Abstract

Aims

Pharmacists have been contributing to the care of residents in nursing homes and play a significant role in ensuring quality use of medicine. However, the changing role of pharmacist in nursing homes and their impact on residents is relatively unknown.

Methods

Six electronic databases were searched from inception until November 2018 for articles published in English examining the services offered by pharmacists in nursing homes. Studies were included if it examined the impact of interventions by pharmacists to improve the quality use of medicine in nursing homes.

Results

Fifty‐two studies (30 376 residents) were included in the current review. Thirteen studies were randomised controlled studies, while the remainder were either pre–post, retrospective or case–control studies where pharmacists provided services such as clinical medication review in collaboration with other healthcare professionals as well as staff education. Pooled analysis found that pharmacist‐led services reduced the mean number of falls (−0.50; 95% confidence interval: −0.79 to −0.21) among residents in nursing homes. Mixed results were noted on the impact of pharmacists' services on mortality, hospitalisation and admission rates among residents. The potential financial savings of such services have not been formally evaluated by any studies thus far. The strength of evidence was moderate for the outcomes of mortality and number of fallers.

Conclusion

Pharmacists contribute substantially to patient care in nursing homes, ensuring quality use of medication, resulting in reduced fall rates. Further studies with rigorous design are needed to measure the impact of pharmacist services on the economic benefits and other patient health outcomes.

Keywords: inappropriate medication, medication review, nursing home, pharmacist, polypharmacy, systematic review

What is already known about this subject

The role of pharmacists has evolved over the past few decades from being product‐centred to patient‐centred.

Some core services offered by pharmacists include medication review and management, health promotion, vaccination as well as counselling services.

Services provided by pharmacists can have a positive impact on patient health, quality of life as well as cost‐savings.

The services offered by pharmacists to nursing home residents and its healthcare providers, and the impact of these services are relatively unknown.

What this study adds

Pharmacists are expected to be more clinically experienced and provide quality healthcare to patients.

Pharmacists led medication review services in nursing homes can reduce the risk of falls among nursing home residents.

Evidence is less clear on the impact to reduce mortality or hospitalisation and admission, as well as the economic impact.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the next 2 decades, the population aged >60 years will double, with most of them living in low‐ and middle‐income countries.1 Studies have shown that due to the presence of multiple morbidities, older adults tend to be prescribed with more medications, which leads to polypharmacy.2, 3 This is a growing concern especially among those who reside in nursing homes, as the residents are generally frailer and thus imposes greater health risks and complications, such as an increase in adverse drug events, disability, hospitalisation and death.4, 5 Extensive research has shown the relationship between polypharmacy and negative clinical consequences,6, 7 including cognitive impairments, falls, fractures, drug interactions as well as adverse drug events (ADEs). These risks are higher among the frail and very old adults (≥80 years), due to physiological changes with age. As such, the management of medication use among the older adults in nursing homes is crucial to prevent unnecessary harm and to improve the quality use of medicines.

Pharmacists play a significant role in facilitating evidence‐based information and to educate the public on the appropriate use of medicines especially in nursing homes.8 For example, quality use of medicines is a central objectives of Australia's National Medicines Policy. The goal is to achieve best possible use of medicines, through various interventions such as pharmacist‐led medication reviews to improve health outcomes. Indeed, pharmacist‐led medication reviews are widely described in the literature and inform some intervention studies conducted in many countries including Sweden, UK, Switzerland, USA and Australia. Several systematic reviews that show a positive impact of pharmacist interventions have also been published but these studies have mostly focused on the impact of the interventions in the community9 or tertiary care settings.10, 11, 12 Studies in the aged care sector are limited.

Few systematic reviews have examined the impact of interventions by pharmacists in nursing homes. In a review by Verrue and colleagues in 2009,13 the authors only searched for randomised controlled studies (RCTs) aimed at improving the quality of prescribing in nursing homes by pharmacists. The authors found 8 studies and mixed evidence on the efficacy of interventions by pharmacists in reducing inappropriate prescribing. Another study by Thiruchelvam et al. had a limited search to studies from 1998 onwards and thus did not provide a true picture of the various pharmacist services offered in nursing homes and how these services have evolved over the past few decades.14 The most recent Cochrane review examined interventions that aim to optimise prescribing among older adults in care homes, but these did not specifically focus on pharmacists only.15 As such, the aim of our current systematic review was to provide an overview of the evidence of pharmacist‐led interventions to improve the quality use of medicine in nursing homes and determine the impact of these interventions in nursing homes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy

We searched for articles describing interventions by pharmacist to improve the quality use of medicine in nursing homes. Electronic searches were performed on PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, AMED and CENTRAL from database inception to November 2018. Search terms used include pharmacy, pharmacist, pharmacy services, pharmaceutical service, pharmaceutical care, quality use of medicine, aged care, residential care and nursing home. This was supplemented with hand searches of reference lists of retrieved articles and conference abstracts.

2.2. Study selection

Retrieved articles were independently screened by title and abstracts by 2 reviewers (Y.W.T. and S.W.H.L.). Studies were included if: (i) they involved a service provided by a pharmacist and (ii) the intervention was in a residential, aged‐care or nursing home. Any study design (e.g. cross‐sectional, randomised controlled, pre–post) were eligible for inclusion. However, studies that involved interventions by other healthcare professionals (e.g. physician, nurses, dietitians), and review articles and comments were excluded.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted using a standardised data collection template. Extracted data included: study characteristics (author, year, study location), participant demographics, services provided and outcome measurements. Services that were provided by pharmacist in nursing homes were classified based upon an adaptation of definition previously proposed by Hatah and colleagues16 (see Table 1). We included a range of outcomes including patient reported outcomes such as mortality rates, fall rates, number of fallers, quality of life, economic outcome such as cost savings and healthcare service utilisation such as acceptance rates of recommendations as these were important indicators for patient safety. We subsequently assessed data quality of pre–post studies, retrospective and case–control studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale,17 and graded studies based upon the 3 criteria of selection, comparability and outcome. For RCTs, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, which assessed the study based upon the following criteria: random sequence generation, blinding of outcome assessment, blinding of participant and personnel, allocation concealment, selective reporting, incomplete outcome and other bias. We subsequently used the GRADE criteria to assess the quality of evidence for each outcome reported of RCTs, or observational studies if RCTs were not available. These were based on the domains risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias.18 All disagreements between investigators were resolved through a consensus.

Table 1.

Objective description of the services provided by pharmacist

| Name of service | Possible intervention provided |

|---|---|

| Clinical medication review | An intervention to address issues related to a patient's use of medication in the context of their clinical condition such as medication appropriateness, effectiveness, cost‐effectiveness, deprescribing, and monitoring to meet the patient's needs. The pharmacist may also consider drug interactions, adherence to medication, lifestyle, nonmedication interventions and unmet needs. |

| Staff education | Training and support given to healthcare professional staff at nursing home/aged care facility. Intervention could involve either face‐to‐face education with relevant healthcare professionals such as prescriber or nurses to discuss relevant clinical practice. |

| Multidisciplinary team meeting | A meeting between healthcare professionals from 1 or more clinical disciplines who together make decisions regarding recommended treatment of a resident and ensure that the needs are met. The meeting can occur either face‐to‐face, by phone or video conference, or a combination of both. |

2.4. Statistical analyses

We evaluated the impact of pharmacists' intervention on outcomes such as fall rates, number of falls, mortality, hospital usage and admission, quality of prescribing, and number of adverse events. We pooled the results if comparable outcome data from 2 or more studies were available. In the meta‐analyses, we used the random effects meta‐analysis model, as we assumed that clinical and methodological heterogeneity was likely to exist and have an effect on the results. Results are presented as risk ratio and their respective 95% confidence intervals or mean differences and their 95% confidence intervals for continuous outcomes. Funnel plots were created when 10 or more studies were available to assess the likelihood of publication bias. Since none of the meta‐analyses included 10 or more studies, a thorough assessment of publication bias was not feasible. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistics. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

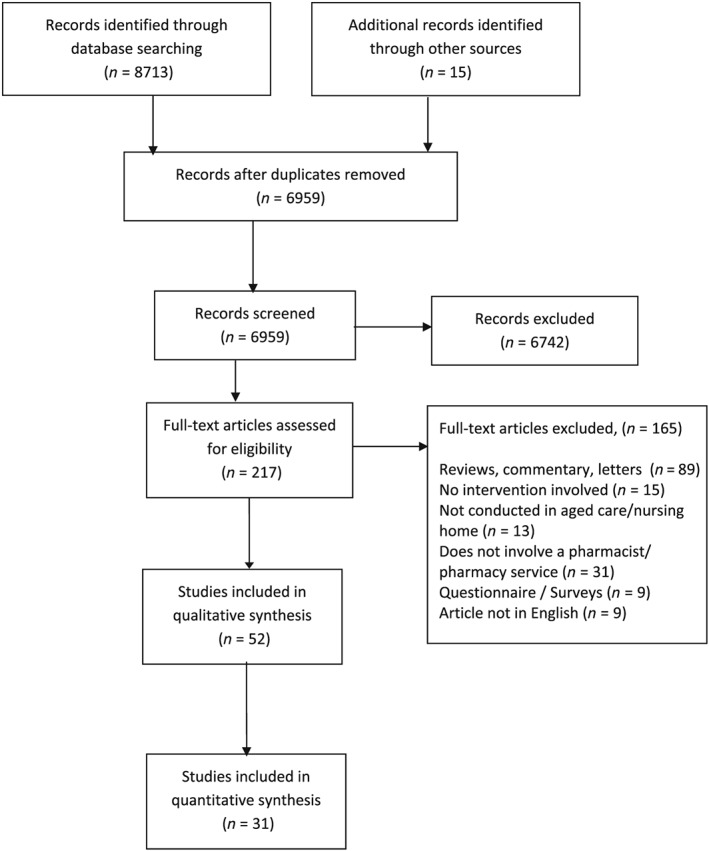

Our search identified 6959 unique articles and 217 articles were eligible for full text assessment. Fifty‐two articles describing 50 unique studies were included in the current review (Figure 1). The included articles were from North America (n = 25), Europe (n = 17) and Australia (n = 10). Twelve of the studies were conducted between 1978 and 1990, 9 between 1991 and 2000, 19 between 2001 and 2010 and 12 between 2011 and 2017. Thirteen studies were RCTs, 28 were pre–post studies, 6 were retrospective studies and 5 were case–control studies.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow of articles

A total of 30 376 nursing home residents were included in the review, and the median age of residents was 81 years (range 65–88 years). Information pertaining to the residents' baseline characteristics (e.g. proportion of dementia residents, number of medications taken) were poorly reported. In 29 studies for which data were available, the residents reported to be receiving 7.9 medications at baseline.

3.2. Quality of included studies

3.2.1. Case–control, pre–post and retrospective studies

Most of the included case–control and pre–post or retrospective studies were of average quality, with a lower mean score of 4.2 for pre–post or retrospective studies compared to 6.2 for case–control studies (Tables S2 and S3). This was mainly due to the small sample sizes, and poor reporting quality of included studies. This was expected as most studies were conducted in a single nursing home, thus had small sample sizes. Most of the studies did not report outcomes of interest such as mortality or fall rates. Similarly, most studies had not adjusted for potentially important case‐mix differences in their analyses. However, all studies used medical records to verify their outcomes.

3.2.2. RCTs

Most of the RCTs had a low risk of bias in the selection of reported results. Similarly, they had a low risk of bias for random sequence generation (9 studies; 69.2%), blinding of outcome assessment (9 studies; 69.2%) and incomplete outcome data domain (8 studies; 61.5%). Nevertheless, most studies had some risk of bias due to poor allocation concealment (9 studies; 69.2%) as well as blinding of participant and personnel domain (9 studies; 69.2%). This was probably due to the nature of intervention, in which it was very difficult to blind both the patient and the pharmacist who was conducting the intervention (Figure S1).

3.3. Pharmacists' services to nursing homes

3.3.1. Clinical medication review

Clinical medication reviews were the central activity performed in nursing homes, which was reported in 30 studies (Table 2). These reviews involved medication reconciliation, which either targeted specific medications (e.g. digoxin) or medication classes (e.g. laxatives, antipsychotics, antibiotics), or addressed specific medication interactions in an attempt to optimise medication use or addressed issues on polypharmacy. The criteria used to determine the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy used were varied: 5 studies used the Beers criteria,36, 41, 49, 50, 51 4 studies used the medication appropriateness index (MAI),41, 52, 53, 54 2 studies used the START/STOPP criteria41, 42 while many studies measured the reduction in adverse events, such as hospitalisation days or falls. These interventions were reported to be effective in detecting and resolving medication related problems,27, 55 especially those related to psychoactive drugs,56 and improved prescribing practice (as assessed using medication appropriateness index), and resulted in significant cost savings.29, 57, 58

Table 2.

Summary of studies that involved clinical medication review

| Author, y (country) | Study design and setting | No of pharmacists involved in the intervention | No of residents and settings | Service provided, duration and frequency | Study period | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper,19 1978 (USA) | Pre–post study, skilled nursing facility | Not reported | 142 residents in 1 nursing facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review examining patient's active problems moly, status of therapeutic endpoint, need of and usage of each regularly scheduled or as needed drug | 12 mo | Reduction in number of regularly scheduled drugs per patient by 19.4%, when necessary drugs by 45.9% and total drugs per patient by 33.8% (from 7.22 to 4.78). |

| Miller,20 1980 (USA) | Pre–post study, skilled nursing facility | 3 | 79 residents from 2 skilled nursing facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 6 mo | Identification of issues related to disease management, with recommendations made. A total of 33 (71.7%) were accepted by physicians. |

| Strandberg,21 1980 (USA) | Retrospective analysis, long‐term care facilities | Not reported | 404 residents from a skilled nursing facility and intermediate care facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 7 y | Over an 8‐y period, there was reduction in number of prescription drugs (42.8%), nonprescription drugs (34.4%) and number of prescription doses (34.6%) consumed by residents, which led to cost savings. |

| Young,22 1981 (USA) | Pre–post study, skilled nursing facility | 2 | 25 residents from a facility | Introduction of a pharmacist‐led medication review | 1 mo | A reduction of total number of drugs and doses was noted, which can be translated to savings of $0.40/patient/d or $1.7 million annually. |

| Garnett,23 1981 (USA) | Pre–post study, extended care facility | 1 | 24 residents from an extended care facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 2 mo | Issues pertaining to disease management, dispensing and drugs were the most commonly identified. The high acceptance and implementation rate suggest potential role of a clinical pharmacist to the quality of resident care. |

| Chrymko24 1982, (USA) | Pre–post study, teaching hospital | 1 | 19 of 21 patients from a long‐term care unit of a hospital | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 2 mo | There was a reduction in average number of scheduled medications among residents in nursing home, but this returned to baseline levels at 14 mo follow‐up. |

| Studnicki‐Gizbert,25 1983 (Canada) | Case–control, nursing home | Not reported | 120 residents from 3 homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | Pharmacist medication review led to a modest improvement in the drug usage among nursing home residents, with a total net saving of $720 with employment of a pharmacist. |

| Thompson,26 1984 (USA) | Case–control, nursing home | 2 | 152 residents from 1 nursing home | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 12 mo | There were fewer death in the intervention group, and lower average number of drugs per patients. There is a potential cost savings of $70,000/y per 100 skill nursing facility beds to the healthcare. |

| Pink,27 1985 (USA) | Retrospective study, long‐term care facility | Not reported | 83 residents from a long‐term care facility | Introduction of a clinical pharmacist to conducted mediation review | 24 mo |

Introduction of a consultant pharmacist improved digoxin related therapy and monitoring. |

| Miller,28 1991 (Unites States) | Pre–post study, intermediate care facility | 1 | 58 residents from a skilled nursing facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review with moly unit inspection as well as serving as a drug information resource | Not reported | The pharmacist positively impacted rational drug use, by reducing the average number of drugs taken per patient as well as patient monitoring |

| Laucka,29 1992 (USA) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 1 | All residents from a nursing home | Pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | A reduction in number of when necessary and scheduled medicine was noted, resulting in a cost saving of approximately $27 400. |

| Rees,30 1995 (United Kingdom) | Case–control, nursing home | 1 | 160 residents in 9 residential home | Pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | There was a poor acceptance rate of the recommendations by physicians suggesting a need for collaboration between general practitioner and pharmacist. |

| Bellingan,31 1996 (South Africa) | Pre–post study, elderly care facility | 1 | 85 residents in an elderly care facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | Intervention reduced the overall incidence of all drug‐related problems and polypharmacy. |

| Deshmukh,32 1996 (United Kingdom) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 1 | 79 residents in 2 nursing homes | Pharmaceutical advisory service to review and amend policy related to medication storage and administration and pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | A reduction in number of when necessary drugs, bed sores and residents who reported adverse events was noted. This was coupled with an improvement in the administrative recordings, with a net potential cost saving of $212 000. |

| Elliott,33 1999 (Australia) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 2 | 128 residents in 4 nursing homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | Changes recommended led to an improvement in patient wellbeing and reduced risk of adverse drug events. The review was reported to be useful and benefited residents, with an estimated yearly reduction in medication costs of $59.76 per resident reviewed. |

| Furniss,34 2000 (United Kingdom) | Randomised controlled study, nursing home | 1 | 330 residents from 14 homes (158 in intervention and 172 in control) | Pharmacist‐led medication review with recommendations and follow up | 8 mo | The number of inappropriate drugs prescribed reduced, with a corresponding saving in drug costs. |

| Ulfvarson,35 2003 (Sweden) | Randomised controlled study, nursing home | 1 | 80 residents in 9 nursing homes (43 in intervention and 37 in control) | Pharmacist‐led medication review specialising in clinical pharmacology and cardiology | 3 mo | Drug reviews are of value to reduce the negative effects but limiting to only cardiovascular drugs makes it non cost‐effective. As such, the reviews should involve >1 class of drug. |

| Trygstad,36 2005 (USA) | Pre–post study, long‐term care | 110 | 253 nursing home | Pharmacist‐led medication review targeting individuals with >18 prescription fills within 90 d | 13 mo | Supplemental programme of medication reviews that targeted by high drug utilisation resulted in a reduction in the persistence of potential drug therapy alerts and was cost beneficial. It also resulted in an improvement of health outcomes. |

| Zermansky,37 2006 (United Kingdom) | Randomised controlled study, care homes | 1 | 661 residents in 65 nursing homes (331 in intervention and 330 in control) | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 6 mo | Clinical medication review by a pharmacist identified medicine related problems in approximately 80% of care home residents, requiring intervention in 1 of their prescribed medications. |

| Bruce,38 2007 (United Kingdom) | Pre–post study, care homes | Not reported | 1340 residents in 40 nursing homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review | Not reported | Medication change involving stopping, withdrawing ineffective or no longer appropriate drugs results in a savings of £100 per patient. |

| Nishtala,39 2009 (Australia) | Retrospective analysis, aged care home | 10 | 500 de‐identified RMMR reports from 62 aged‐care homes | Residential medication management reviews performed by accredited clinical pharmacists | ‐ | Residential medication management review reduced prescribing of sedative and anticholinergic drugs in older people, resulting in a significant decrease in the drug burden index score. The most common drugs implicated were related to alimentary, cardiovascular, central nervous system and respiratory system. |

| Gugkaeva,40 2012 (USA) | Pre–post study, long‐term care facility | Not mentioned | 53 residents in a long‐term care facility | Pharmacists led antibiotic stewardship | 3 mo | The inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics is a major problem in nursing homes, and stewardship led to a 50% reduction in inappropriate use. Additional further research is needed to determine if pharmacists can serve as an effective tool for improving antibiotic use in such settings. |

| Verrue,41 2012 (Belgium) | Randomised controlled study, nursing home | 1 | 384 residents in 2 nursing homes (1 home: 230 in intervention; 1 home: 154 in control) | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 6 mo | The study noted that pharmacist‐conducted medication review only modestly improved the appropriateness of prescribing and a significant reduction of the number of Beers drugs. This could be attributed to the low implementation rate of the pharmacist recommendations. |

| Frankenthal,42 2014 (Israel) | Randomised study, chronic care geriatric facility | 1 | 359 residents in 1 chronic care geriatric facility (183 in intervention and 176 in control) | Pharmacist‐led medication review using STOPP/START criteria to identify for inappropriate medications | 12 mo | Implementation of medication review using STOPP/START criteria reduced the number of medications, falls and cost by US$29/participant/mo. |

| Gheewala,43 2014 (Australia) | Retrospective analysis, aged care facility | Not mentioned | 911 residents from aged care facilities | Residential medication management reviews of renally cleared medications performed by accredited clinical pharmacists | 17 mo | Residential medication management reviews significantly reduced drug‐related problems encountered among residents especially among chronic kidney disease individuals. Additional emphasis is needed in this group to monitor for decline in kidney function. |

| McLarin,44 2015 (Australia) | Retrospective analysis | Not mentioned | 814 residents' RMMR report | RMMRs performed by accredited clinical pharmacists | Not reported | Residential medication management reviews were effective in improving the use of anticholinergics and reducing the anticholinergic burden. |

| Chia,45 2015 (Singapore) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 2–3 for each nursing homes during the pre‐setup period, 1 for each nursing home during post‐setup period | 480 residents from 3 nursing homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review | 6 mo | The introduction of clinical pharmacists into nursing home improved the quality of care among residents and was cost saving (SGD 76.69/mo) |

| Nishtala,46 2016 (Australia) | Retrospective study | Not mentioned | 146 residents' RMMR report | RMMRs performed by accredited clinical pharmacists | ‐ | Application of the CHA2DS2‐VASc risk tool could assist medication review pharmacists in optimising antithrombotic therapy in older adults with atrial fibrillation. |

| Gemeli,47 2016 (USA) | Pre–post study, long‐term care facility | Not mentioned | 36 residents from 11 long‐term care facilities | Pharmacist‐led medication review and deprescribing of sedatives/hypnotics | Not reported | The introduction of a pharmacist to conduct chart reviews among long‐term care facilities resident could reduce the use of inappropriate sedative/hypnotic use among elderly population. |

| Lee,48 2017 (Canada) | Pre–post study, residential care | 3 | 28 residents from 1 residential care | Proton‐pump inhibitors drug use review and deprescribing | 8 weeks | There were limited benefits of deprescribing proton pump inhibitors, but tapering can be used to identify the lowest effective dose and may increase patient comfort with deprescribing in older populations. |

RMMR, residential medication management review

3.3.2. Multidisciplinary team meeting with clinical medication review

Seventeen studies involved multidisciplinary case conferencing between a physician, pharmacist and other allied healthcare professionals such as nurses. These were usually held 2–12 weeks after the clinical medication review to optimise the resident's pharmacotherapy plan (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of studies that involved multidisciplinary team meeting with clinical medication review or studies involving staff education only or staff education with clinical medication review

| Author, y (country) | Study design and setting | No of pharmacists involved in the intervention | No of residents and settings | Service provided, duration and frequency | Study period | Other healthcare professionals involved in study | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical medication review with multidisciplinary team meeting | |||||||

| Wilcher,59 1981 (USA) | Pre–post study, long‐term care facility | 1 | 143 residents from a long‐term care facility | Multidisciplinary team case conference where prevention of chronic pain among residents was discussed | 33 months | Physician, nurse | Pain management case conference with pharmacists improved the judicious use nonopioid pharmacotherapy such as paracetamol and other anti‐inflammatory agents. |

| Cooper,60 1985 (USA) | Pre–post study, long‐term care facility | 1 | 72 residents from a long‐term care facility | Pharmacist‐led medication review with case conference with physician | 48 months | Physician, nurse | Case conferencing reduced the number of drugs used by almost half, reduced admission rates as well as mortality rates. |

| Schmidt,61 1998 (Sweden) | Randomised controlled study, nursing home | Not mentioned, but usually 1 pharmacist per site | 1854 residents in 33 nursing homes (15 homes: 626 in intervention; 18 homes: 1228 in control group) | Multidisciplinary team‐care medication management | 12 months | Physician, nurse, licensed practical nurse and nurse aide | Intervention by multidisciplinary team effectively improved prescribing practice, increase staff knowledge and improve quality of care in nursing home. In particular, the prescribing pattern of antipsychotic drugs improved. |

| Eide,62 2001 (Norway) | Case–control study, nursing home | 1 pharmacist and 1 clinical pharmacologist | 467 residents in 5 nursing homes (388 in intervention and 79 in control group) | Pharmacist‐led medication review on hypnotic drug use followed by case conferencing | Not reported | Physician, nurse | The intervention significantly influenced the quality of use of hypnotics and there was marked reduction in prescribing of benzodiazepines. |

| King,63 2001 (Australia) | Case–control study, nursing home | 1 | 75 residents from 3 nursing homes. | Multidisciplinary team case conference for 30 minutes followed by development of case management plan | 8 months | General practitioner, nursing staffs, physiotherapist | A reduction in the number of medication orders and total cost of medications was noted, with an adjusted mortality data of 6% in the reviewed residents compared to 15% of those who were not reviewed. |

| Midlov,49 2002 (Sweden) | Randomised controlled study, nursing home | 5 | 157 residents from 48 nursing homes (92 in intervention and 66 in control) | Weekly multidisciplinary team medication review | 6 months | Physician, neurologist, neuropsychiatrist, clinical pharmacologist | Poor drug use and documentation of indications in geriatric nursing‐home patients, with 2 in every 5 drugs deemed inappropriate. However, no significant differences were noted in the SF‐36 ‐ 36 Item Short Form SurveyADL ‐ Activities of daily livingbehave‐AD ‐ Behavorial Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease for epilepsy patients. |

| Christensen,50 2004 (USA) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 110 | 9208 residents in 253 nursing homes. | Pharmacist‐led medication review targeted at residents receiving ≥18 prescription refill within 90 d in consultation with prescribing physicians | 6 months | Physician | Reduction of polypharmacy and a reduction of drug costs as well as maintenance or enhancement of the quality of pharmaceuticals was seen |

| Crotty,54 2004a (Australia) | Cluster randomised–controlled study, residential aged care | 1 | 154 residents from 10 high level aged care facilities (100 in intervention and 54 in control) | Multidisciplinary case conference with medication review | 3 months | General practitioner, geriatrician, residential care staff, representative from Alzheimer's association | Improvement in the medication appropriateness especially benzodiazepine use. This did not result in any deterioration of resident behaviour. |

| Crotty, 2004c (Australia) | Randomised single blind study, long‐term care facility | Not reported | 110 residents in 85 long‐term care facility (56 in intervention and 54 in control) | Pharmacist‐led coordination of care transition from hospital to long‐term care facility which included a medication review and case conferencing | 1.5 months | Physician | Use of a pharmacist as a care coordinator was a feasible and simple option to reduce inappropriate medication use and improved quality of prescribing. |

| Lapane,51 2006 (USA) | Pre–post study, nursing homes | Consultant pharmacists and dispensing pharmacists | 4272 residents in 12 nursing homes | Fleetwood model of care comprising of medication review, communication with prescriber and formalised pharmacotherapy plan | 12 months | Prescriber | Most common issues identified were missing information/clarification needed, drug–age precautions, excessive duration alert, suboptimal regimen and need for additional laboratory test. Extending the role of the dispensing and consultant pharmacists beyond federally mandated drug regimen reviews is feasible, although ability to bill and be reimbursed for such services may ensure consistent prospective intervention. |

| Finkers,64 2007 (Netherlands) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 3 | 105 residents | Pharmacist‐ and nursing home physician‐led medication review with case conferencing | 8 months | Physician | The majority of patients had at least 1 drug prescribed for which the indication was unknown. Intervention decreased the number of drugs per patient, but half of the drug‐related problems remained unsolved. |

| Stuijt,53 2008 (Netherlands) | Pre–post study, residential home | 14 | 30 residents from 1 residential nursing home | Pharmacist‐led medication review followed by case conferencing with multidisciplinary healthcare team | 12 months | General practitioner, a member of nursing home | Integration of a clinical pharmacists into the healthcare team improved prescribing appropriateness as well as quality of prescribing. |

| Halvorsen,65 2010 (Norway) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 3 | 142 residents in 3 nursing homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review using established Norwegian classification tool, identification of drug related problem followed by weekly multidisciplinary case conferencing | Not reported | Physician, nurse | The multidisciplinary team intervention was suitable to identify and resolve drug‐related problems in nursing home settings, suggesting further involvement of pharmacists in clinical teams to achieve and maintain high‐quality drug therapy. |

| Patterson,66 2010 (Northern Irelend) | Cluster randomised controlled study, nursing home | 9 | 334 residents in 22 nursing homes (11 homes, 173 intervention and 11 homes, 161 in control) | Fleetwood model of care comprising of medication review, communication with prescriber and formalised pharmacotherapy plan | 12 months | Nurse, resident, carer/relative, general practitioner and other primary care team as needed | Using an adapted US model of pharmaceutical care focusing on inappropriate psychoactive medication, there was marked reductions in inappropriate drug use, but no effect on falls. This model was found to be more cost‐effective than usual care. |

| Brulhart,67 2011 (Switzerland) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 2 | 10 nursing homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review followed by multidisciplinary case conferencing | 24 months | Physician, geriatrician, nurse | There was a need to improve the use of medicines in terms of timing of administration and dosage, choice of appropriate drugs and drug–drug interactions follow up. These drugs were mainly related to alimentary tract and metabolism, nervous system, and cardiovascular system. |

| Davidsson,68 2011 (Norway) | Pre–post study, nursing home | 1 | 93 residents in 1 nursing home | Systematic comprehensive medication review by multidisciplinary team | 15 months | Physician, nurse | Medication reviews conducted by multidisciplinary teams were effective to improve the quality of drug treatment, significantly reducing both number of drugs and number of drug related problems. |

| Baqir,69 2014 (England) | Pre–post study, nursing home | Not mentioned | 422 residents in 20 care homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review with case discussion among a multidisciplinary team | 12 months | General practitioner, nurse | The multidisciplinary medication review could safely reduce inappropriate medication in elderly care home residents and could potentially save up to £77 703 in the study. |

| Staff education with/without clinical medication review | |||||||

| Elzarian,70 1980 (USA) | Pre–post study, long‐term care hospital | Not reported | 87 residents from 1 long‐term care hospital | Educational intervention to nurses to educate on laxative utilisation and pharmacist‐led medication review | 9 months | Physician, nurse | Significant decrease in laxative prescribing and administration especially for the bulk forming, lubricant and saline drug‐class, with substantial costs savings. |

| Avorn,56 1992 (USA) | Randomised controlled study, nursing home | 1 | 823 residents from 12 nursing homes (431 in intervention group and 329 in control group) | Comprehensive educational outreach programme to physician on geriatric psychopharmacology | 2 months | Physician, nurse, nursing assistant | Educational outreach improved the use of psychoactive drugs as well as reduced the use of long‐term benzodiazepines and antihistamine hypnotics. However, some deterioration in cognitive function and anxiety was noted in the intervention group. |

| Roberts,71 2001 (Australia) | Cluster randomised controlled study, nursing home | Not mentioned | 3230 residents in 52 nursing homes (13 homes: 905 intervention; 39 homes: 2325 in 39 control) | Problem‐based educational programme (6–9 seminars totalling 11 hours) on basic geriatric pharmacology, long‐term care such as depression, delirium, dementia, incontinence, sleep disorder, pain, falls to nurses and pharmacist‐led medication review | 12 months | Nurses | Reduction in drug use with no change in morbidity indices or survival. The use of benzodiazepines, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, laxatives, histamine H2‐receptor antagonists and antacids was significantly reduced in the intervention group. |

| Lau,72 2003 (Hong Kong) | Pre–post study, old age homes | Outreach pharmacists (no mention of how many) | 85 homes | Pharmacist‐led medication review with educational talks to staff at old age home on medications use | 8 months | Staffs at old age home | There were issues in the drug management system of nursing homes. These can be classified as in issues related to storage drug administration system, documentation and drug knowledge among staffs. These issues could be easily resolved through the introduction of a pharmacist. |

| Crotty,73 2004b (Australia) | Cluster randomised controlled study, nursing homes and hostels | 1 | 715 residents in 20 facilities (381 in intervention and 334 in control) | Multifaceted intervention incorporating audit, feedback and education to physicians and nurses on falls prevention, use of aspirin in stroke, monitoring of hypertension, risk of psychotropic drugs and benefits of using warfarin in residents with atrial fibrillation | 7 months | Physician, nurse | Intervention did not significantly improve fall rates, psychotropic drug use or when necessary antipsychotics. |

3.3.3. Staff education with/without clinical medication review

Another intervention offered to nursing homes involved staff education to healthcare professionals on topics such as fall and stroke prevention or to improve prescribing practices, knowledge and delivery of care (Table 3). Five studies involved an interactive group education session to improve the healthcare providers' knowledge on geriatric pharmacology, disease management as well as common issues encountered in geriatric populations. Some also included an introduction into the new professional roles of the clinical pharmacists (Table S4).

3.4. Outcomes of pharmacists' interventions

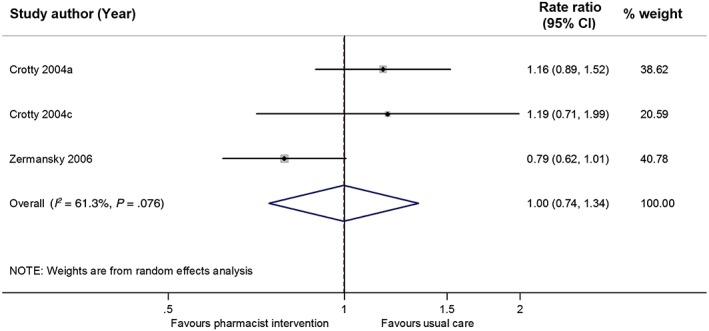

3.4.1. Number of fallers

Three studies reported the impact of their intervention on the number of fallers at the nursing home.37, 52, 54 Introduction of a pharmacist into nursing homes was found to have minimal impact on reducing the risk of falls among the residents (risk ratio: 1.00; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.74–1.34; I 2 = 61%, P = .99, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the odds of falling among residents following pharmacist intervention compared to usual care among residents. The size of the data markers is determined by weight from random‐effects analysis. CI, confidence interval

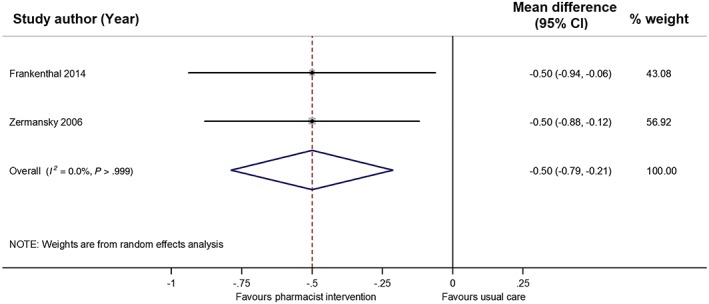

3.4.2. Fall rates

Three studies also reported the average fall rates after their intervention.37, 42, 66 Pharmacist‐led medication review was found to be effective in reducing the fall rates in 2 studies, while the study by Patterson reported otherwise. Only 2 studies provided the average number of fall and pooled estimates found that pharmacist intervention reduced the fall rates in nursing homes (Mean difference: –0.50; 95% CI: −0.79 to −0.21; I 2 = 0%, P = .001, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the mean number of falls among residents following pharmacist intervention compared to usual care. The size of the data markers is determined by weight from random‐effects analysis. CI, confidence interval

3.4.3. Mortality

Eight studies, which examined 1860 residents in total, reported mortality as an outcome.26, 34, 37, 42, 48, 52, 54, 60 In these studies, pharmacist intervention was reported to have led to a reduction in mortality rates. The pooled effect of pharmacists' intervention on mortality was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.63–1.27; I 2 = 33%, P = .54, 7 comparisons, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the mortality rates among residents following pharmacist intervention compared to usual care. The size of the data markers is determined by weight from random‐effects analysis, and the error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (CIs)

3.4.4. Hospital usage and admission

Five studies reported hospital usage and admission among their residents as an outcome.26, 37, 42, 52, 60 In the 3 studies that reported the number of residents who were hospitalised, pooled estimates suggest that pharmacist intervention in nursing home reduced hospital usage and admission (risk ratio: 0.57; 0.28–1.16; I 2 = 57%, P = .13, Figure S2).

3.4.5. Quality of prescribing—medication appropriateness

Four studies measured and reported the change in quality of prescribing after intervention by pharmacist, using the MAI tool.41, 52, 53, 54 Mean MAI score was found to improve by 2.2 (0.28–4.12; I 2 = 44%, P = .02), suggesting better medication management in the intervention group compared to control (Figure S3).

3.4.6. Quality of prescribing—medication usage by residents

Pharmacist‐led services was reported to consistently reduce the number of drugs taken per resident from a median of 7.2 (range 2.1–13.5) to 5.3 (range 2.1–12.0). In particular, the services significantly reduced the number of when necessary drugs, laxatives70 and anti‐inflammatories59 used by residents.

3.4.7. Cost analysis

Twenty‐five studies reported descriptive cost data, 21 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 50 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 63 , 67 , 69 , 70 , 71 with 22 studies reporting that intervention resulted in modest cost savings due to a reduction in medication bills (Table S5). However, none of the 25 studies conducted a comprehensive economic evaluation.

3.4.8. Adverse events

Three studies had reported the adverse events associated with their intervention.31, 52, 68 In all studies, there was no evidence that the introduction of a pharmacist could reduce the number of adverse drug events.

3.4.9. Physician acceptance of pharmacotherapy adjustments/recommendations by pharmacists

The overall acceptance rate by physicians on pharmacists' recommendation in nursing homes ranged from 31.4 to 100%, with a pooled acceptance rate of 69.8% (95% CI: 63.4%–76.2%; I 2 = 99.4%, Figure S4), but there was some evidence of publication bias. Stratification by study designs, year and type of service did not reduce the heterogeneity. Funnel plot constructed from the 24 studies included in the analysis showed that asymmetrical scatter (Figure S5).

3.4.10. Other outcomes

Several studies identified in the review had also reported clinical outcomes such as quality of life,35, 42, 49 activities of daily living,35, 49 mental health34 and depression.34 However, these studies reported no differences in these outcomes with the introduction of a pharmacist.

3.4.11. Certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence on treatment outcomes varied; it was moderate for the primary outcomes mortality and number of fallers. For other outcomes, these were rated low to very low (Table S5).

4. DISCUSSION

Medication safety among older adults living in nursing homes is critical, due to the vulnerability of this population. Our review found that most of the services provided by pharmacists aimed to address medication safety among residents, but there was considerable diversity on how these services were delivered, including clinical medication review, staff education, multidisciplinary team meetings, or a multifaceted intervention combining 2 or more interventions. Pooled analysis demonstrated that pharmacists' services were very successful in improving 1 of the most important outcomes in nursing homes, namely reducing the mean number of falls among residents. Similarly, the introduction of pharmacist service into nursing homes also reduced mortality rates, hospitalisation and admission rates, albeit not significantly.

Nevertheless, we note that while the pharmacist intervention had reduced the mean number of falls among residents, there was limited impact on the number of fallers. This could be due to the multifactorial nature of falls, as falls result from interactions between multiple individual and environmental risk factors, such as history of previous falls, demographics, functional limitations, health habits, and medications such as antidepressants, sedatives and antipsychotics.74, 75 In addition, the choice of outcome measures may also have impacted the results, since some residents in nursing homes may experience multiple falls during the study.

Medication reviews have often been proposed and introduced as a method to improve prescribing practice among older adults. While there are no universally accepted models for medication review, this usually involves a systematic assessment of a patient, with the aim of optimising drug treatment and quality of prescribing. The value of a pharmacist in conducting medication reviews has been well established to optimise pharmacotherapy and reduce inappropriate prescribing in hospitals, community pharmacies and outpatient clinics. Besides improving the quality of prescribing, medication review has positive impact on quality of life, reducing hospitalisation rates and reducing health care costs.7, 10 This review similarly noted that pharmacist services in nursing homes led to an improvement in the quality of prescribing, as evidenced by a reduction of the MAI scores by 2.2 points. While the introduction of a medication review service indicates a potential for improved prescribing practice, the clinical benefits of such services cannot be assumed. Many studies in this review had not measured the benefits and harms associated with pharmacists' services. Only few studies had reported outcomes such as fall rates, number of fallers, hospitalisation days and other outcomes such as quality of life. This underscores the need for better‐designed, long‐term studies that use clinical outcomes to assess the effects of having a pharmacist.

The process of deprescribing, which refers to the tapering, stopping, discontinuing or withdrawing of drugs, has received attention over the past few years as it has the potential to reduce the issue of polypharmacy and improving outcomes. This is also a process of simplification of the patient's medication regime.5, 76, 77 In this review, we found that the introduction of pharmacists into nursing homes had positively impacted to reduce the number of medicines taken by residents from a median of 7.2 drugs per resident to 5.3 drugs. This was similarly reported in a recent review by Kua and colleagues, which had reported that deprescribing led to improvements in multiple health outcomes, including reducing the number of potentially inappropriate medications, mortality rates and number of fallers.78 Taken together, findings of this review suggests that pharmacists could be incorporated as part of the professional team care in nursing homes.

Results of this study also concur with a previous review by Verrue and colleagues,13 which found that interventions by pharmacists in nursing homes generally reduced inappropriate prescribing and improved the knowledge of health care workers in nursing homes. Nevertheless, the review noted that there were methodological limitations in the studies identified, which we similarly noted in the current review. This suggests that there needs to be better designed randomised controlled studies evaluating outcomes that are needed in nursing homes. These studies should ideally focus on multidisciplinary collaboration and include elements of clinical medication review, education and academic detailing. The use of technology to reduce the risk of falls, such as videogame‐based exercise could also be considered, as it can help improve gait and balance, as well as physical performance among older adults.79, 80

Despite the available literature evaluating pharmacists' services in nursing homes, only a few studies evaluated the cost‐effectiveness of such service. Most of the published studies only provided a descriptive discussion of the decremental medication costs and associated cost savings, and none had conducted a formal economic evaluation. This could potentially be the challenges associated with economic evaluation in this setting, including lack of data on quality‐adjusted life years, due to the relative insensitivity of such a tool among these residents, and minimal improvement in life expectancy. Nevertheless, we believe that such evaluations are important to guide health authorities to plan and determine the value of such services as well as for future reimbursement strategies.

Results of this study need to consider the current study weaknesses. Firstly, we only included studies published in English and thus may have missed studies published in other languages. Most of the studies identified were cross‐sectional or retrospective studies with very few RCTs. As such, according to GRADE framework, the strength of evidences is considered weak to very weak in many outcomes and thus should be interpreted with caution. Finally, many of the included studies failed to use validated tools such as the START/STOPP or MAI. Nevertheless, we believe that information provided by the current review fills an important gap in the literature and thus is beneficial to support policy makers in formulating future professional services in this setting. Heterogeneity was notable among studies included in the analysis of physician acceptance rate (I 2 = 99%). Although this study had focused on intervention based in nursing homes, the selected interventions are still diverse, in particular in terms of intervention components (including intensity of service, frequency and total duration), study location and participants. While we attempted to explore the sources of heterogeneity using subgroup analyses based upon study design, study year as well as type of service provided by pharmacists, there remains inconsistency in definition which may partly explain the heterogeneity observed. Similarly, the definition of nursing homes and services provided to residents differs. For example, in the Netherlands nearly all patients living in nursing homes have limited life expectancies, and these patients are usually very frail due to e.g. dementia or multiple physical complaints and will be unlikely to return to their homes. These diversities in definitions and services provided may partly explain the heterogeneity observed in the review.

4.1. Implications for research and practice

Pharmacists contribute substantially to patient care and, in nursing homes, take on the roles of educators, leaders and researchers in ensuring the effective and safe use of medicine. In particular, they ensure that the prescribing is safe, effective and economical, and that both prescribers and home residents have the information they need to ensure that patients obtain the maximum benefits from their treatment. It is anticipated that the role of pharmacists, especially in low and middle income countries, will continue to expand in the future with the increasing number of older adults.81 While studies have shown that the introduction of a clinical pharmacist, medication reviews and deprescribing can reduce the drug burden, the evidence base to support these efforts are generally of low quality and focused in high income countries. Nevertheless, it is heartening to know that several sufficiently powered studies are currently underway to examine this important aspect of pharmacist services in nursing home especially in Asia.76, 82 Another aspect that needs further examination is the impact and potential financial costs of introducing such services to nursing homes, as well as better reporting of patient reported outcomes, such as falls, hospitalisation rates, resident's quality of life and activities of daily living.

5. CONCLUSION

This review noted mixed results on the impact of pharmacist services, but there was some promising evidence to suggest that these services to improve quality use of medication resulted in reduced mean number of falls in nursing homes. This could be due to the heterogeneity of medication review approach, its description as well as setting. As such, there is a need for better research and reporting of these studies measuring important patient reported outcomes such as falls and mortality.

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

V.S.L.M. and S.W.H.L. contributed to the study concept and design. Y.W.T. and S.W.H.L. contributed to the data collection, analyses, interpretation of data and preparation of draft. All authors contributed to the revision and final approval of manuscript.

Supporting information

TABLE S1

Search results of individual databases

TABLE S2 Quality of included case–control, pre–post and retrospective studies using the modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale

TABLE S3 Quality of included case–control studies using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale

Details of educational intervention provided by pharmacists in nursing homes

TABLE S5 Potential cost savings of pharmacist services to the nursing homes

TABLE S5 Details of GRADE classification

FIGURE S1 (A) Methodological quality assessment of included randomised controlled studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. (B) Methodological quality assessment of each domain of the included randomised controlled studies

FIGURE S2 Forest plot showing the odds of hospital usage and admission among residents following pharmacist intervention compared to usual care

FIGURE S3 Forest plot comparing the change in quality of prescribing between residents, assessed using the medication appropriateness index. The Medication Appropriateness Index comprises of 10 questions regarding a particular medication in order to determine its appropriateness for a patient. Higher scores indicate inappropriate prescribing

FIGURE S4 Forest plot showing the pooled physician acceptance rate of pharmacotherapy adjustments as recommended by pharmacists.

FIGURE S5 Funnel plot of studies included in analysis of physician acceptance rate

Lee SWH, Mak VSL, Tang YW. Pharmacist services in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2668–2688. 10.1111/bcp.14101

PI statement: The authors confirm that the Principal Investigator for this paper is Shaun Wen Huey Lee and that he had direct clinical responsibility for patients.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organisation . Ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cadogan CA, Ryan C, Hughes CM. Appropriate polypharmacy and medicine safety: when many is not too many. Drug Saf. 2016;39(2):109‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee SW, Chong CS, Chong DW. Identifying and addressing drug related problems in nursing homes: an unmet need in Malaysia? Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(6):512‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57‐65. 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee SWH, Mak VSL. Changing demographics in Asia: a case for enhanced pharmacy services to be provided to nursing homes. J Pharm Pract Res. 2016;46(2):152‐155. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang R, Chen L, Fan L, et al. Incidence and effects of polypharmacy on clinical outcome among patients aged 80+: a five‐year follow‐up study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hughes C, Winterstein A, McElnay J, et al. Improving the well‐being of elderly patients via community pharmacy‐based provision of pharmaceutical care: a multicentre study in seven European countries. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:63‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SWH, Ng KY, Chin WK. The impact of sleep amount and sleep quality on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;31:91‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fried TR, O'Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community‐dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2261‐2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castelino RL, Bajorek BV, Chen TF. Targeting suboptimal prescribing in the elderly: a review of the impact of pharmacy services. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1096‐1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):955‐964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teoh KW, Khan TM, Chaiyakunapruk N, Lee SWH. Examining the use of network meta‐analysis in pharmacy services research: a systematic review. J am Pharm Assoc. 2019. 10.1016/j.japh.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Verrue CL, Petrovic M, Mehuys E, Remon JP, Vander Stichele R. Pharmacists' interventions for optimization of medication use in nursing homes: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(1):37‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thiruchelvam K, Hasan SS, Wong PS, Kairuz T. Residential aged care medication review to improve the quality of medication use: a systematic review. J am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:87.e1‐87.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alldred DP, Kennedy MC, Hughes C, Chen TF, Miller P. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009095 10.1002/14651858.CD009095.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hatah E, Braund R, Tordoff J, Duffull SB. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of pharmacist‐led fee‐for‐services medication review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(1):102‐115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. Newcastle‐Ottawa quality assessment scale, cohort studies. 2014.

- 18. Ryan R, Hill S. How to GRADE the quality of the evidence. Cochrane consumers and communication group, available at http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Version 3.0. December 2016. In, 2016.

- 19. Cooper JW Jr, Bagwell CG. Contribution of the consultant pharmacist to rational drug usage in the long‐term care facility. J am Geriatr Soc. 1978;26(11):513‐520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller DA, Lucarotti RL, Vlasses PH, Krigstein DJ, McKercher PL. Perceived clinical significance of consultant pharmacist recommendations in the skilled nursing facility. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1980;14(3):182‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Strandberg LR, Dawson GW, Mathieson D, Rawlings J, Clark BG. Effect of comprehensive pharmaceutical services on drug use in long‐term care facilities. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1980;37(1):92‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young L, Leach D, Anderson D, Rice R. Decreased medication costs in a skilled nursing facility by clinical pharmacy services. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4(4):233‐237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garnett WR, Goldberg JA, Lowenthal W. Implementation and evaluation of clinical pharmacy services in an extended care facility. Gerontologist. 1981;21(2):151‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chrymko MM, Conrad WF. Effect of removinign clinical pharmacy input. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1982;39:641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Studnicki‐Gizbert D, Segal HJ. Effectiveness of selected pharmacy services in long term care facilities. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1983;1:187‐193. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thompson JF, McGhan WF, Ruffalo RL, Cohen DA, Adamcik B, Segal JL. Clinical pharmacists prescribing drug therapy in a geriatric setting: outcome of a trial. J am Geriatr Soc. 1984;32(2):154‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pink LA, Cooper JW, Francis WR. Digoxin‐related pharmacist‐physician communications in a long‐term facility: their acceptance and effects. Nurs Homes. 1985;34(1):25‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller SW, Marshall LL, Preston MW. Impact of pharmacist‐conducted drug‐regimen review on drug use in an intermediate‐care facility. Consult Pharm. 1991;5:317‐322. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laucka PV, Hoffman NB. Decreasing medication use in a nursing‐home patient‐care unit. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49(1):96‐99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rees JK, Livingstone DJ, Livingstone CR, Clarke CD. Community clinical pharmacy service for elderly people in residential homes. Pharm J. 1995;255:54‐56. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bellingan M, Wiseman IC. Pharmacist intervention in an elderly care facility. Int J Pharm Pract. 1996;4(1):25‐29. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deshmukh AA, Sommerville H. A pharmaceutical advisory service in a private nursing home: provision and outcome. Int J Pharm Pract. 1996;4(2):88‐93. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elliott RA, Thomson WA. Assessment of a nursing home medication review service provided by hospital‐based clinical pharmacists. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 1999;29(5):255‐260. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Furniss L, Burns A, Craig SKL, Scobie S, Cooke J, Faragher B. Effects of a pharmacist's medication review in nursing homes. Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176(6):563‐567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ulfvarson J, Adami J, Ullman B, Wredling R, Reilly M, von Bahr C. Randomized controlled intervention in cardiovascular drug treatment in nursing homes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12(7):589‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trygstad TK, Christensen D, Garmise J, Sullivan R, Wegner SE. Pharmacist response to alerts generated from Medicaid pharmacy claims in a long‐term care setting: results from the North Carolina polypharmacy initiative. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(7):575‐583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, et al. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care homes‐‐randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2006;35(6):586‐591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bruce R. Pharmacy input in medications review improves prescribing and cost‐efficiency in care homes. Pharmacy in Practice. 2007;17:243‐246. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishtala PS, Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Hannan PJ, Chen TF. Impact of residential medication management reviews on drug burden index in aged‐care homes: a retrospective analysis. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(8):677‐686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gugkaeva Z, Franson M. Pharmacist‐led model of antibiotic stewardship in a long‐term care facility. Ann Long‐Term Care. 2012;20:22‐26. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verrue C, Mehuys E, Boussery K, Adriaens E, Remon JP, Petrovic M. A pharmacist‐conducted medication review in nursing home residents: impact on the appropriateness of prescribing. Acta Clin Belg. 2012;67:423‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frankenthal D, Lerman Y, Kalendaryev E, Lerman Y. Intervention with the screening tool of older persons potentially inappropriate prescriptions/screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment criteria in elderly residents of a chronic geriatric facility: a randomized clinical trial. J am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(9):1658‐1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gheewala PA, Peterson GM, Curtain CM, Nishtala PS, Hannan PJ, Castelino RL. Impact of the pharmacist medication review services on drug‐related problems and potentially inappropriate prescribing of Renally cleared medications in residents of aged care facilities. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(11):825‐835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McLarin PE, Peterson GM, Curtain CM, Nishtala PS, Hannan PJ, Castelino RL. Impact of residential medication management reviews on anticholinergic burden in aged care residents. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(1):123‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chia HS, Ho JAH, Lim BD. Pharmacist review and its impact on Singapore nursing homes. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nishtala P, Castelino R, Peterson G, Hannan P, Salahudeen M. Residential medication management reviews of antithrombotic therapy in aged care residents with atrial fibrillation: assessment of stroke and bleeding risk. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(3):279‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gemelli MG, Yockel K, Hohmeier KC. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists on reducing use of sedative/hypnotics for treatment of insomnia in long‐term care facility residents. Consult Pharm. 2016;31(11):650‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee C, Lo A, Ubhi K, Milewski M. Outcome after discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors at a residential care site: quality improvement project. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017;70:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Midlov P, Bondesson A, Eriksson T, Petersson J, Minthon L, Hoglund P. Descriptive study and pharmacotherapeutic intervention in patients with epilepsy or Parkinson's disease at nursing homes in southern Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;57(12):903‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Christensen D, Trygstad T, Sullivan R, Garmise J, Wegner SE. A pharmacy management intervention for optimizing drug therapy for nursing home patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2(4):248‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lapane KL, Hughes CM. Pharmacotherapy interventions undertaken by pharmacists in the Fleetwood phase III study: the role of process control. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(9):1522‐1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, Giles LC, Phillips PA. Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence‐based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long‐term care facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2(4):257‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stuijt CC, Franssen EJ, Egberts AC, Hudson SA. Appropriateness of prescribing among elderly patients in a Dutch residential home: observational study of outcomes after a pharmacist‐led medication review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(11):947‐954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, et al. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004a;33(6):612‐617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miller SW, Marshall LL, Preston MW. Impact of pharmacist‐conducted drug‐regimen review on drug use in an intermediate‐care facility. Consult Pharm. 1991;6:317‐322. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Avorn J, Soumerai SB, Everitt DE, et al. A randomized trial of a program to reduce the use of psychoactive drugs in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(3):168‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chia HS, Ho J, Lim BDL. Pharmacist reviews and outcomes in nursing homes in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2013;59:493‐501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Patterson SM, Hughes CM, Cardwell C, Lapane KL, Murray AM, Crealey GE. A cluster randomized controlled trial of an adapted U.S. model of Pharmaceutical Care for Nursing Home Residents in Northern Ireland (Fleetwood Northern Ireland study): a cost‐effectiveness analysis. J am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):586‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wilcher DE, Cooper JW Jr. The consultant pharmacist and analgesic/anti‐inflammatory drug usage in a geriatric long‐term facility. J am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29(9):429‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cooper JW. Effect of initiation, termination, and reinitiation of consultant clinical pharmacist services in a geriatric long‐term care facility. Med Care. 1985;23(1):84‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schmidt IK, Claesson CB, Westerholm B, Nilsson LG. Physician and staff assessments of drug interventions and outcomes in Swedish nursing homes. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32(1):27‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eide E, Schjott J. Assessing the effects of an intervention by a pharmacist on prescribing and administration of hypnotics in nursing homes. Pharm World Sci. 2001;23(6):227‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. King MA, Roberts MS. Multidisciplinary case conference reviews: improving outcomes for nursing home residents, carers and health professionals. Pharm World Sci. 2001;23(2):41‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Finkers F, Maring JG, Boersma F, Taxis K. A study of medication reviews to identify drug‐related problems of polypharmacy patients in the Dutch nursing home setting. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(5):469‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Halvorsen KH, Ruths S, Granas AG, Viktil KK. Multidisciplinary intervention to identify and resolve drug‐related problems in Norwegian nursing homes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28(2):82‐88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Patterson SM, Hughes CM, Crealey G, Cardwell C, Lapane KL. An evaluation of an adapted US model of pharmaceutical care to improve psychoactive prescribing for nursing home residents in Northern Ireland (Fleetwood Northern Ireland study). J am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(1):44‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Brulhart MI, Wermeille JP. Multidisciplinary medication review: evaluation of a pharmaceutical care model for nursing homes. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;33(3):549‐557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Davidsson M, Vibe OE, Ruths S, Blix HS. A multidisciplinary approach to improve drug therapy in nursing homes. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:9‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Baqir W, Barrett S, Desai N, Copeland R, Hughes J. A clinico‐ethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes. BMJ Open Qual. 2014;3:u203261‐w2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Elzarian EJ, Shirachi DY, Jones JK. Educational approaches promoting optimal laxative use in long‐term‐care patients. J Chronic Dis. 1980;33(10):613‐626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roberts MS, Stokes JA, King MA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(3):257‐265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lau WM, Chan K, Yung TH, Lee AS. Outreach pharmacy service in old age homes: a Hong Kong experience. J Chin Med Assoc. 2003;66(6):346‐354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Crotty M, Whitehead C, Rowett D, et al. An outreach intervention to implement evidence based practice in residential care: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN67855475]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004b;4(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vieira ER, Palmer RC, Chaves PHM. Prevention of falls in older people living in the community. BMJ. 2016;353:i1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Liew NY, Chong YY, Yeow SH, Kua KP, San Saw P, Lee SWH. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications among geriatric residents in nursing care homes in Malaysia: a cross‐sectional study. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;41(4):895‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kua C‐H, Yeo CYY, Char CWT, et al. Nursing home team‐care deprescribing study: a stepped‐wedge randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827‐834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kua C‐H, Mak VSL, Huey Lee SW. Health outcomes of Deprescribing interventions among older residents in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;35(4):1061‐1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bateni H. Changes in balance in older adults based on use of physical therapy vs the Wii fit gaming system: a preliminary study. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(3):211‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tay EL, Lee SWH, Yong GH, Wong CP. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the efficacy of custom game based virtual rehabilitation in improving physical functioning of patients with acquired brain injury. Technol Disabil. 2018;30(1‐2):1‐23. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lee SWH, Bell JS. Pharmaceutical care in Asia In: The Pharmacist Guide to Implementing Pharmaceutical Care. New York, NY: Springer; 2019:191‐197. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sluggett JK, Chen EY, Ilomäki J, et al. SImplification of medications prescribed to long‐tErm care residents (SIMPLER): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TABLE S1

Search results of individual databases

TABLE S2 Quality of included case–control, pre–post and retrospective studies using the modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale

TABLE S3 Quality of included case–control studies using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale

Details of educational intervention provided by pharmacists in nursing homes

TABLE S5 Potential cost savings of pharmacist services to the nursing homes

TABLE S5 Details of GRADE classification

FIGURE S1 (A) Methodological quality assessment of included randomised controlled studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. (B) Methodological quality assessment of each domain of the included randomised controlled studies

FIGURE S2 Forest plot showing the odds of hospital usage and admission among residents following pharmacist intervention compared to usual care

FIGURE S3 Forest plot comparing the change in quality of prescribing between residents, assessed using the medication appropriateness index. The Medication Appropriateness Index comprises of 10 questions regarding a particular medication in order to determine its appropriateness for a patient. Higher scores indicate inappropriate prescribing

FIGURE S4 Forest plot showing the pooled physician acceptance rate of pharmacotherapy adjustments as recommended by pharmacists.

FIGURE S5 Funnel plot of studies included in analysis of physician acceptance rate