Abstract

Thiazide diuretics have been the cornerstone of hypertension treatment for >5 decades. Most recent European and American guidelines recommend both thiazide‐type and thiazide‐like diuretics as first‐line drugs for all patients with hypertension. In contrast, diuretics are not regarded as first‐line treatment in the UK and in patients who are to be initiated on a diuretic treatment, thiazide‐like molecules, such as chlortalidone and indapamide are the preferred option. This review examines the prescribing trend of the 4 most commonly prescribed thiazide diuretics for the treatment of hypertension in the UK. Prescription cost analysis data were obtained for both 2010 and 2016/2017 for each region of the UK to analyse the impact of the 2011 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence hypertension guidelines on the trend in thiazide diuretic prescribing. Overall, the prescriptions of thiazide diuretics declined over the years. Bendroflumethiazide is the most commonly prescribed diuretic in the UK and despite some geographical differences, thiazide‐type diuretics are more widely used than thiazide‐like. The use of indapamide increased significantly between 2010 and 2016/2017 while chlortalidone was rarely employed. Of the many factors affecting trends in prescriptions, clinical inertia, treatment adherence, availability of the products and the lack of fixed dose combinations may play a role.

Keywords: diuretic, hypertension, prescribing, thiazide

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) disease, stroke and renal failure.1 It is estimated that the global prevalence of hypertension was 1.13 billion in 2015 with over 150 million individuals affected in central and eastern Europe.2 It is estimated that approximately 24% of the general population3 in England have either general practitioner‐recorded or undiagnosed hypertension and antihypertensive drugs are the most commonly used medicine by adults living in their own homes.4 Several guidelines have been developed worldwide for the management of hypertension, and these serve as reference standards for clinical practitioners. Thiazides are among the most frequently used antihypertensive agents in the USA and western Europe, accounting for approximately 30% of prescriptions5 with an increasing trend. In the USA, there was a 1.7‐fold increase from 1999 through 2012 in thiazide prescriptions.2 Large meta‐analyses have confirmed their efficacy as blood pressure (BP)‐lowering and CV disease prevention agents.6

According to their molecular structure, thiazide diuretics can be divided into thiazide‐type and thiazide‐like, which differ in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile (Table S1 ). Thiazide‐type diuretics include https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=7122 (BDTZ) and https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=4836 (HCTZ) while other drugs with a similar pharmacological action but a different chemical structure, such as https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=7203 (INDA) and https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=7147 (CLTD), are termed thiazide‐like diuretics. Thiazide‐type diuretics achieve their diuretic action via inhibition of the Na+/Cl− cotransporter in the renal distal convoluted tubule.7 Thiazide‐like diuretics act a more proximal segment of the convoluted tubule and some molecules such as INDA also have vasodilator actions.8, 9 The use of thiazide diuretics has been associated with electrolyte disorders, in particular hypokalaemia, and adverse metabolic actions, such as hyperuricaemia and impaired glucose tolerance; however, it is well recognized that thiazide‐induced effects on plasma glucose, lipids, and lipoproteins are dose‐dependent and can be minimized by using lower doses.10

Most recent European and American guidelines continue to recommend thiazide diuretics as first‐line drugs for all patients with hypertension (Table 1). In contrast, diuretics are not regarded as first‐line treatment in the UK and thiazide‐like molecules, such as CLTD or INDA are the preferred option in patients who are to be started on diuretics. This review focuses on 4 most commonly prescribed thiazide diuretics in the UK—BDTZ, HCTZ, INDA and CLTD.

Table 1.

Role of thiazide diuretics in the treatment of hypertension according to guidelines of different regions, including suggested first‐line treatments and alternative options

| Region | Diuretic first‐line treatment | Suggested diuretics | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe (2018)11 | Yes | Thiazide‐type/thiazide‐like diuretics |

Loop diuretics if eGFR <30 mL/min Spironolactone in patients with resistant hypertension |

| USA (2017)12 | Yes | Thiazide‐type/thiazide‐like diuretics: CLTD is preferred based on prolonged half‐life and proven trial reduction of cardiovascular disease |

Loop diuretic in patients with heart failure or eGFR <30 mL/min Combination therapy of potassium‐sparing diuretic with thiazide diuretics in patients with hypokalaemia on thiazide monotherapy Spironolactone or eplerenone in primary aldosteronism and resistant hypertension |

| Canada (2018)13 | Yes | Thiazide‐type/thiazide‐like diuretic, with longer‐acting diuretics preferred |

Loop diuretic can be considered in hypertensive chronic kidney disease patients with extracellular fluid volume overload. In patients with heart failure, aldosterone antagonists (mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) may be added for patients with a recent cardiovascular hospitalization, acute myocardial infarction, elevated BNP or NT‐proBNP level, or NYHA class II to IV symptoms. Loop diuretic as additive therapy. |

| UK (2011)14 | No | Thiazide‐like diuretic, such as CLTD or INDA in preference to a conventional thiazide diuretic. |

For patients already on BDTZ or HCTZ and whose BP is stable and well controlled, continue treatment. If a first‐line treatment with a CCB is not suitable or if there is evidence of heart failure or a high risk of heart failure, offer a thiazide‐like diuretic. Resistant hypertension—consider adding low‐dose spironolactone if K+ ≤ 4.5 mmol/L or higher‐dose thiazide‐like if >4.5 mmol/L. |

BDTZ, Bendroflumethiazide; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; INDA, indapamide; CLTD, chlorthalidone; CCB, calcium channel blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BP, blood pressure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide

1.1. HCTZ

HCTZ is a thiazide‐type diuretic often combined with other agents in the treatment of hypertension. The European Union lists almost 20 combination products containing HCTZ and at least 1 other drug, although not all are currently in use.15 In the UK, HCTZ is only available in combination with other antihypertensives (one or 2 other agents) and is generally used at the dose of 12.5 or 25 mg daily.

At the dose commonly prescribed in clinical practice, HCTZ is less effective in reducing ambulatory BP compared to other antihypertensives, including angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and calcium channel blockers (CCBs; reduction in 24 h systolic BP of 6.5 mmHg for HCTZ compared to 12.9 mmHg for ACE inhibitors (P < .003) and 11.0 mmHg for CCBs (P < .05).16 In contrast, higher doses (>50 mg and above) have similar efficacy to most other drug classes, although biochemical adverse effects, particularly hypokalaemia, limit its use.17

The efficacy of HCTZ compared to other thiazide diuretics has been extensively evaluated. A meta‐analysis from Ernst et al. showed that HCTZ was less effective than CLTD at reducing systolic BP (−23 ± 6.7 mmHg vs −17 ± 5.6 mmHg).18 This is in line with other findings that suggest CTLD is between 1.5 and 2 times as potent as HCTZ.19 Inferiority of HCTZ to INDA20 and BDTZ21 has also been highlighted in previous meta‐analyses and will be discussed in more details in the following sections. Multiple studies have documented that HCTZ has <24 h duration of action22 and the drug was administered twice daily in early trials. Of note, outcome evidence for low‐doses of HCTZ (12.5–25 mg) is lacking and no placebo‐controlled trial has ever tested the efficacy of HCTZ by itself in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). In a small unblinded trial conducted in the 1970s, HCTZ reduced the risk of stroke but not coronary artery disease.23 HCTZ appears to be less effective in preventing MACE compared to ACE (including all cardiovascular events or death from any cause (hazard ratio 0.89 [0.79–1.00] between ACE v diuretic group, P = .05) and myocardial infarction (hazard ratio 0.68 [0.47–0.98], P = .04).24 In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) considering soft outcomes, the addition of HCTZ to quinapril was inferior to INDA (added to quinapril) in improving ventricular function (measured with https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/tissue-doppler-imaging and https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/speckle-tracking-echocardiography) as well as vascular and endothelial function in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes.25 All these changes were independent of the changes in BP (systolic or diastolic).

Regarding side effects, HCTZ has been associated with a lower incidence of electrolytes abnormalities compared to BDTZ and CLTD. A population‐based case–control study within the Dutch Integrated Primary Care Information database found the risk of hyponatraemia to be greater with CLTD compared to HCTZ equivalent daily doses of 12.5 mg and 25 mg (Adjusted OR 2.09 [1.13–3.88] for 12.5 mg and 1.72 [1.15–2.57] for 25 mg).26 Furthermore, a meta‐analysis of dose–response relationships of HCTZ, BDTZ and CLTD conducted in 4683 subjects in over 53 comparison arms found that the potency series was BDTZ > CLTD > HCTZ and to reduce serum potassium by 0.4 mmol/L, the doses needed were 4.2, 11.9 and 40.5 mg, respectively.21

Although the risk of developing hyperuricaemia was lower in patients treated with HCTZ compared to CTLD,21 the risk of symptomatic gout was not.27 HCTZ similarly to other thiazides may increase the incidence of new‐onset diabetes.28 Although low doses of HCTZ (12.5–25 mg/d) have been shown to have adverse effects on fasting glucose and lipid profiles, the magnitude of these effects is modest.29 There is evidence that potassium may play a role in the development of these metabolic alteration and a recent study has shown that the adverse effect of HCTZ on glucose metabolism can be reduced by the concomitant use of a potassium‐sparing diuretic.30

HCTZ by contrast to other thiazides is classified as a possible carcinogenic drug by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (group 2B, possibly carcinogenic to humans).31 A recent series of articles from various Danish nationwide demographic and health registries have associated HCTZ use with increased risk of lip and skin cancer32, 33, 34, 35 whist use of other diuretics, including thiazide‐type (BDTZ) and thiazide‐like (INDA), were not. Following those publications, the British and Irish Hypertension Society has released a statement on the topic,36 which suggests caution in the interpretation of the data. In fact, conclusions derived by observational data can be affected by several potential methodological limitations.37

1.2. BDTZ

BDTZ is a thiazide‐type diuretic widely used in the UK. However, despite its widespread use, there is less evidence on its efficacy to lower BP and reduce MACE compared to other diuretics.38 In the UK, it is usually prescribed at the dose of 2.5 mg once daily for the treatment of hypertension, but there is also a single fixed combination with timolol listed in the British National Formulary.

A meta‐analysis based on the dose response between thiazide‐type and thiazide‐like diuretics showed that the estimated dose predicted to reduce systolic BP (SBP) by 10 mmHg was 1.4 mg for BDTZ compared to 26.4 mg for HCTZ.21 BDTZ was indeed the most powerful diuretic even when compared to CLTD, although the analysis included only 1 RCT with BDTZ (compared to 3 with CLTD and 22 HCTZ). In terms of adverse metabolic actions, a clear dose‐related effect has been shown for potassium, urate, glucose and cholesterol with low dose (1.25 mg daily) increasing only urate concentrations, whereas higher dose (10 mg daily) affect all the above biochemical variables.10 Of note, all doses of BDTZ have been found to reduce BP to a similar degree. In a small double blind, placebo‐controlled, crossover study, a daily dose of BDTZ 1.25 mg showed efficacy in lowering 24‐h ambulatory BP by 11/7 mmHg with no clinically significant effects on potassium and urate.39 A multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, parallel group comparison of nifedipine GITS 20 mg once daily and BDTZ 2.5 mg once daily showed similar efficacy in BP reduction in patients with mild‐to‐moderate hypertension.40 A recent systematic review41 based on the noninferiority of BDTZ on MACE reduction compared to INDA included only 2 trials with BDTZ performed in the UK, in which the dose of BDTZ was either nonspecified or 10 mg daily.

1.3. INDA

INDA is a thiazide‐like agent commonly prescribed in the UK at the dose of 2.5 mg as immediate‐release formulation or 1.5 mg daily as modified release. It is also available as a fixed dose combination with perindopril arginine 5 mg.

INDA acts as a diuretic but also as a direct vasodilator, via a calcium‐antagonist‐like vasorelaxant effect.8, 9 In a head‐to‐head meta‐analysis of 10 RCTs contrasting INDA with HCTZ,20 INDA lowered systolic BP by 54% more than HCTZ without evidence for greater adverse effects. The duration of antihypertensive action for INDA is estimated to be >24 hours for the immediate release formulation, and >32 hours for the modified released formulation.42 None of the studies included in the meta‐analysis of Roush et al.20 included MACE as outcome, but for surrogate endpoints such as left ventricular hypertrophy an additional benefit of INDA compared to HCTZ was seen in a small sample of hypertensive subjects.43 The efficacy of INDA on left ventricular mass regression was also tested in a larger trial against ACE,44 which found that INDA SR 1.5 mg had greater effect on LVMI reduction compared to Enalapril 20 mg despite a similar BP lowering effect. At renal level, there is also evidence that INDA has similar efficacy to ACE in reducing microalbuminuria45 in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes.

Focusing on MACE prevention, the efficacy of INDA has been tested in RCTs in patients with diabetes, the elderly and following stroke.46, 47, 48, 49 INDA has been associated with fewer adverse metabolic effects compared to other thiazides with a similar reduction in potassium level as HCTZ.20

1.4. CTLD

CTLD is a thiazide‐like diuretic available in the UK at the dose of 50 mg and as a fixed dose combination with atenolol and triamterene. Its distribution in red blood cells creates a reservoir, which may explain the long duration of action (> 48 h).

CTLD is a more powerful antihypertensive agent compared to HCTZ20 with a decrease in systolic BP 38% greater than HCTZ. Three trials comparing HCTZ with CTLD were included in this meta‐analysis at doses of 50 mg HCTZ vs 25 mg CLTD, 12.5 mg HCTZ v 6.25 mg CLTD and 25 mg HCTZ vs 12.5 mg CLTD, with an overall greater SBP reduction with CLTD of −3.6 mmHg (95% CI, −7.3 to 0, P = .052).20 This result is in line with the results of indirect comparisons in previous meta‐analyses.18, 21 Possibly due to its duration of action, CTLD has shown to be superior compared to HCTZ in reducing 24‐hour ambulatory BP. Ernst et al. 50 performed an 8‐week crossover study and showed that 24‐hour mean SBP was reduced by −12.4 ± 1.8 mmHg with CLTD (25 mg daily) and −7.4 ± 1.7 mmHg with HCTZ (50 mg daily; P = .054).

The efficacy of CTLD in reducing MACE has been confirmed in several RCTs. In the largest hypertension trial ever undertaken (ALLHAT), CTLD was more effective than ACE in reducing MACE and more effective than CCB in preventing congestive heart failure51 in black individuals, those with diabetes, the elderly and those with metabolic syndrome. In the SHEP trial52 CTLD at the dose of 12.5–25 mg daily reduced the incidence of stroke in patients aged >60 years.

The recommended dose in clinical practice (12.5–25 mg daily) has not been associated with major safety concerns regarding hypokalaemia. In the ALLHAT trial, CTLD caused a decrease in potassium levels of approximately 0.2–0.5 mmol/L.53 In the same trial, new onset of diabetes was greater in the diuretic‐based arm (11.6%) compared to the ACE (8.1%) and CCB (9.8%) arms; however, the outcome analysis did not show a negative impact in terms of increased risk of MACE. In comparison with HCTZ, hyponatraemia is more common with CTLD. However, the need for a lower dose of CTLD than HCTZ to achieve similar reduction of BP is likely to compensate for the increased risk of hyponatraemia.26

2. THIAZIDE DIURETICS IN THE UK

The available guidelines for the management of hypertension recommend first‐line drug treatment options according to patients' individual clinical need (Table 1 ). Studies worldwide have highlighted that, over the past 25 years, there has been a consistent increase in the use of ACE, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and CCBs and many clinical studies have showed no consistent differences in antihypertensive efficacy, side effects or quality of life within these drug classes.54

Since 2011, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has recommended the use of ACE/ARB or CCB as first‐line treatment in hypertension and data released in 2018 by the Prescribing and Medicine Team, NHS Digital confirmed that from 2007 to 2017 there was a 86.1 and 108.2% increase in the number of items of ramipril and amlodipine dispensed, respectively. However, over the same period there was a drop of 42.9% for BDTZ dispensed.

Thiazide diuretics are still among the most prescribed classes of antihypertensives worldwide, but over the past half century only a few studies have directly compared thiazide‐type and thiazide‐like diuretics in RCTs. Using data from a meta‐analysis,55 thiazide‐like diuretics appear more effective compared to thiazide‐type in reducing BP with no significant difference in electrolytes or metabolic disturbance between the 2 types of agent. Given the noninferiority compared to thiazide‐type, the clear outcome data (particularly for CLTD) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations, thiazide‐like would be expected to be the most commonly prescribed type of diuretics in the UK. However, this appears not to be the case according to the data released on the prescriptions in Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

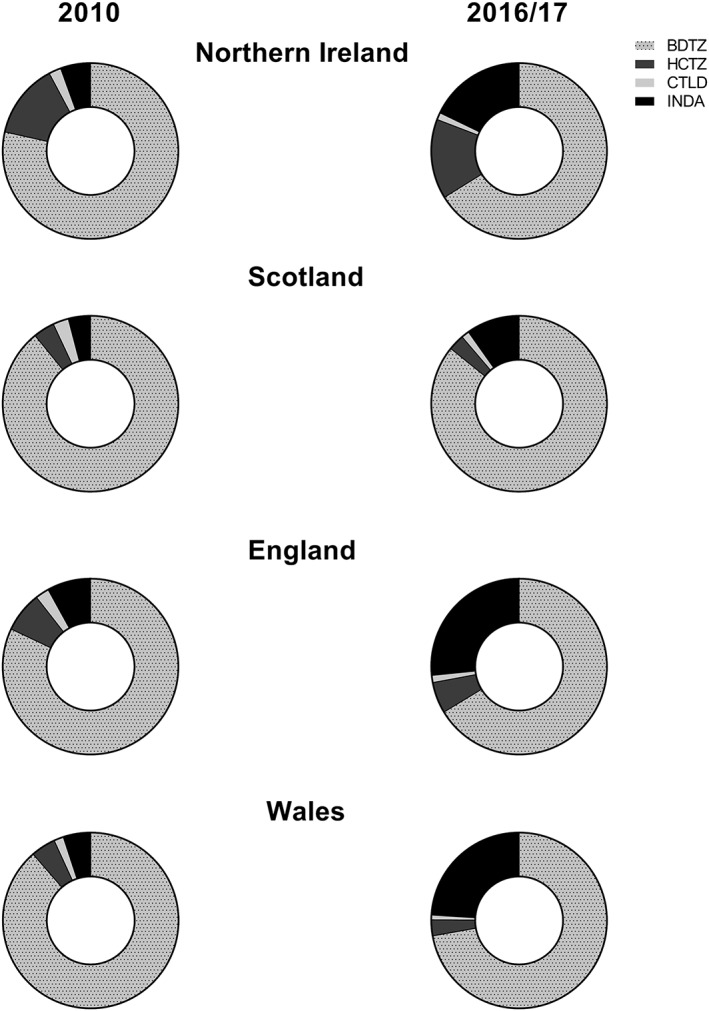

The most recently available prescription cost analysis data were gathered for Northern Ireland (2017) from the Business Services Organisation, for Scotland (2015/16) from the Information Services Division, for England (2017) from the Prescribing and Medicines Team NHS Digital and for Wales (2017) from NHS Wales Shared Services Partnership as well as data from 2010 for all 4 regions. Both generic and branded medicines containing BDTZ, HCTZ, CLTD and INDA were included provided they were licensed for hypertension as per the British National Formulary. The number of dispensed items and the dispensed quantity of each item was extracted for NI, Scotland, England and Wales. The total quantity of all dispensed items was calculated and each individual diuretic was expressed as % of the total (Figure 1). For each region of the UK, daily defined dose per 1000 inhabitants per day was calculated for BDTZ, HCTZ, CLTD and INDA (Table 2 ).

Figure 1.

Charts representing the relative use of indapamide (INDA), hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), bendroflumethiazide (BDTZ) and chlortalidone (CTLD) in the UK (divided by region) in the years 2010 and 2016/2017. Data are expressed as percentage

Table 2.

The defined daily dose/1000 inhabitants/day of indapamide (INDA), hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), bendroflumethiazide (BDTZ) and chlortalidone (CTLD) in each region of the UK

| Region of UK | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Ireland | Scotland | England | Wales | |||||

| 2010 | 2017 | 2010 | 2016 | 2010 | 2017 | 2010 | 2017 | |

| BDTZ | 37.19 | 23.63 | 51.22 | 35.40 | 38.23 | 20.02 | 44.47 | 25.38 |

| HCTZ | 4.22 | 3.29 | 2.10 | 1.02 | 2.70 | 1.26 | 2.13 | 0.68 |

| CTLD | 0.875 | 0.358 | 1.28 | 0.44 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.24 |

| INDA | 3.18 | 8.09 | 3.15 | 5.87 | 4.40 | 11.31 | 3.17 | 12.32 |

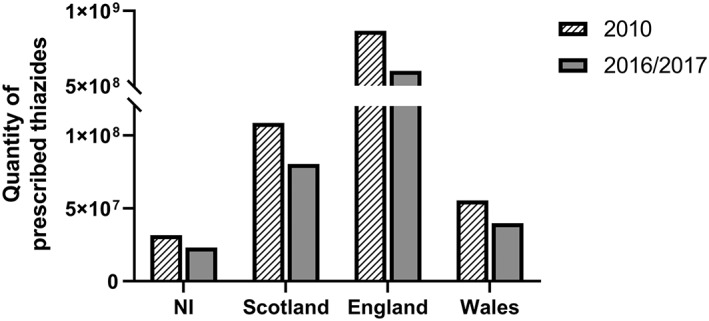

Overall, the prescriptions of thiazide diuretics have declined in all regions of the UK (Figure 2 , Table 2 ), a trend that may have been accelerated by a change of the guidelines in using ACE and or CCB as first‐line treatment. However, other factors may have played a role, in particular adherence to treatment. In fact, some studies have indicated that initial monotherapy treatment with thiazide diuretics is associated with poorer patient persistence, compared to ACE, ARB and β‐blockers.56, 57 Common reasons for treatment discontinuation include frequent urination or other side‐effects such as weakness, fatigue and electrolyte disturbances.58

Figure 2.

Bar chart representing the total prescribed quantity of indapamide, hydrochlorothiazide, bendroflumethiazide and chlortalidone in each region of the UK. Data from 2010 (all regions) and 2017 for Northern Ireland, England and Wales and 2016 for Scotland are listed

Despite some concerns regarding tolerability, a recent meta‐analysis found that the relative risk of treatment discontinuation due to adverse events with diuretics was no different than other classes of antihypertensive when compared to placebo.59 Similarly, in head‐to‐head comparisons there was no difference in the relative risk of treatment discontinuation due to adverse events with diuretics compared to all other classes of antihypertensive.59

To limit the ratio of side‐effects and improved tolerability patients are often prescribed a lower dose of diuretic when used in combination therapy with an agent from another antihypertensive class, and combination low‐dose therapy has been shown to increase BP‐lowering efficacy and reduce adverse side effects associated with higher‐dose monotherapy regimens. In this context, it is also important to balance the potential concern regarding tolerability with the clear outcome data for thiazide‐like diuretics particularly in some ethnic minority groups,51 a topic under current investigation in an ongoing UK‐based trial.60

Along with the overall reduction in prescriptions, the use of thiazide‐type overrides thiazide‐like and BDTZ is the most commonly prescribed diuretic in the UK. Prescriptions containing INDA has significantly increased since 2010 while CTLD represented a small fraction of the total both in 2010 and 2016/2017 with no increasing trend. This trend was similar in all UK regions with small geographical differences.

Of the many factors affecting trends in prescriptions, clinical inertia, availability of the products, price and the lack of fixed dose combinations may be important factors. Data derived from a series of annual surveys (from 1994 to 2011) in England show that, despite an improvement in awareness and treatment of hypertension over the years, only 37% of patients are well controlled.61 This number is projected to increase in the following decades, thus, more patients would require a medication review in which thiazide‐like diuretics may play a part.

The availability of CTLD across the UK is probably a major reason for its low prescription rate despite the evidence of its efficacy derived from RCTs. In fact, CTLD is available in the UK only at the dose of 50 mg, which is not recommended by the guidelines and in order to provide patients with 25 mg or 12.5 mg daily the tablet needs to be halved or quartered.

Finally, the lack of fixed‐dose combinations may represent a barrier for clinicians in switching patients from a conventional thiazide‐type diuretic (such as HCTZ) to a thiazide‐like diuretic. In the British National Formulary, CTLD is available in fixed‐dose combinations with non–first‐line agents (such as triamterene and atenolol) while INDA is only available with perindopril. The only fixed‐dose triple combination available in the UK contains HCTZ, which is also the only diuretic in fixed‐dose combination with ARB. Providing more options for combination therapies based on thiazide‐like diuretics (which are already available in other European countries) would help clinicians to increase the use of thiazide‐like diuretics, when tablet burden is thought to be important. In fact, fixed‐dose combinations help to improve persistence to treatment compared to free equivalent combination.62

In conclusion, thiazide‐like diuretics at the dose commonly employed in clinical practice are superior (or at least noninferior) to thiazide‐type diuretics in terms of BP reduction and prevention of MACE. However, despite recommendations of the current guidelines in the UK, thiazide‐type diuretics (in particularly BDTZ) are still the most commonly prescribed drugs, while the use of CLTD is still limited.

2.1. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY.63

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

Supporting information

Table S1

Pharmacokinetic profile of thiazide and thiazide‐like diuretics.

Table S2 Quantity of prescribed diuretics in each region of the UK. Data from 2010 (all regions) and 2017 for NI, England and Wales and 2016 for Scotland are listed.

McNally RJ, Morselli F, Farukh B, Chowienczyk PJ, Faconti L. A review of the prescribing trend of thiazide‐type and thiazide‐like diuretics in hypertension: A UK perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2707–2713. 10.1111/bcp.14109

There is no principal investigator for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56‐e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou B, Bentham J, Di Cesare M, et al. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population‐based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):37‐55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Public Health England . Hypertension prevalence estimates in England for local populations. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hypertension-prevalence-estimates-for-local-populations. 2016.

- 4. Moody A, Mindell J, Faulding S. Health Survey for England 2016 Prescribed medicines. NHS Digital. http://healthsurvey.hscic.gov.uk/media/63790/HSE2016-pres-med.pdf. December 2016. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- 5. Wang YR, Alexander GC, Stafford RS. Outpatient hypertension treatment, treatment intensification, and control in Western Europe and the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):141‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure‐lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 5. Head‐to‐head comparisons of various classes of antihypertensive drugs‐overview and meta‐analyses. J Hypertens. 2015;33(7):1321‐1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Obermüller N, Bernstein P, Velázquez H, et al. Expression of the thiazide‐sensitive Na‐cl cotransporter in rat and human kidney. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(6 Pt 2):F900‐F910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bataillard A, Schiavi P, Sassard J. Pharmacological properties of indapamide. Rationale for use in hypertension. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37(Suppl. 1):7‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruce Campbell D, Brackman F. Cardiovascular protective properties of Indapamide. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(17):11H‐27H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carlsen JE, Køber L, Torp‐Pedersen C, Johansen P. Relation between dose of bendrofluazide, antihypertensive effect, and adverse biochemical effects. BMJ. 1990;300(6730):975‐978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021‐3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in adults. J am Coll Cardiol. 2017;2017:23976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(5):506‐525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management: Clinical Guideline 127, 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- 15. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/. 2019. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- 16. Messerli FH, Makani H, Benjo A, Romero J, Alviar C, Bangalore S. Antihypertensive efficacy of hydrochlorothiazide as evaluated by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. J am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(5):590‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Julius S. Risk/benefit assessment of beta‐blockers and diuretics precludes their use for first‐line therapy in hypertension. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2706‐2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ernst ME, Carter BL, Zheng S, Grimm RH. Meta‐analysis of dose‐response characteristics of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone: effects on systolic blood pressure and potassium. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(4):440‐446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carter BL, Ernst ME, Cohen JD. Hydrochlorothiazide versus Chlorthalidone: evidence supporting their interchangeability. Hypertension. 2004;43(1):4‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB, Tandon S, Sica DA. Head‐to‐head comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide with indapamide and chlorthalidone: antihypertensive and metabolic effects. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1041‐1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peterzan MA, Hardy R, Chaturvedi N, Hughes AD. Meta‐analysis of dose‐response relationships for hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and bendroflumethiazide on blood pressure, serum potassium, and urate. Hypertension. 2012;59(6):1104‐1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pool PE, Applegate WB, Woehler T, Sandall P, Cady WJ. A randomized, controlled trial comparing diltiazem, hydrochlorothiazide, and their combination in the therapy of essential hypertension. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13(5):487‐493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leren P, Helgeland A. Coronary heart disease and treatment of hypertension. Some Oslo study data. Am J Med. 1986;80(2 Suppl. 1):3‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wing LMH, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin‐converting–enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;34(7):583‐592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vinereanu D, Dulgheru R, Magda S, et al. The effect of indapamide versus hydrochlorothiazide on ventricular and arterial function in patients with hypertension and diabetes: results of a randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2014;168(4):446‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Blijderveen JC, Straus SM, Rodenburg EM, et al. Risk of hyponatremia with diuretics: Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide. Am J Med. 2014;127(8):763‐771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilson L, Nair KV, Saseen JJ. Comparison of new‐onset gout in adults prescribed Chlorthalidone vs hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2014;16(12):864‐868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooper‐DeHoff RM. Thiazide‐induced dysglycemia: it's time to take notice. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6(10):1291‐1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weir MR, Flack JM, Applegate WB. Tolerability, safety, and quality of life and hypertensive therapy: the case for low‐dose diuretics. Am J Med. 1996;101(3A):83S‐92S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown MJ, Williams B, Morant SV, et al. Effect of amiloride, or amiloride plus hydrochlorothiazide, versus hydrochlorothiazide on glucose tolerance and blood pressure (PATHWAY‐3): a parallel‐group, double‐blind randomised phase 4 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(2):136‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) . Some Drugs and Herbal Products. IARC Monographs On The Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. https://publications.iarc.fr/132. Vol 108. Accessed April 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pottegård A, Hallas J, Olesen M, et al. Hydrochlorothiazide use is strongly associated with risk of lip cancer. J Intern Med. 2017;282(4):322‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pedersen SA, Gaist D, Schmidt SAJ, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Pottegård A. Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a nationwide case‐control study from Denmark. J am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):673‐681.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pottegård A, Pedersen SA, Johannesdottir Schmidt SA, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Gaist D. Association of hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of malignant melanoma. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1120‐1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pedersen SA, Johannesdottir Schmidt SA, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Pottegård A, Gaist D. Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk for Merkel cell carcinoma and malignant adnexal skin tumors: a nationwide case‐control study. J am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):460‐465.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Faconti L, Ferro A, Webb AJ, Cruickshank JK, Chowienczyk PJ. Hydrochlorothiazide and the risk of skin cancer. A scientific statement of the British and Irish hypertension society. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33(4):257‐258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kreutz R, Algharably EAH, Douros A. Reviewing the effects of thiazide and thiazide‐like diuretics as photosensitizing drugs on the risk of skin cancer. J Hypertens. 2019;37:000‐000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Musini VM, Nazer M, Bassett K, Wright JM. Blood pressure‐lowering efficacy of monotherapy with thiazide diuretics for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:CD003824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiggam MI, Bell PM, Sheridan B, Walmsley A, Atkinson AB. Low dose Bendrofluazide (1.25 mg) effectively lowers blood pressure over 24 h: results of a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled crossover study. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12(5):528‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. xIsles CG, Kitchin NR. A randomised double‐blind study comparing nifedipine GITS 20 mg and bendrofluazide 2.5 mg administered once daily in mild‐to‐moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13(1):69‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Macfarlane TV, Pigazzani F, Flynn RWV, Macdonald TM. The effect of indapamide versus bendroflumethiazide for primary hypertension: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(2):285‐303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sassard J, Bataillard A, McIntyre H. An overview of the pharmacology and clinical efficacy of indapamide sustained release. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2005;19(6):637‐645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Senior R, Imbs JL, Bory M, et al. Indapamide reduces hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy: an international multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22:S106‐S110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gosse P, Sheridan DJ, Zannad F, et al. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients treated with indapamide SR 1.5 mg versus enalapril 20 mg: the LIVE study. J Hypertens. 2000;18(10):1465‐1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marre M, Puig JG, Kokot F, et al. Equivalence of indapamide SR and enalapril on microalbuminuria reduction in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes: the NESTOR* study. J Hypertens. 2004;22(8):1613‐1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. PATS Collaborating Group . Post‐stroke antihypertensive treatment study. A preliminary result. Chin Med J (Engl). 1995;108(9):710‐717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patel J, Chalmers N, Chapman L, et al. Randomized trial of a perindopril‐based blood pressure‐lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or ischemic attack. Lancet. 2001;358(9287):1033‐1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chalmers J, Arima H, Woodward M, et al. Effects of combination of perindopril, indapamide, and calcium channel blockers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from the action in diabetes and vascular disease: Preterax and diamicron controlled evaluation (ADVANCE) trial. Hypertension. 2014;63(2):259‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887‐1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ernst ME, Carter BL, Goerdt CJ, et al. Comparative antihypertensive effects of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone on ambulatory and office blood pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):352‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wright J, Reynolds D, Willis G, Edwards M. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to or Calcium Channel blocker vs diuretic. JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981‐2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. SHEP Cooperative Research Group . Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265(24):3255‐3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Alderman MH, Piller LB, Ford CE, et al. Clinical significance of incident hypokalemia and hyperkalemia in treated hypertensive patients in the antihypertensive and lipid‐lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial. Hypertension. 2012;59(5):926‐933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Caceres MC, Moyano P, Fariñas H, et al. Trends in antihypertensive drug use in Spanish primary health care (1990‐2012). Adv Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;04(01):1‐4. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liang W, Ma H, Cao L, Yan W, Yang J. Comparison of thiazide‐like diuretics versus thiazide‐type diuretics: a meta‐analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(11):2634‐2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Conlin PR, Gerth WC, Fox J, Roehm JB, Boccuzzi SJ. Four‐year persistence patterns among patients initiating therapy with the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan versus other antihypertensive drug classes. Clin Ther. 2001;23(12):1999‐2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elliott WJ, Plauschinat CA, Skrepnek GH, Gause D. Persistence, adherence, and risk of discontinuation associated with commonly prescribed antihypertensive drug monotherapies. J am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(1):72‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, John RE. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003;326(7404):1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood‐pressure‐lowering treatment in hypertension: 9. Discontinuations for adverse events attributed to different classes of antihypertensive drugs: meta‐analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2016;34(10):1921‐1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mukhtar O, Cheriyan J, Cockcroft JR, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial evaluating differential responses to antihypertensive drugs (used as mono‐ or dual therapy) on the basis of ethnicity: the comparIsoN oF optimal hypertension RegiMens; part of the ancestry informative markers in HYp. Am Heart J. 2018;204:102‐108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Falaschetti E, Mindell J, Knott C, Poulter N. Hypertension management in England: a serial cross‐sectional study from 1994 to 2011. Lancet. 2014;383(9932):1912‐1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Du LP, Cheng ZW, Zhang YX, Li Y, Mei D. The impact of fixed‐dose combination versus free‐equivalent combination therapies on adherence for hypertension: a meta‐analysis. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(5):902‐907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1091‐D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Pharmacokinetic profile of thiazide and thiazide‐like diuretics.

Table S2 Quantity of prescribed diuretics in each region of the UK. Data from 2010 (all regions) and 2017 for NI, England and Wales and 2016 for Scotland are listed.