Abstract

Objective

We aimed to provide the first national estimates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training and awareness of cardiac arrest.

Design

A retrospective analysis of a national cross-sectional survey was undertaken. Data were collected online from adults in July 2017 as part of the Heart Foundation of Australia’s HeartWatch survey. We used logistic regression to examine demographic factors associated with CPR training.

Participants

A national cohort was invited to participate in the survey using purposive, non-probability sampling methods with quotas for age, gender and area of residence, in order to reflect the wider Australian population. The final sample consisted of 1076 respondents.

Main outcome measure

To determine an estimation of the prevalence of cardiac arrest awareness and CPR training at a national level and the relationship of training to demographic factors.

Results

The majority (76%) of respondents were born in Australia with 51% female and 66% aged between 35 and 64 years. Only 16% of respondents could identify the difference between a cardiac arrest and a heart attack. While 56% reported previous CPR training, only 22% were currently trained (within 1 year). CPR training was associated with younger age (35 to 54 years) (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.0), being born in Australia (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.17) and higher levels of education (university, OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.35 to 2.57). CPR training increased confidence in respondents ability to perform effective CPR and use a defibrillator. Lack of CPR training was the most common reason why respondents would not provide CPR to a stranger.

Conclusions

There is a need to improve the community’s understanding of cardiac arrest, and to increase awareness and training in CPR. CPR training rates have not changed over the past decades—new initiatives are needed.

Keywords: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, resuscitation, education & training (see medical education & training), public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first time a national perspective investigating the awareness of cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training has been undertaken in Australia.

A representative group of Australians were surveyed using probability sampling methods that included quotas for age, gender and area of residence.

While the limitations of cross-sectional survey methods include recall bias, our results are consistent with past surveys conducted in Australia.

Future surveys of this nature require validation of survey questions and could employ mixed methods of using both online and phone surveys to address the challenge of participants using online searches to source survey answers.

Introduction

Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) more than doubles the chance of surviving a cardiac arrest,1 2 however the provision of bystander CPR remains low.3 While there has been improvement in bystander CPR rates with the introduction of dispatcher-assisted CPR instructions during the emergency call,4 a significant proportion still do not feel confident to provide CPR even with instructions.5

There is growing evidence of a link between rates of bystander CPR and CPR training. Three studies have now reported communities with higher rates of bystander CPR have high rates of CPR trained residents.6–8 This most likely occurs because CPR training is significantly associated with increased confidence and willingness to provide CPR.9 10 Existing data also suggests specific demographics are associated with CPR training, including age, education level, country of birth and occupation.9–11 There is also a need to examine the impact of socioeconomic factors on rates of bystander CPR training, as regions with lower bystander CPR also have lower CPR training rates.12 13 Therefore, understanding current rates of CPR training in the community is important, and may drive local initiatives.

In Australia, CPR training is currently not mandatory, and state-based surveys9 14–16 suggest that less than 60% of Australian adults have received CPR training at least once. However, these surveys were conducted in specific regions, and most more than a decade ago. This study aimed to provide the first Australian-wide estimates of CPR training and willingness to learn CPR.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from the Heart Foundation of Australia’s ‘HeartWatch’ Survey. This quarterly survey is conducted using a purposive, non-probability sampling method with quotas for age, gender and area of residence, in order to reflect the characteristics of the wider Australian population. Respondents of the survey belong to an online survey panel. In July 2017, 21 questions about CPR were added to the survey, generated from previous Australian surveys.9 14–16 The CPR questions (online supplementary file 1) were in three sections: cardiac arrest knowledge, CPR knowledge and experience, and defibrillator knowledge.

bmjopen-2019-033722supp001.pdf (95.5KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The public were not invited to comment on the design of this study and were not consulted to develop relevant outcomes or interpret the results. The research group (Australian and New Zealand Prehospital Emergency Care Centre of Research Excellence) do however have representatives from the pubic on the steering committee who will be consulted about the outcomes and directions of dissemination of this research during regularly scheduled meetings. Results will also be disseminated via Heart Foundation of Australia channels in addition to the research group.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics with proportions expressed as percentages and tests of association using X2 statistic between respondent characteristics and CPR training status. Logistic regression was used to identify respondent characteristics independently associated with CPR training. Characteristics with p values <0.2 at the univariate level were included in the model. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis in a subsample of respondents excluding those who reported they had previously performed CPR. Free text responses were categorically coded by two healthcare professionals (Registered Nurse (SC) and Paramedic (DS)) in parallel, both of whom are experienced community first aid trainers. These authors met several times to compare and discuss coding frameworks with outstanding disagreements referred to a third author (JB). Statistical significance for quantitative analysis was set at p <0.05 and analysis was conducted with Stata V.15.1.

Results

The survey sample consisted of 1076 Australian adults. Responses were received from every state and territory in Australia (table 1). There was a similar proportion of female (n=554, 50.6%) and male (n=532, 49.4%) respondents. The majority were aged between 35 and 64 years (n=713, 66%), had completed at least 10 years of schooling (n=968, 90%) and were born in Australia (n=817, 76%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample according to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training status

| Overall n=1076 | ||||

| CPR trained n=540 (55.7%) |

Not CPR trained n=429 (44.3%) |

P value | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 544 (50.6%) | 292 (54.1%) | 210 (48.9%) | 0.11 |

| Male | 532 (49.4%) | 248 (45.9%) | 219 (51.1%) | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 334 (31.0%) | 154 (28.5%) | 135 (31.4%) | 0.07 |

| 35–54 | 430 (40.0%) | 231 (42.8%) | 149 (34.7%) | |

| 55-74 | 283 (26.3%) | 142 (26.3%) | 130 (30.3%) | |

| 75+ | 29 (2.7%) | 13 (2.4%) | 15 (3.5%) | |

| Country of birth | ||||

| Australia | 817 (75.9%) | 431 (79.8%) | 311 (72.5%) | 0.03 |

| Overseas | 253 (23.5%) | 108 (20.0%) | 116 (27.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (0.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| State | ||||

| Australian Capital Territory | 8 (0.7%) | 4 (0.7%) | 4 (0.9%) | 0.83 |

| New South Wales | 339 (31.5%) | 174 (32.2%) | 127 (29.6%) | |

| Northern Territory | 4 (0.4%) | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Queensland | 218 (20.3%) | 111 (20.6%) | 92 (21.4%) | |

| South Australia | 85 (7.9%) | 43 (8.0%) | 33 (7.7%) | |

| Tasmania | 24 (2.2%) | 16 (3.0%) | 6 (1.4%) | |

| Victoria | 284 (26.4%) | 132 (24.4%) | 115 (26.8%) | |

| Western Australia | 114 (10.6%) | 58 (10.7%) | 44 (10.3%) | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary or grade school | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | <0.001 |

| Some high school | 97 (9%) | 41 (7.8%) | 44 (10.3%) | |

| High school graduate | 193 (17.9%) | 75 (13.9%) | 104 (24.2%) | |

| Technical college | 302 (28.1%) | 179 (33.2%) | 102 (23.8%) | |

| University diploma | 332 (30.9%) | 161 (29.8%) | 133 (31.0%) | |

| Postgraduate | 141 (13.1%) | 78 (14.4%) | 43 (10.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (0.8%) | 5 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Previously performed emergency CPR | 95 (8.8%) | 84 (15.5%) | 11 (2.6%) | <0.0001 |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Cardiac arrest knowledge

Respondents were asked if they ‘knew the difference between a cardiac arrest and a heart attack’. The majority of respondents stated they were ‘unsure’ (n=404, 37.6%), followed by ‘yes’ (n=356, 33.1%), with the remaining responding ‘no’ (n=316, 29.4%). The majority of those responding ‘yes’ had received CPR training (72%). Those who answered ‘yes’ were then asked to describe the difference between the two conditions using free text. Less than half of the ‘yes’ respondents identified the two conditions correctly (n=174, 48.3%), however 22.2% (n=79) identified the conditions incorrectly or only had definitions partially correct (n=66, 18.5%). A small proportion (n=37, 10.4%) of yes respondents declared they were unsure when asked for a definition. When coding free text descriptions it was noted that several respondents (n=10, 2.8%) had used the exact same wording. This wording was identical to the top result from online search engine Google when searching the question verbatim.

Knowledge of signs of cardiac arrest were variable among respondents. When coding free text responses according to Australian Resuscitation Council criteria (unresponsive and not breathing normally),17 only 2.9% (n=32) of respondents answered correctly. However, many respondents described the absence of a pulse (‘no heart beat’, ‘heart stops’), which has been removed within the last decade as a criteria for cardiac arrest in accredited Australian CPR training and from emergency call dispatch CPR instructions.4 When we added the absence of a pulse as a correct descriptor of cardiac arrest, 14.2% (n=153) of respondents had the answer coded as correct. Commonly respondents described a cardiac arrest victim as either unconscious or having an absence of breathing (n=97, 9%). Incorrect answers (n=684, 63.6%) featured chest pain, shortness of breath, weakness and dizziness. Numerous respondents (n=127, 11.8%) stated they were unsure of the signs and symptoms.

CPR knowledge, confidence and training preferences

The majority of respondents (n=969, 90.1%) had heard of CPR. Few respondents (n=95, 8.8%) had previously performed CPR. When respondents were asked what they would do if someone was in cardiac arrest, only nine (0.8%) respondents correctly identified the chain of survival18 sequence of calling an ambulance, commencing CPR and applying a defibrillator. These respondents all had prior CPR training within 5 years. More respondents (n=141, 13%) were able to identify two correct actions (ie, calling an ambulance, and CPR or defibrillation). A smaller proportion (n=121, 11.2%) described CPR and or defibrillation but did not mention calling an ambulance. The majority of respondents (n=536, 49.7%) responded they would call an ambulance, but did not describe any further actions.

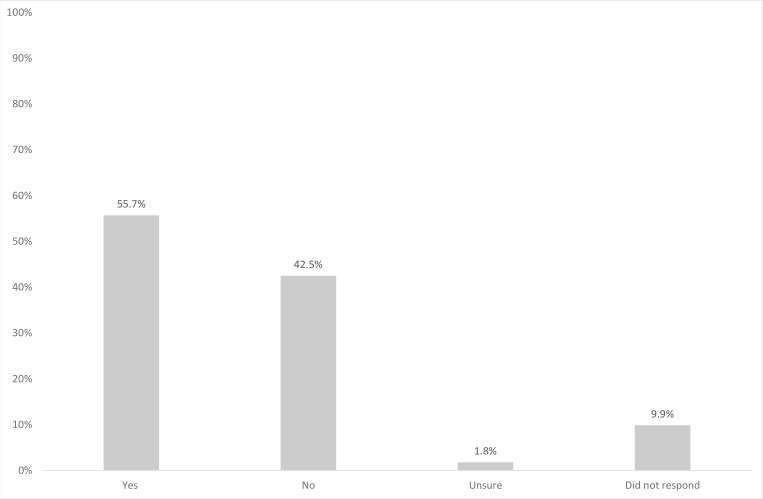

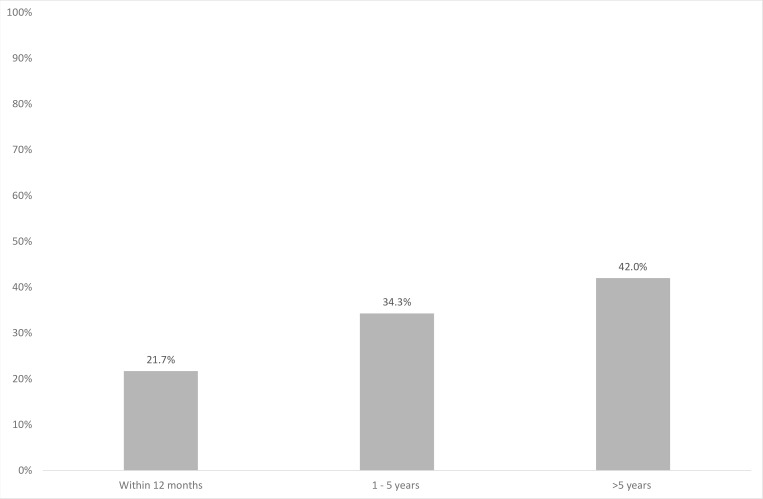

In total 55.7% (n=540) of respondents had undertaken CPR training previously, however a large proportion (42.5%, n=412) had not, and a small proportion were unsure (n=17, 1.8%,) or did not answer (n=107, 9.9%) (figure 1). The majority of CPR trained respondents had not been trained in CPR for over 5 years (n=227, 42%), with only 21.7% (n=117) classified as being currently trained (within 12 months) as per Australian guidelines19 (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Proportion (%) of sample who have ‘ever had’ cardiopulmonary resuscitation training.

Figure 2.

Of those with cardiopulmonary resuscitation training, years (proportion, %) since last training completed.

CPR training was not associated with any region (state or territory) of residence (table 2) or socioeconomic status (all deciles p >0.05, data not shown). However, CPR training was associated with age 35 to 54 years (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.00), Australian-born (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.17) and university (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.35 to 2.57) and vocational level of education (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.64 to 3.30) (table 2). These factors remained significant when restricted to those who had not previously performed CPR. The main barriers to learning CPR included lack of awareness (‘never thought about it’) (n=190, 44.3%), not knowing where to go to learn (n=91, 21.2%) and cost (n=52, 12.1%).

Table 2.

Factors associated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation training

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Females | 1.30 (0.99 to 1.70) | 0.05 |

| Age | ||

| 18–34 | Ref | |

| 35–54 | 1.45 (1.06 to 2.00) | 0.02 |

| 55–74 | 1.11 (0.78 to 1.58) | 0.55 |

| >75 | 0.92 (0.42 to 2.06) | 0.85 |

| Australian born | 1.59 (1.17 to 2.17) | 0.003 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | Ref | |

| Vocational college | 2.33 (1.64 to 3.30) | <0.001 |

| University | 1.86 (1.35 to 2.57) | <0.001 |

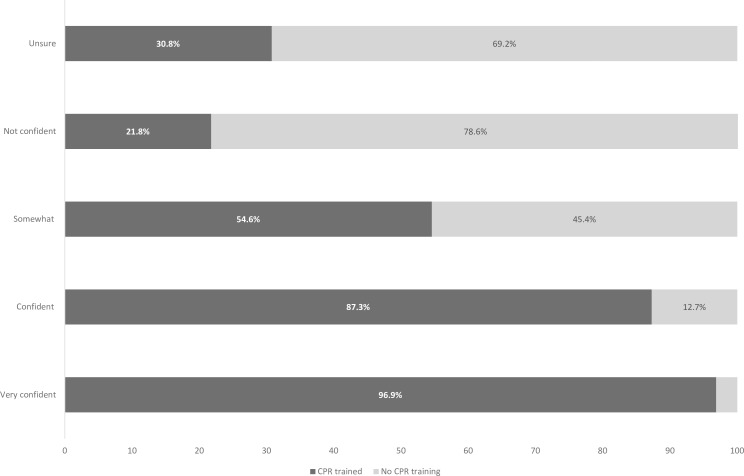

The relationship between confidence in ability to provide CPR was significantly related to CPR training status, with respondents who stated they were very confident to perform CPR more likely to have CPR training (p <0.001) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Self-rated confidence levels (%) of ability to perform effective cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in an emergency according to CPR training status.

Of those with no prior CPR training, the majority (n=312, 72.7%) of respondents were willing to learn CPR with only small proportion of respondents stating they were unsure (n=74, 17.2%) or unwilling (n=26, 6.1%). The preferred format for CPR training was for group learning, led by a professional provider (n=237, 76%) with a smaller proportion choosing learning via self-instruction (n=57, 18.3%).

Barriers to performing CPR

Only half (n=530, 49.3%) of respondents stated they would provide CPR to a stranger. The remaining respondents were predominantly unsure (n=307, 28.5%). In those that responded no (n=132, 12.3%) the most common response was not being trained in CPR (n=57, 43.2%) or not feeling confident (n=26, 19.7%). Fear (n=9, 6.8%), a physical inability (n=5, 3.8%) or concern over legalities (n=5, 3.9%) were other factors mentioned, with only two (1.5%) mentioning fear of infection.

Defibrillator knowledge,confidence and willingness

The majority of respondents (n=903, 83.9%) had heard of a defibrillator and of these respondents more than half (n=633, 58.8%) would be willing to use it. However confidence levels to use a defibrillator were low, with a fifth (n=215, 20.0%) stating they were not confident (online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2019-033722supp002.pdf (99.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

In this national study, just over half (56%) of Australian adults reported ever having undertaken CPR training, however only 22% had current (within 1 year) training. CPR training was associated with younger age (35 to 54 years), being born in Australia and having a higher level of education. The association between these demographics and CPR training are similar to studies conducted in other countries.9–11 Alarmingly however, this study found a low understanding of cardiac arrest, or being able to identify the actions involved with the chain of survival. There is a large opportunity to increase national training prevalence, as the majority of those who were untrained in CPR are willing to learn and identified that learning in a group class, led by a professional instructor was the preferred learning format.

The prevalence of CPR training in this Australian study (56%) is similar to other recent international surveys conducted in the UK (57%)10 and the USA (65%).11 Unlike these countries however, Australia has no national or state-based mandatory training strategy, and there has only been limited attempts to promote awareness of cardiac arrest and CPR via mass-media (eg, Shock Verdict https://www.utas.edu.au/shockverdict). These strategies are important to increase cardiac arrest and CPR training knowledge and awareness and should be considered.

In Australia, CPR training is only mandatory for selected professions (ie, healthcare professionals, teachers, childcare workers and fitness instructors).20 The effect of workplace training is likely evidenced in our results by the fact younger working ages (35 to 54 years, OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.00) and those who attended both vocational college (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.64 to 3.30) and university (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.35 to 2.57) were independently associated with CPR training. Recent evidence from the USA21 demonstrates that mandatory CPR training in schools is associated with higher levels of individuals who are currently trained in CPR. Mandatory community-level training strategies require cooperation from many parties including federal and state governments and Resuscitation Councils. Nevertheless, these strategies have been successfully implemented elsewhere and they should not be overlooked, as they could ensure a large proportion of the community receive CPR training, at least once in their lifetime.

Our results, as has been identified before,10 22 23 also demonstrate that those with CPR training had higher levels of self-reported confidence to perform CPR and use a defibrillator. Concurrently, the most common barrier to not performing CPR in this study was lack of training. This highlights the importance of CPR training, especially given the positive link between levels of training and bystander CPR rates.6–8 CPR training is consistently related to younger age and higher levels of education both in Australia9 14 and internationally.11 Future training initiatives need to consider targeting populations less likely to receive training, particularly those that are older, who are at higher risk of future cardiac events. Along with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation,24 we also place value on training high-risk populations, such as households containing a person with heart disease and have success in piloting a targeted training programme through cardiac rehabilitation programmes.25

In addition to training, raising awareness of cardiac arrest and CPR training is essential. A significant proportion of respondents in our study had never thought about CPR training or didn’t know where to go to receive training. A national and coordinated campaign to increase public awareness of cardiac arrest and CPR training is warranted given the low rates of knowledge assessed in this study. Highlighting the simplification of CPR through promoting the ‘hands-only’ CPR technique may encourage more people to render assistance in an emergency and to undertake training. As traditional television, radio and print mass media campaigns are very costly, dissemination of these messages via social media should be investigated.26 These approaches could be successful as smartphones and other digital mobile devices are almost ubiquitous in Australia, including among older Australians.27

In the modern era, CPR training can be provided in many formats (eg, with an instructor, via self-instruction, online). The majority of respondents in our study stated they would prefer to learn from an instructor in a class, with a smaller proportion preferring self-instruction. Now that ‘hands-only’ CPR is the preferred teaching method for lay people,17 the simplified algorithm has the benefits of being appropriate for all levels of literacy and education, in addition to decreasing barriers to performing CPR (such as mouth-to-mouth ventilations).9 28

Our study is subject to a number of potential limitations. First, the online survey may be subject to selection bias and the results may only be applicable to those who respond to online surveys. However, the rationale of the sampling method used was to generate a sample which matched the characteristics (ie, age, sex, nationality) of the underlying Australian population. Second, the survey questions were not formally validated. It is therefore possible that some respondents may not have understood some of the questions or terms such as cardiac arrest. We also acknowledge that survey methodology is subject to recall bias. However, our results are consistent with previous Australian14 15 and international research.10 11 Third, the survey was restricted to those who could read and respond in English. Additionally, future online surveys need to be aware that some participants will undertake an online search to source answers. In our case, we saw 10 identical answers to one question and on further examination determined these had been copied and pasted from the top search result of Google. Future online surveys could supplement responses using other methods such as restricting online access during data collection or conducting a telephone survey to address this issue.

Conclusion

Our data suggest CPR training rates in Australia are unchanged over the past decades, however the majority of untrained respondents were willing to learn. This willingness should be leveraged through national training and awareness strategies to increase knowledge of cardiac arrest and CPR. Such strategies need to consider targeting training to men, those with lower levels of education and those born overseas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Australian and New Zealand Prehospital and Emergency Care Centre of Research Excellence (No. 1116453)

Footnotes

Twitter: @susiecartledge

Presented at: Spark of Life Conference, Australian Resuscitation Council, May 2019

Contributors: SC and JB led the data analysis and drafted the paper. DS contributed to data analysis. All authors (SC, JB, DS and JF) contributed to critical revisions of the paper.

Funding: Associate Professor Bray was funded by a Heart Foundation Fellowship (No. 101171). The study was also supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funded Australian and New Zealand Prehospital Emergency Care (PEC-ANZ) Centre of Research Excellence (No. 1116453).

Competing interests: JF and JB hold appointments with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). JF holds an Adjunct Research Professor appointment with St John Western Australia.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The present study was granted an ethics exemption from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Number: 12329) as data provided for the research by the Heart Foundation of Australia was de-identified.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Sasson C, Rogers MAM, Dahl J, et al. . Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:63–81. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.889576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hasselqvist-Ax I, Riva G, Herlitz J, et al. . Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2307–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa1405796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beck B, Bray J, Cameron P, et al. . Regional variation in the characteristics, incidence and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Australia and New Zealand: results from the Aus-ROC Epistry. Resuscitation 2018;126:49–57. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bray JE, Deasy C, Walsh J, et al. . Changing EMS dispatcher CPR Instructions to 400 compressions before mouth-to-mouth improved bystander CPR rates. Resuscitation 2011;82:1393–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Case R, Cartledge S, Siedenburg J, et al. . Identifying barriers to the provision of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in high-risk regions: a qualitative review of emergency calls. Resuscitation 2018;129:43–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bray JE, Straney L, Smith K, et al. . Regions with low rates of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) have lower rates of CPR training in Victoria, Australia. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005972 10.1161/JAHA.117.005972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, YS R, Do Shin S, et al. . Public awareness and self-efficacy of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in communities and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a multi-level analysis. Resuscitation 2016;102:17–24. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson ML, Cox M, Al-Khatib SM, et al. . Rates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:194 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bray JE, Smith K, Case R, et al. . Public cardiopulmonary resuscitation training rates and awareness of hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a cross-sectional survey of Victorians. Emerg Med Australas 2017;29:158–64. 10.1111/1742-6723.12720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawkes CA, Brown TP, Booth S, et al. . Attitudes to Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Defibrillator Use: A Survey of UK Adults in 2017. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e008267 10.1161/JAHA.117.008267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blewer AL, Ibrahim SA, Leary M, et al. . Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training disparities in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e006124 10.1161/JAHA.117.006124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sasson C, Magid DJ, Chan P, et al. . Association of neighborhood characteristics with bystander-initiated CPR. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1607–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaillancourt C, Lui A, De Maio VJ, et al. . Socioeconomic status influences bystander CPR and survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims. Resuscitation 2008;79:417–23. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith KL, Cameron PA, Meyer ADM, et al. . Is the public equipped to act in out of hospital cardiac emergencies? Emerg Med J 2003;20:85–7. 10.1136/emj.20.1.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jelinek GA, Gennat H, Celenza T, et al. . Community attitudes towards performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Western Australia. Resuscitation 2001;51:239–46. 10.1016/S0300-9572(01)00411-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnston TC, Clark MJ, Dingle GA, et al. . Factors influencing Queenslanders' willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2003;56:67–75. 10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00277-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation ANZCOR guideline 8, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 2016. Available: https://resus.org.au/guidelines/ [Accessed 14 Nov 2016].

- 18. Cummins RO, Ornato JP, Thies WH, et al. . Improving survival from sudden cardiac arrest: the "chain of survival" concept. A statement for health professionals from the Advanced Cardiac Life Support Subcommittee and the Emergency Cardiac Care Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation 1991;83:1832–47. 10.1161/01.CIR.83.5.1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation ANZCOR guideline 10.1, basic life support training, 2016. Available: https://resus.org.au/guidelines/ [Accessed 14 Nov 2016].

- 20. Safe Work Australia Safe work Australia first aid. Available: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/first-aid [Accessed 29 Jun 2019].

- 21. Alexander TD, McGovern SK, Leary M, et al. . Association of state-level CPR training initiatives with layperson CPR knowledge in the United States. Resuscitation 2019;140:9–15. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gräsner J-T, Lefering R, Koster RW, et al. . EuReCa ONE-27 nations, one Europe, one registry: a prospective one month analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in 27 countries in Europe. Resuscitation 2016;105:188–95. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perkins GD, Travers AH, Berg RA, et al. . Part 3: adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation: 2015 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation 2015;95:e43–69. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Finn JC, Bhanji F, Lockey A, et al. . Part 8: education, implementation, and teams: 2015 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation 2015;95:e203–24. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cartledge S, Finn J, Bray JE, et al. . Incorporating cardiopulmonary resuscitation training into a cardiac rehabilitation programme: a feasibility study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018;17:148–58. 10.1177/1474515117721010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greif R, Lockey AS, Conaghan P, et al. . European resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 10. education and implementation of resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015;95:288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deloitte Mobile phone consumer survey 2015 - The Australian Cut, 2017. Available: http://landing.deloitte.com.au/rs/761-IBL-328/images/tmt-mobile-consumer-survey-2017_pdf.pdf [Accessed 30 Apr 2019].

- 28. Sasson C, Haukoos JS, Bond C, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to learning and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in neighborhoods with low bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation prevalence and high rates of cardiac arrest in Columbus, OH. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:550–8. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033722supp001.pdf (95.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033722supp002.pdf (99.7KB, pdf)