to 3 years).30, 41 These patients were predominantly middle‐aged, with diabetes mellitus and all the deaths were attributed to CVE. These figures are smaller than all‐cause mortality rates (35%) in the ERA‐EDTA registry,24 as well as renal registries in the Asia Pacific46 and North America.47 Whilst 3 studies were carried out in the Middle East,29, 30, 41 a country‐specific consideration of these figures was not possible as mortality has not been reported in renal registries in the Middle East.51 However, the present findings, along with the report of only 1 fatal case of lactic acidosis, provide some weight to suggestions that metformin could be used safely in patients undergoing dialysis.

Current clinical practice guidelines caution against metformin use in dialysis patients, due to the lack of evidence around safety. As metformin is eliminated by the kidneys, the potential for metformin accumulation in patients with reduced kidney function provokes concern that lactic acidosis will develop. However, the spectre of lactic acidosis is largely historical.52 As was identified in this review, studies regularly fail to find a correlation between metformin and lactate concentrations.29, 30, 41 Regardless, 1 antidote to such concerns is that cautious metformin therapy in dialysis patients must be closely monitored to optimise patient safety outcomes.53, 54 Repeated measures of metformin and lactate concentrations, in addition to related biochemical markers, was consistent across all but 1 study of cautious metformin dosing.39 While it is acknowledged that the evidence for the reported safety threshold for metformin concentrations is unclear, monitoring of metformin alongside biochemical markers of lactic acidosis provides prescribers with the information to adjust metformin therapy in light of impaired renal function. In contrast, a key weakness common to studies reporting on inadvertent use of metformin was the lack of monitoring of metformin therapy. Furthermore, a concerning pattern identified in these case studies was the presentation of patients to the emergency department following initiation of dialysis without reduction of metformin dosing to accommodate the patient's reduced renal function.36

4.5. Directions for future research

There has been growing interest in the cardiovascular benefits of metformin and large studies such as the placebo‐controlled GLINT trial (glucose lowering in nondiabetic hyperglycaemia) are underway to evaluate the risk reduction in cardiovascular outcomes using metformin.55 However, in order to propose the use of this drug in patients undergoing dialysis due to possible favourable impacts on long‐term clinical outcomes, much stronger evidence than is available currently is needed to assure safety in this group.

Our review highlights the need for a large definitive RCT to determine the safety of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis. For patients undergoing HD, the most common dialysis modality in countries such as the USA,47 250–500 mg thrice weekly postdialysis sessions has been used. In PD, 500–1000 mg/d has been used. Given the variability in safety monitoring between studies, future studies would provide better data regarding safety margins for metformin concentrations and biochemical indices.

5. CONCLUSION

There is inconclusive evidence regarding the safety of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis. Further research employing large RCTs comparing metformin to placebo are needed to resolve this uncertainty.

COMPETING INTERESTS

J.C., S.S., F.S., G.G., K.W., T.F., J.G. and R.D. have been involved in clinical trial research evaluating the use of metformin in dialysis patients.

CONTRIBUTORS

All authors contributed to the inception, design of the study and writing the manuscript. Additionally, C.A.S., J.E.C., G.G. were involved in screening and selection of eligible studies and data analysis. C.A.S. and J.E.C. carried out risk of bias assessments.

Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work.

Supporting information

Table S1 Summary of search strategy (a broad search strategy using only the patient group (patients on dialysis) and the intervention (metformin) i.e. the P and I in the PICO was used to capture as many studies that might be eligible as possible.

Table S2: Characteristics of metformin dosing and biochemistry monitoring and major co‐morbidities in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis

Table S3: Characteristics of metformin dosing and biochemistry monitoring and major co‐morbidities in patients undergoing haemodialysis

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by funding from Diabetes Australia Research Trust General Grant. C.A.S. is supported by an early career development fellowship from the University of Sydney.

Abdel Shaheed C, Carland JE, Graham GG, et al. Is the use of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis hazardous for life? A systematic review of the safety of metformin in patients undergoing dialysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2772–2783. 10.1111/bcp.14107

Registration: CRD42017081375.

*Christina Abdel Shaheed and Jane E. Carland contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):193‐203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(6):540‐559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey CJ, Grant PJ. The UK prospective diabetes study. Lancet. 1998;352(9144):1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nesti L, Natali A. Metformin effects on the heart and the cardiovascular system: a review of experimental and clinical data. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases: NMCD. 2017;27(8):657‐669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bolen S, Feldman L, Vassy J, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and safety of oral medications for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(6):386‐399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Albright A. The National Diabetes Prevention Program: from research to reality. Diabetes Care Educ Newsl. 2012;33(4):4‐4):7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johansen K. Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of NIDDM. Meta‐analysis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(1):33‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dujic T, Zhou K, Donnelly LA, Tavendale R, Palmer CN, Pearson ER. Association of Organic Cation Transporter 1 with intolerance to metformin in type 2 diabetes: a GoDARTS study. Diabetes. 2015;64(5):1786‐1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luft D, Deichsel G, Schmulling RM, Stein W, Eggstein M. Definition of clinically relevant lactic acidosis in patients with internal diseases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;80(4):484‐489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kajbaf F, Lalau JD. Mortality rate in so‐called "metformin‐associated lactic acidosis": a review of the data since the 1960s. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(11):1123‐1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tucker GT, Casey C, Phillips PJ, Connor H, Ward JD, Woods HF. Metformin kinetics in healthy subjects and in patients with diabetes mellitus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;12(2):235‐246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duong JK, Furlong TJ, Roberts DM, et al. The role of metformin in metformin‐associated lactic acidosis (MALA): case series and formulation of a model of pathogenesis. Drug Saf. 2013;36(9):733‐746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heaf J. Metformin in chronic kidney disease: time for a rethink. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34(4):353‐357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Type 2 Diabetes in adults: management. In NICE Guideline (NG28), 2015. [PubMed]

- 15. FDA . FDA drug safety communication: FDA revises warnings regarding use of the diabetes medicine metformin in certain patients with reduced kidney function. Food and Drug Administration, 2016.

- 16. Stades AM, Heikens JT, Erkelens DW, Holleman F, Hoekstra JB. Metformin and lactic acidosis: cause or coincidence? A review of case reports. J Intern Med. 2004;255(2):179‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lalau JD, Lemaire‐Hurtel AS, Lacroix C. Establishment of a database of metformin plasma concentrations and erythrocyte levels in normal and emergency situations. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31(6):435‐438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeFronzo R, Fleming GA, Chen K, Bicsak TA. Metformin‐associated lactic acidosis: current perspectives on causes and risk. Metabolism. 2016;65(2):20‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hung SC, Chang YK, Liu JS, et al. Metformin use and mortality in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: national, retrospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(8):605‐614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crowley MJ, Diamantidis CJ, McDuffie JR, et al. Clinical outcomes of metformin use in populations with chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, or chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(3):191‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richards S. Metformin and patients on dialysis. Aust Prescr. 2016;39(3):74‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organisation (WHO) . International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Available from: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ .

- 23. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Jager DJ, Grootendorst DC, Jager KJ, et al. Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality among patients starting dialysis. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1782‐1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. (eds). GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from https://guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook .

- 26. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence‐‐study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):407‐415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(oct18 2):d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence‐‐imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1283‐1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Al‐Hwiesh AK, Abdul‐Rahman IS, El‐Deen MAN, et al. Metformin in peritoneal dialysis: a pilot experience. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34(4):368‐375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Al‐Hwiesh AK, Abdul‐Rahman IS, Noor AS, et al. The phantom of metformin‐induced lactic acidosis in end‐stage renal disease patients: time to reconsider with peritoneal dialysis treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2017;37(1):56‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duong JK, Roberts DM, Furlong TJ, et al. Metformin therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):963‐965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith FC, Kumar SS, Furlong TJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of metformin in patients receiving regular Hemodiafiltration. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(6):990‐992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Almaleki N, Ashraf M, Hussein MM, Mohiuddin SA. Metformin‐associated lactic acidosis in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26(2):325‐328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altun E, Kaya B, Paydas S, Sariakcali B, Karayaylali I. Lactic acidosis induced by metformin in a chronic hemodialysis patient with diabetes mellitus type 2. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(2):529‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gao J, Gu Z, Xu Y, Na Y. Peritoneal dialysis treatment of metformin‐associated lactic acidosis in a diabetic nephropathy patient. Clin Nephrol. 2016;86(11);279‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kang YJ, Bae EJ, Seo JW, et al. Two additional cases of metformin‐associated encephalopathy in patients with end‐stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2013;17(1):111‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khan IH, Catto GRD, MacLeod AM. Severe lactic acidosis in patient receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. BMJ. 1993;307(6911):1056‐1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidt R, Horn E, Richards J, Stamatakis M. Survival after metformin‐associated lactic acidosis in peritoneal dialysis‐‐dependent renal failure. Am J Med. 1997;102(5):486‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lalau JD, Andrejak M, Moriniere P, et al. Hemodialysis in the treatment of lactic acidosis in diabetics treated by metformin: a study of metformin elimination. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1989;27(6):285‐288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chien LN, Chou CL, Chen HH, et al. Association between stroke risk and metformin use in hemodialysis patients with diabetes mellitus: a nested case‐control study. J am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al‐Hwiesh AK, Abdul‐Rahman IS, El‐Salamony T, et al. Safety of metformin in diabetic hemodialysis patients between fact and fiction: a multi center observational study. Int J Sci Res. 2017;6(12):463‐467. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Day R. Addendum regarding “pharmacokinetics of metformin in patients receiving regular Hemodiafiltration”. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(6):870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marichev A. ASSA13‐08‐11 how oxygen delivery affects on the development of hyperlactatemia and lactic acidosis. Heart. 2013;99(Suppl 1):A39‐A39. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheng YY, Leu HB, Chen TJ, et al. Metformin‐inclusive therapy reduces the risk of stroke in patients with diabetes: a 4‐year follow‐up study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(2):e99‐e105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chapter 3. 2014 ANZDATA registry 37th Annual report. Survival on renal replacement therapy. Available from: https://wwwgooglecom/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=2ahUKEwibnuiW9ejcAhXHQd4KHZm_Am0QFjADegQIBhAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwwwanzdataorgau%2Fanzdata%2FAnzdataReport%2F37thReport%2Fc03_deaths_v30_20150313pdf&usg=AOvVaw07mpvroZsurRQzL7PboCFX .

- 46. Ritz E, Rychlik I, Locatelli F, Halimi S. End‐stage renal failure in type 2 diabetes: a medical catastrophe of worldwide dimensions. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34(5):795‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, et al. Excerpts from the US renal data system 2009 annual data report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(1 Suppl 1):S1‐S420. a6‐7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Atkins RC. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;67(94):S14‐S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lim WH, Johnson DW, Hawley C, et al. Type 2 diabetes in patients with end‐stage kidney disease: influence on cardiovascular disease‐related mortality risk. MJA. 2018;209(10):440‐446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Herzog CA. Cardiac arrest in dialysis patients: approaches to alter an abysmal outcome. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;63(84):S197‐S200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu FX, Rutherford P, Smoyer‐Tomic K, Prichard S, Laplante S. A global overview of renal registries: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Assan R, Heuclin C, Girard JR, LeMaire F, Attali JR. Phenformin‐induced lactic acidosis in diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1975;24(9):791‐800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bodmer M, Meier C, Krahenbuhl S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Metformin, sulfonylureas, or other antidiabetes drugs and the risk of lactic acidosis or hypoglycemia: a nested case‐control analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2086‐2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):Cd002967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Griffin SJ, Bethel MA, Holman RR, et al. Metformin in non‐diabetic hyperglycaemia: the GLINT feasibility RCT. Health Technol Asses. 2018;22(18):1‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Summary of search strategy (a broad search strategy using only the patient group (patients on dialysis) and the intervention (metformin) i.e. the P and I in the PICO was used to capture as many studies that might be eligible as possible.

Table S2: Characteristics of metformin dosing and biochemistry monitoring and major co‐morbidities in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis

Table S3: Characteristics of metformin dosing and biochemistry monitoring and major co‐morbidities in patients undergoing haemodialysis

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.